Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [147] | next >> | Current column |

10137. The Pirc Opening

A note after 1 e4 d6 2 d4 Nf6 in the game Richard G. Ely v Gregory Koshnitsky, Melbourne, 1956-57, on page 92 of Chess World, April 1957:

‘This is the Pirc (pronounce Peerts as in vision of Peerts plowman). It is an old defence, formerly known in England as the Toad-in-the-Hole.’

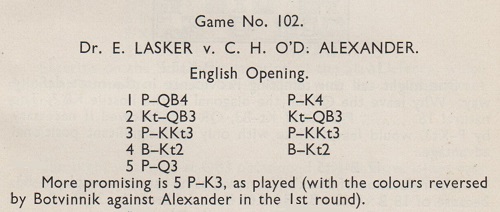

10138. Games with the same opening

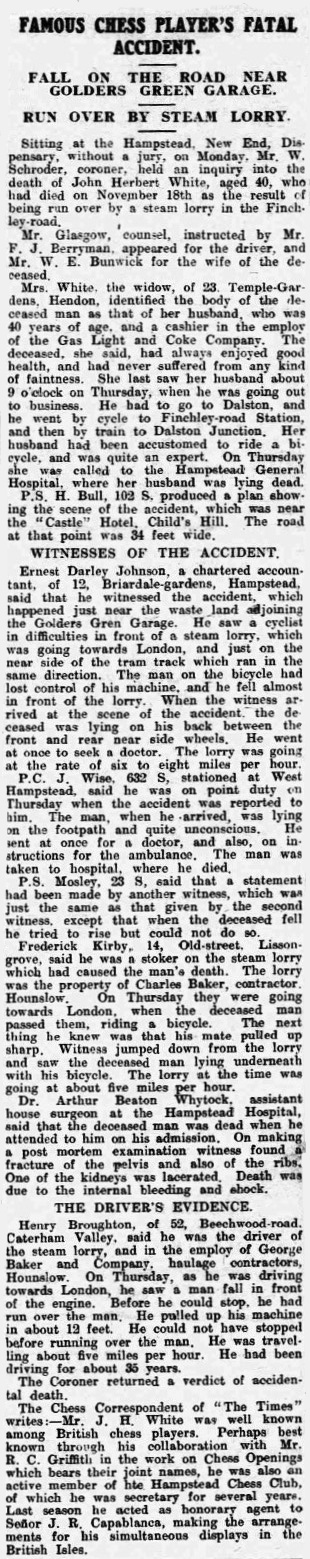

Page 118 of the May 1957 Chess World discussed a game between L. Awdiew and Peter Kalinovsky, Melbourne, 1956-57 which began 1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Nf3 Bf5 5 Qb3 Qb6 6 Qxb6 axb6 7 cxd5 Nxd5 8 Nxd5 cxd5 9 e3 Nc6 10 Bd2 e6 11 Bb5 Bd6 12 O-O Ke7 13 Rfc1 Rhc8 14 Ne1 Rc7

15 Nd3. ‘What did Black do now? Answer on page 124.’

As mentioned on page 124, the answer had already been published (‘prematurely’) on page 104 of the April 1957 issue: after 15 Nd3, ‘Black simply won a piece. If you haven’t seen it yet, you soon will’.

