Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [122] | next >> | Current column |

8809. Prokofiev v Edward Lasker

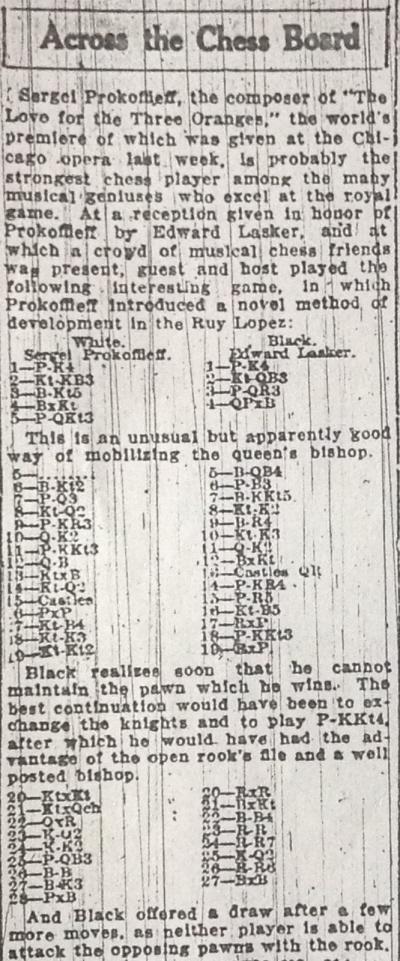

Eduardo Ramirez (Chicago, IL, USA) sends a game between Sergei Prokofiev and Edward Lasker which he found in the Chicago Daily News, 9 January 1922:

Our correspondent has posted the game on his website (A Chess Reader), noting that the score was garbled by the newspaper. Below is an attempt to repair it:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Bxc6 dxc6 5 b3 Bc5 6 Bb2 f6 7 d3 Bg4 8 Nbd2 Ne7 9 h3 Bh5 10 Qe2 Ng6 11 g3 Qe7 12 Qf1 Bxf3 13 Nxf3 O-O-O 14 Nd2 h5 15 O-O-O h4 16 gxh4 Nf4 17 Nc4 Rxh4 18 Ne3 g6

19 Ng2 Rxh3 20 Nxf4 Rxh1 21 Nxg6 Rxf1 22 Nxe7+ Bxe7 23 Rxf1 Bc5 24 Kd2 Rh8 25 Ke2 Rh2 26 c3 Kd7 27 Bc1 Rh3 28 Be3 Bxe3 29 fxe3. The game was agreed drawn a few moves later.

8810. Mate after six more moves (C.N.s 8803 & 8808)

The conclusion was 17 Qxd5 Re8 18 Rxc6 Nxd5 19 Bxh7+ Kh8 20 Bxg7+ Kxh7 21 Rh6+ Kg8 22 Rh8 mate.

The game, won by Friedrich Palitzsch in a simultaneous exhibition against an unnamed opponent in Ölsnitz im Erzgebirge on 28 July 1923, was taken from pages 76-77 of Palitzsch’s book Am Sprudelnden Schachquell 1876-1926 (Berlin and Leipzig, 1926).

From opposite page 126:

The game-score was also published on page 126 of Schnell Matt! by Claudius Hüther and Ludwig Bachmann (Leipzig, 1924) and, as pointed out by Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France), on page 38 of the February 1924 Deutsche Schachblätter, taken from the Dresdener Anzeiger.

8811. Blindfold game by Palitzsch

Pages 85-86 of the Palitzsch book mentioned in the previous item had this game from a six-board blindfold display:

Friedrich Palitzsch – N.N.

Löbau, 16 February 1924

Petroff Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nc3 d5 4 exd5 Nxd5 5 Bc4 c6 6 Nxe5 Qf6 7 d4 Bb4 8 O-O Bxc3 9 bxc3 O-O 10 Bxd5 cxd5 11 f4 Nc6 12 Rb1 Qd8 13 Ba3 Re8 14 Qh5 g6 15 Qh6 Re6 16 Rf3 Rf6

17 Rxb7 Nxe5 18 dxe5 Ra6 19 Be7 Qe8 20 f5 Bxf5 21 Rxf5 gxf5 22 Qxa6 Rb8 23 Qh6 Rxb7 24 Qg5+ Kh8 25 Bf6 mate.

The annotations by Palitzsch given in the book had been published on pages 92-93 of the April 1924 Deutsche Schachzeitung.

8812. Gebhard v Tarrasch

A third game from Am Sprudelnden Schachquell 1876-1926 by F. Palitzsch (pages 104-106):

Hans Gebhard – Siegbert Tarrasch

Offhand game, Munich, 18 October 1925

Albin Counter-Gambit

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 d4 4 Nf3 Nc6 5 g3 Nge7 6 Bg5 Be6 7 Nbd2 Qd7 8 Bxe7 Bxe7 9 Bg2 O-O-O 10 O-O g5 11 b4 g4 12 b5 Na5 13 Ne1 Nxc4 14 Qa4 Nxd2

15 Bc6 Kb8 16 Bxd7 Rxd7 17 Nd3 Nxf1 18 Rxf1 Rhd8 19 Rc1 Bf5 20 Qa5 Rc8 21 Rc4 Rd5 22 a4 c5 23 Qd2 Rdd8 24 Qf4 Be6

25 Nb2 Ka8 26 a5 h5 27 Qc1 Kb8 28 Qc2 h4 29 a6 hxg3 30 fxg3 Bd5 31 Qf5 bxa6 32 bxa6 Rc6 33 Ra4 c4 34 Nxc4 Bxc4 35 Rxc4 Rxc4 36 Qxf7 Rc7 37 Qb3+ Ka8 38 Qe6 d3 39 exd3 Rxd3 40 Qxg4 Bc5+ 41 Kh1 Rd8 42 h4 Kb8 43 Kg2 Bb6 44 e6 Re8 45 Qe4 Ree7 46 Qe5 Rh7 47 Qd6

47...Bc5 48 Qd8+ Rc8 49 Qd3 Re7 50 Qd5 Rec7 51 h5 Be7 52 Kh3 Rd8 53 Qb3+ Ka8 54 h6 Bg5 55 Qf3+ Kb8 56 Qh5 Bf6 57 Qg6 Rf8 58 g4 Rc3+ 59 Kg2 Bd4 60 Qb1+ Bb6 61 Qb2 Rf2+ 62 Qxf2 Bxf2 63 Kxf2 Kc7 64 g5 Rh3 and Black won.

8813. Loyd quotes

A selection of quotes from Chess Strategy by Samuel Loyd (Elizabeth, 1878):

-

‘A few years ago the problemists represented an insignificant minority, and it would have been difficult to name a dozen composers of acknowledged merit.

Today the art is assuming its proper importance in the chess world as a most fascinating feature and invaluable school of practice. Almost every player has essayed to produce a few problems, and among its votaries we find not only the leading spirits of chess journalism, and the finest players of the day, but the main supporters and contributors to every chess publication or enterprise that is undertaken.’ (page 6)

-

‘It is a great mistake to consider it a weakness for a problem to commence with a check. Some of the most brilliant and difficult tournament problems extant consist of a series of checks, and in many positions we will find that a check is the most unpromising move that could be made, and is therefore brilliant and difficult.’ (page 18)

-

‘I have devoted considerable time to cutting down my longer productions to within five moves, which I consider the extreme limit of a common sense problem. Problems in excess of this number are only excusable when there are very few pieces, and the positions are intended to illustrate some pleasing and simple trick.’ (page 37)

-

‘The only thing that I dislike more than a problem in over five moves is a poor one in two.’ (page 37)

-

‘The real merit and science of the feature of difficulty is best shown when embodied in the theme – in the actual moves made, and not in the mere perplexities of the situation. This I will explain by first laying it down as an axiom that a difficult move is one that gives the least apparent promise of the desired result. When a position contains an elegant and scientific theme, with the pieces well posed so as to give no indications of their object, the solver is compelled to form the combination in his mind, much as if he were composing a problem.’ (page 203)

-

‘My entire work has been devoted to an elucidation of the standpoint that beauty and merit are best defined as difficulty produced with the least possible number of pieces.’ (page 234)

-

‘I do not think that players who are not problemists appreciate the benefits derived from the practice of solving. It imparts a spirit of ingenuity, quickness, correctness, and a clear insight of complicated positions that can be acquired in no other way.’ (page 246)

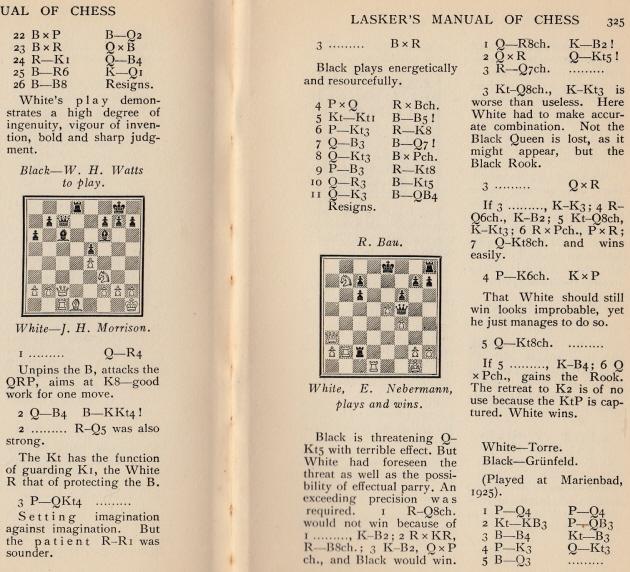

8814. Two positions published by Lasker

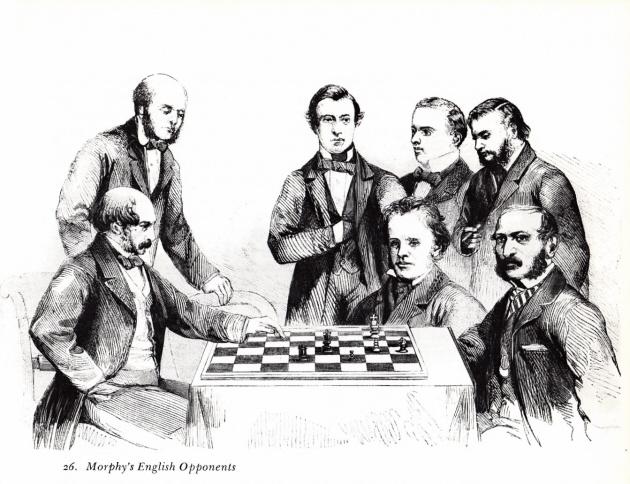

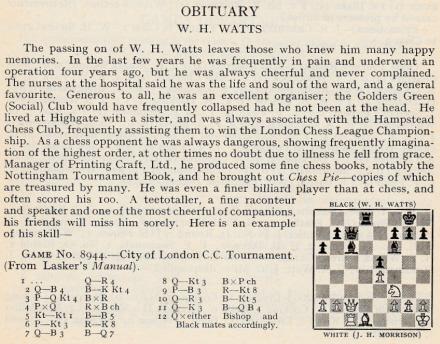

Concerning two positions on pages 324-325 of Lasker’s Manual of Chess (London, 1932), Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) asks where and when they occurred.

