Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [121] | next >> | Current column |

8756. Chess Olympiads

Chess Review, December 1937, page 277

Most of the Olympiads (‘International Team Tournaments’) in the 1930s had a busier schedule than is the case nowadays, and the present item takes Warsaw, 1935 and Stockholm, 1937 as examples.

On page 38 of The Best Games of C.H.O’D. Alexander by Harry Golombek and Bill Hartston (Oxford, 1976) Golombek wrote regarding Warsaw, 1935:

‘This Olympiad stands out in my memory as the most exhausting event in which I ever played. The schedule was a crowded one in which, on a number of days, we had to play two rounds in one day.’

From William Winter’s memoirs on pages 166-167 of CHESS, 9 March 1963, also concerning the Warsaw Olympiad:

‘The tournament itself was one of the hardest I have ever played in. Not only were there more teams than ever before, but they were very much stronger. Apart from the Russians, who were not at that time members of the International Federation, and Lasker and Capablanca, there was hardly a grandmaster in the world who was not representing his country. Alekhine played for France, and I had to meet him in the evening, after struggling for six hours with Ståhlberg. I don’t know how I managed to make a draw. I think it must have been my subconscious mind which guided the pieces. Two games a day against such opposition is sheer cruelty, and much as I love playing chess against great masters I was heartily glad when the event was over.’

The records indicate that his games against Ståhlberg and Alekhine were played in rounds two and five, on 17 and 19 August 1935 respectively. See, for instance, pages 24 and 27 of VI Wszechświatowa Olimpiada Szachowa, Warszawa 1935 by Mirosława Litmanowicz (Warsaw, 1996). The full Ståhlberg v Winter game may not have survived, but, as Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) has pointed out to us, the first 22 moves are available from page 17 of Ståhlberg’s book El gambito de dama (Buenos Aires, 1942).

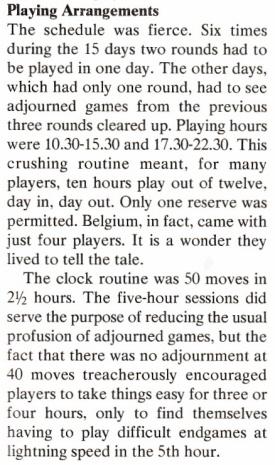

‘The schedule was fierce’ at Stockholm, 1937 too, as noted on page 7 of W.H. Cozens’ posthumous book The Lost Olympiad (St Leonards on Sea, 1985):

The time-limit, though not the schedule, was welcomed by the American Chess Bulletin (July-August 1937 issue, page 66):

‘On alternate days two rounds of matches were contested, and these with the sessions for adjourned games (after every spell of three rounds) taxed the endurance of most of the participants to the utmost. Playing rules called for 50 moves in 2½ hours – a heathly innovation and an improvement over the slower and more enervating time-limits favored in the past.’

In a report on the Stockholm event on pages 16-17 of CHESS, 14 September 1937 Harry Golombek wrote:

‘The pace is cracking: three games every two days; adjournments galore.’

A further observation by Golombek:

‘Striking, too, is the different attitude adopted by the chessplayer according to his nationality; his temperament or the position of his game. Flohr, for instance, has a care-worn expression whatever his position. Ståhlberg always seems overwhelmed by a calm melancholy. The Americans wear a peaceful, assured expression; here the consciousness of power is very evident. They, and everybody else, realize the US have sent to Stockholm the strongest team that has ever played in an international team tourney.’

He also discussed the playing conditions in Stockholm:

‘What strikes an habitué of London, Hastings or Margate most of all is the prevailing hum of by no means light conversation. Silence is not strictly enforced by any means. The sound is a strange polyglot blend composed of about 18 languages. Through the mixture there runs a prevailing strand of Swedish underlying which is a subordinate texture of German (for German is the lingua franca of the international chessplayer). Noise does not seem to disturb the players, most of whom could apparently play on unaffected in an aerodrome with 50 aero-engines going all out ...

... The spectators walk round the sides of the room which have naturally been carpeted to prevent noise. The number of these spectators has been very large, for chess is very popular in Sweden; over 10,000 paid to come in during the first week.’

Euwe and Ståhlberg, Stockholm, 1937 (CHESS, 14 October 1937, page 61)

Much has changed since the 1930s, but commentators’ love of trivia is perpetual. The present jottings end with an extract from page 228 of the October 1935 Chess Review:

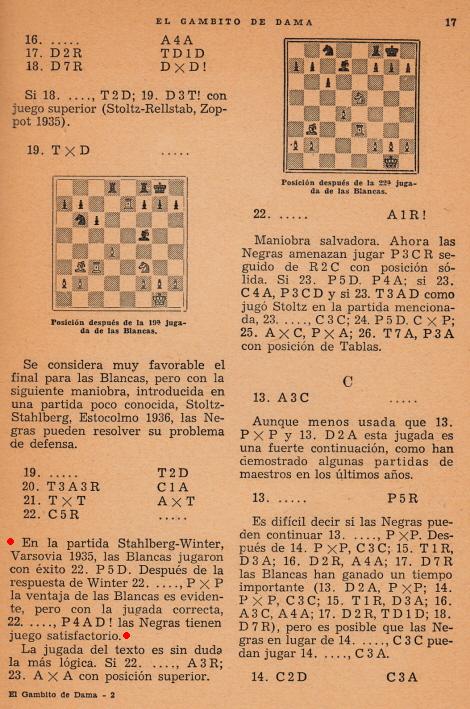

8757. El gambito de dama

The page from El gambito de dama by G. Ståhlberg (Buenos Aires, 1942) which was mentioned in C.N. 8756:

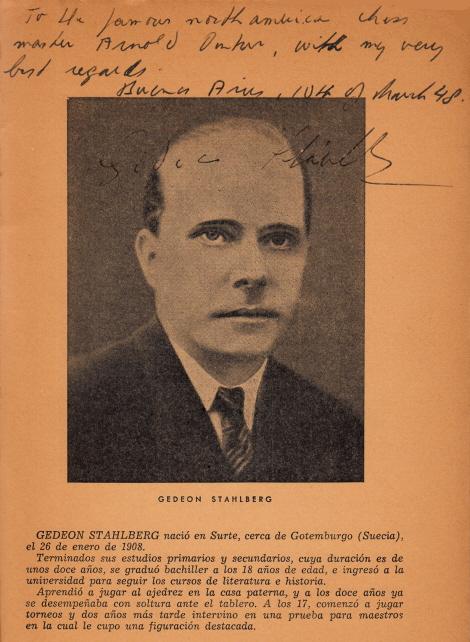

Our copy of the book was inscribed by Ståhlberg to Arnold Denker:

8758. Folkestone Olympiad, 1933

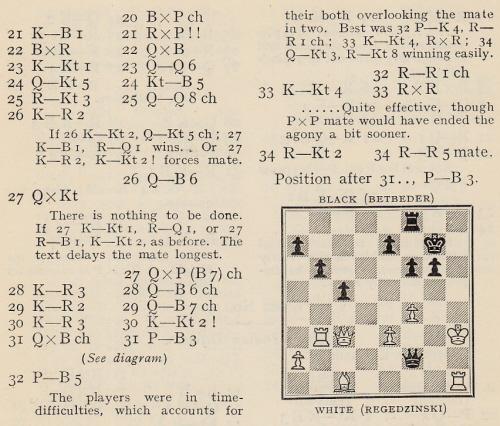

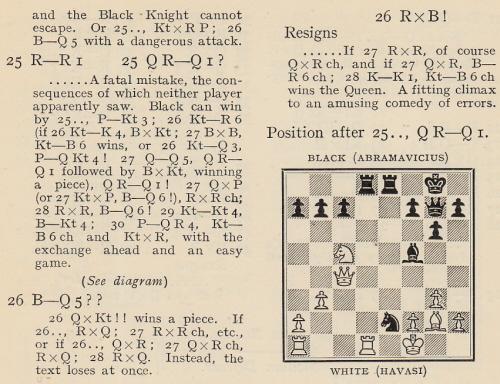

Three snippets from the tournament book:

1) Teodor Regedziński (Poland) – Louis Betbeder Matibet (France), round two, 13 June 1933:

2) Kornél Havasi (Hungary) – Leonardas Abramavičius (Lithuania), round five, 15 June 1933:

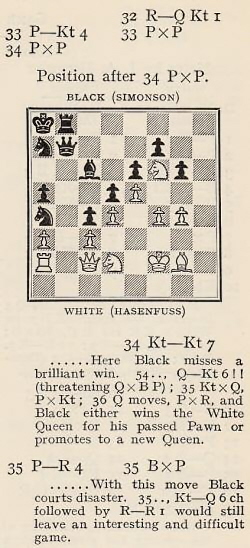

3) Wolfgang R. Hasenfuss (Latvia) – Albert C. Simonson (USA), round six, 16 June 1933:

Source: Book of the Folkestone 1933 International Chess Team Tournament (Leeds, 1933), pages 19, 51 and 55. The title page states: ‘The Principal Games annotated by I. Kashdan and other Masters’. The first two games above were annotated by Kashdan, the third by Al Horowitz.

8759. N.N.

Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) asks whether the meaning and origin of the term ‘N.N.’ have been established. Is there, for instance, any basis for the claim that it stands for ‘no name’?

We have never seen a definitive explanation, but it is the kind of matter which lends itself to theories prefaced by unhelpful phrases like ‘my understanding has always been that ...’

From the correspondence section on page 92 of CHESS, February 1953:

‘That Numbskull N.N.

W.H. Cozens, Ilminster, asks, “What is the exact meaning of the German abbreviation ‘N.N.’ to denote an anonymous player?”

We don’t know; who does, please? – Ed.’

Page 110 of the March 1953 issue had a reply dated 28 January 1953 from Professor H.J. Rose of St Andrews:

‘N.N. should be written NN, with or without a stop after it according to taste. It stands for nomina, and therefore is not a German abbreviation but Latin, hence international. To double a one-letter abbreviation or the last letter of a longer one signifies the plural; thus COS is consul, but COSS consules (or some other case of the singular or plural respectively). It has long been customary to use NN for the given name and surname of an unknown person, as in the Anglican catechism, which has long misprinted it M in the answer to the first question, “What is your name?”. This in turn has given rise to silly interpretations of the misprint.’

The Editor of CHESS (B.H. Wood) commented:

‘But 17 people, from all over Europe, opined that “N.N.” stands for “nescio nomen” (“I don’t know the name”), one quoting Cassell’s dictionary to this effect. Some others suggest “notetur nomen” (“You may note the name”), “no nomen” and (the only German one) “nicht (ge)nannt”. No correspondent claimed to know who “N.N.” was.’

How far back can the usage be traced, in chess literature or more generally?

8760. A remark rarely heard

The final note to Foltys v Fine, Margate, 1937 on page 135 of Fine’s book Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958):

‘After this game my opponent made a remark rarely heard among chess masters. He said: “You play better than I do”.’

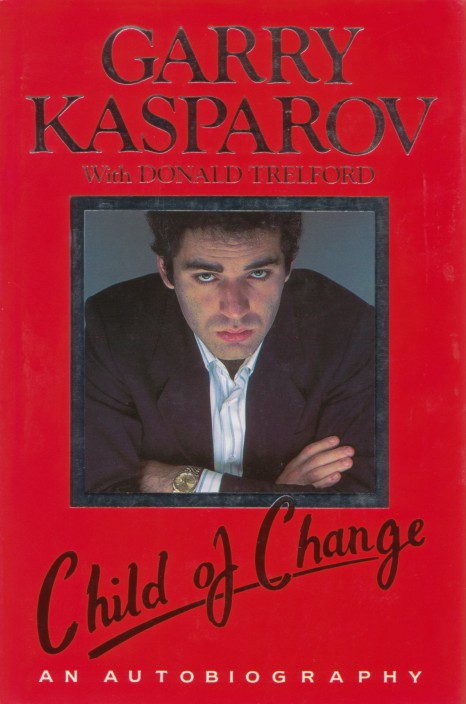

8761. Child of Change

A small addition just made to Cuttings prompts us to give here a few extracts from Tim Krabbé’s review of Child of Change by Garry Kasparov (London, 1987) on pages 60-62 of the 8/1987 New in Chess:

- ‘Something Karpov always failed to achieve during the 20 years of his public existence was managed by Kasparov in one stroke: inspire me with sympathy for Karpov. He did that with his recent autobiography Child of Change, which is an extreme example of unintentional self-defamation, and doubtlessly the reason that many hope Karpov will, for a change, become world champion again.’

- ‘... not only is Kasparov the youngest world champion in history, he is certainly also the most childish. He will tear his hair over this stupid autohagiography when he is 40!’

- ‘One sometimes laughs aloud reading a book. This book made me moan with disgust a few times. ... In all of the more than 200 pages of the book there is not one intelligent personal observation of the man [Karpov] he has faced hundreds of hours.’

- ‘The chessplayer’s occupational disease that no leaf can fall from a tree without being part of a conspiracy to make him lose is one thing, but here, without any proof, as Kasparov himself admits, the reputation of a colleague [Vladimirov] is murdered for the sake of a trashy pretext.’

- ‘What a waste of time, that book.’

- ‘How can a person drown so naively in his own ego?’

As noted in our article on the book, Kasparov subsequently acknowledged, ‘I deserved the critical reception of Child of Change’.

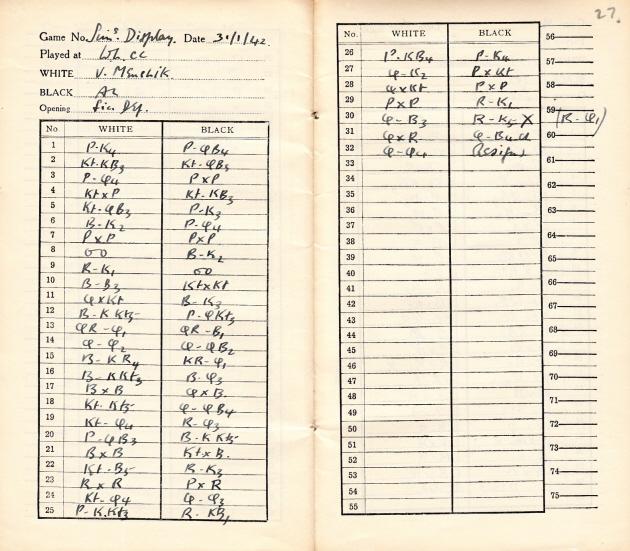

8762. Menchik v Laing

Another game from one of A.G. Laing’s score-books (C.N.

