Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [89] | next >> | Current column |

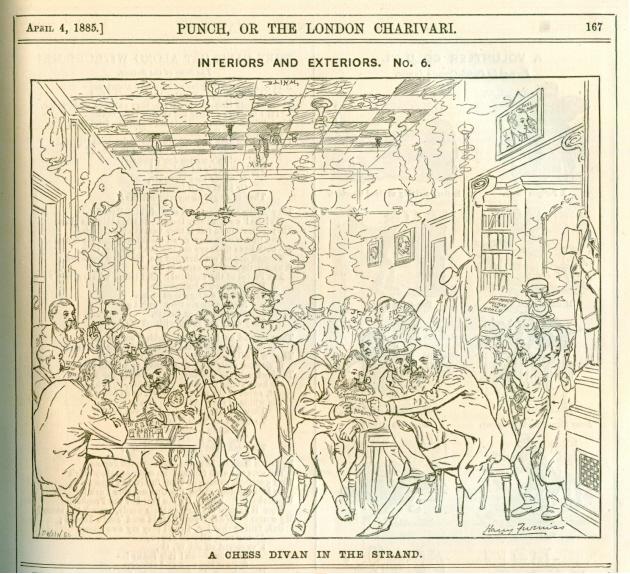

7384. Punch cartoon

This cartoon was discussed on pages 151-154 of The Knights and Kings of Chess by G.A. MacDonnell (London, 1894).

7385. Six-move game

1 f4 e5 2 fxe5 d6 3 exd6 Bxd6 4 g3 Qg5 5 Nf3 Qxg3+ 6 hxg3 Bxg3 mate.

Labelled ‘N.N. v Du Mont’ and dated 1802, this game is often given unquestioningly in chess databases. (It is in the nature of most chess databases that they give unsubstantiated, dubious or inaccurate material unquestioningly. Careful corrective work would surely be a better use of anybody’s time than, for instance, involvement in those inconsequential yet pestilential ‘discussion groups’.)

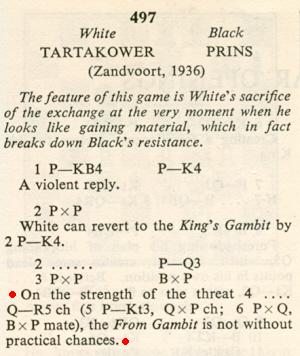

But what is the truth about the above game? For now, we merely note that a similar finish appeared on page 649 of 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (London, 1952):

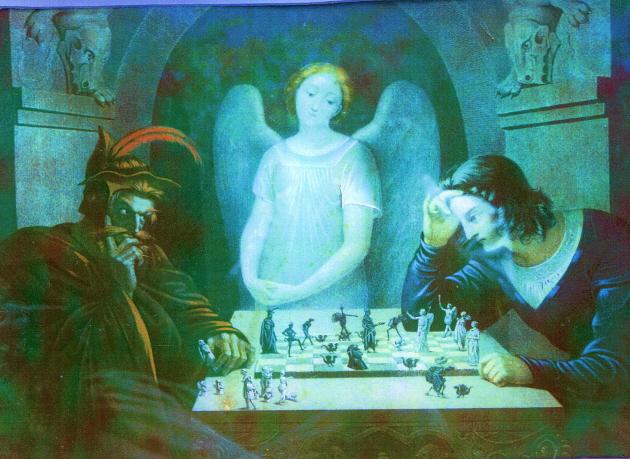

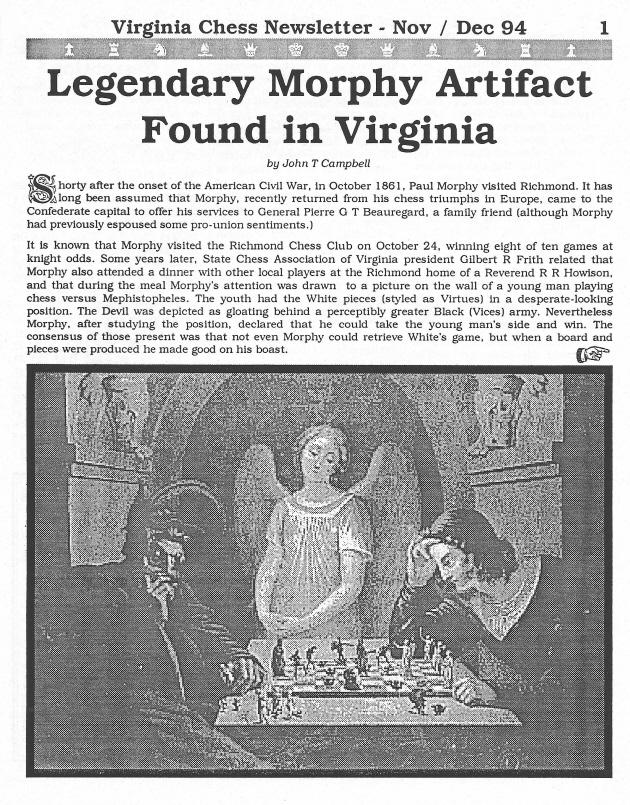

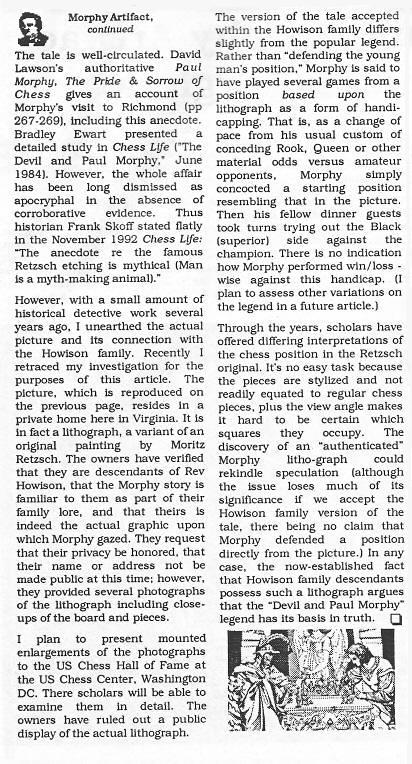

7386. Morphy against the Devil (C.N. 7363)

The Editor of Virginia Chess, Macon Shibut (Vienna, VA, USA), authorizes us to reproduce an article by John T. Campbell which was published on pages 1-2 of the magazine’s November-December 1994 issue:

Our correspondent has also provided the picture in colour:

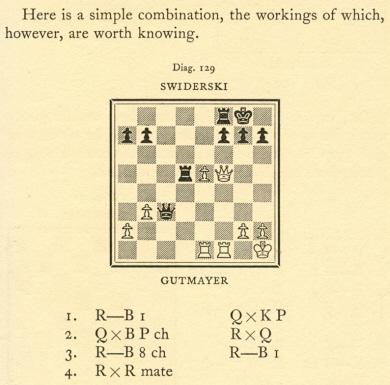

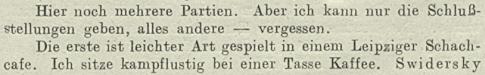

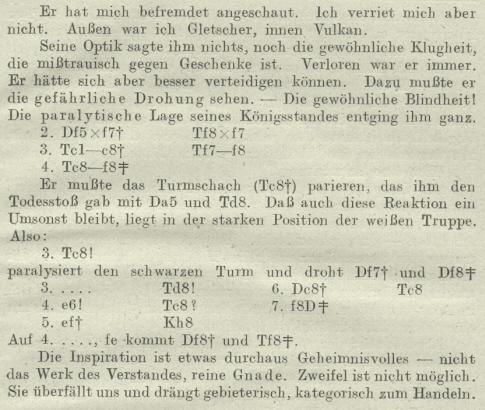

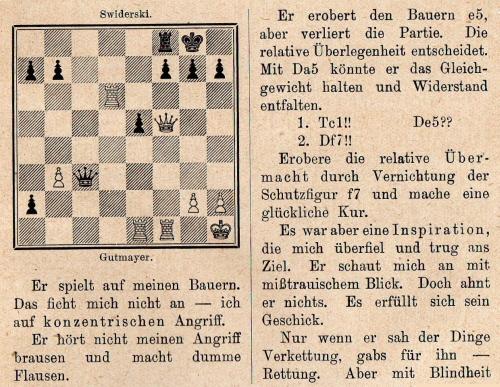

7387. Gutmayer v Swiderski

From page 109 of The Basis of Combination in Chess by J. du Mont (London, 1938):

A similar position (with Black’s queen’s-side pawns on a6 and b5) was on page 52 of Modern Chess Tactics by L. Pachman (London, 1970).

The complete game, played in a Leipzig chess café, appears to be lost, but Gutmayer gave the conclusion (with a position lacking a white rook) on pages 263-265 of the third edition of his book Der Weg zur Meisterschaft (Berlin and Leipzig, 1919):

On pages 115-116 of his book Turnierpraxis (Berlin and Leipzig, 1922) Gutmayer also included the position, with even more errors:

As a postscript, we wonder what is known about the Gutmayer v Lasker game in the second Turnierpraxis diagram above. To begin with, which Lasker was Black?

7388. Fischer and the House of Representatives

In the United States in March 1986 the House of Representatives passed a Resolution, sponsored by Charles Pashayan, which recognized Bobby Fischer as the world chess champion. Siegfried Hornecker (Heidenheim, Germany) provides a link to the record of the Resolution.

