Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [87] | next >> | Current column |

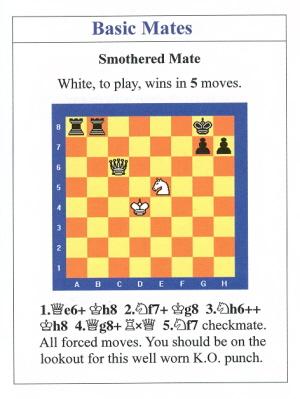

7297. Mate in four (C.N. 5923)

From page 11 of Wiseman’s Chess Primer by Paul Wiseman (Rothersthorpe, 2011):

7298. Café de la Régence

Jean-Olivier Leconte (Saint-Mandé, France) reports that he has recently created a webpage devoted to the Café de la Régence.

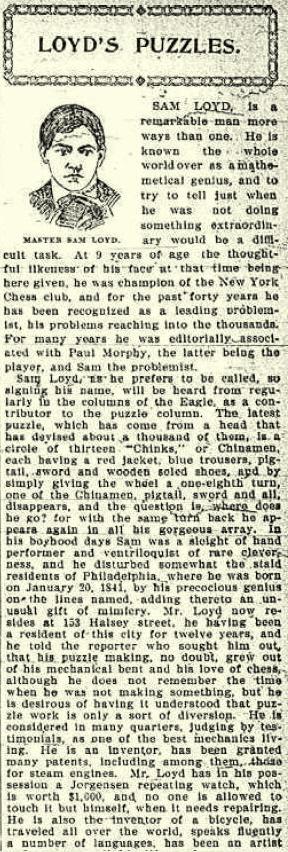

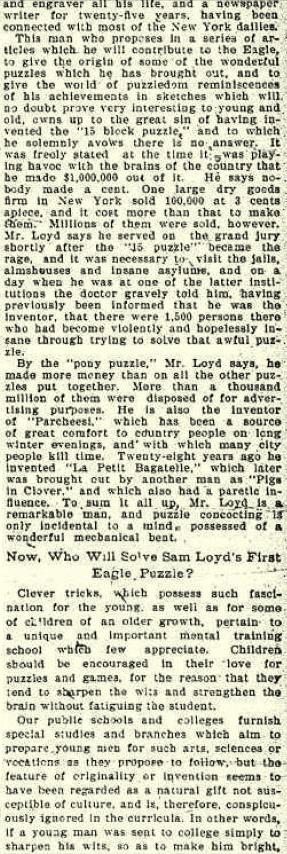

7299. Samuel Loyd

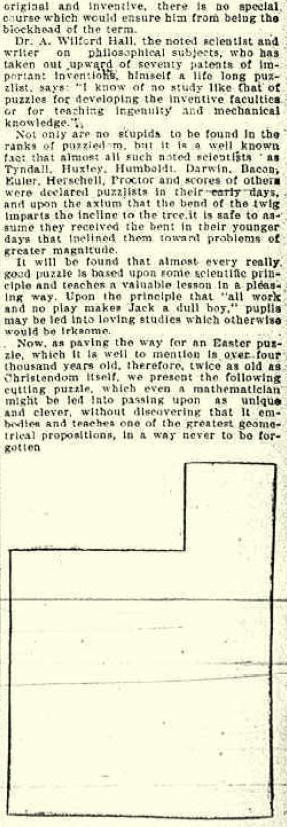

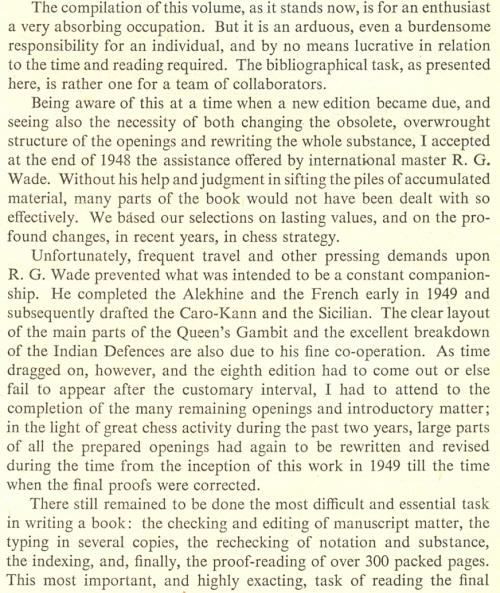

We thank Russell Miller (Vancouver, WA, USA) for pointing out the full text of the article about Samuel Loyd mentioned in The Caissa-Morphy Puzzle. It comes from page 23 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 22 March 1896:

7300. R.G. Wade and Modern Chess Openings (C.N. 7295)

From Leonard Barden (London):

‘Bob Wade did indeed believe that he would be credited on the title page as the editor of Modern Chess Openings, as he told me several times, including in 1949 when he enlisted me to write a section on the Queen’s Gambit Declined. He claimed to have done the great majority of the work entailed in the book’s revision.

He was angry at what he perceived as Korn’s diminishing of his contribution when Modern Chess Openings appeared, and vowed that he would never work with Korn again.’

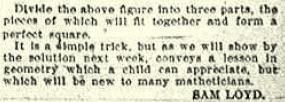

Below is the relevant part of Walter Korn’s Preface to the eighth edition of Modern Chess Openings (London, 1952), i.e. from pages v-vi:

The following page had this acknowledgement:

The ninth edition (‘completely revised by Walter Korn and John W. Collins’) was published in 1957. In referring to earlier editions, Korn’s Preface (pages v-vi) made no mention of Wade, stating ‘... the eighth edition was both directed and revised by me’. On page iii of the Preface to the tenth edition (London, 1965) this became ‘... the eighth edition was both directed and solely revised by me’. On page v of the eleventh edition (London, 1972) Korn’s Preface stated, ‘I subsequently also directed and revised the eighth edition’.

Shortly after the eighth edition appeared, CHESS (August 1952, page 214) published a review which included the following:

‘W. Korn claims, on the dust-cover, to be an international master. There is no master on the official FIDE list named Korn. Is Korn an assumed name? We cannot recall seeing his name in any international tournament since we have known him as W. Korn. When we peruse the sections which he acknowledges were done by R.G. Wade, we note a contrast. Wade is willing and able to dogmatize, he is interested in the chess, reveals clearly the various systems and passes the judgments we want ... It seems clear that the last word in MCO should always come from a practising master ...

Wade’s work on the French, Caro-Kann, Sicilian, Queen’s, etc., though already a little out of date (most of it was finished three years ago and it has obviously been hardly touched since) is the best he has ever done, and a lasting contribution to chess literature. It is not only better than the rest, it is better than most that has appeared in MCO before.’

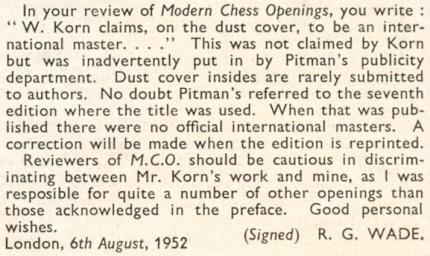

Wade wrote on page 236 of the September 1952 CHESS:

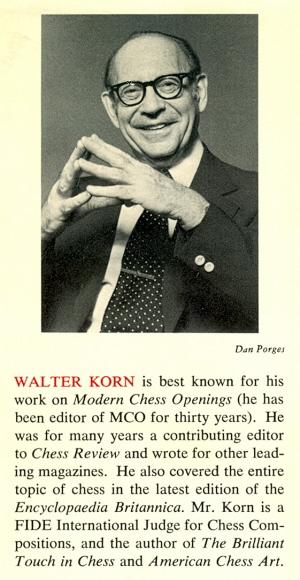

From the dust-jacket of America’s Chess Heritage by Walter Korn (New York, 1978):

7301. Moscow, 1936 (C.N. 7289)

Philippe Pierlot (Le Perchay, France) has provided a good-quality copy of the Moscow, 1936 group photograph (source not yet identified):

7302. Winawer at Nuremberg, 1883

From Mike Salter (Sydney, Australia):

‘Is there any primary source to confirm the tale that Winawer had not intended to play at Nuremberg, 1883 (his last great tournament success) but was collared by the organizers just prior to the event, while he was passing through the city in search of a dentist?’

Such a story appears in Winawer’s entry in the Oxford Companion to Chess, without any source.

We have found this passage on page 354 of the August 1883 Chess Monthly:

‘[Winawer] had no intention to take part in the tournament. On a journey from Hamburg to Vienna he arrived at Nuremberg and, suffering acutely from toothache, he stopped to get professional advice, when walking to the town he accidentally met Mason, who accompanied him to a dentist. Whilst waiting for the next train to Vienna, the Committee were apprised of his presence, and persuaded him to play in the tournament. More lucky than the first King of Israel, who went out in search of a useful domestic animal, which somehow got astray, and found a crown in its stead, Winawer exchanged a bad tooth for a chess crown.’

Hoffer, the co-Editor of the Chess Monthly, attended the Nuremberg tournament.

This photograph of Winawer comes from page 161 of the

February 1893 Chess Monthly:

7303. Chess and insanity (C.N.s 6494 & 7260)

Sean Tobin (Phoenix, AZ, USA) asks:

‘Have any serious professional studies been published on the historical incidence of insanity in top-level chess? Does insanity strike more players, on average, than other groups of people?’

