Chess

Notes

Edward

Winter

When contacting

us

by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include

their name and full

postal address and, when providing

information, to quote exact book and magazine

sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the

subject-line or in the message itself.

6701. Early Reshevsky photograph

This particularly early photograph of Reshevsky, from

page 11 of Wiener Bilder, 30 September 1917, has

been submitted by Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech

Republic):

Mr Kalendovský also draws attention to a photograph

of Petrosian (signed by the master overleaf) in his

collection:

From Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England):

‘C.N. 6678 mentioned that the Alain White

Collection was housed in the South Africa National

Library. However, this is a collection not of A.C.

White’s own chess books but of about 500 volumes

compiled by Donald G. McIntyre and named after

A.C. White.

That information comes from the

Special

Collections section of the National Library of

South Africa website.’

Our correspondent asks what became of A.C. White’s own

chess book collection, which numbered ‘somewhat less

than 2,000 volumes’ in 1907, according to an article by

White on page 38 of the Chess Amateur, November

1907.

Wanted: substantiation of this ‘once’ quotation:

‘Alekhine once said, “There must be no reasoning

from past moves, only from the present position”.’

Source: The Golden Dozen by Irving Chernev

(Oxford, 1976), page 260.

Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) writes:

‘My copy of Stamma’s The Noble Game of

Chess (London, 1745), which introduced the

algebraic notation to the West, has the bookplate

of the “Marquis Townshend”. I found that the first

Marquis was the brother of the man who authored

the “Townshend Acts”, which were among the sparks

that helped bring on the American Revolution. The

Marquis title was first conferred on the family

some years after 1745.

I wonder whether my copy belonged to that first

Marquis. His son, who inherited the title, was an

avid book collector.’

Among the subscribers to Philidor’s Analyse du

jeu des échecs was ‘M. Townshend’.

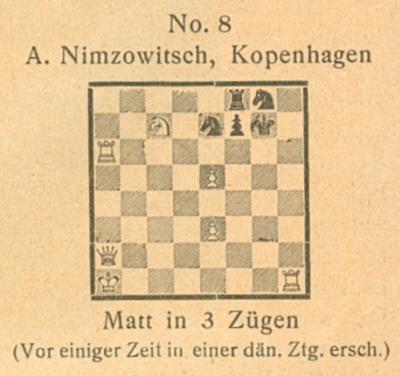

6706. A mate in three by Nimzowitsch

(C.N.s 6696 & 6700)

Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten,

March 1932, page 70

From Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany):

‘The mate in three was published in Nimzowitsch’s

chess column on page 6 of the Baltische Zeitung

of 11 December 1918, in an article dealing with

smothered mate. (Note that the white king is on c1.)

A number of articles from Nimzowitsch’s column in

that publication were reprinted in my article “Aaron

Nimzowitsch und die Baltische Zeitung” in Kaissiber,

October-December 2007, pages 54-65.’

As an addition to Nimzowitsch the ‘Crown

Prince’ we note the following on pages 179-180 of

The 100 Best Chess Games of the 20th Century, Ranked

by Andrew Soltis (Jefferson, 2000):

‘Aron Nimzovich had an ego problem. After Carlsbad,

1929 he added a sign to his apartment door that read:

CANDIDATE FOR THE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP. “So you won’t

forget?”, he was asked. “So that the chess world

doesn’t forget”, he replied.’

No source was offered.

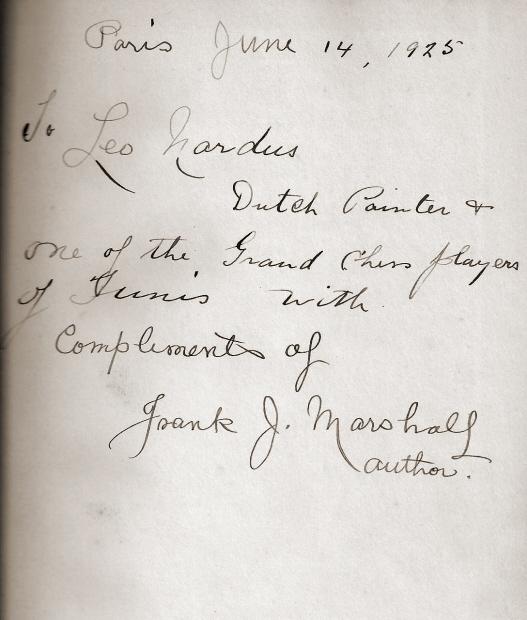

6708. Nardus

Patrick Neslias (Esse, France) provides two photographs

of Léonardus Nardus

from his collection:

Léonardus Nardus (left)

and an unnamed opponent

Left to right: Frank

James Marshall, Léonardus Nardus,

Marie Gendreau (governess) and Pierre Boucherle

(painter and friend of Nardus)

Mr Neslias informs us that in October 2010 his book Butin

Nazi, dealing with Nardus’ final period in

Tunisia, will be published by Geste éditions.

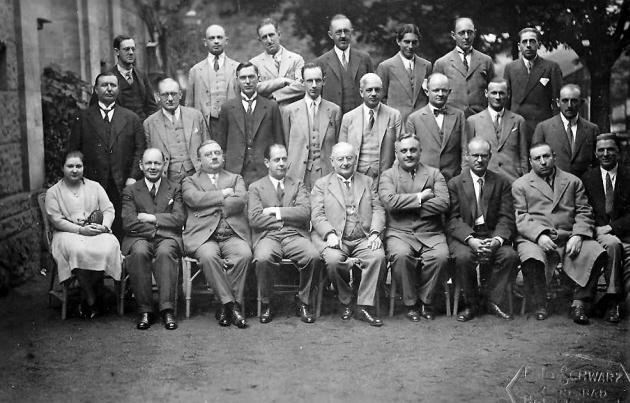

6709. Additional pictures

We are grateful to Patrick Neslias (Esse, France) for

additional illustrations from his collection, including

two Marshall items and the ‘other’ Carlsbad, 1929 group

photograph (which was referred to in C.N. 5372):

6710. Rubinstein in Brussels

Concerning Akiba

Rubinstein’s Later Years Martin Weissenberg

(Savyon, Israel) draws attention to a passage on page

123 of Histoire des maîtres belges by M. Wasnair

and M. Jadoul (1988):

‘Après la guerre, O’Kelly et Devos rendaient

régulièrement visite à Akiba Rubinstein qui avait

élu domicile à Bruxelles. Malade, absent, les yeux

éteints, le grand A. Rubinstein reprenait vie devant

l’échiquier. Comme le contait Devos, “ses yeux

s’allumaient sitôt l’échiquier installé”. Rubinstein

et O’Kelly ont joué ensemble des dizaines de parties

sur le même thème: 1 é4 é5 2 Cf3 Cc6 3 Fb5 Fç5 (le

système Cordel de la partie Espagnole). L’étude

approfondie de cette variante où O’Kelly conduisait

toujours les noirs, deviendra l’une de ses armes

favorites. L’enseignement des parties jouées avec A.

