Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [123] | next >> | Current column |

8864. Stephen Fry

The latest book by Stephen Fry, More Fool Me (London, 2014), has many passages about chess in the chapter featuring his 1993 diary. They relate to that year’s Kasparov v Short match and begin on page 262.

8865. S.J. Stevens (C.N. 8863)

William D. Rubinstein (Melbourne, Australia) writes:

‘Samuel John Stevens of 72 Osbaldeston Road, Stoke Newington, Middlesex died on 7 July 1928, leaving £6,197. His executor was his widow, Mary Jane Stevens. His birth was registered in the St Luke district of the City of London in the October-December quarter of 1847. In the 1901 Census he was described as a “retired engraver”, and the 1911 Census stated “Private Means”. The source of this information is the website ancestry.co.uk.’

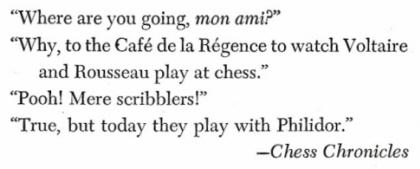

8866. Voltaire, Rousseau and Philidor

Trustworthy writers naturally resist the temptation to repeat unverified material, and especially in a domain such as chess lore which is notoriously infested with imprecision and uncertainty.

From page 220 of Total Chess by David Spanier (London, 1984):

‘I can’t resist repeating that old anecdote about the man going into the café [the Café de la Régence] to watch Voltaire and Rousseau play at chess. Mere scribblers, those two, sniffs an acquaintance. “True, but today they play with Philidor!”’

Information is sought about the tale, which had appeared on page 92 of The World of Chess by A. Saidy and N. Lessing (New York, 1974):

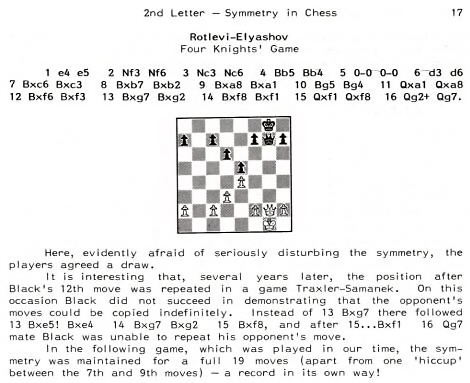

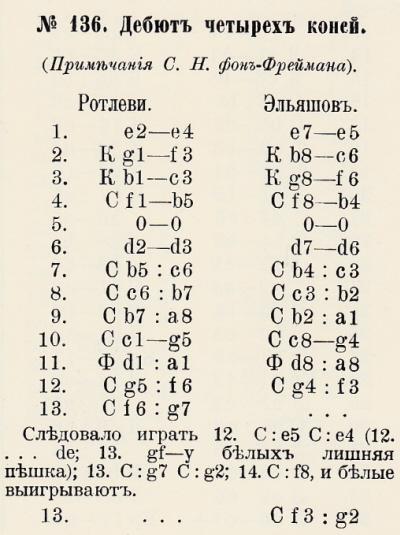

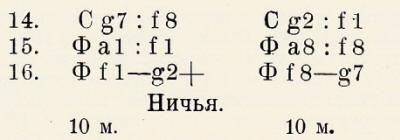

8867. Symmetry

With regard to the short game Rotlewi v Eljaschoff (Elyashov), St Petersburg, 1909, Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) wonders whether the fact that neither 13 Bxe5 nor 14 Qc1 was played suggests that it was a pre-arranged draw.

The game was referred to, in the context of symmetry, in C.N.s 1488 and 1507 (see page 258 of Chess Explorations). The former item mentioned page 17 of Chess Kaleidoscope by A. Karpov and Y. Gik (Oxford, 1981):

The book’s only other information about the game, on page 16, was that it was ‘played at the beginning of this century’.

In C.N. 1507 François Zutter (Founex, Switzerland) referred to the game’s publication on pages 353-354 of the Russian-language book on St Petersburg, 1909, which recorded that it was played in the last round of the All-Russian Hauptturnier on 27 February. The symmetry was not perfect (2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6), but the final clock-times were identical (ten minutes per player):

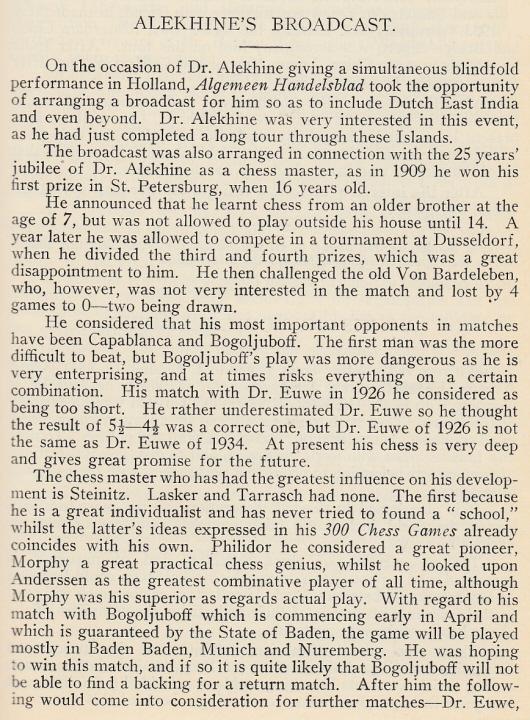

8868. A radio broadcast by Alekhine

From pages 97-98 of the March 1934 BCM:

A small correction was published on page 181 of the April 1934 issue:

Regarding the ‘unsystematic book The Soul of Chess (in German)’ referred to in the BCM report, on pages 5-6 of Alekhine Nazi Articles (Olomouc, 2002) K. Whyld speculated that, although no such book ever appeared, ‘perhaps some of the ideas that were in Alekhine’s mind at that time appeared in the PZ [Pariser Zeitung] series’.

8869. The soul of chess

Some additional quotes:

- ‘Position is the soul of chess.’

Source: Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 22 November 1835, page 3.

- ‘The pawns are more than the soul of chess; they are its alpha and omega; and most slightingly are the sturdy little urchins treated.’

Source: Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 21 May 1840, page 4.

- ‘Counter-attack is the vital spirit – the very soul of chess.’

Source: Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 24 December 1843, page 2.

- ‘Philidor styled the pawns the soul of chess; the epithet might better attach to the rooks when in support of each other.’

Source: Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 20 January 1872, page 2.

Wolfgang Heidenfeld’s entry on aphorisms on page 16 of The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977) included the following:

‘“Exchanging is the soul of chess” (Kieninger).’

No source was supplied, and the observation has also been given without further particulars in the entries on Georg Kieninger in a number of German chess encyclopaedias:

- ‘Von ihm stammt der kennzeichnende Ausspruch “Der Abtausch ist die Seele des Schachspiels”.’

Sources: Großes Schach Lexikon by Klaus Lindörfer (various editions as from 1977, page 138) and Das rororo Schachbuch von A-Z by Klaus Lindörfer (Hamburg, 1984), page 138.

- ‘Von dem “Eisernen Schorsch”, wie ihn seine vielen Freunde nannten, stammen manche kernige Aussprüche: “Der Abtausch ist die Seele des Schachspiels”. Dieser Satz charakterisiert ein wenig seine Auffassung vom Spiel.’

Source: Lexikon für Schach Freunde edited by Manfred van Fondern (Lucerne and Frankfurt/M., 1980), page 153.

- ‘Von K. stammt der Grundsatz “Der Abtausch ist die Seele des Schachspiels”.’

Source: Meyers Schach Lexikon edited by Otto Borik (Mannheim, Leipzig, Vienna and Zurich, 1993), page 150.

Our latest feature article, bringing together citations noted previously, is The Soul of Chess.

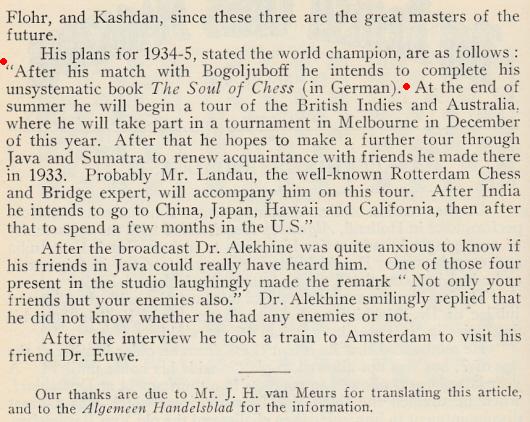

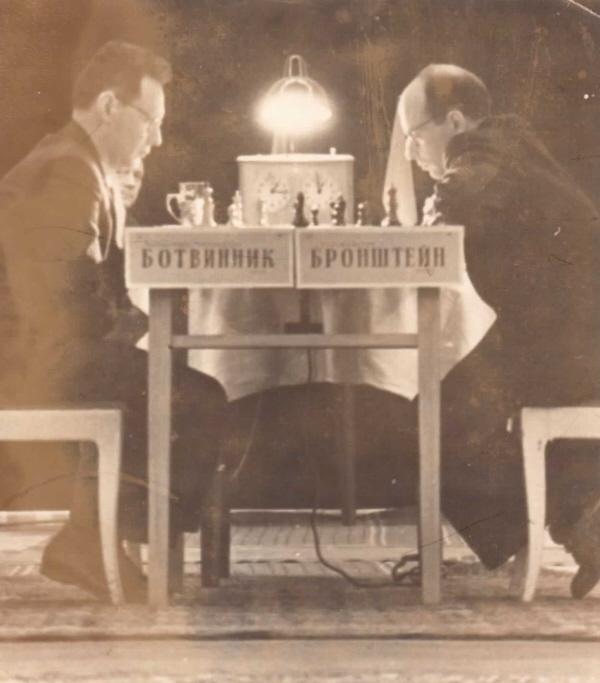

8870. Botvinnik v Bronstein

This photograph from the 1951 world championship in Moscow has been sent to us by Sergey Solodukhin (Saint-Branchs, France). He believes that it was taken by his father, Nicolai, in whose archives it was found.

