Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [88] | next >> | Current column |

7341. Schulder games

Further to our discussion of ‘Boden’s Mate’, as seen in the 15-move brilliancy Schulder v Boden, below are some other games played by the mysterious Schulder:

Daniel Harrwitz – SchulderOccasion?

Dutch Defence

1 d4 f5 2 c4 d6 3 Nc3 e6 4 f4 Nf6 5 Nf3 Nbd7 6 e3 b6 7 Ng5 Qe7 8 Nb5 Kd8 9 Qf3 d5 10 b3 h6 11 Nh3 a6 12 Nc3 Bb7 13 Be2 c5 14 Nf2 cxd4 15 exd4 Kc7 16 cxd5 Nxd5 17 Nxd5+ Bxd5 18 Qc3+ Kb7 19 O-O g5 20 Nd3 Rc8 21 Qd2 g4 22 Ne5 Nxe5 23 fxe5 h5 24 Qd3 b5 25 a4 Be4 26 Qd2 b4 27 Bc4 h4 28 Qe2 Rc6 29 Be3 h3 30 g3 Qd7 31 a5 Be7 32 Ra4 Rhc8 33 Raa1 Bd5 34 Rfc1 Be4 35 Ra2 Qd8

36 Bxa6+ Rxa6 37 Qb5+ Rb6 38 Qxb6+ Qxb6 39 axb6 Rxc1+ 40 Bxc1 Kxb6 41 Kf2 Bd5 42 Bd2 Kb5 43 Rb2 Bd8 44 Ke2 Bb6 45 Be3 Bd8 46 Kd3 Be4+ 47 Kd2 Bd5 48 Rb1 Bb6 49 Kc1 f4 50 gxf4 g3 51 Rb2 g2 52 Kd2 Bd8 53 Ke2 Bh4 54 Bg1 Kc6 55 Ke3 Be1 56 Ra2 Bxb3 57 Ra6+ Kb5 58 Ra8 Bc2

59 d5 exd5 60 e6 Bh4 61 Kd4 b3 62 Kxd5 Kb4 63 Rb8+ Kc3 64 Ke5 Kd2 65 f5 Ke2 66 f6 Kf1 67 Bd4

67...Bg3+ 68 hxg3 h2 69 f7 g1(Q) 70 f8(Q)+ Ke2 71 Qf4 Qg2 72 Qe3+ Kd1 73 Rd8 Resigns.

Source: Chess Player, October 1852, pages 50-51, with a correction on page 143 regarding White’s identity.

Schulder – Daniel HarrwitzOccasion?

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 c4 e6 3 b3 Nc6 4 Bb2 d6 5 g3 Nd4 6 Bg2 Ne7 7 Na3 g6 8 Nc2 Bg7 9 Nxd4 cxd4 10 d3 f5 11 exf5 Nxf5 12 Qe2 Qa5+ 13 Kd1 O-O 14 h4 Bh6 15 g4 Ne7 16 Bxd4 e5 17 Be3

17...Bxg4 18 Qxg4 Bxe3 19 fxe3 Qc3 20 Rc1 Qxd3+ 21 Ke1 Qxe3+ 22 Ne2 Qf2+ 23 Kd1 Nf5 24 Kd2 Qe3+ 25 Kc2 Qb6 26 Bd5+ Kh8 27 Kb1 Ne3 28 Qe4 Rf2 29 c5 Qb5 30 Qxe3 Rxe2 31 Qf3 Rf2 32 Qxf2 Qd3+ 33 Ka1 Qxd5 34 Qf6+ Kg8 35 Rhd1 Qe4 36 cxd6 Rf8 37 Qe6+ Kh8 38 d7 Qxh4 39 Rc8 Rd8 40 Rxd8+ Resigns.

Source: Chess Player, 1852, page 62.

Bernhard Horwitz – SchulderOccasion?

Queen’s Gambit Accepted

1 d4 d5 2 c4 dxc4 3 e4 e5 4 d5 f5 5 Nc3 Nf6 6 Bg5 Bd6 7 Bxc4 O-O 8 Nf3 h6 9 Bxf6 Qxf6 10 Qe2 a6 11 a3 b5 12 Ba2 b4 13 axb4 Bxb4 14 O-O Bd6 15 Rae1 f4 16 Bc4 a5 17 h3 Nd7 18 Nh2 Nc5 19 Qh5 Kh7 20 Ng4 Bxg4 21 hxg4 g6 22 Qh3 Rab8 23 Re2 Rb4 24 Ba2 f3 25 gxf3 Nd3 26 Rd2 Nf4 27 Qg3 h5 28 Ne2 h4 29 Qh2 g5 30 Nxf4 exf4 31 Rc1 Rxb2

32 Bb1 Kg7 33 Rdd1 Rfb8 34 Kg2 a4 35 Qg1 a3 36 Qe1 a2 37 Bd3 Qd4 38 e5 h3+ 39 Kh1 Qxd5 40 Be4 Qxe5 41 Rd5 Qe7 42 Qc3+ Kg8 43 Qc4 Kh8 44 Ra1 Rb1+ 45 Rd1 Rxa1 46 Rxa1 Rb1+ 47 Bxb1 Qe1+ 48 Kh2 Qxf2+ 49 Kxh3 Qg3 mate.

Source: Chess Player, 1852, pages 63-64.

Bernhard Horwitz – SchulderOccasion?

Falkbeer Counter-Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 f4 d5 3 exd5 exf4 4 Nf3 Bd6 5 Bb5+ c6 6 dxc6 bxc6 7 Bc4 Nf6 8 O-O O-O 9 d4 Bg4 10 c3 Nbd7 11 b3 Ne4 12 Qc2 Ndf6 13 Bd3 Bxf3 14 Rxf3 Ng5 15 Rf1 Qc7 16 Na3 h6 17 Nc4 Nd5 18 Nxd6 Qxd6 19 Qf2 Ne6 20 Bd2 g5 21 Rfe1 Nf6 22 Re2 Kg7 23 Rae1 Rae8 24 h4 Nh5 25 Re5 f6 26 Ra5 Rf7 27 Bc4 Rfe7 28 Bxe6 Rxe6 29 Rxa7+ Kg6 30 Rxe6 Qxe6 31 c4 Ng3 32 Bb4 Qe4 33 Kh2 Qb1 34 h5+ Kf5 35 Ra5+ Kg4 36 Qf3+ Kh4 37 White resigns.

Source: Chess Player, 1852, pages 73-74.

Schulder – SimonsOccasion?

Philidor’s Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 c6 5 O-O d5 6 exd5 cxd5 7 Bb3 Nf6 8 Qxd4 Nc6 9 Ba4 Be7 10 Ne5 Bd7 11 Nxc6 bxc6 12 Bg5 O-O 13 Nc3 Rb8 14 Rae1 Rb4 15 Qxa7 Rg4 16 f4 h6

17 h3 hxg5 18 hxg4 Nxg4 19 Bxc6 gxf4 20 Bxd7 Ne3 21 Rxf4 Bg5 22 Rf3 Nxc2 23 Re2 d4 24 Rxc2 dxc3 25 Rcxc3 Qe7 26 Rcd3 Rc8 27 Rf1 Rd8 28 Rfd1 Bf4 29 Qf2 Qg5 30 g3 Rxd7 31 Qxf4 and wins.

Source: Chess Player, 1852-53, page 87.

Mr P. (‘one of the finest players of the day’) – SchulderOccasion?

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 e6 2 f4 c5 3 Nf3 b6 4 d3 Bb7 5 Be2 d5 6 e5 Nh6 7 Be3 Ng4 8 Bg1 Nh6 9 Bf2 Nc6 10 O-O Be7 11 Nbd2 Rc8 12 d4 a6 13 c3 Nf5 14 Bd3 Nh6 15 h3 cxd4 16 Nxd4 Nxd4 17 Bxd4 f5 18 exf6 Bxf6 19 Qh5+ Nf7 20 Rae1 Bxd4+ 21 cxd4 Qf6 22 Nf3 g6 23 Qg4 Rc6

24 f5 gxf5 25 Bxf5 Ke7 26 Bxe6 Nh6 27 Bxd5+ Kd8 28 Qh5 Rc7 29 Re6 Qf4 30 Bxb7 Nf5 31 Re4 Ng3 32 Qd5+ Rd7 33 Qxd7+ Kxd7 34 Ne5+ Kc7 35 Rfxf4 Resigns.

Source: Chess Player, 1852-53, pages 105-106.

Frank Healey – SchulderPhilidorian Chess Rooms, London, 3 June 1859

Bishop’s Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Qe7 3 Nc3 c6 4 Nge2 d6 5 O-O Be6 6 Bb3 g6 7 d4 Bxb3 8 axb3 Nd7 9 f4 Bg7 10 d5 f6 11 f5 gxf5 12 Rxf5 Nh6

13 Ng3 Nxf5 14 Nxf5 Qf8 15 dxc6 bxc6 16 Nxd6+ Kd8 17 Be3 Kc7 18 Nf5 h5 19 Ra6 Rh7 20 Rxc6+ Kxc6 21 Qd5+ Kc7 22 Nb5+ Resigns.

Source: Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1859, pages 208-209.

Schulder – Frank HealeyPhilidorian Chess Rooms, London, 3 June 1859

King Pawn’s Opening

1 e4 e5 2 g3 f5 3 d4 exd4 4 Bg2 Nc6 5 Ne2 fxe4 6 Bxe4 Bc5 7 Bd5 Nf6 8 c4 Nb4 9 Nf4 Nbxd5 10 Nxd5 O-O 11 O-O Nxd5 12 cxd5 d6 13 b4 Bxb4 14 Qxd4 Bc5 15 Qc3 Bh3 16 Bb2 Qe7 17 Nd2 Rf7 18 Rae1

18...Rxf2 19 Rxf2 Qxe1+ 20 Nf1 Qxf1 mate.

Source: Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1859, pages 209-210.

Finally, we note on pages 316-317 of the British Chess Review, 1853 a comment about White’s fourth move in the first game of that year’s match between Löwenthal and Harrwitz, which began 1 e4 e5 2 f4 Bc5 3 Nf3 d6 4 b4:

‘This move, we are informed, is the invention of Mr Schulder, a strong German amateur, with whom this opening is a great favourite.’

7342. Recommended booksellers (C.N.s 4737, 6147 & 6659)

A new catalogue has just been produced by Tony Peterson of Southend-on-Sea, England.