Rubinstein, mais surtout son travail personnel,

permettront à O’Kelly de passer du niveau de bon

maître national à celui de maître international et

enfin à celui de grand maître.’

Did either O’Kelly or Devos write any articles about

their meetings with Rubinstein?

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) notes that on

page 7 of the 16 December 1908 issue of the New York Evening

Post Emanuel Lasker gave a version of the

seventh match-game between Marshall and Mieses (played

in Berlin on 28 November 1908) which deviated from the

commonly-published score.

Lasker’s text was repeated on page 63 of the December

1908-January 1909 issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine,

and for reasons of legibility that is the version

reproduced here:

The game-score as regularly presented elsewhere is

below (with, in square brackets, observations by Mr

Blackstone on the differences from Lasker’s version):

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 c5 4 cxd5 exd5 5 Nf3 Nc6 6 g3

Be6 7 Bg2 Nf6 8 Bg5 Be7 9 dxc5 Qa5 10 O-O Qxc5 11 Rc1

O-O 12 e4 Qa5 13 Bxf6 Bxf6 14 exd5 Rad8 15 Qb3 Bxd5 16

Nxd5 Rxd5 17 Qxb7 Nd4 18 Nxd4 Rxd4 19 a3 Rd2 20 b4

Qxa3 21 Bd5 Bc3

22 Bxf7+ [‘22 Rb1 Rb2 23 Rxb2 Qxb2 24 b5 Qe2 25

Bxf7+ Kh8 is the line given by Lasker.’] 22...Kh8

23 Rb1 Rb2 24 Rxb2 Qxb2 25 b5 Qe2 [‘Now the lines

come back together.’] 26 Qxa7 Qxb5 27 Qe3

Qb4 28 Bd5 Bd4 29 Qe2 Qb2 30 Qxb2 Bxb2 31 Kg2 Rd8 32

Rb1 Rxd5 33 Rxb2 h5 34 f4 Kh7 35 Kh3 g5 36 Rb7+ Kg6 37

Rb6+ Kf5 [‘37...Kg7 38 Rb7+ Kg6 39 Rb6+ Kf5 40 Rh6

was given by Lasker.’] 38 Rh6 h4 39 Rh5 Kg6 40

Kg4 hxg3 41 hxg3 [‘This is where Lasker states

that Black resigned.’] 41…Kf6 42 Rxg5 Rxg5+ 43

fxg5+ Kg6 44 Kh4 Kg7 45 Kh5 Kh7 46 g6+ Kg7 47 Kg5 Kh8

48 Kh6 Resigns.

The 48-move version was given in various magazines of

the time, an example being Deutsches Wochenschach,

13 November 1908, pages 449-450. Even so, Lasker was

in Berlin at the time of the game. His column in the Evening

Post was headed ‘Berlin, 2 December’, and the

introductory text too was reproduced in Lasker’s

Chess Magazine (on page 40 of the

above-mentioned issue).

6712. Barden in the Evening

Standard

Leonard Barden (London) informs us that his daily

(Monday-Friday) chess column in the London Evening

Standard began in early June 1956. Apart from one

week in May 2009 when it appeared online only, the

column continued in the newspaper until 30 July 2010.

Since then, it has been published exclusively online.

Has there ever been, in any journalistic field, such a

run for a daily column by a single individual?

Leonard Barden (Chess

Life, August 1962, page 169)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) sends the

third game in the Judd v Showalter match, as published

on page 5 of the New York Sun, 13 December

1891, and asks whether the score is correct. In

particular, do other sources explain Black’s

resignation or mention 38...Qxd6 and 40...Rd3 as

possibilities?

Max Judd – Jackson Whipps Showalter

Third match-game, St Louis, 10 December 1891

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Bd3 c5 5 Bb5+ Nc6 6 exd5

Qxd5 7 Nf3 Nf6 8 O-O Bxc3 9 bxc3 cxd4 10 Bxc6+ bxc6 11

cxd4 O-O 12 Re1 Nd7 13 Qd3 Rd8 14 Ng5 Nf8 15 Nf3 Ng6

16 c4 Qh5 17 Qe4 Rb8 18 Bf4 Nxf4 19 Qxf4 Ba6 20 Re5

Qg6 21 Rc1 Rb1 22 Ree1 Rxc1 23 Rxc1 Qd3 24 Qc7 Rf8 25

Qxc6 Qa3 26 Re1 Qxa2 27 Ne5 Bc8 28 d5 Qa5 29 Nf3 exd5

30 cxd5 Bg4 31 Rc1 h6 32 Rd1 Rc8 33 Qb7 Qa4 34 Rf1 Qf4

35 h3 Rb8 36 Qxa7 Bxf3 37 gxf3 Rb3 38 d6 Rxf3 39 d7

Qg5+ 40 Kh2 Resigns.

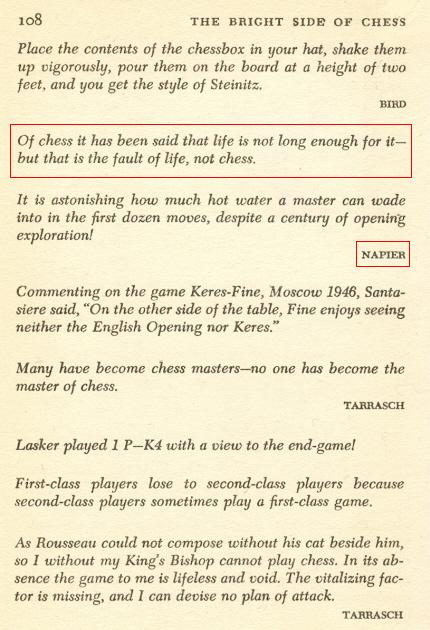

From page 1 of Lessons in Chess, Lessons in Life

by Jose A. Fadul (Morrisville and London, 2008):

‘Somebody complained that life is too short to be

wasted in trivial games such as chess. But William

Napier did retort that such is the fault of life,

and not of chess.’

The retort is indeed sometimes attributed to Napier

(for example, in a piece which appeared under Frank

Elley’s name on page 30 of Chess Life, March

1986), but we do not recall seeing it in Napier’s

writings.

As noted in The Most Famous Chess

Quotations, ‘Life’s too short for chess’ was a

line of dialogue in the play Our Boys by H.J.

Byron. Our feature article on Sir John Simon quoted from

page 116 of CHESS, 14 December 1937:

‘Deputizing for Sir John at the Sheffield Cutlers’

Feast recently, Dr Burgin, Minister of Transport,

referred to the Chancellor’s partiality to chess and

added, “Of chess it has been said that life is not

long enough for it – but that is the fault of life,

not of chess”.’

We commented that the longer quote is often attributed

to Irving Chernev, who gave it (without claiming

paternity) on page 108 of The Bright Side of Chess

(Philadelphia, 1948). Moreover, the book’s layout

created the false impression that Chernev was ascribing

the remark to Napier.