8728):

Vera Menchik – A.G. Laing

London, 31 January 1942

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 e6 6 Be2 d5 7 exd5 exd5 8 O-O Be7 9 Re1 O-O 10 Bf3 Nxd4 11 Qxd4 Be6 12 Bg5 b6 13 Rad1 Rc8 14 Qd2 Qc7 15 Bh4 Rfd8 16 Bg3 Bd6 17 Bxd6 Qxd6 18 Nb5 Qc5 19 Nd4 Rd6 20 c3 Bg4 21 Bxg4 Nxg4 22 Nf5 Re6 23 Rxe6 fxe6 24 Nd4 Qd6 25 g3 Rf8 26 f4

26...e5 27 Qe2 exd4 28 Qxg4 dxc3 29 bxc3 Re8 30 Qf3 Re4 31 Qxe4 Qc5+ 32 Qd4 Resigns.

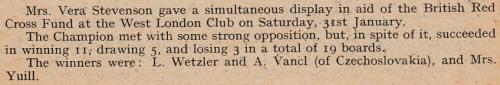

The display was referred to on page 55 of the March 1942 BCM:

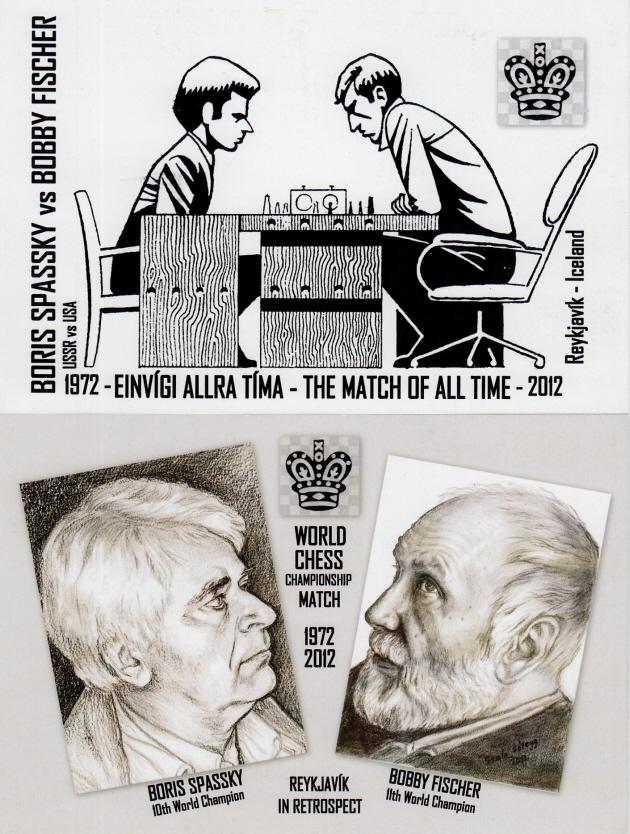

8763. 1972-2012

Two rare Icelandic postcards in our collection:

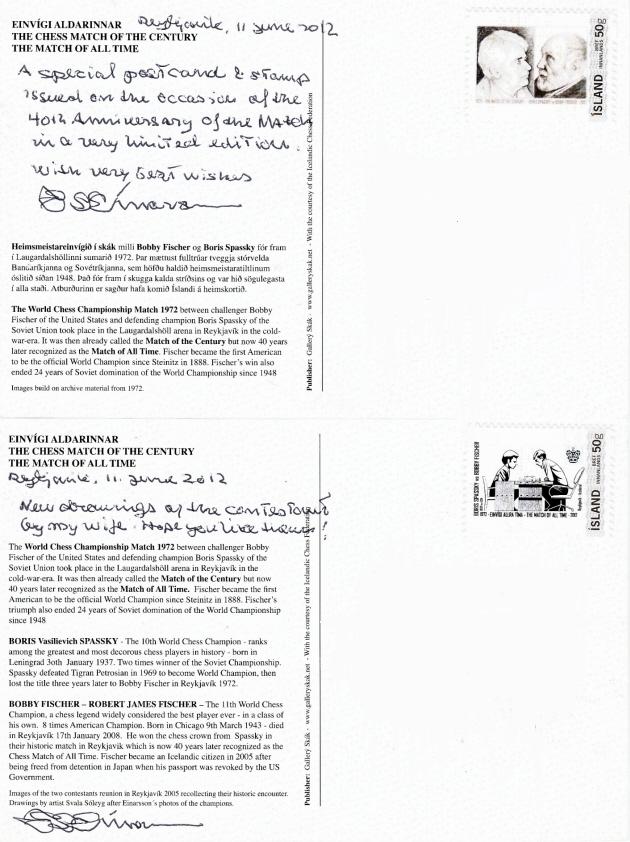

8764. Colle’s forename (C.N. 2382)

The text of C.N. 2382 (see page 348 of A Chess Omnibus):

On page 84 of the 2/2000 New in Chess there were two spellings of Colle’s forename, so which should it be? Although virtually all chess reference books put Edgar, almost all contemporary sources had Edgard. The latter was also the spelling on his gravestone (see page 37 of Histoire des maîtres belges by M. Wasnair and M. Jadoul). It was, moreover, the way he signed his name alongside the photograph in the booklet Le match Colle-Koltanowski, published in Brussels in 1926.

Does counter-evidence exist to explain why so many writers use the spelling Edgar?

8765. Marshall Chess Club

Frank Brady (New York, NY, USA) informs us that he has been commissioned to write an article on the history of the Marshall Chess Club, to mark its centenary in 2015. We shall be pleased to pass on to Dr Brady, who is President Emeritus of the Club, any messages from readers who can provide memorabilia, photographs, letters or other information.

Page 210 of the November 1915 American Chess Bulletin reported the founding of the Club, then known as ‘Marshall’s Chess Divan’, at 70 West Thirty-Sixth Street, New York, ‘just back of Herald Square and within a stone’s throw of one of the busiest sections of Broadway’.

8766. Rook

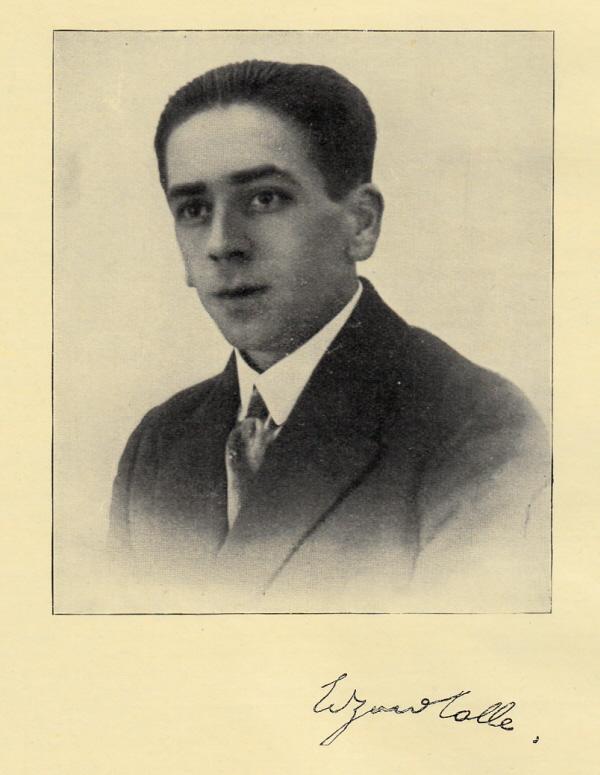

endings

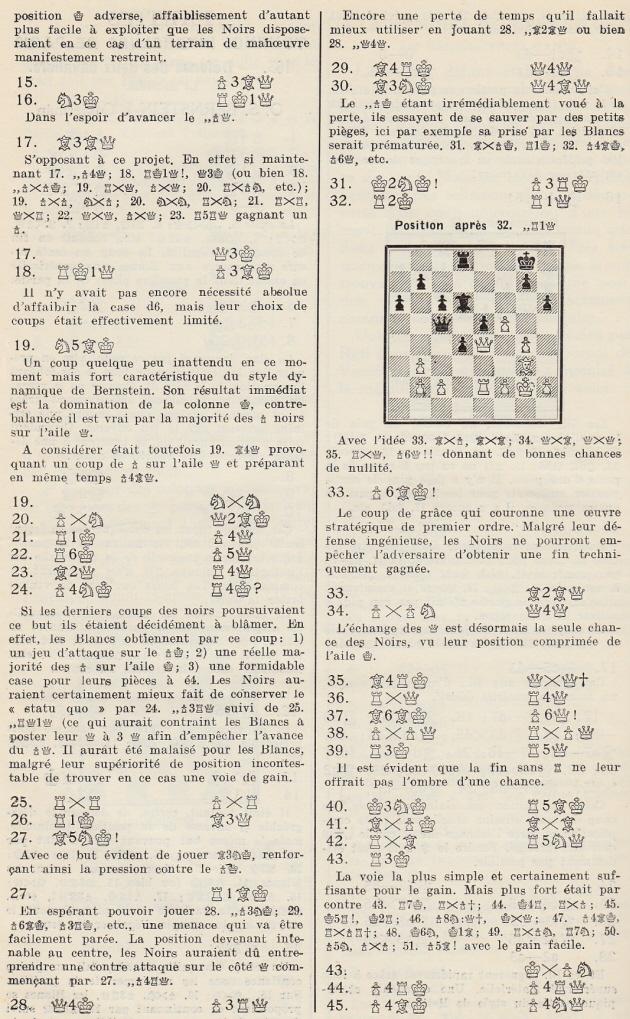

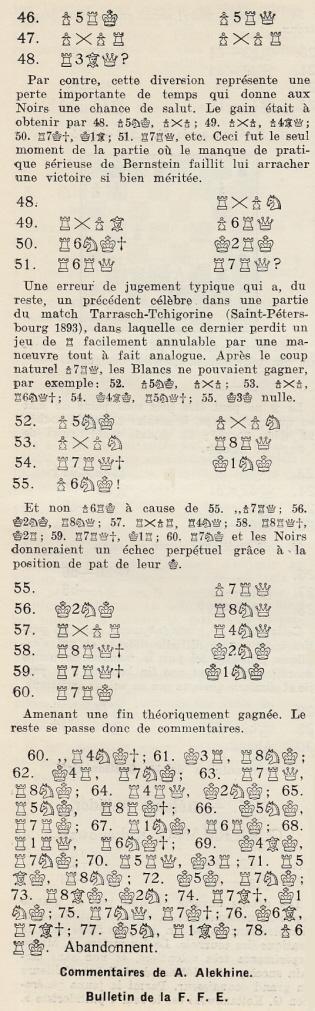

C.N. 3724 remarked that the Belgian magazine L’Echiquier sometimes employed an unusual form of the figurine notation. Below is the full game mentioned in that earlier item. It was given, with notes by Alekhine, on pages 339-341 of the August 1929 issue:

Ossip Samuel Bernstein – Josef Isaevich Cukierman

Two Knights’ Defence

Paris, 24 February 1929

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 d4 exd4 5 O-O d6 6 Nxd4 Be7 7 Nc3 O-O 8 Nde2 Be6 9 Bb3 Qd7 10 Nf4 Bxb3 11 axb3 Rfe8 12 Nfd5 Nxd5 13 Nxd5 Bf8 14 Qf3 Ne7 15 Bd2 c6 16 Ne3 Red8 17 Bc3 Qe6 18 Rfd1 f6 19 Nf5 Nxf5 20 exf5 Qf7 21 Re1 d5 22 Re6 d4 23 Bd2 Rd5 24 g4 Re5 25 Rxe5 fxe5 26 Re1 Bd6 27 Bg5 Rf8 28 Qe4 a6 29 Bh4 Qd5 30 Bg3 Qc5 31 Kg2 h6 32 Re2 Rd8 33 f6 Bc7 34 fxg7 Qd5 35 Bh4 Qxe4+ 36 Rxe4 Rd5 37 Bf6 d3 38 cxd3 Rxd3 39 Re3 Rd4 40 Kg3 Rf4 41 Bxe5 Bxe5 42 Rxe5 Rb4 43 Re3 Kxg7 44 h4 a5 45 f4 b5 46 h5 a4 47 bxa4 bxa4 48 Rc3 Rxb2 49 Rxc6 a3 50 Rg6+ Kh7 51 Ra6

51...Ra2 52 g5 hxg5 53 fxg5 Ra1 54 Ra7+ Kg8

55 g6 a2 56 Kg2 Rb1 57 Rxa2 Rb5 58 Ra8+ Kg7 59 Ra7+ Kg8 60 Rh7 Rg5+ 61 Kh3 Rg1 62 Kh4 Rg2 63 Ra7 Rg1 64 Ra4 Kg7 65 Rg4 Rh1+ 66 Kg5 Rh2 67 Rg1 Rh3 68 Ra1 Rg3+ 69 Kf4 Rg2 70 Ra5 Kh6 71 Rf5 Rg1 72 Ke5 Rg2 73 Rf8 Kg7 74 Rf7+ Kg8 75 Rb7 Re2+ 76 Kf6 Rf2+ 77 Kg5 Rf8 78 h6 Resigns.