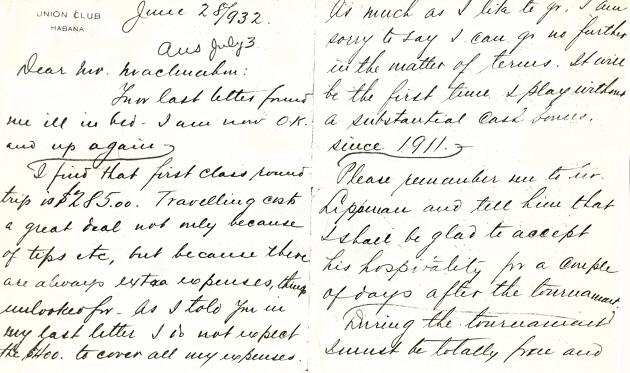

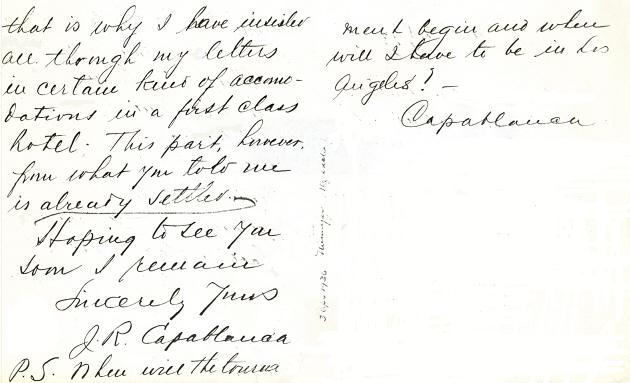

7389. Pasadena, 1932

The recent publication by Caissa Editions

of Pasadena 1932 International Chess Tournament by

Robert Sherwood, Dale Brandreth and Bruce Monson (Yorklyn,

2011) prompts us to reproduce a letter from Capablanca to

Henry MacMahon (which is referred to on page ii, and whose

full text was transcribed on pages 232-233 of our book on

the Cuban):

7390. Cased image (C.N. 6018)

The picture purportedly depicting Morphy, with an unidentified opponent, was the subject of an article by Enoch Nappen on page 25 of the June 1986 Chess Life.

7391. Gutmayer and Lasker (C.N. 7387)

Shortly after posting C.N. 7387 we saw the Lasker game on pages 259-263 of Gutmayer’s book Der Weg zur Meisterschaft (Berlin and Leipzig, 1919). Gutmayer gave the first 28 moves, with the heading ‘Gutmayer u. Genossen – Dr. Em. Lasker’. On page 70 of The Collected Games of Emanuel Lasker by K. Whyld (Nottingham, 1998) the consultants were named as Schlesinger and Thalheim, and the occasion was given as Berlin, 28 February 1896. Gutmayer’s book was not mentioned, and the source was specified as ‘Daniuszewski manuscript [Lothar Schmid]’. Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) notes that the game-score is in a number of databases, dated 6 March 1896, and that on page 116 of Gutmayer’s Turnierpraxis (C.N. 7387) the diagram was incorrect. The latter point is also made by Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany), who adds that the complete game-score was published on pages 113-114 of the 12 April 1896 issue of Deutsches Wochenschach. It was one of three consultation games played simultaneously at the Café Kaiserhof in Berlin on 28 February that year.

We add that Gutmayer also gave the game, naming Schlesinger and Thalheim, on pages 121-122 of his book Die Grosse Offensive am Schachbrett (Innsbruck-Mühlau, 1916).

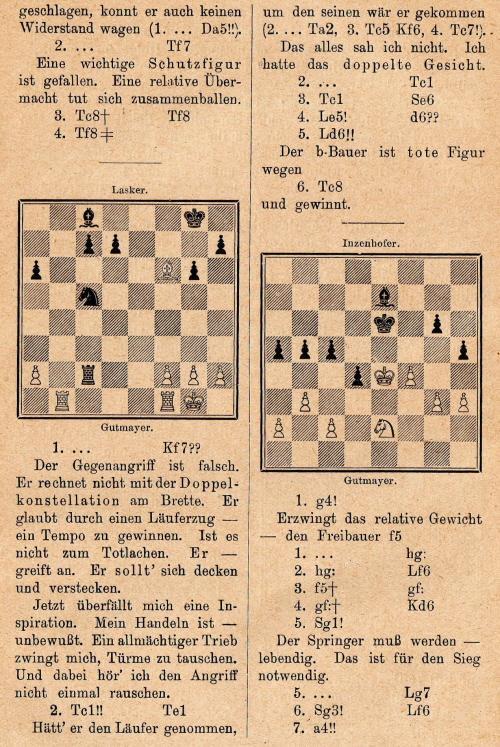

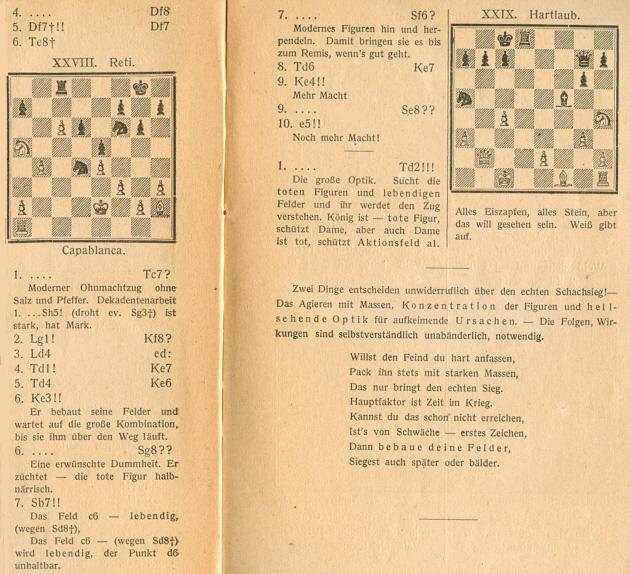

7392. More diagram trouble

Below is another example of Gutmayer’s output, from

pages 20-21 of his book Der fertige Schach-Praktiker

(Leipzig, 1923):

In the Capablanca v Réti game (London, 1922) neither player overlooked that the Cuban’s king was in check. It was on e1, and the white rook was on c1, not a1. Black had a pawn on b5.

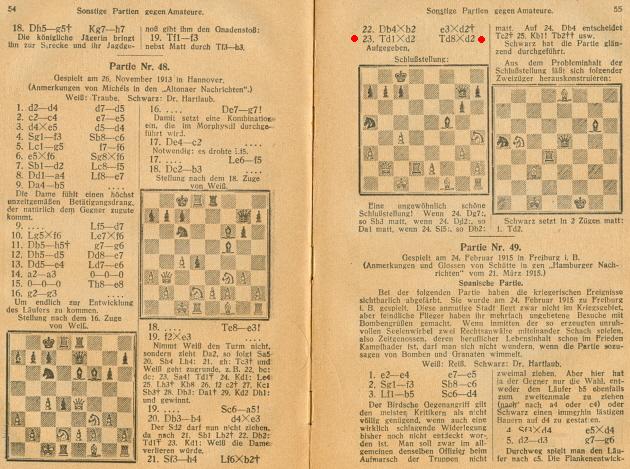

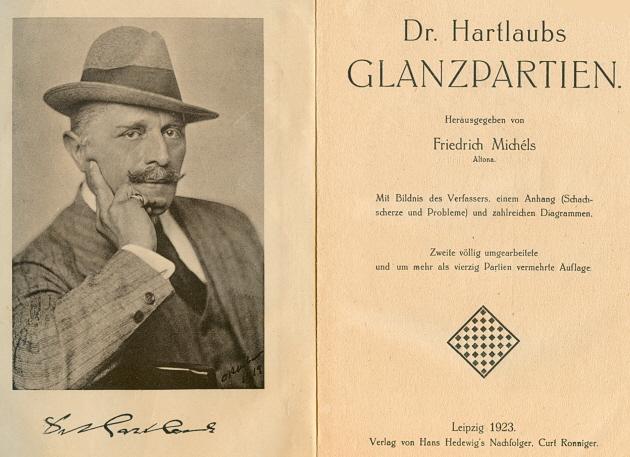

Nor is the Hartlaub position correct; the black rook did not move to an empty square but captured a white rook on d2. The full game (Traube v Hartlaub, Hanover, 26 November 1913) was given on pages 54-55 of Dr. Hartlaubs Glanzpartien by Friedrich Michéls (Leipzig, 1923):

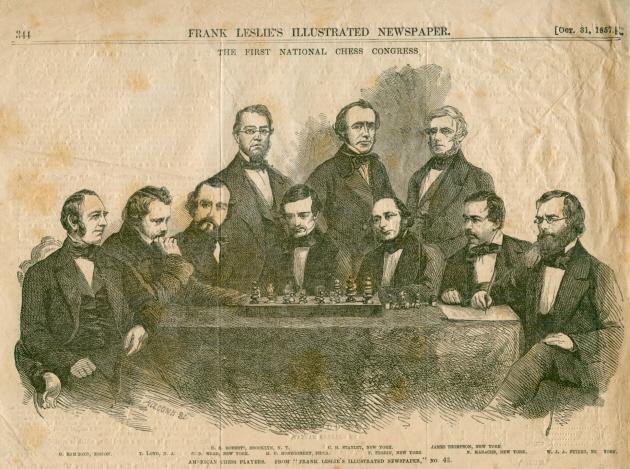

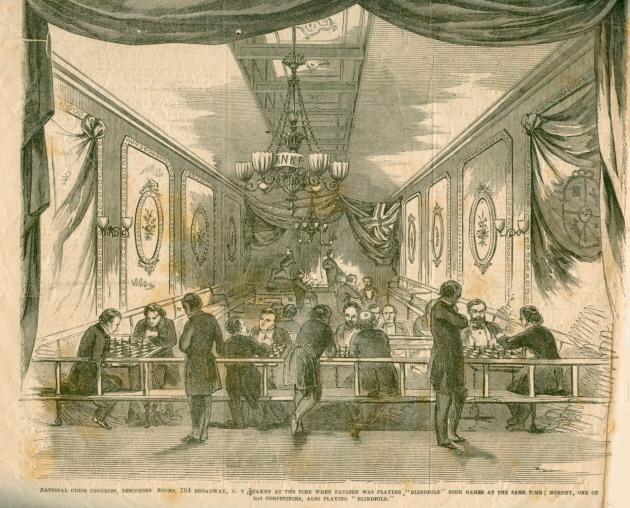

7393. New York, 1857

From our brittle edition of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 31 October 1857 (page 344):