7343. Capablanca and Ed Hughes (C.N. 7337)

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) draws attention to an article ‘Capablanca’s Brain Would Not Do in Sports’ on page 1 of the Sporting Section of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 5 March 1922.

7344. Wade v Bennett (C.N. 7270)

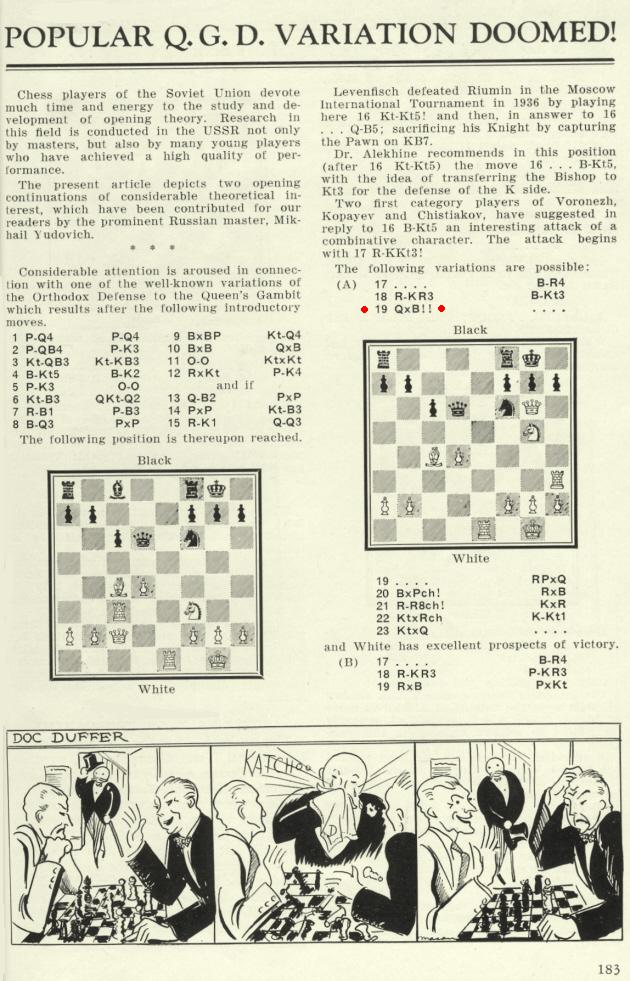

Regarding the Wade v Bennett correspondence game (1942) and the prior appearance of 19 Qxg6 in analysis, below is an article on pages 183-184 of the September 1939 Chess Review:

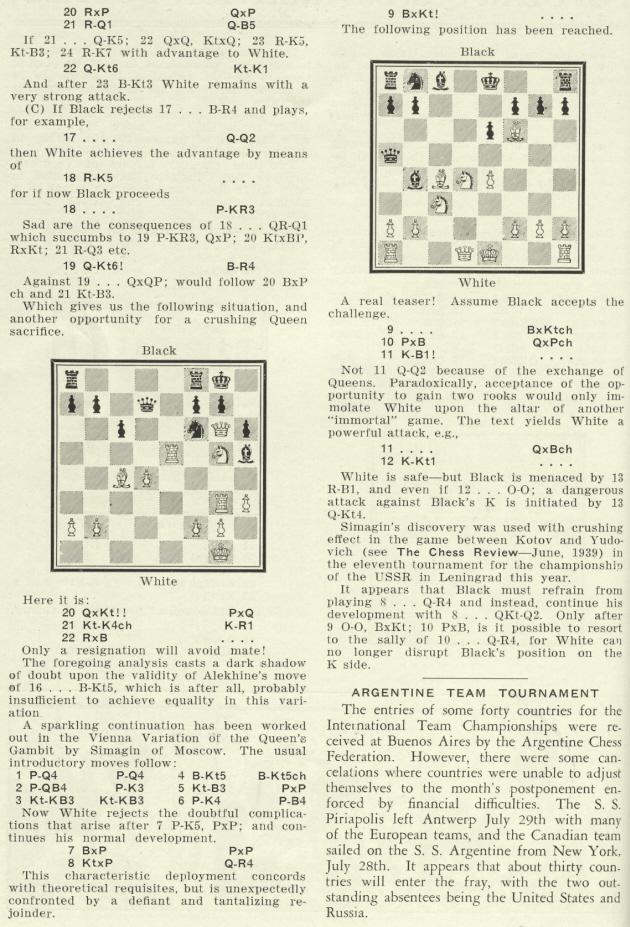

7345. Bobby Fischer Against the World

Graced with some exceptionally rich archive material, Liz Garbus’s 2011 documentary film Bobby Fischer Against the World is disgraced with some exceptionally poor interviewees. A particular low point, with some of the talking heads less concerned about being truthful than noticed, is the dense sequence which seizes on the issue of insanity:

Anthony Saidy: ‘Victor Korchnoi claimed to have played a match with a dead man and he even provided the moves.’

Asa Hoffmann: ‘Rubinstein jumped out of the window because the fly was after him.’

Anthony Saidy: ‘Steinitz in late life thought he was playing chess by wireless with God Almighty – and had the better of God Almighty.’

Asa Hoffmann: ‘Carlos Torre took all his clothes off on a bus.’

To highlight only the Steinitz versus God yarn, no scrap of serious substantiation is available. Once again we witness the magnetic pull of malignant anecdotitis. And since the theme is insanity, an uncomfortable question arises: can such groundless public denigration of Steinitz and others be considered the conduct of a rational human being?

7346. Fine’s office

Horacio Paletta (Buenos Aires) notes a news item on page 36 of the February 1949 Chess Review:

‘Dr Reuben Fine, a clinical psychologist, announces that he has opened an office at 72 Barrow Street, New York City (REpublic 9-8054). He is available for personality diagnosis and psychotherapy.’

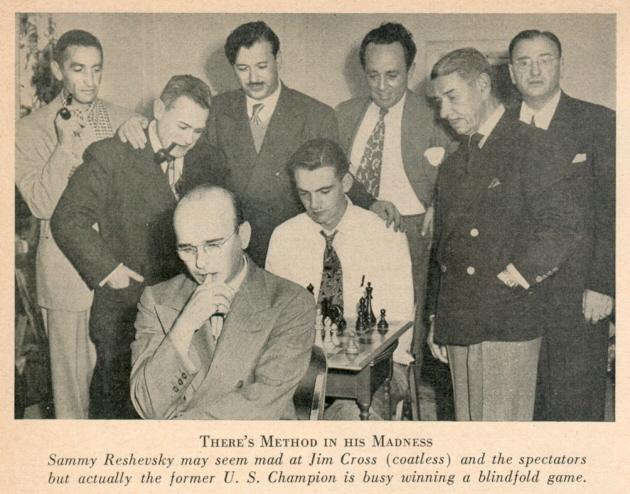

7347. Reshevsky playing blindfold

Mr Paletta adds that this photograph appeared on the same page of Chess Review:

7348. Reshevsky and Point Count

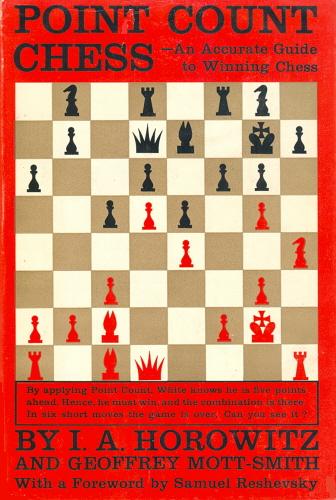

Chess

‘When I was a child prodigy many years ago, chessplayers were amazed at the ease and accuracy of my play against the veritable giants of chessdom. To be perfectly frank, I was no less amazed, and I have thought about this over and over again. What was it that I had which has been variously described as talent or genius or the divine afflatus which enabled me to select the proper move or line in a given situation? The answer to this question, of course, should prove enlightening. I discovered that I had the happy faculty of being able to spot weak and strong points in a position merely by a glance at its contour. Having done so, I could go on to the next step and enhance my strong points, while surveying my weak ones and/or contain my opponent’s strong points and exploit his weak ones.

I fear that I cannot account for this fortuitous bounty. I do know, however, that the foundation of chess logic is the perception of weak and strong points on the board or projected a few moves from possibility to reality. Point Count Chess exactly coincides with my reflections on this matter. Not only does it define the salient features, but also it evaluates them. It is unique in the annals of chess literature in that it is the first and only book that does so. Indeed, it is a great stride forward in bringing the essential ideas to the ordinary player.’

The above is Samuel Reshevsky’s Foreword to Point Count Chess by I.A. Horowitz and Geoffrey Mott-Smith (New York, 1960).

The diagram position comes from the game I.A. Horowitz v A. Martin, Boston, 1938. Reinfeld’s annotations were published on pages 183-184 of the August 1938 Chess Review and on pages 25-26 of volume four of the Year Book of the American Chess Federation (Milwaukee, 1939). From page iv of the latter publication comes this photograph of Horowitz:

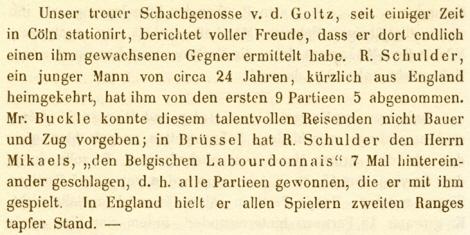

7349. Schulder games (C.N. 7341)

Gene Gnandt (Houston, TX, USA) draws attention to an item about Schulder on page 300 of the August 1849 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

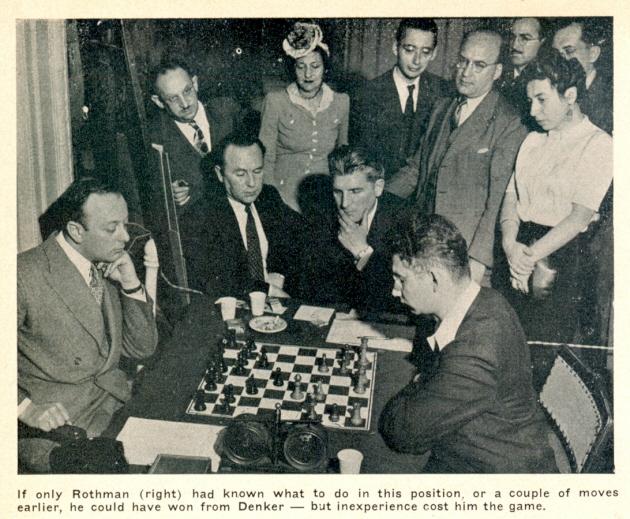

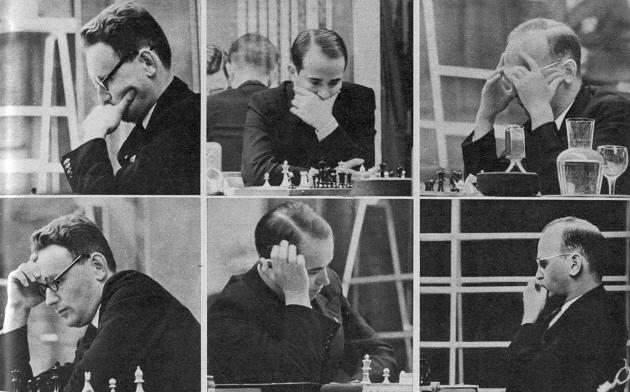

7350. A. Rothman (C.N. 4930)

We are still seeking biographical information about A. Rothman, who claimed to know the entirety of Modern Chess Openings by heart.