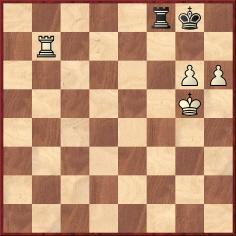

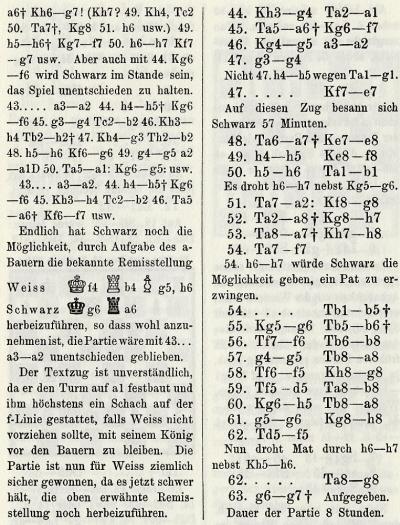

Alekhine’s reference at move 51 to Tarrasch and Chigorin concerns their ninth match-game. Below is an extract from pages 50-51 of Der Schachwettkampf zwischen Dr. S. Tarrasch und M. Tschigorin, Ende 1893 by Albert Heyde (Berlin, 1893):

The relevant part of Tarrasch’s Dreihundert Schachpartien (third edition, Gouda, 1925):

The Tarrasch v Chigorin ending has been widely discussed; see, for example, page 248 of volume five of Comprehensive Chess Endings by Yuri Averbakh and Nikolai Kopayev (Oxford, 1987), which mentioned analysis by Maizelis. The full game was annotated on pages 92-94 of the first Kasparov Predecessors book (London, 2003), with a reference at move 43 to Kling and Horwitz.

8767. Stephen Fry

Are any game-scores available featuring Stephen Fry?

One game which he played in public was in a simultaneous exhibition by Matthew Sadler in London on 2 July 1988 against ‘celebrity opponents’ (BCM, August 1988, page 355). There was also a brief report, with a photograph, on page 27 of the September 1988 CHESS.

8768. ‘Fair & Square’ (C.N. 8651)

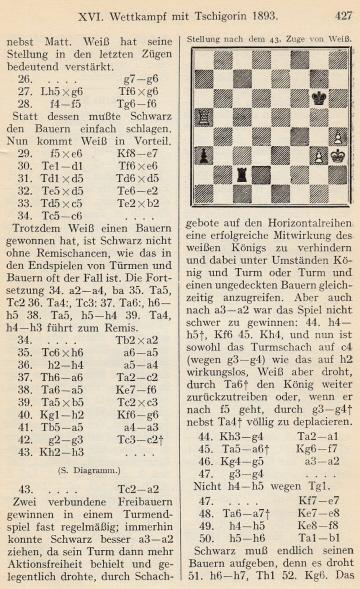

From page 75 of the 5/2014 New in Chess, in the lamentable ‘Fair & Square’ column:

What is known about this alleged remark of Capablanca’s, beyond its availability on a number of websites which document nothing?

8769. Who? (C.N. 7994)

Who is the player shown on the dust-jacket of Chess Ideas for Young Players by John Love and John Hodgkins (London, 1962)?

8770. David Pritchard on players and books

From Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA):

‘In the final chapter of The Right Way to Play Chess (New York, 1952) David Brine Pritchard makes the following observation:

“Chessplayers – and this must be whispered – are generally an egotistical, ill-mannered crowd. If they conformed to common rules of decorum these words would not have to be written.” (Page 224)

He then provides an example:

“I once carried out a private survey at a well-known chess restaurant where a large number of ‘friendly’ games are always in progress. In less than 30 per cent of those observed was resignation made with a good grace. In two-thirds of the games the loser either knocked his king over, abruptly pushed the pieces into the centre of the board, started to set up the men for a fresh game, or got up and walked away without saying a word to his opponent.” (Page 225)

Later, on the subject of chess literature he makes another interesting statement:

“Hundreds of books have been written on chess, and it is not intended that their respective merits shall be discussed here. In recent years there has been a tendency on the part of publishers to flood the market with game anthologies of a very mediocre standard. It is a great pity that so much inferior literature has been released, and it is strongly suggested that the student wishing to further his knowledge should be guided by the advices of an experienced player.” (Page 226)’

These comments were also in early editions of The Right Way to Play Chess published in the United Kingdom.

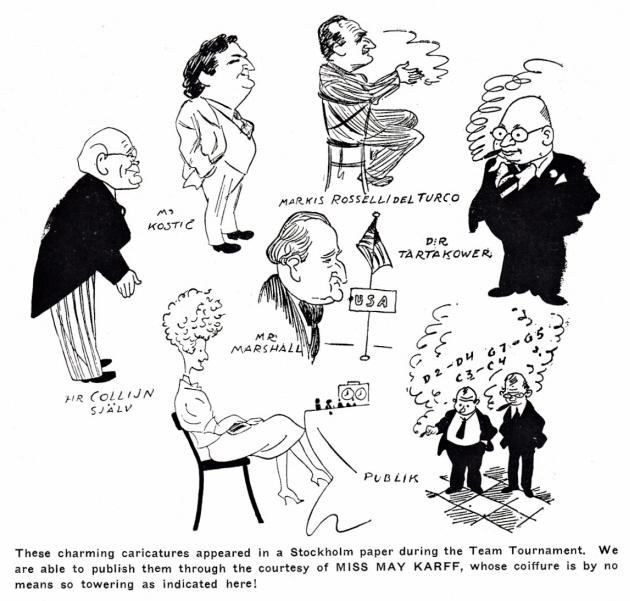

8771. Cartoons

Two photographs in our collection on which we lack any particulars:

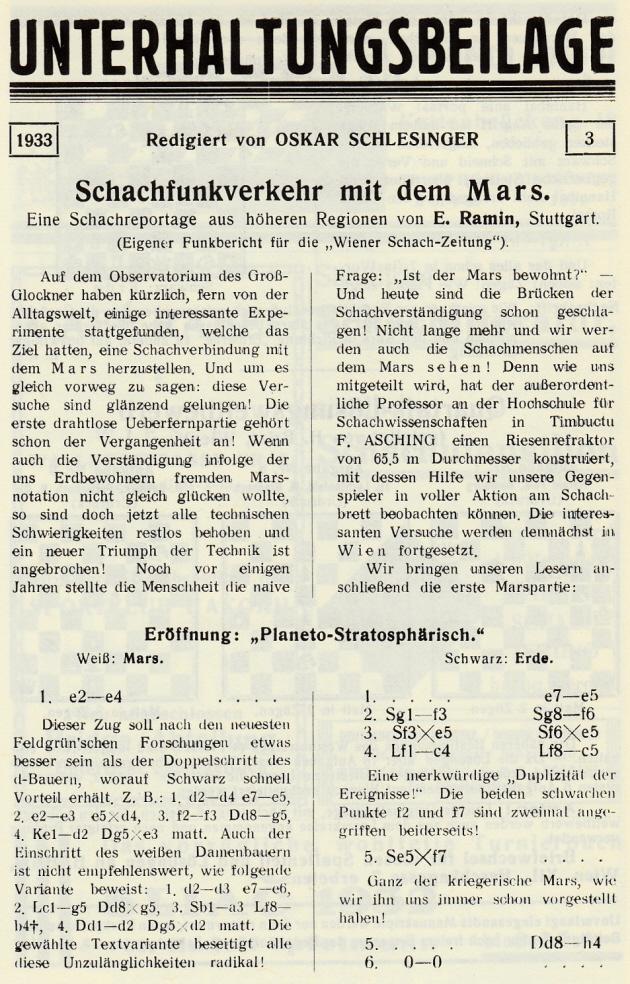

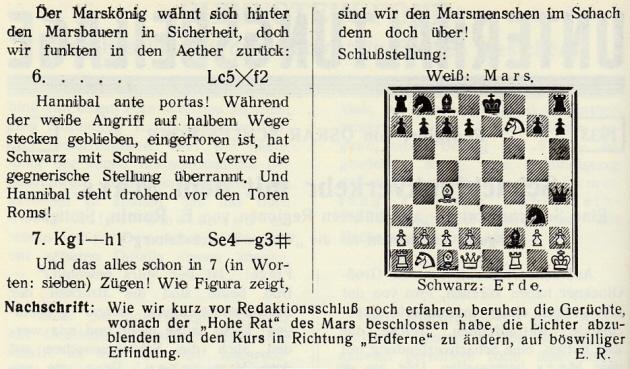

8772. Mars v Earth

C.N. 3975 gave, from the cover pages of the 3/1933 Wiener Schachzeitung, a game between Mars and Earth. Below is the full article:

The game was also published on pages 49-50 of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français, March-April 1933.

8773. The internees (C.N. 3540)

From Tony Gillam (Nottingham, England):

‘Almost all of the questions raised by your correspondent are answered in my new book, Mannheim 1914 and the Interned Russians, but I can answer some of them very briefly.

Janowski was not interned; neither was Fahrni (a Swiss national).

The list of 11 Russians named as interned is correct. None of them “escaped”. Four were allowed to leave, but Alekhine did lie about how he left Germany. As far as I know, no non-Russians were interned. As your correspondent said, there were very few players at Mannheim who were not German, Austro-Hungarian or Russian. The only British national, Gundersen, an Australian, managed to get out of Germany in a very interesting story that is told in full in the book. There were a few “Russians” (mainly from the Baltic states) who were living in Germany and who returned to their (German) homes around the time that war was declared. Some of them were probably interned, but not with the main group of chessplayers.’

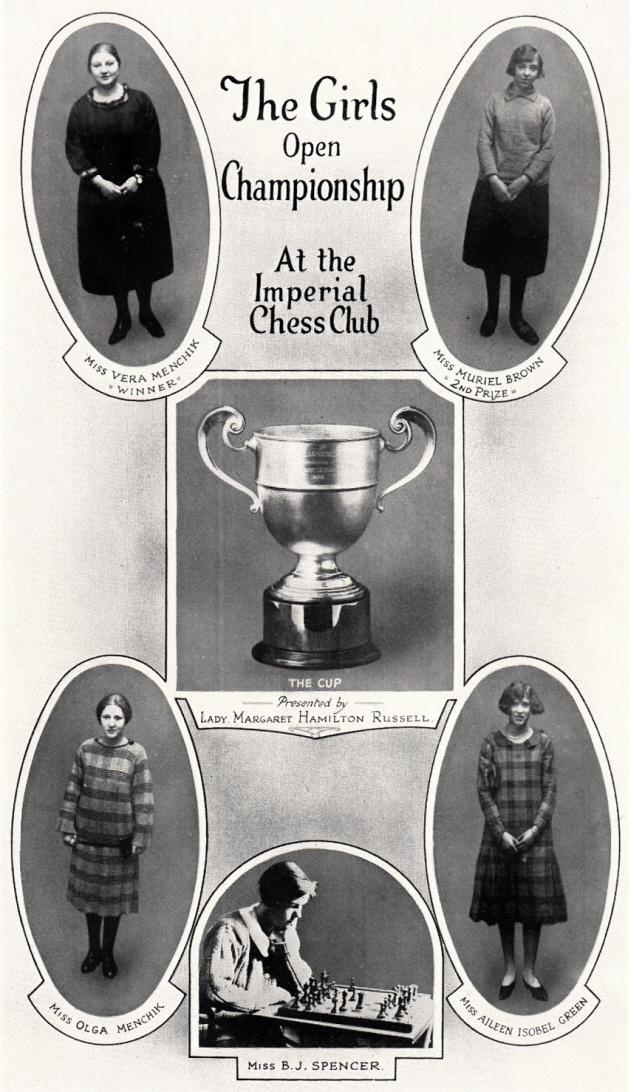

8774. The Menchik sisters

The frontispiece of the February 1926 BCM:

8775. Recommended booksellers (C.N.s 4737, 6147, 6659 & 7342)

Another recommendation: Chess Direct Ltd. (Mexborough, England).

8776. ‘Bubonic plagiarist’

The two most recent issues of Private Eye ask how The Times can possibly continue to employ Raymond Keene, who is described as a ‘bubonic plagiarist’.

Plagiarism is one of the most shameful offences that a writer can commit, and the case against Mr Keene is incontestable. On the other hand, given all his further shortcomings (a whopping euphemism), why would any publication want him even if he had never stolen a single sentence?

8777. The Fried Liver Attack

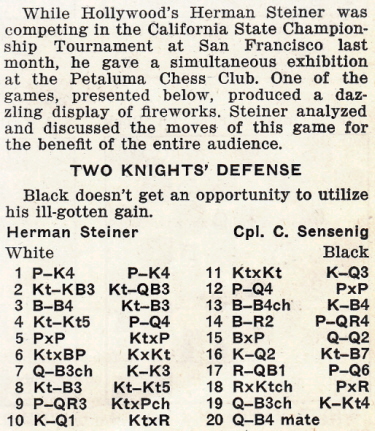

Alexei Shirov’s win over Šarūnas Šulskis at the Tromsø Olympiad on 3 August 2014 (1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 Ng5 d5 5 exd5 Nxd5 6 Nxf7 Kxf7 7 Qf3+ Ke6 8 Nc3 Nb4 9 a3 Nxc2+ 10 Kd1 Nxa1 11 Nxd5 Kd6 12 d4 Be6 13 Re1 b5 14 Nb4 bxc4 15 Qc6+ Ke7 16 Bg5+ Kf7 17 Bxd8 Rxd8 18 Qxc7+ Rd7 19 Qxe5 Rd6 20 d5 Bd7 21 Qf4+ Kg8 22 Qxc4 a5 23 Nd3 a4 24 Nc5 h5 25 Nxd7 Rxd7 26 d6+ Kh7 27 Re6 g6 28 Rxg6 Resigns) repeated up to move 12 a victory by Herman Steiner in a simultaneous display in the mid-1940s. According to the databases that we have consulted, his opponent was ‘N.N.’ or ‘David Rosenberg’, but the name on page 21 of the February 1945 Chess Review was Cpl. C. Sensenig:

See too pages 386-387 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1955).