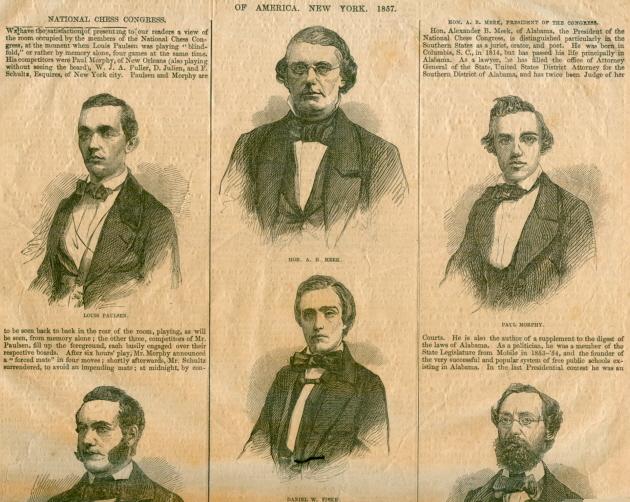

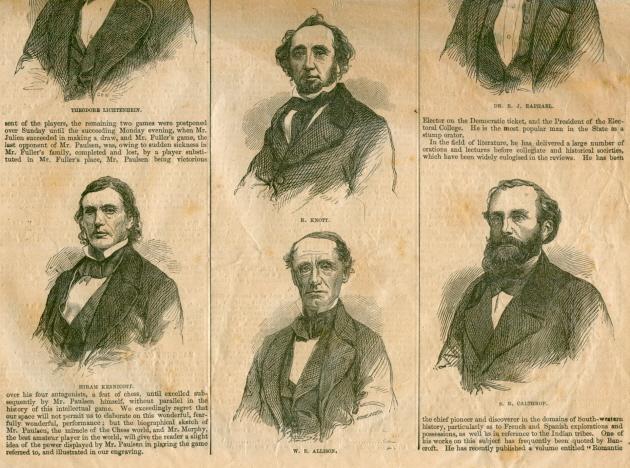

7394. New York, 1857 (C.N. 7393)

These sketches appeared on page 345 of the 31 October 1857 issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper:

Larger versions of section one and section two

7395. Prokofiev

There are many brief references to chess in Sergei Prokofiev Soviet Diary 1927 and Other Writings translated and edited by Oleg Prokofiev (London, 1991). See pages 30, 79, 85, 122, 127, 168, 232, 247, 272 and 306.

From page 272:

‘... I went to New York to be followed shortly by the Chicago Opera Company, which, after several postponements, gave a single performance of the Oranges on 14 February 1922. Owing to these changes in the date of the performance I happened to have a piano recital as well on the day of the opening. Since I was to conduct the opera that evening I followed Capablanca’s advice and spent the time between the recital and the opera taking a hot bath and resting.’

See too the feature article Sergei Prokofiev and Chess.

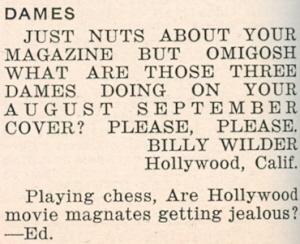

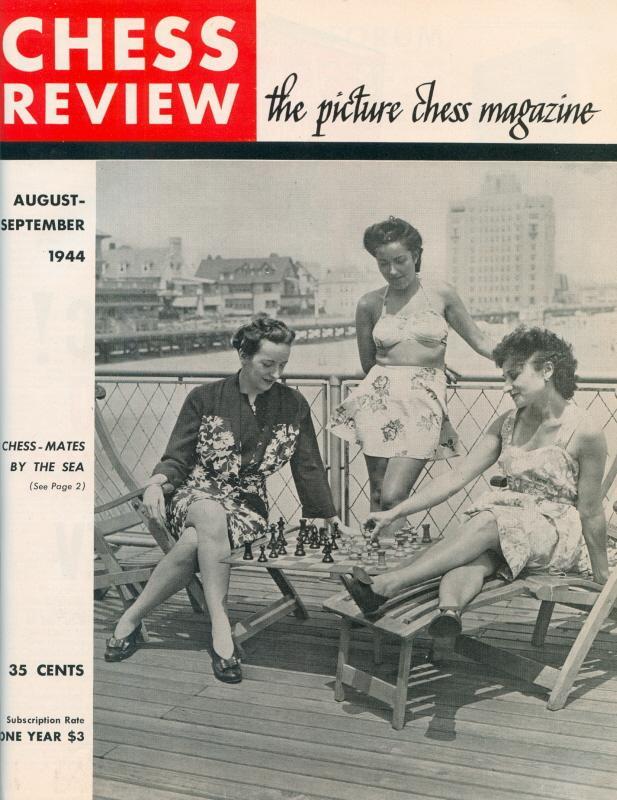

7396. From Billy Wilder

The readers’ letters section of the November 1944 Chess Review included the following:

The front cover to which he was referring:

Page 2 identified the group as comprising ‘Mrs E.S. Jackson, Jr., Mrs G. Shainswit and Mrs A.S. Pinkus, wives of three of the contestants at the Ventnor City tourney’.

7397. Who? (C.N. 7378)

Correct answers have been received from Leonard Barden (London) and Mike Salter (Sydney, Australia). Before revealing the name, we add a photograph of the mystery figure in more familiar company:

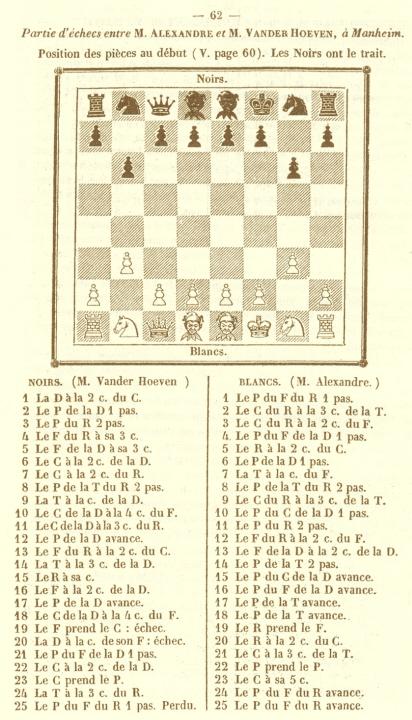

7398. Randomized chess (C.N. 7370)

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) notes a comment about randomized chess on page 365 of Paul Rudolf von Bilguer’s Handbuch des Schachspiels (Berlin, 1843), to the effect that the advantage of openings knowledge could be neutralized by Nieveld’s method of drawing lots to determine the array, although it tended to lead to uninteresting games:

‘Den Vortheil, welchen Jemand aus dem Studium der Eröffnungen erlangt hat, kann man auch auf die vom General Nieveld in seiner Supériorité aux Echecs empfohlene Weise paralysiren. Die Officiere werden nämlich hinter den Bauern gleichförmig auf die erste und achte Reihe, aber in einer durch das Loos bestimmten Ordnung postirt. Es scheint, als sei diese Methode bei den Holländern häufig in Gebrauch, obgleich sie, wie die indische, offenbar den Nachteil hat, gewöhnlich uninteressante Spiele herbeizuführen.’

The Handbuch then gave this specimen game from page 62 of the 15 August 1842 issue of Le Palamède:

van der Hoeven – Aaron Alexandre

Mannheim, 1842

1 Qb2 f6 2 d3 Nh6 3 e4 Nf7 4 Bf3 c6 5 Bc3 Kg7 6 Nd2 d6 7 Ne2 Rf8 8 h4 h5 9 Rd1 Nh6 10 Nc4 b5 11 Ne3 e5 12 d4 Bc7 13 Bg2 Bd7 14 Rd3 a5 15 Ke1 b4 16 Bd2 c5 17 d5 a4 18 Nc4 a3 19 Bxh6+ Kxh6 20 Qc1+ Kg7 21 c3 Na6 22 Nd2 bxc3 23 Nxc3 Nb4 24 Re3 f5 25 f3

25...f4 and wins.

7399. Morphy against the Devil (C.N.s 7363 & 7386)

A further article is ‘The Devil and Paul Morphy – Again’ by Bradley Ewart on pages 26-27 of Chess Life, June 1986.

7400. Keres before AVRO, 1938

The above photograph of Paul Keres was published opposite page 16 of Analysen van A.V.R.O.’s wereld-schaak-tournooi by M. Euwe (Amsterdam, 1938).