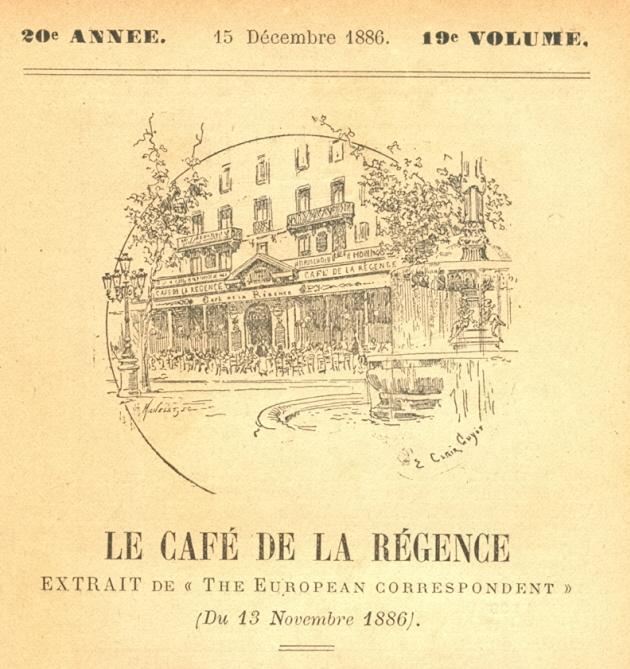

7304. Café de la Régence (C.N. 7298)

Below is a list, far from exhaustive, of articles on the Café de la Régence and its habitués which we have come across in old chess periodicals:

- ‘A Visit to the Café de la Régence’ by G. Walker, Frazier’s

Magazine, 1840 and reproduced, inter alia,

in Brentano’s Chess Monthly, August-September

1882, pages 176-181. See also pages 76-89 of The

Treasury of Chess Lore by F. Reinfeld (New York,

1951);

- ‘Die letzte Berühmtheit des Café de la Régence’ in Deutsche Schachzeitung, October 1853, pages 316-318;

- ‘Das Café de la Régence in Paris, wie – es war’ by G.R. Neumann in Deutsche Schachzeitung, January 1871, pages 1-8;

- ‘The Régence under the Old Masters’ by A. Delannoy in the Chess Monthly, September 1880, pages 3-5; October 1880, pages 36-37; November 1880, pages 71-74;

- ‘The Café de la Régence’ by T. Tilton, in the Chess Monthly, December 1886, pages 100-104 and the International Chess Magazine, December 1886, pages 359-365. Reproduced from the European Correspondent, 13 November 1886. A French translation, ‘Le Café de la Régence’, was published in La Stratégie, 15 December 1886, pages 353-360;

- News item, La Stratégie, 15 September 1892, pages 274-275;

- ‘An Old French Coffee-House’ by the Paris correspondent of the Neue Freie Presse, in Checkmate, January 1904, pages 61-62;

- ‘Au Café de la Régence’ by A.G. in La Stratégie, May 1911, pages 177-178;

- ‘Le Café de la Régence’ in Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français, 1925, pages 65-75;

- ‘In Re the Café de la Régence’ by E.J. Clarke in The Gambit, December 1928, pages 373-374.

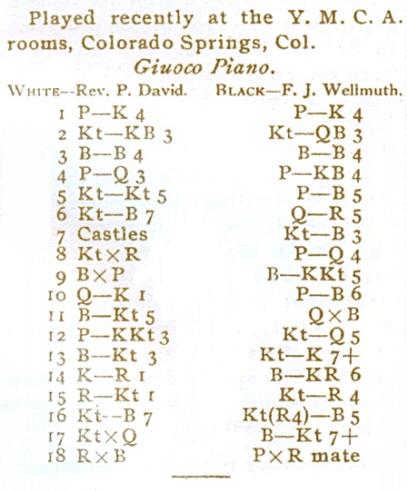

7305. Wellmuth and Dubois

A game on page 15 of the Canadian magazine Checkmate, October 1903 was attributed to F.J. Wellmuth:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 d3 f5 5 Ng5 f4 6 Nf7 Qh4 7 O-O Nf6 8 Nxh8 d5 9 Bxd5 Bg4 10 Qe1 f3 11 Bg5 Qxg5 12 g3 Nd4 13 Bb3 Ne2+ 14 Kh1 Bh3 15 Rg1 Nh5 16 Nf7

16...Nhf4 17 Nxg5 Bg2+ 18 Rxg2 fxg2 mate.

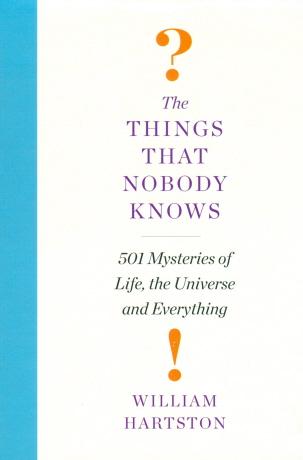

This game has frequently been published as won by Serafino Dubois (1817-99), with contradictory information as to the occasion (a range of dates in the 1850s and 60s). For example, page 46 of Chess Sparks by J.H. Ellis (London, 1895) named White as ‘General M.’ and stated that the game was ‘played at Rome, about 1867’. On page 50 of Serafino Dubois il Professionista by Alessandra Innocenti and Lorenzo Barsi (Brescia, 2000) the game-score was given without any place or date, and White was merely ‘N.N.’.

The earliest publication that we have found is on page 203 of the July 1858 Chess Monthly, which specified that the game had been played in Rome in 1850 against an ‘amateur’:

It will be noted that the game on the previous page was between Dubois and ‘General M***e’. The Chess Monthly of the following year had three other encounters between the same players.

When the game which ended with 18...fxg2 mate appeared on pages 112-113 of the April 1859 Deutsche Schachzeitung (also with the specification Rome, 1850), White was identified as ‘Hr. General M.’. We wonder whether the German magazine miscopied from the Chess Monthly or obtained its information from another source.

7306. A perfectly played game

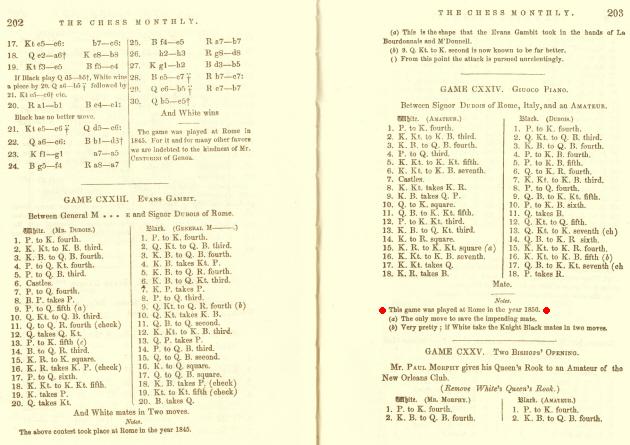

William Hartston’s new book The Things That Nobody Knows (C.N. 7280) has one item about chess, which we reproduce from pages 166-167 with the author’s permission:

‘What is the result of a chess game if both sides play perfectly?

With best play, the game of noughts-and-crosses (tic-tac-toe in the USA) should end in a draw, as it is not difficult to demonstrate. In the more complex game of Connect Four, it was shown by exhaustive analysis in 1974 that the first player can force a win. The still more challenging game of gomoku (five in a row) was solved by computer in 1994, showing that the first player may again force a win with best play. But what about chess?

Results from international tournaments have supported the general view that White, who moves first, has an advantage, with results for White around 2 or 3 per cent ahead of Black. With around 10120 possible chess games (which is significantly more than the number of atoms in the universe, estimated at around 1080), a complete analysis of chess is currently impossible. Whether White’s advantage is enough to win, or whether Black can defend himself, or whether indeed with best play Black should actually win, at present appear to be unfathomable questions.’

It is certainly a widely discussed issue. Two passages from nineteenth-century books may be mentioned here, the first being on page xxxi of The Modern Chess Instructor by W. Steinitz (New York, 1889):

‘In fact it is now conceded by all experts that by proper play on both sides the legitimate issue of a game ought to be a draw, and that the right of making the first move might secure that issue, but is not worth the value of a pawn.’

From pages 74-75 of Maxims and Hints by R. Penn (London, 1842):

‘Every game perfectly played throughout on both sides would be by its nature drawn. Since, then, in matches between the most celebrated players and clubs of the day some of the games have been won and lost, it seems to follow that there might be better players than have been hitherto known to exist.’

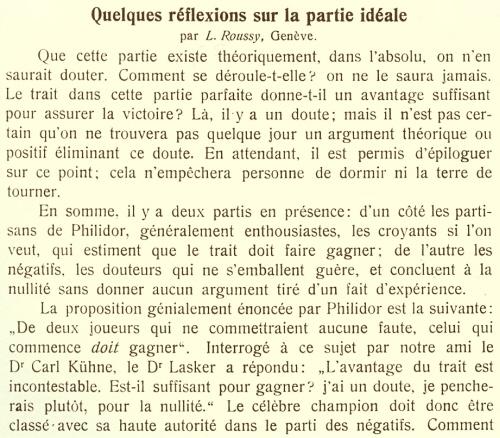

We recall too the article ‘Quelques réflexions sur la partie idéale’ by L. Roussy which was published, together with comments by Erwin Voellmy, on pages 54-58 of the April 1919 Schweizerische Schachzeitung/Revue suisse d’échecs:

The article also appeared on pages 134-137 of the June 1919 La Stratégie. Page 299 of the September 1919 BCM noted Roussy’s conclusion that White wins a perfectly played game but remarked that ‘M. Roussy does not go so far as to produce an example of a game perfectly played by both sides, in which the victory goes to White’. A book prize was offered by the BCM to ‘the reader who shall be adjudged to have sent in the nearest approach to “perfection”’.

B. Goulding Brown expressed doubts about Roussy’s thesis in a letter on pages 334-335 of the October 1919 BCM but added:

‘... undoubtedly the advantage of first move, added to that gained from one slightly objectionable move on Black’s part, will produce a winning advantage for White, as in the game H.E. Atkins v J.F. Barry (Cable Match, 1910), which I beg to enclose as the nearest that I know to perfection.’

Regarding that game, see pages 142-143 of A Chess Omnibus.