Below is a photograph on page 10 of the May 1944 Chess

Review, in a report on the US championship in New

York:

7351. Chicago, 1937

Source: the frontispiece to volume three of the Year Book of the American Chess Federation (Milwaukee, 1938).

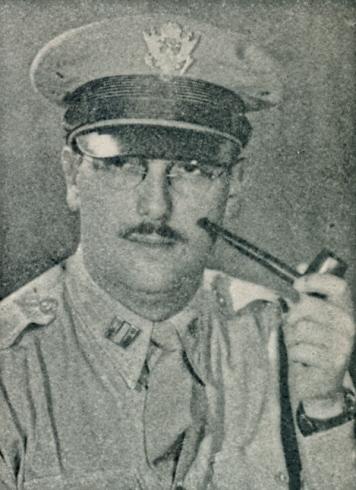

7352. Who?

The only clue being offered: a writer on chess history.

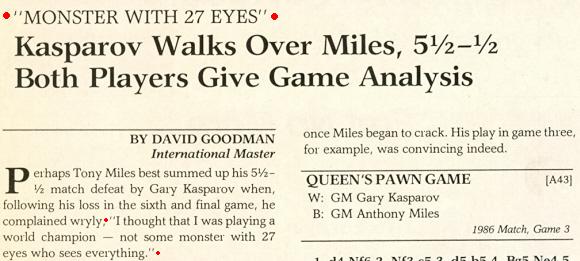

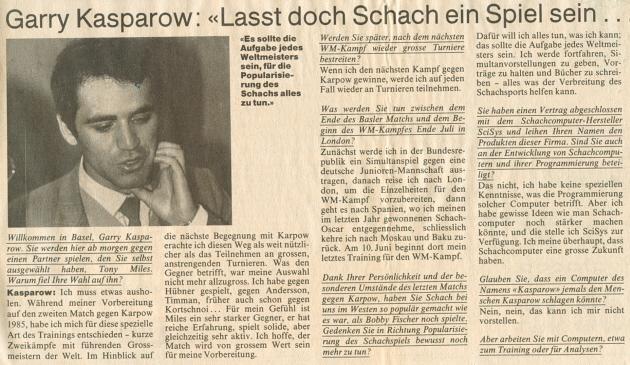

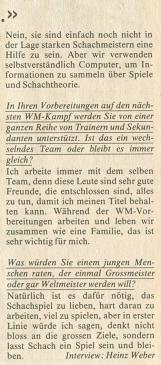

7353. Miles on Kasparov

From page 12 of the August 1986 Chess Life:

But why 27 eyes or, for that matter, 28,000 eyes (in another version of the Miles quote to be found on web pages)?

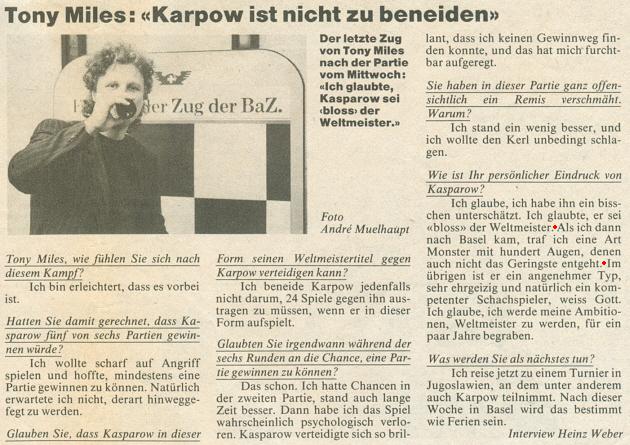

The Kasparov v Miles match took place in Basle in May 1986, and we have found Miles’ jocular/ocular remark (‘100 eyes’) in a post-match interview with Heinz Weber on page 3 of the Basler Zeitung, 23 May 1986:

Kasparov gave the figure 100 on page 188 of Child of Change (London, 1987) and page 193 of Unlimited Challenge (Glasgow, 1990).

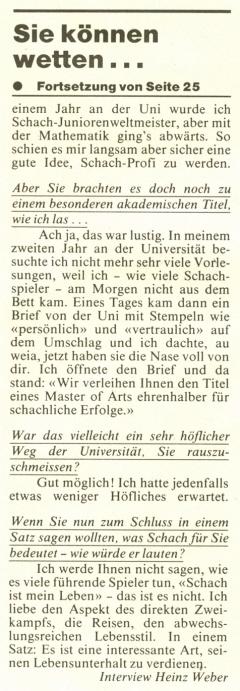

Earlier, the Basler Zeitung had published interviews with both players, and the full texts are reproduced here:

Above: Basler Zeitung, 13 May 1986, pages 25 and 27

Above: Basler Zeitung, 15 May 1986, page 35

Above: Basler Zeitung, 15 May 1986, page 35.

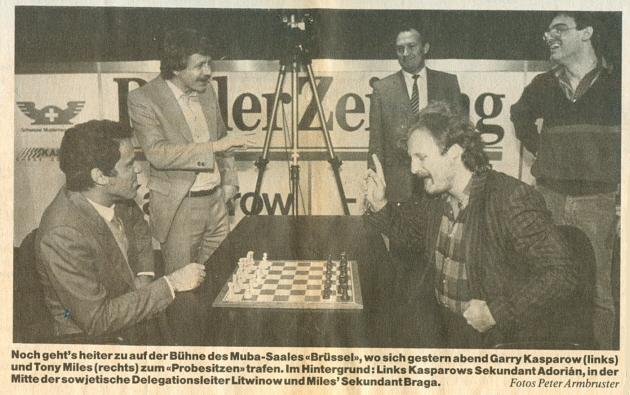

7354. Hastings, 1895 group photograph (C.N.s 4663, 5832, 5836 & 5841)

Raymond Kuzanek (Hickory Hills, IL, USA) has found the photograph on page 221 of The Sketch, 21 August 1895:

Is it possible to obtain a copy in a higher resolution?

7355. Mark Taimanov’s chess library

Mark Taimanov (Moscow) informs us that he plans to dispose of his chess library and is seeking a buyer.

The collection consists of over 500 books plus 120 complete volumes of periodicals. To mention only some of the categories, there are nearly 80 books on the openings, almost 60 on the middle-game and 14 on endings. Other categories include tournament and match books, biographical games collections, endgame studies, year books and memoirs. Most of the works are in Russian, but there are also volumes in English, French, German, Spanish, Hungarian, Czech, Serbian, Finnish and Estonian. A number of books are inscribed by their authors.

Any readers interested in acquiring this unique collection are invited to let us know as soon as possible, and we shall forward their contact details to Mr Taimanov.

Below, from our archives, is a photograph taken during the 1953 Candidates’ tournament in Neuhausen and Zurich:

Mark Taimanov and Salo Flohr

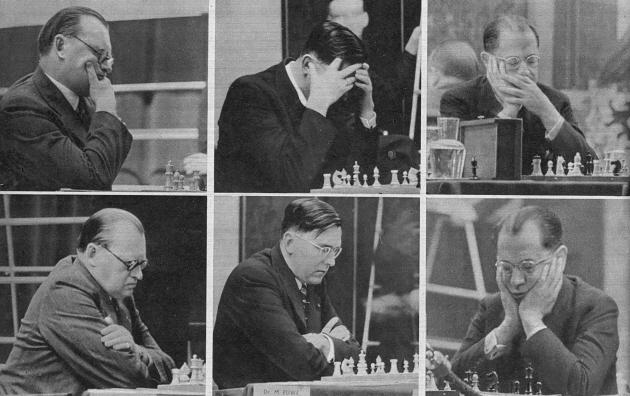

7356. AVRO, 1938

photographs (C.N.s 6640 & 7191)

Pages 57-59 of Picture Post, 26 November 1938 had a richly illustrated article on that year’s AVRO tournament. Below are all the photographs on pages 58-59. The first of them is 52 cm long in the magazine and has been split here into two:

M. Botvinnik, S. Reshevsky, R. Fine and S. Landau (‘for Capablanca’)

M. Euwe, A. Alekhine, S. Flohr and P. Keres

A. Alekhine, M. Euwe and J.R. Capablanca

M. Botvinnik, S. Flohr and S. Reshevsky.

No individual photographs of R. Fine and P. Keres were given.

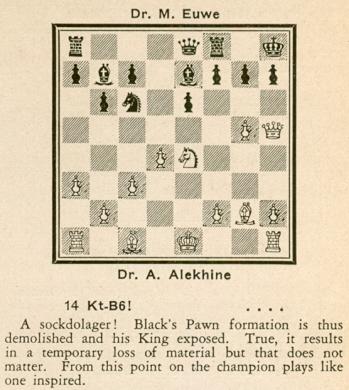

7357. A. Rothman (C.N.s 4930 &

7350)

Larry Crawford (Milford, CT, USA) and Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) note the following report regarding Aaron A. Rothman on page 33 of the New York Times, 20 December 1961:

7358. Pillsbury’s place of birth

As stated on, for instance, page 345 of the Hastings, 1895 tournament book, H.N. Pillsbury was born in Somerville, Massachusetts on 5 December 1872, yet even today there are occasional claims that he was born in South Carolina.

In some old sources, Somerville was misspelled Sommerville. See, for example, page 3 of Harry Nelson Pillsbury. 200 partier by W. Henrici (Stockholm, 1913) and, in particular, page 188 of Die Meister des Schachbretts by R. Réti (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1930). In the English edition of the latter book, Masters of the Chess Board (London, 1933), the incorrect ‘Sommerville’ became the incorrect ‘Summerville’ (see page 100), leaving the reader to assume that Summerville, South Carolina was meant.