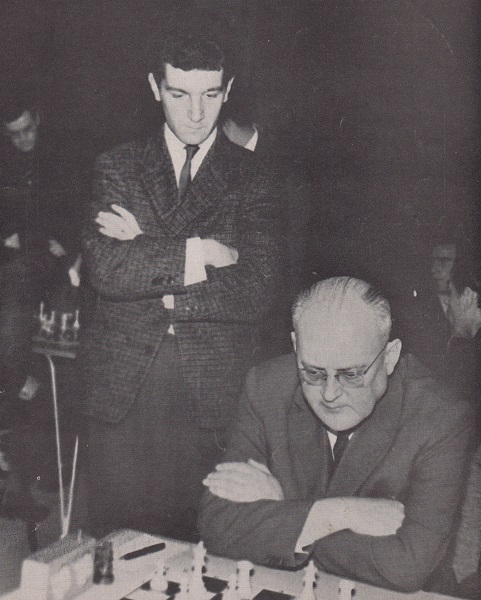

Page 118 pointed out that the position after 10 Bd2 had occurred in a Capablanca game (his famous victory as Black against Janowsky, New York, 1916), and we show Irving Chernev’s note on page 304 of The Golden Dozen (Oxford, 1976):

The ever-fallible FatBase

database had three versions of the 1916 game, one

played in New York (4...Bg4), one played in New Delhi

(4...Bf5) and one played in New York (4...Bf5) with

Janowsky (White) named as the winner.

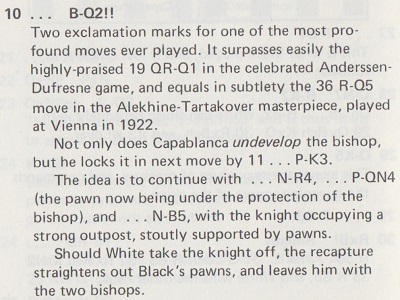

Databases show a number of games which reached the position after 10 Bd2, the only pre-1916 instance being Swiderski v Marshall, Hanover, 8 August 1902. From page 111 of the tournament book:

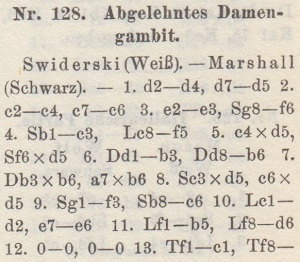

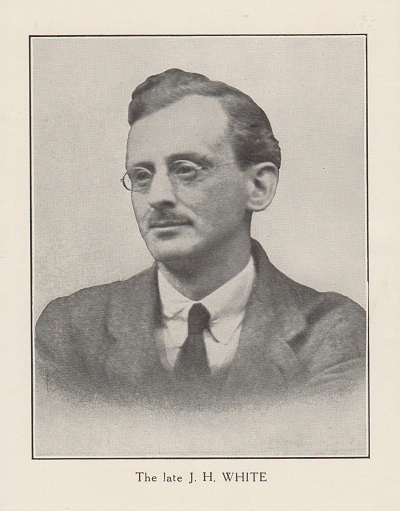

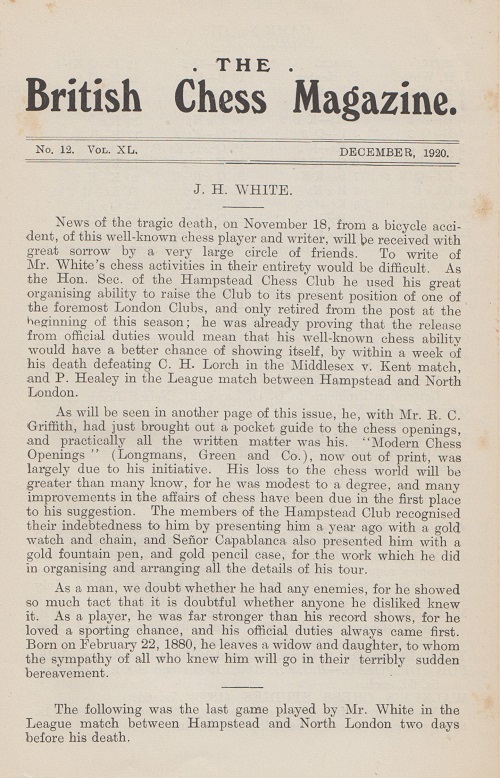

10139. John Herbert White (1880-1920)

Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) sends this report from page 3 of the Hendon and Finchley Times, 26 November 1920:

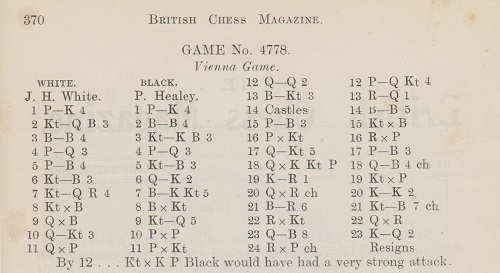

Below is the coverage of White’s death in the December 1920 BCM (frontispiece and pages 369-370):

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Bc5 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 d3 d6 5 f4 Nc6 6 Nf3 Qe7 7 Na4 Bg4 8 Nxc5 Bxf3 9 Qxf3 Nd4 10 Qg3 exf4 11 Qxf4 dxc5 12 Qd2 b5 13 Bb3 Rd8 14 O-O c4 15 c3 Nxb3 16 axb3 Rxd3 17 Qg5 c6 18 Qxg7 Qc5+ 19 Kh1 Nxe4 20 Qxh8+ Ke7 21 Bh6 Nf2+ 22 Rxf2 Qxf2 23 Qf8+ Kd7 24 Rxa7+ Resigns.

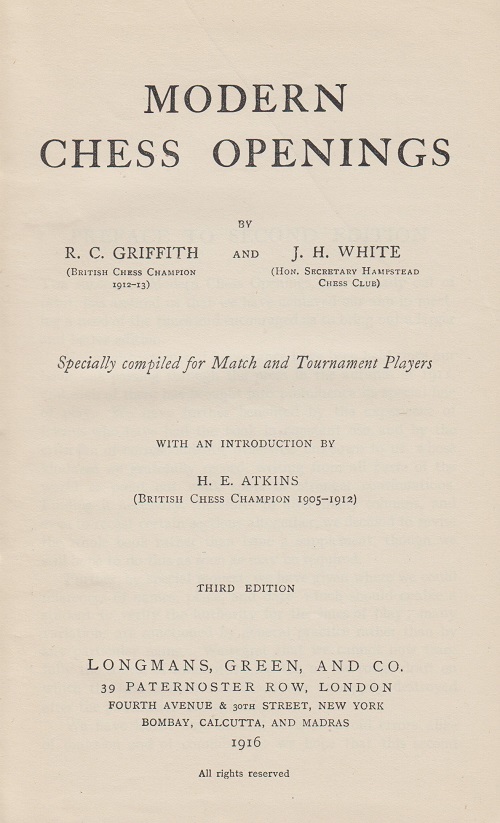

J.H. White co-edited with R.C. Griffith the first three editions of Modern Chess Openings.

The Preface to the fourth edition, by Griffith and M.E. Goldstein (London, 1925), began:

‘The tragic accident to Mr J.H. White in the latter part of 1920 deprived the chess world of a brilliant player and writer, who did so much in bringing Modern Chess Openings into being.’

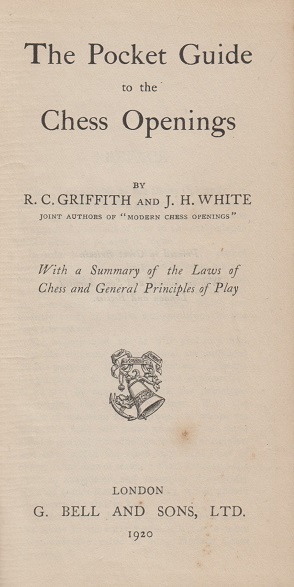

Page 388 of the December 1920 BCM carried a highly positive review by J.H. Blake of another work co-written by Griffith and White, The Pocket Guide to the Chess Openings (London, 1920):