From page 82 of CHESS, 14 November 1938 comes a comment written by Paul Keres to B.H. Wood shortly before the tournament began:

‘It will be an achievement not to be last.’

7401. An old problem

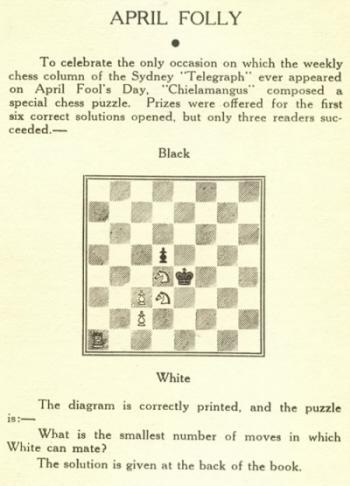

‘What is the smallest number of moves in which White can mate?’

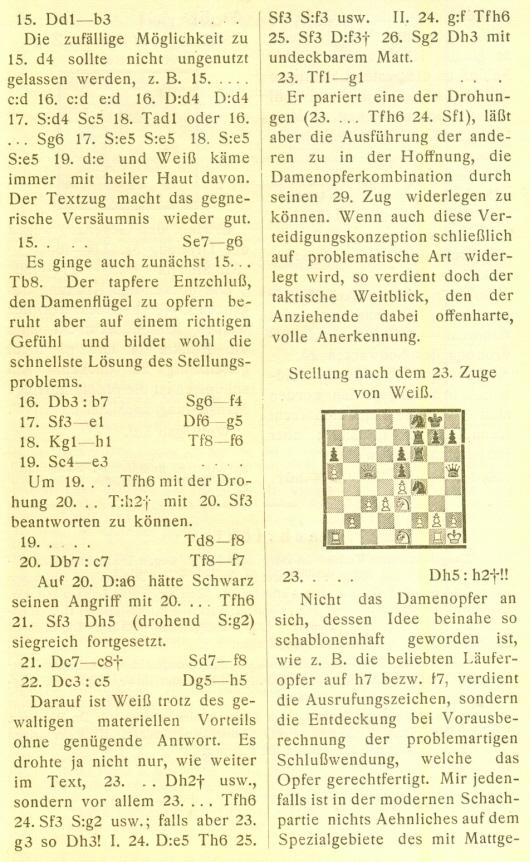

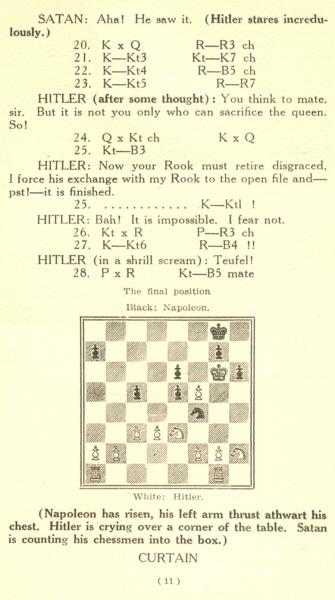

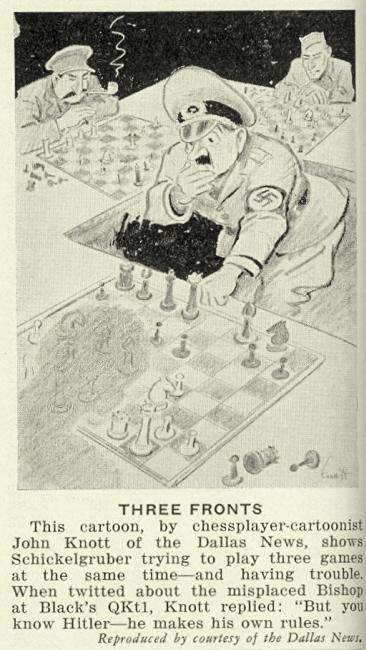

7402. Hitler v Napoleon

An item on pages 178-179 of A Chess Omnibus noted that C.J.S. Purdy attempted to make light of Hitler in a satirical one-act play ‘Hell Hitler’ in “Among These Mates” (Sydney, 1939), a book which he published under the pseudonym Chielamangus. The dramatis personae were Shade of Napoleon, Shade of Hitler, and Satan, and the play was founded on a spoof Hitler v Napoleon game: 1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Bc5 3 Nf3 d6 4 d3 Be6 5 Bxe6 fxe6 6 Be3 Nd7 7 Bxc5 dxc5 8 Nbd2 Ne7 9 O-O O-O 10 Nc4 Ng6 11 c3 Qf6 12 Qb3 Nf4 13 Ne1 Qg5 14 Kh1 Rf6 15 Qxb7 Raf8 16 Qxc7 R8f7 17 Rg1 Qh4 18 Qc8+ Nf8 19 Ne3 Qxh2+ 20 Kxh2 Rh6+ 21 Kg3 Ne2+ 22 Kg4 Rf4+ 23 Kg5 Rh2 24 Qxf8+ Kxf8 25 Nf3 Kg8 26 Nxh2 h6+ 27 Kg6 Rf5 28 exf5 Nf4 mate.

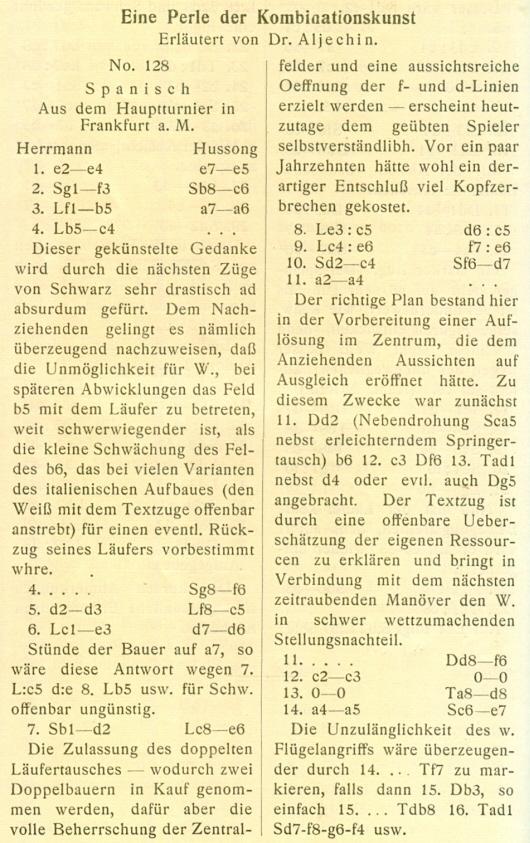

This score was based on the famous brilliancy F. Herrmann v H. Hussong, Frankfurt, 1930 published on pages 314-315 of the October 1930 Deutsche Schachzeitung, October 1930, and, with Alekhine’s notes taken from Denken und Raten, on pages 340-342 of the December 1930 issue of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten:

Below, from Purdy’s book, is the illustration on page 6 and the conclusion of the play on page 11:

In conclusion, we add the following from page 8 of the October 1944 Chess Review:

7403. Who? (C.N.s 7378 and 7397)

The two photographs featured G.S.A. Wheatcroft (1905-87), our source being Twelfth Chess Tournament of Nations by Salo Flohr (Moscow, 1957).

Wheatcroft received an extensive obituary in The Times (5 December 1987, page 10). Headed ‘Authority on taxation law’, it stated that ‘his many books on the subject are of outstanding quality and unrivalled reputation’. Chess was mentioned only in one brief paragraph of the obituary:

‘Wheatcroft was a skilled chess player and represented England at Stockholm, in 1937. He was also a fine bridge player.’

7404. An old problem (C.N. 7401)

From page 27 of “Among These Mates” by Chielamangus (Sydney, 1939):

And from page 79:

7405. Gutmayer’s games against Swiderski and Lasker (C.N.s 7387 & 7391)

In the line of duty we have been browsing further in the books of Franz Gutmayer. Some additional references for the record:

Gutmayer v Swiderski (position only):

- Der Weg zur Meisterschaft (Leipzig, 1913), page 92;

- Die Geheimnisse der Kombinationskunst (Leipzig, 1914), page 17;

- Der Weg zur Meisterschaft (Berlin and Leipzig, 1919), not only pages 263-265 as previously noted but also the title page and page 217;

- Die Geheimnisse der Kombinationskunst (Leipzig, 1922), page 74;

- Der Weg zur Meisterschaft (Berlin and Leipzig, 1923), title page.

Gutmayer et al. v Emanuel Lasker (position only):

- Die Geheimnisse der Kombinationskunst (Leipzig, 1914), pages 38-39;

- Die Geheimnisse der Kombinationskunst (Leipzig, 1922), page 22.

7406. Boden’s mate

1) Schulder v Boden: Black played ...Qxc3+

2) MacDonnell v Boden: Black played ...Qxf3

Regarding the first diagram, our article on Boden’s Mate commented:

‘Page 76 of The Art of Attack in Chess by V. Vuković (Oxford, 1965) gave the position before 14...Qxc3+ (minus the black rook on e8), stating that it came “from the game Macdonell [sic]-Boden (1869)”. That was amended to “Schulder-Boden, London, 1853” on page 76 of the algebraic edition edited by John Nunn (London, 1998). Vuković’s reference to MacDonnell v Boden was evidently based on confusion with another familiar brilliancy by Boden (20...Qxf3) which was also given in the Tartakower/du Mont book (see pages 248-249). Unsurprisingly, there are discrepancies regarding that game too. For instance, page 31 of Combination in Chess by G. Négyesy and J. Hegyi (Budapest, 1965) dated it 1830, the year in which MacDonnell was born.’