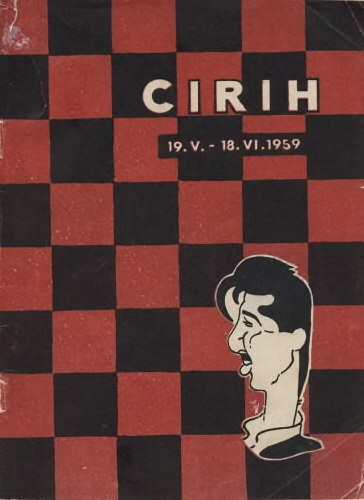

8778. Fischer caricature (C.N. 8724)

From Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England):

‘The Fischer caricature is included in the montage on the front cover of the Winter 1961 issue of the American Chess Quarterly:

The montage appears to come from promotional material for the tournament held in Bled on 2 September-4 October 1961. It features the 20 contenders, plus Milan Vidmar, the tournament director.

The website referred to in C.N. 8724 mentions that the caricatures shown were from a tournament in Yugoslavia in 1959. However, only the first group image of eight is from the Candidates’ tournament held there in 1959.

Three of the larger images are included in the montage from Bled, 1961 (Fischer, Matanović and Petrosian), but I cannot identify most of the other large images. However, a similar caricature to one of these (although Gligorić is facing in the opposite direction) is on the cover of a booklet, published in Belgrade, on Zurich, 1959:’

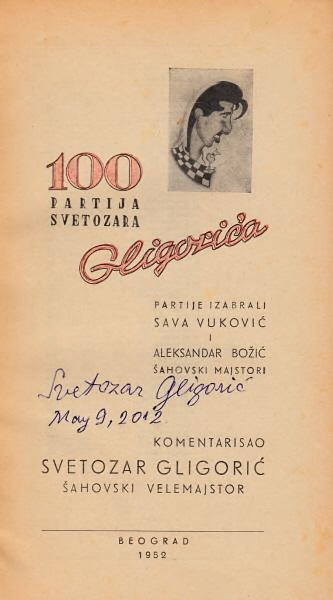

The other caricature of Gligorić referred to by Mr Clapham was also on the front cover and title page of 100 partija Svetozara Gligorića (Belgrade, 1952). From our copy:

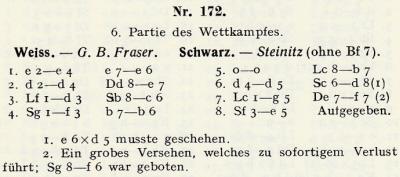

8779. Fraser v Steinitz

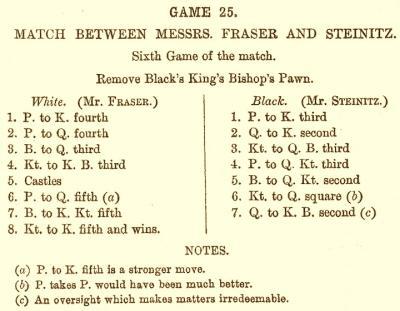

Hayoung Wong (Bayside, NY, USA) writes regarding a game at the odds of pawn and move which Steinitz lost to Fraser in 1867. The score was given in C.N. 1216 (see page 56 of Chess Explorations), taken from page 182 of volume one of Schachmeister Steinitz by Ludwig Bachmann (second edition, Ansbach, 1925):

But did Steinitz resign at move eight? Mr Wong notes that when the score was published on page 107 of the Chess Player’s Magazine, April 1867 the conclusion was 8 Ne5 ‘and wins’:

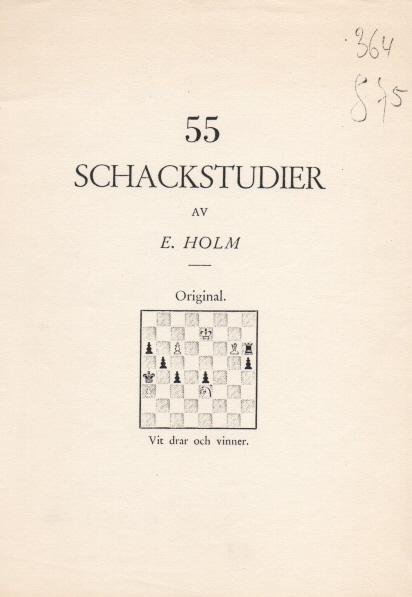

8780. A study by Ernst Holm (C.N. 8755)

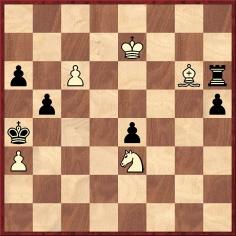

The diagram given in C.N. 8755:

The key move supplied by the composer, Ernst Holm of Ystad, was 1 c7, and the study was due to receive the first prize. However, 1 Bxe4 was subsequently suggested as an alternative solution.

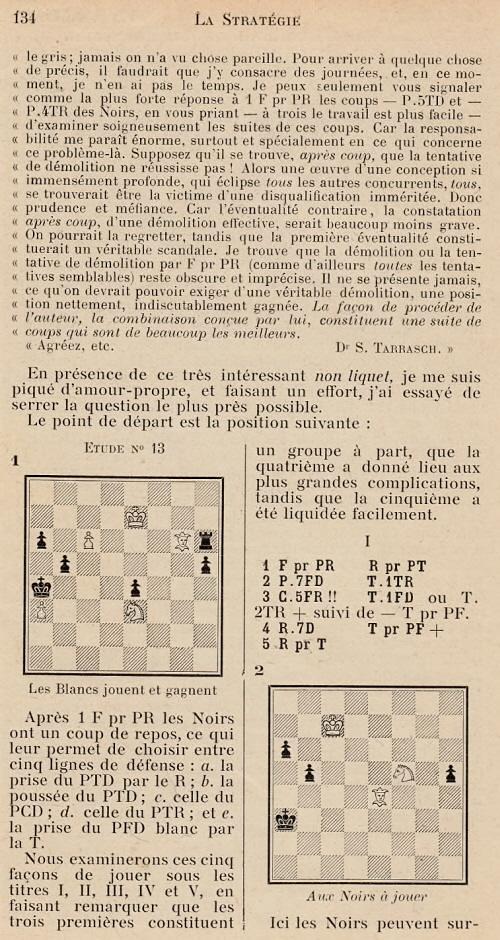

James Ward (Spiddal, Ireland) has raised this subject, having recently acquired the 80-page book Concours international d’Études-Fins de Partie de La Stratégie (Paris, 1914):

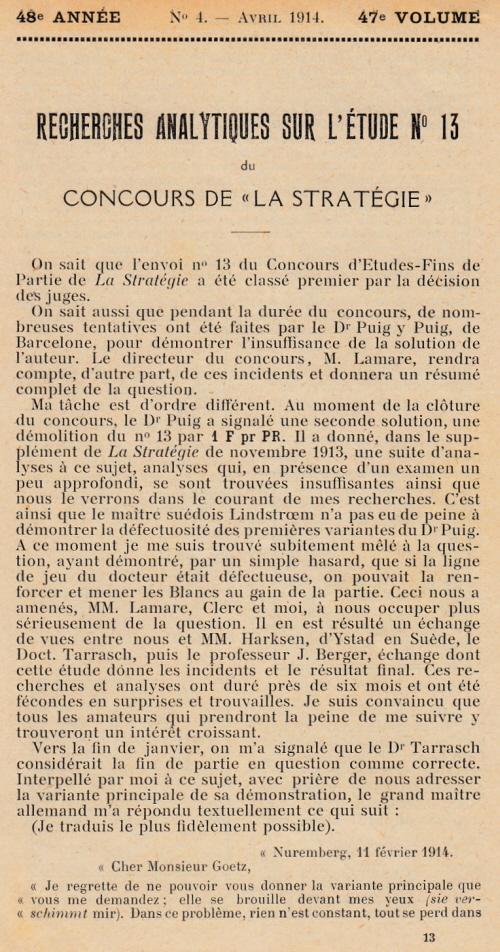

There was much controversy over the soundness of the winning study, which was eventually subjected to detailed analysis by Alphonse Goetz (‘Recherches analytiques sur l’étude No 13’ ) on the last 18 pages of the book. That material also appeared in La Stratégie, April 1914, pages 133-141 and May 1914, pages 180-188, and the first two pages reported an attempt to draw Tarrasch into the affair:

At the conclusion of his analysis Goetz reported that Holm had elegantly withdrawn his study. The final table of prize-winners, who included H. Rinck and F. Lazard, states that the first prize (200 francs) was not awarded.

An enormous amount of analysis of the study can also be found in Harold van der Heijden’s endgame database. An article by Alain Pallier on the concours was published on pages 214-218 of issue 193 of EG (July 2013).

8781. The first world championship

‘The first recognized world championship was played between two Germans – Tarrasch and Lasker – and took place at Munich in 1908, resulting in a victory for Lasker.’

Source: Learn to Play Chess by King’s Pawn, page 6.

The book, undated, was published by The Liverpolitan Ltd. in Birkenhead, England. Its entry on page 132 of D.A. Betts’s Annotated Bibliography gave 1961 as the year of publication and indicated that the identity of King’s Pawn was unknown.

8782. Irving Chernev

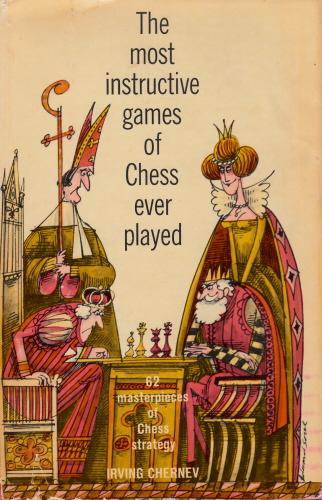

C.N. 8196 discussed The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played by Irving Chernev, a book which had a profound influence on John Nunn, and we commented: ‘An algebraic version has yet to be produced and would be very welcome.’

An algebraic edition has now been published, by Batsford (‘an imprint of Pavilion Books Company Limited’).

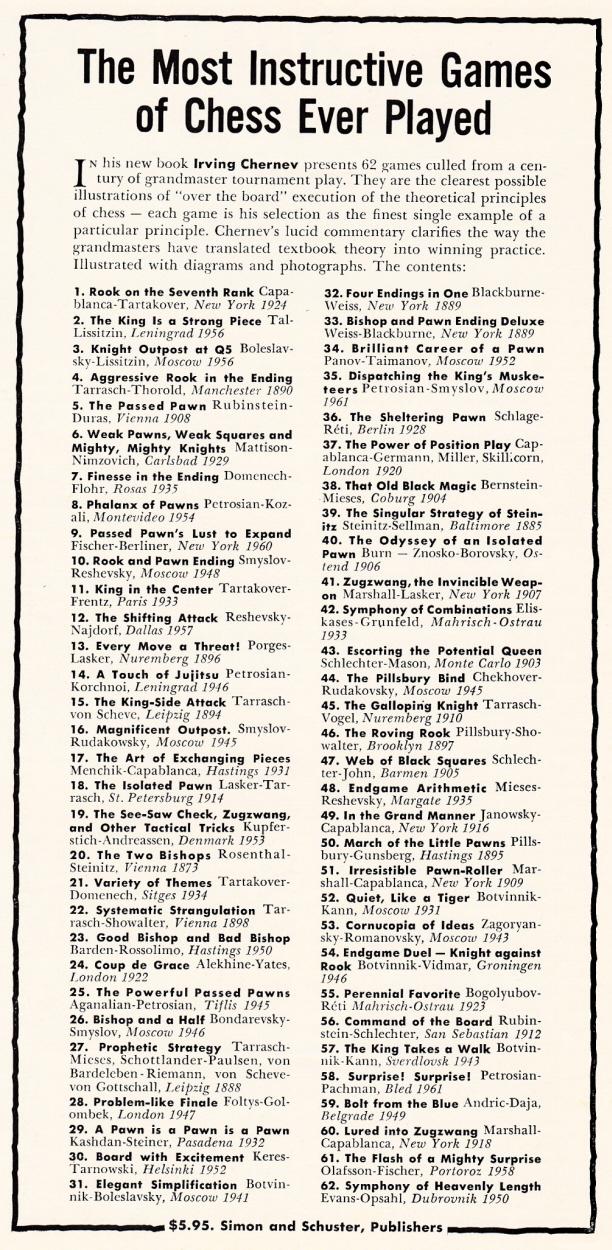

When it first appeared, in the mid-1960s, the book received extensive coverage in Chess Review, although not in Chess Life, and on page 39 of the February 1966 Chess Review an advertisement listed all 62 games selected by Chernev:

The February 1966 issue of Chess Review also had, on pages 46 and 64, a lengthy, highly favourable review by John W. Collins. As regards the production standards he observed:

‘Designed by Cecile Gutler [sic – Cutler], the physical aspects of the book are attractive. The cover design and frontispiece by Edward Sorel is one of the most original to appear. The binding is red and sturdy, the paper and type good ... and the photographs striking (these last are a welcome additive too many publishers omit for economy).’

All the photographs have been omitted from the Batsford edition. In common with other recent Batsford books (most notably, the 2008 edition of Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games), the volume as a whole (a paperback, naturally) looks drab, despite some attempt to replicate the textual lay-out of the original.

‘Drab’ would never describe Chernev’s writing, and in The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played he was perhaps at his best. Collins wrote:

‘... one feels this latest book is the true Chernev, one might say the ultimate Chernev. It gives full vent to his enthusiasm, wit, admiration of the positional-strategic and his encyclopedic knowledge of the Royal Game. Much of this is evident in his previous works, but this time it all comes out.’

This reference to Chernev’s qualities, and not least his

knowledge, is certainly justified. Although C.N. items

have shown that he sometimes cut corners, he was active at

a time when writing and scholarship were not regarded as a

natural pairing and when anecdotes and other chestnuts

were particularly prevalent. Few were interested in

sources. Above all, in the pre-digital age the work of

writers in his field was far harder; they could not fill

in gaps in their knowledge with press-of-a-button

‘research’.

Chernev’s output – clear, humorous and easy-going – gave the impression of effortlessness, but much industry lay behind it all. On 19 January 1977 he wrote to us:

‘I think you will be pleased to hear that I have sent off to Oxford University Press my completed manuscript of Capablanca’s Best Chess Endings, a labour of love (and hard work).’

