Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [124] | next >> | Current column |

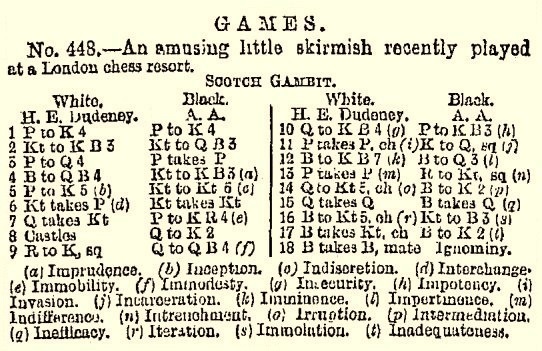

8900. From imprudence to ignominy

A game won by Henry Ernest Dudeney (1857-1930) was annotated in original style on page 7 of the Leeds Mercury Weekly Supplement, 23 October 1886:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Nf6 5 e5 Ng4 6 Nxd4 Nxd4 7 Qxd4 h5 8 O-O Qe7 9 Re1 Qc5 10 Qf4 f6 11 exf6+ Kd8 12 Bf7 Bd6 13 fxg7 Rg8 14 Qg5+ Be7 15 Qxc5 Bxc5 16 Bg5+ Nf6 17 Bxf6+ Be7 18 Bxe7 mate.

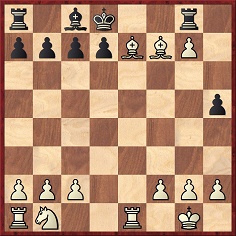

8901. Hanham v Pollock, Nottingham, 1886

From page 33 of London Feb/Mar 1886 and Nottingham 1886 by A.J. Gillam (Nottingham, 2007):

Since ‘The Field’ and ‘another source’ are the sole information offered, and there is no mention of the straightforward mate in four (22...Qxf2+), further details will be appreciated.

8902. More theft

As recorded in Copying, our work has often been misappropriated. The latest case is ‘chess history’ (‘Sabrina Sörensen’), a website which has stolen a colossal amount of material from Chess Notes.

[Two or three weeks later the offending site became inaccessible.]

8903. Compilation of political articles

by Kasparov

We have received two translations of Kasparov’s political articles, Poutine: des Jeux et des geôles (Paris, 2014) and Scacco matto a Putin (Milan, 2014). The back cover of the former book gives the flavour:

The overwhelming impression gained, as ever, is that the author’s proper place is at the chess board. Among the masters, Kasparov seems the most politically minded and the least politically adept.

8904. The value of pieces (C.N. 8885)

A further contribution from Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) on the value of the chess pieces:

‘Page 137 of Games and Sports by Donald Walker, published in 1837 by Thomas Hurst, London, suggests a scale of values for chess pieces. The relevant section reads:

“The values of the men – These have been calculated as merely regulating the odds sometimes given at the beginning of the game; for their value during the game must depend greatly on situation. The value of the pawn being taken as one; the knight is worth rather more than three; the bishop is of similar value; the rook is worth about five pawns, or two pawns and a knight or bishop; the queen is worth about ten pawns, and is therefore the most powerful of the pieces.”

‘However, on page 138 it is stated that the queen’s relative value is diminished toward the end of a game, when rooks have a “clearer” board and thus more power relative to the queen.’

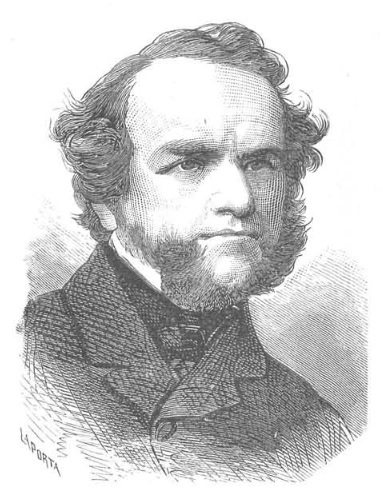

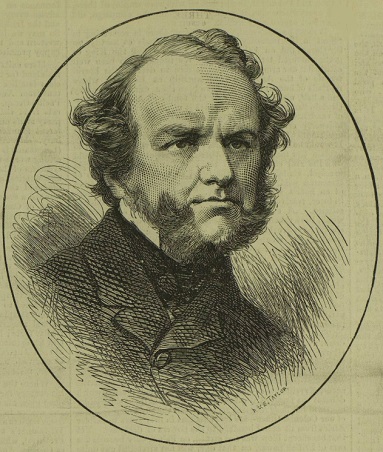

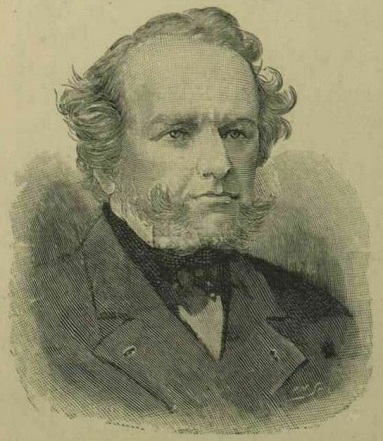

8905. Staunton

Juan Carlos Sanz Menéndez (Madrid) points out that an illustration which is slightly different from numbers seven and twelve in Pictures of Howard Staunton appeared on page 479 of the Madrid publication La Ilustración Española y Americana, 15 August 1874. It is shown below, followed by the other two, which were given in the Illustrated London News in 1874 and 1892 respectively:

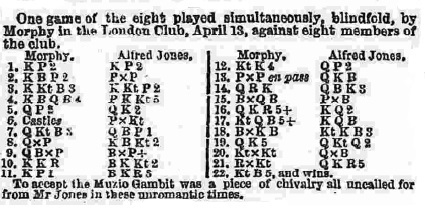

8906. Morphy v Jones

From Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada):

‘One would expect the identities of players in as important an event as Morphy’s blindfold exhibition at the London Chess Club on 13 April 1859 to be well established, but that is not the case for one of his opponents, who is referred to in many sources only as “Jones”.

On page 187 of Morphy’s Games of Chess (London, 1916) P.W. Sergeant gave his name as “J.P. Jones”, as did David Lawson’s biography of Morphy. However, on page 8 of the 17 April 1859 edition of Bell’s Life in London George Walker, who took a board in the display, identified him as “Alfred Jones”. Walker also wrote “Alfred Jones” when he published the game on page 3 of the 19 June 1859 issue of Bell’s Lif e in London:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 g4 5 d4 Qe7 6 O-O gxf3 7 Nc3 c6 8 Qxf3 Bg7 9 Bxf4 Bxd4+ 10 Kh1 Bg7 11 e5 Bh6 12 Ne4 d5 13 exd6 Qf8 14 Rae1 Be6 15 Bxe6 fxe6 16 Qh5+ Kd7 17 Nc5+ Kc8 18 Bxh6 Nf6 19 Qe5 Nbd7 20 Nxd7 Qxh6 21 Rxf6 Qh4 22 Nc5 and wins.

Data on J.P. Jones and Alfred Jones would be appreciated, as would information on how the discrepancy arose.’

On page 104 of Morphy Gleanings (London, 1932) P.W Sergeant noted, without further comment, that Bell’ s Life in London had called Morphy’s opponent ‘Alfred Jones’. That was also the name given in other newspaper reports on the exhibition, e.g. the London Daily News, 20 April 1859, page 2, and the Times, 21 April 1859, page 12.

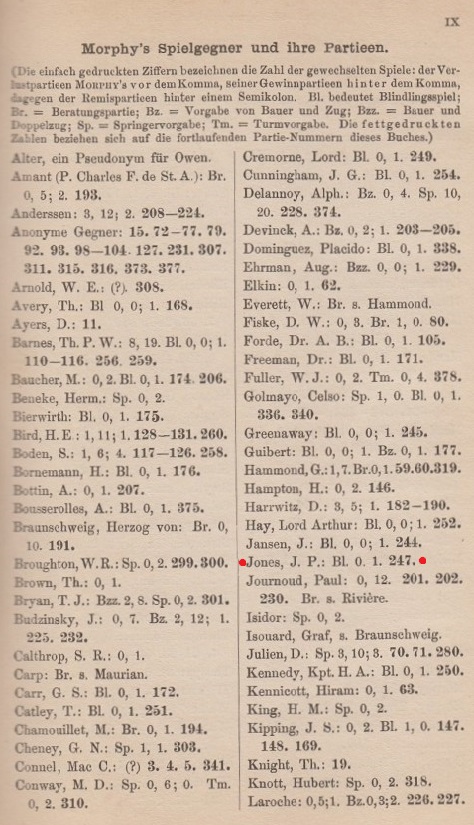

The provenance of ‘J.P. Jones’ is unclear, but two pre-Sergeant sightings can be mentioned: page ix of Paul Morphy Sein Leben und Schaffen by Max Lange (Leipzig, 1894) and page 290 of Paul Morphy by Géza Maróczy (Leipzig, 1909). The former book had ‘Jones, J.P.’ in the index on page ix:

Confusion over players’ initials is not limited to Jones. Two of Morphy’s other opponents in the London display were indexed in Max Lange’s book (page x) as ‘Maude P.’ and ‘Slous, P.’, whereas Lawson’s biography (page 193) and other sources give their initials as G. and F.L. respectively.

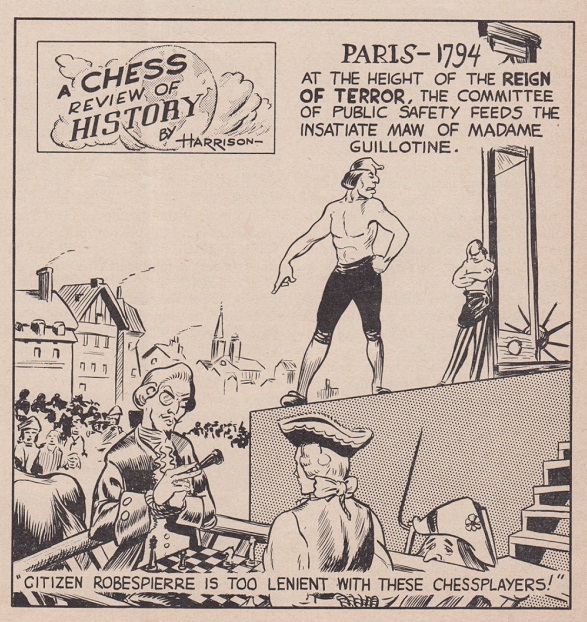

8907. Thomas Paine and Robespierre (C.N.s 6361 & 6374)

From page 11 of the January 1949 Chess Review:

8908. Abrahams quotes

- ‘The richest chess is seen when cleverness follows

cleverness; when during, or after, a fairly logical

process, an ingenious idea intrudes, and is met by an

ingenious idea, and so on. That means that both players

are exploiting the hidden resources of the board.’