We wonder whether Vuković’s mistake was due to copying from Gutmayer, who frequently published the two queen sacrifices. In the list below an asterisk indicates that the games were confused:

- Die Schachpartie (Leipzig, 1913): ‘Macdonnell v Boden’ ...Qxc3+ game on page 174*;

- Der Weg zur Meisterschaft (Leipzig, 1913): ‘Macdonnell v Boden’ ...Qxf3 position on page 42;

- Die Geheimnisse der Kombinationskunst (Leipzig, 1914): ‘– v Boden’ ...Qxc3+ position on page 102;

- Rätsel und Reichtümer der Eröffnung (Leipzig,

1915): ‘Macdonnell v Boden’ ...Qxf3 position on page

102; ‘Macdonnell v Boden’ ...Qxf3 game on pages 198-199;

- Der fertige Schach-Praktiker (Leipzig, 1921): ‘Macdonnell v Boden’ ...Qxc3+ position on page 28*;

- Die Geheimnisse der Kombinationskunst (Leipzig, 1922): ‘Macdonnell v Boden’ ...Qxf3 position on page 15; ‘– v Boden’ ...Qxc3+ position on page 114;

- Turnierpraxis (Berlin and Leipzig, 1922): ‘Macdonell v Boden’ ...Qxc3+ position on page 35*.

Wanted: early sightings of the MacDonnell v Boden game in print.

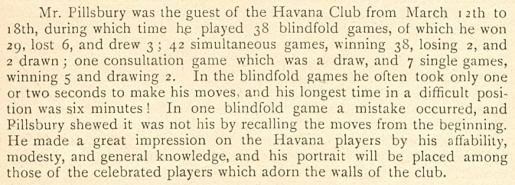

7407. Pillsbury gamelet

The only Pillsbury game in 666 Kurzpartien by

K. Richter (Berlin-Frohnau, 1966) is dated 1900 without

any identification of the opponent or venue: 1 e4 e5 2

Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 d6 4 Nf3 a6 5 Bc4 Bg4 6 fxe5 Nxe5 7 Nxe5

Bxd1 8 Bxf7+ Ke7 9 Nd5 mate. See page 88.

As is well-known, Pillsbury’s opponent (Black) was named Fernández, but where was the game played? There are databases which give ‘Germany’ or ‘Paris’. Page 23 of L’art de faire mat by G. Renaud and V. Kahn (Monaco, 1947) had the venue as Hanover; see too pages 13-14 of the English edition, The Art of the Checkmate.

On the other hand, the information from Renaud and Kahn about the occasion and exact date (a 12-board blindfold display on 16 March 1900) corresponds to what appeared in La Stratégie, 15 May 1900, page 133, and the Wiener Schachzeitung, January 1902, page 11.

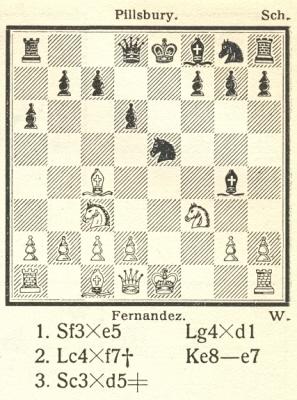

Both magazines stated that the game was played in Havana, and Pillsbury was indeed there in March 1900. From page 231 of the June 1900 BCM:

On page 134 of his book Die Geheimnisse der Kombinationskunst (Leipzig, 1914) Franz Gutmayer blundered yet again, by indicating that Pillsbury lost the game:

7408. N.N. v Morphy

In reply to 1 c3 Black is said to have won with 1...Rxe4 2 Qxe4 Ng3 3 Qxd4 Ne2+ 4 Kh1 Qxh2+ 5 Kxh2 Rh8+ 6 Bh6 Rxh6+ 7 Qh4 Rxh4 mate.

Further details are unknown to us, although the position has been widely published. See, for example, page 403 of Paul Morphy Sein Leben und Schaffen by Max Lange (Leipzig, 1894) and page 431 of Paul Morphy by Géza Maróczy (Leipzig, 1909).

The four editions (1898, 1913, 1919 and 1923) of Der Weg zur Meisterschaft by Franz Gutmayer gave the position as ‘Bousserolle’ or ‘Bonserolle’ v Morphy. See also page 57 of Die Geheimnisse der Kombinationskunst (Leipzig, 1922). A blindfold win by Morphy (as White) against A. Bousserolles is known (the conclusion is on the above-mentioned page of Maróczy’s book), but on what basis did Gutmayer identify White in our diagrammed position?

7409. Gutmayer on Capablanca

Before the Gutmayer books are cleared away, we add some examples of his treatment of Capablanca’s games:

- Pages 281-282 of Rätsel und Reichtümer der Eröffnung (Leipzig, 1915) gave the Cuban’s game against Spielmann at San Sebastián, 1911 but named Spielmann as the winner (White);

- Page 99 of Der fertige Schach-Praktiker

(Leipzig, 1923) stated that Capablanca’s victory

against Sir George Thomas (Hastings, 1919) was played

in New York;

- Page 69 of Der Weg zur Meisterschaft (Berlin and Leipzig, 1923) gave a position in which Capablanca defeated ‘Blackebrond’ (Blackburne);

- Page 99 of the same book was just one of a number of

places where Gutmayer wrongly claimed that Marshall

missed a quick mate against the Cuban (see C.N. 6655).

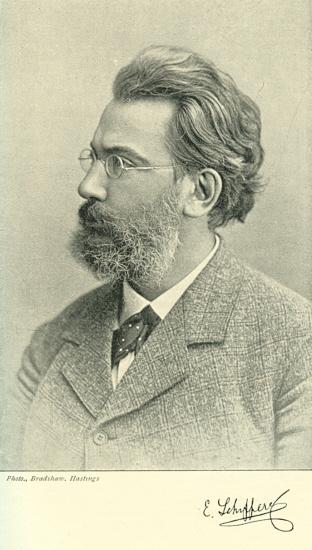

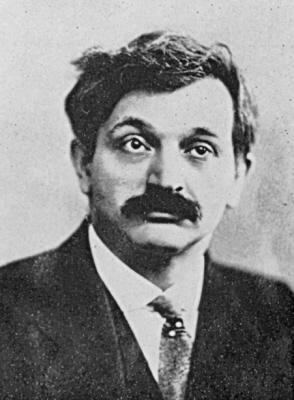

Franz Gutmayer

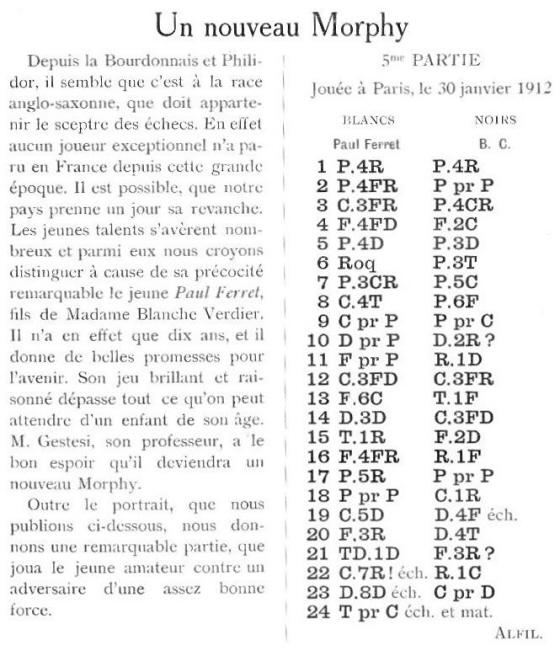

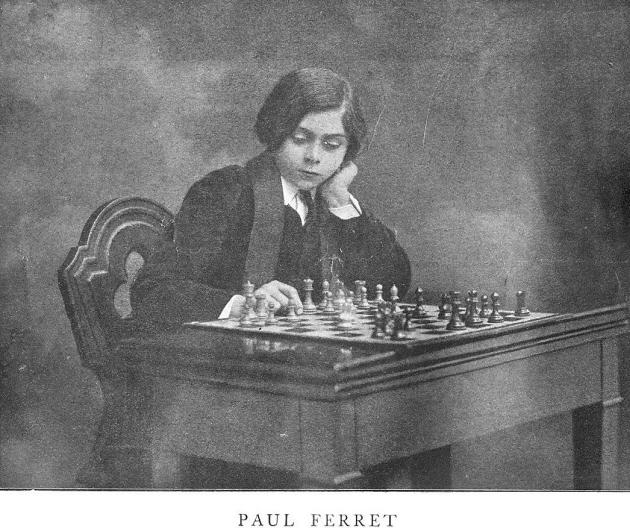

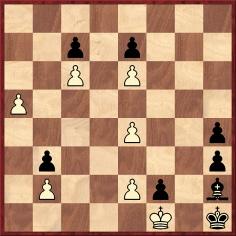

7410. Paul Ferret

The latest addition to Chess Prodigies concerns Paul Ferret, with a game he played in Paris in 1912 at the age of ten.

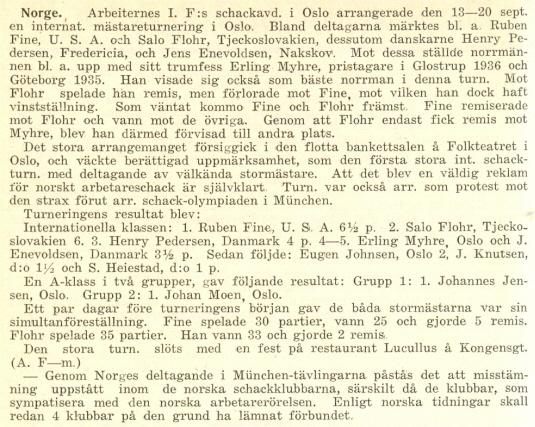

7411. Oslo, 1936

Referring to the Oslo tournament of September 1936, won by Fine ahead of Flohr, Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) asks whether a collection of the games has ever appeared.