W.H. Watts was the publisher and sub-editor of the 1932 edition of the Manual. The first edition (New York, 1927) did not have the Morrison v Watts game, and it is also absent from the German editions that we have consulted.

A possible lead is that Watts defeated Morrison in the 1924-25 Christmas Congress in London (as shown by the crosstable on page 68 of the February 1925 BCM). At the time, Watts was the Editor of the Chess Budget. Our run of that periodical begins later in 1925, and it will be appreciated if a reader can check whether Watts gave his win over Morrison in one of the first issues published that year.

Even less can be suggested at present about the Nebermann v Bau game. German chess magazines of the early twentieth century occasionally mentioned a player named E. Nebermann in Berlin, one instance being on page 65 of Deutsches Wochenschach, 14 February 1904.

8815. August Konrad Haida at Marienbad, 1925

Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987) records that August Konrad Haida was born in Česká Lípa on 6 July 1887 and died circa 1940. David Clayton (Croydon, England) asks for further biographical details about Haida and, in particular, an explanation of his participation in Marienbad, 1925. Page 13 of the tournament book attributed Haida’s modest performance to rustiness but also referred to his brilliant win over Przepiórka, which, the following page noted, received a prize.

Karel Mokrý (Prostějov, Czech Republic) adds that the Czech magazines of 1925, Časopis Československých Šachistů and Soukup’s Šachový svĕt, do not explain Haida’s participation in Marienbad, 1925. The former merely stated that it was Haida’s first strong event and that he was possibly a better player than his result indicated. Mr Mokrý also points out the entry for Haida on page 119 of Malá encyklopedie šachu by J. Veselý, J. Kalendovský and B. Formánek (Prague, 1989), which stated that he was German, a postal clerk in Brno and a master of the ÚJČŠ (Czechoslovak Chess Union) as from 1921.

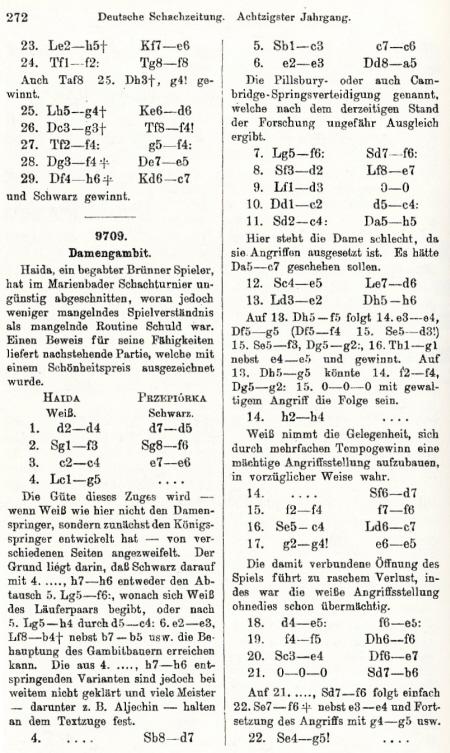

For the group photograph of Marienbad, 1925 see C.N.s 5119 and 5125. Haida’s victory over Przepiórka was published on pages 272-273 of the September 1925 Deutsche Schachzeitung, with Réti’s notes from the Morgenzeitung:

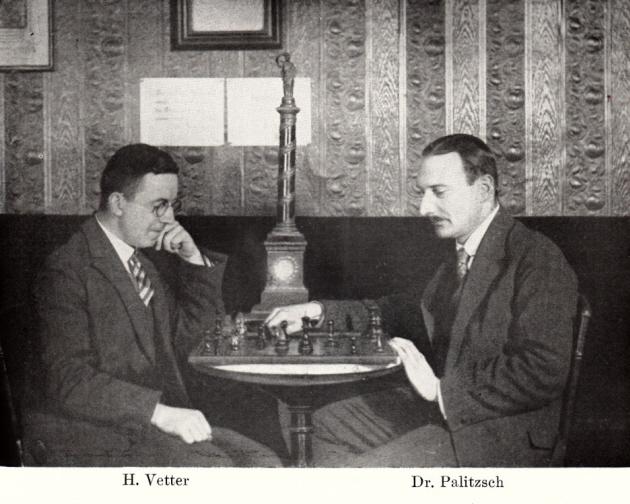

8816. Friedrich Palitzsch (C.N. 8810)

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) reports that a webpage of the Cleveland Public Library has a photograph of Palitzsch on a postcard which he sent to Alain C. White in 1911.

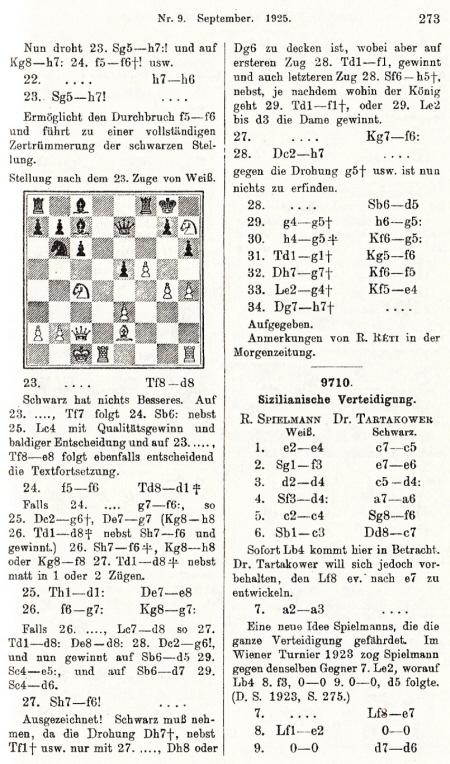

8817. Morphy’s opponents (C.N. 8705)

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) suggests, very tentatively, this caption (from left to right): T.W. Barnes, G. Walker, S.S. Boden, A. Mongrédien, H.E. Bird, R.W. Wormald and J.J. Löwenthal.

8818. ‘The threat is stronger than the execution’

In all the citations of the phrase ‘the threat is stronger than the execution’, whether or not connected to the smoking anecdote, a name not seen so far is Capablanca. However, we now add a ‘once’ version on page 200 of a book by W. Ritson Morry and W. Melville Mitchell, which, as mentioned in C.N. 8818, was published in the 1960s and 1970s under a range of titles (Chess: A Way to Learn; Chess The Elements and the Play; Tackle Chess This Way; Tackle Chess; Chess Theory and Practice):

‘Dr Vidmar once promised to refrain from smoking in a game with Nimzowitsch, but in mid-session the latter approached the controller very agitatedly saying “You remember Vidmar promised not to smoke?” “Yes”, replied the controller. “But he isn’t.” “Ah”, came the reply, “but he looks as if he wants to, and you know that Capablanca said a threat is stronger than its execution.”’

8819. Indian openings

Tony Gillam (Nottingham, England) asks why the term ‘Indian’ is used in chess opening nomenclature.

We have decided to tackle the matter broadly by also seeking the earliest appearance of ‘Indian’ in the names of individual openings, as well as the first occurrence of the moves themselves. A basic framework has been created in the form of a draft feature article, Indian Openings in Chess. Information will be added gradually, beginning with citations which have already appeared in C.N. (See, for instance, the references to the Nimzo-Indian Defence in the Factfinder.)

Readers are invited to make proposals and, as ever in such cases, to do so without apprehension. Only the ‘best’/oldest citations will be added to the feature article.

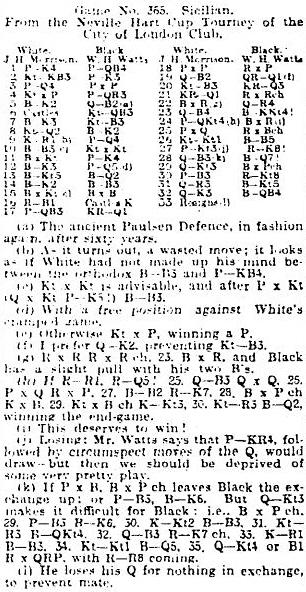

8820. Morrison v Watts (C.N. 8814)

The conclusion of Watts’ win against Morrison was also given in his obituary on page 37 of the February 1942 BCM:

Alan Smith (Stockport, England) has found the full game in Brian Harley’s column in the Observer, 28 November 1926 (page 27), which stated that the occasion was ‘the Neville Hart Cup Tourney of the City of London Club’:

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 a6 5 Be2 Qc7 6 O-O Nc6 7 Be3 Nf6 8 Nd2 Be7 9 Kh1 d5 10 Bf3 Nxd4 11 Bxd4 e5 12 Be3 d4 13 Bg5 Bd7 14 Be2 Bc6 15 Bxf6 Bxf6 16 Rc1 O-O 17 c3 Rfd8 18 cxd4 Rxd4 19 Qc2 Rad8 20 Nf3 R4d6 21 Rfd1 Rxd1+ 22 Bxd1 Qa5 23 Qc4 Bg5 24 b4 Bxc1 25 bxa5 Rxd1+ 26 Ng1 Bf4 27 g3 Re1 28 Qc3 Bd2 29 Qb3 Bxe4+ 30 f3 Rb1 31 Qa3 Bb4 32 Qe3 Bc5 33 White resigns.