8871.

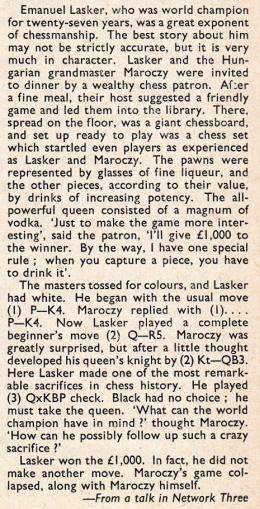

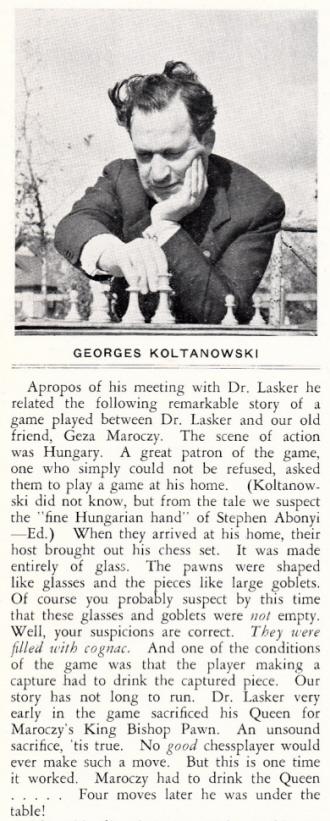

Quaffing cognac or vodka

C.N. 3196 (see A Chess Database) mentioned the moves 1 e4 e5 2 Qh5 Nc6 3 Qxf7+, and there are many versions of the related story involving Emanuel Lasker. One ‘is-said-to’ example comes from page 90 of A History of Chess by Jerzy Giżycki (London, 1972):

‘Lasker is said to have won a game of “Alcoholic Chess” by sacrificing his queen in ridiculous fashion at the very outset of the game. The queen contained about a quarter litre of cognac; quaffing this seriously incapacitated his opponent in the ensuing complications – B.H. Wood.’

Page 283 of the August 1959 CHESS had an account reproduced from a chess programme on BBC radio:

How far back can the story be traced? We recall an editorial account of a lunch with G. Koltanowski, one of the least reliable of all chess chroniclers, on page 255 of the November 1938 Chess Review:

8872. Instructions To Young Chess-Players

From the inside front cover of CHESS, 18 October 1958 we quote the opening sentence of a brief notice of Instructions To Young Chess-Players by H. Golombek (London, 1958):

‘A book with no special features, except that in his bibliography the author recommends fewer of his own books than usual.’

8873. A mass of contradictory information

‘X’ is an imaginary prolific chess author (‘book-doer’ may be a better term) who decides to bring out an anthology of miniature games won by the world chess champions. A day or two’s casual clicking in his database suffices for the requisite ‘research material’ to be assembled. The book is quickly completed and, no less quickly, warmly welcomed by the review-doers.

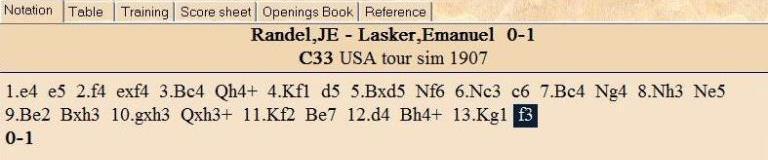

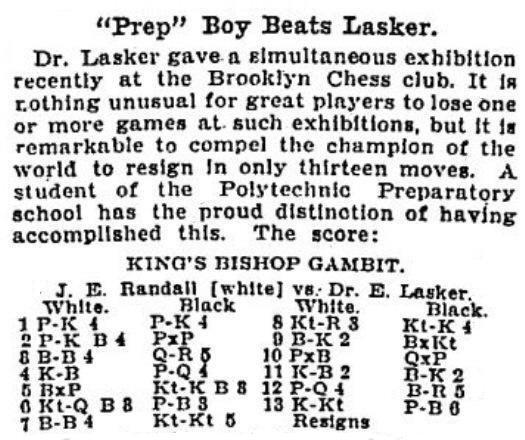

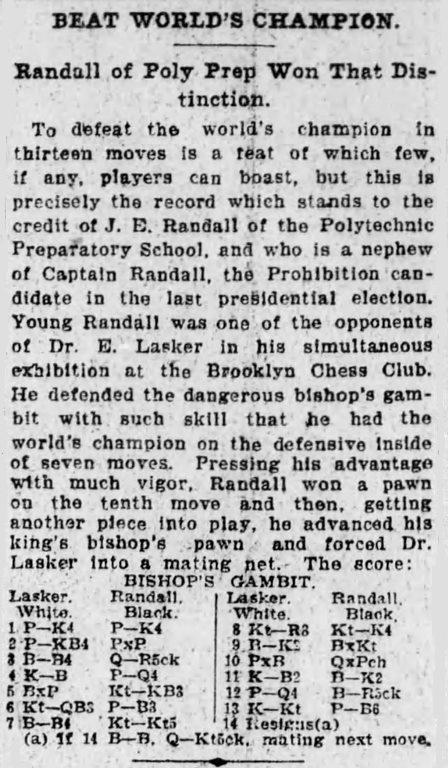

One of the games in the compendium is a 13-move victory by Emanuel Lasker against J.E. Randel, courtesy of (i.e. unquestioningly lifted from) Mega Database 2012:

At best, ‘X’ contributes to chess knowledge by mentioning that Black missed a mate in five at move 11.

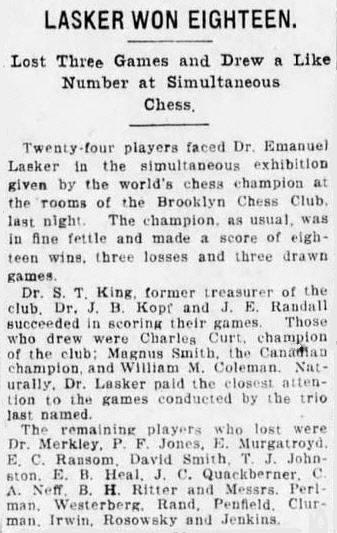

A more conscientious writer might wonder whether nothing more precise than ‘USA tour sim 1907’ is available, and whether the unusual spelling ‘Randel’ is correct. If FatBase 2000 is consulted, an exact place, New York, will be found, as well as an unwelcome complication: the loser was identified there as ‘J. Randall’.

‘X’ has long since exhausted his interest in the matter, but others may contemplate the drastic step of ascertaining what has appeared in print, whether in primary or secondary sources.

Page 61 of Emanuel Lasker Volume 3 by K. Whyld (Nottingham, 1976) named White as ‘J.E. Randall’, and two sources for the game were mentioned, without dates: the Chicago Sunday Tribune and the Chess Amateur.

Below is what was published on page 4 III (Sporting section) of the Chicago Sunday Tribune, 15 December 1907:

Something is clearly awry here, because the introductory text says that Lasker lost, whereas the game-score specifies that he won.

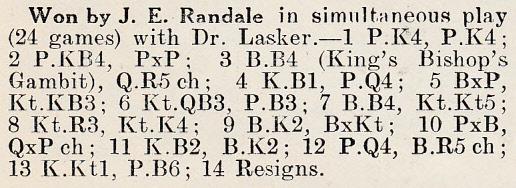

The Chess Amateur also has a surprise to offer. The Lasker game was one of eight bunched together, with scant information, in the ‘Brilliants and Miniatures’ column on page 271 of the June 1908 issue:

So now there is not only another name, ‘J.E. Randale’, but also the statement that he won the game.

The researcher hopeful of discovering the game-score in the American Chess Bulletin will be disappointed, although a vague passage by Thomas J. Johnston may be found hidden away on page 251 of the December 1908 issue:

‘When the world’s champion gave his simultaneous exhibition in Brooklyn, last year, in which the writer’s Caissic scalp hung at his belt with some 20 others, he offered a King’s Gambit to a young student, not a strong player, who defended conventionally with the counter-attack Q-R5ch. At the tenth move or thereabouts, Black advanced a pawn one square, whereupon the champion resigned.’