Source: page 133 of Teach Yourself Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1948).

- ‘The highest type of chess is that in which the winner wins by exploiting the minimum of weakness; and does so in the nearest possible approximation to a continuous movement.’

Source: page 125 of The Chess Mind by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1951).

- ‘Much of chess is in the nature of petty larceny, to say nothing of catching bargains, and the picking up of unconsidered trifles. One element in technique is the familiarity with devices that achieve these processes neatly, if not surreptitiously.’

Source: page 199 of Technique in Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1961).

- ‘If chess has social merits (you may have heard this denied) one of them must be the sense of participation that possesses the players. Every player is engaged in every other player’s game.’

Source: page 92 of Test Your Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1963).

- ‘Concentration is, perhaps, the most important word in

any account of how to learn chess, or how to learn

anything. Concentration is learnable, but unteachable.’

Source: page 8 of The Handbook of Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1965).

- ‘Good moves win; good positions don’t win.’

Source: page 49 of Not Only Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1974).

- ‘The essence of beauty in chess is “pattern” or “form”, which is not the purpose of play. “Surprise” is irrelevant.’

Source: page 32 of Brilliance in Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1977).

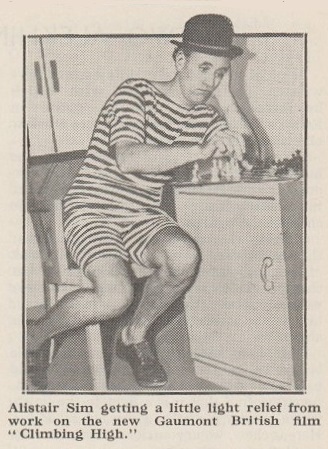

8909. Alastair Sim (1900-76)

The earliest chess-related photograph of Alastair Sim that we recall comes from page 63 of CHESS, 14 October 1938:

8910. Morphy v Jones (C.N. 8906)

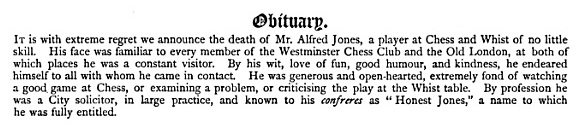

Whereas no reference to a player called J.P. Jones has been found, many appearances of the name Alfred Jones can be cited. For example, John Townsend (Wokingham, England) refers to an account of the ‘Annual Dinner of the London Chess Club’ on page 14 of the Era, 28 May 1865:

‘The chair was occupied by A. Mongredien, Esq., President of the Club; and the vice-chair by Alfred Jones, Esq.’

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) notes an obituary of Alfred Jones on page 180 of the Westminster Papers, 1 March 1870:

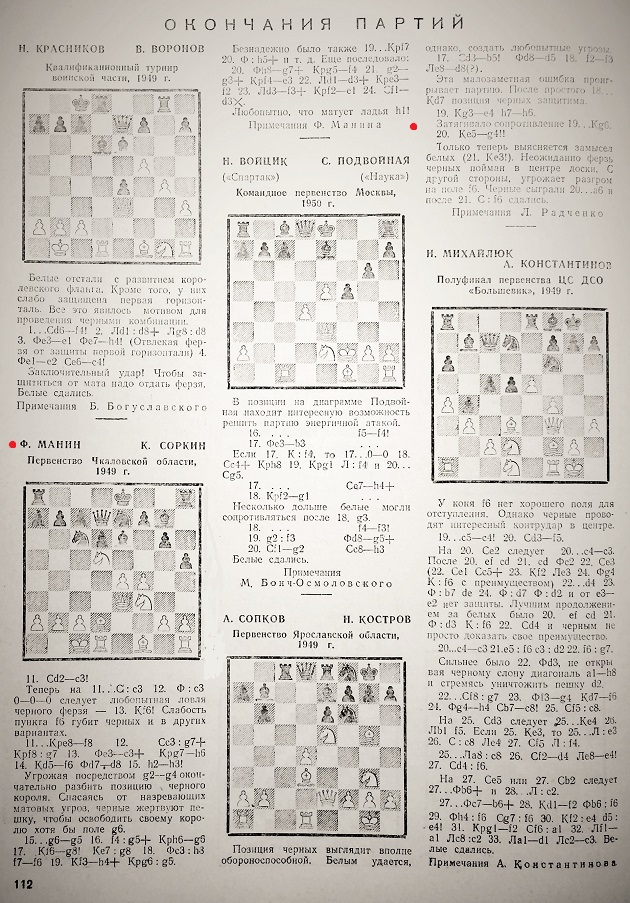

8911. Manin v Sorkin

A further specimen in the category Royal Walkabouts (Manin v Sorkin, Chkalovsky, 1949) is provided by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) from page 112 of the 4/1950 Shakhmaty v SSSR:

11 Bc3 Kf8 12 Bxg7+ Kxg7 13 Qc3+ Kh6 14 Nf6 Qd8 15 h3 g5 16 fxg5+ Kg6

17 Ng8 Nxg8 18 Qxh8 f6 19 Nh4+ Kxg5 20 Qg7+ Kf4 21 g3+ Ke3 22 Rd3+ Kf2 23 Rf3+ Ke1

24 Bd3 mate.

As regards the missing opening moves, our correspondent points out that the position after Black’s tenth move occurred in Chigorin v Mackenzie, Vienna, 1882 with one exception: Mackenzie played 10...O-O-O and did not move his h-pawn. Source: pages 152-154 of Das II. Internationale Schachmeisterturnier Wien 1882 by C.M. Bijl (Zurich, 1984).

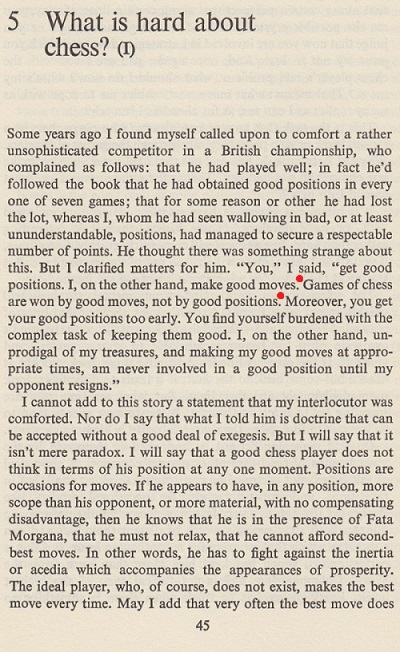

8912. Abrahams quote (C.N. 8908)

C.N. 8908 quoted from page 49 of Not Only Chess (London, 1974) Gerald Abrahams’ observation ‘Good moves win; good positions don’t win’.

On page 45 of the same book Abrahams cited a conversation with another player ‘some years ago’:

‘But I clarified matters for him. “You”, I said, “get good positions. I, on the other hand, make good moves. Games of chess are won by good moves, not by good positions. Moreover, you get your good positions too early. You find yourself burdened with the complex task of keeping them good. I, on the other hand, unprodigal of my treasures, and making my good moves at appropriate times, am never involved in a good position until my opponent resigns.”’

For the context, the full page is shown:

On page 106 of Not Only Chess Abrahams expressed the same sentiments in yet another wording:

‘The preparer got a good position. But good positions do not win games. Games are won by good moves, by many good moves, in conjunction with the opponent’s bad moves.’

Substantiation is sought of the most common version of the quote attributed to Abrahams, e.g. by Andrew Soltis on page 20 of The Wisest Things Ever Said About Chess (London, 2008):

‘As Gerald Abrahams had said, “Good positions don’t win games. Good moves do.”’

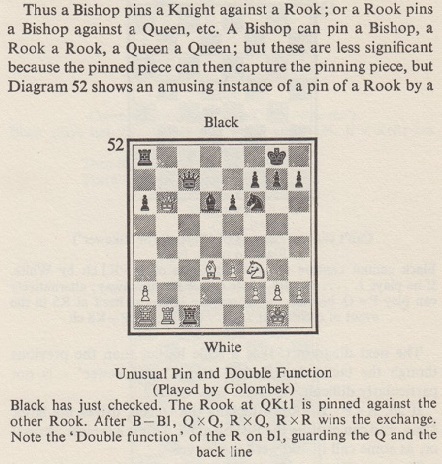

8913. Abrahams v Golombek (C.N. 8842)

As shown in C.N. 8842, this was the final position in Abrahams v Golombek, Hastings, 1948:

On page 67 of The Handbook of Chess (London, 1965) Abrahams gave a different position and named only Golombek:

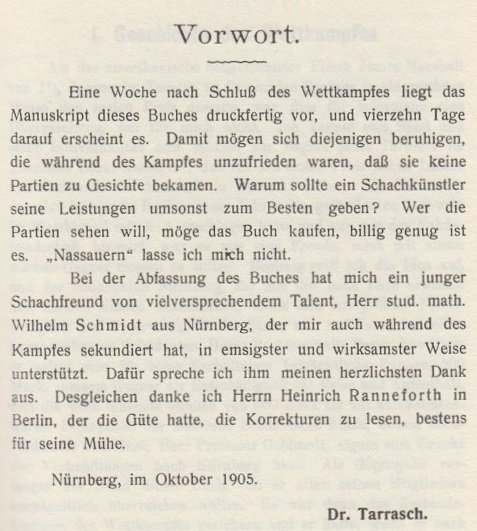

8914. ‘Instant books’

It may be imagined that ‘instant books’ on chess matches are a modern development, but the first sentence in the Foreword to Tarrasch’s 62-page work Der Schachwettkampf Marshall-Tarrasch im Herbst 1905 (Nuremberg, 1905) reported that the manuscript was ready for printing one week after the match ended and that the book appeared a fortnight later:

8915. Morphy v Jones (C.N.s 8906 & 8910)

From William D. Rubinstein (Melbourne, Australia):

‘His name makes precise identification difficult, but he is presumably the Alfred Jones of 7 (other sources state 72) Queen Street, Cheapside, City of London and 117 Harley Street, Middlesex, “gentleman”, who died on 29 January 1870 at 117 Harley Street, leaving £35,000 (resworn from £30,000). His executors were his sister Mary Shephard Jones of 117 Harley Street and his brother Horace Jones of 13 Victoria Street, Middlesex. Oddly, I could find no death notice for Alfred Jones, and could not trace him in the Census, and do not know his age at death. His brother Horace Jones was almost certainly Sir Horace Jones (1819-87), the architect who designed Tower Bridge and was President of the Institution of British Architects in 1882-84 and was knighted in 1886. (Information from ancestry.co.uk and the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.)’