Another case of confusion arising from the layout of

quotes in that section of The Bright Side of Chess

is the ‘conferred sight’ remark attributed to Capablanca

(see C.N. 4209).

On page 313 of the October 1969 BCM D.J. Morgan

listed ‘Life is too short for chess, but that is the

fault of life, not chess’ as an unnamed reader’s entry

in a ‘Views on Chess’ competition. It was published on

page 30 of the Observer of 31 October 1937.

In the above-mentioned BCM item D.J. Morgan

stated that the winning entry in the 1937 Observer

competition was from Professor H.J. Rose:

‘Intimate conversation without a word spoken;

thrilling activity in quiescence; triumph and

defeat, hope and despondency, life and death, all

within sixty-four squares; poetry and science

reconciled; the ancient East at one with modern

Europe – that is Chess.’

This is relevant to the discussion of the quote, and

its author, in C.N. 5462.

A famous remark, it was reproduced on page 17 of The

Big Book of Chess by Eric Schiller (New York,

2006) with only two mistakes (‘quiescent’ and ‘poetry

and signs’).

6716.

Tom

Wiswell

Tom Wiswell has been mentioned in several C.N. items,

and now Gene Gnandt (Houston, TX, USA) draws our

attention to the checkers master’s appearance on an

edition of the television game-show What’s

My Line? broadcast on 21 February 1954

(starting at about 5’30” into the segment).

Robert Sherwood (E. Dummerston, VT, USA) points out

this photograph on page 23 of the February 1921 American

Chess Bulletin:

Justin Horton (Huesca, Spain) comments that many

Internet pages place Nimzowitsch’s alleged lament

about losing to ‘this idiot’ (Sämisch) not in Berlin,

as stated by Kmoch, but at Baden-Baden, 1925.

Half-way through that tournament Nimzowitsch did

indeed lose to Sämisch, but what evidence exists that

such an incident occurred there?

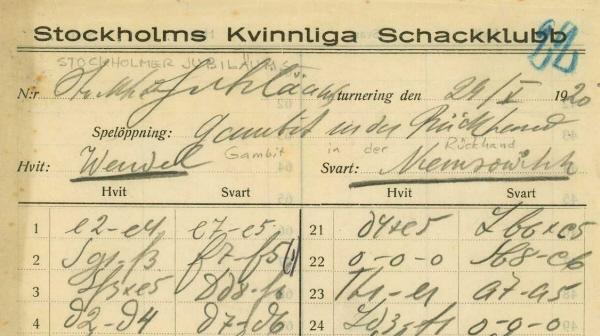

6719. Wendel v Nimzowitsch

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) asks for

information about the exact occasion when the famous

game Wendel v Nimzowitsch (‘Stockholm, 1921’) was

played.

Nimzowitsch described it as ‘one of my best games’, and

it has been widely printed and praised. For instance, on

pages 6-8 of Irving Chernev’s The Golden Dozen

(Oxford, 1976) it appeared with the following

introduction:

‘There are deep, dark and mysterious moves in this

exotic game that could only have been produced by a

strange, original genius.’

The game was published (headed ‘Stockholm, 1921’, but

without further details) on pages 8-10 of the

January-February 1922 issue of the Swedish magazine Tidskrift

för Schack, with Nimzowitsch’s annotations:

Acknowledgement: Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) and

Peter Holmgren (Stockholm).

A different set of notes by Nimzowitsch appeared on

pages 148-150 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten,

1 April 1925:

In the German magazine the heading stated that it was a

‘match game’. There was no such reference in a third set

of notes by Nimzowitsch, on pages 128-130 of his book Die

Praxis meines Systems (Berlin, 1930):

In none of these publications did Nimzowitsch identify

White by more than his surname, but the player is almost

certainly Verner Wendel (1893-1940), who has an entry in

Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia. He was active

in Stockholm chess circles during the period in question

and participated in a tournament in that city, with

Nimzowitsch, in October-November 1920. From page 203 of

the November-December 1920 Tidskrift för Schack:

That same issue had Nimzowitsch’s notes to games by

Wendel against Olson and Spielmann, but neither of

Nimzowitsch’s victories against Wendel in the tournament

was given. Nor has any reference to a Nimzowitsch v

Wendel match been found in the Swedish magazine or

elsewhere.

It may thus be wondered whether the Wendel v

Nimzowitsch game under discussion was, in fact, played

in the Stockholm tournament of October-November 1920,

and not in 1921 as stated by Nimzowitsch. In that case,

though, Nimzowitsch could have been expected to publish

‘one of my best games’ in the Tidskrift för Schack of

the time, i.e. together with his wins against Olson,

Spielmann and Jacobson from the Stockholm, 1920

tournament (which he did annotate in the

November-December 1920 edition of the magazine).

However, as shown above, his notes to the Wendel v

Nimzowitsch game were not published until the

January-February 1922 issue.

If, therefore, the date 1921 for the Wendel v

Nimzowitsch game is correct after all, an event in which

it could have occurred remains to be identified.

6720. Alekhine quotation (C.N. 6704)

C.N. 6704 asked for substantiation of this quote

attributed to Alekhine: ‘There must be no reasoning from

past moves, only from the present position.’

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) refers to

comments by Alekhine in his 1938 radio interview (see

C.N. 5838): ‘Look forward all the time is the thing to

do.’ ... ‘I never look back on a game or a match but try

all the time to see how I may improve my play.’

From Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) comes an

article ‘Ce que nous disait Alekhine!’ by Louis

Betbeder, which was published in a brochure for the 1967

French championship. One piece of advice by Alekhine (in

Betbeder’s reported speech and under the heading ‘Objectivité

du jugement’) was:

‘Savoir si l’on est mieux que l’adversaire est,

par conséquent, essentiel; se poser très souvent la

question, en particulier pendant qu’il réfléchit.

Juger surtout une position en oubliant complètement

l’histoire de la partie et en ne considérant que la

géographie, c’est-à-dire le diagramme actuel.’

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) mentions

that a better copy of the Reshevsky photograph can be

viewed in the Cleveland

Public Library Digital Gallery.

A question from Calle Erlandsson

(Lund, Sweden): are any photographs available of the

Scottish player Peter

Reid (1910-39)?

From page 109 of The Bright Side of Chess by

Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

‘Nimzowitsch described someone as “An amateur who

played a weak enough game to enable him to conduct

an important chess column”.’

Chernev gave no further details, but the words

appeared on page 261 of Nimzowitsch’s book The

Praxis of My System (London, 1936). The

translation, by J. du Mont, omitted the name of the

columnist in question, but it had been given on page

180 of the original edition, Die Praxis meines

Systems (Berlin, 1930):

The name also appeared on page 154 of a recent

English translation (by Ian Adams) of Nimzowitsch’s

book, published under the title Chess Praxis

(Glasgow, 2007):

The report of Wilhelm Therkatz’s death on page 12 of

the January 1925 Wiener Schachzeitung stated

that he had conducted the chess column in the Krefelder

Zeitung for 26 years.