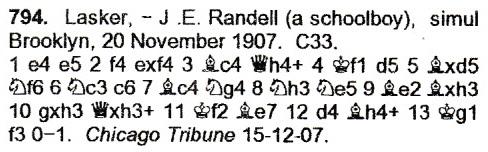

Next, it is necessary to consider page 127 of K. Whyld’s second anthology on the world champion, The Collected Games of Emanuel Lasker (Nottingham, 1998):

This time it is said that Lasker was White, and Black’s name has become yet another variant, ‘J.E. Randell’.

Fortunately, the whole affair is not as intractable as it may seem. The obvious source to consult for a game played in Brooklyn is the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. That newspaper’s chess coverage systematically used the spelling ‘J.E. Randall’, and not least when reporting his victory over Lasker the day after the simultaneous exhibition (on page 18 of the 21 November 1907 edition):

‘J.E. Randall’ was also the spelling when the game-score was published on 8 December 1907 (page 10):

By now, the historian will hardly have grounds for doubting that in Brooklyn on 20 November 1907 Emanuel Lasker lost to J.E. Randall. Although remaining on the look-out for further information, he may find his attention switching to the references in the above Eagle cutting to J.E. Randall and his uncle, Captain Randall, in the hope that some biographical data can be traced.

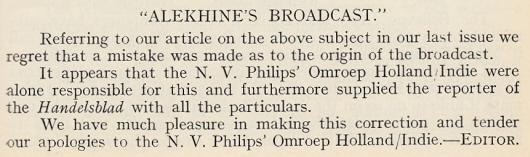

8874. The Neo-Sveshnikov

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) notes the title page of The Neo-Sveshnikov by Jeremy Silman (Moon Township, 1991):

8875. Black

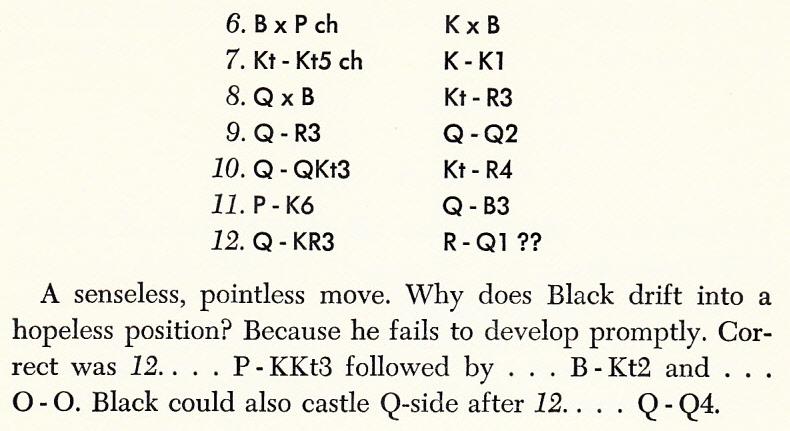

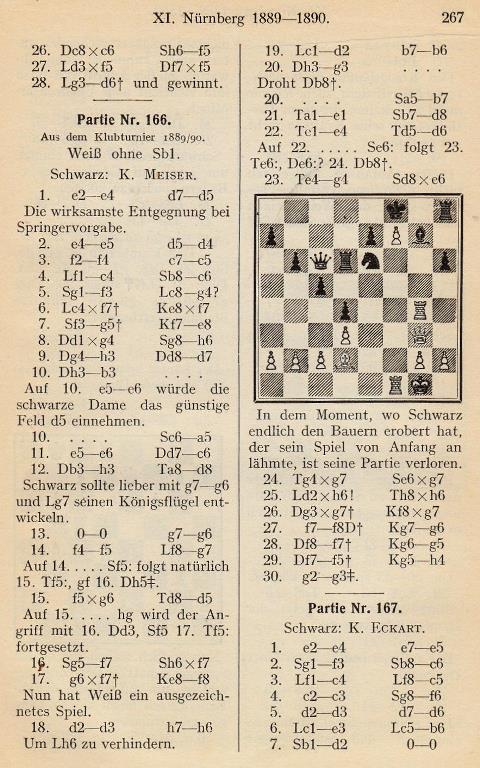

to move

Black to move.

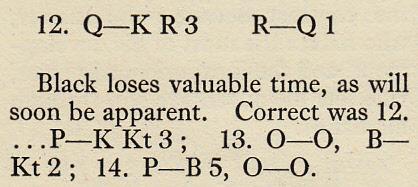

Black now played 12...Rd8, but instead should he have attempted to consolidate his position with 12...g6, 13...Bg7 and 14...O-O, or, alternatively, with 12...Qd5, followed by queen’s-side castling?

Reuben Fine recommended those ‘correct’ lines on page 188 of The Middle Game in Chess (New York, 1952) when annotating the game Tarrasch v Meiser:

The game was included in Tarrasch’s Dreihundert Schachpartien. Below, for instance, is page 267 of the third edition (Gouda, 1925):

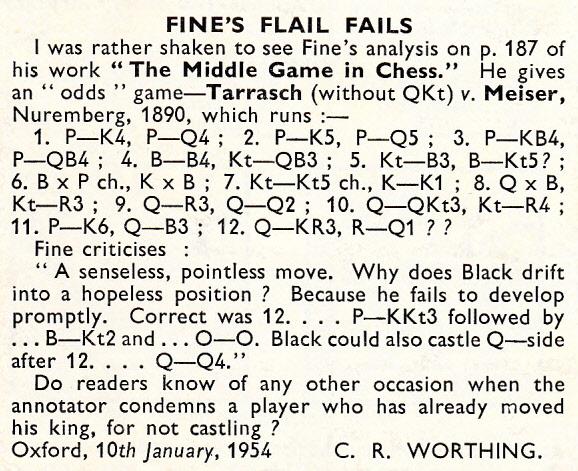

The earliest correction of Fine’s note that we can cite was by C.R. Worthing of Oxford in a letter dated 10 January 1954 on page 98 of the March 1954 CHESS:

The oversight in The Middle Game in Chess was also pointed out by H. Vaughan of Chatswood, Sydney on page 133 of Chess World, July 1960.

8876. Peak age

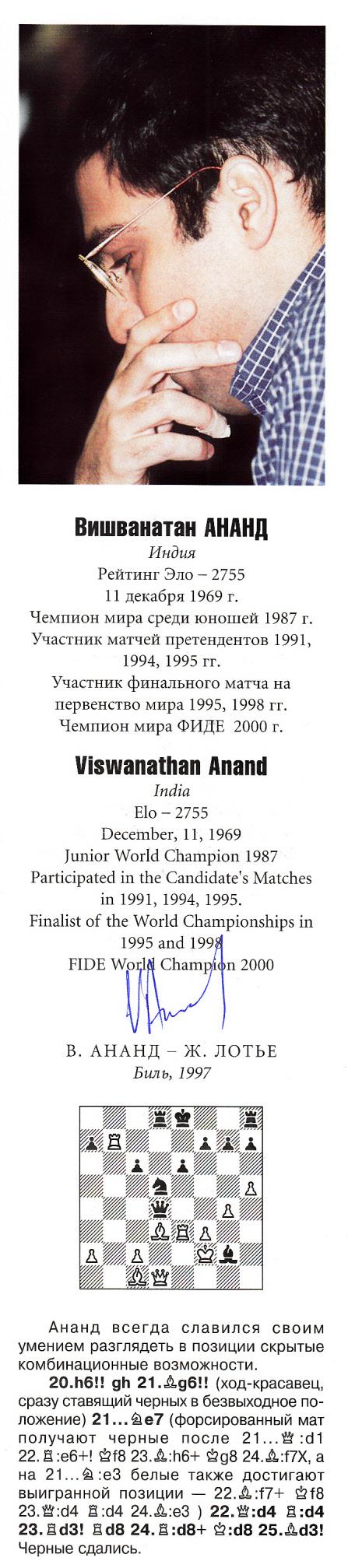

From page 20 of the programme for the 2002 ‘Russia versus the World’ event in Moscow:

The November 2014 world championship match between Carlsen and Anand will be taking place one month before the latter’s 45th birthday.

C.N. 1288 (see page 127 of Chess Explorations) quoted from page xvii of My Best Games of Chess 1905-1930 by S.G. Tartakower (London, 1953):

‘If one wishes to generalize one might say that as a rule it is towards his 45th year that an intellectual worker is most successful. In my own case it was not till 1930 that at long last I achieved a first prize in a big international tournament in which several great masters competed (at Liège).’

We add now that the same age was specified by Euwe in a Dutch newspaper (can a precise source be found?) quoted on pages 325-326 of the July 1961 CHESS in the context of that year’s return match between Tal and Botvinnik:

‘Writing in a Dutch newspaper before the match, Euwe pointed out that recent tournament results in general had confirmed that the rewards in modern chess go to the younger men.

“Chess masters reach their peak about the age of 45. Alekhine won back the world championship at this age. Capablanca celebrated his 45th year with his success at Moscow and Nottingham, 1936. Lasker was 45 when he won the tournament of St Petersburg, 1914. I myself finished second to Botvinnik at Groningen in 1946, ahead of Smyslov, Szabó, Najdorf and others.

After 45, you begin to go back. Botvinnik lacked his usual certainty in his matches with Smyslov in 1957 and 1958. Capablanca, then 49, failed in the AVRO tournament, 1938 – as I did in the 1948 world championship match-tournament.