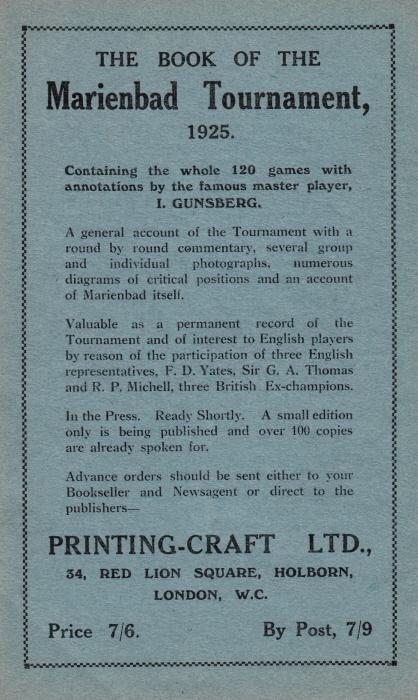

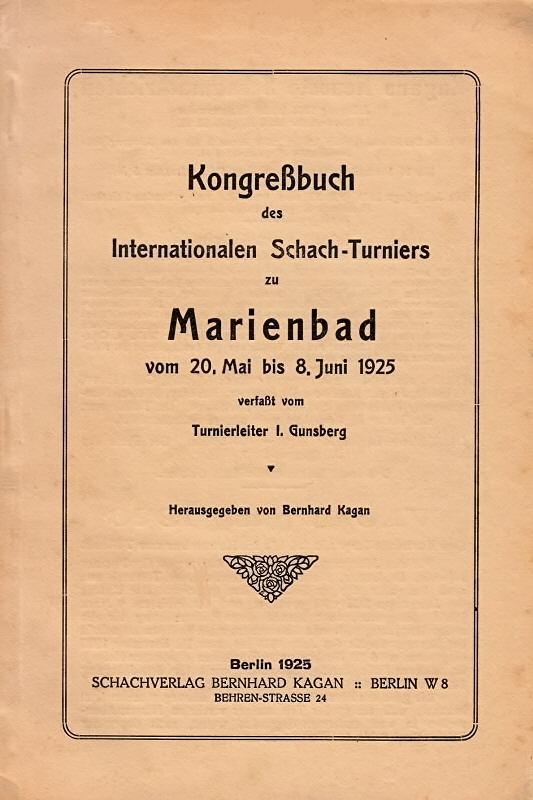

8821. Marienbad, 1925 (C.N. 8815)

Many issues of W.H. Watts’ magazine the Chess Budget in 1925-26 had this full-page advertisement on the back cover:

There was also a notice on page 378 of the September 1925 BCM, but the book by Gunsberg appears to exist only in the German edition mentioned in C.N. 8815:

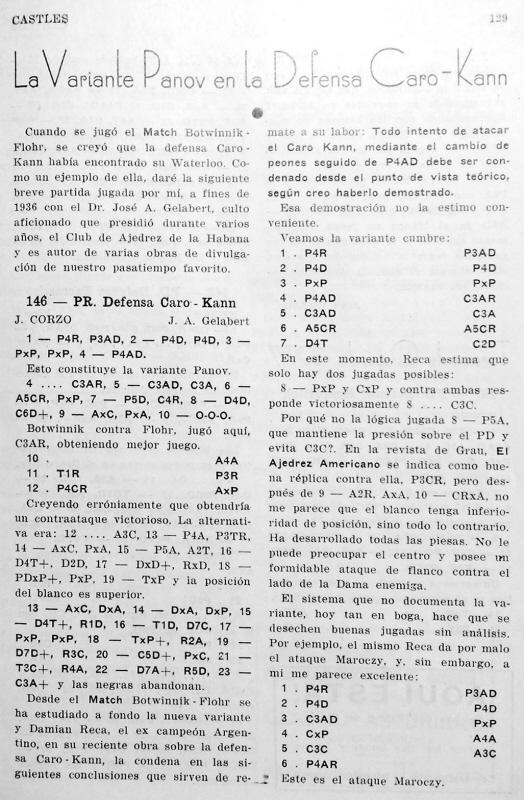

8822. Corzo v Gelabert

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) forwards a game (Havana, 1936) between Juan Corzo and José Antonio Gelabert which the former published on page 129 of the 8/1937 issue of the Argentinian magazine Castles:

1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 exd5 cxd5 4 c4 Nf6 5 Nc3 Nc6 6 Bg5 dxc4 7 d5 Ne5 8 Qd4 Nd3+ 9 Bxd3 cxd3 10 O-O-O Bf5 11 Re1 e6 12 g4 Bxg4 13 Bxf6 Qxf6 14 Qxg4 Qxf2 15 Qa4+ Kd8 16 Rd1 Qg2

17 dxe6 fxe6 18 Rxd3+ Kc7 19 Qd7+ Kb6 20 Nd5+ exd5 21 Rb3+ Kc5 22 Qc7+ Kd4 23 Nf3+ Resigns.

8823. Prokofiev v Edward Lasker (C.N. 8809)

Edward Lasker wrote about Prokofiev and their meeting in Chicago on pages 199-201 of The Adventure of Chess (New York, 1950).

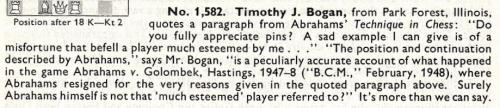

8824. Gerald Abrahams

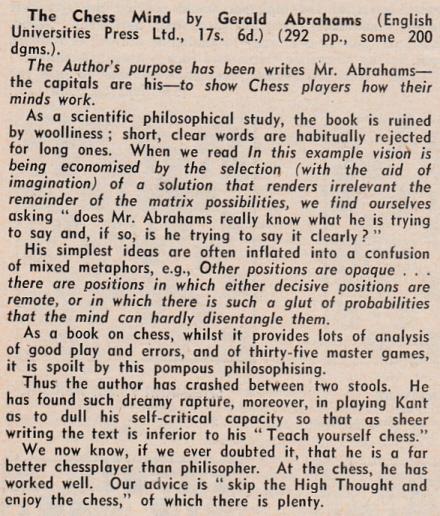

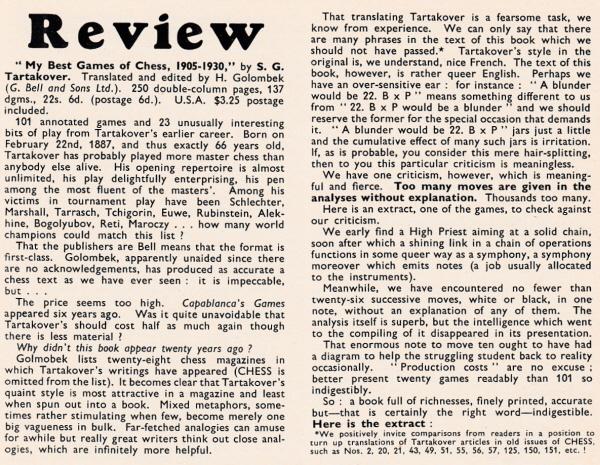

Improbable as it may seem today, CHESS often used to adopt a critical, demanding attitude to new books. For example, below is a review of The Chess Mind by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1951) on page 118 of the March 1952 issue of B.H. Wood’s magazine:

In contrast, The Chess Mind was received positively by J.M. Aitken on pages 12-13 of the January 1952 BCM. The first paragraph:

‘This work breaks fresh ground in chess literature. It is not a textbook on the game, though much of the book, particularly the numerous examples, would be interesting and instructive from this angle, too, to the player of some experience, though not the absolute tyro; it is a study of what happens when chessplayers (more particularly the chess masters) think. The subject is by its very nature not an easy one to analyse and expound; hence the book necessarily deserves – and repays – concentrated attention; but the style does not – as in some hands it might have done – add to the inherent difficulties. It is throughout light, racy and frequently aphoristic, and is mercifully free from any suspicion of philosophic jargon.’

Fred Reinfeld was even more enthusiastic on page 182 of How To Get More Out Of Chess (New York, 1957):

‘The Chess Mind, by Gerald Abrahams, is to my way of thinking one of the very best, and certainly one of the most original, books ever written on chess. Of making chess books there is no end, but few are as meaty and brilliantly written as this one. Such chapters as Vision in Chess; Common Sense and the Intrusion of Ideas; Imagination: Its Use and Abuse; How Battles are Won and Lost are unique in chess literature. One of the finest books ever written on chess.’

The Chess Mind subsequently appeared in paperback editions, widely and inexpensively available today from second-hand booksellers.

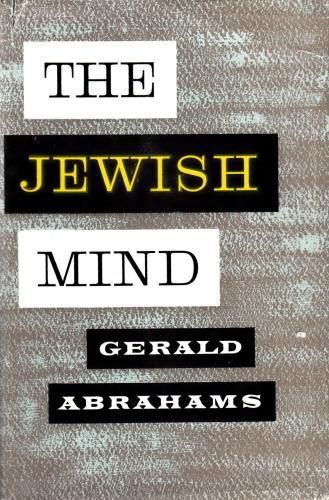

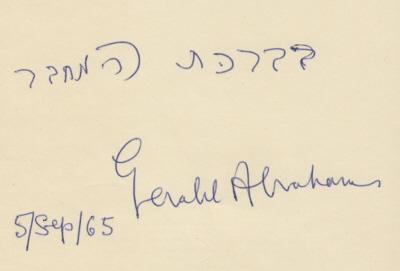

As mentioned in Chess and the Wallace Murder Case, Abrahams also wrote The Legal Mind (London, 1954). He was, furthermore, the author of The Jewish Mind (London, 1961), and our collection includes a copy inscribed by him:

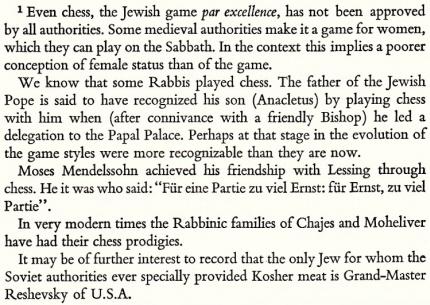

The Jewish Mind has a few references to chess in the footnotes, including the following on page 354:

8825. Ettlinger v Capablanca

Page 101 of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975) gave the conclusion of a game between A. Ettlinger and Capablanca (New York, 1907):

1...Nc4 2 Nxc4 dxc4 3 Rxc4 Kd5 4 Rc8 Ke4 5 Re8+ Kd3 6 Rxe2 fxe2+ 7 Ke1 Bc7 8 Bf4 Ba5 9 Bd2

9...f4 10 gxf4 Bd8 11 White resigns.

The book quoted some remarks by Emanuel Lasker and specified, on page 200, that the source was the New York Evening Post, 17 April 1907.

Below (barely legible, alas) is that column of Lasker’s in the Evening Post (page 6), as well as the correction published on page 7 of the following day’s edition:

The full game-score has not been found. The finish is seldom seen in chess literature, although it was discussed on page 78 of Surprise in Chess by Amatzia Avni (London, 1998).

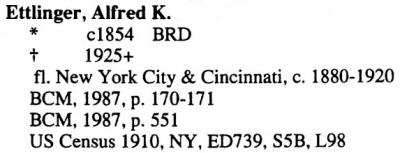

There are brief references to Alfred K. Ettlinger in our book on Capablanca. See too pages 170-171 of the April 1987 BCM and page 551 of the December 1987 issue.

8826.

Bibliographies and sources (C.N. 8110)

In C.N. 8110 a correspondent gave many examples of the trend towards citing inferior websites in bibliographies. The most dismal case that we have seen is the ‘Sources Used’ list on pages 161-162 of Anand-Gelfand Moscow 2012 by Dániel Lovas (Kecskemét, undated).

The ‘Sources of further quotations, commentaries’ section includes ‘Susan Polgar Chess Daily News and Information – susanpolgar.blogspot.com’ and, even, ‘Twitter – twitter.com’.

8827. More on bibliographies

Immediately following publication of Bent Larsen’s Best Games (Alkmaar, 2014) Timothy J. Bogan (Chicago, IL, USA) wrote to us:

‘On the page I opened at random on first picking up the book I read in the Editor’s Foreword (page 23):

“Larsen’s first best games collection written by himself appeared in 1969 in Denmark and was entitled 50 Udvalgte Partier, 1948-69 (Samlerens Forlag). The English edition was published in 1970 by Batsford as Bent Larsen: Master of Counter-Attack.”