8916. New York, 1924

Wanted: the newspaper article referred to by Edward Lasker on page 159 of Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood (Philadelphia, 1942):

‘As Horace Bigelow, who covered the tournament for one of the New York papers, remarked at the time: “The modern school came, saw and succumbed.”’

From page 92 of Lasker’s The Adventure of Chess (New York, 1950):

‘... the amusing though erroneous comment of a chess columnist was: “The New School came, saw, and succumbed.”’

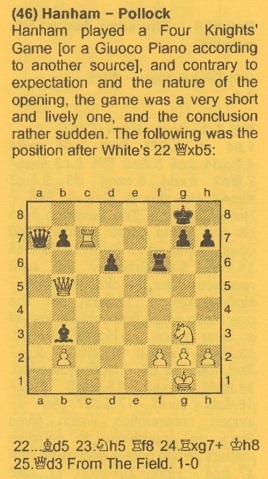

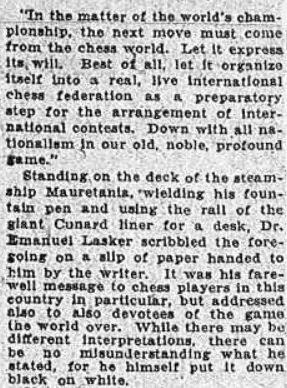

8917. Chicago, 1933

White to move

This famous position (11 Qxh7+) comes from a game extensively discussed in Chaos in a Miniature (Edward Lasker v George Thomas, London, 1912), but a noteworthy addition is that two decades later Lasker played it with the black pieces.

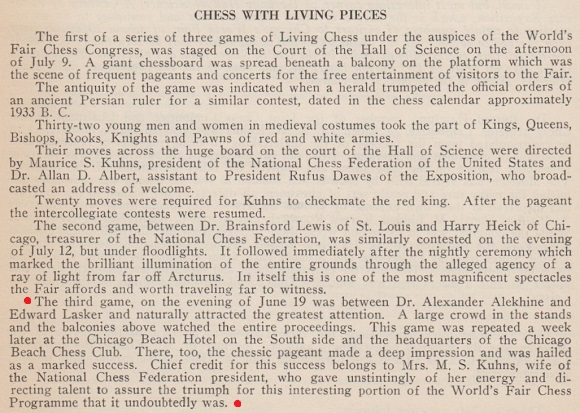

First, an extract from page 109 of the American Chess Bulletin, July-August 1933:

And from page 4 of the September 1933 Chess Review:

‘... on the evening of 19 June came the awaited meeting between Dr Alekhine and Edward Lasker. This naturally drew the largest gathering of any single chess event with the exception of the blindfold display. Alekhine won in good style, but the game itself was less important to the audience than the idea of the spectacle. This game was repeated later at the Chicago Beach Hotel.’

Neither US magazine gave the moves of the Alekhine v Lasker game, which in any case was pre-arranged. From pages 160-161 of Lasker’s The Adventure of Chess (New York, 1950):

‘In a chapter on eccentricities of the game, Liddell’s book [Chessmen by Donald M. Liddell (New York, 1937)] brings a picture of a board with living pieces used in a game played in the open-air amphitheater of the Century of Progress Exposition at Chicago, in 1933. I happened to direct that game, and the picture recalled to my mind a tragicomic incident which occurred toward the end of it. The chess pieces were mostly boys and girls from Chicago high schools, dressed in real old-Indian costumes. On the day of the game a bright, hot sun was shining, and over 5,000 onlookers crowded every available spot in the arena. To the majestic tune of a march especially composed for the occasion by the well-known composer DeLamarter, who was a resident of Chicago, the chess pieces, in impressive array, descended a wide stairway and took their places on the board. The world champion, Alekhine, had been engaged for the occasion to play the game with me which the living pieces were to show, and a tower was provided from which Alekhine and I called our moves through megaphones. To make sure that the performance would not take more than an hour at most, we had decided to select a short game with which we were both familiar, rather than actually engaging in a contest ourselves. The choice of the committee had fallen on a rather well-known game which I had won some 20 years previously against the British champion, Sir George Thomas. Alekhine agreed, but insisted that he should play the winning side. Everything went fine for about a half hour, when suddenly my queen’s rook’s pawn fainted. The poor fellow had been standing motionless in the hot sun all that time, and instead of making it known to someone that he was feeling ill, he held out bravely until he finally collapsed. He was carried out on a stretcher and replaced by an “understudy” whom we had held in readiness in case one of the actors did not show up.

I doubt that a very large percentage of the crowd knew chess, but the colorful spectacle certainly served as a spellbinding introduction to learning the game.’

Below is the photograph mentioned by Lasker, as published opposite page 98 of Liddell’s book (and between pages 132 and 133 of the London, 1976 edition):

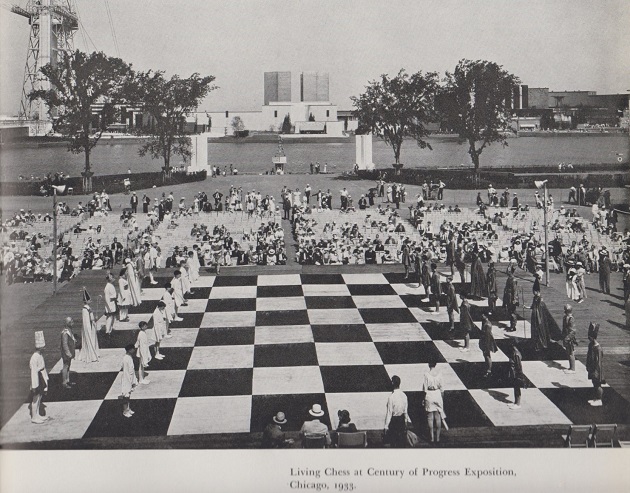

8918. Nationalism

A remark by Emanuel Lasker:

‘Down with all nationalism in our old, noble, profound game.’

Source: Hermann Helms’ chess column on page A3 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 12 June 1924:

We first quoted the observation by Lasker in C.N. 1158 (see page 264 of Chess Explorations), from page 318 of the August 1924 BCM.

8919. Grievance

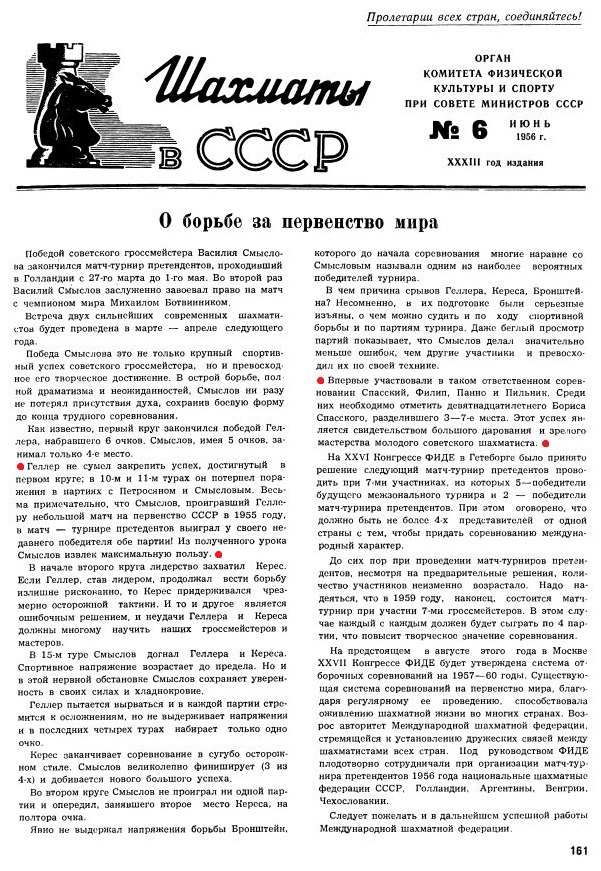

Petrosian’s Games refers to the master’s reaction to press coverage of his performance at Amsterdam, 1956, and below are his comments in full, from pages 215-216 of the Shekhtman book discussed in our article:

‘That same year [1956] an article appeared in the magazine Shakhmaty v SSSR, where the performances of the participants in the Amsterdam Candidates’ tournament were analyzed. I had not played badly there: out of the ten participants I had shared 3rd-7th places. But the article discussed the creative achievements of only nine grandmasters – from the winner, Smyslov, to Pilnik, who brought up the rear. I was not even mentioned – it was as though I had not even played in the tournament.

I must confess that this so wounded me that I began seriously wondering whether I shouldn’t give up chess.’