Although his prose was often conversational, it was literate and carefully structured, bearing no resemblance to the ultra-casual ‘I’m-just-one-of-the-lads’ stuff increasingly seen in chess books and magazines since his time. We have also been struck by the scarcity of typographical errors in Chernev’s writing throughout his life.

Relatively few of his own games are readily available, although it is not difficult to find unknown or little-known scores. Two games from Section B of the preliminaries for the 1942 US championship, including the one below against Altman, were published on page 29 of the March-April 1942 American Chess Bulletin.

Irving Chernev – Benjamin Altman

New York, 1942

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 Be7 5 Bg5 h6 6 Bh4 Nbd7 7 e3 c6 8 Bd3 dxc4 9 Bxc4 Nb6 10 Bb3 Nbd5 11 O-O O-O 12 Rc1 Nxc3 13 bxc3 b6 14 Ne5 Bb7 15 Qd3 c5 16 f3 Bd6 17 Bc2 g6 18 Nxg6 c4 19 Qxc4 fxg6 20 Qxe6+ Kg7 21 e4 Qe7 22 Qh3 Bc8 23 g4 g5 24 Bf2 Bf4 25 Rcd1 Qa3 26 e5 Nd5 27 Be4 Ba6 28 Bxd5 Rad8 29 Bb3 h5 30 Rfe1 Rh8 31 Be3 Rdf8 32 Bxf4 Rxf4 33 gxh5 Bc8 34 e6 Qd6 35 Re5 Kf6 36 h6 Rh7 37 Qh5 Ke7 38 Qxg5+ Rf6 39 Rde1 b5 40 R1e4 Rhxh6 41 Qg7+ Ke8 42 Rg4 Bxe6 43 Bxe6 Rxe6

44 Qxh6 Qxe5 45 Qxe6+ Qxe6 46 Re4 Resigns.

In the other game on that page, Chernev’s opponent, D. Podhorcer, blundered early on: 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 c4 b6 4 g3 Bb7 5 Bg2 Be7 6 Nc3 Ne4 7 Qc2 Nxc3 8 bxc3 f5 9 O-O Be4 10 Qa4 O-O 11 Ne1 Bxg2 12 Nxg2 d6 13 Nf4 Qc8 14 d5 e5 15 Ne6 Rf6 16 Be3 Nd7 17 Qc6 Nf8 18 Nxc7 f4 19 Kg2 Rh6 20 h4 Rb8 21 Na6 Qxa6 22 White resigns.

A third game from the same event was published on page 63

of the July-August 1942 American Chess Bulletin:

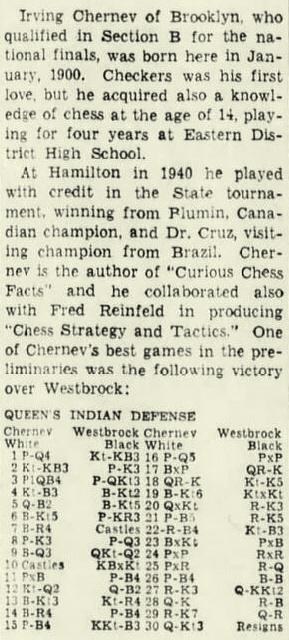

Irving Chernev – John T. Westbrock

New York, 1942

Queen’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 c4 b6 4 Nc3 Bb7 5 Qc2 Bb4 6 Bg5 h6 7 Bh4 O-O 8 e3 d6 9 Bd3 Nbd7 10 O-O Bxc3 11 bxc3 c5 12 Nd2 Qc7 13 Bg3 Nh5 14 Bh4 f5 15 f4 Nhf6

16 d5 exd5 17 Bxf5 Rae8 18 Rae1 Ne4 19 Bg6 Nxd2 20 Qxd2 Re6 21 f5 Re4 22 Rf4 Nf6 23 Bxf6 gxf6 24 cxd5 Rxf4 25 exf4 Rd8 26 c4 Bc8 27 Re3 Qg7 28 Qe1 Rf8 29 Re7 Qh8 30 Qg3 Resigns.

The Westbrock game was also on page 16 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 2 April 1942:

The Eagle was apparently mistaken about Chernev’s place of birth (‘here’). His date of birth was discussed in C.N. 3007 (see page 98 of Chess Facts and Fables).

The most detailed article about him is ‘An Invitation to Chernev’ by Jerome Tarshis on pages 500-503 of Chess Life & Review, September 1979. Some recollections quoted on page 501:

‘The writing that I did was done on weekends and after hours ... It was only when I had an idea that I thought merited a book that I would do a book, and then I would spend a lot of time on it. For example, when I wrote The 1000 Best Short Games of Chess, I went through some 15 to 20 thousand games, to pick out games that were dissimilar and weren’t just baby traps, or dreadful blunders in the opening.

When I wrote Logical Chess Move by Move – and this also applies to The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played – I went through hundreds and hundreds of games that were mostly positional in character. I wanted to be able to point out that the positional play was more important, and that the combinations would come of themselves.

It wasn’t easy to choose the games. In a lot of fine games there are a great many moves that are not exactly meaningless but are difficult to explain to the average or below-average player. And it wasn’t enough for me to find a good game where the two bishops are better than the two knights. I wanted to find the very best example.’

8783. Politics

‘Politics is just a game in England today. Our leading men play it just as we play chess. There is very little consideration of Statesmanship or what is best for the Country and the Empire at large. The main question is the game – which move will best suit the scramble for place and power.’

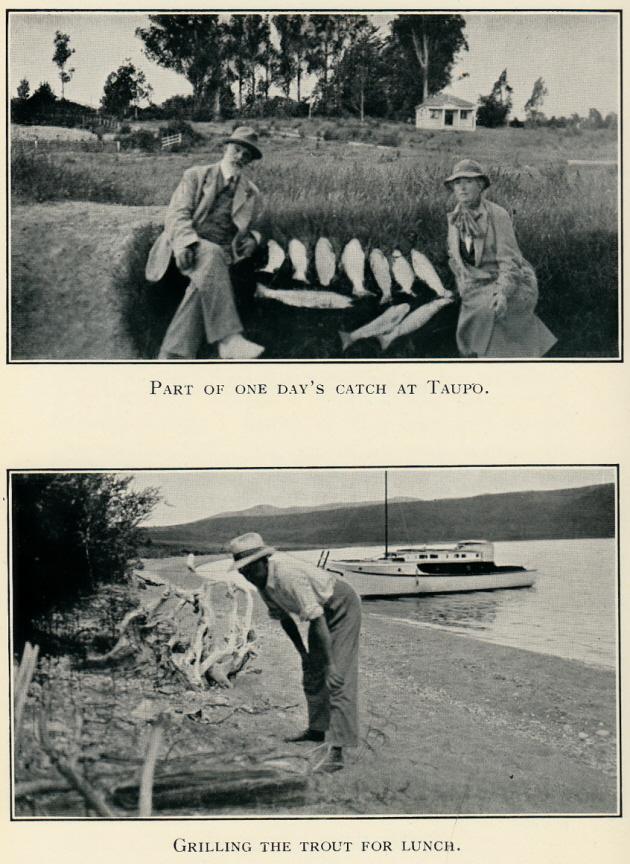

Source: unnumbered page in the chapter ‘The Pacific Ocean’ in Across the World by Samuel Tinsley (London, 1937), the book discussed in C.N. 8725.

The photographs below of Tinsley and his wife are in the chapter on ‘The Dominion of New Zealand’:

8784. Fraser v Steinitz (C.N. 8779)

From Tim Harding (Dublin):

‘The game was played on 29 January 1867 and was published on 31 January in the Dundee Advertiser, page 3. This was the earliest publication of the game.

After White’s eighth move the newspaper said, “and Mr Steinitz resigns, the queen being lost”.

In general, I have often found with Victorian games that a source may say “and wins” without it necessarily meaning that there were further moves. Sometimes, as here, another source explicitly says “resigns”.’

Our correspondent, it will be recalled, is the author of Eminent Victorian Chess Players (Jefferson, 2012).

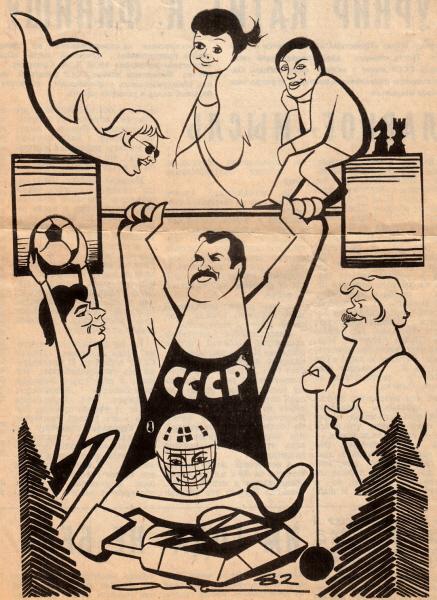

8785. 1982 cartoon featuring Karpov

Further to C.N. 8771, below is a cartoon (cutting only) from an unidentified Soviet newspaper:

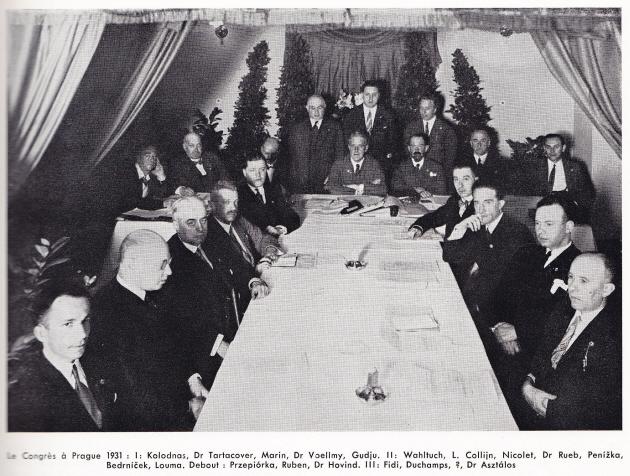

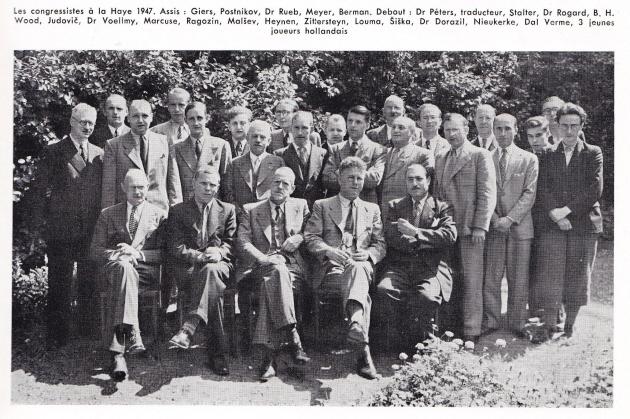

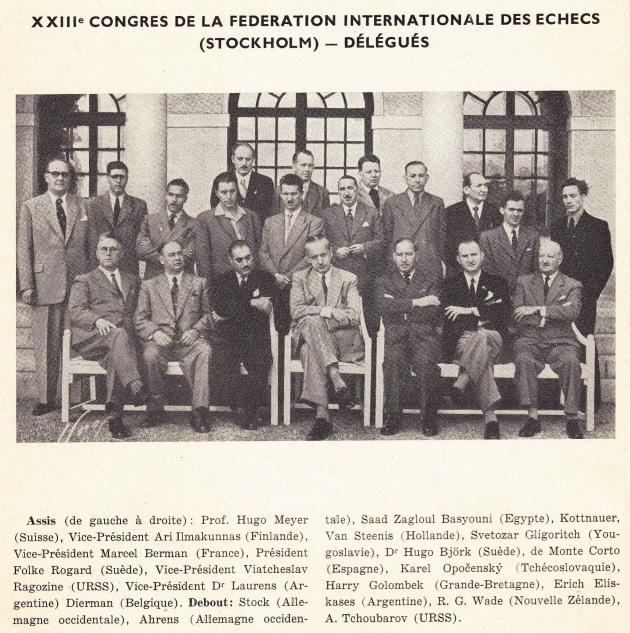

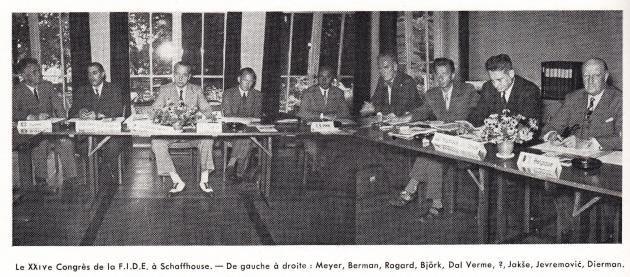

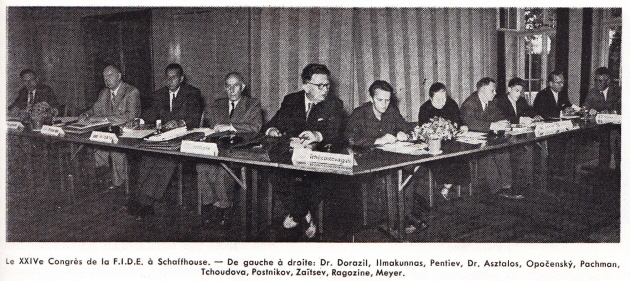

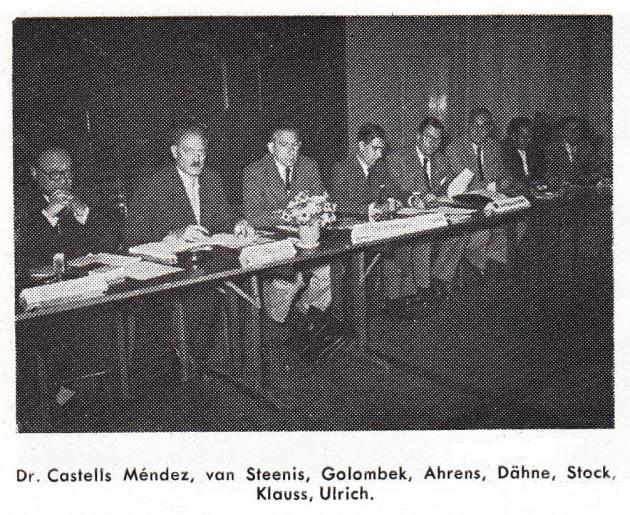

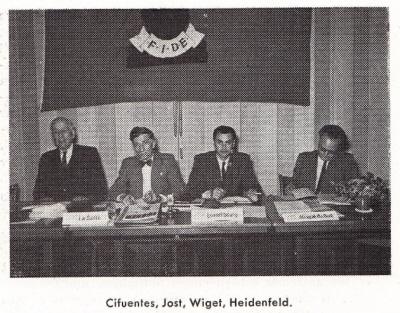

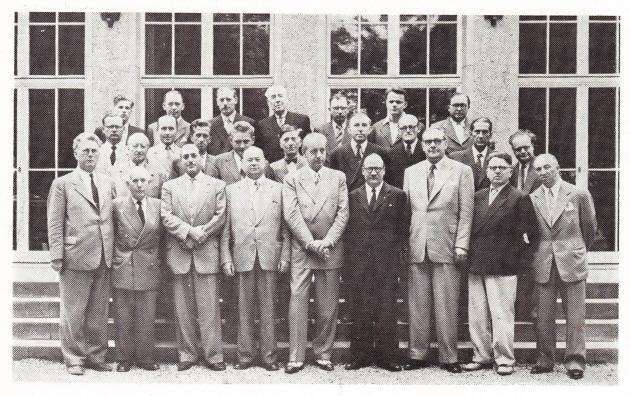

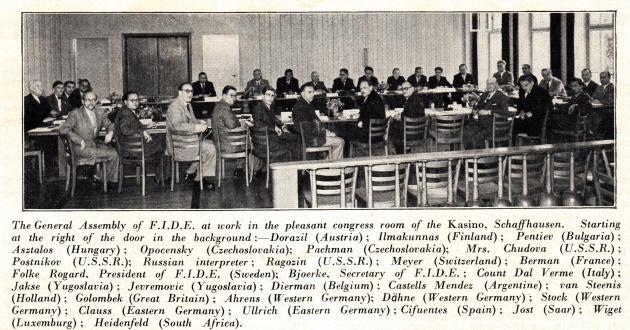

8786. FIDE group photographs

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) has forwarded a number of photographs which will be added in due course to Chess: The History of FIDE:

Source: FIDE Revue, 1/1955, page 3.

Source: FIDE Revue, 1/1955, page 5.

Source: FIDE Revue, 1953, page 4 (1952 Congress).

Source: FIDE Revue, 1/1954, page 2.

Source: FIDE Revue, 1/1954, page 5.

Source: FIDE Revue, 1/1954, page 6 (1953 Congress

in Schaffhausen).

Source: FIDE Revue, 1/1954, page 7 (1953 Congress in Schaffhausen).

Source: FIDE Revue, 1/1954, page 10 (1953 Congress in Schaffhausen – no caption given).

The photograph below is from page 5 of CHESS, October 1953:

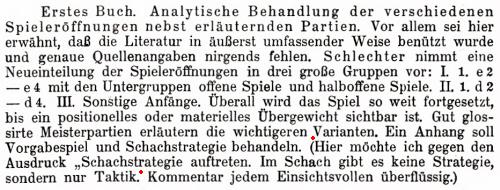

8787. Tactics

On page 195 of The Art of Positional Play (New York, 1976) Reshevsky agreed with the remark regularly ascribed to Teichmann (see C.N. 8738), ‘Chess is 99% tactics’.

An addition on the same theme comes from an article entitled ‘Der neue Bilguer’ by Josef Krejcik on pages 230-232 of the August-September 1913 Wiener Schachzeitung:

The marked passage states:

‘Here I wish to speak out against the term “chess strategy”. In chess there is no strategy, but only tactics.’

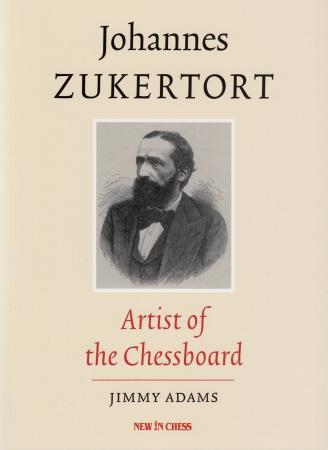

8788. Zukertort

Below is a brief book notice which we wrote in 1989 (in C.N. 1928):

Anyone can fill a page on Zukertort; ‘physician ... linguist ... war hero ... shattered by his foe Steinitz, etc.’, all topped off with the inevitable Zukertort v Blackburne, London, 1883 (28 Qb4!!). What has always been needed is a detailed study of his career, a gap now filled by Johannes Zukertort Artist of the Chessboard by Jimmy Adams (Caissa Editions, Yorklyn, $48). In the 1980s Adams had already made an outstanding contribution to chess literature, and the Zukertort work (all 534 pages of it) is another fine achievement. A hundred and thirty pages of historical material are followed by 319 annotated games, most long forgotten. Proof-reading has been excellent, and our only criticism concerns the absence of exact source references for material quoted (historical features as well as game annotations). Ironically, the hero of this book (apart from the subject and author) is Steinitz, whose wonderful annotations to Zukertort’s games are quoted on many occasions and put others to shame.

The book has just been re-issued as a paperback by New in Chess, with virtually no textual changes. Given the general improvement in chess scholarship since 1989, the absence of information about sources looks even worse today. The publisher has, though, added some photographs.

8789. ‘Was I frightened?’

A rare game featuring the problemist P.H. Williams:

Philip Hamilton Williams – Hammant

Occasion?

Centre Game

1 e4 e5 2 d4 Nc6 3 d5 Nce7 4 c4 d6 5 Be3 h6 6 Nf3 Nf6 7 c5 Ng6 8 Qa4+ Bd7 9 c6 bxc6 10 dxc6 Be6 11 Ba6 Ng4 12 Bb7 Nxe3 13 Bxa8 Nxg2+ 14 Kf1 Bh3 15 Bb7 N6f4 16 Nbd2

16...Ne3+ 17 Ke1 Neg2+ 18 Kd1 Nd3 19 Qxa7 Be7 20 Kc2 Ngf4 21 Rhg1 O-O 22 Rg3 Be6 23 Ne1 Nxe1+ 24 Rxe1 Bh4 25 Ra3 Nh3 26 Rf1 d5 27 Rd3 d4 28 f3 Bc4 29 Nxc4 Nf4 30 Nxe5 Nxd3 31 Kxd3 Qe7

32 Qxd4 Rd8 33 Nd7 Bf6 34 Qf2 Qb4 35 Rb1 Qb5+ 36 Kc2 Qc4+ 37 Kd1 Qd3+ 38 Kc1 Qc4+ 39 Qc2 Bg5+ ‘and wins’.

The game, which contains a number of oversights, was annotated by W.P. Turnbull on pages 74-75 of the Chess Amateur, December 1908. In his problem column in the same issue Williams wrote, on page 89:

‘The “P.E.” [Problem Editor] as a Match Player

Yes, I really did play in a match a short time ago, and I have made so bold as to submit the game to the Games Editor. It is to be found on page 74 of this issue. It will be seen from it that my opponent didn’t care a penny stamp for P.H.W., nor did P.H.W. care one for him – no, not even one with the gum licked off. The result was that we went for each other like a brace of rival Socialist orators in the Park. I was smashed. But the funny thing about it was that I was quite happy until the very last moment, and was just thinking of borrowing the cigarette (with match complete) which I deserved, when I covered a certain check with a pawn, and my jaw fell as it was removed (the pawn, that is) followed by a saucy mate. My man said he was ready for a perpetual even at the penultimate move. All the same, I had great fun; when those two black knights came pottering around, was I frightened? Not a bit of it. I merely dodged round and sailed out on the other side, with the exchange to the good. Oh, it was all so nice. But I was smashed. Do you know why I overlooked the mate? No? Neither do I, but I broached the kegs of rum before the ship went down. The opening was the Jackass gambit with Terra del Fuego variations in F-sharp minor. (See my treatise on the openings, page 2668.)’

8790. The Mark Twain of the chess world

From John Keeble’s review of Chess Chatter & Chaff by P.H. Williams (Stroud, 1909) on page 48 of the November 1909 Chess Amateur:

‘Mr P.H. Williams has a style that is quite his own. He has been called the “Mark Twain” of the chess world – a compliment well deserved. He has a keen sense of humour, which, by the way, is generally directed against himself, for he introduces himself into most of his writings. If, for instance, we find that anyone in a tale gets a black eye, it is sure to be the author, and so on. Another marked feature of Mr Williams’ literary work is that he is equally at home either with prose or poetry, a thing that can scarcely be said of any other chess writer of the present day.’

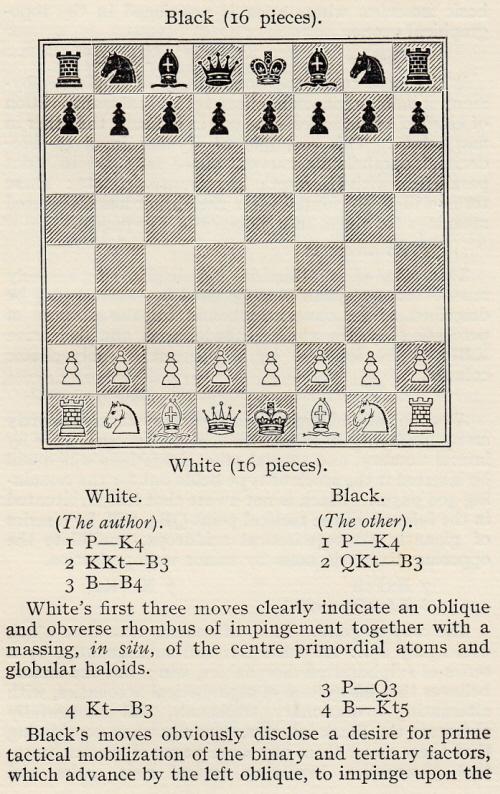

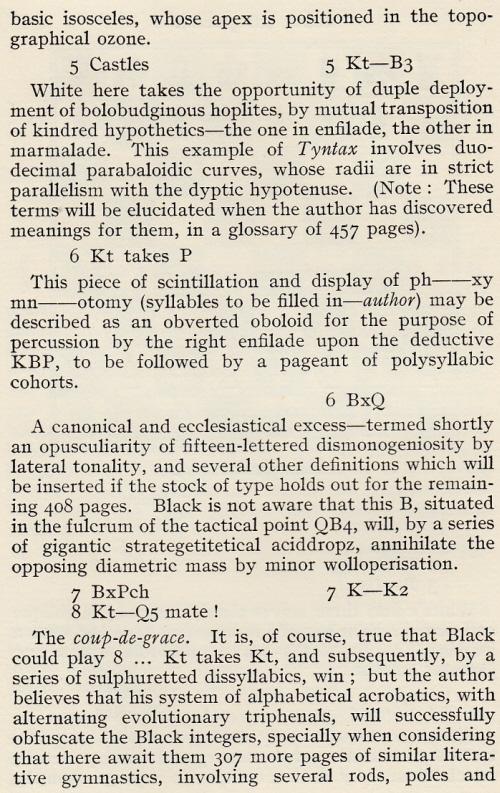

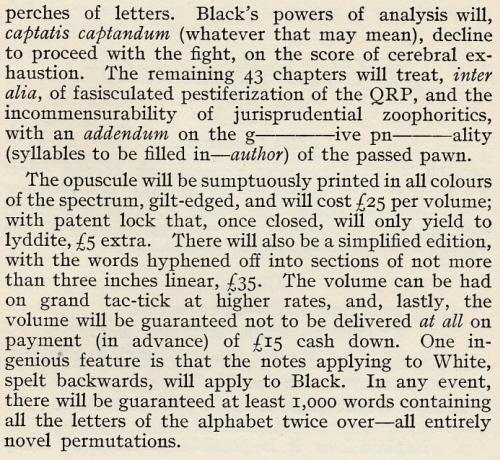

Mention was also made of Williams’ skill as a parodist, and below we give, from pages 74-77 of Chess Chatter & Chaff, his mockery of the books of Franklin Knowles Young:

8791. Adjectives for Kasparov

From page 225 of The Rocket That Fell to Earth: Roger Clemens and the Rage for Baseball Immortality by Jeff Pearlman (New York, 2009):

‘For so much of the season, Clemens came off as baseball’s Garry Kasparov – cold, indifferent, unemotional.’

The quote has been forwarded by Tony Bronzin (Newark, DE, USA), who comments:

‘I can conjure a few adjectives to describe Kasparov, but “cold, indifferent, unemotional”?’

8792. A study by Ernst Holm (C.N.s 8755 & 8780)

Additional information and references have been received from Alain Pallier (La Roque-d’Anthéron, France), who wrote about the Holm study in Europe Echecs, March 1998, pages 62-63, and April 1998, pages 60-61. The EG article by Mr Pallier mentioned in C.N. 8780 was one of a series which he contributed to the studies magazine:

- ‘Study tourneys from the past – La Stratégie (part 1)’: EG 191, January 2013, pages 13-17;

- ‘Study tourneys from the past – La Stratégie (part 2)’: EG 192, April 2013; pages 115-120;

- ‘Study tourneys from the past – La Stratégie 1912-1914 (part 3)’: EG 193, July 2013; pages 214-218;

- ‘Study tourneys from the past – La Stratégie 1912-1914 (part 4)’: EG 194, October 2013; pages 317-321.

The articles confirm that following the decision that Ernst Holm’s composition would not, after all, receive first prize, the runner-up, Rinck, incorrectly claimed to have won the competition. Moreover, when Holm published a collection of his compositions, 55 Schackstudier (Stockholm, 1937), he made no reference to the La Stratégie study but, as shown in the scan below provided Mr Pallier, gave on the front cover a corrected version (with a black pawn added on c4):

Our correspondent recently learned that the Holm study was discussed by A. Werle on pages 57-58 of Tidskrift för Schack, February 1952.