10140. An offer on eBay

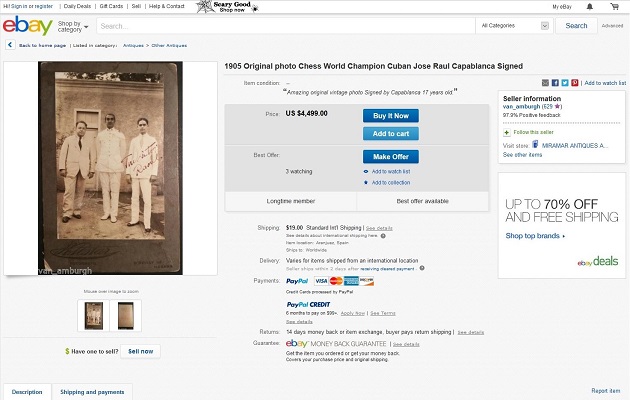

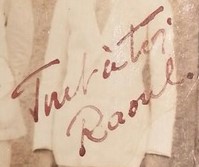

It is naturally not our practice, as a matter of principle, to reproduce eBay items, but Gianluca Cremasco (Verona, Italy) draws attention to this offer (asking price: $4,499) from Aranjuez, Spain:

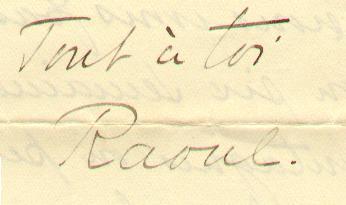

The individual on the right bears little resemblance to Capablanca. Concerning the signature, readers may draw their own conclusions after comparing it with what can be found in a 1935 letter which we own, written by Capablanca to his future wife and shown in The Genius and the Princess:

10141. FIDE decision

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) notes a decision by FIDE at its General Assembly in Baku on 13-16 September 2016:

‘GA-2016/50. To announce the year of 2018 as the year of E. Lasker.’

Pro memoria, 2018 will be the 150th anniversary of Emanuel Lasker’s birth.

10142. Modern Chess Openings (C.N. 10139)

In 1952 Walter Korn brought out the eighth edition of Modern Chess Openings. A year or two later, bizarrely, a company in Göteborg published a Swedish translation of the fifth edition, which had been written back in 1932, by P.W. Sergeant, R.C. Griffith and M.E. Goldstein. The Swedish book had 1954 on the dust-jacket and 1953 on the title page and imprint page.