We believe not, although all but one of the victor’s games are on pages 115-117 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004).

Below is the report published on page 280 of the October 1936 issue of Schackvärlden:

7412. Punch cartoon (C.N. 7384)

The full text of G.A. MacDonnell’s description of this cartoon by Harry Furniss is available now in A Chess Divan in the Strand.

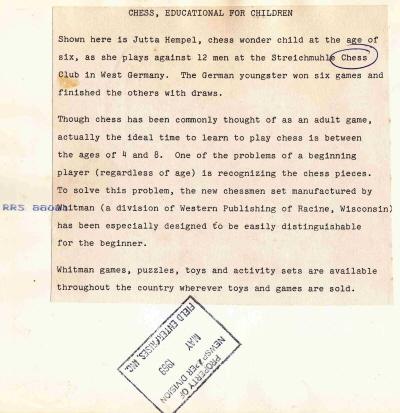

7413. Jutta Hempel

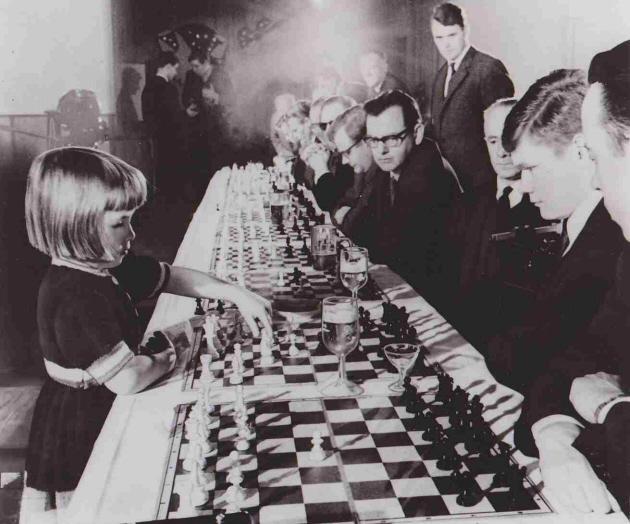

Alain Biénabe (Bordeaux, France) has submitted this photograph of Jutta Hempel, who was born in Flensburg on 27 September 1960:

After the prodigy was first mentioned in C.N., over 25 years ago, Ludwig Steinkohl (Bad Aibling, Federal Republic of Germany) contacted her father, Hermann Hempel of Flensburg, who replied with two long letters giving details of her career. C.N. 1293 presented the following summary, in our translation from the German:

Aged five: 5 June 1966: draw against the Altmeister Chr. Andersen, and also scored a draw against the Danish Jugendmeister Fin Bertelsen. 14 August: lost against H.-J. Hecht.

Aged six: 27 November: at Streichmühle played 12 games simultaneously, scoring 9½ out of 12. November 1966-March 1967: won the Open Junior Championship of Flensburg (Stadt und Land). ‘Jugendmeisterin’ with 7½ points out of 9. March 1967: simultaneous exhibition, scoring 9 out of 10. June 1967: simultaneous games in Flensburg against the Stadtmeister Zimmerman and Ipsen. Scored 1½ out of 2. 13 August 1967 at the ‘Chess Promotion Days’: a) blindfold game which ended in mate on the 46th move. (This was the only blindfold game she played; she gave up on the advice of Brinckmann and others.) b) six-board simultaneous display ‘ohne Fehler’. The arbiter was Ludwig Rellstab. c) victory over the Baden master Dr W. Lauterbach. d) victory over the Stadtmeister W. Hoff from Winsen/Luhe.

Aged seven: Score of 1-1 against Günter Knuth, a Stadtmeister from Oberhausen. 1-0 against Frank Olle. 13 November 1967 at Süderbrarup: played against 22 players in the Schleswig-Holstein Land League. Won six, lost one. The remaining games were adjudicated drawn after midnight. 20-23 November 1968: victory in a problem-solving competition, in only 16 seconds, ahead of Lederer (25 seconds).

Aged nine: Easter 1970. International tournament in Flensburg. Scored 1-1 against Jens Enevoldsen of Copenhagen.

In C.N. 1293 we added:

Mr Hempel gives details of his daughter’s subsequent performances, but it is her early achievements that interest us most. He stresses that no girl aged five-six has matched her chess strength, but he resists the description ‘Wunderkind’. The last time she played was on 2 June 1979, at the Flensburg Lightning Tournament, in which she came first without losing a game. That year she went on to further education in Kiel, in accordance with her own belief, ‘First study, find a profession and then perhaps start playing again’. As she was interested in Business Studies she spent two and a half years as an employee in a Danish bank, after which she continued as a student in Kiel until the end of 1985. In the New Year she started work at the Land Bank in Kiel. On 6 June 1986 she married, and is now called Hempel-Nissen. Today she says: ‘A woman cannot earn a living from chess. But if I have children I will teach them to play, because chess has been a great help to me with everything.’

7414. Weil/Weill/Wiel, etc. (C.N.s 4751, 4755, 4760 & 6954)

From Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada):

‘C.N.s 4755 and 4760 mentioned the connection between Gottlieb Weil and Cambridge, as well as noting that he was a teacher of German. He would appear to be the person referred to on several occasions in Bell’s Life in London well before his matches with Captain Kennedy in Brighton.

The issue of 7 July 1844 (page 2) said of the Cambridge Chess Club that “They possess one very first-rate player in M. Vieile, professor of German in the University. Few players in England come up to this gentleman, who plays also remarkably well without seeing the chess board”. The 28 July 1844 issue (page 2) mentioned “Mr Vial, professor of German, Cambridge”, and the 8 December 1844 issue (page 2) stated: “Since the circumstance of M. Viel taking up his residence at Cambridge, the club is strengthened; this gentleman being well known as one of the best players in London. The Cambridge Club do not authorize us to say this.” Then the 8 June 1845 Bell’s Life in London (page 2) said of the Cambridge Chess Club that “With such players as Professor Weil and the Messrs. Deighton, a first-rate body of players might surely be formed”. The 16 November 1845 issue (page 3) reported: “There is a chess club at Cambridge. Apply to Mr Deighton, the worthy University publisher, or to Mr Viell, the German professor.”’

7415. Morphy picture

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) points out that pages 621-624 of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, March 1888 had an article ‘Chess in America’ by Henry Sedley, with this picture of Morphy on page 621:

For the original oil painting, see page 233 of Paul Morphy The Pride and Sorrow of Chess by David Lawson (New York, 1976).

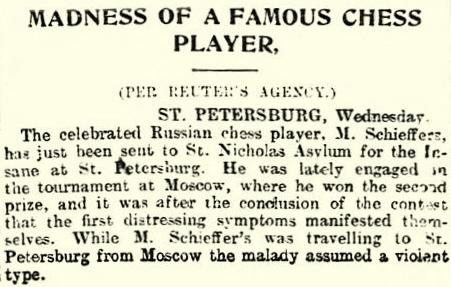

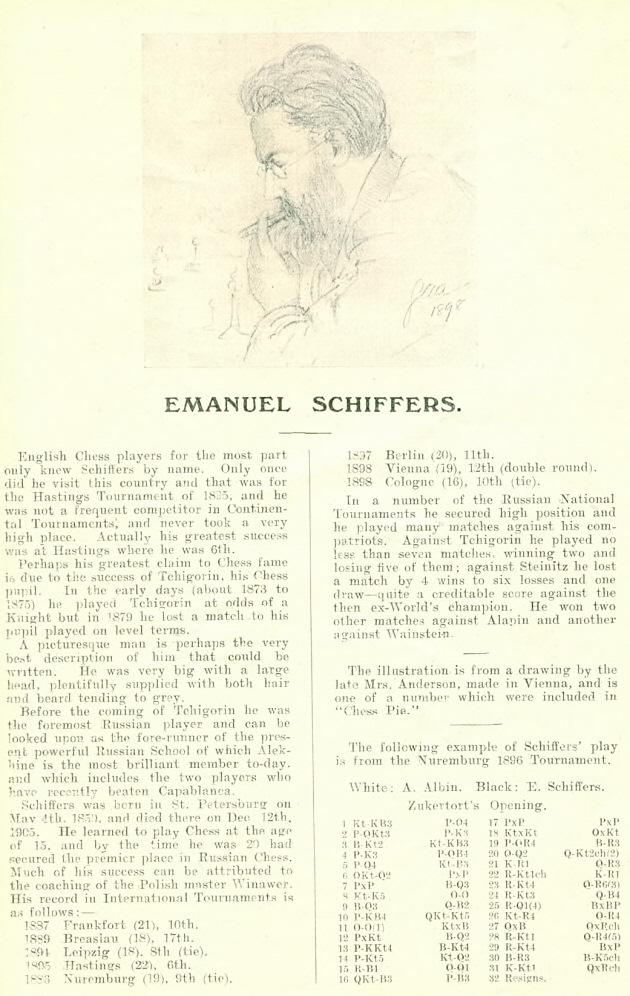

7416. Schiffers

Submitting this cutting from page 7 of the Sheffield Independent, 6 November 1899, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) asks what is known about the claimed health troubles of Emanuel Schiffers (1850-1904):