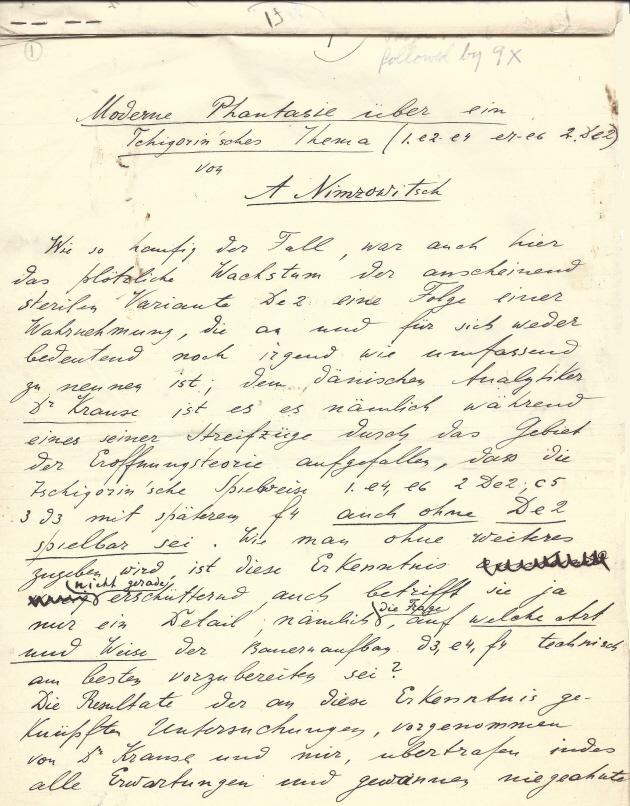

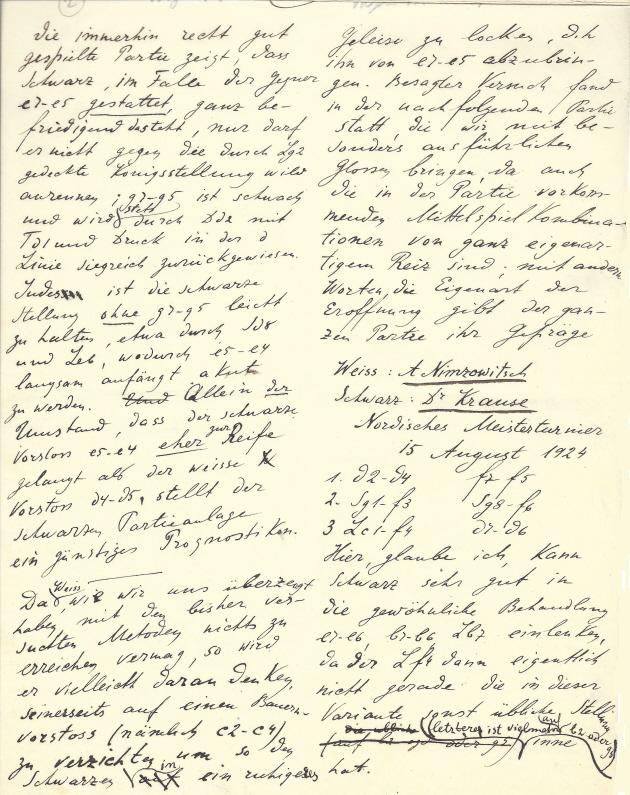

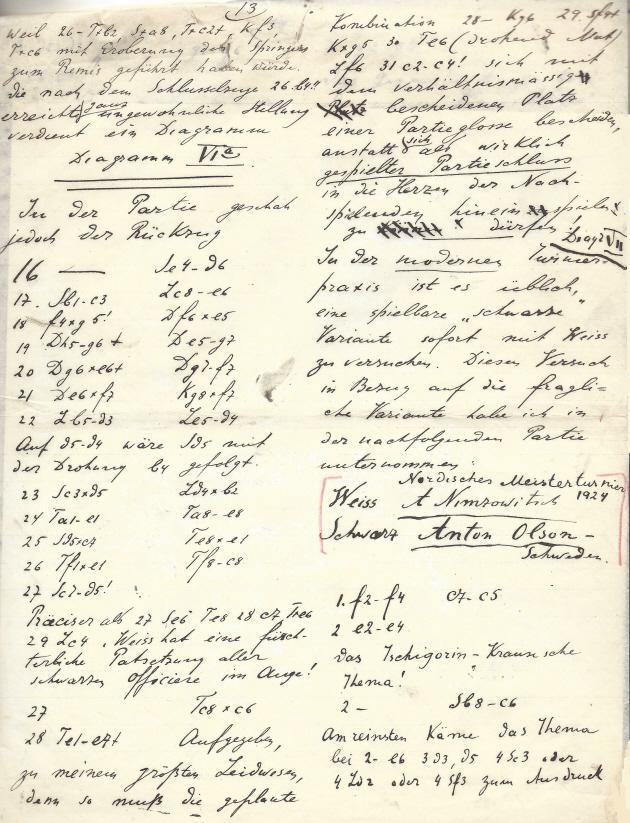

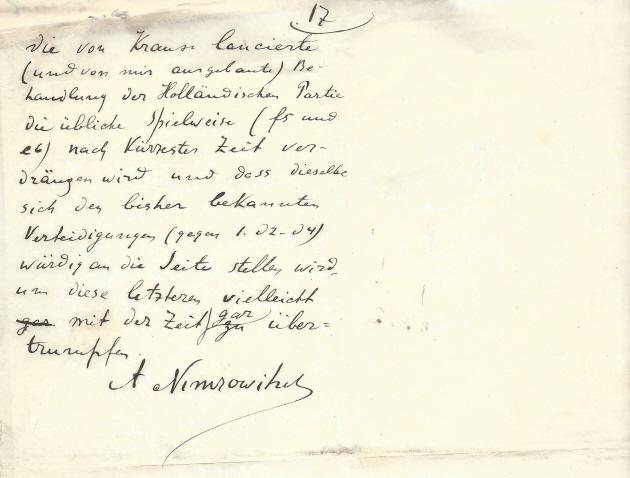

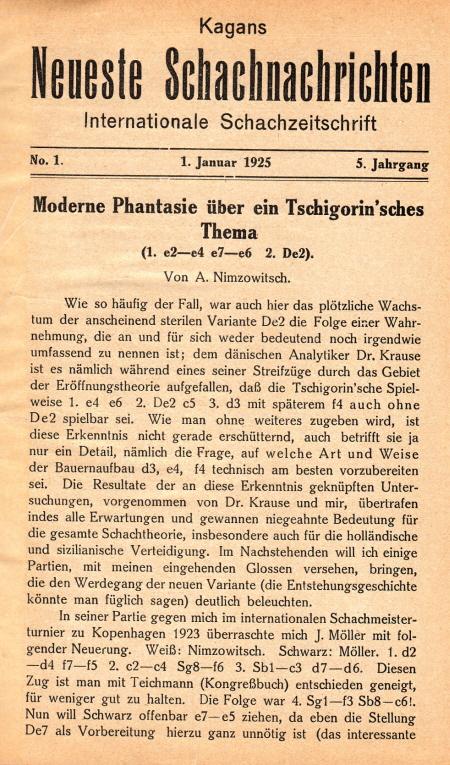

8793. Nimzowitsch manuscript

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) owns a 17-page

article handwritten by Nimzowitsch and has kindly provided

four sample pages:

We can add that the article, ‘Moderne Phantasie über ein Tschigorin’sches Thema (1 e2-e4 e7-e6 2 De2)’, was published on pages 1-12 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, 1 January 1925:

8794. Diggle on E.S. Tinsley

An extract from the article by G.H. Diggle referred to in C.N. 8725 (first published in the June 1979 issue of Newsflash):

‘He was a well-known character at chess congresses between the Wars – a dignified, florid, slightly ponderous man, with notebook in hand and pencil poised at the ready, wandering from board to board like “the friendly cow, all red and white” and compiling such mildly censorious thunder as “X went sadly astray on the tenth move” or “Y appeared completely unfamiliar with this line of play”. He had his detractors, as his own chess achievements were something of a mystery; and congress cynics whose play he had criticized reacted sometimes with jocular slanders about “old Tinsley”, comparing him with the celebrated public school games master who stood on the brink of the swimming bath upbraiding his struggling pupils until one day he fell in himself, couldn’t swim a yard, and had to be fished out. But the truth was, as the BCM obituary put it, that “although in no way approaching his father’s strength at the game, he had a good knowledge of chess, and occasionally played for Kent County”. One master who greatly respected him was Capablanca, who always called at the Times office whenever he was in London. Tinsley always demanded of himself nothing less than 100% accuracy when reporting a congress; the BM once heard him “trumpet loud and long” when a colleague had furnished him with an incorrect result, though the game in question was in a third-class section. His death was tragically sudden – he was actually reporting the Centenary Congress of the Worcester C.C. when he collapsed when the last round was in progress; the players were kept in ignorance until the games were over, and the presentation of the prizes cancelled as a mark of respect.’

8795. Marshall v Dyckhoff

A simultaneous game from pages 106-107 of Schachjahrbuch für 1905 I. Teil by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1905):

Frank James Marshall – Eduard Dyckhoff

Augsburg, 7 April 1905

Max Lange Attack

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 Bc4 Nf6 5 e5 d5 6 Bb5 Bb4+ 7 c3 dxc3 8 bxc3 Qe7 9 O-O Ne4 10 cxb4 Be6 11 Nd4 O-O 12 Nxc6 bxc6 13 Bxc6 Rad8 14 a3 f5 15 Be3 f4 16 Bxa7 f3 17 gxf3 Qg5+ 18 Kh1 Bh3 19 Rg1 Qxe5 20 Bd4

20...Rxf3 21 Rxg7+ Qxg7 22 Bxg7 Nxf2+ 23 Kg1 Nxd1 24 Nd2 Rd3 25 Rxd1 Kxg7 26 a4 Bg4 27 Ra1 Rxd2 28 a5 Rf8 29 a6 d4 30 a7 Rd1+ 31 Rxd1 Bxd1 32 a8Q Rxa8 33 Bxa8 Kf6 34 Kf2 Ke5 35 Ke1 Bc2 36 Kd2 Be4 37 Bxe4 Kxe4 38 h4 c6 39 h5 d3 40 Kd1 Kd4 41 Kd2 h6 42 Kd1 Kc3 43 Kc1 Kxb4 44 White resigns.

The display (+26 –3 =0) was reported on page 156 of the May 1905 Deutsche Schachzeitung.

8796. A study by Ernst Holm (C.N.s 8755, 8780 & 8792)

Ola Winfridsson (São Paulo, Brazil) draws attention to pages 205-222 of the October-December 1914 issue of Tidskrift för Schack.

The article, attributed to A. Lindström, is a Swedish translation of the analysis by Goetz referred to in C.N. 8780.

8797. Problems

‘I know well enough that no amount of argument will make the hardened game enthusiast see anything in problems to interest him. Still it is unfair to sneer at problems simply because you fail to see anything in them. Others do. I have a pet dislike myself – I can’t bear celery, and the fact that ten different people tell me that celery is very nice naturally avails me nothing. But I do not call these ten men names for liking celery.’

Source: Chess Chatter & Chaff by P.H. Williams (Stroud, 1909), page 56.

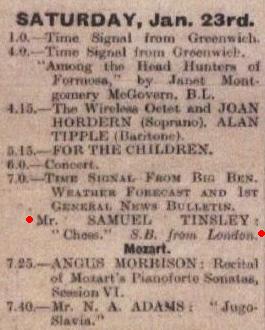

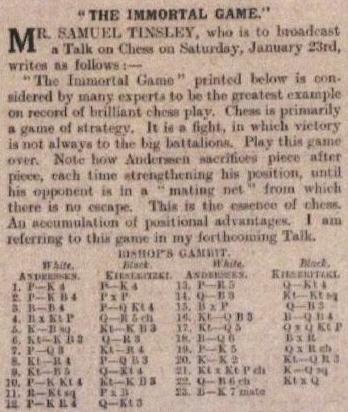

8798. Radio talk in 1926 (C.N. 8725)

Below is the billing for Samuel Tinsley’s talk on chess (British Broadcasting Company, Saturday evening, 23 January 1926) in the programme schedule on page 157 of the Radio Times, 15 January 1926:

‘S.B.’ means simultaneous broadcast.

As shown in C.N. 8725, Tinsley mentioned in his talk that the Anderssen v Kieseritzky ‘Immortal Game’ was published in the same issue of the Radio Times. From page 148:

Permission to show the above material has been received from Immediate Media Company London Limited, the publishers of the Radio Times.

A photograph of Samuel Tinsley from his book Across the World (London, 1937):

Can it be discovered when he died?

8799. Colour photograph of Marshall

Pete Tamburro (Morristown, NJ, USA) asks whether information is available about a photograph which he bought many years ago:

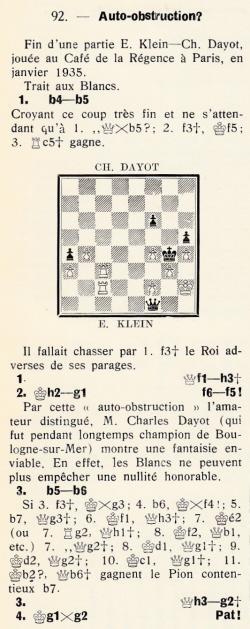

8800. Klein v Dayot

Source: Tartakower’s column on page 998 of L’Echiquier, March-April 1935.

Can further details be found about this specimen of stalemate?