6724. Wood v Ritson Morry

Our Chess in the Courts

article quoted the following from page 161 of CHESS,

August 1954:

‘Chess Criminal Charge

B.H. Wood was acquitted at Birmingham Assizes on 14

July, without calling upon any evidence, of a charge

of criminal libel instituted by W. Ritson Morry. In a

letter to a Mr Golding, Mr Wood had indicated that if

Mr Morry was in the new Welsh Chess Union, Mr Wood was

out; he referred to Mr Morry as “this ex-gaolbird”. It

was held that Mr Wood was entitled to give his reasons

for withdrawing; that the description was true, as

Morry, after misappropriating clients’ money as a

Solicitor some years before, had been sentenced to 18

months’ imprisonment.

The Commissioner stated that in his opinion the case

should never have been brought, and awarded B.H. Wood

costs not exceeding £100.’

James Plaskett (Cartagena, Spain) asks whether further

details are available on Ritson Morry’s offence.

We note from Google

Books (snippets shown by a search for ‘Ritson

Morry’ and ‘solicitor’) that 1940s law reports had

information on the case. Could a reader with access to

the documents supply an account of the proceedings?

‘Every chess master was once a beginner’ is an

observation regularly credited to Irving Chernev.

Where did he write it?

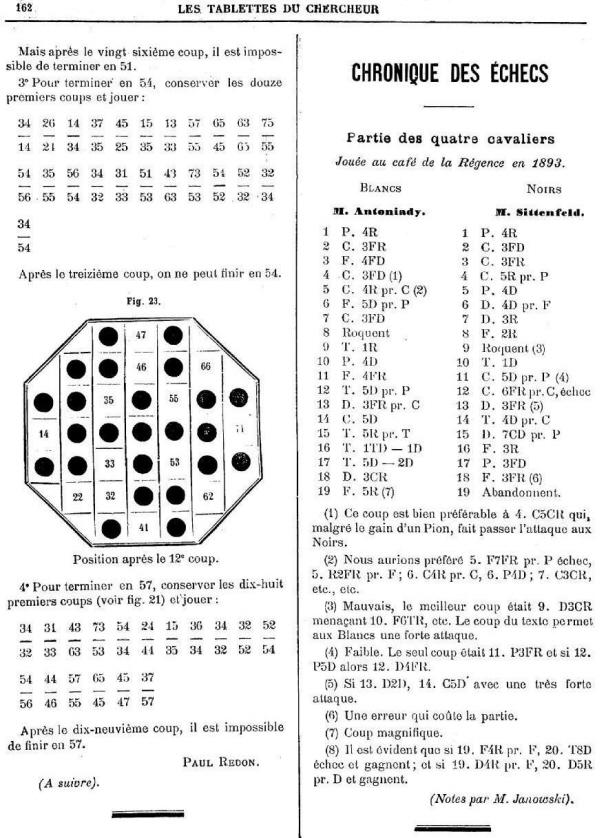

Rick Kennedy (Columbus, OH, USA) is seeking more

information about a game which we reproduced in C.N.

2860 from page 79 of Beadle’s Dime Chess

Instructor by M.J. Hazeltine (New York, 1860):

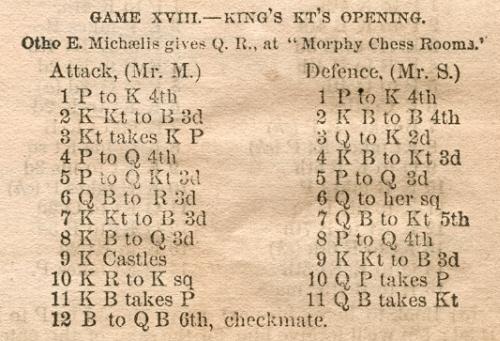

Otho E. Michaelis – ‘Mr S.’

New York (date?)

(Remove White’s queen’s rook.)

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Bc5 3 Nxe5 Qe7 4 d4 Bb6 5 b3 d6 6 Ba3

Qd8 7 Nf3 Bg4 8 Bd3 d5 9 O-O Nf6 10 Re1 dxe4 11 Bxe4

Bxf3

12 Bc6 mate.

6727.

B. Niemzowitsch

C.N. 2273 (see page 26 of A Chess Omnibus)

asked for biographical information about the problemist

B. Niemzowitsch and gave this mate-in-three from page

587 of Die Schwalbe, November 1933:

We have received the following from Per Skjoldager

(Fredericia, Denmark), who, as mentioned in C.N. 3506,

is co-authoring with Jørn Erik Nielsen a book on Aron

Nimzowitsch:

‘Aron Nimzowitsch had three younger brothers, and

Benno (or Benjamin) was the youngest. He was born on

14 May 1896 (new style) and by the first of his two

marriages he had a son, Isay-Erik (born in Berlin on

28 July 1928). Benno lived in Berlin for several

years, before moving to Langfuhr, Danzig. He was a

strong chessplayer as a boy but put his efforts into

problem composition. Because of his Jewish

background, he had to flee from the Nazis, and he

finally went back to Riga. The Nazis killed the

entire family in 1941.

Benno Niemzowitsch

(photograph courtesy of Per Skjoldager)

In our collection we have more than 30 problems by

Benno Niemzowitsch. For the most part they are

self-mate compositions, but there are also a few

direct-mate problems. His first composition on

record was published in the Baltische Zeitung

of 2 October 1918, in Aron Nimzowitsch’s chess

column (“Erstabdruck”):

Mate in four

When this problem was given on page 95 of Skakbladet,

June 1936 the pawn on g7 was missing, and the

composition was ascribed to Aron Nimzowitsch.’

Mr Skjoldager informs us that the Nimzowitsch book

mentioned in the previous item is due to be published

in 2011 and he adds:

‘An early game between Benjamin Blumenfeld and

Aron Nimzowitsch, Berlin, 1903 (1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6

3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nxc6 bxc6 6 Bd3 d5 7 e5 Ng4

8 O-O Qh4 9 h3 h5 10 Bf4 Bc5 11 Qd2 Rb8 12 Nc3 Rb4

13 Bg5 Qg3 14 hxg4 hxg4 15 Rfe1 Rh2 16 Bf1 Rh8 17

Bd3 Rh2 18 Bf1 Bxf2+ 19 Qxf2 Rh1+ 20 Kxh1 Qxf2 21

Re2 Qg3 22 Rd1 Bf5 23 Nxd5 cxd5 24 Rxd5 Rb8 25 e6

fxe6 26 Rxf5 Kd7 27 Rf7+ Kc6 28 Rxe6+ Kb7 29 Kg1

Resigns) can be found on the Internet, but we have

not been able to trace a source for it.

We believe that it is probably a “real game”,

partly because Nimzowitsch played this particular

variation of the Scotch Game in his youth and

partly because he was acquainted with Blumenfeld

during his early years in Berlin. We have looked

through all possible chess columns and all

contemporary German periodicals, as well as

Blumenfeld’s books, without success, but the game

may have been published by him in a Russian/Soviet

chess magazine. Can anyone find it?’