A photograph of Schiffers from opposite page 48 of the Hastings, 1895 tournament book:

7417. Paul Ferret (C.N. 7410)

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) has forwarded the Ferret game as published on page 20 of the 1-15 March 1912 issue of La Rennaissance Echiquéenne, together with the photograph inserted before page 1:

7418. Knight promotions

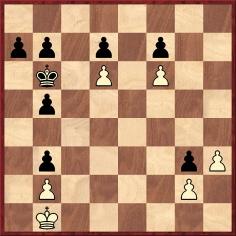

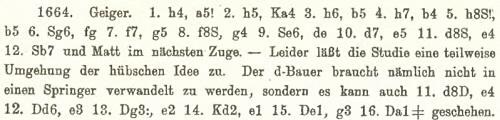

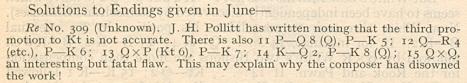

A five-star book just published is The Art of the Endgame by Jan Timman (Alkmaar, 2011). Chapter five is entitled ‘Knight Promotions’, and we became particularly interested in the pair of compositions on pages 82-83:

‘Herland, Deutsches Wochenschach, 1913. White to play and win’

1 a6 Bg1 2 a7 h2 3 a8(N) h3 4 Nb6 cxb6 5 c7 b5 6 c8(N) b4 7 Nd6 exd6 8 e7 d5 9 e8(Q) and wins.

‘F. Fritz. White to play and win’

1 h4 Ka5 2 h5 Ka4 3 h6 b4 4 h7 b5 5 h8(N) a5 6 Ng6 fxg6 7

f7 g5 8 f8(N) g4 9 Ne6 dxe6 10 d7 e5 11 d8(N) and wins.

Regarding the latter composition, Timman commented:

‘It is unclear when this study was made. In the database it has been adorned with the label “source unknown”.

Who was F. Fritz? He should certainly not be mixed up with Jindřich Fritz ...’

The main historical issue raised by Timman is whether Sigmund Herland was the first to compose such a study, in 1913, or whether the Fritz position antedated it. We offer some jottings.

The Herland study was published on page 128 of the 6 April 1913 Deutsches Wochenschach, with the solution on page 247 of the 13 July 1913 issue.

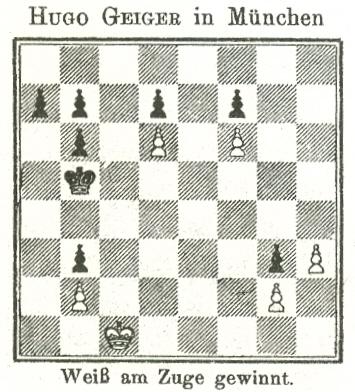

We note furthermore that the endgame database of Harold van der Heijden has the following study by Hugo Geiger of Munich from page 38 of the February 1920 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

When the solution was given on page 139 of the June 1920 issue it was remarked that the third promotion to a knight was not necessary, because 11 d8(Q) would win too:

The Geiger position was also discussed, without identification of him, in T.R. Dawson’s ‘Endings’ column on page 218 of the May 1938 BCM:

From page 262 of the June 1938 issue:

Dawson returned to the study on page 310 of the July 1938 BCM:

As regards the ‘fatal flaw’, the key point is whether the white king is on b1 or c1. The van der Heijden database has both versions, but who first proposed the improvement of placing the king on b1?

The position by L.A. Hulf which was mentioned by Dawson in the June 1938 BCM had appeared on page 299 of the 14 April 1938 CHESS, in Hulf’s ‘End Games’ column:

The solution was given on page 369 of the 14 June 1938 issue:

7419. Morphy novel (C.N. 5240)

Matt Fullerty’s novel about Paul Morphy, The Knight of New Orleans, has been published recently, a 556-page hardback. Its introductory pages describe Emanuel Lasker as ‘World Chess Champion for 27 years (1894-1918)’ and Louis Paulsen as ‘Swedish-American’; in rapid succession there are also references to ‘Amserdam’ and ‘aritocrats’ and a misattribution to ‘Grandmaster [sic] Rudolph [sic] Spielmann’ of the book/magician/machine quote, which dates from the nineteenth century (see C.N. 4156). From an initial skim of the novel itself we noted off-puttingly frequent misspellings of French words and expressions, and the book has taken a low place in our reading pile.

7420. Faulkner and Morphy

Also added to the reading pile is Faulkner’s Gambit

(subtitle: Chess and Literature) by Michael Wainwright

(New York, 2011). It ‘examines the chess structures,

motifs, and imagery in William Faulkner’s only novella,

situating this critically neglected work within both a

historical and literary context’. A central thesis is

that Faulkner’s character Gavin Stevens in Knight’s

Gambit was inspired by Paul Morphy.

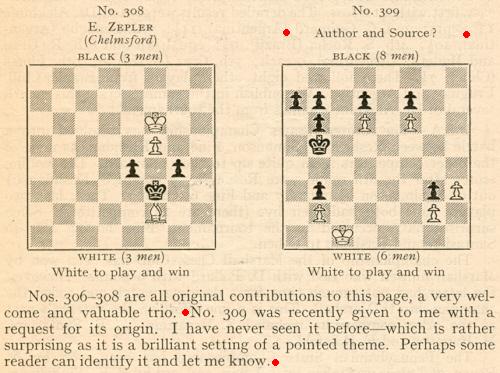

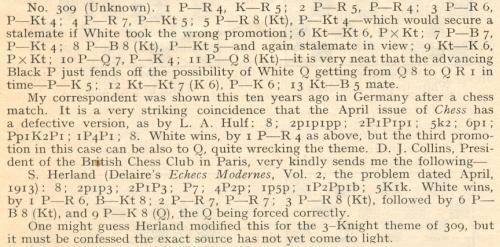

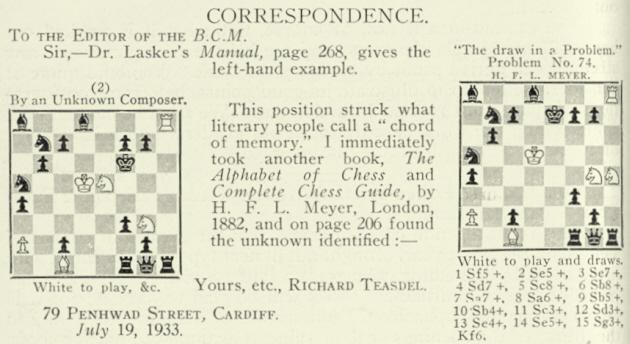

7421. ‘Unknown composer’

A letter from Richard Teasdel of Cardiff on page 342 of the August 1933 BCM:

7422. ‘Telemachus Brownsmith’

From page 145 of A Century of British Chess by Philip W. Sergeant (London, 1934):

‘The [Westminster] club rapidly grew to have a membership of two hundred; and in 1868 it was resolved to publish a magazine, The Westminster Chess Club Papers – to give it its full title at the start, which was shortened after the first year to The Westminster Papers. This was to be “a Monthly Journal of Chess, Whist, Games of Skill, and the Drama”, price sixpence, and appeared in April. Hewitt and Boden were at the beginning in general control, and Duffy was the chess editor; though on the cover of the third number there appeared the statement, in some archaic style of humour, “Edited by Telemachus Brownsmith”.’

Has any explanation for the particular pseudonym ever been offered?

7423. ‘Checkmate’ by M.B. Critchlow

The frontispiece of British Chess by Kenneth Matthews (London, 1948):

7424. Schiffers (C.N. 7416)

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) provides two quotes from the Deutsche Schachzeitung. Firstly, from the November 1899 issue, page 349 (with a reference to the third occurrence of a nervous illness):

‘Aus St. Petersburg. Der Schachmeister E. Schiffers ist wiederum (zum dritten Mal) von einer schweren Nervenkrankheit befallen, so dass sich eine Überführung in eine Heilanstalt als nothwendig erwiesen hat.’

Secondly, from the September 1900 issue, page 285 (a report on Schiffers’ recovery):

‘Aus St. Petersburg. E. Schiffers ist erfreulicherweise von seiner Nervenkrankheit wieder vollkommen hergestellt.’

Our correspondent adds that Schiffers’ obituary on pages 28-29 of the January 1905 Deutsche Schachzeitung made no mention of his illness, whereas pages 56-57 of the February 1905 BCM quoted a lengthy tribute in the St Petersburg Zeitung of 17 December 1904 which included the following:

‘The news of the death of the great Russian chess master came upon us with no surprise. Early in the spring, E. Schiffers injured himself by a fall; he was never entirely able to overcome its effects, and on 29 November (12 December) death put an end to his sufferings.’

‘In later years a deep melancholy impaired his mental elasticity, and he felt then the disfavour of Caissa. He became a man of solitude, and the cares of life weighed heavy on him.’

For the German text, which was written by Hans Seyboth, see pages 464-465 of the 25 December 1904 issue of Deutsches Wochenschach.

Below is a tribute to Schiffers (with an incorrect year for his death) from pages 74-75 of the Chess Budget, 12 December 1925:

7425. G.H. Diggle on B.H. Wood

There follow two articles by the Badmaster, originally published in Newsflash and reproduced on, respectively, page 111 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984) and pages 26-27 of volume two of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1987).