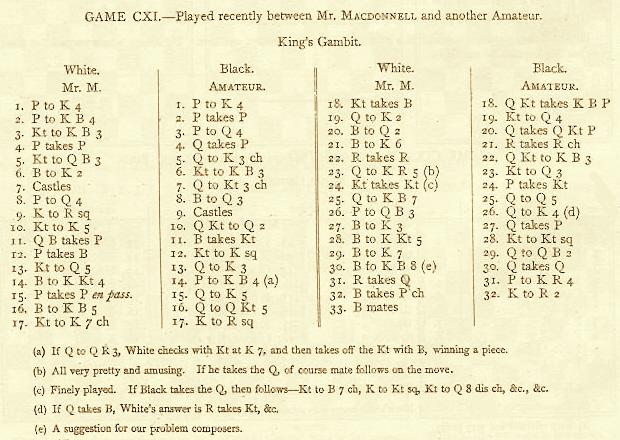

7307. MacDonnell v Amateur (C.N. 7294)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 d5 4 exd5 Qxd5 5 Nc3 Qe6+ 6 Be2 Nf6 7 O-O Qb6+ 8 d4 Bd6 9 Kh1 O-O 10 Ne5 Nbd7 11 Bxf4 Bxe5 12 dxe5 Ne8 13 Nd5 Qe6 14 Bg4 f5 15 exf6 Qe4 16 Bf5 Qb4 17 Ne7+ Kh8 18 Nxc8 Ndxf6 19 Qe2 Nd5 20 Bd2 Qxb2 21 Be6 Rxf1+ 22 Rxf1 Ndf6 23 Qh5 Nd6 24 Nxd6 cxd6 25 Qf7 Qd4 26 c3 Qe5 27 Be3 Qxc3 28 Bg5 Ng8 29 Be7 Qc7 30 Bf8 Qxf7 31 Rxf7 h5 32 Bxg7+ Kh7 33 Bf5 mate.

Our reason for giving this game, from page 140 of the Westminster Papers, 1 January 1873, is that – as noted by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) – in this position ...

... play is said to have continued 16 Bf5 Qb4, whereby Black places his queen en prise.

A likely explanation is that the magazine inverted the 16th and 17th moves.

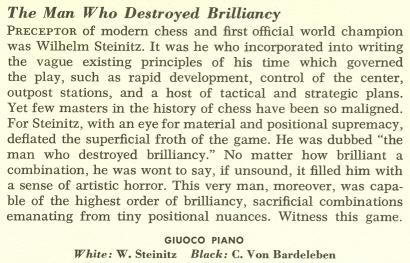

7308. Steinitz and brilliancy

From page 45 of All About Chess by I.A. Horowitz (New York, 1971):

What evidence is there that Steinitz was dubbed ‘the man who destroyed brilliancy’?

The subsequent remark above is more familiar. For example, the following is on the dust-jacket of Chess Traps, Pitfalls, and Swindles by I.A. Horowitz and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1954):

‘The great Steinitz once wrote: “A win by an unsound combination, however showy, fills me with artistic horror.”’

We do not recall seeing that ‘once’ observation in Steinitz’s writings, but this comes from the article ‘Wilhelm Steinitz, Genius’ by Robert J. Buckley on pages 176-177 of the March 1913 Chess Amateur:

‘“The sound game is the true game”, he used to say. Also, “A win by an unsound combination, however showy, fills me with artistic horror”.’

Buckley’s article began with the statement ‘Wilhelm Steinitz, whom I knew intimately for 20 years ...’ The full text has been added to Who Was Robert J. Buckley?

7309. Kingpin

We note that nowadays the Kingpin website is regularly updated.

7310. An unknown Nimzowitsch v Marshall game

Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark) has sent us a game which will be appearing in the book he has written with Jørn Erik Nielsen, Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 (C.N. 7108). It was a ‘serious game’ played at the Börsen Café, Riga, and the co-authors believe that it has not been published until now, except in the Riga press of the time.

Aron Nimzowitsch – Frank James MarshallRiga, 26 January 1912 (new style)

Petroff Defence

(Annotations by Nimzowitsch, translated by Per Skjoldager and Jørn Erik Nielsen)

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 d6 4 Nf3 Nxe4 5 Nc3 d5 Involves a promising sacrifice of a pawn. Normally 5...Nxc3 6 dxc3 Be7 7 Bd3 is played, with a somewhat better game for White. 6 Qe2 Be7 7 Nxe4 dxe4 8 Qxe4 O-O 9 Bc4 Bd6 10 O-O Re8 11 Qd5 The introduction to a faulty combination. 11 Qd3 was better. 11...Be6! 12 Qxb7 Bxc4 13 Qxa8

13...Bd5! White had overlooked this move in his calculations. Now, he loses his queen but obtains quite a lot of wood in return. Bad was 13...Bxf1 14 Kxf1 Qe7 15 g3 c6 16 d3 Qd7 17 Be3 and the queen will be saved. Also 13...Bc5 was less strong than the text move since 14 d4 (not 14 Qb7 because of 14...Bb6!) 14...Bb6 15 Bg5 f6 16 Rfe1! Rxe1+ 17 Rxe1 fxg5 18 Qe4 and White has two pawns for the exchange and a good game. 14 Qxd5 Bxh2+ 15 Kxh2 Qxd5 16 d3 h6 17 Bd2 A fine move! White intends to put the black knight out of action by means of Bc3, i.e. to deprive him of the squares f6 and e5. 17...Nd7 18 Bc3 Re6 19 Rae1 Rg6 20 Re3 Nf6 The a2 pawn is not worth much since the already weak pawns on the black queen’s flank then become even more vulnerable (after Ra1). 21 Bxf6 Rxf6 22 b3 Qa5 23 a4 Qc3 24 Re2

24...Re6! 25 Rfe1 Rc6! A fine point! The rook should not be immediately placed on c6 because of 24...Rc6 25 Re8+ Kh7 26 Ne5 Rc5 27 Nd7 and perpetual check. With the rook placed at e1, Ne5 is not possible any more because of Qxe1. 26 Re8+ Kh7 27 R1e4! Qb2 28 Ne1 Rxc2 This must, if at all, happen immediately; otherwise 29 Rc4 Rxc4 30 dxc4 with a bombproof position. This attempt to split the pawns by means of the sacrifice of the exchange only fails to the vivid defence by White. 29 Nxc2 Qxc2 30 Rf4! The only move in order to avoid the loss of a pawn.

30...Qc5! A beautiful protection. 31 Re1! a5 32 Kg1 Qc3 33 Rf1 Qxb3 34 Rc4 Qxd3 35 Rxc7 Qd4 36 Rxf7 Qxa4 37 Rf3! The isolated a-pawn cannot be saved after this move. 37...Qa2 38 Re1 a4 39 Ree3 Qb2 40 Ra3 Qb4 41 Ra1! Qd4 42 Rfa3 The game could have been drawn at this point. White still made attempts to win the game by attacking the g-pawn from behind, which Black however knew how to parry with the threat of perpetual check. 42...Qe5 43 Rxa4 Drawn.

Source: page 3 of Feuilleton-Beilage der “Rigaschen Rundschau”, 10 February 1912 (new style).

Mr Skjoldager adds that Nimzowitsch’s encounter with

Capablanca in Riga (game 22 in My Chess Career)

was also played at the Börsen Café, Sandstrasse 11 (now

Smilsu lela), as were the Cuban’s two simultaneous

displays around the same time. In the photograph below,

which dates from the early twentieth century, our

correspondent notes that the Café is the white building on

the left, behind the driver of the horse and carriage:

7311. Who? (C.N. 7292)

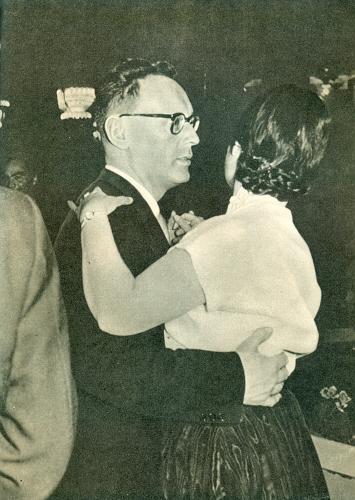

Knud Lysdal (Grindsted, Denmark) notes that the dancer is Botvinnik’s wife, Gayane. We reproduced the photograph from opposite page 32 of Botwinnik lehrt Schach by H. Müller (Berlin-Frohnau, 1967). The one below is from opposite page 96 of Twelfth Chess Tournament of Nations by S. Flohr (Moscow, 1957):

7312. Mieses v Billecard

From Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) comes this game on page 7 of The Standard (London), 11 January 1897:

Jacques Mieses – Maurice Billecard

Nuremberg, 1896

Scotch Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nxc6 bxc6 6 e5 Qe7 7 Qe2 Nd5 8 c4 Ba6 9 b3 Qc5 10 Bb2 Nf4 11 Qd2 Ne6 12 f4 g6 13 g4 Bh6 14 g5 Bg7 15 Na3 h6 16 O-O-O Qe7 17 Nc2 hxg5 18 Ba3 c5 19 f5 gxf5 20 Ne3 Bxe5 21 Qd5

21...Bf4 22 Qxa8+ Nd8 23 Kb1 Bb7 24 Qxa7 Bxe3 25 Bd3 Bxh1 26 Rxh1

26...Qd6 27 Bxf5 Rxh2 28 Rf1 Qd2 29 Bc1 Qe2 30 Qa4 c6 31 Qa7 Qxf1 32 Qxd7+ Kf8 33 Qd6+ Kg7 34 Qe5+ f6 35 Qe7+ Nf7 36 White resigns.

As regards the opening, see Kasparov, Karpov and the Scotch. Drawing attention to the remark in The Standard that Billecard ‘entered the Hastings Amateur Tournament under a pseudonym’, our correspondent comments:

‘The only participant in the Amateur Tournament who was living in Paris was “Flies”. He finished last in his section.’

That section was won by H.E. Atkins, and the overall victor of the tournament (which took place on 19-24 August 1895) was G. Maróczy. The report on pages 373-376 of the September 1895 BCM referred to ‘Monsieur Flies, of Paris’. See too C.N. 4798. It has yet to be discovered where and when Billecard died.