The matter was raised, with a mention of Masters of the Chess Board, by L.F. Oakley in a letter published on page 2 of the April 1944 Chess Review. The Editor’s reply noted that W.E. Napier, Pillsbury’s brother-in-law, had confirmed that Somerville, Massachusetts was the correct place. Somerville was also stipulated on page 162 of the book discussed in C.N.s 4380 and 4397, The Pillsbury Family by David B. Pilsbury and Emily A. Getchell (Everett, 1898).

7359. Tarrasch translations

Bradley J. Willis (Edmonton, Canada) is interested in translations of Tarrasch’s books. Can readers assist us in building up a comprehensive list?

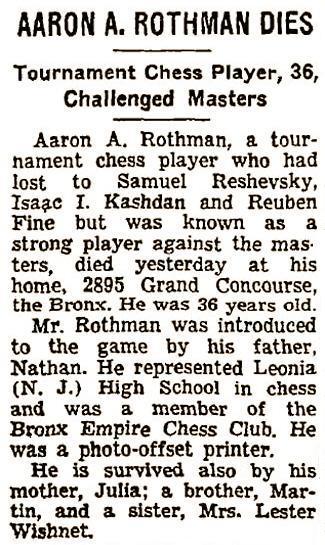

7360. The first sockdolager

Which was the first chess move to be described as a sockdolager or sockdologer? This US slang term, meaning ‘a heavy or knock-down blow’, is commonly linked to the name of Al Horowitz, and an early example comes in his notes to the seventh match-game in the 1935 world championship:

Source: Chess Review, January 1936, page 5.

There was a (non-chess) lexicographical explanation of the word on page 31 of the February 1928 American Chess Bulletin. On page 13 of the January 1930 issue ‘sockdologer’ appeared in a note by Charles De Vide (Devidé) to 51...g3 in the tenth game in the 1929 match for the Italian championship between Stefano Rosselli del Turco and Mario Monticelli:

‘The “sockdologer”. White must take, whereupon K-K5 destroys White’s last hope. Due credit should be given the victor for his consummate skill in handling the entire endgame.’

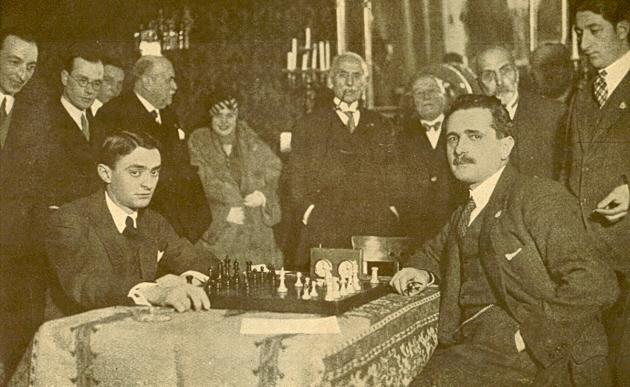

A photograph taken during the match, held in Florence, was published opposite page 200 of the May 1929 issue of L’Echiquier:

M. Monticelli and S. Rosselli del Turco

7361. Baloney

Regarding Bobby Fischer Against the World (C.N. 7345), Tony Bronzin (Newark, DE, USA) notes a remark by Anthony Saidy on the third game in the 1972 world championship match, which began 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 c5:

‘In game three Bobby played an opening, a defense, he had never played before, the Benoni ...’

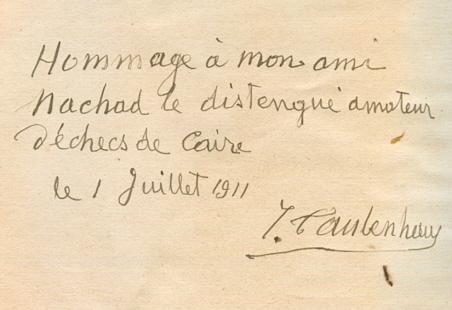

7362. Taubenhaus inscription

An inscription in one of our copies of Traité du jeu des échecs by Jean Taubenhaus (Paris, 1910):

7363. Morphy against the Devil

The story about Morphy against the Devil, in connection with a picture by Moritz Retzsch, is too familiar to be repeated here. See, for instance, pages 235 and 269 of Paul Morphy The Pride and Sorrow of Chess by David Lawson (New York, 1976), as well as the following non-exhaustive list of magazine items:

- Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1844 (volume five), pages 272-274;

- Le Palamède, September 1845, pages 397-400;

- Chess Monthly, April 1861, pages 126-127;

- Westminster Papers, 1 January 1873, page 132;

- Columbia Chess Chronicle, 18 August 1888, page 60, 8 September 1888, page 84, 22 September 1888, page 102, 29 December 1888, page 209, 3 January 1889, pages 3-5 and 24 January 1889, page 35;

- Deutsche Schachzeitung, October 1889, pages 316-318;

- American Chess Magazine, August 1898, page 77;

- Chess Amateur, July 1907, page 313;

- Chess Amateur, February 1920, page 146;

- BCM, November 1932, page 481;

- CHESS, 17 September 1938, page 8;

- BCM, April 1939, page 185;

- Chess World, July 1954, page 160;

- BCM, July 1987, page 315;

- BCM, August 1993, page 443 and September 1993, page 506.

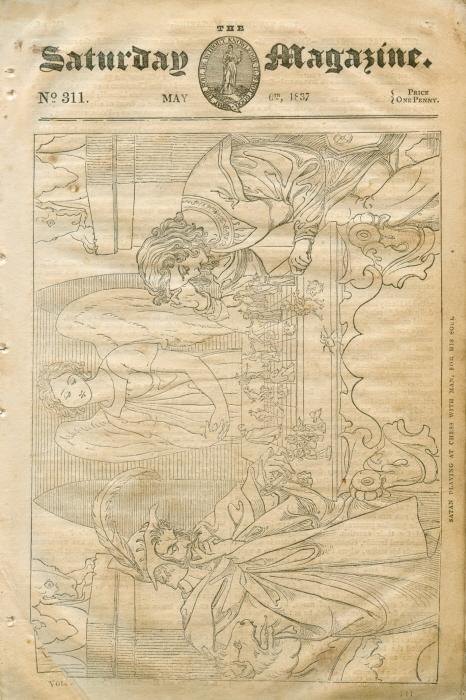

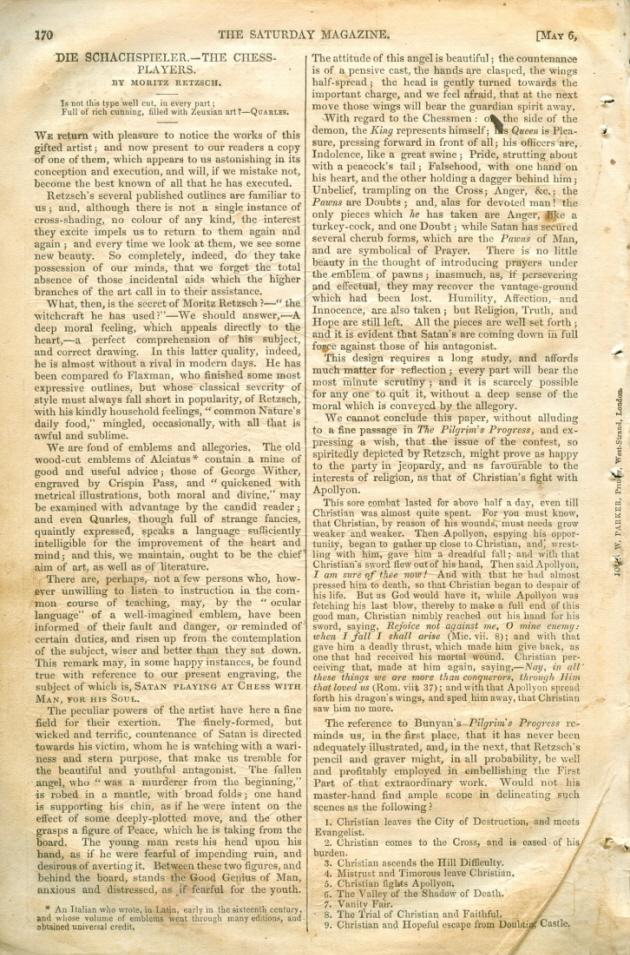

The oldest related item in our collection dates from the month before Morphy was born, i.e. The Saturday Magazine of 6 May 1837. Below are the front cover (page 169) and the text on page 170:

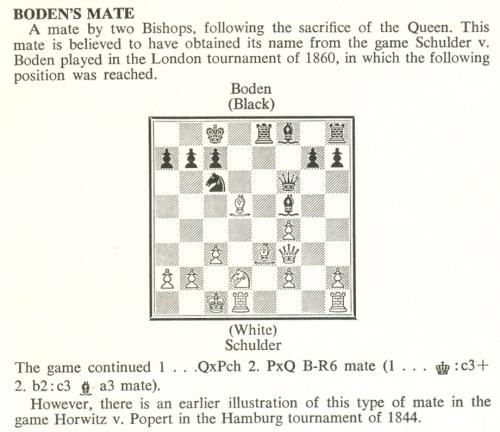

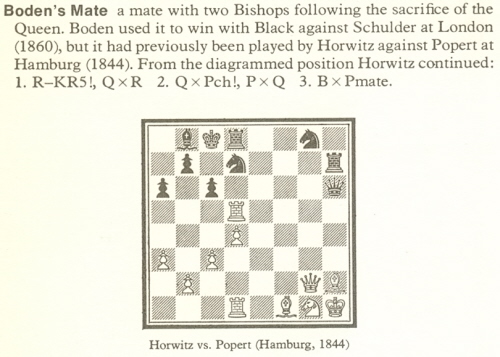

7364. Boden’s Mate (C.N. 7341)

As mentioned in our article on Boden’s Mate, C.N. 292 drew attention to the similar entries on page 35 of The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks (London, 1970) – as well as page 54 of the 1976 edition – and on page 40 of An illustrated Dictionary of Chess by Edward R. Brace (London, 1977):