March 1984:

‘From his small corner in Newsflash the BM wishes to add (to those from more eminent voices) his congratulations to the Editor of CHESS on his recent award [the OBE]. This could not have come at a more fitting time, as shortly he will have completed 50 years’ continuous Editorship of his Magazine, certainly a record for this country, and possibly only equalled abroad by Hermann Helms (1870–1963), the late famous Editor of the American Chess Bulletin. Many British Editors of the past, through narrower and far less hectic periods, have handled their news adequately, skilfully assessing and supplying what their readers wanted; but the Chess World was rotating more slowly then, and the “forthcoming events” (Hastings, Margate or Scarborough, British Championship, etc.) came round at leisurely intervals like Easter, August holidays and Christmas. But no previous British Editor has stayed at the helm for virtually half a century – and a half century beginning with a great War which dried up all chess organization, followed afterwards by a monsoon of a revival and a flood of new events, and ending, after the further stimulus of a famous World Championship Match in 1972 (brilliantly covered at Reykjavik for CHESS by the Editor himself), with a vast chess population explosion and a chess calendar undreamt of in former days. 1939-45 was a hand-to-mouth struggle for all periodicals – paper rationing was one grim aspect, and in July 1943 Wood had to announce, under the heading “CHESS Torpedoed”, that at least 350 copies sent to America “had ended up at the bottom of the Atlantic” and appealed to home readers as an act of kindness “to spare their copies and return them for despatch as free replacements” – a much less strange request then than it sounds now.

The BM well remembers when CHESS was first launched upon an “Establishment” and a public rather set in their ways. The new Editor had “ideas”, and was at times an outspoken critic of (“Est-il possible?”) the British Chess Federation. There was much muttering by Metropolitan Methuselahs about “that fellow Wood”, and to have entered the sacred portals of the City of London Club brandishing the latest colourful copy of CHESS would have been like walking into White’s or Boodle’s in St James’s Street wearing a red tie. But after five decades the “enfant terrible” has now become an Elder Statesman himself, and though he allows generous space in his pages for healthy controversy he lets others do the fighting, confining himself to a few kindly ringside comments (in brackets) at the end of each “contest”. In some respects, he challenges comparison with the great Howard Staunton – both fearless writers, both tremendous workers and organisers, sometimes against heavy odds and periodical ill-health – but there is one vital difference. Staunton in his later years became obsessed with the past and obstinately refused to keep up with the times; Wood has throughout swum joyfully along with them.’

September 1985:

‘This month marks the completion of CHESS volume 50, and of B.H. Wood’s unbroken editorship. A sketch of the Magazine in War and Peace appeared in “Badmaster” for March 1984, but the Editor’s many and varied services to chess have rather obscured his playing career, which spanned from Worcester, 1931 (BCF Major Open Reserves) to Aberystwyth (British Championship) 30 years after, with only occasional appearances later. There was indeed one striking “afterglow” (Hastings “Challengers”, 1963). Forty applications had been received and the strongest ten selected; but there was a last-minute defection and Wood, aged 53 and out of practice, was “press-ganged” into playing. To his own astonishment he ended equal first with Brinck-Claussen (Denmark) and A.R.B. Thomas.

As a Tournament player he has been subject to as many vicissitudes as an Editor, but one remarkable and consistent feature of his pre-War play in his younger days (whether he did well or badly) was the almost total absence of drawn games. Both at the Yarmouth, 1935 and Nottingham, 1936 Major Opens he came seventh with identical scores (+5 –6 =0); previously at Hastings (Major D, 1933-34) he was first (+6 –2 =1) and again in 1934-35 equal first (Major B) with J.J. Doyle (+7 –1 =1).

In the British Championship itself (12 competitors) he was equal sixth (Bournemouth, 1936) with a score of +4 –4 =3, and equal tenth (Harrogate, 1947), where he scored +3 –6 =2. Then came what in the opinion of H.G. (Encyclopedia, 1977) was his “finest hour” – the British Championship, 1948. He opened by defeating William Winter in 24 moves (the first game to finish), in the second round he beat R.H. Newman (the ex-Army Champion), who tried to win a drawn game, with the usual result, in the third he won against Ritson Morry by some fine and exact endgame play, and in the fourth against his formidable namesake, G. Wood; an excellent pen and ink sketch by B. Feig of the two “Woodshifters” playing this game is to be found in the BCM, 1948, page 346. Far from running out of steam at this point, Wood went on to beat Alexander in 56 moves, making a clean score so far of five wins. In the sixth round he encountered the wily “H.G.” and lost a pawn early on, but fought back tenaciously and drew a rook and pawn ending after 76 moves. He then out-combined Dr Aitken, and his score stood at six and a half, still without a loss. But next he had to meet that notorious wrecker of score leaders, Gerald Abrahams, who up to now had had a wretched tournament, with one draw and six losses, but was always at his most deadly when seemingly prostrate. A tremendous battle ensued, and Wood went down on the 70th move. Nothing daunted, he then held Sir George Thomas to a draw after again being a pawn down in a rook and pawn ending, only to lose in the next round to Milner-Barry after sealing at the second adjournment a decisive mistake in a difficult ending when subsequent analysis showed he had a win. Of his ten games just played, three had taken over 70 moves and only two under 50. His score was now seven, and he would have led the field but for the one man he was due to meet in the final round – the redoubtable R.J. Broadbent (score: seven and a half).

Wood, though Black, played for a win. By vigorous tactics he broke through on the king’s side and had a won game on the 27th move; but through sheer stress and excitement he rejected winning the exchange (and the Championship) for “a quicker way”– with a flaw in it, and thus ended equal second in the august company of Sir George, “H.G.” and Milner-Barry. Next year the “Swiss System” was introduced, but 1948 was indeed a worthy finale to the old “all-play-all” regime. And though Wood was destined never to win the Championship, he was British Correspondence Champion for 1944/45. One of his best correspondence games (v Wallis) is given in Reinfeld’s British Chess Masterpieces (published in 1950).’

Below is the sketch of G. Wood and B.H. Wood referred to in the second article.

7426. Amsterdam v London

In the nineteenth century, games were seldom annotated at length, but an exception occurred in 1853, in the opening number of the British Chess Review: pages 22-28 discussed a correspondence game between Amsterdam and London, with notes by Greenaway and Medley.

Amsterdam – LondonCorrespondence, July 1851-November 1852

Scotch Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Bc5 5 c3 Nf6 6 e5 d5 7 Bb5 Ne4 8 cxd4 Bb6 9 Bxc6+ bxc6 10 Nc3 f5 11 h4 O-O 12 Bf4 c5 13 Kf1 Rb8 14 Na4 cxd4 15 Nxd4 Qe8 16 b3 c5 17 Nc2 d4 18 Rc1 Ba6+ 19 Kg1 Bb5 20 Na3 Bxa4 21 bxa4 Bc7 22 f3 Nc3 23 Qc2 Bxe5 24 Re1

24...Bxf4 25 Rxe8 Rfxe8 26 Kf2 Re2+ 27 Qxe2 Nxe2 28 Kxe2 Re8+ 29 Kf2 d3 30 Rd1 d2 31 Kf1 Bg3 32 Nc2 Re1+ 33 Rxe1 dxe1(Q)+ 34 Nxe1 Bxe1 35 Kxe1 Kf7 36 White resigns.

Page 28 of the British Chess Review commented that it was ‘perhaps the most brilliant game on record, ever played by correspondence’. In contrast, when the magazine’s editor, Daniel Harrwitz, gave the game on page 133 of his Lehrbuch des Schachspiels (Berlin, 1862) there was a single two-word note – ‘nicht gut’ – to a move (9 Bxc6+) which had received no comment in the British Chess Review.

See too pages 49-51 of volume one of Correspondence Chess Matches Between Clubs 1823-1899 by Carlo Alberto Pagni (Turin, 1994) and pages 44-46 of Correspondence Chess in Britain and Ireland, 1824-1987 by Tim Harding (Jefferson, 2011).

7427. More plagiarism

C.N. 6919 mentioned the work of fiction Paul Morphy: Confederate Spy by Stan Vaughan (Milwaukee, 2010). Now Rick Kennedy (Columbus, OH, USA) informs us that, as related on his webpage, he has noted cases of plagiarism. For example, page 63 has the following:

‘... an undigested cube of rock, and whoever designed it failed to realize that when plumbed down beside the delicate Moorish palaces upon which it encroached, it could only look ridiculous.’

Mr Kennedy found the identical passage (except for ‘plumped’ and ‘encroaches’) on page 227 of Iberia by James A. Michener.

As a small test of our own we opened the Morphy book at random and found, on page 113, whole chunks of text lifted by S. Vaughan from the website Exploring Toledo.

[Addition on 2 August 2013: the above Toledo link is not currently working.]

7428. Simultaneous exhibition

A poser for readers comes from Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands): in this photograph taken in Szczawno-Zdrój in 1957 who is giving the simultaneous exhibition?

The picture is owned by Ina Orbaan and comes from the collection of her brother Constant (1918-90), who was a participant in the second Przepiórka Memorial Tournament held in Szczawno-Zdrój in 1957.

7429. Photographs published by Delaire

The second fascicule of Les échecs modernes by Henri Delaire, publication of which was announced on pages 167-168 of the June 1915 issue of his magazine, La Stratégie, has a number of scarce photographs, although they are under 2.5cm in width. Three examples:

Isidor Gunsberg

Harry Nelson Pillsbury

Emanuel Lasker

The Lasker picture is similar to a well-known shot:

Is it possible to find better copies of the photographs which were given in Les échecs modernes?

| First column | << previous | Archives [89] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.