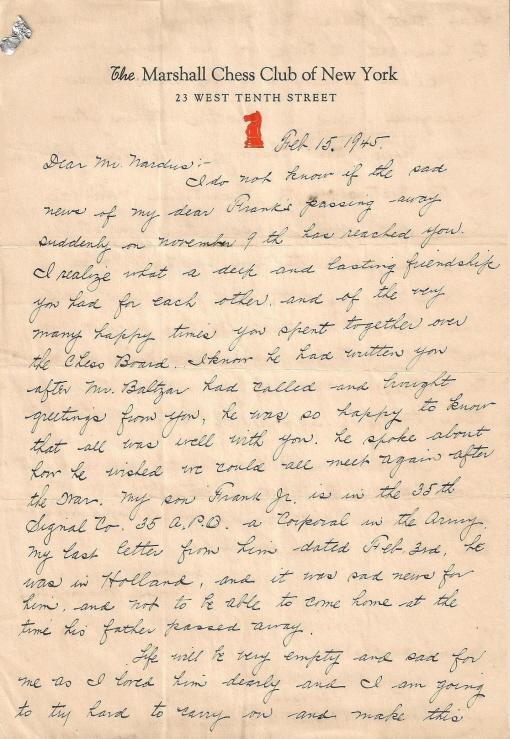

6729. Caroline Marshall letter

Patrick Neslias (Esse, France) provides from his

collection a letter sent by Caroline Marshall to

Léonardus Nardus announcing her husband’s death:

Below is the photograph referred to by Mrs Marshall,

reproduced from page 2 of the December 1944 Chess

Review:

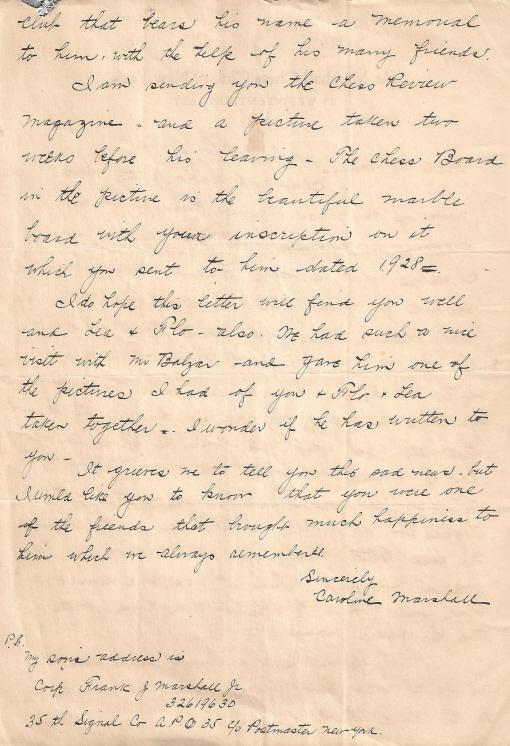

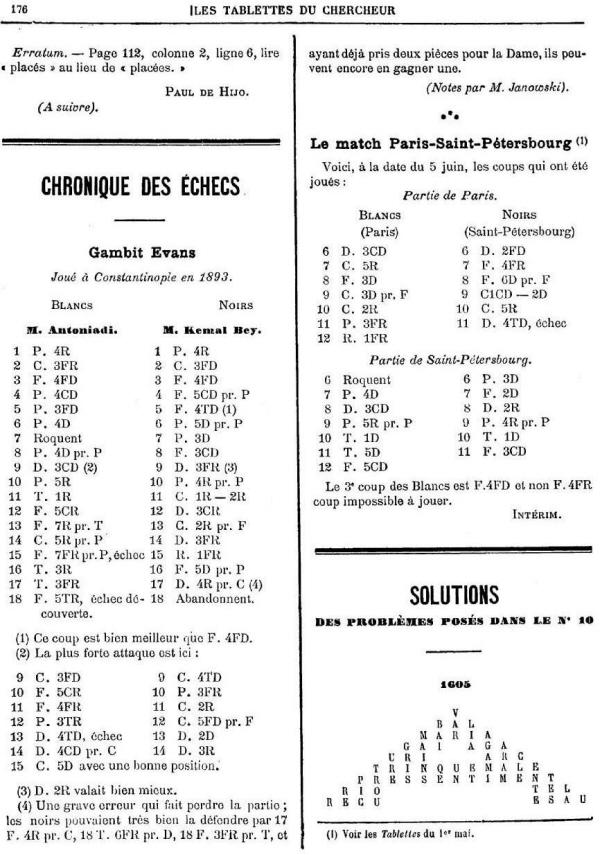

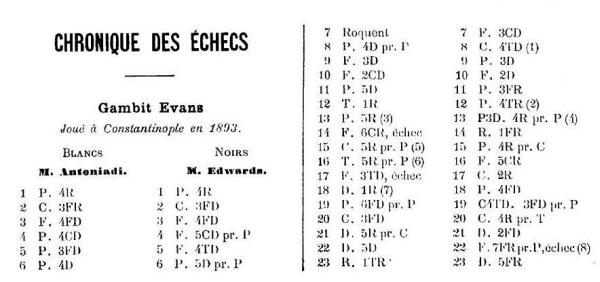

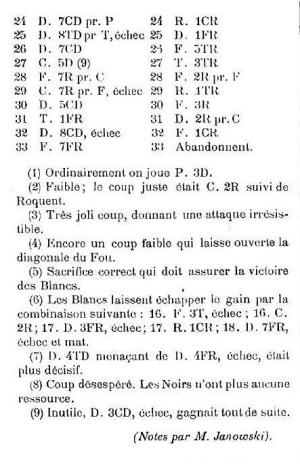

Further to our feature article on E.M. Antoniadi,

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) has submitted

three games published in Les tablettes du chercheur

in 1894 (pages 162, 176, 194 and 195):

6731. Lasker problem

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) sends a

straightforward problem (mate in three) composed by

Emanuel Lasker for young solvers which was published on

page 32 of the Neue Freie Presse, 22 December

1935:

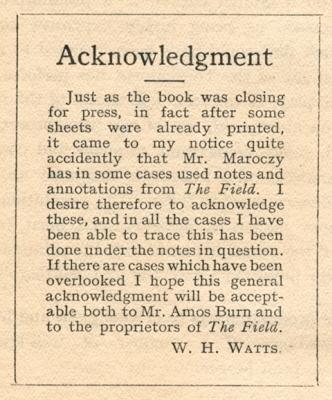

A serious disservice is done to chess history by some

‘modern’ editions of old tournament books. The latest

example is London 1922 by G. Maróczy (Milford,

2010), which not only discards the original book’s

introductory material but brushes out the editor and

publisher, W.H. Watts, and a master, Amos Burn, who

annotated at least 18 of the games.