Sunnucks

Brace

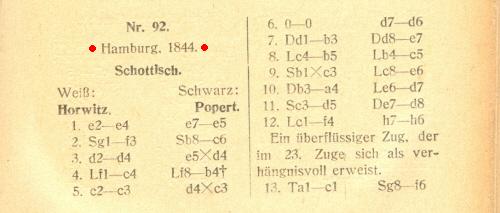

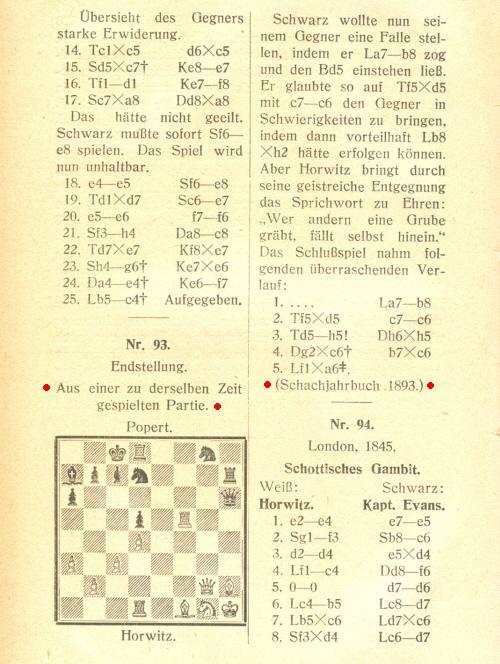

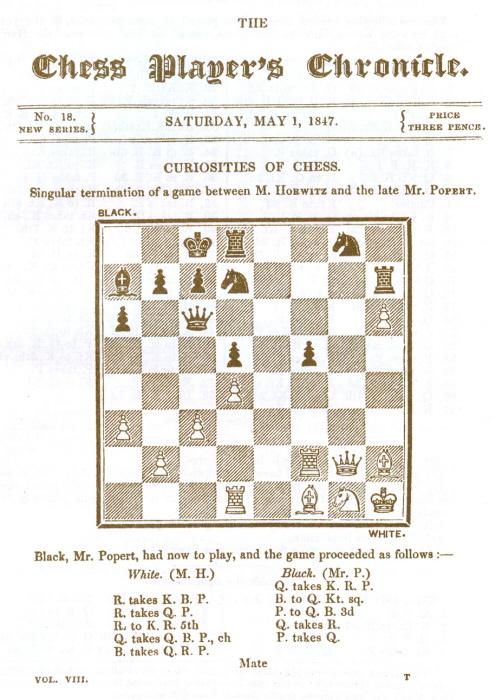

The Horwitz v Popert game was discussed by Richard Forster in his ‘Late Knight’ column at the Chess Café in September 2002, reference being made to pages 167-168 of volume two of Aus Vergangenen Zeiten by L. Bachmann (Berlin, 1920-22):

In his column the following month Richard Forster reported that a correspondent, Peter Anderberg, had found the position on page 108 of the Schachjahrbuch for 1894, not 1893. That source gave the occasion as Hamburg, 1844 and included two introductory moves:

1…Qxh6 2 Rxf5 Bb8 3 Rxd5 c6 4 Rh5 Qxh5 5 Qxc6+ bxc6 6 Bxa6 mate.

That position had been given, without any venue or date,

on page 137 of the 1 May 1847 issue of the Chess

Player’s Chronicle:

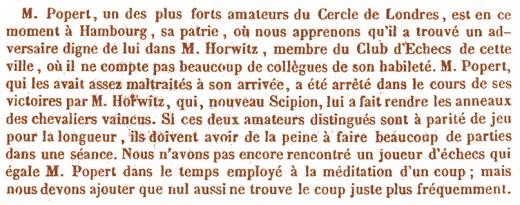

The reference to the ‘late Mr Popert’ will be noted. As regards his encounters with Horwitz, we reproduce a news item from page 234 of the 15 November 1842 issue of Le Palamède:

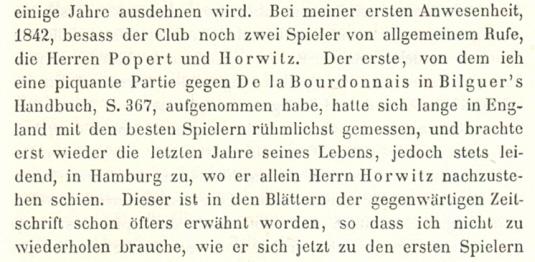

Finally, from pages 117-118 of the April 1847 Deutsche Schachzeitung (an article by von der Lasa entitled ‘Das Schachspiel in Hamburg und Altona’):

What more can be discovered about the Horwitz v Popert

game, which is purportedly the first occurrence of

‘Boden’s Mate’? In particular, what is best corroboration

available of the date 1844 and, of course, can the full

game-score be traced?

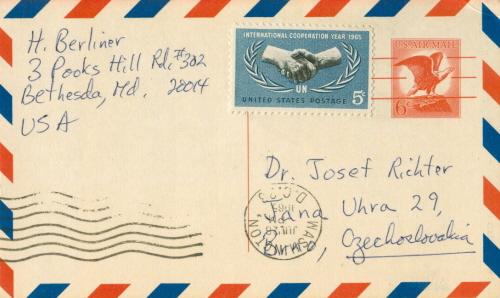

7365. Correspondence chess postcard

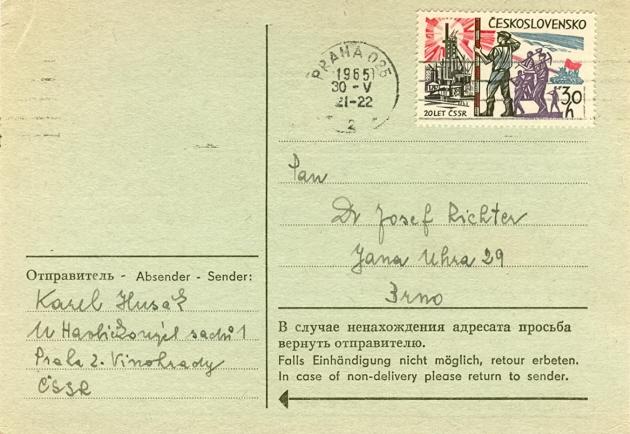

A postcard in our collection sent by Karel Husák to Josef Richter:

7366. More postcards to Josef Richter

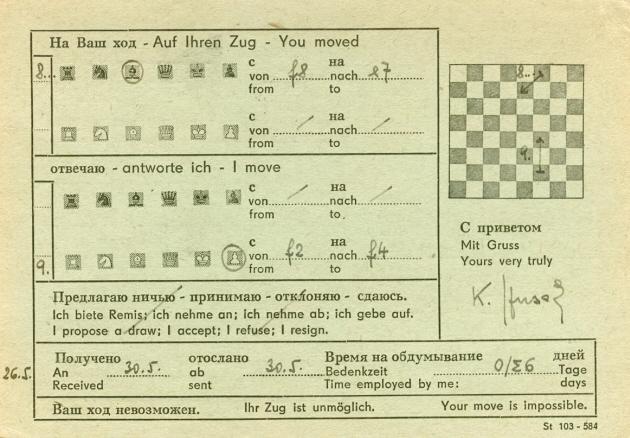

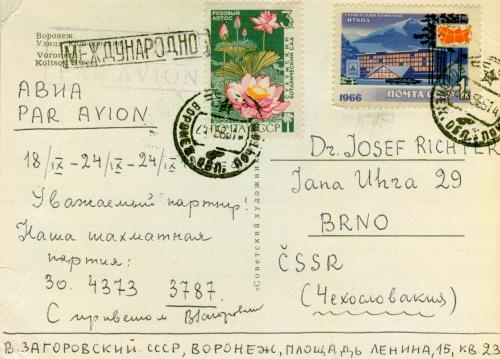

The postcard shown in the previous item concerned a game played in the Fifth World Correspondence Championship (1965-68), which was won by Hans Berliner. From the same event, here are two more cards sent to Josef Richter:

Zagorovsky plays 30...Rc7-h7.

Berliner plays 11...e7-e5.

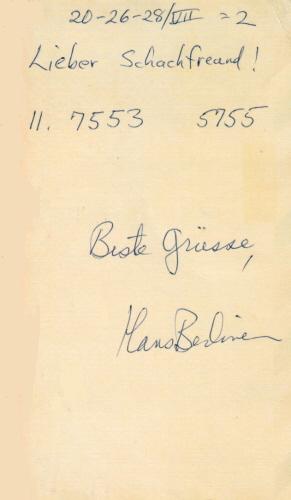

7367. Who? (C.N. 7352)

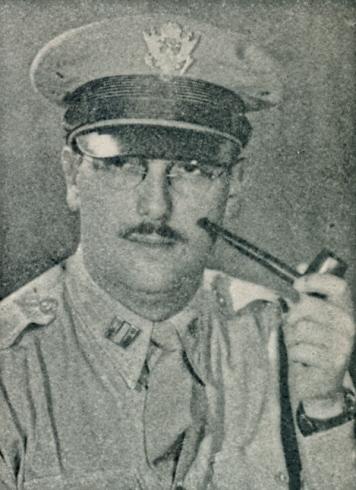

This photograph of Henry Alexander Davidson (1905-73) was on page 3 of the November 1944 Chess Review, accompanying his article ‘Can a Dope Become a Denker?’. He was referred to as ‘Capt. Henry A. Davidson, a psychiatrist now serving in a US Army Hospital in New Guinea – “a green inferno where the mildew rots the chessboards and the mould slimes up the chessmen”.’

Davidson was the author of A Short History of Chess (New York, 1949), whose dust-jacket had this biographical note:

7368. Popert (C.N. 7364)

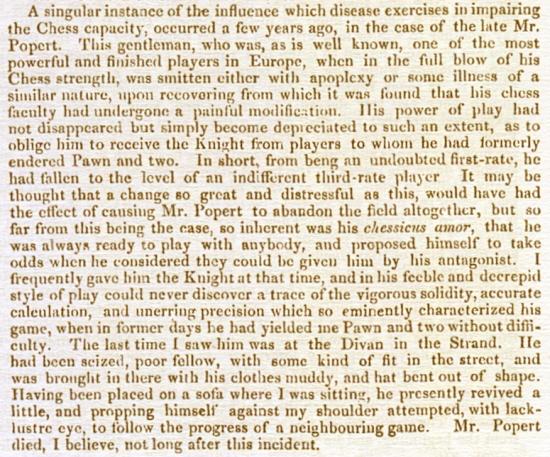

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) notes a passage

about Popert written by H.A. Kennedy in his article

‘Chess Chips’ on page 122 of the Chess Player’s

Chronicle, 1851 and, with some minor textual

differences, on pages 150-152 of Kennedy’s anthology Waifs

and Strays (London, 1862). Below is what appeared

in the Chronicle:

We note that according to page 143 of the May 1859 Chess Monthly, Popert died in 1846:

7369. La Bourdonnais v McDonnell

An article by G.H. Diggle on pages 277-281 of the July 1934 BCM marked the centenary of the La Bourdonnais v McDonnell matches; it was reprinted on pages 69-75 of The Treasury of Chess Lore by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1951). In Newsflash in June and July 1984 Diggle wrote a further feature on the matches. Given on pages 3-6 of volume two of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1987), the two parts are reproduced below.