Lasker, yes, he was the exception: he won the strong New York tournament of 1924 ahead of Alekhine and Capablanca. The question now is, will Botvinnik prove to be another Lasker or will he follow the general trend?”’

Arpad Elo’s views on age were quoted in C.N. 1330, an item reproduced on page 127 of Chess Explorations. He considered that ‘peak performance is attained around age 36’.

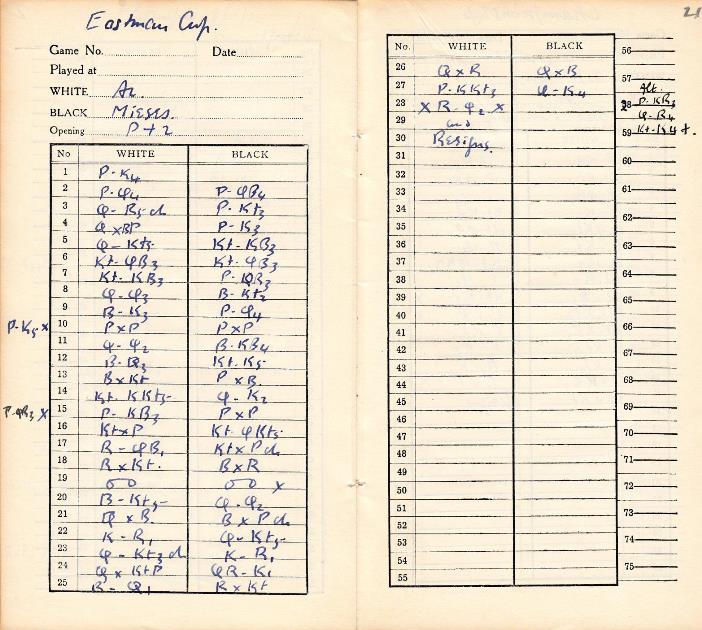

8877. Laing v Mieses

This is a further game from the score-books of A.G. Laing (C.N.s 8728 and 8762), and a late specimen of play at the odds of pawn and two moves. The only information about the occasion is ‘Eastman Cup’, but the chronological order suggests that the game was played in or around October 1941.

A.G. Laing – Jacques Mieses

Eastman Cup, London (1941?)

(Remove Black’s f-pawn.)

1 e4 … 2 d4 c5 3 Qh5+ g6 4 Qxc5 e6 5 Qb5 Nf6 6 Nc3 Nc6 7 Nf3 a6 8 Qd3 Bg7 9 Be3 d5 10 exd5 exd5 11 Qd2 Bf5 12 Bd3 Ne4 13 Bxe4 dxe4 14 Ng5 Qe7 15 f3 exf3 16 Nxf3

16...Nb4 17 Rc1 Nxc2+ 18 Rxc2 Bxc2 19 O-O O-O 20 Bg5 Qd7 21 Qxc2 Bxd4+ 22 Kh1 Qg4 23 Qb3+ Kh8 24 Qxb7 Rae8 25 Rd1 Rxf3 26 Qxf3 Qxg5 27 g3 Qe5 28 Rd2 and White resigns.

8878. Tarrasch v Meiser (C.N. 8875)

Pete Klimek (Berkeley, CA, USA) notes that illegal castling was also proposed in the note to the Tarrasch v Meiser game on page 306 of Tarrasch’s Best Games of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (London, 1947):

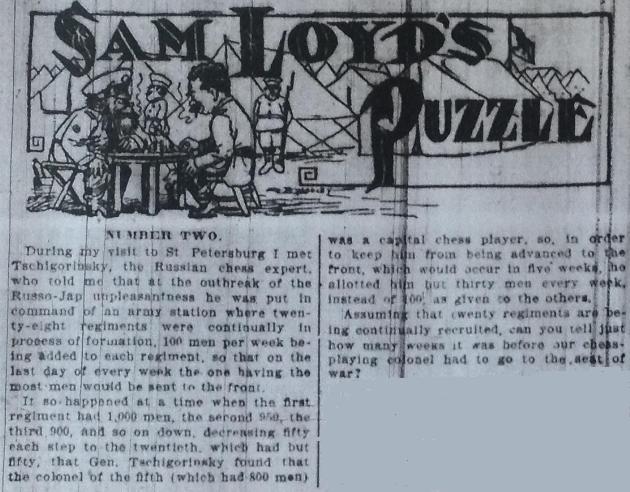

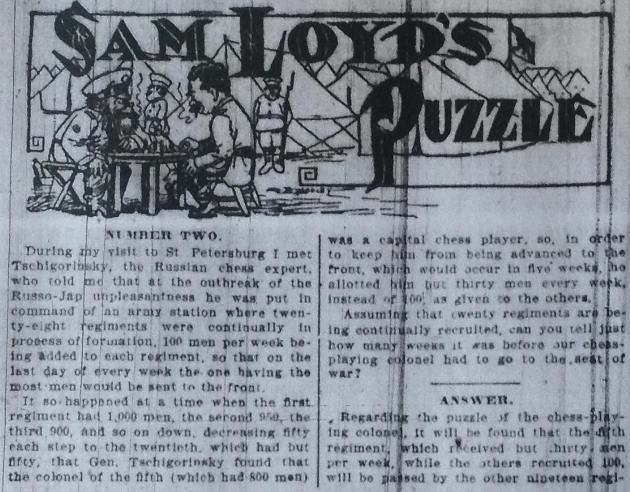

8879. Tschigorinsky

Eduardo Ramirez (Chicago, IL, USA) has found this puzzle

by Sam Loyd in the Chicago Daily News, 22 November

1905:

For now, the remainder of the item (the solution) is omitted.

The puzzle was reproduced, under the title ‘The Chess Playing Colonel’, on page 27 of Mathematical Puzzles of Sam Loyd selected and edited by Martin Gardner (New York, 1959). The solution was on page 131.

8880. A one-stringed fiddle

Some comments about Max Euwe by W.A. Fairhurst on page 11 of the October 1928 Chess Amateur:

‘The advancement during the last few years of Max Euwe, the young Dutch master, has been of considerable interest. Despite very few appearances in master tournaments he has risen steadily in rank until he can now be classed as one of the six strongest masters of the world. His recent opening play has, however, been very indifferent, and it may almost be said that he plays a one-stringed fiddle, the King’s fianchetto. It may confidently be asserted that until he abandons the illogical attitude that the King’s fianchetto is the only method of attack, as well as defend, he will advance no further, and more probably suffer in decline. A player with one idea is after all of little interest to the major portion of chess lovers, and the writer is frankly disappointed with the games of the Dutch expert. Let us hope that he will change his opening methods, before the lack of variety has the effect of dulling his undoubted natural talent.’

This was Fairhurst’s first note, after 1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 c5 3 g3, in the game Euwe v Capablanca, Bad Kissingen, 1928 (a 43-move draw).

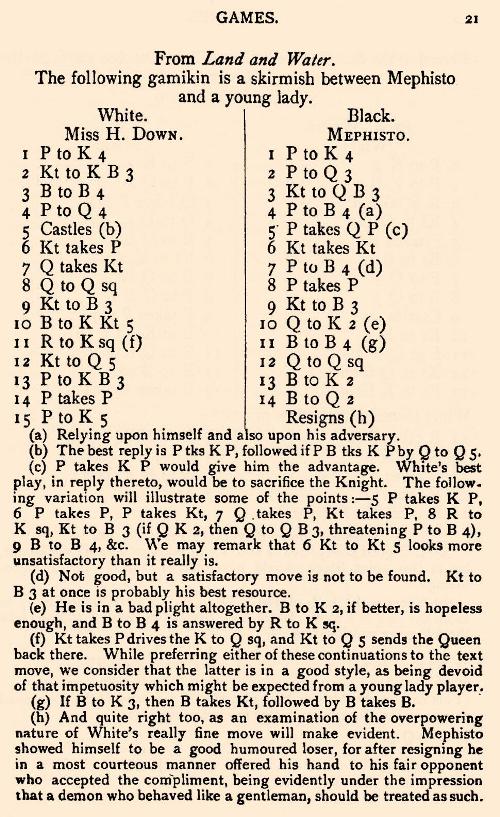

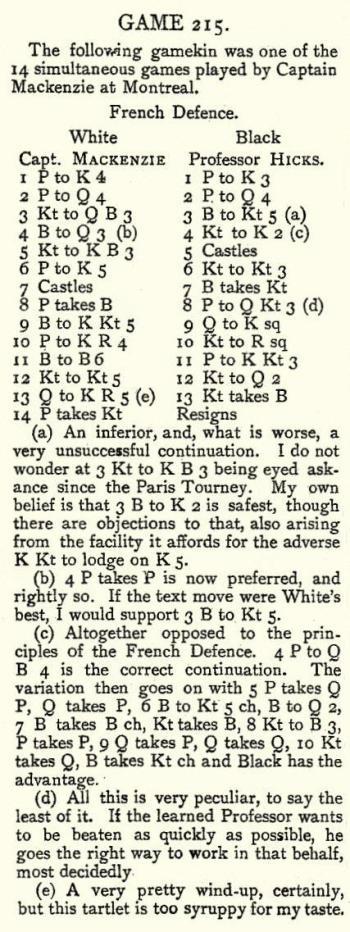

8881. The following gamikin and gamekin

Two games introduced with unusual words:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 Bc4 Nc6 4 d4 f5 5 O-O exd4 6 Nxd4 Nxd4 7 Qxd4 c5 8 Qd1 fxe4 9 Nc3 Nf6 10 Bg5 Qe7 11 Re1 Bf5 12 Nd5 Qd8 13 f3 Be7 14 fxe4 Bd7 15 e5 Resigns.