7313. Jakob/Jacques Mieses

From page 129 of Impact of Genius by R.E. Fauber (Seattle, 1992):

‘Jakob Mieses was born on 27 February 1865 of well-to-do Jewish parents in Leipzig, Saxony. His parents reared him with a classical education and a penchant for being stylish. He felt Jacques a more stylish name and retained a fondness for pince-nez glasses his life long.’

Is corroboration available concerning the Jakob/Jacques matter?

Jacques Mieses

7314. ‘Mrs Marza’

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) asks about the Indian chessplayer ‘Mrs Marza’ who is shown playing S. van Mindeno in a Corbis photograph taken at the British Chess Championships in London in August 1932, with Sir Umar Hayat Khan in the background.

We note that she was mentioned twice, as ‘Mrs Murza’, in the 1932 BCM (September, page 370 and October, page 427). She finished equal 9th-11th in the First-class tournament, section B.

7315. ‘The most brilliant chessplayer in the West’

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) draws attention to this report from the Chicago Tribune of 20 April 1879:

‘Another old-time chessplayer gone

Mr E.A. Dudley, who 30 years ago was the most brilliant chessplayer in the West, and perhaps in the country, died at Quincy, Ill., on the 11th inst, aged 73. He was pronounced by the famous Löwenthal, with whom he played a match in 1850 (won by Herr L.), the strongest player that the Hungarian had found in the United States. Mr Dudley was a native of Kentucky, a gentleman of rare intelligence and remarkable conversational powers. He was well known to the old chess world, and personally intimate with the early players of Chicago – Messrs. Morgan, Kennicott, Turner and others – who will regret to hear of his death. Below is a specimen of his play in 1847, which was contested in a tournament held at Blue Lick, Ky., against Dr Raphael, of Louisville, the winner of the fourth prize in the American Chess Tournament of 1857.’

The Dudley v Raphael game-score given by the Chicago Tribune: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Bc5 4 c3 d6 5 d4 exd4 6 cxd4 Bb4+ 7 Bd2 Bxd2+ 8 Nbxd2 Bd7 9 O-O Nf6 10 e5 dxe5 11 dxe5 Ng4 12 h3 Nh6 13 Re1 O-O 14 Bc4 Ne7 15 Qb3 Bc6 16 Rad1 Nef5 17 Ne4 Qe7 18 Neg5 Bxf3 19 Nxf3 b6 20 e6 Qf6 21 Rd7 Nd6 22 Rxc7 Rfc8 23 exf7+ Nhxf7 24 Ree7 Rxc7 25 Rxc7 and wins.

Our correspondent adds:

‘At the time of the 1847 Blue Lick tournament, Dudley (Lexington) and Raphael (Louisville) were considered the two “crack” players of the Western states, with a slight advantage in their individual encounters to Dudley; but on that occasion Raphael “led his antagonist some five games”. At the same meeting, Dudley beat the St Louis representatives J. Shaw (+18 –6=2) and R. Beattie (+11 –1 =1). Beattie succeeded in winning a majority of five games over Turner, and came out even with Dr Raphael (American Chess Magazine, 1847, pages 237-238).

According to Stanley, “Mr D.’s style of play is excellent. We are convinced that he and some others among our friends in Kentucky want but suitable practice, to become really first-rate players” (ibid., page 104).

Dudley performed creditably in his encounter with Löwenthal in 1850, as related by the European master himself:

“Mr Dudley paid us a visit, and a match was arranged for me with him, by Mr Turner. The winner of the first 11 games was to be the victor. The first game – a well contested one – was won by Mr Dudley, and if I had had sufficient English at my command, I should have said that such a game was worth losing. The second game, through a blunder on my part, also went to the score of my opponent. Mr Turner seemed somewhat startled at the turn affairs were taking, while I felt uneasy. In all the important matches I have played, I have lost the first two games. In consequence of my habit of mind, I take some time to become familiarized with my position, and able to apply myself thoroughly to what is before me; and this is so, whether my opponent happens to be equal or inferior to me. At the third game, I settled down to my work, and won that and the following five, and ultimately the match only by a majority of three games. This close play was, I think, owing to Mr Dudley often playing the Ruy López Opening in the Knight’s Game. That attack was not then sufficiently appreciated in Europe, and I was but little acquainted with the defence. I took the line of play given in the German Handbuch, and lost nearly every game. Mr Dudley played this opening with great skill and judgment. Since that time, I have had the opportunity of investigating this attack, and have prepared a defence which, if not completely satisfactory, seems to me far preferable to the old method.

I soon had my revenge – for in another match which followed immediately I won 11 games, Mr Dudley scoring only three. In this match I remember I adopted the defence to the Ruy López 3...P-KB4 with success, and though that move has not secured the approbation of the leading European players it is my individual opinion that it may as well be played as any other, and that, at all events, it gives the second player an open game.

After some days pleasantly spent with Mr Steward, Mr Lutz, and Mr Turner, Sen., a third match with Mr Dudley was arranged. The previous matches had been played in private, but this took place in compliance with the wish of the Lexington players, and was played in public. It excited considerable interest. The play commenced on 29 March [1850] and terminated on 4 April, the score at the close being Mr Dudley 5, myself 11, drawn 3. These games are the best I remember playing in America, and would be well worth recording; but I have not a note of one of them. Mr Dudley bore his defeat well, and in the most handsome manner, declared himself fairly beaten.”

Source: the article by Löwenthal entitled “Löwenthal’s Visit to America” on pages 392-393 of the New York, 1857 tournament book.’

Mr Bauzá Mercére has also submitted these games from the

American Chess Magazine, 1847:

Pages 13-14:

Edward A. Dudley – Mr B.Frankfort, KY, 1846

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 d6 5 d4 exd4 6 cxd4 Bb6 7 h3 h6 8 Nc3 Nf6 9 O-O O-O 10 a3 a6 11 Qd3 Na5 12 Ba2 Nh7 13 b4 Nc6 14 Bb2 Kh8 15 Nd5 Ba7 16 Rac1 Be6 17 Bb1 f5

18 Nf4 fxe4 19 Ng6+ Kg8 20 Qxe4 Re8 21 Ne7+ Qxe7 22 Qxh7+ Kf8 23 Bg6 Bg8 24 Qh8 Red8 25 d5 Ne5 26 Nxe5 dxe5 27 Kh1 Rxd5 28 Bb1 c6 29 f4 e4 30 Bxe4 Rd2 31 Rce1 Rf2 32 f5 Rd8 33 f6 Rxf1+ 34 Rxf1 Ke8 35 Bg6+ and White won.

Pages 103-104:

Edward A. Dudley – Mr B.Frankfort, KY, 1847

Scotch Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Bb4+ 5 c3 dxc3 6 O-O cxb2 7 Bxb2 Bf8 8 Qb3 Qe7 9 Ba3 d6 10 Nc3 Be6 11 Bxe6 Rb8 12 Nd5 Qd8 13 Bxf7+ Kxf7 14 Nxc7+ Kg6 15 Qe6+ Qf6 16 Qg4+ Kh6 17 Bc1+ g5 18 Bxg5+ and White won.

Pages 155-156:

Benjamin I. Raphael – Edward A. DudleyMatch, Louisville, 1847

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 e5 5 Nxc6 bxc6 6 Bc4 Bc5 7 O-O Ne7 8 Kh1 O-O 9 f4 d5 10 Bd3 f5 11 fxe5 fxe4 12 Be2 Nf5 13 Bf4 Qe7 14 g4 Ne3 15 Bxe3 Rxf1+ 16 Qxf1 Bxe3 17 c3 Qxe5 18 Na3 Be6 19 Nc2 Rf8 20 Qxf8+ Kxf8 21 Nxe3 c5 22 Rf1+ Kg8 23 Kg2 g6 24 h4 Kg7 25 h5 d4 26 cxd4 cxd4 27 Nc4 Qc5 28 b4 Qxb4 29 Ne5 Qd2 30 Rf2 e3 31 h6+ Kxh6 32 g5+ Kg7 33 White resigns.

With this game, Dudley won the match +6 –5 =0.

Pages 264-265:

Edward A. Dudley – J. ShawBlue Lick, KY, August 1847

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 Qh4+ 4 Kf1 Nc6 5 d4 g5 6 Nc3 Nge7 7 Nf3 Qh5 8 d5 Na5 9 Qd4 Ng6 10 Nb5 Kd8 11 Bd2 Nxc4 12 Qxc4 Bd6 13 Bc3 Re8 14 Bf6+ Re7 15 Bxe7+ Kxe7 16 Nxc7 Rb8 17 Re1 g4

18 e5 Nxe5 19 Nxe5 Bxe5 20 d6+ Kf8 21 Qc5 f6 22 Qxa7 f3 23 Re3 Qf5 24 gxf3 gxf3 25 Qxb8 Qh3+ 26 Ke1 f2+ 27 Kxf2 Qh4+ 28 Ke2 Qg4+ 29 Ke1 Qh4+ 30 Kd1 Qd4+ 31 Rd3 Qg4+ 32 Kc1 Bxd6 33 Qxc8+ Kg7 34 Ne8+ Kh6 35 Nxd6 and White won.

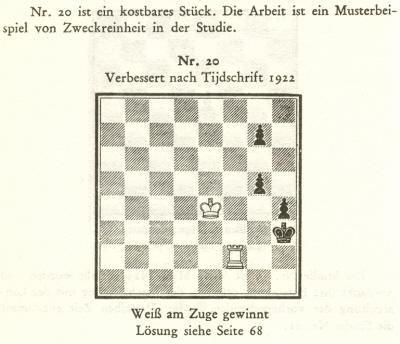

7316. Réti study (C.N. 7283)

From page 26 of Richard Réti: Sämtliche Studien (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1931):

Can this study be found in any year(s) of the Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond?