June 1984:

‘This month marks the 150th Anniversary of a famous match series which (wrote R.N. Coles) “still bears comparison with that of any later age”, when, in the words of George Walker, “La Bourdonnais came to London with the roses of June” and encountered the great Irishman Alexander McDonnell in 85 games lasting all through the Summer (La B. 46, McD. 26, Drawn 13). These games were unevenly split between six matches, but the conditions of play were very loose – there were no seconds, there was no time-limit, the stakes were “very small” and, amazing to relate, the whole splendid series would never have been preserved for us but for one man. William Greenwood Walker, the aged Secretary of the Westminster Chess Club, was “little of a chessplayer” but a fanatical “fan” of McDonnell’s, and throughout the whole 85 games the old gentleman sat beside the English Champion “with spectacles on nose” eagerly taking down the moves and “scarce daring to breathe lest the conceptions of his hero should miscarry”. George Walker (not a relative) wrote of him: “He died full of years – we would well have spared a better – aye – many a better man.”

The Champions played every day of the week except Sunday, usually from noon till 6 or 7 p.m., but never more than one game at a sitting. Many games were adjourned till next day. Indeed, McDonnell was (except Williams) the slowest player this country ever produced. “I have seen him an hour and a half”, writes George Walker, “and even more, over a single move, and I once timed La Bourdonnais 55 minutes”. But in those spacious days this seems to have impressed rather than repelled the spectators, who (even if themselves not sufficiently advanced to appreciate the quality of the play) felt that “this was indeed chess”, far superior to such weasel encounters of the past as that in 1821 between Lewis and Deschapelles, who played their three games match “before dinner”.

The circumstances, as distinct from the conditions, under which the matches were played strongly favoured McDonnell. He was a very comfortably off bachelor who held the post of Secretary of the West India Committee of Merchants with a salary of £1,200 a year. As his duties were to watch the progress of Bills affecting the West Indies, he had work to do only when the Houses of Parliament were sitting (in fact, the Palace of Westminster was burnt down in the famous 1834 fire, which must have occurred during the match). La Bourdonnais, though of a noble family and heir to an old estate – in the earlier years of his marriage he possessed “un château, cinq domestiques, et deux équipages” – impetuously lost all his money in a building speculation and came down to £60 a year as Secretary of the Paris Chess Club and what he could make as a professional at the Café de la Régence. During the McDonnell matches his boisterous resilience was such that he would follow up a seven-hour struggle by playing for half-a-crown a game against all-comers till long after midnight.

McDonnell only lived a year after the great encounter, being stricken with Bright’s Disease at the age of 37. Later, in Le Palamède, La Bourdonnais wrote handsomely about him as the greatest player he had ever encountered (he did add, as a rather hurried afterthought, except M. Deschapelles, but this was a sop to his touchy old predecessor). No portrait of McDonnell has survived and the only one of La Bourdonnais (the frontispiece of Le Palamède, 1842) was described by Staunton (Chess Player’s Chronicle, volume two, page 159) as a “lithographic enormity”, though Staunton never actually saw either of the two masters.

As many varying opinions on the actual games have been expressed by experts, the BM (having just played through the whole series) hopes next month to report on his “findings”, which will no doubt stagger the Chess World and set everybody right.’

July 1984:

‘To play through the 85 La Bourdonnais-McDonnell games, covering just over 3,500 moves aside, is rather like crossing the Atlantic in stormy weather, or at best choppy seas with deceitful calms. And to annotate them, even for an expert, must be a nightmare. Staunton himself, who did so (Chess Player’s Chronicle, volumes 1-3), really sums up the series in a famous note to Game 21: “It seems utterly impossible for either player to save the game.” Such were the complications he encountered that even he, never afraid of deep analysis, was sometimes driven to dodge the “heavy seas” and pick on shallower water where he could say something when there was nothing to be said: “The youngest player will perceive that White would have lost his queen had he imprudently captured the queen’s pawn.”

Both masters were of the same temperament, daring in attack and ingenious in defence. McDonnell in particular could always start something out of nothing. And throughout the six matches both completely ignored the state of the score, playing each game solely to win, and even (there being no time-limit) to win like human computers by seeing every variation. Though in this they never succeeded, in some games, notably the 47th, they came magnificently close to it. During this great struggle, in which the middle-game “revels” begin as early as the ninth move with every piece still on the board, neither player misses anything throughout a colossal mêlée lasting up to the 20th, when the position seems to collapse under its own weight and the two queens and two minor pieces aside perish in the debris. But the survivors on both sides are on their feet again in an instant, and a new phase begins – an enthralling race between two rook-supported clusters of passed pawns, ending in a hair-raising French victory in 53 moves. While croaking “moderns” will condemn this game (“Wot? No logical Theme?” or “Wot? No planned connection between the first half and the second?”), the BM can only growl defiantly, “Let them croak!”

Of the 85 games, the following have been agreed by generations of critics to be “the greats”: games 17, 47, 62 and 78 won by the Frenchman and 5, 21, 30, 50 and 54 won by McDonnell. To these the BM would add 15 and 40 (La B.) and 85 (McD.). The “Immortal 50th” has always been awarded “the Oscar”, but this game was “all McDonnell”, and there are other good candidates in which both masters were on the top of their form. In some one feels the wrong man won; though McDonnell lost 40 (a King’s Gambit in which he gave up two pieces in the first nine moves), he actually harried La Bourdonnais with his inferior force for 22 more moves before he was finally shaken off by the Frenchman’s knife-edge accuracy.

But only 12 “Royal Battles” have been mentioned. What of the 73 “plebeians” remaining? Many are curate’s eggs, excellent up to more than half-way through, then addled by blunders, McDonnell being the worse offender. But others are rated by “H.G.” in A History of Chess as thoroughly bad eggs throughout, and this is difficult to dispute. In his disastrous first match McDonnell, playing White against the Sicilian, repeatedly makes such a crude hash of the opening that his king (with both his rooks and bishops still unmoved) is forced to make a fatuous excursion via KB2 to KR3, where he is speedily run over like a stray cow on a railway line. As for La Bourdonnais, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that before, instead of after, he played the 58th and 83rd games, he had, as was his nightly custom, “sent pint after pint of Burton Ale Beer into the hold”.

The whole series is given in Walker’s “Thousand Games” – the 47th game described above also appears in Staunton’s Laws and Practice of Chess, Greenwell’s Chess Exemplified, R.N. Coles’ Battles-Royal of the Chessboard, and the BCM, July 1934 with notes by Sir Stuart Milner-Barry.’

7370. Randomized chess

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) submits a game from pages 248-250 of Sissa, 1853:

Baron van der Hoeven – Spoelstra

Nijmegen, 1852

1 e3 d5 2 Bf3 f6 3 Nd3 e5 4 e4 b6 5 Bg4 dxe4 6 Bxc8 exd3 7 Bh3 dxc2+ 8 Rxc2 Qe4 9 f3 Qd3 10 Re1 Nd6 11 Re3 Qg6 12 Ng3 Nc4 13 Re2

13...h5 14 Bf5 Qg5 15 Bd3 Na5 16 b4 Nb7 17 Qc3 Nf7 18 Be3 Qh4 19 Nf1 Nfd6 20 Bf2 Qg5 21 Ng3 Qh4 22 Ne4 Qxh2 23 Nxd6 Nxd6 24 Qc6 f5 25 g3 e4 26 Bc5 Qxg3 27 Bxd6 Qxd6 28 Qxd6 cxd6 29 fxe4 f4 30 e5 f3 31 Rf2 dxe5 32 Be4 Bh4 33 Rxf3 Rxf3 34 Bxf3 Bh7 35 Bxh5 Bxc2+ 36 Kxc2 Kc7 37 Bg6 Kd6 38 Kc3 Ke6 39 d4 Be1+ 40 Kc4 exd4 41 a3 Bf2 42 Kb5 Kf6 43 Bd3 g5 44 a4 g4 45 Kc4 Ke5 46 Be2 g3 47 Bf3 Kf4 48 White resigns.

7371. Memories of Pillsbury

From a letter contributed by Edward M. Weeks of Washington, DC on pages 1-2 of the April 1944 Chess Review:

‘I lived in Boston from Nov. ’87 to Nov. ’89. I was a member of the Boston YMCU on Boylston St. and played chess there in the evenings. In the Fall of ’88, Pillsbury, then a High School student, began to play there too and at first was easy pickings for most of us. I was a B class player, but by the Spring of ’89 he could beat the best of the group who frequented the chess room at the Union.On a number of occasions Pillsbury and I walked up over Beacon Hill together, I to my room and he on his way to Cambridge. Several times I advised him against letting chess get too great a hold on him as it would interfere with his advancement in other fields.

In the late Spring of ’89, Pillsbury won a game from one of the strongest players at the Boston Chess Club which he played over for our small group at the Union.’