In the original edition, games featuring Burn’s

annotations (games 41-44, for example) ended with the

specific reference ‘Notes from The Field’:

On page 5 of the original edition Watts gave an

explanation indicating that the total number of games

annotated by Burn, as opposed to Maróczy, might well

be even higher than 18:

David McAlister (Hillsborough, Northern Ireland)

inform us:

‘There are a number of Law Reports on the

criminal proceedings brought against Ritson Morry.

However, they all report not the trial itself but

his unsuccessful appeal against conviction heard

by the Court of Criminal Appeal on 29 October

1945. His grounds of appeal were essentially

concerned with legal technicalities, and the

judgment of the three-judge Court of Criminal

Appeal (delivered by Mr Justice Hilbery) does not

go into details about the criminal charges which

Morry faced. It merely states:

“At the summer assizes at Birmingham, on 26 July

1945, the appellant was tried on an indictment

containing four counts charging him with

fraudulent conversion of four sums of money

totalling £3,136. He was convicted on all counts,

and sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment.”

This passage appears on page 633 of Volume 2 of the

All England Reports for 1945. The complete

report is on pages 632-636 and was cited by lawyers

as R. v Morry [1945] 2 All ER 632.’

6734.

Young masters

From page 168 of the July-August 1931 Kagans

Neueste Schachnachrichten:

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) has found an

article by Louis Mandy on pages 51-52 of the May-June

1955 issue of L’Echiquier de Paris. Entitled ‘La

Rennaissance Echiquéenne’, it discussed the

chess magazine of that name, which was edited by

Gesztesi/Gestesi during its brief run (March-July

1912).

Mandy’s article included some biographical

information about him and this picture, a detail from

a photograph taken during a simultaneous exhibition in

Sceaux on 24 November 1911:

Paul Timson (Whalley, England) provides further

details:

‘As mentioned by David McAlister in C.N. 6733,

the only references to Ritson Morry in the Law

Reports relate to a decision of the Court of

Criminal Appeal on 29 October 1945, before

Hilbery, Wrottesley and Stable, the appeal being

based on technical legal grounds. I offer a

summary below.

At the summer assizes at Birmingham on 25-26

July 1945 the appellant, William Ritson Morry, a

solicitor, was tried on an indictment containing

four counts charging him with fraudulent

conversion of four sums of money totalling £3,136.

He was convicted on all counts and sentenced to 18

months’ imprisonment.

He appealed against his conviction on a number

of technical legal grounds and represented himself

at the Court of Criminal Appeal.

One of the grounds of appeal was that when he

was committed for trial by the magistrates’ court

the magistrates, as they were obliged to do, asked

him the question laid down by statute: “Do you

wish to say anything in answer to the charge? You

are not obliged to say anything unless you desire

to do so, but whatever you say will be taken down

in writing and may be given in evidence upon your

trial.”

In response to that question he took the

opportunity to make a speech, lasting some three

hours, as an advocate on his own behalf. He now

appealed on the grounds that because every word of

his speech was not taken down and certified, the

committal was irregular and the whole indictment

should have been quashed.

The Court of Criminal Appeal held that the

procedure of calling upon the accused to make a

statement if he chooses at that stage in the

proceedings, where the magistrates are considering

whether or not a case is made out for committal,

was never intended to apply to a man making an

oration as an advocate on his own behalf. They

therefore dismissed this ground of appeal.

Another ground of appeal was that the

magistrates had refused to commit him for trial on

the charges which were the subject of counts one

and two in the indictment. The trial judge had,

however, decided that these counts should be

included in the trial, as well as counts three and

four (on which the magistrates had committed him),

and the appellant was duly convicted on all four

counts.

The Court of Criminal Appeal held that this was

a matter for the trial judge to decide, and his

decision could not be questioned.

The appeal was therefore dismissed, and the

Court held that the sentence of 18 months’

imprisonment would run from the date of

conviction, namely from the first day of the

assizes (25 July 1945).

The Wood v Ritson Morry case was reported in the

Times newspaper on 7 April 1954, when B.H.

Wood was committed for trial, and on 15 July 1954,

when he was acquitted on the charge of criminal

libel.

The offending paragraph of Wood’s letter to

Henry Golding, dated 23 February 1954, was quoted

by the Times:

“Your whole attitude makes it clear that you are

a Morry stooge. When you have become in due time

disillusioned about this ex-gaolbird and have

returned to sanity please contact me again unless

you are so fed up that you drop out of chess

altogether as some have done.”

The 7 April 1954 report in the Times

stated:

“Mr Morry said that at one time he practised at

Sutton as a solicitor. ‘I fell on evil times,

however, and was sentenced to 18 months’

imprisonment for fraudulent conversion, which I

served and returned to public life’, he said. He

had put himself at right with the world and was

entitled to live at peace with it. The use of the

expression ‘ex-gaolbird’ with its highly

defamatory meaning was in itself sufficient to

maintain a conviction for criminal libel,

submitted Mr Morry.”

That report also quoted two officials of the

British Chess Federation, Sir Leonard Swinnerton

Dyer and George Wheatcroft, as stating that they

were aware of Morry’s past conviction but had had

no objection to his holding office in the

Federation.

From personal knowledge I can give a fuller

answer to James Plaskett’s question in C.N. 6724.

I studied law at Birmingham University from 1965

to 1968 and whilst there I played in the

Birmingham chess league at a time when B.H. Wood

and W. Ritson Morry (both also graduates of

Birmingham University) were still playing in the

league. I had several long conversations with

Wood, who was President of the University Chess

Club and, as I recall, it was he who told me the

story of Ritson Morry’s downfall. In the late

1930s Ritson Morry, who was a solicitor, invested

clients’ money without their knowledge or consent

in a speculative property development. He was

convinced that the development would make a large

profit and he would be able to replace the

clients’ money and take the profit for himself.

Unfortunately for Ritson Morry, with the outbreak

of the Second World War the development collapsed

and he lost all the money which had been invested.

As he was unable to replace his clients’ money

from his own resources, they reported the matter

to the police as soon as they became aware of the

situation, and this resulted in his eventual

conviction and imprisonment, and also in his being

struck off the roll of solicitors.

He did eventually repay the money.’

The photograph below (showing the English players who

went to Holland to play a Dutch team) comes from page

296 of the June 1937 BCM:

6737. Wendel v Nimzowitsch (C.N. 6719)

C.N. 6719 asked whether the Wendel v Nimzowitsch game

under discussion (which began 1 e4 Nc6 2 d4 d5) was

perhaps played in the double-round tournament in

Stockholm, October-November 1920.

Maurice Carter (Fairborn, OH, USA), who has a book on

Nimzowitsch in progress, informs us that that

possibility can be discounted, given that he owns

Nimzowitsch’s score-sheet of the game against Wendel in

which Nimzowitsch was Black. The heading provided by our

correspondent is shown below:

From pages 222-223 of ‘Garry Kasparov on My Great

Predecessors Part I with the participation of

Dmitry Plisetsky’ (London, 2003):

‘To the super-tournament in New York (1927),

arranged to “accommodate” Capablanca, Lasker was no

longer invited.’