Source: page 21 of Chess Chips by J. Paul Taylor (London, 1878).

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Bd3 Ne7 5 Nf3 O-O 6 e5 Ng6 7 O-O Bxc3 8 bxc3 b6 9 Bg5 Qe8 10 h4 Nh8 11 Bf6 g6 12 Ng5 Nd7 13 Qh5 Nxf6 14 exf6 Resigns.

Source: the annotated games column by W.N. Potter on page 239 of the Westminster Papers, 1 March 1879.

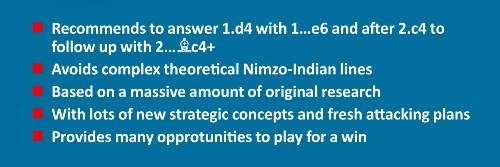

8882. New in Chess

Peter Verschueren (Kudelstraat, the Netherlands) notes an advertisement for The Modern Bogo 1 d4 e6 by Dejan Antic and Branimir Maksimovic (Alkmaar, 2014) on page 107 of the 6/2014 New in Chess. ‘A complete & fresh repertoire against 1 d4’ is proposed, by means of 1...e6 2 c4 Bc4+.

‘Recommends to answer’ is, in any case, strange, and the final line has ‘opprotunities’.

8883. Players and spectators

Wanted: information about a matter briefly reported on page 254 of CHESS, 16 June 1956:

‘Spectators’ advice to players in a simultaneous display is a terrible tradition. We have never seen this put quite so wittily as in a report of a recent display by Sammy Reshevsky in the Central YMCA of Columbus, Ohio:

“Of the 35 players and 46 ‘spectators’, only two got draws.”’

8884. Ernest Kim

From page 18 of A Book of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1973):

‘Fifteen to 20 years ago I published an account of a Korean [sic] boy, Ernest Kim; this drew a letter in which the writer said that, travelling along the “Golden Road to Samarkand”, he had stopped overnight at Tashkent. He admitted to playing a little chess and was at once pressed by the locals to play “our champion”; he reluctantly agreed – and a tiny four-year-old was brought in. It was Kim. But now he must be about 20 – and I have never seen his name as an adult player.’

From Alexander’s writings we can quote only two other brief references to Kim:

‘A new chess prodigy has appeared who makes Bobby Fischer appear senile. Ernest Kim has won the championship of Tashkent at the age of five; however, he is not yet of master strength – only about average British championship standard.’

Source: Sunday Times, magazine section, 15 February 1959, page 26.

Secondly, ‘Ernest Kim, the five-year-old champion of Tashkent’ was referred to by Alexander on page 28 of the Sunday Times, magazine section, 5 April 1959.

Kim had been mentioned on page 106 of CHESS, February 1959 (‘issued 28 January 1959’):

‘Bobby Fischer overtrumped?

Chess prodigies are getting younger.

The latest makes 15-year-old Bobby Fischer of Brooklyn, who has again won the US championship, an utter greybeard.

He is Ernest Kim, who, at the age of five, has beaten everybody else in his home town of Tashkent, Central Asia. And they play good chess in Central Asia these days!’

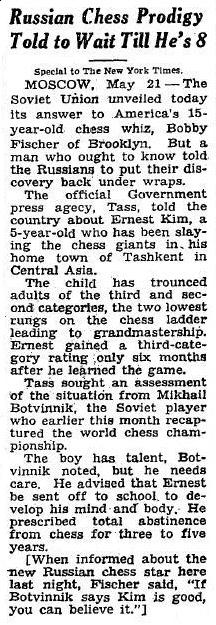

As shown below, page 40 of the New York Times, 22 May 1958 had reported a statement by Botvinnik that Kim had talent, followed by a comment from Fischer: ‘If Botvinnik says Kim is good, you can believe it.’

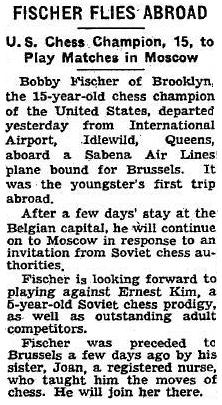

The following month, on page 46 of the 18 June 1958 edition of the New York Times, it was stated that ‘Fischer is looking forward to playing against Ernest Kim, a 5-year-old Soviet chess prodigy’:

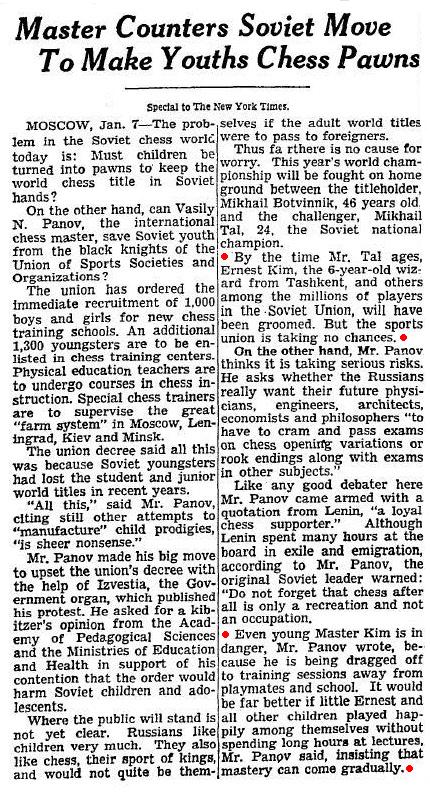

What, if anything, happened thereafter is currently unclear, but Kim’s name did appear again on page 9 of the New York Times, 8 January 1960, in a discussion on the Soviet Union’s handling of chess prodigies:

Regarding Panov and Kim, see too the article ‘USSR Youth Program in Chess’ on page 33 of the February 1960 Chess Review.

A fine photograph of Kim is available online, as is some Pathé footage, from which a still is shown here:

One or two databases contain a draw between Alexander Kotov and Ernest Kim. It was supposedly played in Tashkent in 1953, even though that is the approximate year of Kim’s birth. A final mystery for now is that the FIDE website has a ‘profile’ for a player named Ernest Kim (Russia) whose year of birth is given as 1945.

What more can be discovered about the prodigy, and especially in Russian-language sources?

8885. The value of the pieces

Concerning the value of the chess pieces, Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) refers to an 1857 edition of Hoyle’s Games by Thomas Frère:

‘Frère was a significant chess author, so this edition is more accurate on chess than other works bearing the “Hoyle’s” name. Moreover, Frère’s Preface, dated March 1857, makes it clear that the book is original and unrelated to Hoyle’s traditional works. It states (page iii):

“There isn’t a line of ‘Hoyle’ in it. Hoyle is a fossil, and suited only to fossil players.”

Although my copy is dated 1875, it seems to be an essentially unaltered reprint of the 1857 edition. All the chess content appears consistent with early 1857.

On page 235 Frère writes:

“Relative value of the pieces. The relative value of the pieces is estimated as follows: the queen is worth, say, 10 pawns; the rook 5; the bishop 3½; the knight 3½.”

This is the earliest publication that I have seen which gives the bishop and knight the same value.’