7317. Modern Chess Openings (C.N.s 7295 & 7300)

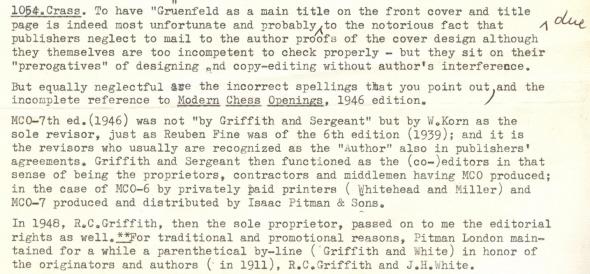

Below is the full text of C.N. 1054 (entitled ‘Crass’), written in 1985:

One book we most certainly shall not be reviewing in full is Grüenfeld Defense, Russian Variations by Eric Schiller, published by Chess Enterprises.

Grüenfeld is the novel spelling on the front cover. The back cover and spine prefer Gruenfeld. The Preface gives Grünfeld. The bibliography has Bruenfeld.

Ah yes, the bibliography, with its reference to the 1946 edition of Modern Chess Openings by ‘Griffith, P.C. & E.W. Sergeant’. P.C. Griffiths cannot be meant, since in 1946 he was not writing, he was being born. Presumably Mr Schiller was not sure whether the co-author was E.G. Sergeant or P.W. Sergeant, so he took one initial from each.

All this, though, is a mere antipasto, leading in to our tentative nomination for the most crass couple of sentences of 1985:

‘Dedication

To Harry Golombek, a friend and mentor, whose vast knowledge of chess, arbitin, and foreign languages I hop to someday acquire. May my writing retain its vitality as long as his has!’

As printed ...

In response, Walter Korn (San Mateo, CA, USA) wrote to us on 21 December 1985 (C.N. 1103):

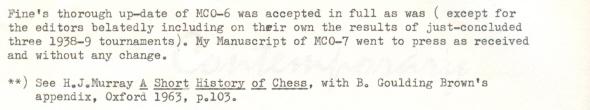

7318. McDonnell/MacDonnell

As remarked in the feature article Alexander McDonnell, no picture of him is known to exist. Even so (and although he died aged only 37, in the pre-photography era), the following appears in Worlds of Chess Champions, the booklet issued in 2003 by the Cleveland Public Library and mentioned in C.N.s 5149 and 5150:

It is not uncommon for Alexander McDonnell to be confused with George Alcock MacDonnell.

7319. Maurice Billecard (C.N.s 4798 & 7312)

Hassan Roger Sadeghi (Lausanne, Switzerland) notes a doctoral thesis by Maurice Billecard, Les Commissions rogatoires en droit international privé, published in Paris in 1902 and listed in the catalogue of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

7320. From the Philippines

This is the back cover of 64 Chess Games of Michail Tal (Makati, 1974). Do readers have information about any of the four books announced as ‘under preparation’?

7321. Modern Chess Openings (C.N.s 7295, 7300 & 7317)

Leonard Barden (London) writes:

‘The mild tone of Bob Wade’s August 1952 letter to CHESS which you reproduced in C.N. 7300 suggests that he had not completely given up on Walter Korn by then and that his hostility grew later.

Korn asked me to be the reviser for the tenth edition of Modern Chess Openings in 1962 or 1963, for a flat fee of about £1,000. Conscious of what Wade had told me, I haggled and asked for firm payment guarantees. The negotiations broke down, and Korn turned to Larry Evans. I should add that as an active grandmaster he did a better job than I, as a pure theoretician, would have done.

At the time when Korn was appointed editor of Modern Chess Openings, there was a widespread feeling among leading players and writers that his credentials (a few theoretical articles in the BCM) did not justify his acquiring the rights to Modern Chess Openings from the ageing Richard Griffith.’

7322. Hudson v Harrwitz

Pages 295-296 of the 1853 British Chess Review gave, courtesy of the Family Friend, a game ‘which Mr Harrwitz played a few days ago with one of our juvenile readers, probably the best player of his age in the world. The aptitude, nay ingenuity, developed for the game becomes truly astonishing when we consider that the boy is no more than eight and a half years old’.

Hudson – Daniel HarrwitzVenue (?), 1853

(Remove Black’s queen’s rook.)

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 e6 4 d5 Nce7 5 d6 Nc6 6 Bb5 Qa5+ 7 Nc3 Nd8 8 Bd2 Qb6 9 e5 f6 10 exf6 Nxf6 11 Be3 Bxd6 12 b4 a6 13 Ba4 Qxb4 14 Qd2 Nf7 15 Rb1 Qa5 16 O-O b5 17 Bxb5 axb5 18 Rxb5 Qc7 19 Re1 O-O 20 h3 Bb7 21 Ng5 Nxg5 22 Bxg5 Bc6

23 Bxf6 Rxf6 24 Rd1 Bf4 25 Qe2 Rg6 26 f3 Be5 27 Rxc5 d6 28 Rc4 d5 29 Rg4 Bxc3 30 Rxg6 hxg6 31 Qxe6+ Kh7 32 Rd3 Bf6 33 h4 Bxh4 34 Rc3 Qa7+ 35 Kh1 Bd7 36 Qxd5 Bg3

37 f4 Bxf4 38 Rf3 Bh6 39 Rf7 Bc6 40 Rxa7 Bxd5 41 a4 Be3 42 Re7 Bf2 ‘and, after some 15 more moves, the game was drawn’.

7323. Botvinnik’s family

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) shares three photographs from his collection. Information on the reverse side suggests that they were taken during the Groningen, 1946 tournament.

7324. Maurice Billecard (C.N.s 4798, 7312 & 7319)

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) mentions that his website includes a page on Maurice Billecard. Our correspondent notes, in particular, that at the time of the Ostend, 1907 tournament Billecard was working as a judge in Cherchell, a town 90 kilometres from Algiers.

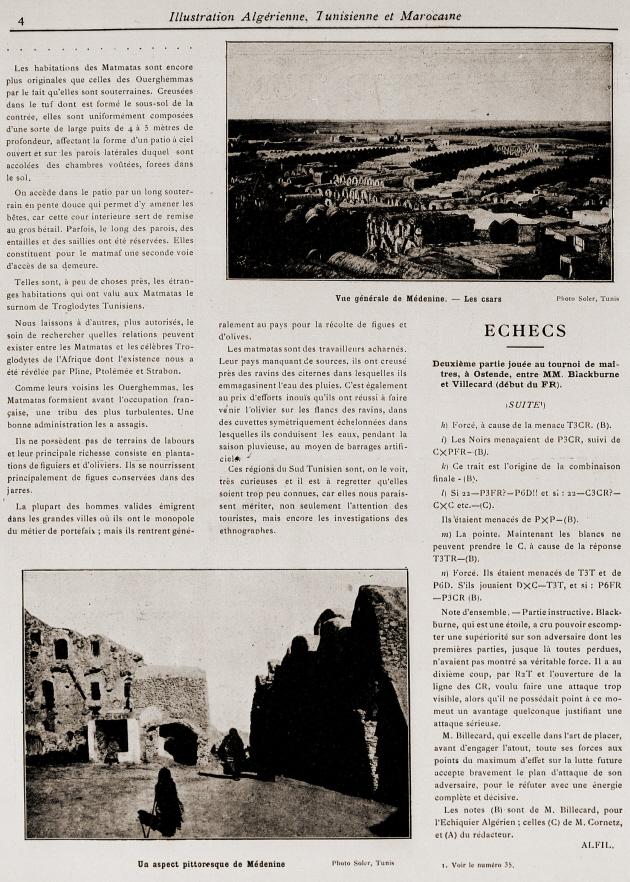

In the Ostend tournament Billecard defeated, among others, Blackburne, Mieses, Swiderski and Teichmann, and he annotated a number of his wins in Illustration Algérienne, Tunisienne et Marocaine. We are grateful to Mr Thimognier for the pages (27 July 1907, page viii, and 3 August 1907, page 4) which had Blackburne v Billecard, given that only the first 28 moves were in the tournament book (pages 260-261).

Joseph Henry Blackburne – Maurice Billecard

Ostend, 1907

Bishop’s Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nc6 3 d3 Nf6 4 Nf3 Bc5 5 Be3 Bb6 6 Nc3 d6 7 O-O Bg4 8 Bb5 O-O 9 h3 Bh5 10 Kh2 Nd4 11 Bxd4 exd4 12 Ne2 c6 13 Ba4 Bxf3 14 gxf3 Nh5 15 Rg1 Qh4 16 Qf1 f5 17 Bb3+ Kh8 18 Qg2 Rf6 19 f4 fxe4 20 dxe4 Raf8 21 f5

21...d5 22 Qg4 Qxf2+ 23 Rg2 Bc7+ 24 Kh1 Qe3 25 Rf1 dxe4 26 Nxd4 Ng3+ 27 Rxg3 Qxg3 28 Qxg3 Bxg3 29 Kg2 Be5 30 Ne6 Re8 31 Ng5 g6 32 Be6 gxf5 33 Nf7+ Kg7 34 Nxe5 Rexe6 35 Nc4 f4 36 a4 b5 37 axb5 cxb5 38 Na3 a6 39 c3 f3+ 40 Kh1 e3 41 White resigns.