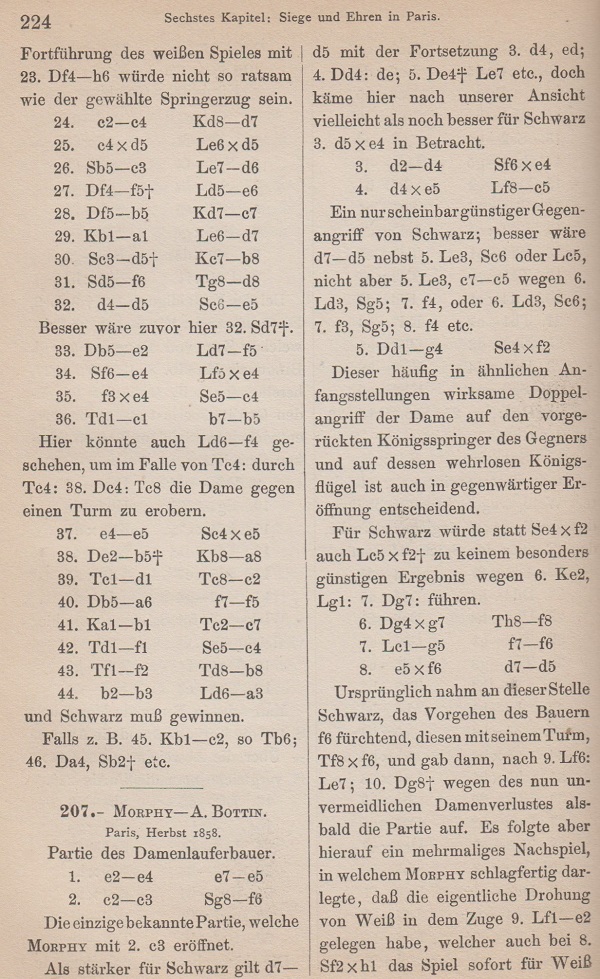

10143. Morphy v Bottin

Han Bükülmez (Ecublens, Switzerland) asks for information about a Morphy gamelet against A. Bottin (Paris, 1858): 1 e4 e5 2 c3 Nf6 3 d4 Nxe4 4 dxe5 Bc5 5 Qg4 Nxf2 6 Qxg7 Rf8 7 Bg5 f6 8 exf6 Rxf6 9 Bxf6 Be7 10 Qg8+ Resigns. Our correspondent adds that a longer score is also readily found, comprising post-game analysis said to have involved Morphy.

There are brief accounts in the Morphy collections by G. Maróczy and P.W. Sergeant, but the most extensive coverage of the game that we recall is on pages 224-225 of Paul Morphy Sein Leben und Schaffen by Max Lange (Leipzig, 1894):

What more can be discovered about Morphy v Bottin?

10144. Net Film

A large amount of Russian-language footage from the 1950s to the 1990s can be viewed by searching with the word ‘chess’ at the Net Film website.

10145. Emery Gondor (C.N. 8457)

On-line at the Center for Jewish History is a complete book, dated 1922, of Emery Gondor’s sketches of chessplayers.

10146. A mysterious composition (C.N.s 145, 187 & 2705)

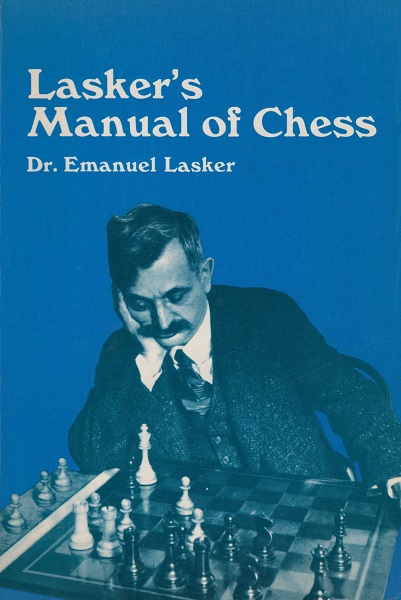

The Center for Jewish History also has a fine photograph of Emanuel Lasker (Los Angeles Athletic Club, 31 March 1926).

In C.N. 145 Michael McDowell noted the photograph’s appearance, in reverse form, in the Dover re-issue of Alekhine’s book on New York, 1924. In C.N. 187 another correspondent, Michael Squires, mentioned that the reversed version was also on the cover of the Dover edition of Lasker’s Manual of Chess. (See page 178 of Chess Explorations.) Subsequently, Dover corrected the picture:

The solution given in C.N. 145 was 1 Rg8 Rxg8 2 Rh8 Rxh8 3 g7 Rg8 (or 3...Rf8) 4 h7 and wins, but C.N. 2705 (see page 365 of A Chess Omnibus) reported that our computer check with the Fritz program had yielded a humdrum mate in five (i.e. one move faster): 1 Rf7 Rg8 2 Rhg7 (Or 2 g7.) 2...Rh8 3 h7 any 4 Rg8+ Rxg8 5 hxg8(Q) mate.

Nothing has yet been ascertained about the identity of the composer or the source of the problem.