Larsen’s Selected Games of Chess 1948-69 was originally published by Bell in 1970. Bent Larsen: Master of Counter-Attack was the title used in a 1992 Batsford reprint.’

As any random survey of chess bibliographies will show, reprints often result in the provision of confusing information, even when there is no change of title. To take one well-known work:

- 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (two volumes), G. Bell & Sons, Ltd., London, 1952.

- [500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (single volume), David McKay Company, Inc., New York, 1954.]

- 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (single volume), Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1975.

- 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (single volume), B.T. Batsford Ltd., London, 1991.

Any bibliography which lists 500 Master Games of Chess is, of course, at liberty to cite any of these editions, as long as the details are correct and it is specified that the book was first published in 1952. Instead, this kind of thing is offered:

- ‘500 Master Games of Modern Chess (Tartakower and du Mont) Dover, 1975’

- ‘Tartakower, Savielly, and DuMont, Julius. 500 Master Games of Chess. Dover Publications Inc., New York 1975.’

- ‘500 Master Games of Chess, Dumont & Tartakower, Dover 1952’

- ‘Tartakower, S.G. and J. duMont. 500 Master Games of Chess. New York: Dover, 1975’

- ‘500 Master Games of Chess, S. Tartakower & J. Du Mont (Dover 1952)’

- ‘500 Master Games by Savielly Tartakower and Dumont (Dover, 1975)’

- ‘500 Master Games of Chess, S. Tartakower and J. Du Mont (Batsford 1991)’

Page 248 of The Complete Chess Addict by M. Fox and R. James (London, 1987).

Page 371 of Frank Marshall, United States Chess Champion by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 1994).

Page 147 of Winning with Reverse Chess Strategy by W. Reuter (Davenport, 1998).

Page 256 of The 100 Best Chess Games of the 20th Century, Ranked by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 2000).

Page 3 of Play the Ponziani by D. Taylor and K. Hayward (London, 2009).

Page 5 of The Rules of Winning Chess by N. Davies (London, 2009).

Page 6 of Giants of Innovation by C. Pritchett (London, 2011).

Unable to write ‘du Mont’, Soltis wrote him out. From page 93 of The Wisest Things Ever Said About Chess (London, 2008):

The passage cited is on page 55 of Tartakower and du Mont’s book.

8828. Wood on Tartakower and du Mont

Further to C.N. 8824, another example of the approach to chess literature adopted by CHESS is provided on page 138 of the April 1952 magazine (the issue after the one asserting that with The Chess Mind Gerald Abrahams had ‘crashed between two stools’). Reviewing 500 Master Games of Chess, B.H. Wood began by referring to the size of his library:

‘We too find ourselves gazing at new books with a more and more jaundiced eye and are wondering whether our libraries have something to do with it. Have we seen too many chess books? Is originality becoming rarer, or are we only beginning to realize how rare it always was? As we ransack book after book in vain for a spark of real newness and our disappointment mounts into fury, we retain just sufficient self-control to ask “If this were the fifth chess book we had handled instead of the five-thousandth, mightn’t we be enjoying it enormously?”Could the value of a book to the average reader better be assessed – by an average reader? Would you go to a jaded old roué for an opinion on the delights of romance?

Here is a book, 500 Master Games of Chess, written by two old friends whose feelings we hate to hurt, about which we can hardly find a good thing to say. To some it may be a wonderful anthology of the richnesses of the past century and more. To us it is only a laboured rehash of games which have appeared in print before, some of them ten, 20 or 30 times in as many different publications.’

After examining some games and notes Wood continued:

‘... knowing the furious rate of development of theory today, what strong player will pay £2 10s 0d for a collection of 500 games, most of which date from the eighteen hundreds? ...

The extensive proof-reading has been tackled hardily, but we found an inaccuracy or an ambiguity in the text of each of the first three games we played through ...

All in all, a sad waste of time, energy, paper and print. A lamentable acceptance of the idea that 500 elephants or Roman gladiators must be better drama than 50.

That is how we feel about it. Is it only our misfortune? Perhaps! Where ignorance is bliss, ’tis folly to be wise!’

The May 1952 issue (page 160) had brief responses from B. Goulding Brown and J. du Mont, and there was a further short letter from du Mont on page 194 of the July 1952 CHESS. The first of du Mont’s letters read as follows (in full):

‘You state: “What strong player will pay £2 10s for a collection of games most of which date from the eighteen hundreds?”, as damaging a statement as could well be made. The fact is that, of the 500 games 153 come from the pre-1900 period, and no fewer than 347 relate to the years 1900-38 (a further volume covering the period 1938 to the present day is in active and advanced preparation).’

8829. Cartoons and inscriptions (C.N. 8771)

As noted by Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada), the New Year cards (1959 and 1960) were signed by Viascheslav Ragozin.

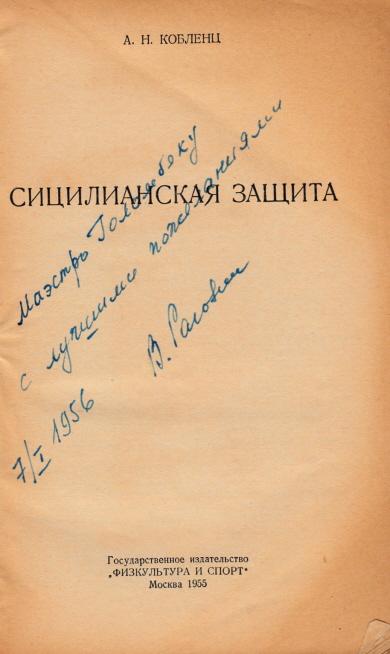

For purposes of comparison, below is the title page of one of our copies of A. Koblentz’s book on the Sicilian Defence, Сицилианская защита (Moscow, 1955), with an inscription by Ragozin to Golombek:

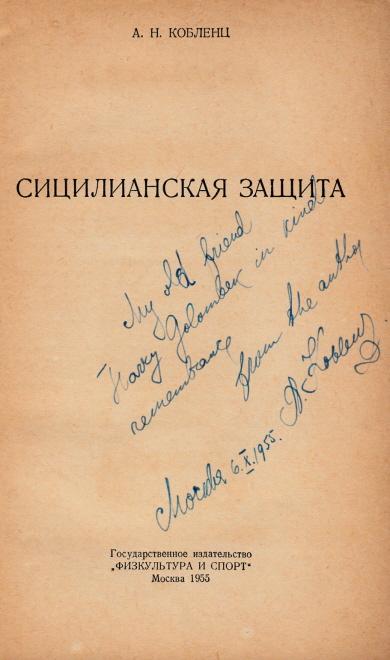

We also have a copy dedicated to Golombek by Koblentz.

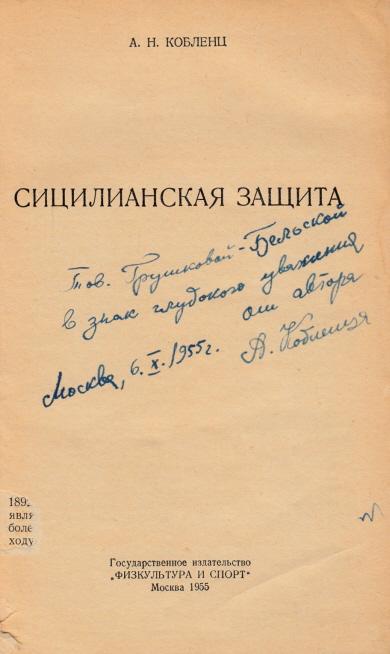

A third copy in our collection was inscribed by Koblentz to Nina Hrušková-Bělská:

8830. Ortueta v Sanz (C.N.s 8153 & 8158)

Regarding the famous, mysterious Ortueta v Sanz game, Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) has just found a chess column in the Tagesbote (Brno) of 14 April 1934 which throws a hefty spanner in the works by giving the conclusion of a game said to have been won in Madrid the previous year by the Swedish player Ored Karlin against an unnamed opponent:

8831. Alfred K. Ettlinger (C.N. 8825)

Page 203 of the unpublished 1994 version of Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia had this entry:

However, Eduardo Ramirez (Chicago, IL, USA) has forwarded the following from page A1 of the Chicago Daily Tribune, 4 January 1920:

8832. White Death

The chess novel White Death by Daniel Blake (London, 2012) has 64 chapters divided into three parts:

How many more times will the nineteenth-century quote be misattributed to Spielmann?

8833. Tactics and strategy

As mentioned in our article Kasparov’s How Life Imitates Chess, the former world champion’s book, written with Mig Greengard, wrongly ascribed the book/magician/machine remark to Spielmann.

Now we give the heading to Chapter 4 in the London, 2007 edition (page 41):

In the US edition (New York, 2007) this ‘Tartakower quote’ is in the heading to Chapter 3, on page 36. But did Tartakower make such a remark and, if so, where and when?

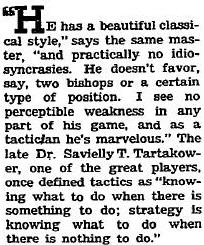

The earliest citation that we can currently offer is nothing better than a ‘once’ reference in an article about Fischer by Harold C. Schonberg on page SM63 of the New York Times, 23 February 1958:

The article was reproduced on pages 49-55 of The Joys of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1961), still with the initial T. for Tartakower’s second forename. Schonberg also ascribed the quote to Tartakower on page 160 of Grandmasters of Chess (Philadelphia and New York, 1972), and it is regularly seen in chess books, without a source. For instance, Gary Lane used it to fill a corner on page 57 of Prepare to Attack (London, 2010).

In his entry on aphorisms on page 16 of The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977) Wolfgang Heidenfeld included the following:

‘“Whereas the tactician knows what to do when there is something to do, it requires the strategist to know what to do when there is nothing to do” (Abrahams).’

Heidenfeld gave no source, but we have found the remark on page 150 of Abrahams’ book Teach Yourself Chess (London, 1948), although with ‘strategian’ instead of ‘strategist’.

Furthermore, the following can be quoted from page 152 of The Handbook of Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1965):

‘At many stages of the game the general choice is available; what to do now that there is no coercion? Epigrammatically, it may be said: Tactics are what you do when there is something to do. Strategy is what you do when there is nothing to do. That isolation, however, is rare. Strategy is a feature, albeit unobserved, of most good tactical play. It is latent – not patent.’

8834. Further jottings on bibliographies

and sources

Two books on the Budapest

Defence show contrasting ways of handling a

bibliography. The Budapest Fajarowicz by Lev

Gutman (London, 2004) has a full page (page 287) of

references to books and articles, but with many misprints

(including an occurrence of ‘Fajarowitz’). The book

section of the bibliography on page 5 of The Budapest

Gambit by Timothy Taylor (London, 2009) lists just

five works, three of them general (by Alekhine, Horowitz

and Kasparov).