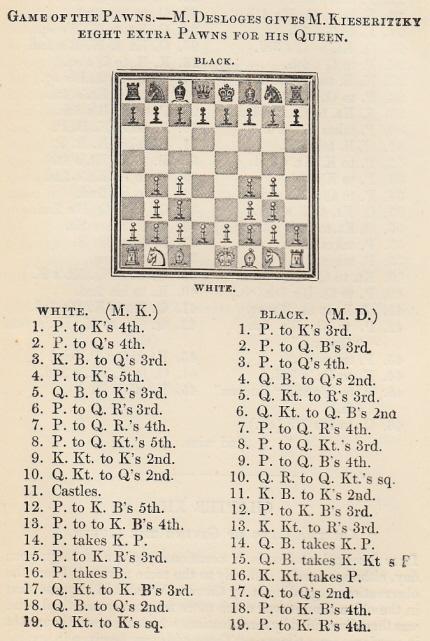

8801. Desloges (C.N. 8659)

C.N. 8659 asked whether the games of the nineteenth-century player Desloges support Alphonse Delannoy’s claim that he ‘affected a very rare predilection, that of creating difficulties, in order to have the pleasure of extricating himself from them’.

Readers may draw their own conclusions from a file of games by Desloges which Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) has compiled (nine games, including two played in consultation). Our correspondent also points out this game on pages 399-400 of the Chess-Player’s Companion by Howard Staunton (London, 1849):

Mr Thimognier, who reports that he has been unable to find Desloges’ forename, adds the following quotes:

‘Le Cercle des échecs de Paris fut institué, il y a quelques années, par M. Alexandre; il se tenait d’abord au café de l’Echiquier; il fut établi ensuite au Cercle des Panoramas. Au nombre de ses membres se trouvaient MM. Deschapelles, de La Bourdonnais, Mouret, Boncourt, Saint-Amant, Calvi, Desloges, Sasias, Dumoncheau, Robello, Chamouillet, Lécrivain, Azévédo et autres forts joueurs.’

Source: Le Palamède, January 1837, page 10.

‘Y a-t-il à Londres un plus grand nombre de forts joueurs qu’à Paris?

Je répondrai à cette question, mais de manière à contenter tout le monde, bien que cependant je ne consigne ici que le consciencieux résultat de mes observations.

Je diviserai donc ma réponse ainsi:

Dans les premières et secondes forces, je n’hésite pas à dire que les amateurs sont plus nombreux à Paris. Autour de M. Staunton se rangent à peine quatre à cinq grandes réputations. Avec MM. Deschapelles et St-Amant, nous possédons à Paris MM. Laroche, Kiezeritski, Calvi, Lécrivain, Sasias, Robello, Devinck, Chamouillet, Desloges, le docteur Laroche, Vuillermet, Hersent, Dumonchau et Lemaître. Je ne compte pas le père Alexandre, qui est des nôtres aujourd’hui, car, le volage, il nous quittera peut-être une fois encore ...’

Source: Le Palamède, 15 December 1845, page 560, in an article entitled ‘Un rédacteur du Palamède à Londres’.

‘Percez ce groupe, examinez cet amateur; son regard foudroye la galerie, sa parole s’exhale en murmurant contre les spectateurs, même au milieu du plus profond silence; son corps se balance à droite, à gauche, en avant, en arrière, sa main ramène l’échiquier en droite ligne, son bras écarte les voisins. C’est cependant le plus doux, le plus aimable des joueurs. Cette brusquerie n’est pas de son caractère, elle provient d’une infirmité. Mais sa partie est compromise et c’est aux observations de la galerie qu’il attribue sa défaite. C’est M. Desloges; athlète intrépide, exceptionnel, hardi jusqu’à la témérité, il affectionnait surtout les parties à avantage: il les jouait en effet avec un bien rare talent et improvisait des prodiges. Labourdonnais l’avait surnommé la Terreur des Mazettes. J’ai pu apprécier longtemps la justesse de ce titre, M. Desloges fut mon maître; pendant six années consécutives, je versai dans son escarcelle des boisseaux de pièces de 50 c., j’ai toujours joué vite, dix parties à l’heure, je les perdais toutes, additionnez.’

Source: La Nouvelle Régence, January 1864, pages 3-4, in an article by Alphonse Delannoy.

Finally, Mr Thimognier notes that Desloges played unusual openings, such as 1...Nc6 and 1...Nf6 in reply to 1 e4. Those knight moves were mentioned in an article by Calvi on irregular openings on pages 385-390 of Le Palamède, 15 September 1845:

‘Ce début et le suivant ..., qui paraîtront inutiles à la plupart des amateurs qui les regarderont comme impraticables, seront appréciés par les habitués du Café de la Régence, où M. Desloges, joueur habile et ingénieux, les emploie souvent contre les adversaires à qui il fait avantage.’

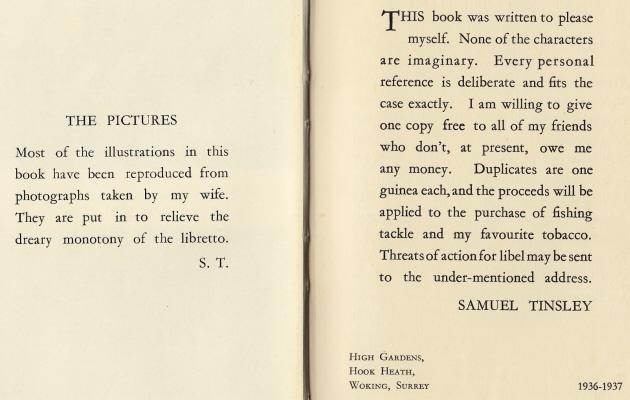

8802. Samuel Tinsley

From Across the World by Samuel Tinsley (London, 1937):

C.N. 8798 asked whether it could be discovered when Samuel Tinsley died, and we have now received the following from John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘That the second son of Samuel Tinsley (1847-1903) was Samuel Tinsley is confirmed in the marriages column of The Gentlewoman, 20 May 1905, page 3:

“Tinsley – Dobson. On 6 May, at the City Temple, London, by the Rev. G.S. Walker, of Stalybridge, Samuel Tinsley, second son of the late Mr Samuel Tinsley of Lewisham, to Marion, only daughter of Mr and Mrs Edward Dobson, of Sidcup.”

Page 10 of the Argus (Melbourne), 3 March 1939 had a brief pen-portrait of him:

“Likes Our Country

Most picturesque figure aboard when the Orcades sailed from Station Pier this week was Mr Samuel Tinsley, of Hook Heath, Woking, Surrey, former London journalist and retired publisher and printer.

Smiling blue eyes twinkled above a Bernard Shaw beard, and a tie and kilt of the McLaren tartan, while a leather sporran matched his Scotch brogues. Add to this a fistful of multi-coloured streamers and you have a picture of a grand old man who thinks that Australia is a wonderful country.

After spending three months in New Zealand and Australia principally fishing, he is going home convinced more than ever that the ‘colonies are solidly behind the mother country’, though he did not specify if that meant England or Scotland.”

Below is an entry for his will in the National Probate Calendar in 1945:

“Tinsley, Samuel of Fieldway Elm Bridge-lane Woking Surrey died 18 May 1945. Probate Llandudno 8 September to Marion Tinsley widow. Effects £15,747 5s. 1d.”

His age at the time of death is given as 73 in the General Register Office’s index to deaths (June 1945 quarter, Surrey N.W., 2a, 425).

His death was briefly noted in The Times of 19 May 1945, page 1:

“Tinsley – On 18 May 1945, at Fieldway, Woking, after a short illness, Samuel Tinsley passed peacefully away.”’

8803. Mate after six more moves

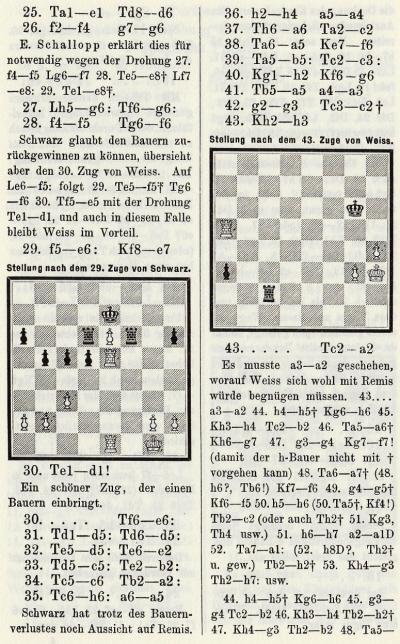

This is one of the most difficult quiz questions that we have set:

White to play. Which of his pieces administered mate six moves later?

8804. Beauty and thought

From an otherwise blank page at the start of Queen’s Gambit and other Close Games by L. Pachman (London, 1963):

The remark is also attributed to Tarrasch in other books by the same author, and elsewhere in chess literature, but in most sources it is ascribed to Nimzowitsch as a riposte to Tarrasch. From page 154 of Nimzovich the hypermodern by Fred Reinfeld (Philadelphia, 1948):

When did the particular wording ‘The beauty of a chess move lies not in its appearance, but in the thought behind it’ first appear in print?

Nimzowitsch wrote about ‘bizarre’ and ‘ugly’ moves on page 229 of Die Praxis meines Systems (Berlin, 1930). His text is shown below, together with the translation on page 329 of The Praxis of My System (London, 1936):

A detailed account of the Tarrasch-Nimzowitsch disputes is provided in Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 by Per Skjoldager and Jørn Erik Nielsen (Jefferson, 2012).

8805. Reinfeld and Nimzowitsch

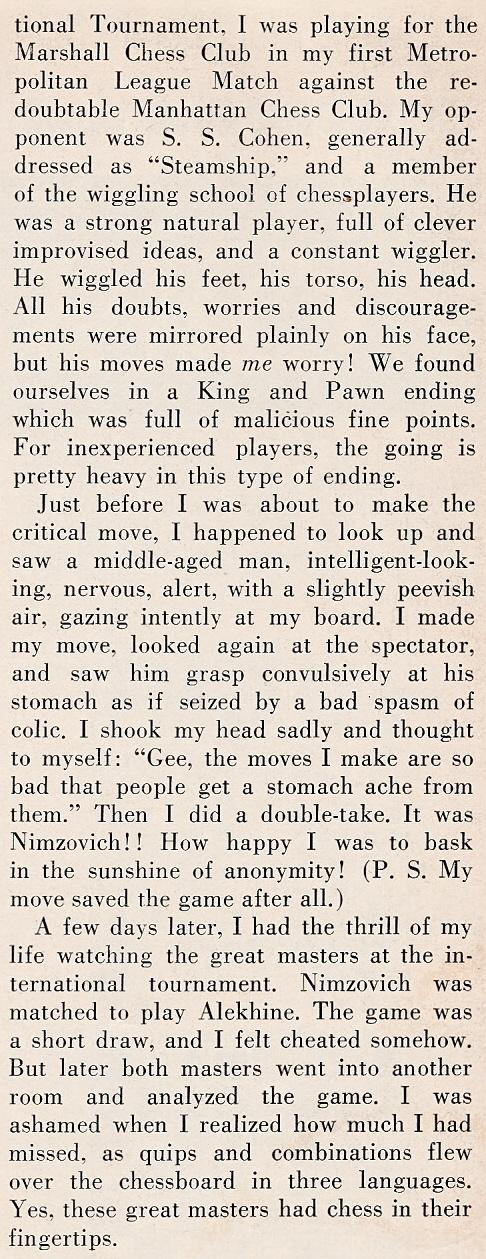

In an article presenting his new edition of Nimzowitsch’s My System Fred Reinfeld wrote on page 208 of the July 1949 Chess Review:

Can information be found about Reinfeld’s game against Cohen?

Reinfeld also mentioned his visit to the New York, 1927 tournament on page 161 of The Great Chess Masters and Their Games (New York, 1952), in the chapter on Capablanca:

‘The other masters were so clearly outclassed that comparison was piteous. I attended the tournament one day to catch a glimpse of the grandmasters. Capablanca looked sleek, poised, quite sure of himself. The others were fearfully nervous – Sorcerer’s Apprentices, all of them, in the presence of the master magician. In any other man, Capablanca’s air of assurance would have made a distasteful impression – but not in his case: he looked so distinguished, so authentically a great man, that the predominant reaction was one of awe.’

8806. Masters’ comments on each other

From the same Chess Review article by Reinfeld referred to in the previous item:

‘... the great masters are downright cruel to each other in the constant fury of their competitive fervor, so that (conservatively) 97% of what they say about each other may safely be tossed into the trash basket.’

8807. Willaert v O’Kelly

Wanted: information about a game between Robert Willaert and Albéric O’Kelly de Galway whose conclusion was on pages 145-148 of How to Play Chess Like a Champion by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

1...g6 2 Qf7 Ne6

3 Rd8 Qc1+ 4 Kh2 Qf4+ 5 Kh3 Resigns.

No particulars about the occasion were provided by Reinfeld, or by Michel Wasnair and Michel Jadoul when they gave the finish, with a credit to Reinfeld, on page 189 of their 1988 book Histoire des maîtres belges.

8808. Mate after six more moves (C.N.

8803)

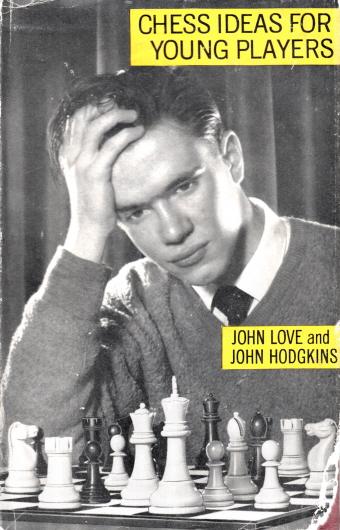

An old game:

1 e3 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 d4 c5 5 Nf3 Nc6 6 a3 a6 7 dxc5 Bxc5 8 b4 Ba7 9 cxd5 exd5 10 Bb2 O-O 11 Bd3 Bg4 12 Ne2 Bxf3 13 gxf3 b5 14 Rc1 Rc8 15 Rg1 Qe7 16 Bf5 Rc7

This is the position from C.N. 8803, which had the caption, ‘White to play. Which of his pieces administered mate six moves later?’

The answer is that on move 22 White gave mate with the rook which at present is on c1.

Before details of the game are supplied, can readers work out how the mate occurred?

| First column | << previous | Archives [121] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.