Zenón Franco Ocampos (Ponteareas, Spain) asks whether

this is true. The answer is no, because Lasker was

invited to New York, 1927.

We discussed the matter on pages 195-197 of our book

on Capablanca, referring to the bitter public dispute

which had arisen at New York, 1924 between Lasker and

Norbert Lederer (the latter being a key figure on the

organizing committees of New York, 1924 and New York,

1927).

Much additional information was presented in the

article ‘New York 1927 Documentary Evidence Answers

Lingering Questions’ by Hanon Russell on pages 88-104

of the first issue of the American Chess Journal

(1992). A section of the article (pages 99-101) was

headed ‘Why Didn’t Lasker Play?’, and it showed that

although the New York, 1927 organizing committee did

not believe that Lasker would participate, Lederer ...

‘... made an extraordinary effort to convince

Lasker to play. He enlisted the help of influential

people in the United States and Europe, but Lasker

was not persuaded. Finally, as the plans which were

formulated had to be finalized, Lederer made one

last effort. On 10 December 1926 he wrote a

five-page typewritten letter in German to Lasker

(Russell Collection #584). Lederer, whose first

language was German (he was born in Vienna), wanted

to make absolutely certain that he would not be

misunderstood. Lederer’s formal invitation to Lasker

specified all the terms, financial and otherwise,

being offered to Lasker as well as a strong plea for

Lasker to relent and play in what was recognized

even then as one of the world’s great chess

tournaments.’

Lasker refused the invitation.

See also pages 74 and 640 of Emanuel Lasker:

Denker Weltenbürger Schachweltmeister edited by

R. Forster, S. Hansen and M. Negele (Berlin, 2009).

Richard J. Hervert (Aberdeen, MD, USA) and Alan

McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) comment that the caption in

Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten is faulty,

since Pirc is standing second from the right. (A

photograph of the young Pirc was given in C.N. 6131.)

On the subject of photographs from Kagans Neueste

Schachnachrichten, the following appeared on

page 56 of the March 1932 edition:

Daniël Noteboom

Page 48 of the February 1932 issue stated that the

photograph had been given to Kagan by Euwe.

6740. Morphy at the Opera

Regarding the game Morphy

v the Duke and Count and the correct spelling of

the Count’s name, Kevin O’Connell (Mouret, France)

informs us:

‘1. Vauvenargues (Vauvenarga or Vauvenargo in the

Provençal language, which was still dominant in the

area in the 1870s) is a village in Provence.

Vauvenargues is the French version, but the village

is located in Occitania and so has its Occitan name,

but there are six dialects, of which Provençal is

one. Within Provençal there are two orthographical

norms, one of which gives “Vauvenargo” and the other

“Vauvenarga”. The latter would almost certainly be

favoured today.

2. The château, bought by Picasso in 1958,

belonged to the Isoard family from 1790 to 1943.

Information is available under “Histoire et

patrimoine” at the website of the Mairie de

Vauvenargues.

3. In all variants of Occitan (including

Provençal) “o” is invariably pronounced “ou” unless

it has a grave accent (ò), in which case it should

be pronounced like the “o” in Opéra.

4. In spelling the Count’s name today, there is

certainly some latitude, but I suppose that it

should officially be Comte Isoard de Vauvenargues,

in recognition of the considerable success of the

French authorities (during the approximate period

1870-1930) in almost stamping out the language of

the people of the southern half of France, even

though it is 99% certain that his name was

pronounced “Isouard”.’

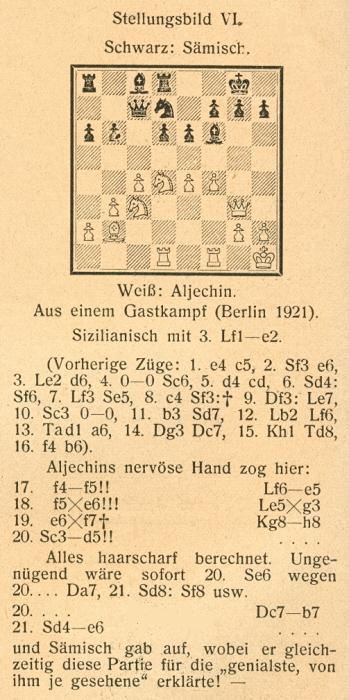

Pages 14-15 of 100 Classics of the Chessboard

by A.S.M. Dickins and H. Ebert (Oxford, 1983) gave

Alekhine v Sämisch, Berlin, 1923 under the heading

‘The Classic Blindfold Game’. The co-authors claimed:

‘Happening to meet in Berlin, the two players

decided to take the opportunity of playing each

other blindfold, creating as a result this

astonishing brilliancy.’

The book added that Sämisch called Alekhine’s victory

‘the most brilliant game I have ever seen’. The moves:

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Be2 e6 4 O-O d6 5 d4 cxd4 6 Nxd4

Nf6 7 Bf3 Ne5 8 c4 Nxf3+ 9 Qxf3 Be7 10 Nc3 O-O 11 b3

Nd7 12 Bb2 Bf6 13 Rad1 a6 14 Qg3 Qc7 15 Kh1 Rd8 16 f4

b6 17 f5 Be5 18 fxe6 Bxg3 19 exf7+ Kh8 20 Nd5 Resigns.

It is one of Alekhine’s most spectacular miniatures,

number 97 in his first collection of Best Games (London,

1927). The heading was ‘Exhibition Game played at

Berlin, February 1923’. The book did not suggest that

either master was blindfold. Nor did the German

translation, Meine besten Partien 1908-1923

(Berlin and Leipzig, 1929), although we have one later

edition in German (Berlin, 1983), which states ‘Beiderseits

ohne Ansicht des Brettes’. Various editions of

the book Meisterspiele by Rudolf Teschner say

that both players were without sight of the board, and

Sämisch’s praise of Alekhine is quoted:

‘“Die genialste Partie, die ich je gesehen

habe”, äußerte Sämisch voll Bewunderung für seinen

Gegner.’

As shown below, Tartakower cited Sämisch when he

published the game (a ‘Gastkampf’ , which

Tartakower dated 1921, instead of 1923, with no

intimation of blindfold play but with an additional

move at the end) on page 276 of Die hypermoderne

Schachpartie (Vienna, 1924):

January, rather than February, 1923 was specified

when the game appeared on pages 218-219 of the second

volume of Complete Games of Alekhine by V.

Fiala and J. Kalendovský (Olomouc, 1996). The

co-authors asserted that the game was first published

on page 16 of the Observer, 4 March 1923. In

neither that volume nor in the Skinner/Verhoeven book

on Alekhine (see page 184) was it suggested that

Alekhine or Sämisch played the game blindfold.

Moreover, the score was not included in Blindfold

Chess by E. Hearst and J. Knott (Jefferson,

2009).