The bibliography on pages 5-6 of Play the Ponziani

by Dave Taylor and Keith Hayward (London, 2009) includes

many books, but virtually all of them are recent. Magazine

articles of the kind catalogued in C.N. 7941 are ignored.

The more disorganized a book is, the greater the need for a bibliography, general index and proper sourcing, but none of these can be found in Mannheim 1914 and the Interned Russians by A.J. Gillam (Nottingham, 2014), a 525-page hardback which sorely needed a general editor and an English-language editor.

Another book by Timothy Taylor, True Combat Chess

(London, 2009), has this entry in the bibliography on page

5:

To avoid the risk of such mishaps, one possibility is the

approach adopted by Efstratios Grivas on page 5 of Beating

the

Fianchetto Defences (London, 2006):

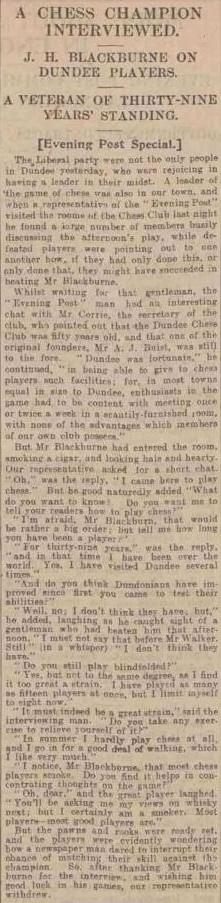

8835. Blackburne in Scotland

From page 3 of the Dundee Evening Post, 16 November 1900:

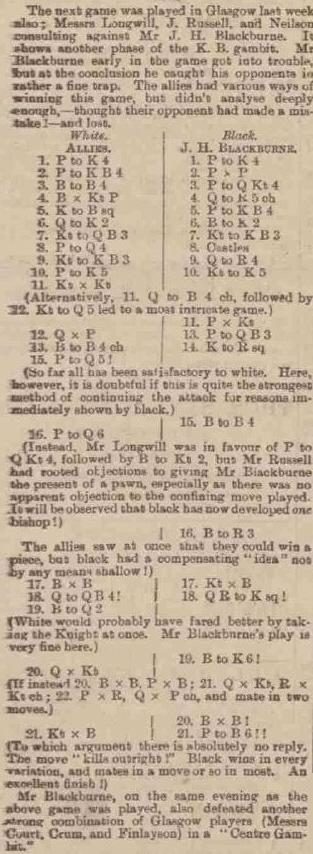

A specimen of Blackburne’s play in Scotland (a victory in Glasgow against J.R. Longwill, J. Russell and A.J. Neilson) was published on page 8 of the Falkirk Herald and Midland Counties Journal, 14 November 1900:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 b5 4 Bxb5 Qh4+ 5 Kf1 f5 6 Qe2 Be7 7 Nc3 Nf6 8 d4 O-O 9 Nf3 Qh5 10 e5 Ne4 11 Nxe4 fxe4 12 Qxe4 c6 13 Bc4+ Kh8 14 d5 Bc5 15 d6 Ba6 16 Bxa6 Nxa6 17 Qc4

17...Rae8 18 Bd2 Be3 19 Qxa6 Bxd2 20 Nxd2

20...f3 and wins.

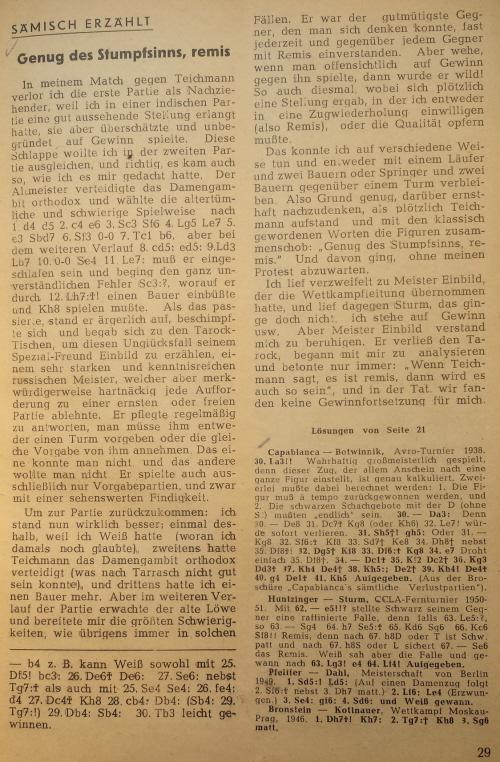

8836. ‘Genug des Stumpfsinns, Remis!’ (C.N.s 8437 & 8449)

Concerning the remark ‘Genug des Stumpfsinns, Remis!’ (‘Enough tedium, draw!’) attributed to Richard Teichmann, Birger Flindtholt (Randers, Denmark) has found the following (Caïssa, January 1952, page 29):

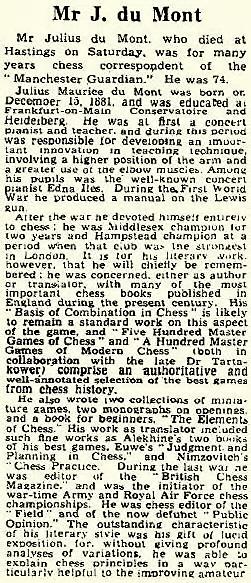

8837. Obituary of Julius du Mont

Below is the obituary of Julius du Mont on page 4 of the Manchester Guardian, 9 April 1956:

8838. Steinitz versus God

The matter of Steinitz versus God has even been mentioned in prominent reference book. Below is the final sentence of the brief entry on Steinitz on pages 1392-1393 of the Chambers Biographical Dictionary edited by Magnus Magnusson (Edinburgh, 1990):

‘He died, impoverished, in a New York mental asylum following an unsuccessful attempt to challenge God to a chess match.’

8839. Wood on Tartakower

Following on from B.H. Wood’s critiques of The Chess Mind (C.N. 8824) and 500 Master Games of Chess (C.N. 8828), we show his review of My Best Games of Chess 1905-1930 by S.G. Tartakower (London, 1953), on page 113 of the March 1953 CHESS:

The extract referred to (given on pages 113-116) was the game Tartakower v Schlechter, St Petersburg, 1909.

8840. The consultation game that never was

Although it has been known for decades that the Janowsky/Soldatenkov v Lasker/Taubenhaus consultation game (Danish Gambit) did not occur among these players, it receives three full pages (pages 148-150) in Chess for Rookies by Craig Pritchett (London, 2009). It is described as an ‘exhibition game’, and Lasker’s supposed partner is named as ‘Tabenhaus’.

8841. Victory by James Rivkin over Capablanca

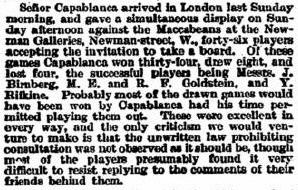

From page 1 of the sports section of the Chicago Daily Tribune, 26 December 1925:

The game occurred in the simultaneous exhibition mentioned on page 99 of the January 1926 Chess Amateur:

‘Señor Capablanca, who left London for Havana on Monday, 14 December, gave a monster simultaneous display on the previous afternoon at the Maccabaeans Club, Oxford Street. He contested 56 games, winning 34, losing four and drawing ten, eight games being left unfinished after four hours’ play. One of the winners was a Russian boy of 15, named Rivkine.’

The January 1926 BCM (page 25) reported a different score:

‘Of the hundred or more players anxious to take a board, the limit was reached when 46 were seated: a wise decision, as only four and a half hours were available for play. The Cuban moved with his usual ease and rapidity, and the display was nearing its end when a group of spectators gathered round the young Russian Rifkine were heard to sound an alarm, which culminated in a cheer, announcing the Champion’s first defeat (by the youngest of his opponents). Shortly after, the remaining eight or ten games were adjudicated, and Capablanca conceded three wins, to J. Birnberg, M.E. Goldstein and R.F. Goldstein respectively. The final figures were 34 wins, eight draws and four losses.’

That tally corresponded to what had appeared on page 8 of the Times Literary Supplement, 17 December 1925, which had a reference to Y. Rifkine:

A photograph of the display was published on page 18 of the Times, 14 December 1925:

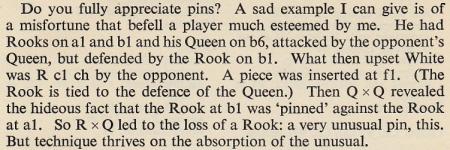

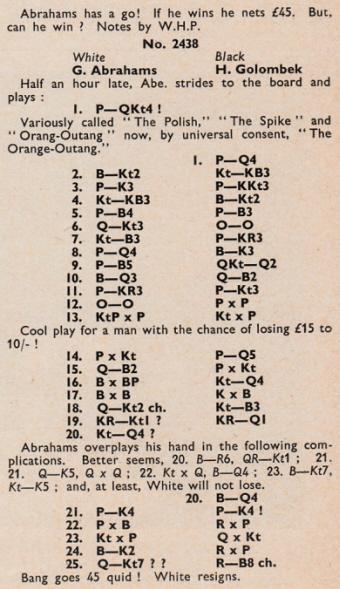

8842. A much esteemed player

From page 215 of Technique in Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1961):

The passage was referred to in D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column on page 303 of the October 1965 BCM:

There was also a brief reference on page 359 of the December 1965 BCM.

Below is the finish as given on page 57 of the BCM, February 1948:

The game was ‘annotated’ by W.H. Pratten on page 121 of the February 1948 CHESS:

Although sometimes dated 1947, the game was played on 6 January 1948, as reported on page 7 of the Times the following day.

8843. 1 b4

A surprising passage from pages 292-293 of Modern Chess Opening Traps by William Lombardy (New York, 1972):

‘Orangutan Opening

This opening, named after a gangling ape, was so dubbed at a time when 1 P-K4 and 1 P-Q4 were thought to be the only normal and therefore the only satisfactory debuts. Today such grandmasters as Pal Benko, Bent Larsen and William Lombardy have brought the opening into true prominence so that 1 P-QN4 may be considered as regular as any other opening. The obvious theme is the early attempt to gain a central pawn for a flank pawn, an exceptionally good bargain.’

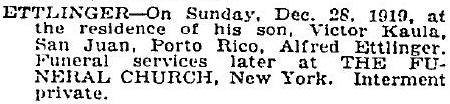

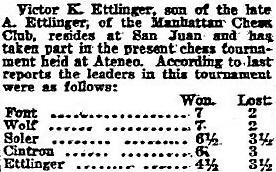

8844. Alfred K. Ettlinger

Larry Crawford (Milford, CT, USA) notes that Alfred K. Ettlinger’s death was listed on page 7 of the New York Times, 31 December 1919 with an exact date and place: 28 December 1919 in San Juan.

Mr Crawford also draws attention to Ettlinger’s headstone.