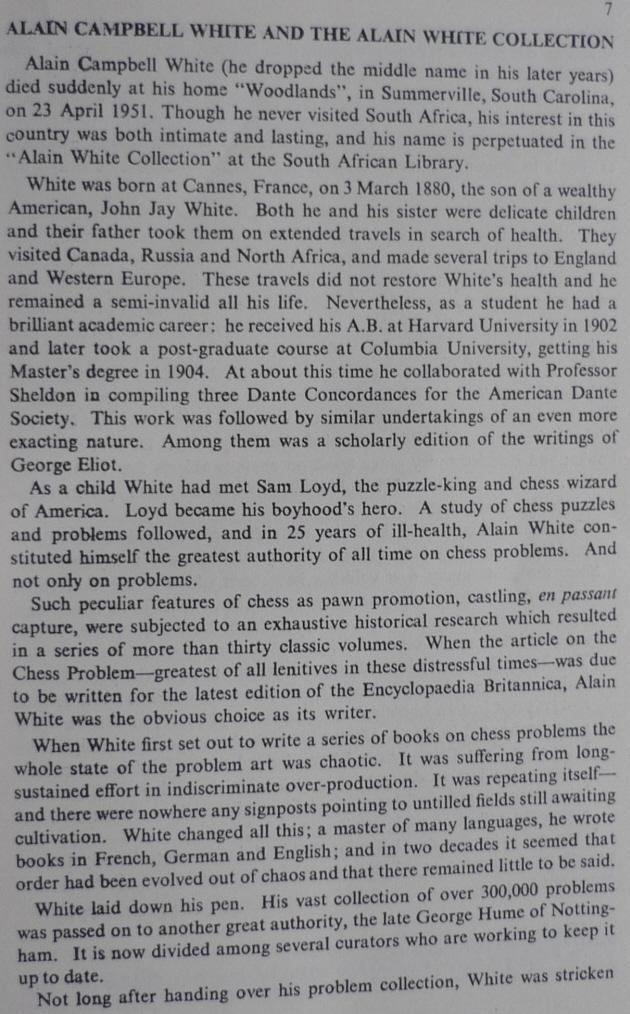

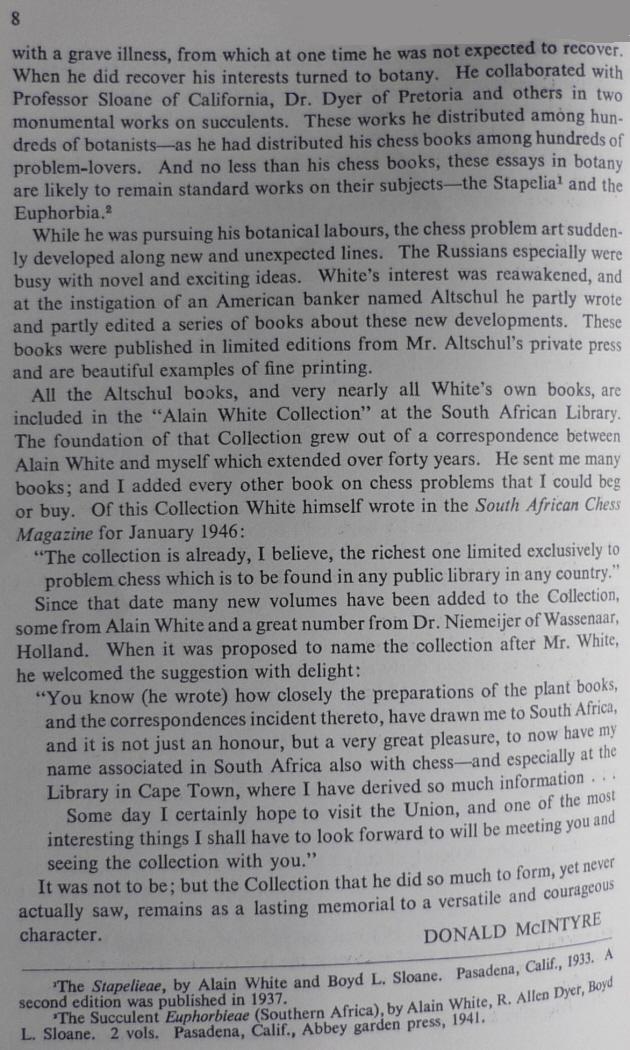

7325. Alain White Collection (C.N.s 6678 & 6703)

From Manfred Mittelbach (Hamburg, Germany) comes this article by Donald McIntyre in the Quarterly Bulletin of the South African Library, September 1951, pages 7-8:

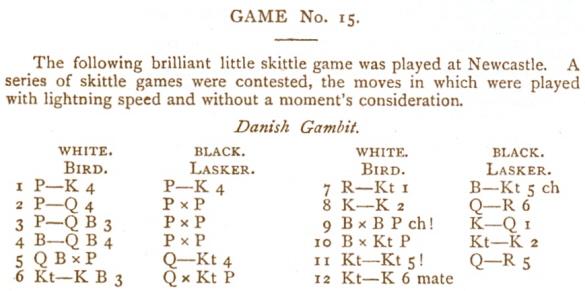

7326. Bird v Lasker

Kevin Harrison (Hunters Hill, NSW, Australia) asks about

the authenticity of the Danish Gambit miniature H.E. Bird

v Emanuel Lasker, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 1892: 1 e4 e5 2 d4

exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Bc4 cxb2 5 Bxb2 Qg5 6 Nf3 Qxg2 7 Rg1 Bb4+

8 Ke2 Qh3 9 Bxf7+ Kd8 10 Bxg7 Ne7 11 Ng5 Qh4 12 Ne6 mate.

We have no reason to doubt it. The game was published on page 48 of the October 1892 issue of N.T. Miniati’s Chess Review:

7327. Jakob/Jacques Mieses (C.N. 7313)

From Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel):

‘Jewish men are usually given a “Jewish” (i.e. Hebrew) name during their bris (circumcision). Mieses’ name was יעקב (“Ya’akov”). Jakob and Jacques are the most common German and French, respectively, versions of that name. If using “Jacques” instead of “Jakob” , Mieses is unlikely to have considered that he was changing his (Hebrew) name at all; it was simply a different version of the same name. “Jacques” may well have been used because French was (still) the international language when Mieses started playing in international tournaments.

Incidentally, the Hebrew יעקב is used interchangeably with ז'אק (Jacques) in Hebrew-language sources. For example, in Moshe Czerniak’s Ha’sachamat (page 2 of volume one, number one, and merely dated “1936”) it was remarked that “one of the relics of the great players of the nineteenth century, Ya’akov Mieses (יעקב מיזס), was in our country”. However, the same Czerniak wrote in 64 Mishbatzot (March-April 1957, page 215) about “Jacques Mieses” (ז'אק מיזס) when recalling the same visit.’

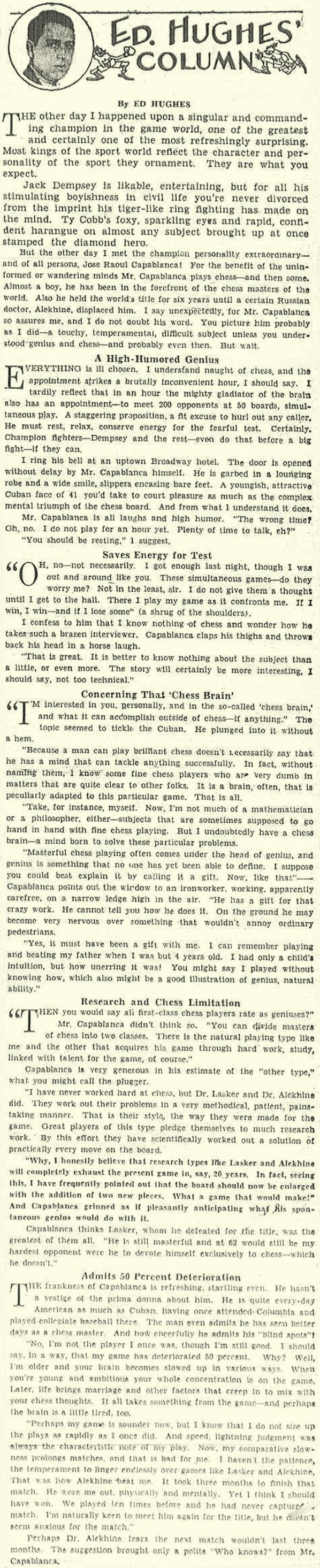

7328. MacDonnell on Steinitz

After criticizing Steinitz’s prose style, G.A. MacDonnell deployed on page 39 of The Knights and Kings of Chess (London, 1894) a word which we have not seen elsewhere:

‘He is a terrible poluphloisboioist.’

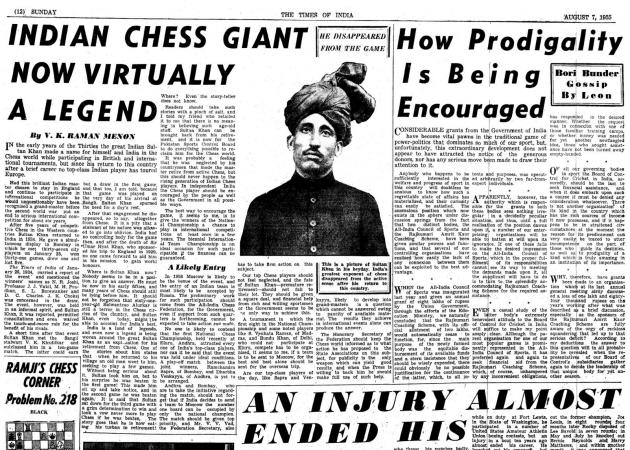

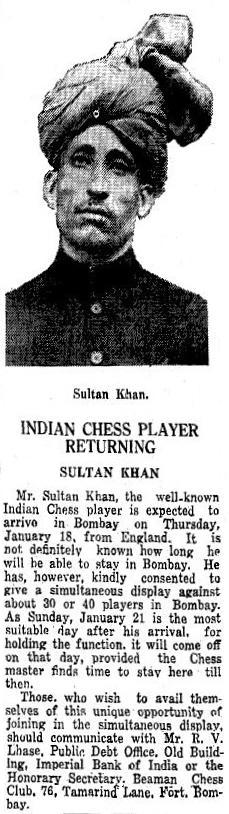

7329. Sultan Khan

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) sends an article from page 12 of The Times of India, 7 August 1955:

Our correspondent notes that the same photograph had been used on page 12 of the 15 January 1934 issue of the newspaper:

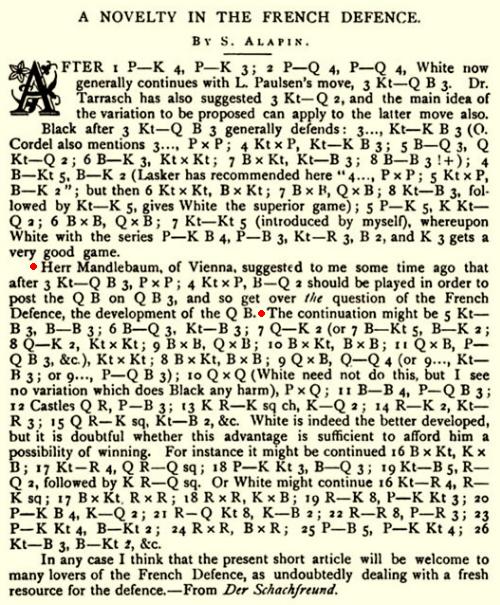

7330. Fort Knox Variation

A further contribution from Mr Urcan concerns the so-called ‘Fort Knox Variation’ (1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Bd7). Who gave it that name, and when?