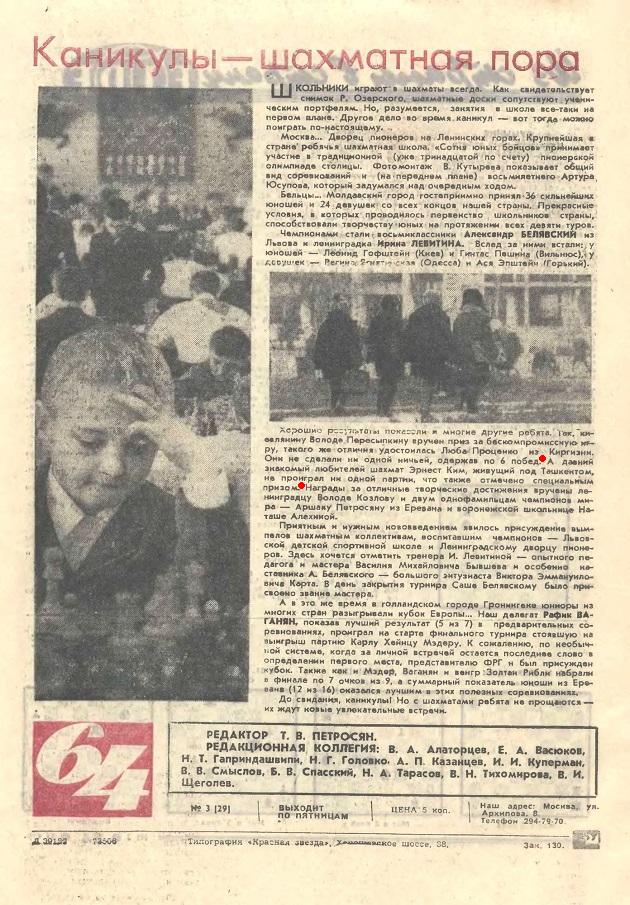

8886. Ernest Kim (C.N. 8884)

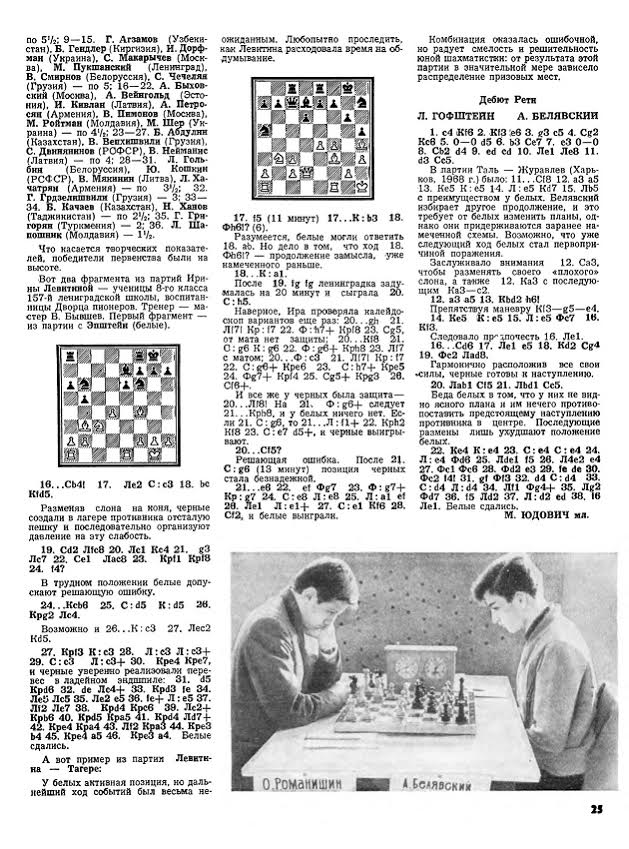

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) has found that Ernest Kim participated in the 1968-69 USSR Schools Championship. In the back-cover report in the 3/1969 issue of 64 he was described as ‘an old acquaintance of chess fans’, and it was mentioned that he received a special prize for going through the event undefeated.

Pages 131-132 of the 4/1969 issue of Shakhmaty v SSSR reported that the championship was won by Alexander Beliavsky with 7½ points from nine games, and that E. Kim of Uzbekistan finished joint fourth with six points.

8887. The BBC Genome Project

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) notes that many results can be found by searching for ‘chess’ at the website of the BBC’s Genome Project, which ‘contains the BBC listings information which the BBC printed in Radio Times between 1923 and 2009’.

8888. Frans Gunnar Bengtsson (1894-1954)

From Bradley J. Willis (Edmonton, Canada):

‘In Frans G. Bengtsson’s collection A Walk To the Ant Hill and other Essays translated by Michael Roberts and Elspeth Schubert (New York, 1951) there is an essay entitled “How I Became a Writer”. Two extracts:

“... Throughout four academic years I devoted my entire attention to the game; and few who do not play it can form any idea of the rich diversity of its pleasures, and its frightful capacity for the total absorption of its practitioners. I hoped to the last that I should turn out to have a marked talent for the game, so that I might be able to dedicate my life to a pursuit which was at once fascinating, intellectual and utterly devoid of practical utility. I have always had a certain weakness for the useless, for only the useless can have value in itself – as, for instance, a rainbow, or poetry, as to which not even the most advanced thinker can assert that their beauty is a function of their utility. Chess is by no means poor in aesthetic values; the 32 pieces and 64 squares reveal, to him who has made any progress in their mysteries, a realm of inexhaustible beauties. But the beauty of chess is far from being something merely passive: it is also living drama of the most attractive sort, with all the elements of battle – the measuring of strength, dreams of victory, breathless triumph, and black catastrophe. And all this happens while the player, emancipated from life’s vexations, sits quietly on his chair, without other bodily motion than is required to move a piece occasionally or – if one’s opponent is perceived to be sunk in gloomy meditation upon an unexpectedly threatening situation – now and then, with unruffled brow and profound satisfaction, to light a cigarette. I know but one other occupation which affords such thorough and perfect contentment as the playing of chess; and to that I shall come in a moment.

Yet when all is said and done it is conceivable that there may be some use in devoting time to chess, because of some of the lessons that are to be learned from it. A man cannot intrigue his way to a result in chess; bluff is seldom successful on the chess-board, if the players are serious, and it is impossible to win even a single game by running about corridors and keeping well in with influential people; you must play better than your opponent, and that is all. And it does not help much to try to explain away failure, false moves, and defeat; it is one’s own fault; one has one’s self to blame; one must try to play better next time. The beginner, indeed, may be visibly out of humour at a lost game, and may on occasion throw coffee-pot and control-clock at the head of the happy opponent who has so humiliatingly lured him into a trap; but the more experienced direct their displeasure and their criticism exclusively against themselves. And it may not be without a certain importance to acquire something of this attitude even to matters which have nothing to do with chess.” (Pages 272-273.)

“... After four years of University, during which I heard ten lectures, wrote a great deal of bad verse and played three or four games of chess which were good enough to be published, I fell ill ... ” (Page 274.)’

8889. Portraits and Reflections

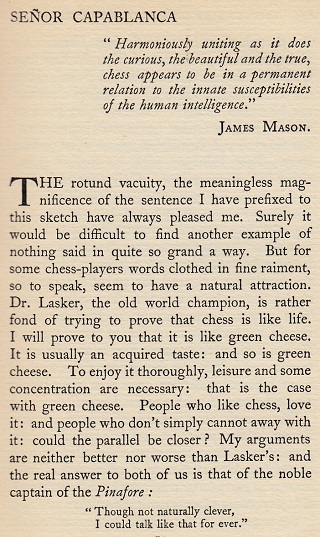

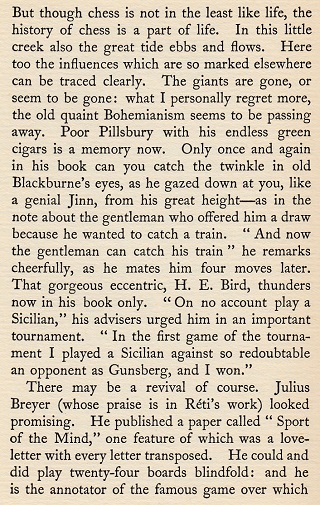

Daniel King (London) informs us that he has been reading Portraits and Reflections by Stuart Hodgson (London and New York, 1929) and, in particular, the chapter about Capablanca on pages 73-79:

C.N. 2790 (see page 312 of Chess Facts and Fables) referred to the book, in connection with the Mason quote at the start of the Capablanca chapter. A number of errors may be noted, such as the sleep story (discussed in C.N. 5118), an imagined age difference of only two years between Capablanca and Alekhine, and a misquotation on the final page reproduced above. In the Author’s Note in My Chess Career the Cuban wrote ‘conceal’, and not ‘reveal’.

The well-known figures featured in Hodgson’s book include King George V, David Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, Henry Ford, Sir Austen Chamberlain, Benito Mussolini and Sir John Simon.

Below is the obituary of [John] Stuart Hodgson on page 5 of the Manchester Guardian, 11 May 1950.

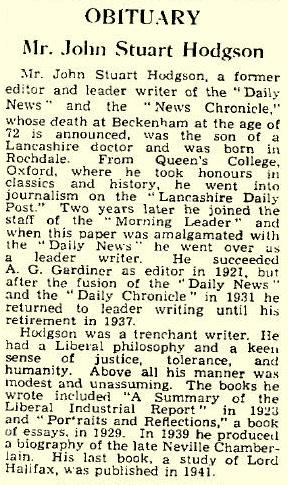

8890. Avoiding impetuosity

C.N. 7837 quoted a remark by Capablanca on page 71 of A Primer of Chess (London, 1935):

‘Do not hover over the pieces too much. It is unethical and it leads to errors. The celebrated German master, Dr Tarrasch, used to sit with his hands under his thighs to avoid hesitation and to keep from moving hastily. It is not bad to move quickly, but it is bad to move hastily.’

Did Tarrasch ever recommend the practice in his writings,

and, in any case, who was the first to make such a

recommendation?

Page 263 of book two of The Middle-Game by M. Euwe and H. Kramer (London, 1965) has the following:

‘Apart from the usual advice to weigh up everything carefully and to practise self-control, the best advice is that given by “Woodshifter”, a regular contributor to the American monthly Chess Review – “Sit on your hands!”’

For ‘Woodshifter’ read ‘Woodpusher’. The relevant ‘Tales of a Woodpusher’ article by Fred M. Wren was entitled ‘It helps to sit on your hands’ and appeared on pages 28-29 of the May 1947 Chess Review. The key section:

‘Having decided early in my chess experience never to touch a piece without moving it and never to take back a move already made, I found that, although I lost a lot of games after I learned to sit on my hands, I was also winning a lot which could easily have been lost through hurried, unconsidered moves. So, for what it is worth, here is my advice to all players who have trouble in keeping their hands off the chess pieces.