We add that the father and son were mentioned on page 5 of the Philadelphia Inquirer, 5 June 1921:

Alfred K. Ettlinger appears in the background of a photograph taken during the New York, 1918 tournament (C.N. 3980).

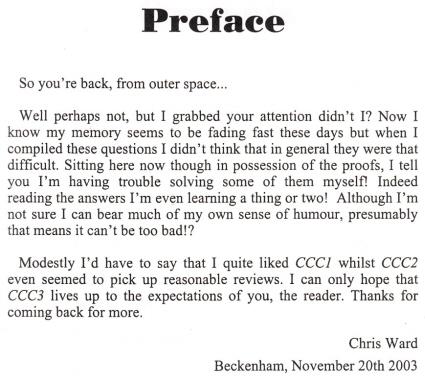

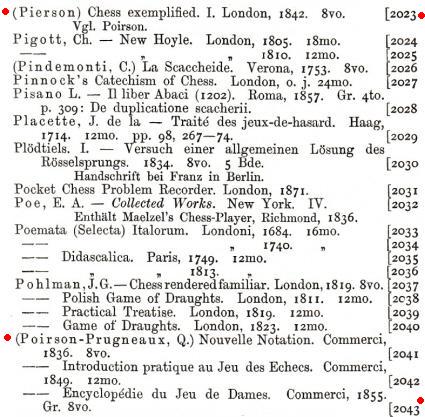

8845. Chess Exemplified

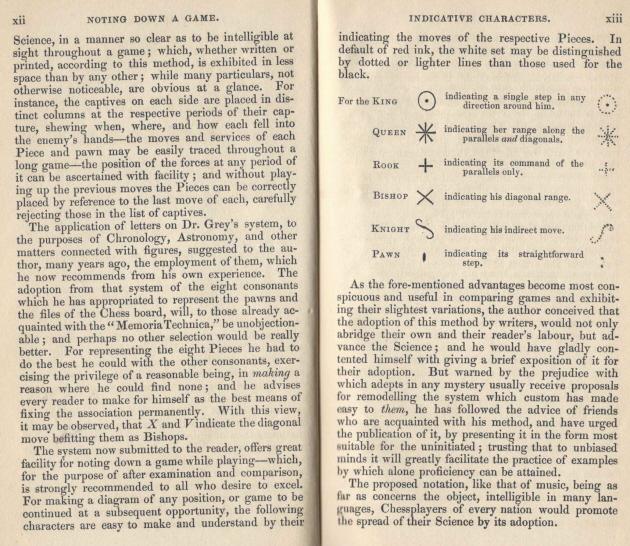

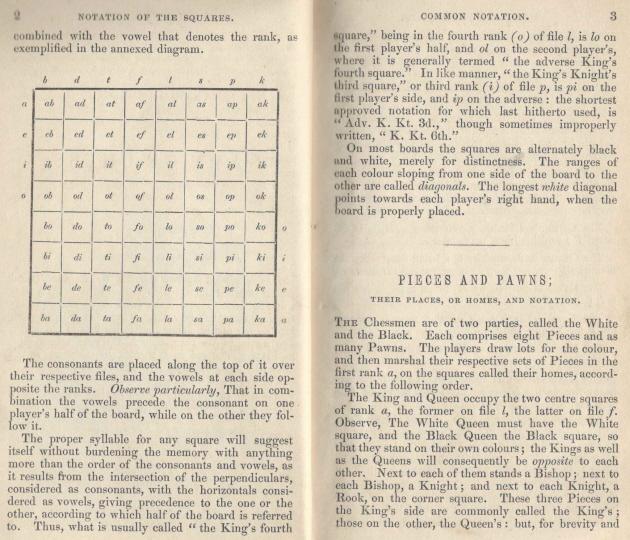

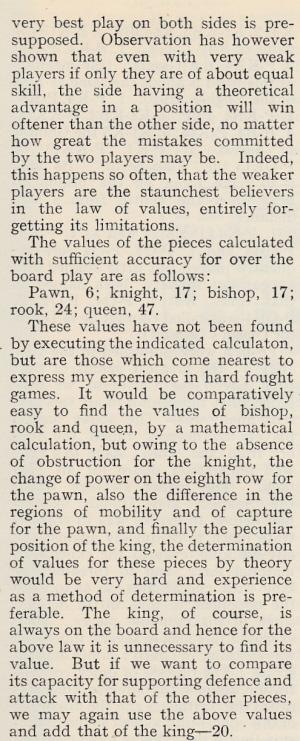

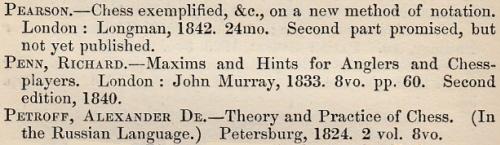

John Roycroft (London) seeks information about the author of a 128-page book which he owns, Chess Exemplified (London, 1842).

The above sample pages have been provided by our correspondent, who comments:

‘In the decade before Horwitz and Kling’s Chess Studies the erudite author, who writes very well indeed, devotes nearly the whole of his work to the endgame.’

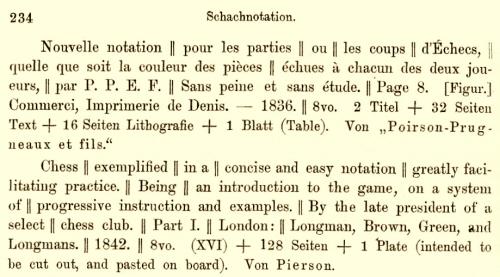

Wanted: particulars about the author, beyond the information (with bare references to Poirson and Pierson) on page 234 of volume two of Geschichte und Litteratur des Schachspiels by A. van der Linde (Berlin, 1874):

8846. Szabó v Roycroft

Simultaneous games played by readers are always welcome, and John Roycroft refers to his encounter, at the age 18, with Szabó in a 19-board display at the Gambit Chess Rooms, 4 Budge Row, London:

László Szabó – Arthur John Roycroft

London, 10 January 1948

Nimzo-Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 a3 Bxc3+ 5 bxc3 c5 6 e3 d5 7 cxd5 Nxd5 8 c4 Nf6 9 Nf3 O-O 10 Bd3 b6 11 O-O Bb7 12 Bb2 Nbd7 13 Qe2 Be4 14 Bxe4 Nxe4 15 Rfd1 Qc7 16 d5 exd5 17 cxd5 Qd6 18 Ne1 Rfe8 19 f3 Nef6 20 e4 Rac8 21 Rac1 h6 22 Qc4 Ne5 23 Bxe5 Qxe5 24 Nd3 Qb8 25 e5

25...b5 26 Qa2 c4 27 exf6 cxd3 28 Rxc8 Rxc8 29 Qb3 Qb6+ 30 Kh1 Qd4 31 h3 d2 32 Qb1 Qe3 33 d6 Rc1 34 d7 Rxd1+ 35 Qxd1

35...Qe1+ 36 Kh2 Qe5+ 37 Kg1 Qd4+ 38 Kf1 Qxd7 39 fxg7 Qd3+ 40 Kf2 Kxg7 41 f4 f5 42 Qa1+ Kf7 43 Qd1 Ke6 44 g4 fxg4 45 hxg4 Kd5 46 g5 Ke4 47 gxh6 Kxf4 48 h7 Qg3+ 49 Ke2 Qe3+ 50 Kf1 Qf3+ 51 Qxf3+ Kxf3 52 White resigns.

Our correspondent included the game, together with a photograph of the occasion, in his article ‘London Chess Haunts of the 1940s and 1950s’ on pages 30-33 of CHESS, May 1995.

8847. Ortueta v Sanz (C.N.s 8153, 8158 & 8830)

Zalmen Kornin (Curitiba, Brazil) draws attention to a report on page 46 of ABC, 24 May 1933, which announced a tournament in Madrid with the participation of, inter alios, Karlin, Sanz and Ortueta.

8848. The erstwhile art of chess annotation

On pages 70-71 of the February 1972 BCM Wolfgang Heidenfeld reviewed the magazine’s reprint of the Coburg, 1904 tournament book edited by P. Schellenberg, C. Schlechter and G. Marco. The annotations of Marco (‘as famed an analyst as a stylist’) were singled out for praise and the review concluded:

‘Such books are refreshing – and indeed very necessary – at a time when the erstwhile art of chess annotation has been reduced to an almost computerized routine, with mechanized symbols replacing the individual approach. The mass production era, with its demand on the reader’s time and the writer’s space, may make such mechanization inevitable – those of us who still enjoy a “well-spoken game of chess” will nevertheless deplore this development. It is to them that Coburg, 1904 will mean more than the record of a not very distinguished tournament.’

8849. Without comment

Source: page 3 of Chess Choice Challenge 3 by Chris Ward (London, 2004). The publisher was B.T. Batsford Ltd.

8850. Chess Exemplified (C.N. 8845)

From page 79 of Das Erste Ja[h]rtausend der Schachlitteratur (850-1880) by A. van der Linde (Berlin, 1881):

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘An entry dated 20 August 1842 in the copyright register at the National Archives (COPY 3/1, page 19) identifies the proprietor of Chess Exemplified as Charles Pearson, of Maize Hill, Greenwich.

The 1841 census (National Archives, HO 107/489/5, ff. 23-24) finds him at Maize Hill, Greenwich. He is described as being of independent means and in the age-range 55-59. With him were his wife and several children, including a son, Charles, who was a solicitor.

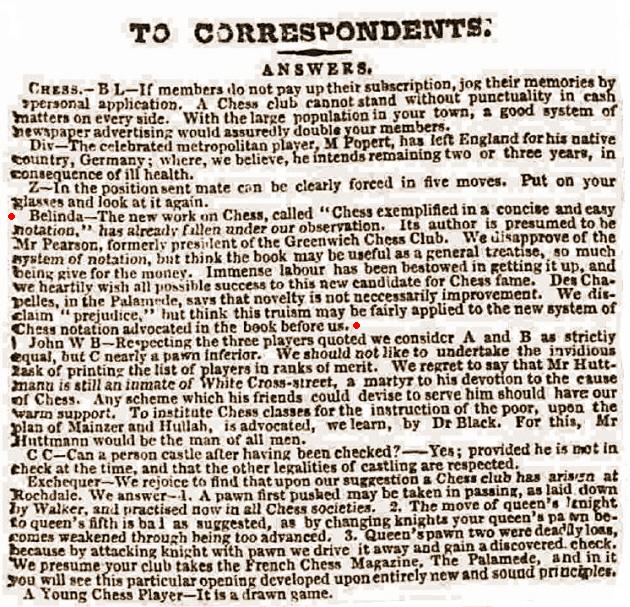

When the book was mentioned in Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 11 September 1842, page 2, Pearson, a former President of the Greenwich Chess Club, was named as the presumed author:’

8851. Guinness World Records 2015

The 2015 edition of Guinness World Records has slightly more chess material than usual. Under the heading ‘Chess master’ in the ‘Oldest people’ section, page 77 mentions Zoltan Sarosy, who ‘continues to play at 107 years of age’. Page 110 (‘Indoor pursuits’) has little items not only on the ‘Largest plastic-cup pyramid in 30 minutes’ but also on the ‘Fastest time to arrange a chess set’, ‘Longest chess marathon’, ‘Most chess games played in one location’ and ‘Largest chess set’. Kasparov’s defeat by Deep Blue in 1997 is mentioned on a page (204) which is entitled ‘Robots & Al’ and has the heading ‘In the Middle East, robot jockeys are replacing children in camel racing’.