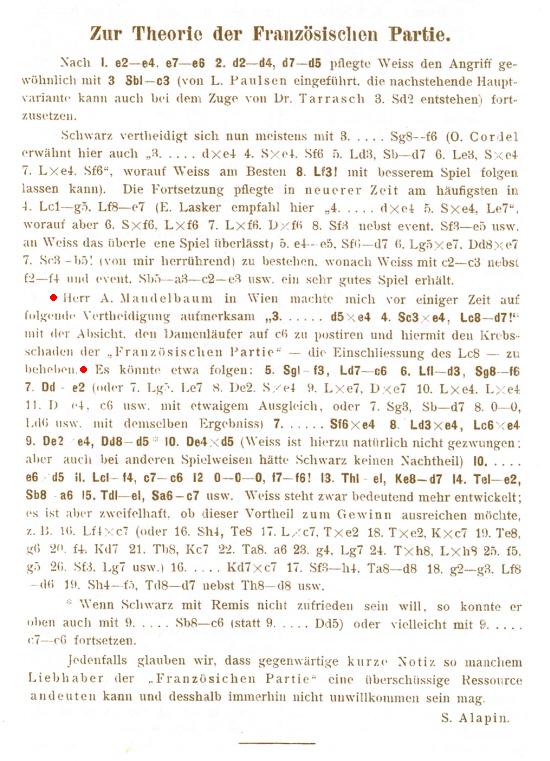

The above feature on page 471 of the November 1899 BCM has also been submitted by Mr Urcan, and we add Alapin’s original article (with the correct spelling Mandelbaum) on page 117 of Der Schachfreund, October 1899:

7331. Magazine grumbles

An article by G.H. Diggle in the November 1983 Newsflash which was reproduced on pages 104-105 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘Some time ago the BM, having inveigled the unsuspecting Editor of “a well-known chess periodical” into having lunch with him, proceeded to inform him how to conduct his magazine. Throughout the soup and fish he reviled algebraic notation; and when the middle-game was reached in the form of roast beef he launched a choleric attack on the space devoted to “these wretched foreign grandmaster tournaments. What do these tedious tabulated results, full of hideous names all consonants and no vowels, convey to me or anyone else? I would rather plough through a pedigree in Genesis. In the good old days when there were only about 20 great masters, one could find one’s way around the Chess World, and knew whom to expect to see playing – Capablanca, Alekhine, Rubinstein, Janowsky – real flesh and blood struggling for first place. But what is a tournament now but a sleepy chess factory churning out half-points – the foreman (or Controller) daren’t say anything – if he were to suddenly pipe up: ‘Here, you two with bishops of opposite colours, put a jerk in it and perhaps we shall see some result!’, he would be met with the riposte: ‘Result? You must be joking! We only want half each for our grandmaster norm!’ Moreover, some of the published games take up enormous space, yet when examined are found to consist in reality of only one move, always somewhere in the middle. The first 25 are all book, then White produces some new ‘thunderbolt’ – or damp squib – which he has smuggled under his shirt all the way to the tournament. This awakens Black, who turns green with fright and takes two hours over his reply, and the rest is all time-scramble and blunders. Why devote oceans of space to this rubbish? What about some lengthy historical articles or some good Obituaries instead? Men who have given long service to chess both as players and officials are often shovelled into the grave with such lean epitaphs as ‘Much missed’, ‘Never made an enemy’ or (if he was obviously a nasty fellow) ‘Beneath a brusque exterior beat the kindliest of hearts’”.

“My dear Badmaster”, replied the Editor when that worthy had at last shut up during the coffee stage, “Nothing could give us greater pleasure (sad pleasure, I need not add) than to honour adequately the chess departed. But you seem quite unconscious of the practical difficulties. Chessplayers seldom die at a considerate time or in a convenient place. Some make a habit of expiring just after we have gone to press, and you will appreciate that they never give us prior notice of the event. In fact, the first we hear of it and the first pangs of grief we suffer usually occur months afterwards when their annual subscription to our magazine fails to arrive. All chessplayers are not prudent patriarchs like yourself, who I have no doubt have already composed a glowing self-obituary (with fictitious initials at the end) and instructed your executors on your demise to forward copies instantly to all chess periodicals, especially 64, Chess Review and Shakhmatny Byulletin. An Obituary is, and always has been, a toss-up. A player may drop out of the game for 30 years and perish on a desert island. Even if a member of a Club has a fatal heart attack in the middle of a game, who is to be found to do a This is Your Life? As like as not, his clubmates will know incredibly little about him when it comes to the point – someone may remember that he sometimes played the Queen’s Gambit, and the Treasurer that he never paid his sub till the third application. As to your curious ideas about modern tournaments, I am afraid you are hopelessly out of touch – your antennae have become antediluvian ...”

BM: “Antediluvian antennae? Has it come to this? All right, I resign!”’

7332. Bird v Lasker (C.N. 7326)

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) notes that the Bird v Lasker lightning game was also published on page 7 of the Leeds Mercury, 24 September 1892, introduced by this paragraph:

‘The following brilliant skirmish was played at the County Hotel, Newcastle, on the occasion of the presentation of the “Newcastle Chronicle Chess Trophy”. It is only fair to state that about a dozen games were rattled off in the space of two hours, and of these Herr Lasker won the majority. He made the remark afterwards that his arm, not his head, ached; such was the rapidity of the moves and the large amount of woodshifting.’

7333.

Poluphloisboioist (C.N. 7328)

From Robert Sherwood (E. Dummerston, VT, USA):

‘The word means “loud-roarer” (Liddell and Scott lexicon) in Classical Greek; -ist has been added to the adjective poluphloisbos. The latter word is attested in line 34 in the Greek text of Book I of the Iliad and refers to the (Aegean) sea that Chryses walks beside after being harshly sent away by Agamemnon.’

7334. 1 d4 d5 2 e3

Annotating a correspondence game between two amateurs, Tartakower described 1 d4 d5 2 e3 as the Biscay Opening (‘which is really more aggressive than it is believed to be’).

Source: Chess Review, June 1939, pages 138-140, the notes having originally appeared in La Stratégie. What is the basis or justification for ‘Biscay Opening’?

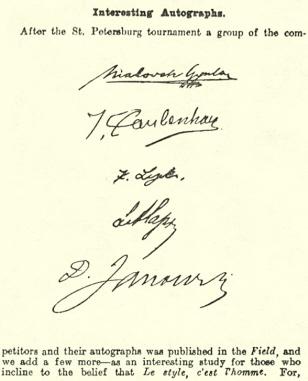

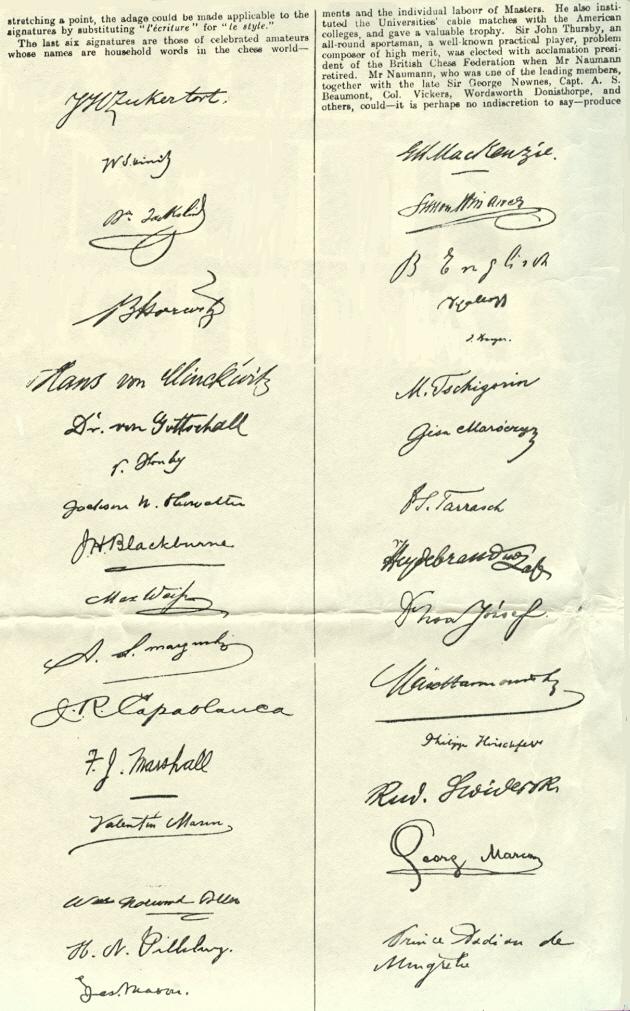

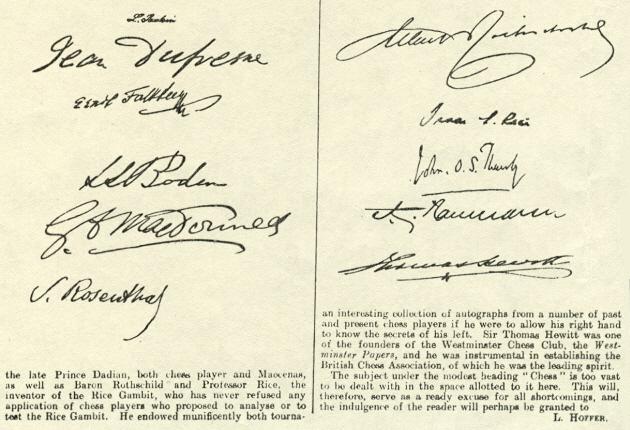

7335. Autographs

Elmer Sangalang (Manila, the Philippines) requests a compilation of autographs of prominent chess figures.