10147. Picture-tampering (C.N.s 3757 & 3901)

The photograph of Capablanca shown in C.N.s 3757 and 3901 occupied a full page (23) in Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929) and was also on page 19 of the third and final issue of Chess Pie, published in 1936:

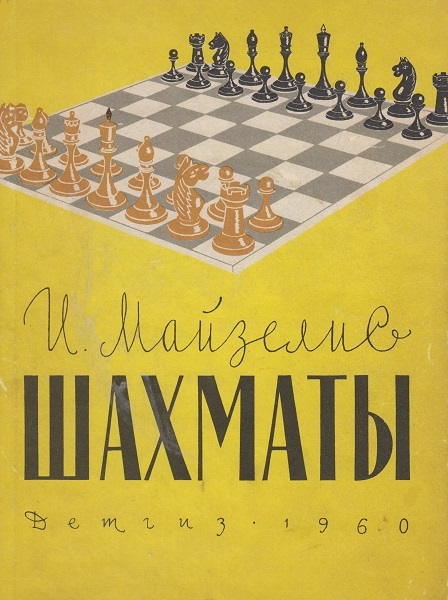

From page 343 of Shakhmaty by I.L. Maizelis (Moscow, 1960):

Well-known portraits of Philidor (page 295), Anderssen (page 304) and Steinitz (page 318) were also tampered with, in the Soviet manner, but why?

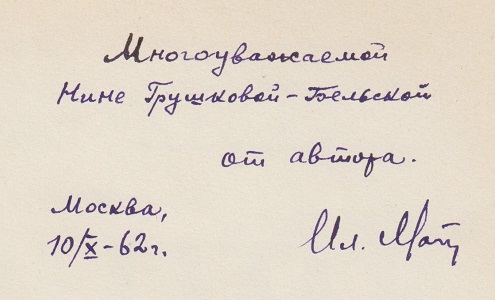

Our copy of Maizelis’ book was inscribed to Nina Hrušková-Bělská:

10148. The feminine touch in chess

Pages 9-10 of the Listener, 7 July 1960 reproduced, under the title ‘The Feminine Touch in Chess’, some observations by Elaine Pritchard in a radio talk on the BBC’s Network Three. A few extracts:

- ‘Most chess clubs are rather like barracks: they lack the feminine touch. We woman players are few, slightly despised, and even sometimes unpopular.’

- ‘The Russians have won every world championship since the title became vacant at the death of Vera Menchik. Yet one feels that the disparity between these champions and some of our own women players is not so great; certainly not so great as between Menchik and any of her challengers.’

- ‘What is the reason for the failure of women to reach

the top class? To begin with, few of us have learned to

play; a mere handful by comparison with men. I am no

mathematician, but relatively speaking I would have

thought our results were reasonable. ... In Russia, far

more women play, and consequently more of them play

better. We may lack imagination, and those of us who do

not, tend to have too much of it; we get out of control

and become wretchedly unsound. We are not always

logical, and our positional play may lack depth. Women

are not long-range planners in life, but rather deal

with the practical and immediate. We usually lack the

will to study, especially endgame play, and rely on

intuition to see us through. We would rather trot out

the faithful old openings we learned years ago than

experiment with new ones. We may lack concentration and

physical stamina for serious tournament play and tire

more easily than men.

Vera Menchik, in contrast, had the perfect temperament, a natural ability furthered by study and a fine positional sense. She was sound rather than imaginative in her play. Although she appeared completely absorbed in chess, her life was not entirely devoted to the game. She had a great sense of fun, was a fine bridge player, and had a keen appreciation of the arts.’