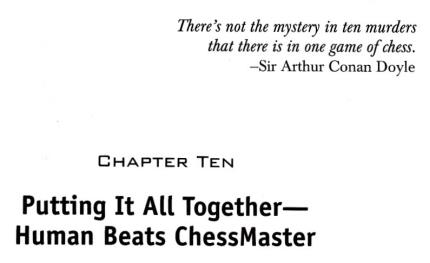

8852. The mystery in ten murders

Some chess books try to fabricate an air of cultivation by inserting quotes, however irrelevant, in chapter headings. From page 114 of Playing Computer Chess by Al Lawrence and Lev Alburt (New York, 1998):

The quote has nothing to do with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle but comes from the short story The Two Bottles of Relish by Lord Dunsany, as mentioned in our feature article on him.

From page 467 of the anthology 101 Years’ Entertainment The Great Detective Stories 1841-1941 edited by Ellery Queen (New York, 1941):

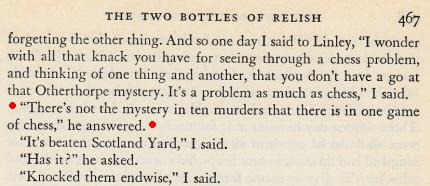

8853. A tribute by Lord Dunsany to T.R. Dawson

A poem on page 119 of CHESS, March 1952:

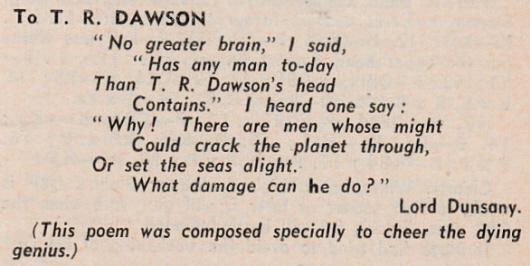

8854. Immortal games

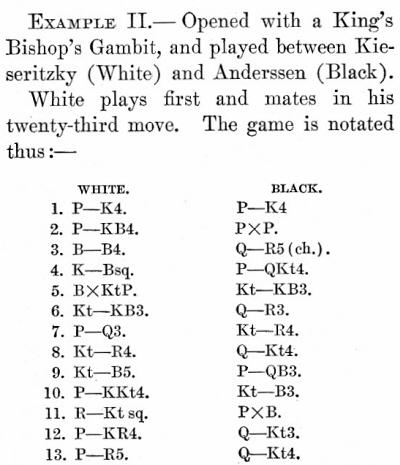

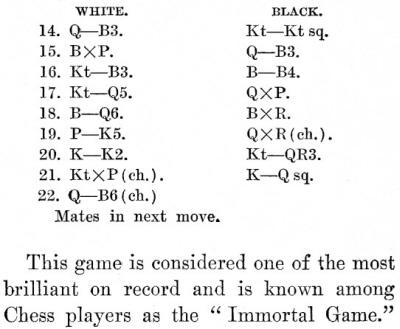

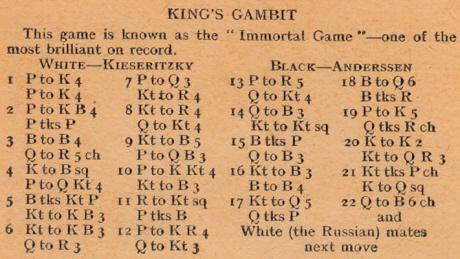

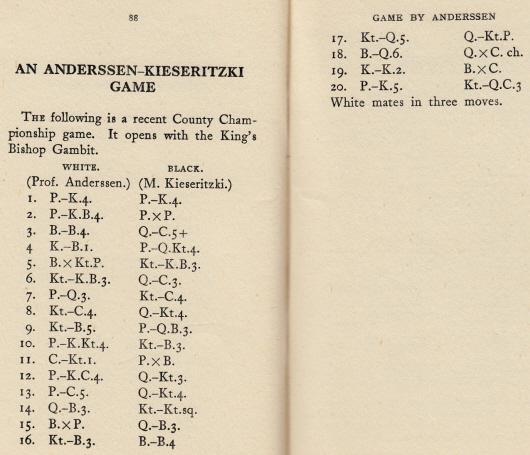

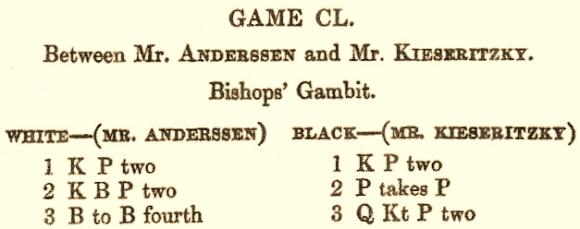

It has been shown that the ‘immortal games’ won by Nimzowitsch and Najdorf were not widely published at first. The same applies to the Immortal Game between Anderssen and Kieseritzky, although the loser did give it, with praise for Anderssen, on pages 221-222 of La Régence, July 1851.

Can readers help us to draw up a list of the game’s appearances in print in the mid-nineteenth century?

As mentioned in C.N. 2469, some books have inexplicably stated that Kieseritzky won. Below are the three cases referred to on page 314 of A Chess Omnibus:

Chess by R.F. Green (various editions)

Pages 155-156 of How to Play Chess by Charlotte Boardman Rogers (New York, 1907)

Page 45 of Chess & Draughts by Albert Belasco (various editions).

C.N. 1965 (see page 270 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) noted that the 1930s book Chess and How to Play It by B. Scriven correctly identified Anderssen as the winner but made a peculiar claim about the occasion of the game:

8855. Indian openings

A start has been made on adding citations and related information to Indian Openings in Chess.

Stephen Davies (Kallista, Australia) has sent us an annotation by Steinitz after 1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 Nf3 g6 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 Bg7 6 Be3 d6 in the fifth game of the 1892 US championship match between Showalter and Lipschütz:

‘The position resembles now one arriving from the Indian opening, which is greatly favored by Brahmin experts.’

Source: New-York Daily Tribune, 30 April 1892, page 5.

Our correspondent is currently completing work on a book about Lipschütz, scheduled for publication by McFarland & Company, Inc. in 2015.

8856. New books received

Two large books just received are The Classical Era of Modern Chess by Peter J. Monté (Jefferson, 2014) and Indian Chess History 570 AD-2010 AD by Manuel Aaron and Vijay D. Pandit (Chennai, 2014).

8857. Double sourcelessness

Ten chapters in the book mentioned in C.N. 8852, Playing Computer Chess by Al Lawrence and Lev Alburt (New York, 1998), start with a chess-related quote. All appear without the slightest source.

Eight of the ten can be found in Chess Quotations from the Masters by H. Hunvald (Mount Vernon, 1972). All appear without the slightest source.

8858. Rook and pawn ending

Black to move

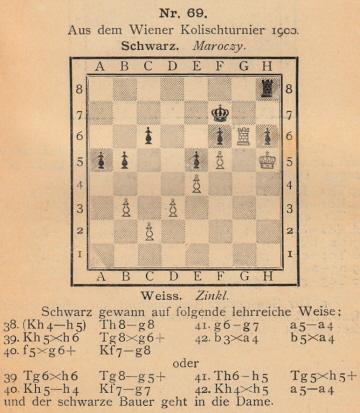

Should Black play 39...Rxg6+ and then create a passed pawn on the queen’s side? It has been suggested that this is what Géza Maróczy did in a game against Adolf Zinkl, thereby overlooking a mate in one in the diagrammed position.

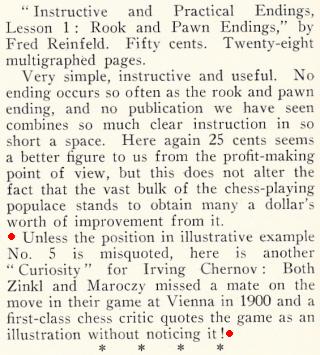

From page 366 of CHESS, 14 June 1937:

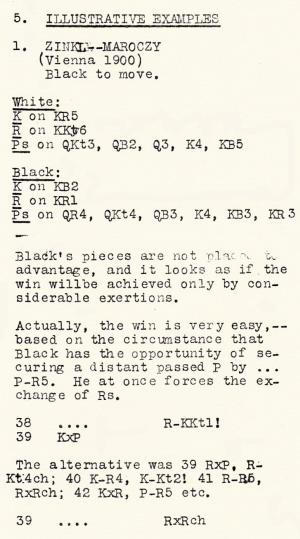

Below is the relevant part of pages 5-6 of Reinfeld’s Instructive and Practical Endings from Master Chess. Lesson I: Rook and Pawn Endings (New York, 1937):

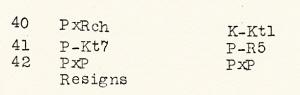

Our copy has an erratum slip:

The conclusion of the game was given on page 67 of L. Bachmann’s Schachmentor (Ansbach, 1904):

In reality, Zinkl v Maróczy (played in December 1899 in the Second Kolisch Memorial Tournament in Vienna, 1899-1900) ended 38 Kh5 Rg8 39 White resigns. The full game: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 d3 Nf6 5 Be3 Bxe3 6 fxe3 d6 7 Nc3 Na5 8 Bb3 O-O 9 Qe2 Nxb3 10 axb3 c6 11 O-O Ng4 12 h3 Nh6 13 g4 f6 14 Qg2 Nf7 15 Kh2 d5 16 Rg1 g6 17 Raf1 Be6 18 Qf2 Kg7 19 Rg3 h6 20 h4 dxe4 21 Nxe4 Bd5 22 Nfd2 Bxe4 23 Nxe4 Nd6 24 Nxd6 Qxd6 25 e4 Qd4 26 Qf3 Qxb2 27 Rf2 Qd4 28 h5 Qd7 29 hxg6 Qe8 30 Qf5 Qxg6 31 Rg1 Qxf5 32 gxf5+ Kf7 33 Rfg2 Rg8 34 Rg6 Rxg6 35 Rxg6 Rh8 36 Kh3 a5 37 Kh4 b5 38 Kh5

38...Rg8 39 White resigns.