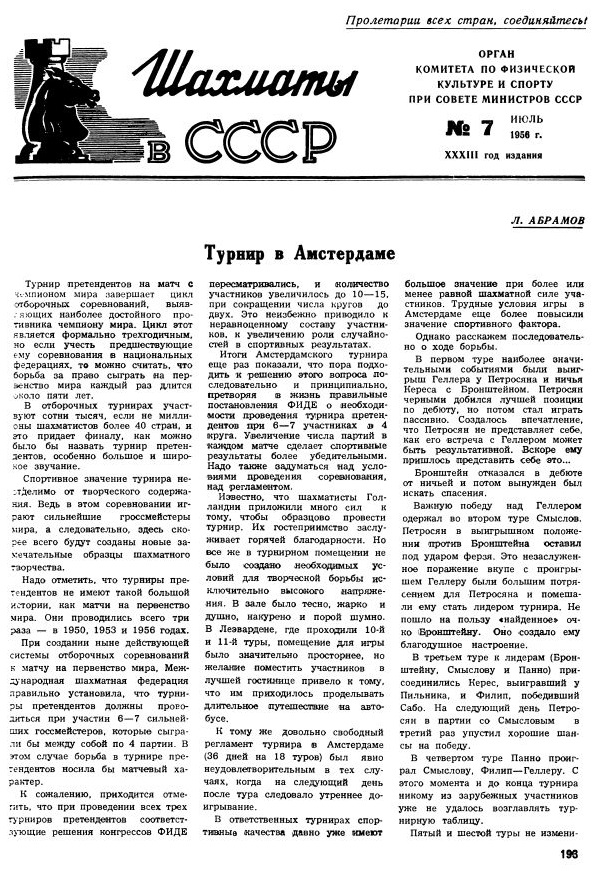

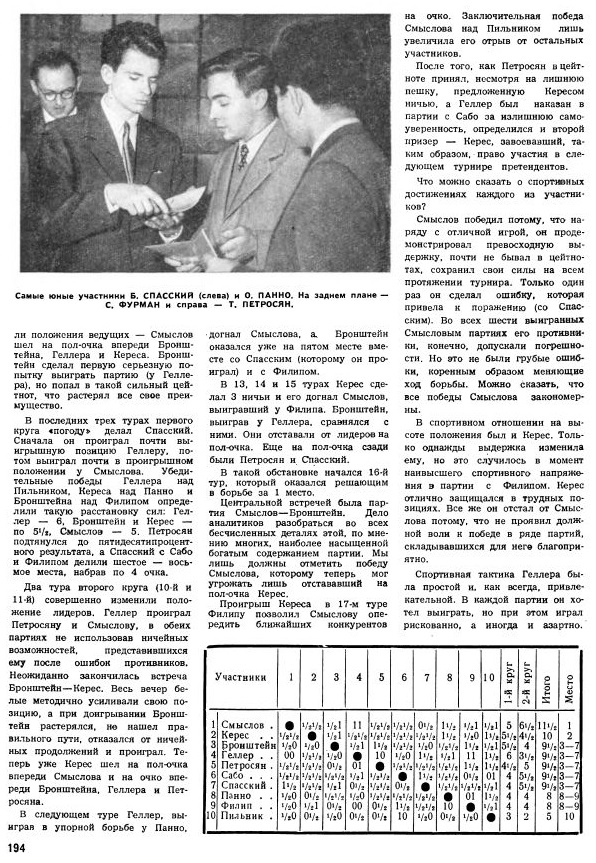

Timothy J. Bogan (Chicago, IL, USA) asks what exactly appeared in Shakhmaty v SSSR, and we are grateful to Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) for providing page 161 of the 6/1956 issue (Editor: V. Ragozin). The unsigned editorial contained one mention of Petrosian, in the fifth paragraph. Later, it discussed the other four players who shared third place with him (the four being singled out as newcomers to that level of competition):

Mr Scoones has also forwarded an article about the tournament by L. Abramov on pages 193-195 of the 7/1956 magazine. It included a brief discussion of Petrosian’s performance on page 195:

8920. Steinitz and God

From page 14 of A Book of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1973):

‘Overall, chessplayers are much less odd than is generally supposed. It is unfortunate that Fischer is such an extreme type; his unbalanced behaviour has inevitably encouraged journalistic muck-raking for other eccentricities amongst chess masters. I find the references to Steinitz and his statement that he could give God odds at chess particularly repugnant; Steinitz’s mind broke down when he was old, ill, unhappy and within a year of his death. It is as misleading as it is heartless to represent his conduct then as if it were his normal behaviour.’

8921. A Spassky book

‘Turgid’ is hardly a word applicable to Boris Spassky, but it is a charitable description of the prose in Winning Record against World Champions by B. Spassky and I. Gelfer (Rosh Ha’ayin, 2014). Below, for instance, is the start of the former world champion’s Preface:

The entire humdrum book (which misappropriates a number of photographs from C.N. – see, for example, pages 15, 190 and 203) should obviously have been revised by a writer of English mother tongue.

That said, in some respects the prose is hardly worse than the offerings of certain chess writers whose first, and perhaps only, language is ostensibly English. The following comes from a report at The Week in Chess on the seventh match-game between Carlsen and Anand, 17 November 2014:

‘The remaining game was difficult and complex but remained generally rather uninteresting because Anand played really rather well.’

[Shortly after the present item was posted, the above sentence was changed at The Week in Chess, although the improvement was not great: ‘The rest of the game was difficult and complex and Anand played it really rather well.’]

8922. Eye patches

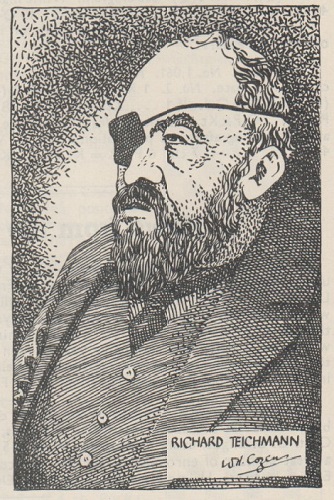

From the first page of an article by Fred Reinfeld, ‘At What Age is a Chess Master at his Best?’, on pages 249-253 of CHESS, 14 March 1936:

‘Teichmann, who had only one eye, was famous both for his laziness and for the rather large percentage of blunders in his games. My impression of Teichmann’s play underwent a radical change when, through a mishap in the Syracuse, 1934 tournament, I was forced to play my last game with a patch over one eye. I have spent many a pleasant time at the chess board, but never have I endured four such agonizing hours as in that game where I had the use of only one eye. Since then I have had a tremendous admiration for Teichmann, and my vivid realization of his dreadful handicap has enabled me to understand his readiness to take a premature draw. The chronicle of human achievement does not include any more heroic deed than Teichmann’s first prize in one of the strongest tournaments in chess history (Carlsbad, 1911), with his fine victories in this protracted contest over Alekhine, Nimzowitsch, Schlechter, Rubinstein, Tartakower, Kostić, Spielmann – to mention only the most outstanding rivals.’

An illustration by W.H. Cozens on page 316 of the November 1961 BCM:

Another player who had occasion to wear an eye patch was Emanuel Lasker, during his autumn 1909 contest against Dawid Janowsky; see the photograph in our article Lasker v Janowsky, Paris, 1909.

Lasker had undergone an operation on his right eyelid, as reported on page 407 of La Stratégie, November 1909:

‘Le Dr. E. Lasker, bien que handicapé par les suites d’une opération subie à la paupière de l’oeil droit, a brillamment maintenu sa renommée en gagnant sept parties contre une perdue et deux nulles.’

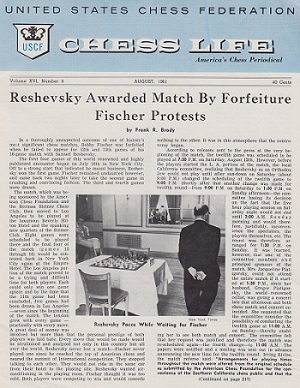

8923. A flood of letters

Concerning the 1961 match between Fischer and Reshevsky, aborted in a scheduling dispute when the score was level after 11 games, Frank Brady wrote on page 55 of Profile of a Prodigy (New York, 1965):

‘The Fischer-Reshevsky hassle brought the greatest flood of letters ever to inundate Chess Life – well over a thousand to a magazine whose entire circulation was only about six thousand. Almost all the mail was pro-Fischer, in marked contrast to his bad press elsewhere.’

At the time, Frank Brady was the Editor of Chess Life.

8924. Morphy v Jones (C.N.s 8906, 8910 & 8915)

William D. Rubinstein (Melbourne, Australia) writes:

‘I have learned that Alfred Jones was born on 12 July 1812 and baptized at St Stephen Walbrook Church in the City of London, the son of David Jones and Sarah Lydia née Shepard. According to his (almost certain) brother’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, David Jones was a solicitor. I have also now traced Alfred Jones in the 1861 Census, where he was listed as a “solicitor” at Wandsworth Common, living with his two sisters. He was unmarried.’

Gene Gnandt (Houston, TX, USA) wonders whether Alfred Jones was a Justice of the Peace and, if so, whether use of the initials ‘J.P.’ resulted in a mistaken belief that they represented his forenames.

We note that the index on page 313 of Paul Morphy. Skizze aus der Schachwelt by Max Lange (Leipzig, 1881) had ‘P. Jones’.

8925. Awkward squares

From page 219 of The Handbook of Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1965):

‘Most chess difficulties spring from pieces on awkward squares: there is something to be said for keeping to “natural” squares, if one knows which they are!’

8926. Tournament in 1935-36 with 700,000

participants

A report on page 92 of the April 1936 Chess Review:

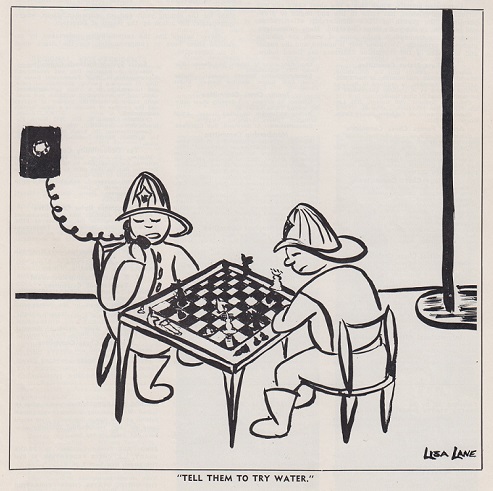

8927. Artwork

Information about sketches, cartoons and other artwork by prominent chess figures is always welcome. From the front cover of Chess Life, 20 April 1961:

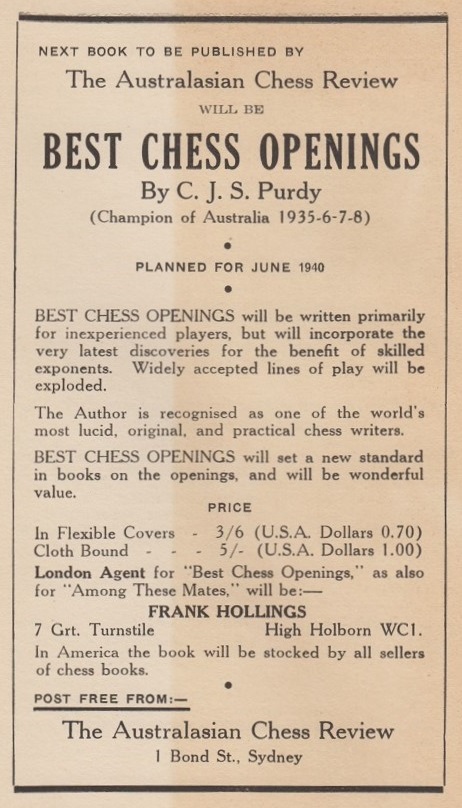

8928. Best Chess Openings

Page 80 of “Among These Mates” by “Chielamangus” (Sydney, 1939) comprised an advertisement for a forthcoming book by C.J.S. Purdy (whose pseudonym was “Chielamangus”) which never came forth:

8929. Eye patch (C.N. 8922)

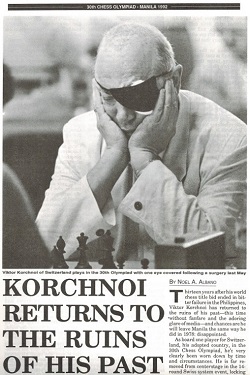

Joose Norri (Helsinki) recalls that pages 1 and 2 of the tenth bulletin of the 1992 Olympiad in Manila had photographs of Victor Korchnoi, who had recently undergone an eye operation in Switzerland. Below is page 1:

8930. Less docility

The first paragraph of an article by the Badmaster, G.H. Diggle, on pages 15-16 of volume two of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1987), reproduced from the February 1985 Newsflash:

‘The chess public seems to be becoming far less docile towards chess literature and the unfortunate Editors, Authors and Publishers who produce it. Indeed, the correspondence columns of CHESS and the BCM have of late shown an increasing “militant tendency” in various quarters of the Realm. In the November CHESS, for example, there “came up from Zummerzet” a letter full of “strong cider” upbraiding the Editor for wasting “the first six pages of the June issue with pointless waffle about the Phillips and Drew tournament when you could have given us six pages of games instead”. (In fact, there were ten pages of games already, and it could be argued that topping up with six more might have reduced the average reader to the plight of the replete youth at the Sunday School Treat who could not manage his last cream bun: “Sorry, Miss, I can still eat but I can’t swaller!”) Equally startling was an earlier letter to the BCM from a canny Scot who clearly expected chess news and not chess history for his “saxpences” and recommended one lengthy article (by none other than the Badmaster!) as “a cure for insomnia”. (The astonished BM proceeded to re-read his own “masterpiece” and soon “dropped off” himself.)’