1. Sit on your hands! Yes, I mean it. Sit on them and hold them down by the weight of your body until you have decided on your move. You will not have to keep this up very long before you can give up the physical weight on your hands, as you will quickly learn to sit on them mentally, with equally good results. But, in the meantime, sit on ’em!

2. Once you have decided what move to make, take another quick look at the position, both as it is before the move and also as it will look after you have made the move. Then, if the move still looks best to you, make it and abide by the results.

Never take a move back. If you adopt this practice in skittles and friendly play, you will never have any trouble on this point in match or tournament play.’

Source: Chess Review, May 1947, page 29

8891. Goethe (C.N. 5901)

In an article ‘The geek defence’ on page 9 of the Radio Times, 25-31 October 2014 Dominic Lawson refers to ‘chess – the game Goethe described as “the touchstone of the intellect”’. However, C.N. 5901 showed that there are complications with this quotation when Goethe’s writings are examined.

What is the earliest known appearance of the specific wording ‘the touchstone of the intellect’ to describe chess? An uninformative example is on page 7 of The Chess-player’s Week-end Book by R.N. Coles (London, 1950):

‘The game of chess is the touchstone of the intellect. Goethe.’

8892. Accepting correction

On 6 September 2014 a contributor to the English Chess Forum drew attention to the BCM’s poor online presentation of an excellent article by G.H. Diggle published by the magazine in 1955. Even today, despite a prompt from the contributor after a six-week wait, obvious repair work to the online version of the article is still required.

In 1955 the Editor of the BCM was Brian Reilly. His practice was to accept correction graciously.

8893. The New York Times

Another locale where interesting material is interspersed with bilge is ChessBase.com, and, to mention a recent example, the ‘Discuss’ section on chess coverage in the New York Times. The underlying issues (the future of chess columns in newspapers and online editions thereof, the possible inter-relationship between formal columns, feature articles and other outlets, the combination or separation of news and comment, and the credentials of chess columnists) are of great importance and require serene treatment on a forum uninterrupted by precipitant submissions of the ‘here’s-my-two-cents’-worth’ variety.

In any case, chess can ill afford to lose a journalist as conscientious and fair-minded as Dylan McClain.

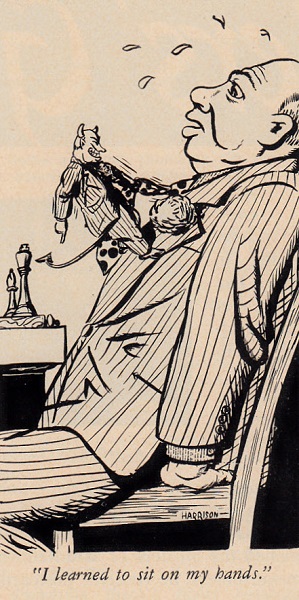

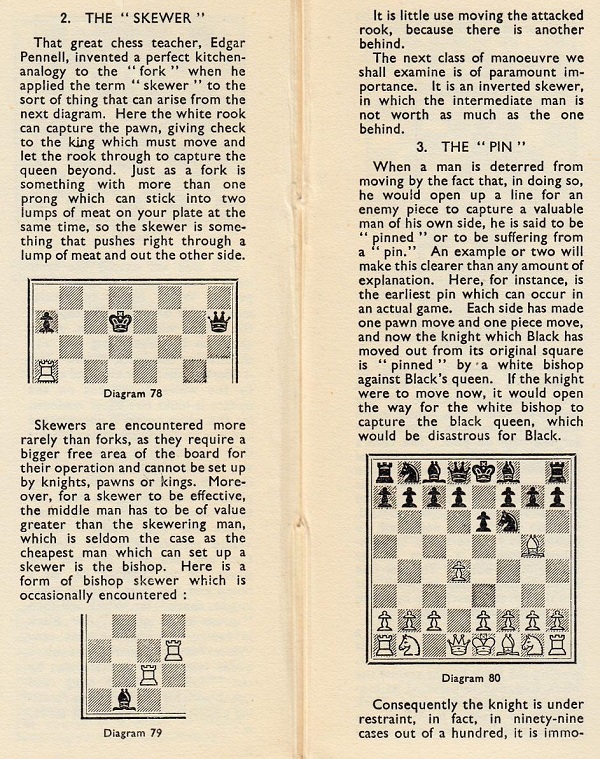

8894. What is a skewer?

As reported in C.N. 74 (see Chess Jottings), page 94 of Chess by Paul Langfield (London, 1978) had the following in its Glossary:

‘Skewer: an attack on a piece which is beyond the piece occupying the square attacked.’

A similar indigestible wording was on page 54:

Those who have seen the book may be unsurprised by the suggestion that White can extricate himself from the skewer by playing his queen to a square defended by a black piece.

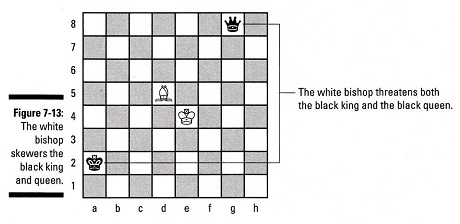

An additional alleged kind of skewer (‘when the attacking piece is between the two defenders’) was discussed by James Eade on pages 108-109 of Chess for Dummies (Hoboken, 2011):

Most writers would call this a bishop fork.

Two definitions of ‘skewer’ from reference books:

- ‘A term applied to an attacking position in which a piece is held in a position so that it can be captured as soon as a more valuable chess unit moves out of the line of attack. Hence the real target is not the piece immediately attacked but the second piece stationed on the same line behind it. A skewer is the opposite of a pin.’

Source: page 188 of Dictionary of Modern Chess by Byrne J. Horton (New York, 1959).

- ‘A tactical manoeuvre in which a piece is attacked and forced to move out of the way to protect itself, allowing a second and less valuable piece to be captured. The skewer is the opposite of the pin.’

Source: page 261 of An illustrated Dictionary of Chess by Edward R. Brace (London, 1977).

Such definitions pass over the eventuality that the defender’s two pieces have the same value. On pages 37-38 of The Inner Game of Chess (New York, 1994) Andrew Soltis referred to the threat of the ‘Bd6 skewer’ after 36 Bf4 in Kasparov v Lutikov, Minsk, 1978:

Soltis also quoted a remark of Kasparov’s about the position, naturally without giving the source, i.e. page 3 of The Test of Time (Oxford, 1986).

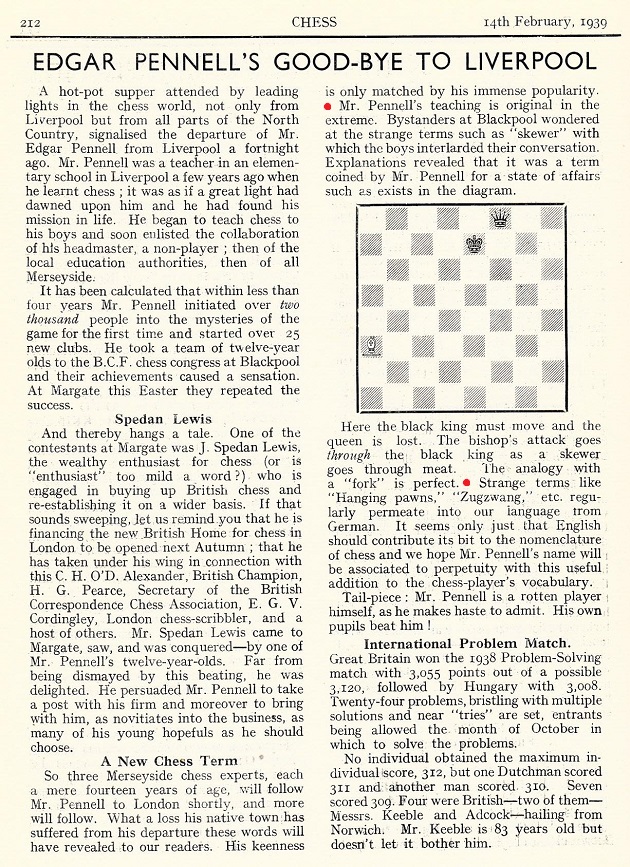

As regards the origin of the term ‘skewer’, we show the full text of an article referred to in C.N. 3061:

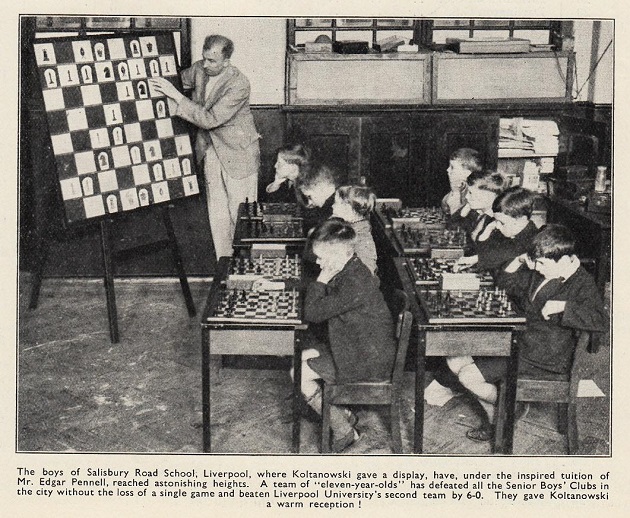

A photograph from page 275 of CHESS, 14 April 1937:

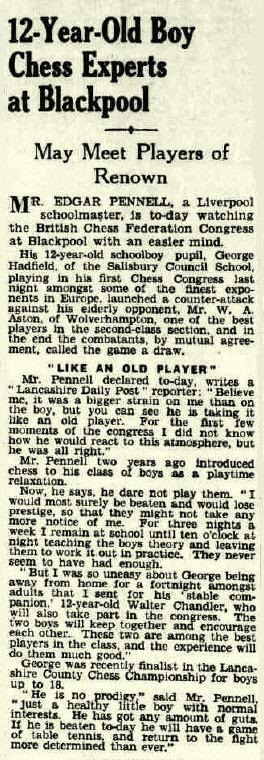

Below is a report about Edgar Pennell on page 7 of the Lancashire Evening Post, 6 July 1937:

Further information about Pennell and George Hadfield was published on page 454 of CHESS, 14 August 1937.