Sources: pages 110-111 of the April 1900 Deutsche Schachzeitung and, as shown below, page 187 of Igy kezdtem ... by G. Maróczy (Budapest, 1942):

Thus Maróczy committed no oversight. The hypothetical mate in one (39 Kxh6 Rh8) was missed by L. Hoffer when he annotated the game in the 13 January 1900 issue of The Field. After 38...Rg8 he wrote:

‘A very pretty move. If 39 K takes P, then 39...R takes R ch wins ...’

Hoffer’s notes were reproduced on pages 37-38 of Vienna 1899/1900 edited by A.J. Gillam (Nottingham, 2008) without mention of the missed mate in one.

8859. The value of pieces

Concerning the value of the chess pieces, Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) writes:

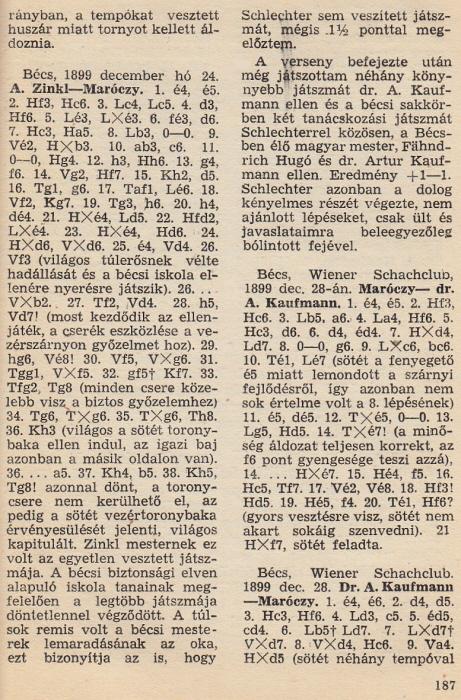

‘Lasker’s Chess Magazine published a series of copyrighted articles by Emanuel Lasker on basic chess instruction, and on pages 188-189 of the August 1905 issue he discussed the value of pieces. After describing the methods of Jaenisch and the mathematician Euler, he gave, on page 189, a peculiar scale:

“The values of the pieces calculated with sufficient accuracy for over the board play are as follows:

Pawn, 6; knight, 17; bishop, 17; rook, 24; queen, 47.

These values have not been found by executing the indicated calculation, but are those which come nearest to express my experience in hard fought games.”

Lasker then added some provisos and concluded by giving the king a value of 20.

I have yet to find any occurrence of these values elsewhere in Lasker’s writings.’

8860. Alekhine’s Gun (C.N.s 7880, 7914, 7972 & 8625)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) sends a game from page B5 of the New-Yorker Staats-Zeitung, 28 January 1923:

Edmund Farago – Jacob Bernstein

New York, January 1923 (Rice Progressive Chess Club

Championship 1922-23)

Old Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 d6 3 Nc3 Bf5 4 e3 Nbd7 5 Bd3 Bg6 6 Bxg6 hxg6 7 Nf3 e5 8 b3 c6 9 Bb2 Qc7 10 Qd3 Be7 11 h3 O-O 12 O-O Rfe8 13 Nd2 Nh7 14 f4 f5 15 Kh1 e4 16 Qe2 Nhf6 17 g4 Kf7 18 g5 Nh7 19 Kg2 Rh8 20 Rh1 Nhf8 21 Nf1 Ne6 22 Ng3 Rh4 23 Qd2 Rah8 24 Nce2 d5 25 Rac1 Qd8 26 c5

26...R8h7 27 Bc3 Qh8 28 Ng1 Bxg5 29 fxg5 Nxg5 30 Kf1 Nf6 31 Qf2 Nxh3 32 Nxh3 Rxh3 33 Rxh3 Rxh3 34 Rc2 Qh4 35 Be1 Ng4 36 Qf4 Nh2+ 37 Ke2 Qxf4 38 exf4 Nf3 39 Bf2 Kf6 40 Rc1 g5 41 fxg5+ Kxg5 42 Rd1 f4 43 Nxe4+ dxe4 44 d5 cxd5 45 Rxd5+ Kg4 46 Rd7 Ne5 47 Rxg7+ Kf5 48 Rxb7 Rh2 49 c6 e3 50 c7 Rxf2+ 51 Kd1 Rd2+ 52 Kc1 Nd3+ 53 Kb1 Rb2+ 54 Ka1 Rc2 53 White resigns.

8861. Chess Exemplified (C.N.s 8845 & 8850)

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) notes that Pearson was mentioned, without a forename, in the bibliographical catalogue on page 362 of The Art of Chess-Play by George Walker (London, 1846):

8862. The Immortal Game (C.N. 8854)

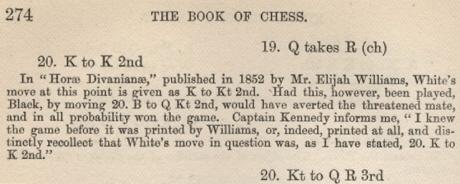

Mr Clapham also mentions that the Immortal Game was published on pages 171-172 of Horæ Divanianæ by Elijah Williams (London, 1852):

Our correspondent furthermore points out a remark on page 274 of The Game of Chess by George Selkirk (London, 1868):

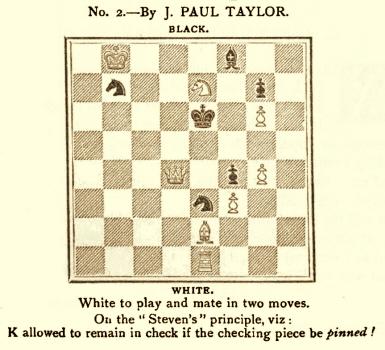

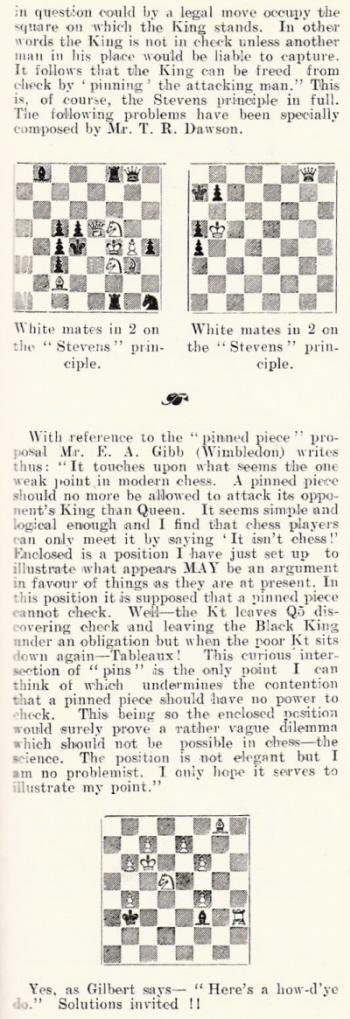

8863. The Stevens principle

Mate in two.

The solution is 1 Kc7, and if 1...Nd5+ 2 Bc4 mate. This problem, by J. Paul Taylor, was given in the ‘Puzzles’ section of his book Chess Chips (London, 1878). The solution at the end of the work (another unnumbered page) was ‘Kt to B7’, a typographical error pointed out by W.N. Potter on page 165 of the March 1879 Huddersfield College Magazine. On page 163 Potter described the composition as ...

‘... a two mover of Mr Taylor’s upon the Stevens’s principle, and it is no doubt an apt illustration of that most eccentric and unreasonable of deviations from the beaten track of chess’.

The problem as it appeared in Chess Chips:

The ‘principle’ was advocated in a letter, ‘Metamorphose. A Novelty in Chess’, which S.J. Stevens of the City of London Chess Club contributed on pages 121-122 of the 1 November 1875 issue of the Westminster Papers. It was illustrated by this position:

Stevens commented:

‘The king is now in check and, by the old code, must move, but by the new rule, as suggested, White can cover by queen to QB4, because the knight could not capture without discovering check upon his own king. If following this move B checks at B4, queen cannot capture, as it would leave the king in check. If B checks at B5, the queen cannot capture for the same reason, but the king can then take, as his condition is relatively the same; and lastly, if Black, instead of moving his B on the second move, play K to any square but B2, the conditions are altered, the white king is really in check, and the king must move or the knight be taken.’

The letter from Stevens gave a lengthy explanation of his proposal (‘an antidote ... to the universal bane of bookishness’). A further extract:

‘For reasons, perhaps only too obvious, there is, on the part of players possessing, in a large degree, the faculty of originality combined with ingenuity, a disrelish to compete with players who have digested, if not swallowed, the standard tomes of the great masters, and satiated their minds with the masterpieces of every finished executant from Philidor to Morphy. Undoubtedly most, if not all, of the many attempts to afford a more extended scope for original variety have been set on foot with a desire to counteract what is regarded as the worst features of the cramming system. A mental joust at chess should be each combatant deploying his own forces, unaided by supplementary assistance.’

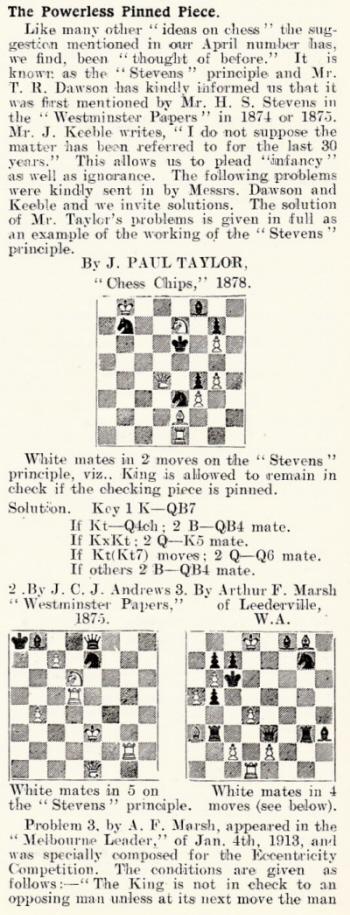

Only the problem world seems to have taken any interest in the Stevens ‘principle’, although it was not widely known. Below is an item on pages 208-209 of the April 1913 Chess Amateur, in H. Meek’s ‘Half-Hours’ column:

‘The Powerless Pinned Piece

Many suggestions appear from time to time, spring-time not excepted, for varying the “game and playe of the chesse”. Problem composers, especially, are grumbling because they have, seemingly, exhausted all orthodox methods of construction. We do not think the following suggestion has ever before been made: When a piece or pawn is “pinned” to its king, the said piece or pawn shall be entirely powerless. The chief innovation would be to allow the opposing king to move to squares which, under present rules, are “governed” by the “pinned” man. The sudden release of a “pinned” piece when the opposing king stands on a “governed” square should introduce novel and exciting complications. Would any composer care to send up an illustrative problem?’

This prompted a feature, with Stevens’ name recalled inaccurately, on pages 272-273 of the June 1913 Chess Amateur:

Can a brief biographical note on Samuel John Stevens be drawn up? Page 337 of the September 1928 BCM reported that he had ‘died recently in his 80th year’.

| First column | << previous | Archives [122] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.