8931. Sleep

On page 13 of the January 1970 Chess Life &

Review, in an article entitled

‘Do you dream about chess?’

‘Only once. I was ill at the time. I caught a cold after a game with Averbakh in 1959 and in my fever dreamt I saw an enormous rook in front of me. This rook went from QR1 to QB1; it looked huge and terrible. But I have never dreamed up a complete game as Bronstein has done.’

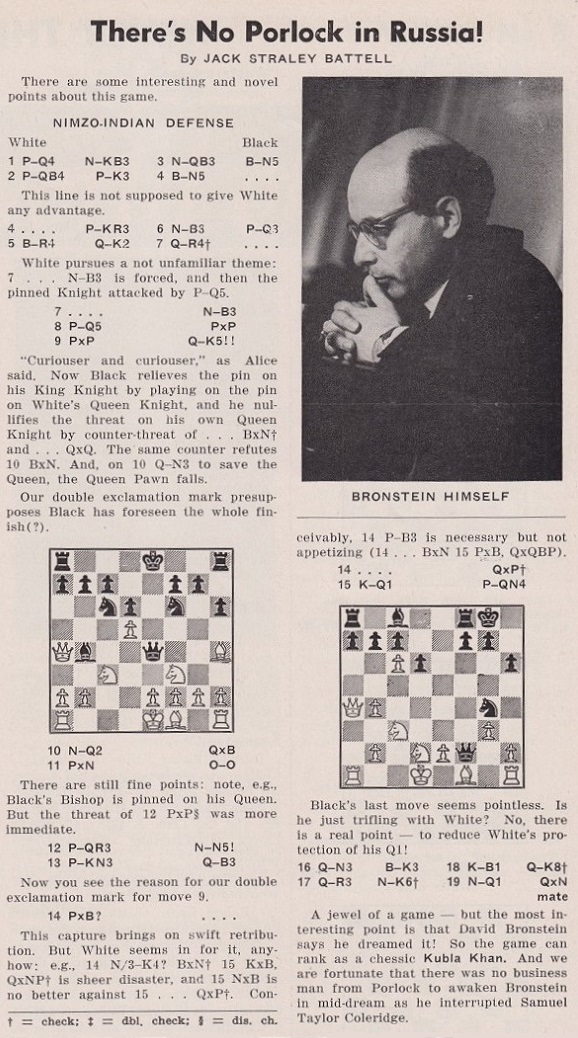

The Bronstein game was published by J.S. Battell on page 225 of the August 1961 Chess Review:

Wanted: more details about the game, which was given as Bronstein v Bronstein, Moscow, 1961 on page 142 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974).

Our latest feature article is Chess and Sleep.

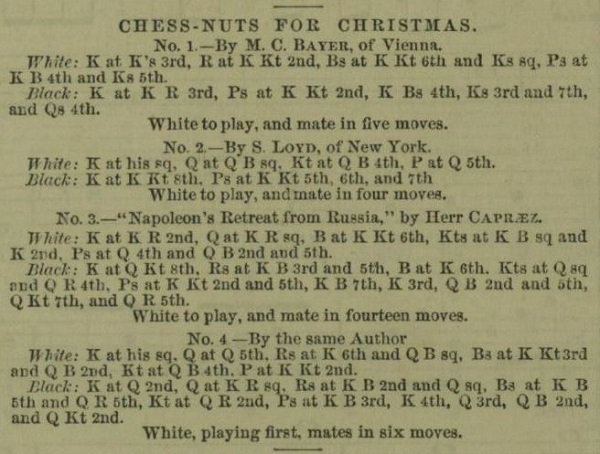

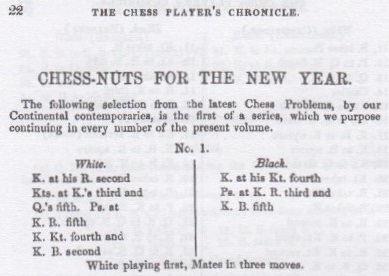

8932. Chess nuts

A footnote on page 206 of America’s Chess Heritage by Walter Korn (New York, 1978):

‘The hilariously double-edged expression “Chess-Nuts” was first employed as the pseudonym of an anonymous “letter-to-the-editor” correspondent of the chess column in the Illustrated London News in the mid-nineteenth century. The column, along with the signature, was later taken over by Howard Staunton. The fitting appellation was most likely coined by Charles Dickens, who was a student of chess. At the time just before the term first appeared in the column, Dickens described some of his analytical and solving efforts as little “Chess Nuts” – as is collaborated by his letters and by biographies about him.’

Not everyone will share Korn’s view as to what engenders hilarity.

He may have been following pages iii-iv of American Chess-Nuts by E.B. Cook, W.R. Henry and C.A. Gilberg (New York, 1868). Page iv stated:

‘According to historical record, the word-play “Chess Nuts” was first used by a correspondent of the Illustrated London News as a signature. Mr Staunton, thereafter, employed “Chess Nuts” as a heading for little collections of positions given in the Chess Player’s Chronicle and Illustrated London News.’

No pseudonymous use of ‘Chess nut’ by a correspondent in the Illustrated London News has yet been found, but one early occurrence of the term in a heading can be shown, from page 610 of the 19 December 1857 issue:

Concerning the above-quoted reference to the Chess Player’s Chronicle, it should be borne in mind that Staunton’s editorship ended in 1854.

Charles Dickens was not mentioned in American Chess-Nuts, but our feature article on him includes this passage from the Dallas Morning News of 21 June 1891, part two, page 16:

What grounds did Walter Korn have for referring to letters and biographies?

8933. The Micawbers of Chess

From pages 110-111 of The Chess Mind by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1951):

‘It often happens that a line of play is too hard to analyse exhaustively within the time at the player’s disposal. He sees a few variations that are definitely in his favour, sees the possibility of one or two clever moves in the distance, sees no immediate refutation and, therefore, adopts the promising line, judging that the continuations will all be satisfactory.

In practice, the judgment that “something favourable will turn up” is true with a frequency that is inversely proportional to the player’s laziness. To the Micawbers of Chess there only happen bad results and occasional pieces of luck when an opponent plays particularly badly.’

8934. Broad sweeps

By definition, broad sweeps are liable to be wide of the mark. Perfectly worded bons mots are not necessarily perfectly true, but whatever the infusion of comic exaggeration, more than a mere kernel of truth is needed.

These intangibilities may be relevant to a remark by Gerald Abrahams on page 178 of Teach Yourself Chess (London, 1948). It is the first sentence of Part III (‘Chess Learning’), Chapter V (‘The Ground Work of the Openings’):

‘The history of the development of Chess is the history of development in Chess.’

Some may feel that this is a clever thought, cleverly phrased; others that the kernel of truth is all but undetectable. For our part, we continue to cite such snippets neutrally, leaving readers to make of them what they will.

In case it helps, below is the full page:

8935. Magnus Carlsen’s early chess reading

From page 16 of Wonderboy by Simen Agdestein (Alkmaar, 2004):

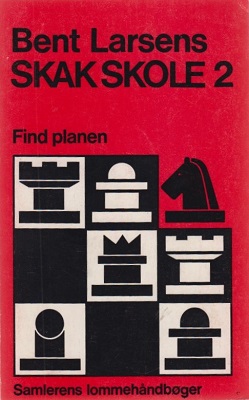

‘Magnus impressed in this Gausdal tournament [in 2000] even if he had just been actively playing tournament chess for half a year. The previous autumn Magnus and his father had sat and read Bent Larsen’s “Find the Plan”, one of the many good books written by the old Danish world-beater. The book consists of lots of diagrams that pose the task: Find the plan! Simple and effective.

At Gausdal it was obvious that Magnus knew a bit about the opening. His father had some old chess biographies lying around, and Magnus had “thumbed through” them. His first opening book was “The Complete Dragon” by grandmaster Eduard Gufeld [and Oleg Stetsko], a comprehensive work in English reckoned more for grandmasters than small boys who had just learned how to play.’

In the 2013 edition, this passage (stylistically unimproved) is on page 20.

Page 19 of the Italian translation (Rome, 2006) of Agdestein’s original book suggested clearly that the Larsen book was in English (‘L’autunno precedente insiema [insieme] a suo padre aveva letto il libro di Bent Larsen Find the Plan ...’), but no such book exists. Larsen’s work was published in Danish as volume two in his series of four booklets, Bent Larsens Skak Skole, the title being Find planen (Samlerens Forlag, Copenhagen, 1975):

We also have the Swedish translation, Du måste ha en plan (Stockholm, 1977). The four parts of the Skak Skole series were brought together in an English edition entitled Bent Larsen’s Good Move Guide (Oxford, 1982).

The English book, in turn, was translated into French as Les coups de maître aux échecs (Paris, 1989).