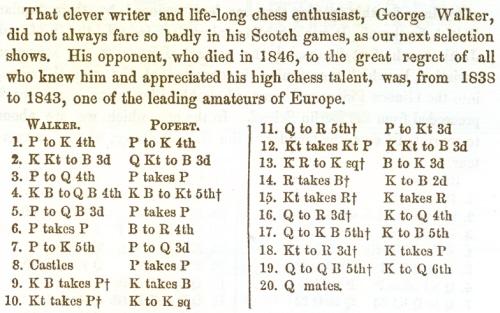

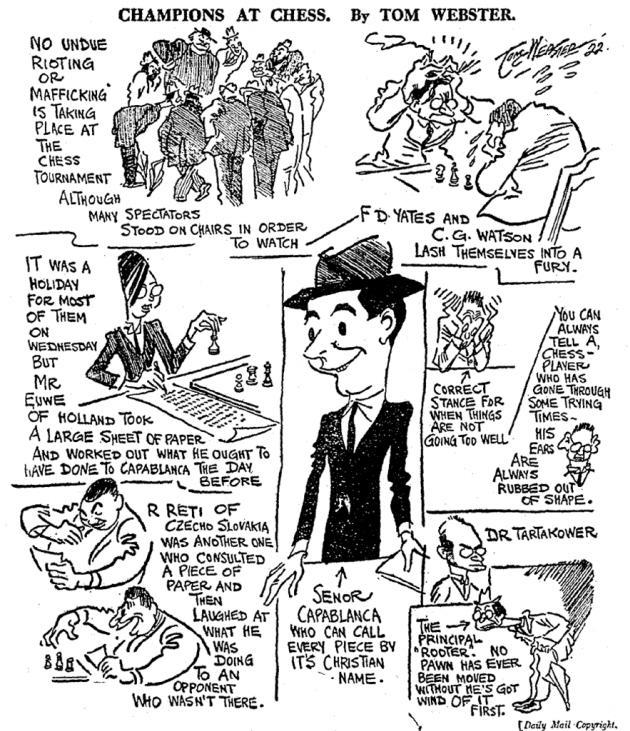

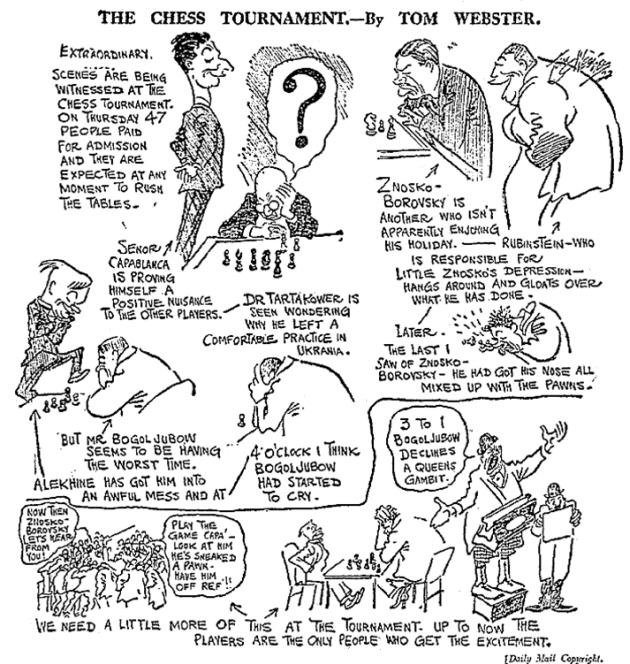

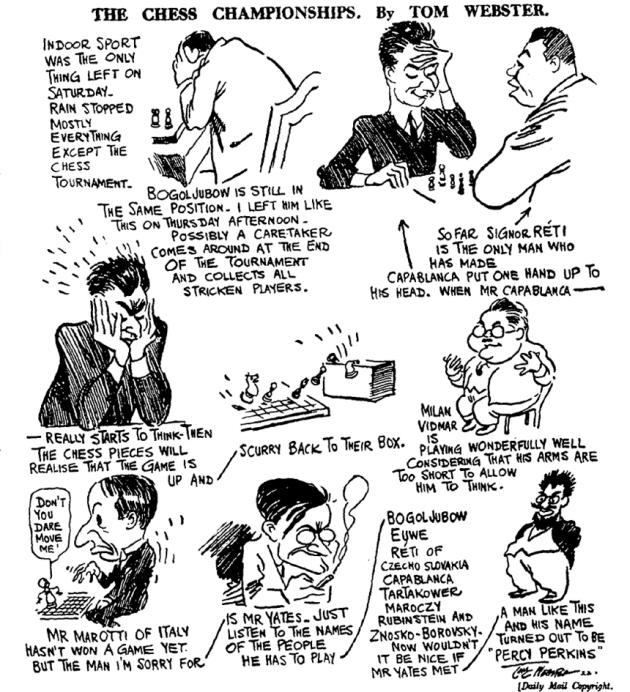

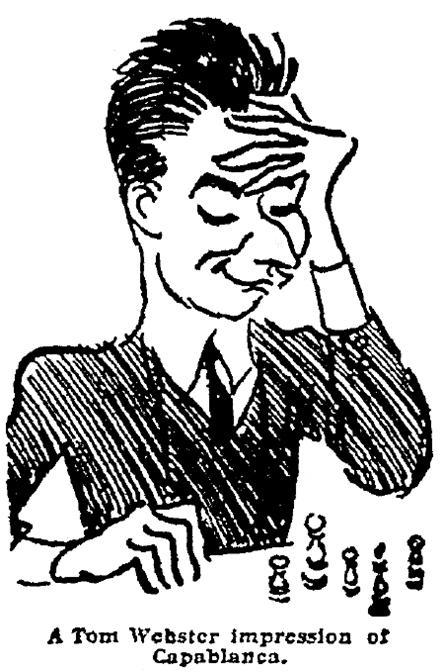

7372. London, 1922 cartoons (C.N. 3938)

Concerning the cartoons from Tom Webster’s Annual

1923 which were shown in C.N. 3938, Olimpiu G.

Urcan (Singapore) provides information on their prior

appearance in the Daily Mail:

Daily Mail, 3 August 1922, page 9

Daily Mail, 11 August 1922, page 9

Daily Mail, 14 August 1922, page 9

Daily Mail, 19 August 1922, page 9 (detail from the 14 August cartoon).

7373. Boden’s Mate (C.N.s 7341 & 7364)

Another specimen, with two sacrifices on c6:

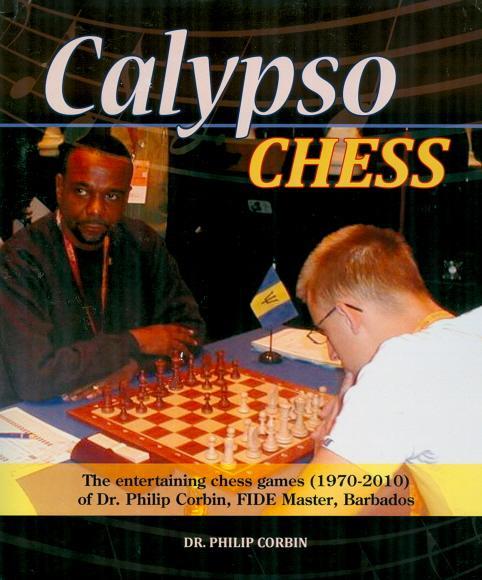

Philip Corbin – Othneil HarewoodBarbados (friendly game), 1979

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Nxc3 Nc6 5 Nf3 e6 6 Bc4 Bb4 7 O-O Bxc3 8 bxc3 Na5 9 Bd3 Qc7 10 Qe2 Nc6 11 Ba3 Ne5 12 Nxe5 Qxe5 13 f4 Qc7 14 e5 Qxc3 15 Bd6 Ne7 16 Rac1 Qd4+ 17 Kh1 Nc6 18 f5 h5 19 fxe6 dxe6 20 Rxf7 Bd7 21 Qf3 O-O-O

22 Qxc6+ Bxc6 23 Rxc6+ Resigns.

Source: pages 72-73 of Calypso Chess by Philip Corbin (Saint Peter, 2011).

There is much lively chess in this 441-page annotated games collection from Caribbean Chapters Publishing. Nigel Short’s Foreword remarks that ‘Dr Philip Corbin’s irresistibly infectious, boyish enthusiasm permeates its every page’.

Among the highlights are the games against Freedman (pages 60-61), Chubinsky (pages 93-95), N.N. (pages 121-122) and Greenidge (pages 223-224). The last of these reached a curious symmetrical position after six moves (1 b4 b5 2 e4 e5 3 Bb2 Bb7 4 Bxe5 Qe7 5 Bxc7 Bxe4 6 Qe2 Bxc2):

7374. Marshall correspondence game

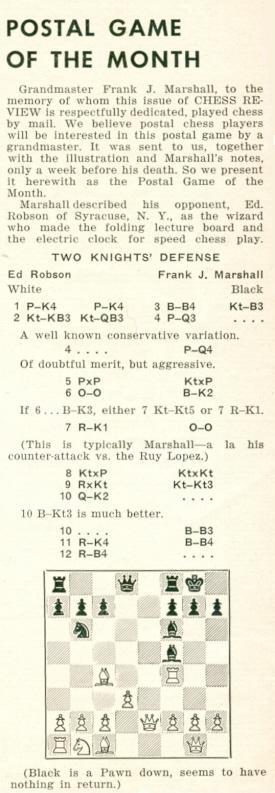

The last game in Frank Marshall, United States Chess Champion by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 1994) – see pages 361-362 – was played by correspondence against Ed Robson and is said to have ended ‘21 Rd1 g5! White resigns’. However, the following was published in the Marshall memorial issue of Chess Review (December 1944, pages 28-29):

7375. Tarrasch translations (C.N. 7359)

The list below is confined to volumes in our collection.

Tarrasch’s Das Schachspiel (Berlin, 1931) was translated into English by G.E. Smith and T.G. Bone as The Game of Chess (Chatto and Windus, London, 1935 and David McKay Company, Philadelphia, 1935). It was reprinted by David McKay Company, Inc., New York in 1976 and by Dover Publications, Inc., New York in 1987. An algebraic edition edited by Lou Hays and David Sewell was brought out by Hays Publishing, Dallas in 1994.

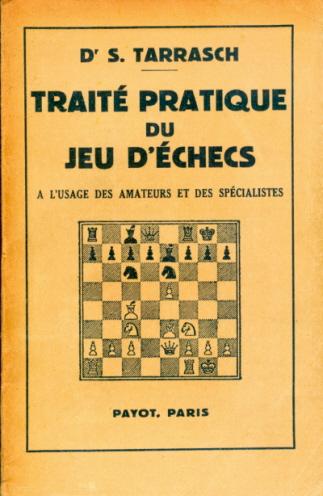

A French edition of Das Schachspiel, translated by René Jouan, was published by Payot, Paris in 1952 under the title Traité pratique du jeu d’échecs. The company has reprinted it many times.

Dreihundert Schachpartien, of which Tarrasch produced a number of editions, was the subject of an English translation, Three Hundred Chess Games, in two volumes published in 1959 and 1961. The translators were Robin Ault and John Kirwan for volume one (which included games 1-119) and Robin Ault for volume two. (Preparation of this item has revealed that our collection lacks volume two, and we shall be glad to hear from any reader with a copy for sale.) Another English translation of the book, also entitled Three Hundred Chess Games, was by Sol Schwarz, brought out by Hays Publishing, Park Hill in 1999. A Russian translation by V.I. Murakhveri, 300 shakhmatnykh partii, came from Fizkultura i sport, Moscow in 1988. In 2007 Caissa Italia editore, Rome published an Italian translation, 300 partite di scacchi, by Alex Tonus.