On page 10 of The Times, 23 October 1976 Harry Golombek referred to Pennell’s contribution to chess in Liverpool:

‘There is the astonishing Edgar Pennell, himself (I hope he will forgive me) rather a weak player, but a wonderful teacher of the game and the originator of the great series of chess congresses for children in Liverpool where their numbers have risen to over 1,000 a year.’

Pennell was mentioned in the section on the skewer on pages 48-49 of Easy Guide to Chess by B.H. Wood (Sutton Coldfield, 1942):

Wanted: further occurrences of the chess term ‘skewer’ before publication of Wood’s book, and particularly from the 1930s. Existing C.N. items on the theme have been gathered together in our latest feature article, The Chess Skewer.

8895. Ad libitum

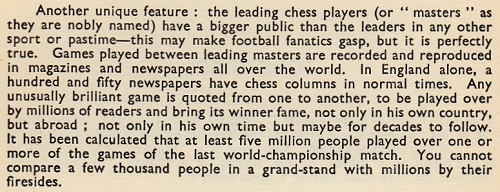

From page 6 of the first edition of B.H. Wood’s Easy Guide to Chess (Sutton Coldfield, 1942):

A sentence which stands out:

‘It has been calculated that at least five million people played over one or more of the games of the last world championship match.’

Calculated how, and by whom?

100% of statistics about the popularity of chess should be distrusted by 100% of chess writers.

8896.

Tschigorinsky (C.N. 8879)

The full text of Sam Loyd’s puzzle, including the answer, from the 22 November 1905 edition of the Chicago Daily News:

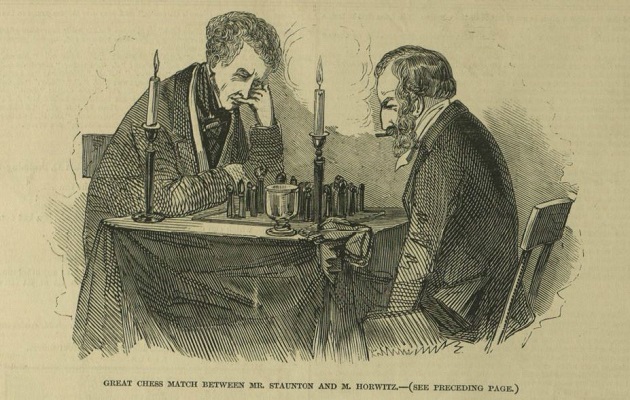

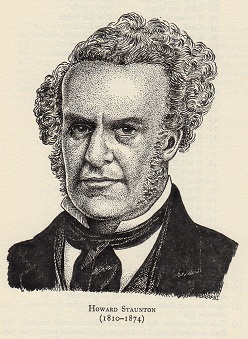

8897. Depictions of Staunton

From Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England):

‘Regarding the monochrome picture of Staunton and Horwitz which you have reproduced in Pictures of Howard Staunton from Deutsches Wochenschach, 2 October 1910, I have a tinted copy with, pasted on the back, a small cutting from the Illustrated London News which specifies the date 7 February 1846:’

The picture was published on page 100 of that issue of the Illustrated London News, with a reference in the caption to Staunton’s chess column on page 99:

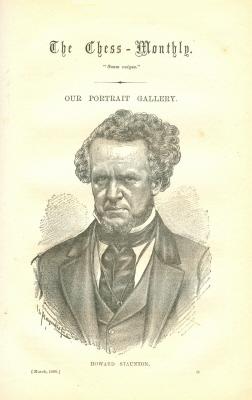

Another illustration (‘Four’) in the Staunton feature article was discussed in C.N.s 5998 and 6015. In the former item a correspondent suggested that the artist’s signature seemed to read ‘Maguille’, and in the latter we noted that the picture had appeared in the Chess Monthly in 1890.

Source: page 164 of A Century of British Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1934)

Source: page 193 of Chess Monthly, March 1890

‘Pictures of Howard Staunton’ also mentions that a similar sketch, by Alexander Forrest, was published on page 70 of The Chess-player’s Week-end Book by R.N. Coles (London, 1950):

Coles’s book had illustrations by Forrest of 11 masters: Philidor, Labourdonnais, Anderssen, Lasker, Alekhine, Euwe, Botvinnik, Staunton, Steinitz, Capablanca and Morphy.

Mr Clapham now adds:

‘Although the sketch by Forrest is indeed very similar to the “Maguille” picture, there are significant differences, concerning the beard, sideburns, neck-ribbon and lapels. Variations in the eyes, eyebrows and lips give a different overall expression.

The “Maguille” picture is on page 170 of Howard Staunton Uncrowned Chess Champion of the World by Bryan M. Knight (Montreal, 1974) with the caption “Howard Staunton – circa 1840”.

The Forrest sketch is on the back of the dust-jacket of the Batsford reprint (London, 1985) of Staunton’s The Chess-Player’s Handbook. Elsewhere the dust-jacket states, without any mention of Forrest or Coles:

“The drawing of Howard Staunton on the back cover was produced [sic] by courtesy of Brian Reilly.”’

8898. Maxim about

P-KB4 (C.N. 5857)

C.N. 5857 asked for information about ‘It is always too early for P-KB4’, described as a ‘maxim by a well-known foreign Master’ on page 18 of One Hundred Chess Maxims by C.D. Locock (Leeds, 1930).

From pages 18-19 of Technique in Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1961):

‘... the late F.D. Yates, a great ornament of British Chess, used to describe P-KB4 as “a move that is always too early”. That did not prevent him from playing it often enough. On occasion he played it too early for his opponent.’

8899. J.C.J. Wainwright

On pages 152-155 of the July-August 1921 American Chess Bulletin Henry W. Barry wrote an ‘In Memoriam’ tribute to the problemist Joseph C. J. Wainwright. From page 155:

‘He was one of the earliest American writers of chess stories, generally of a romantic vein. One of the lengthiest chess tales extant, “The Two Knights Defense”, won him the prize in the Hartford Times Literary Chess Tourney in 1878.

He wrote many chess poems, his finest in this direction being his well-known “Sonnets to the Chess Pieces”.’

Wainwright’s fiction and poetry were discussed on the last two pages of an article about him in the September 1892 American Chess Monthly (pages 163-169). For example:

‘Although not strictly the originator, our friend was certainly one of the earliest American writers who launched out into the production of chess stories. Romance was the vehicle in which he gaily rode his choicest problems. Caïssa held the ribbons and drove Love and Adventure in tandem. His most pretentious narrative, in several chapters, is “The Two Knight’s [sic] Defense”, a story of the times of Richard I, when chess was supposed to have been first introduced into England. It was the prize tale in the Hartford Times Literary Chess Tourney, 1878, and is probably the lengthiest story extant, devoted exclusively to Caïssan themes.’

From page 68 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1 March 1878:

‘The awards of the judges in the Hartford Times Literary Chess Tourney have been announced. The authoress of the prize poem, “The Final Mate”, is Mrs Hazeltine, better known to the chess world as “Phania”. The author of the prize story, “The Two Knights’ Defence”, is Mr J. Wainwright, of Walpole, Massachusetts. The gentleman who carried off the honours in the essays, with a composition entitled “The World’s Chess Champions”, is M. Delannoy, a Frenchman resident in London.’

Did the Hartford Times publish any of the entries?

Page 168 of the September 1892 American Chess Monthly stated with regard to Wainwright:

‘He was also a Knight of Belden’s Round Table, in the ever glorious chess symposia of the old Hartford Times days, letting fly with fearless accuracy his epistolary arrows, and defending his pet ideas and productions against all-comers. Those keen mental jousts were worth a dozen modern tournaments, as far as analysis goes, in constraining a composer to distill the rarest wine of his critical genius.’

Source: American Chess Bulletin, July-August 1921, page 153.

| First column | << previous | Archives [123] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.