The item below is reproduced from pages 1281-1282 of The Field, 31 December 1910, and it begins our new feature article, Chess Autographs.

7336. Schaken

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) mentions that many chess

photographs can be viewed at the

‘Memory of the Netherlands’ website by entering

either the Dutch word for chess, Schaken, or the

names of such players as Lasker, Marshal [sic],

Capablanca, Aljechin, Euwe, Botwinnik, Keres, Larsen and

Tal.

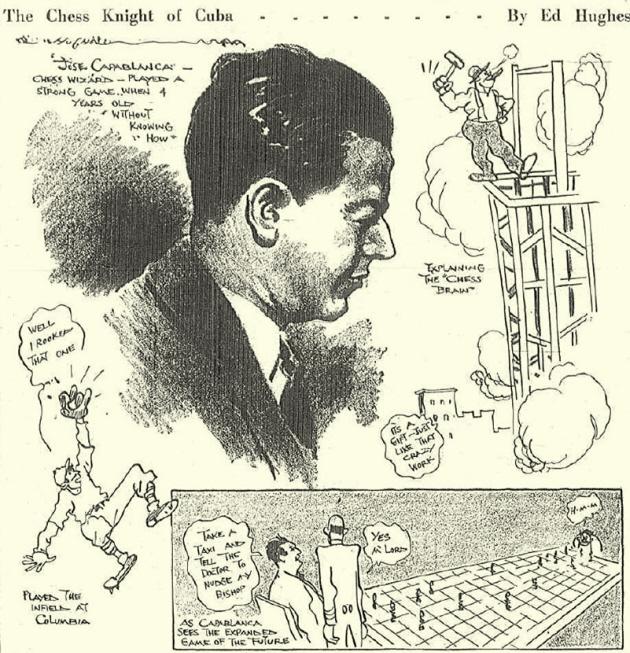

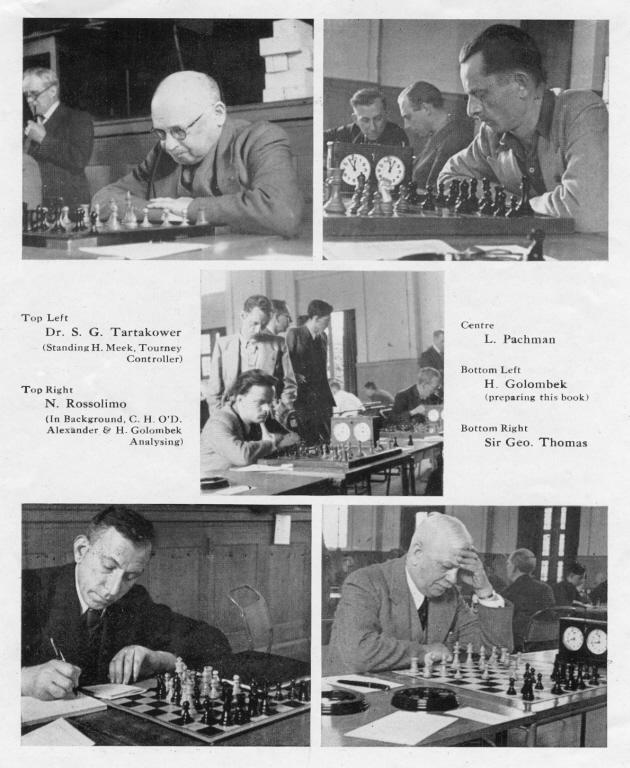

7337. Interview with Capablanca in 1931

Mr Urcan also points out an interview with Capablanca conducted by Ed Hughes and published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 18 February 1931, page 24:

7338. Poluphloisboioist (C.N.s 7328 & 7333)

From Michael Syngros (Amarousion, Greece):

‘The term poluphloisboioist consists of two words united into one: “Πολυ” and “φλοισβος”. “Πολυ” means much/more than usual/continuous. “Φλοισβος” is the soft noise which a low wave makes when it arrives and ends at the beach. It is rather like the sound “ffflllsss, ffflllsss, ffflllsss” (the first three consonants of the word “φλοισβος”). In a sense, it is a low (soft) repeated noise which means nothing, and I believe that it is in this sense that MacDonnell used the Hellenic word.

I do not know on what basis any English dictionary transliterated the Hellenic word as “poluphloisboioist”. In my view, it should be transliterated as “polyfloisvosist” (the “y”, “oi” and “i” are all pronounced like the “i” in the English word “this”). It is certainly true that the ending -ist is an English-language one.

Nor can I understand why the word was translated as “loud-roarer”, and particularly since “φλοισβος” denotes a soft, not loud, noise.’

Below are pages 38-39 of G.A. MacDonnell’s The Knights and Kings of Chess (London, 1894):

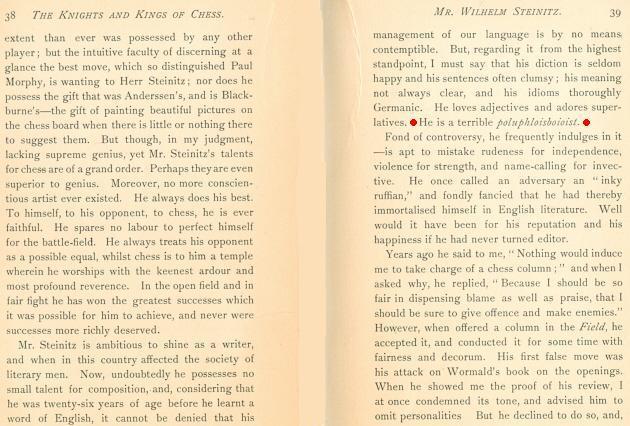

7339. Southsea, 1949

The frontispiece of the booklet Southsea Chess Tournament 1949 by H. Golombek (Birmingham, 1949):

7340. 1 d4 d5 2 e3 (C.N. 7334)

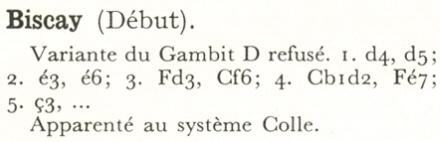

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) notes that the entry regarding Pierre Biscay on page 39 of the Dictionnaire des échecs by F. Le Lionnais and E. Maget (Paris, 1967) is followed by this brief item on the next page:

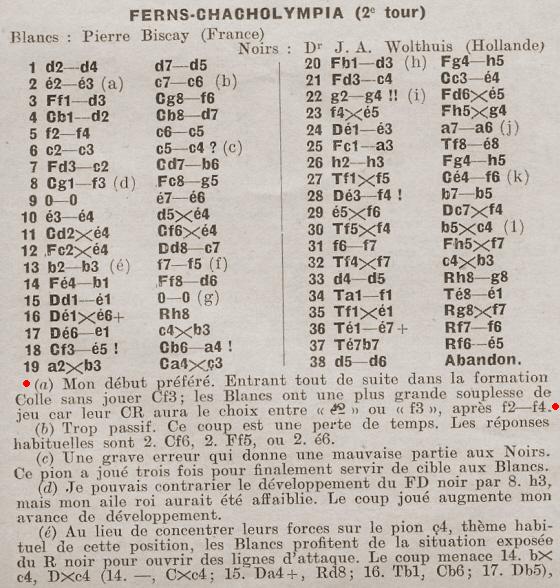

Our correspondent supplies a game annotated by Biscay, from pages 11-12 of the May 1938 issue of the Bulletin de la Fédération Française des Echecs:

Pierre Biscay – J.A. Wolthuis

Correspondence (Final B of the Olympiad of the

Internationaler Fernschachbund, 1937)

Queen’s Pawn Opening

1 d4 d5 2 e3 c6 3 Bd3 Nf6 4 Nd2 Nbd7 5 f4 c5 6 c3 c4 7 Bc2 Nb6 8 Ngf3 Bg4 9 O-O e6 10 e4 dxe4 11 Nxe4 Nxe4 12 Bxe4 Qc7 13 b3 f5 14 Bb1 Bd6 15 Qe1 O-O 16 Qxe6+ Kh8 17 Qe1 cxb3 18 Ne5 Na4 19 axb3 Nxc3 20 Bd3 Bh5 21 Bc4 Ne4

22 g4 Bxe5 23 fxe5 Bxg4 24 Qe3 a6 25 Ba3 Rfe8 26 h3 Bh5 27 Rxf5 Nf6 28 Qf4 b5 29 exf6 Qxf4 30 Rxf4 bxc4 31 f7 Bxf7 32 Rxf7 cxb3 33 d5 Kg8 34 Raf1 Re1 35 Rxe1 Kxf7 36 Re7+ Kf6 37 Rb7 Ke5 38 d6 Resigns.

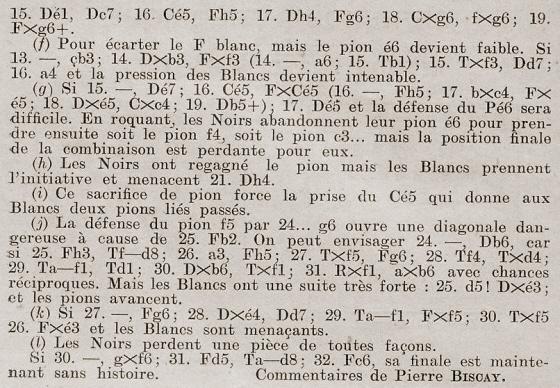

The above photograph comes from the set ‘Le Monde des Echecs’ produced by L’Echiquier. It also appeared opposite page 8 of the 2 March 1933 issue of that magazine. For biographical information, see Mr Thimognier’s page on Biscay.

| First column | << previous | Archives [87] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.