Die moderne Schachpartie, of which several editions appeared, has been translated into Russian by V.I. Murakhveri, in two volumes, under the title Uchebnik shakhmatnoi strategii (AST, Moscow, 2001).

Das internationale Schachturnier des Schachclubs Nürnberg im Juli-August 1896 by Tarrasch and C. Schröder (Leipzig, 1897) was translated into English by John C. Owen as Nuremberg 1896 International Chess Tournament (Caissa Editions, Yorklyn, 1999).

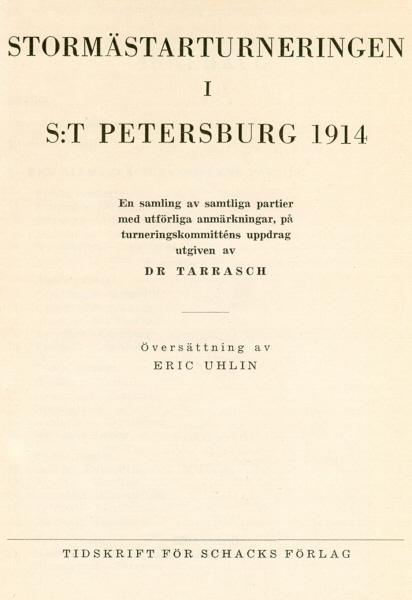

Tarrasch’s Das Grossmeisterturnier zu St. Petersburg im Jahre 1914 (Nuremberg, 1914) was translated into Swedish by Eric Uhlin as Stormästarturneringen i S:t Petersburg 1914 (Tidskrift för Schacks Förlag, Örebro, 1955). In 1993 Caissa Editions, Yorklyn published St Petersburg 1914 International Chess Tournament, translated by Robert Maxham.

We are grateful to Tony Peterson (Southend-on-Sea, England) and Robert Sherwood (E. Dummerston, VT, USA), who have written to us on this topic.

From pages 7-8 of Traité pratique du jeu d’échecs:

‘Le plus grand charme du jeu vient de ce qu’il est une réalisation intellectuelle et les réalisations intellectuelles sont parmi les plus grandes jouissances de l’existence, si même elles ne sont pas les plus grandes. Tout le monde ne peut écrire une pièce de théâtre, construire un pont, voire faire un bon mot. Mais, dans le jeu d’échecs tout le monde peut et doit créer intellectuellement et savourer ce plaisir de choix. J’éprouve toujours un peu de pitié pour ceux qui ne savent pas y jouer, comme j’en ai pour ceux qui n’ont jamais connu l’amour. Les échecs, comme l’amour, comme la musique, ont la possibilité de donner du bonheur à l’homme.

C’est le chemin qui conduit à ce bonheur que j’ai voulu enseigner dans ce livre.’

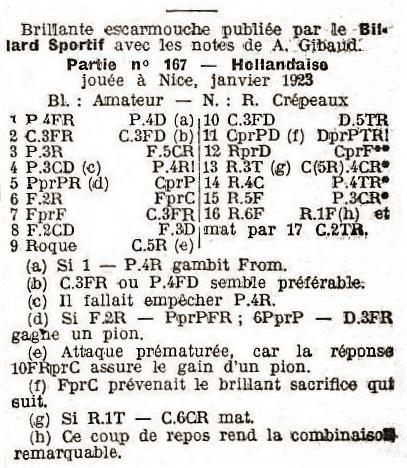

7376. N.N. v Crépeaux

1 f4 d5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 e3 Bg4 4 b3 e5 5 fxe5 Nxe5 6 Be2 Bxf3 7 Bxf3 Nf6 8 Bb2 Bd6 9 O-O Ne4 10 Nc3 Qh4 11 Nxd5

11...Qxh2+ 12 Kxh2 Nxf3+ 13 Kh3 Neg5+ 14 Kg4 h5+ 15 Kf5 g6+ 16 Kf6

16...Kf8 17 White resigns.

Reminiscent of Lasker v Thomas, this well-known gamelet (‘Amateur v Crépeaux, Nice, 1923’) is to be found, with criticism of both sides’ play, on pages 399-400 of Echec et mat de l’initiation à la maîtrise by Frank Lohéac-Ammoun (Les Avirons, 2011). Han Bükülmez (Ecublens, Switzerland) wonders whether it can be demonstrated that the game is genuine.

Although the venue is usually given as Nice, page 272 of 200 Miniature Games of Chess by J. du Mont (London, 1941) had ‘Holland, 1923’. It is by no means easy to build up a list of early appearances of the game in print, and readers’ assistance will be appreciated.

A photograph of Robert Crépeaux, from the September 1925 issue of L’Echiquier, was included in C.N. 3479. He died in 1994 (see Europe Echecs, April 1994, page 13), although Lohéac-Ammoun’s book states (page 399) that Crépeaux ‘mourut prématurément à Paris en 1944’. Indeed, the book’s undoubted qualities are marred by many errors in dates and names. For instance, it is claimed on page 33 that the famous game Capablanca v Fonaroff was played in 1904.

7377. Hungarian team

From page 153 of the September-October 1930 American Chess Bulletin:

7378. Who?

7379. Letter written by Labourdonnais

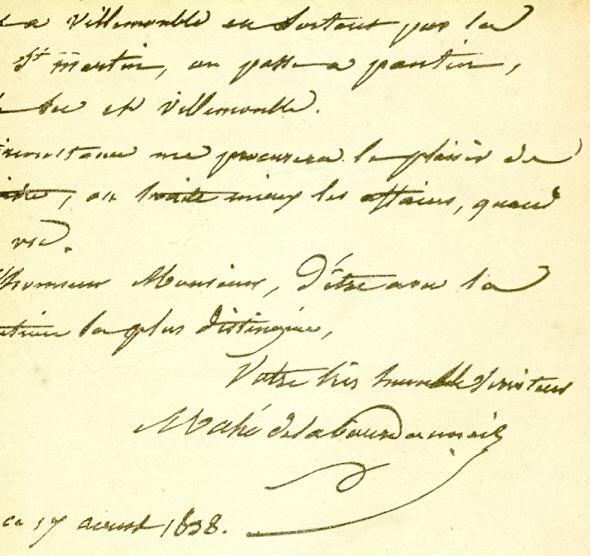

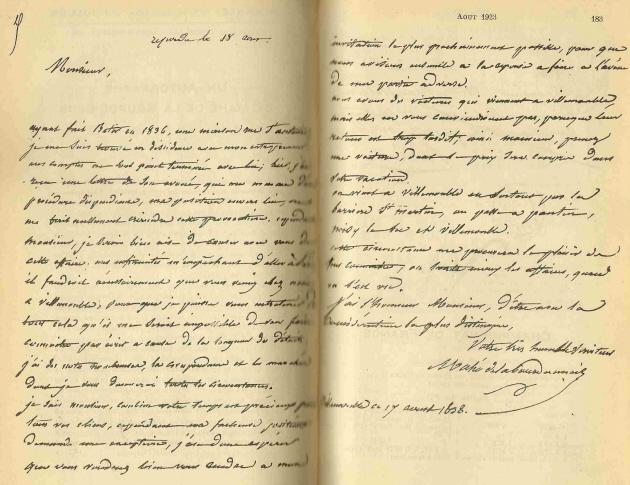

Pages 182-183 of the August 1923 issue of La Stratégie reproduced a letter written by Labourdonnais in 1838.

Unable to scan the full document from our bound volume, we wonder whether a reader could kindly provide a copy for reproduction here.

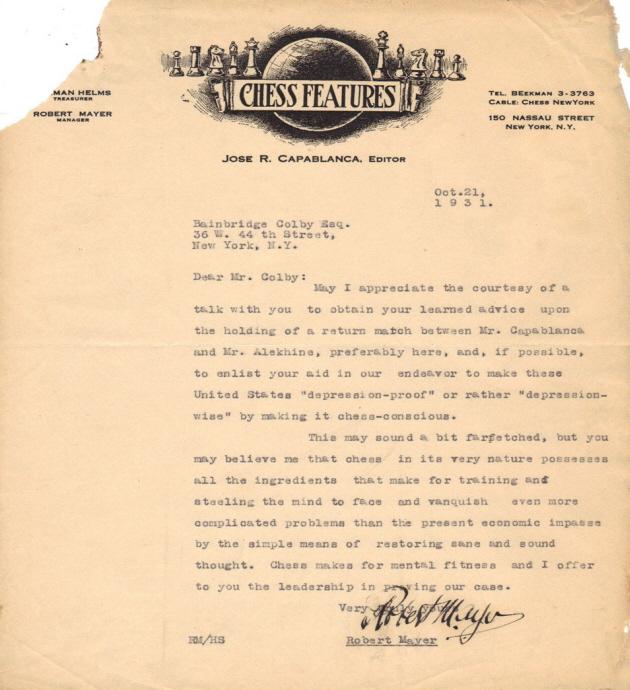

7380. Chess Features (C.N.s 2849 & 3560)

C.N.s 2849 and 3560 mentioned that we possess two sheets of stationery with Capablanca named as the editor of Chess Features. Now, Joed Miller (HNP, HI, USA) has sent us the following letter dated 21 October 1931 from Robert Mayer to Bainbridge Colby (a former Secretary of State):

7381. N.N. v Crépeaux (C.N. 7376)

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) supplies references to three appearances of the game in print: Bulletin de La Fédération Française des Echecs, April-June 1923, page 10; the column by Gaston Legrain in L’Action Française, 8 April 1923, page 5; Bulletin de La Fédération Française des Echecs (July 1927, page 22).

All three items have the same annotations by Aimé Gibaud. Two of them state that the game was played in January 1923 and that it had previously been published in the periodical Le Billard Sportif (which has not yet been found).

Below is what appeared in L’Action Française:

7382. G.S. Spreckley

From Adrian Harvey (Edgware, England):

‘I wonder whether anyone has a picture of George Stormont Spreckley, the Secretary of the Liverpool Chess Club in the 1840s and a regular opponent of Augustus Mongrédien. Spreckley was a good chessplayer who secured victories in individual games against quite dangerous opponents, including Harrwitz and Williams. I had an article published on him in the October-December 2007 issue of Kaissiber and am currently working on an article about the short, turbulent time he spent working as a merchant in Shanghai during the Taiping Rebellion.’

7383. Letter

written by Labourdonnais (C.N. 7379)

Alain Biénabe (Bordeaux, France) has supplied a scan of the full letter:

| First column | << previous | Archives [88] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.