8936. Chess nuts (C.N. 8932)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) notes that the term ‘chess-nuts’ is on page 22 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1850:

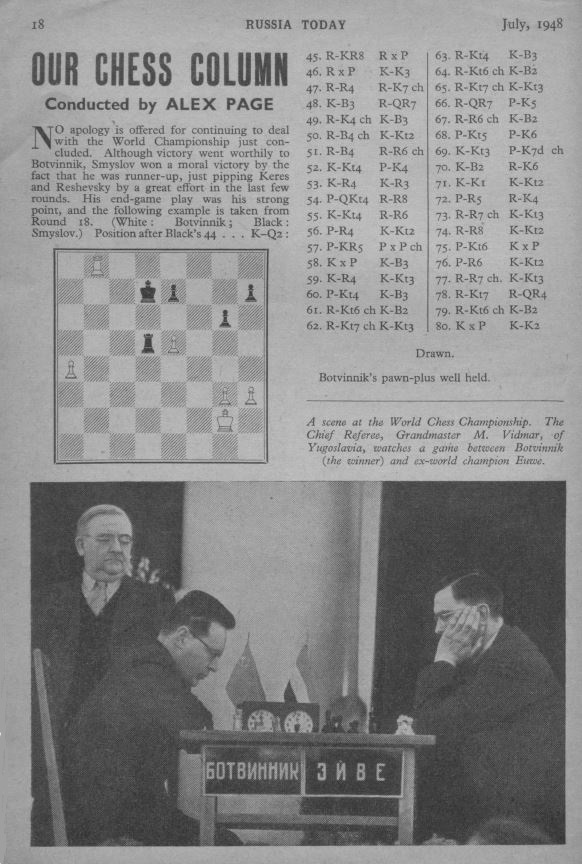

8937. Russia Today

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has forwarded a chess column by Alex Page in Russia Today, July 1948, page 18:

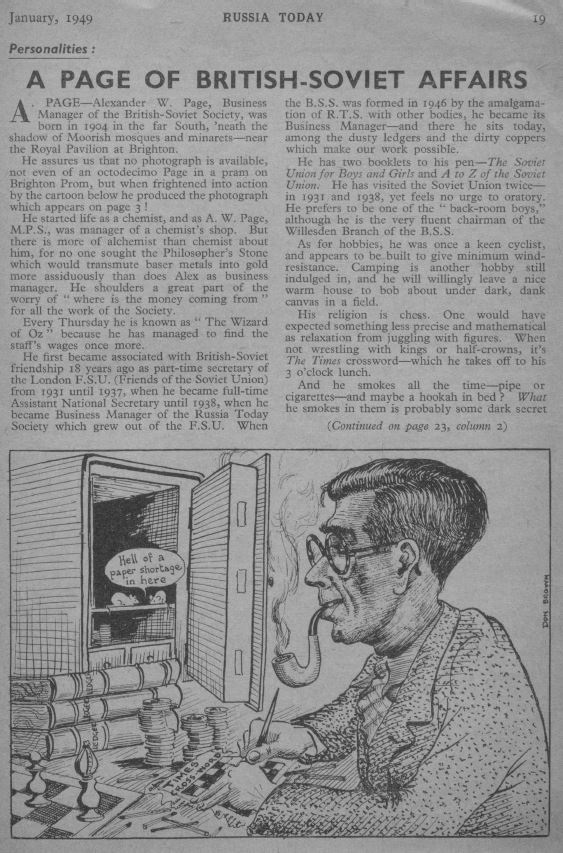

Page 3 of the January 1949 issue of Russia Today, a publication of the British-Soviet Society, had a photograph of Alexander W. Page with Reginald Bishop:

The article about Page in the same issue:

8938. Tal in Stockholm

Mr Urcan has also submitted a photograph published on page 95 of the Illustrated London News, 21 January 1961:

8939. Skak

Skole (C.N. 8935)

Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark) notes that although only volumes 1-4 of Skak Skole were included in the English and French compilations of Bent Larsen’s booklets, there were further Danish volumes. The series (1975-85) was:

1. Find kombinationen (Find the combination)

2. Find planen (Find the plan)

3. Find mestertrækkene (Find the master moves)

4. Praktiske slutspil (Practical endgames)

5. Solide åbninger (Solid openings)

6. Skarpe åbninger (Sharp openings)

7. Flere mestertræk (Further master moves).

The back cover of the first booklet (Copenhagen, 1975):

Mr Skjoldager adds that volumes 1-6 have been translated into Norwegian.

8940. Carlsen and silhouettes

A new book about the world champion is Magnus Carlsen Nappulasta kuninkaaksi by H. Torkkola (Helsinki, 2014):

The front cover has prompted us to produce a feature article, Chess and Silhouettes.

8941. Tartakower on Prague, 1931

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) notes a wide-ranging

article by Tartakower on pages 209-215 of the August 1931

Magyar Sakkvilág:

8942. Tells

of

‘Tells of’ is a formulation favoured by writers unconcerned with specifics. From page 133 of The Complete Chess Addict by M. Fox and R. James (London, 1987):

‘B.H. Wood tells of this débâcle in a postal tournament. After 1 e4, Black replied: “...b6 2 Any, Bb7.” Now “any” is a useful postal chess time-saver; it’s shorthand for “any move you care to make”. So White replied with the diabolical “2 Ba6 Bb7 3 Bxb7” (and wins the rook as well).’

Where Wood told of this is not mentioned. We recall, though, that on page 279 of the June 1961 CHESS he reported that another magazine had told of a king’s-side version:

‘Chess Review tells of a postal chess player who rather recklessly wrote his White opponent thus: “Whatever you play, my first two moves are 1...P-KN3 and 2...B-N2.”

No prizes for guessing White’s first three moves.’

However, what Chess Review (April 1961, page 102) had told of contained no ‘Whatever you play ...’ remark and was merely a gleaning from an unspecified issue of another magazine:

‘We appreciatively take this item from the Ohio Chess Bulletin, which describes the “if” moves offered by an impatient player of the black pieces: “In the game in which you will play White, my first two moves as Black will be: 1...P-KN3, 2...B-N2.” Improbable as it may seem at first glance, White can now immediately apply the crusher. Do you see how he wins two pieces?’

Can a reader trace the relevant issue of the Ohio Chess Bulletin or quote other early versions of the story? Some later writers recounted it with details which may or may not have been invented; see, for example, page 66 of Playing Chess by Robert G. Wade (London, 1974).

8943. Firefighting (C.N. 8927)

Further to the above cartoon by Lisa Lane on the front cover of Chess Life, 20 April 1961, we add one from page 119 of A History of Chess by Jerzy Giżycki (London, 1972):

When was the cartoon by Zbigniew Lengren first published?

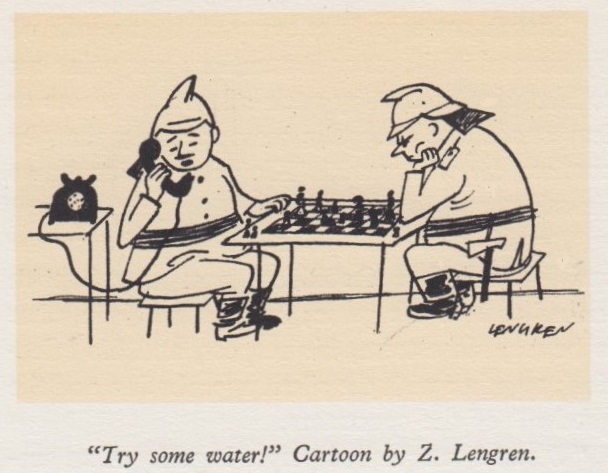

8944.

Fischer book by Luis Matos

An addition to Books

about

Fischer and Kasparov has been received from Juan

Carlos Sanz Menéndez (Madrid): Fischer sus 200 mejores

by Luis Matos. It comprises 101 pages and has 200 games,

the last being the 21st game in the 1972 match against

Spassky (the book’s only coverage of that contest). A

brief biography is included, and some notes are taken from

Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games. It has a mixture

of the Spanish descriptive notation and the algebraic

notation. There are no publication details, but our

correspondent believes that the book appeared in

Venezuela, where Matos was active (writing chess columns

for the newspaper Universal in Caracas, as well as

articles under the pseudonym ‘Jaque Matos’). The

front-cover photograph of Fischer is a reverse shot.

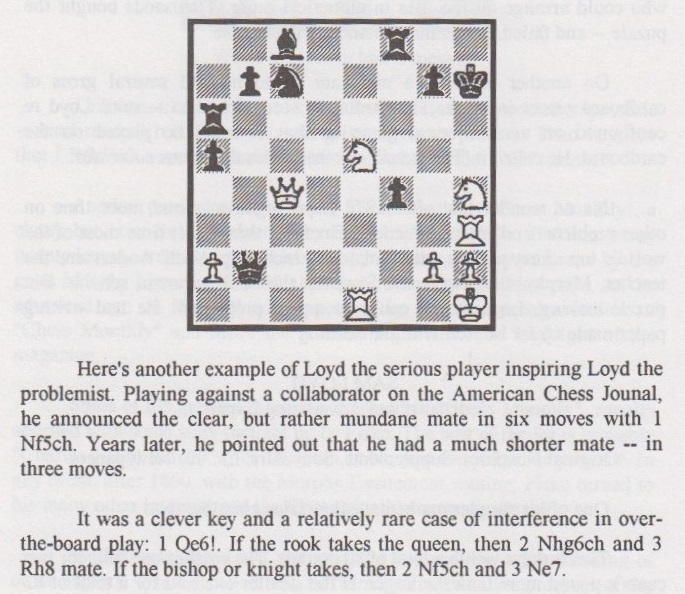

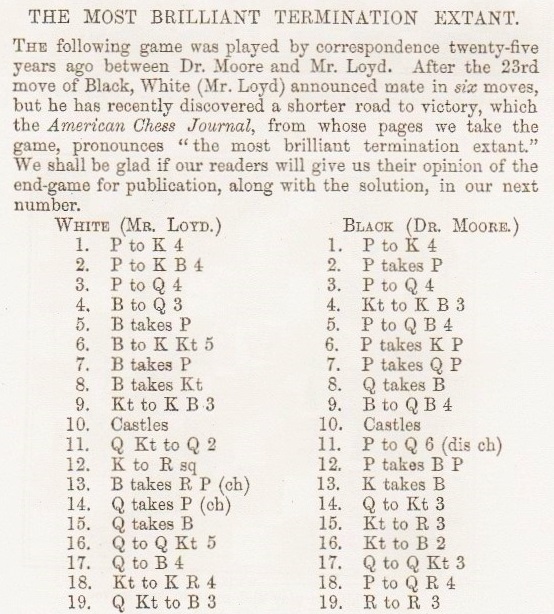

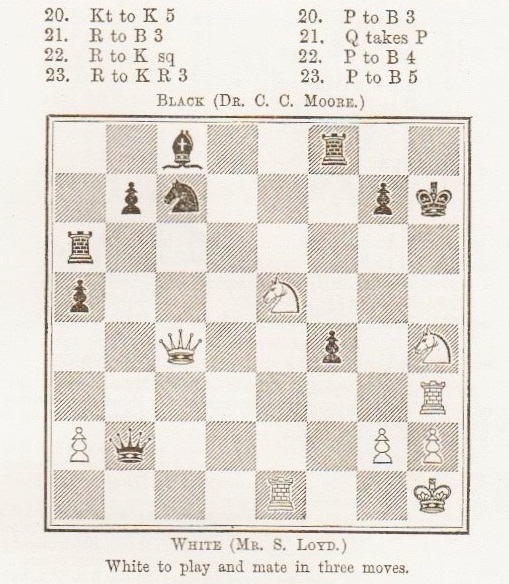

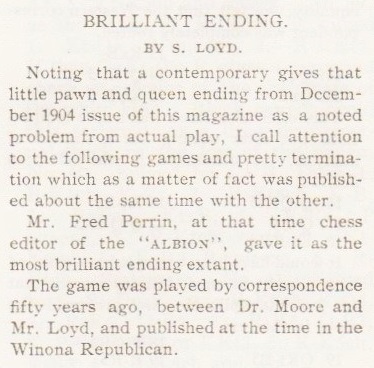

8945. ‘The most brilliant termination extant’

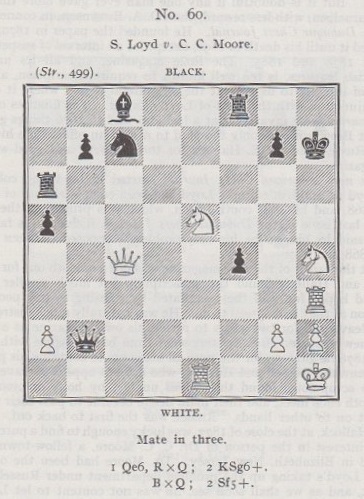

White can mate in three with 1 Qe6.

From Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

‘Concerning diagram 60 in Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems, the famous Loyd v Moore game has always struck me as suspicious. The mate in three, showing (in the problemist’s jargon) a Nowotny followed by matching battery shut-offs, seems just too perfect to have arisen by chance. I recall, though, that the game-score is in one of Wenman’s books.’

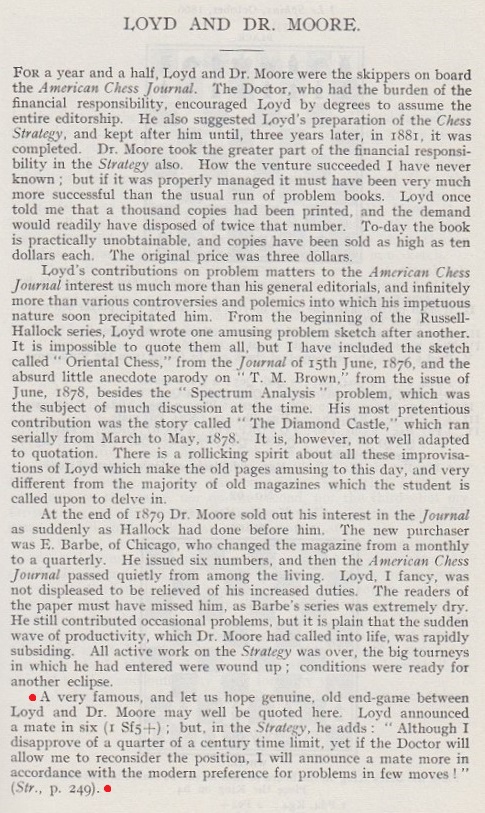

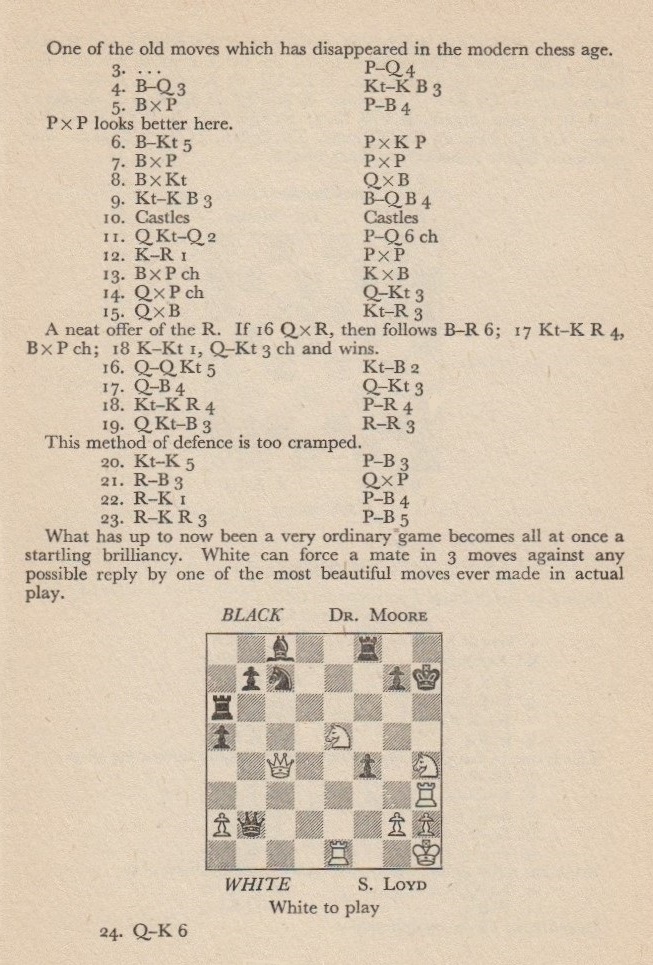

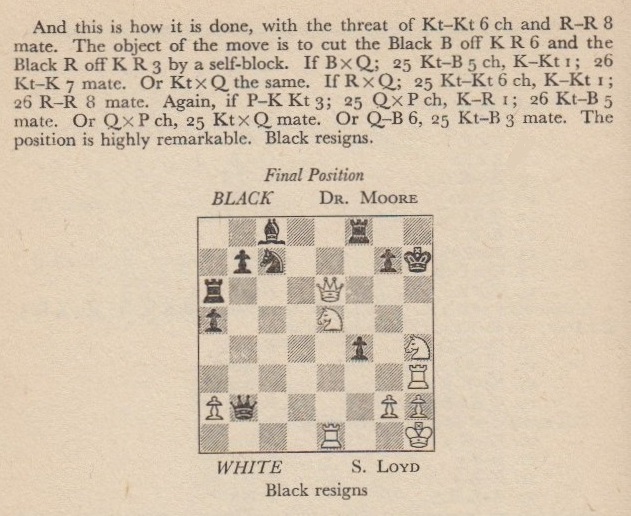

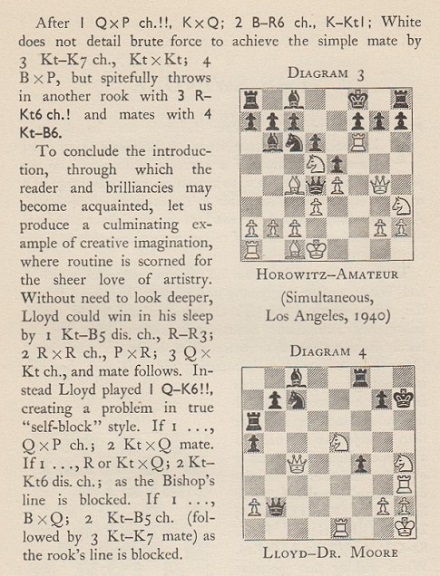

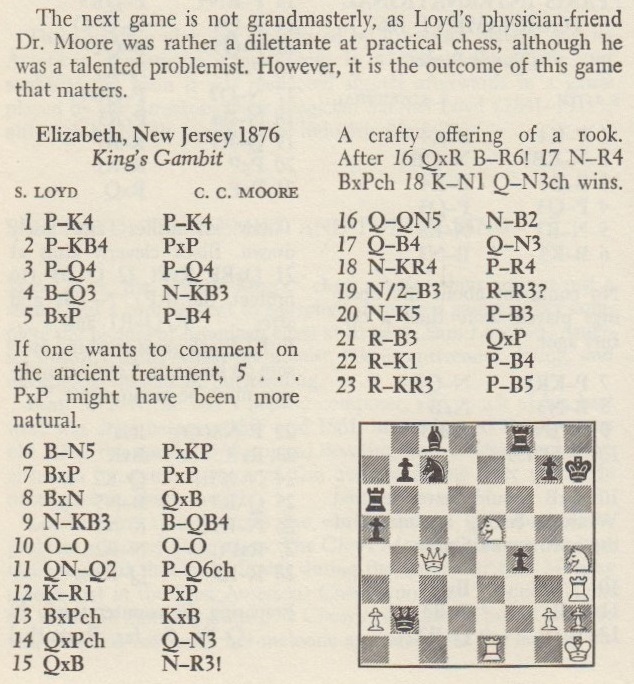

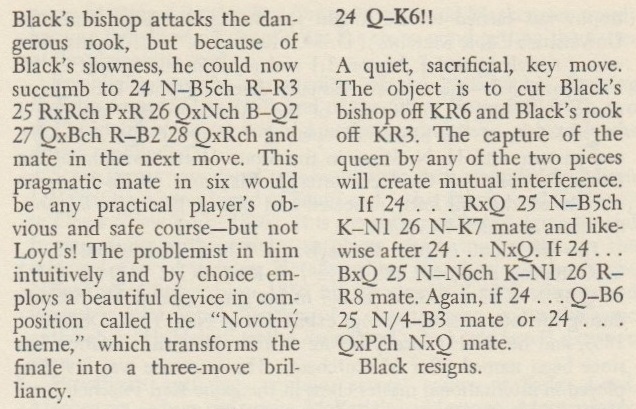

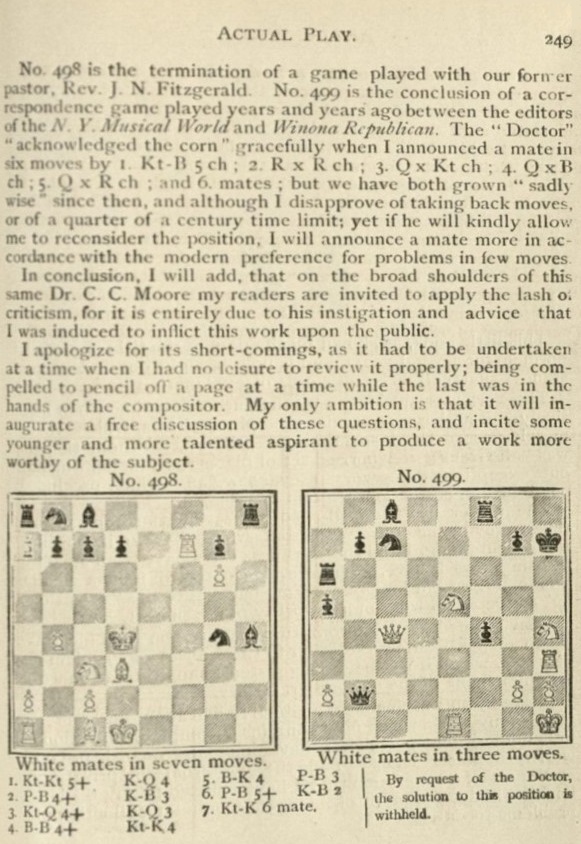

It is a tangled affair, and we begin by showing pages 56-57 of Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems by Alain C. White (Leeds, 1913):