The brilliancy is absent from all the chess magazines

of 1923 that we have consulted so far.

6742. William Hartston in Now!

Throughout the run of the weekly news magazine Now!

(September 1979-April 1981) there was a fine chess

column by William Hartston. Some quotes are offered

below:

- ‘... combinations are much easier to find if you

know they are there. If only those magic words “White

to play and win” would light up below the board, we

would all win so many more games. In real life most of

the sacrifices are not correct; only the fantasy world

of the chess columnist has flashy finishes to games

...

Some years ago I was playing in the Hastings

tournament with Mikhail Tal. One evening, he picked up

an English newspaper, casually glanced at the chess

column and started laughing. What had attracted his

attention was the position given for readers to solve:

it was from his own game against Platonov played at

Dubna in 1973.

The amusement, however, was caused by the set of par

solving times appended in order to rate one’s

achievement in finding the answer. These began at 20

seconds, indicating grandmaster strength, then

proceeded via master, county player and club player to

stop at “average” – five minutes. “That’s very funny”,

said Tal. “I spent 15 minutes looking at the position

before I saw it, and my opponent didn’t see it at

all.”’ (4-10 January 1980, page 98.)

The position in question was given:

White (Tal) to move

- ‘You can tell a great deal about a chessplayer by

the way he looks at the board when it is his turn to

move. Spassky always wears the bored expression of a

man in a bus queue, in no particular hurry. Korchnoi,

on the other hand, looks as though he is in danger of

missing his train, while Karpov has the confident pose

of one who knows that the train will wait for him even

if he is late. But this week, we shall be talking

about Polugayevsky. He looks as though he is the only

one with a timetable, cannot understand why the bus

was not there ten minutes ago, and is about to panic

and run for a taxi.’ (11-17 July 1980, page 88.)

- ‘Modern grandmasters, of course, are far superior in

technique and understanding, but games from the

distant past have a feeling of spontaneous enjoyment

and a quest for brilliance which is generally lacking

in today’s sophisticated world. ...

Such a game as this [the famous Steinitz Gambit

brilliancy won by Robert Steel from the 1880s] gives

the impression that calculating ability and

imagination in chess are no better now than they were

100 years ago. The game is far more scientific, of

course, but for sheer flair and inventiveness such

nineteenth-century brilliancies remain practically

unparalleled in modern play.’ (25-31 July 1980, page

88.)

- ‘I met the eponymous professor [Arpad E. Elo] during

the chess olympics at Nice in 1974. He was besieged

with requests by players wanting the rules bent to

accommodate their own requests for international

titles. When the last of the supplicants had gone,

Professor Elo said to me: “I think I have created a

monster.” I think so too.’ (1-7 August 1980, page 82.)

- ‘Even when games are annotated by the players

themselves, most fall victim to the temptation to

justify their decisions rather than explain them.

Chess is not a precise science or even a totally

logical game. Only after the result is decided do the

annotators feel obliged to present the decisions in

black and white. ...

All the more enjoyable therefore to come across the

rare example of totally honest annotators of their own

games. Of today’s great players I put complete trust

in Larsen and Tal.’ (8-14 August 1980, page 82.)

- ‘One reason for the wide appeal of chess lies in the

ambiguous nature of the game. Some claim it is a

sport, others view it as a science while many try to

elevate chess to the level of art. I have always taken

the view that chess is primarily a sport masquerading

as a minor art form.’ (3-9 October 1980, page 80.)

- ‘Some time ago the great Russian player David

Bronstein gave me this advice: “Look at the games of

Gordon Crown. He really understood chess”.’ (6-12

February 1981, page 80.)

6743. Michaelis gamelet (C.N.s 2860

& 6726)

John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) notes that the gamelet

was published in the New York Clipper, 8

September 1860, introduced as follows:

‘An exceedingly curious mate given by our contributor

Otho E. Michaelis giving QR.’

From Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) comes

a report on page A10 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle,

16 May 1929:

‘Lasker-Lederer Settlement

The judiciary committee of the National Chess

Federation, of which Judge Jacob E. Dittus of

Chicago is chairman, has adjudicated the controversy

between Dr Emanuel Lasker of Berlin, former world’s

champion and winner of first prize in the

international masters’ tournament in New York, 1924,

and Dr Norbert L. Lederer, director of that

tournament, according to advices received from

Chicago.

Dr Lederer had lodged a formal complaint against Dr

Lasker with the committee to the effect that Dr

Lasker had published statements reflecting upon his

character, as well as upon the executive committee

of that tournament, and which, he declared, called

for an apology. Dr Lasker, it is said, agreed to

abide by the findings of the judiciary committee.

The committee decided that Dr Lederer’s complaint

was justified and that the facts in the case did not

bear out Dr Lasker’s accusation. A report of the

findings was sent to Dr Lasker.

Edward Lasker, recently elected secretary of the

National Chess Federation, said yesterday that he

and other friends of Dr Emanuel Lasker felt certain

that the latter will acquit himself gracefully by

publicly retracting his charges. Dr Lasker became 60

years of age on 24 December last, an occasion which

was fittingly celebrated by the chessplayers of

Germany.’

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) refers to a game

given in databases as won by Emanuel Lasker (White) in

a simultaneous exhibition in the Netherlands in 1908

against C.A. Moller:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 d3 Bc5 5 Nc3 d6 6 Be3

Bb6 7 Qd2 O-O 8 O-O Be6 9 Nd5 Bxd5 10 exd5 Ne7 11 Bg5

Ng6 12 Nh4 Nxh4 13 Bxh4 Ne4 14 dxe4 Qxh4 15 Bd3 g6 16

Kh1 f5 17 g3 Qf6 18 f3 f4 19 g4 Rf7 20 Rae1 Qh4 21 Re2

g5 22 Rg2 Kg7 23 c4

23...Rd8 24 b4 Bd4 25 Qc2 b6 26 a4 Kf6 27 Qe2 h5 28

Rc1 Rh7 29 Rc2 Qh3 30 Ra2 Bc3 31 b5 hxg4 32 Rxg4 Be1

33 Rg2 Bg3 34 Rd2 Bxh2 35 Rxh2 Qg3 ‘1-0’.

Noting that the game was given in Lasker’s column on

page 7 of the New York Evening Post, 1 August

1908 as played in Copenhagen at 15 moves an hour, with

Lasker as Black against C.A. Möller, our correspondent

asks, ‘Do you know the truth?’

This is a further example of the unreliability of

databases. The game as given in the Evening Post

also appeared on pages 99-100 of Lasker’s Chess

Magazine, September 1908. Lasker won as Black,

and the game, played in Copenhagen, did not occur in a

simultaneous display.

Moreover, both the newspaper and the magazine had

Black’s 23rd move as ‘QR-R’, i.e. 23...Rh8 and not

23...Rd8 as given in the databases. With 23...Rh8 the

game’s conclusion makes sense.

Chess Notes Archives

Copyright: Edward Winter. All

rights reserved.

|