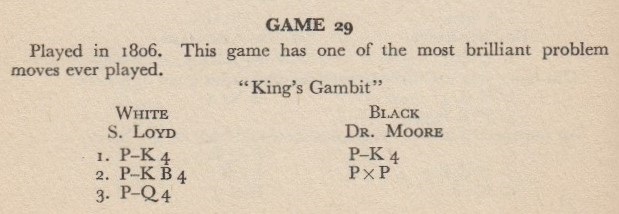

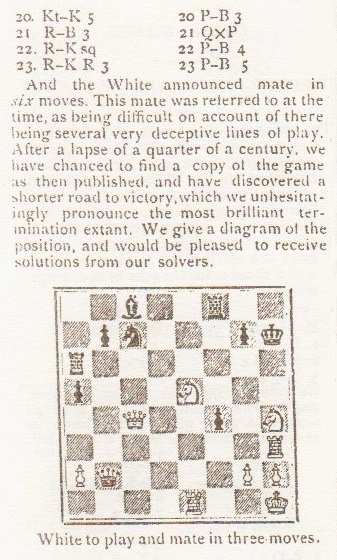

As regards Wenman, the following comes from his book One Hundred and Seventy Five Chess Brilliancies (London, 1947), the pages being unnumbered:

Wenman’s date for the game, 1806, was 35 years before Loyd was born.

Another author who discussed the game, though naming White as ‘Lloyd’, was Walter Korn, on page 3 of The Brilliant Touch (London, 1950):

Korn published the full score (‘Elizabeth, New Jersey, 1876’), with White named as Loyd, on pages 44-45 of America’s Chess Heritage (New York, 1978):

The game is also in databases, with various years from 1853 to 1906. In the May 1942 BCM, page 100, T.R. Dawson gave the finish with a diagram labelled ‘c. 1868’.

On page 10 of Sam Loyd His Story and Best Problems (Dallas, 1995) Andrew Soltis steered clear of specifics, except for the name of a nineteenth-century magazine, which he nearly spelt correctly:

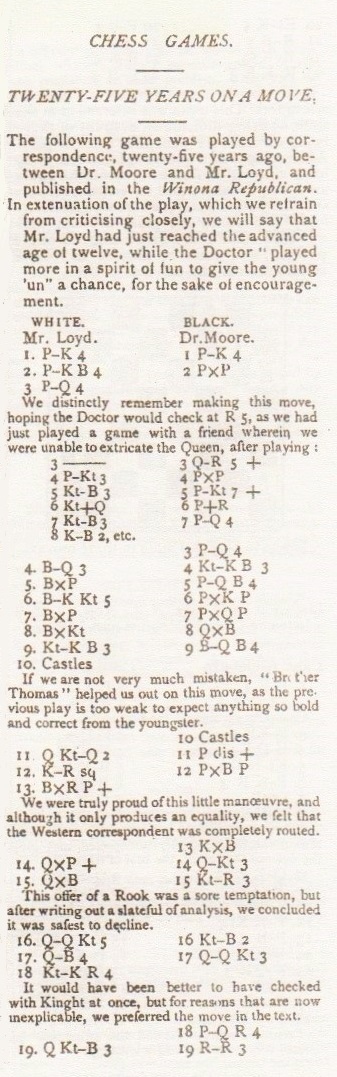

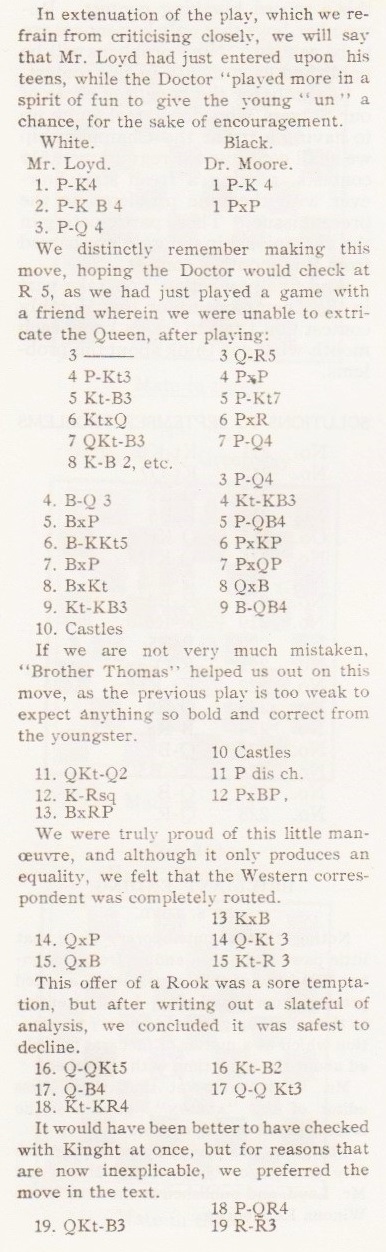

Below is the full game’s appearance on pages 194-193 [sic

– the numbering of the two pages was inverted] of the

November 1878 American Chess Journal:

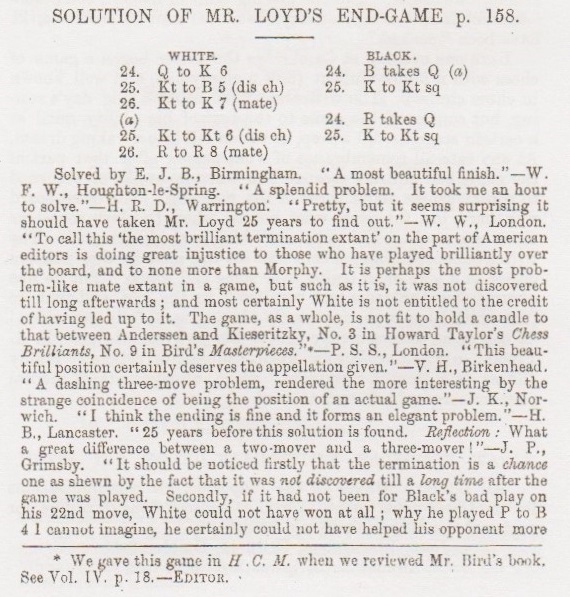

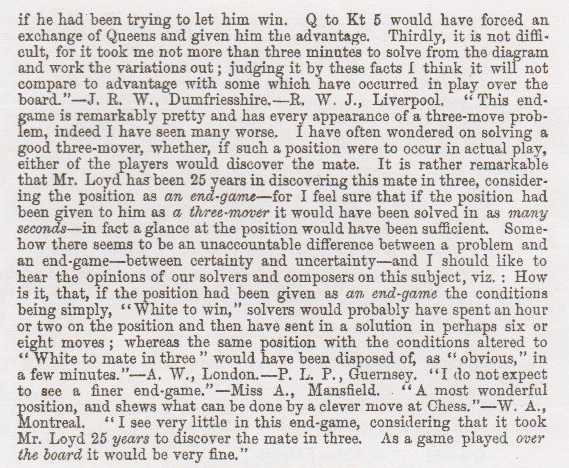

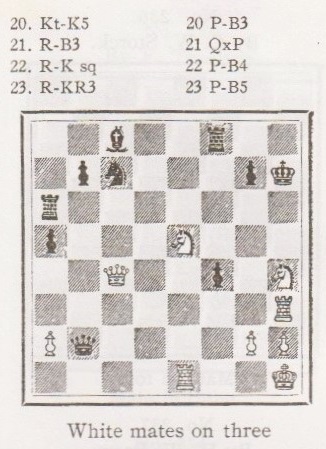

The game was subsequently published (headed with the American Chess Journal’s description ‘The most brilliant termination extant’) on pages 157-158 of the March 1879 Huddersfield College Magazine:

The opinions solicited by the magazine were presented on pages 221-222 of the May 1879 issue:

Loyd himself gave only the conclusion on page 249 of his book Chess Strategy (Elizabeth, 1878). The scan below has been provided by the Cleveland Public Library:

Loyd presented the full game on pages 45-46 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, November 1905, and left readers to assume that he did indeed play 24 Qe6:

For the pawn and queen ending referred to in Loyd’s first paragraph, see C.N. 8692.

As regards Moore, a brief article and illustration by Loyd were published on page 1342 of the Scientific American Supplement, 11 August 1877:

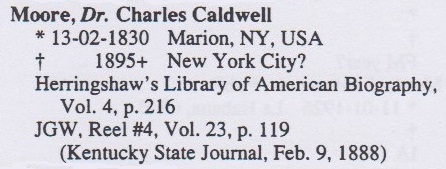

Moore’s entry in Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige (Jefferson, 1987) was slightly augmented in the unpublished 1994 edition:

The earliest publication of the Loyd v Moore game or position found so far dates from 1878. Is it possible to trace earlier appearances and, in particular, to corroborate Loyd’s claim that he played the game by correspondence when he was a boy and that it was published in the Winona Republican around 1853-54?

8946. Bronstein v Bronstein (C.N. 8931)

Roland Kensdale (Aberdeen, Scotland) quotes from page 109 of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice by D. Bronstein and T. Fürstenberg (London, 1995) and page 117 of the revised edition (Alkmaar, 2009). A game between Bronstein and Boleslavsky, Moscow, 1950 began 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Nf3 d6 5 Qb3, and at this point Bronstein wrote:

‘Many years ago, I think in 1960, during the Soviet Championship in Leningrad, I was thinking about my opening in the next game with Korchnoi. As he often played 1 c4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nc3 I decided to try 3...Bb4 and if 4 d4 then 4...d6. Then, using my fantasy, I was dreaming of a nice combination after 5 Bg5 h6 6 Bh4 Qe7! 7 Qa4+? Nc6 8 d5 exd5 9 cxd5 Qe4 10 Nd2 Qxh4 11 dxc6 O-O 12 a3 Ng4 13 g3 Qf6 14 axb4 Qxf2+ 15 Kd1 b5 16 Qb3 Be6 17 Qa3 Ne3+ 18 Kc1 Qe1+ 19 Nd1 Qxd1 mate.

After the tournament I gave a lecture in the Chigorin Chess Club and told the audience about this and used the expression “chess dream”. Later I read in a book that I saw this variation during my sleep!’

8947. An exceptionally difficult quiz question

‘After his blindfold displays he would drink brandy in ordinary tumblerfuls.’

Who wrote that about Alekhine?

| First column | << previous | Archives [124] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.