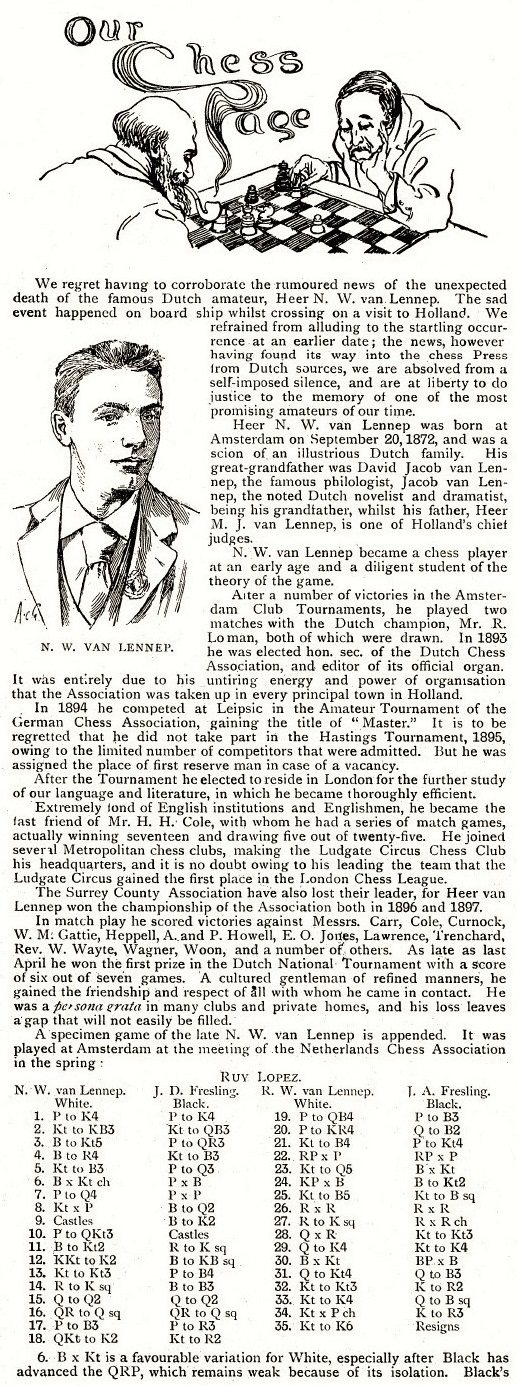

10149. Norman van Lennep (C.N.s 10100, 10106 & 10115)

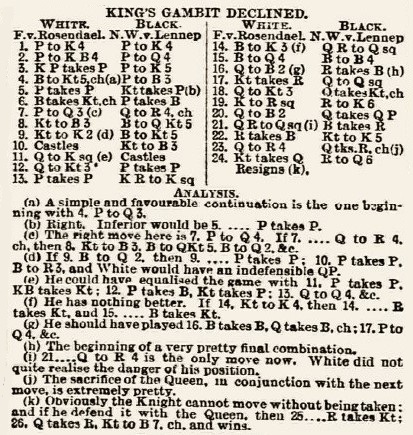

Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) submits a victory against F. v. Rosendael from page 6 of the Standard, 2 July 1895 (which described it as ‘a brilliant little game won at Amsterdam by N.W. v. Lennep, the talented Dutch amateur’):

1 e4 e5 2 f4 d5 3 exd5 e4 4 Bb5+ c6 5 dxc6 Nxc6 6 Bxc6+ bxc6 7 d3 Qa5+ 8 Nc3 Bb4 9 Ne2 Bg4 10 O-O Nf6 11 Qe1 O-O 12 Qg3 exd3 13 cxd3 Rfe8 14 Be3 Rad8 15 Bd4 Bc5 16 Qf2

16...Rxd4 17 Nxd4 Qd8 18 Qg3 Qxd4+ 19 Kh1 Re3 20 Qf2 Qxd3 21 Rad1 Bxd1 22 Rxd1

22...Ne4 23 Qh4 Qxd1+ 24 Nxd1 Rd3 25 White resigns.

Our correspondent has also forwarded the chess column on page 24 of the Westminster Budget, 17 December 1897:

In the above (familiar) game, Black was Tresling, not Fresling.

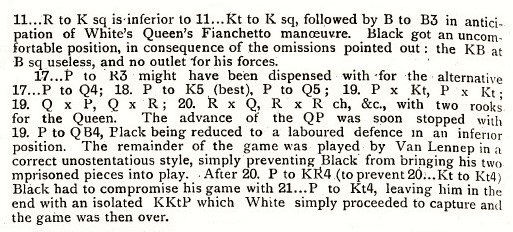

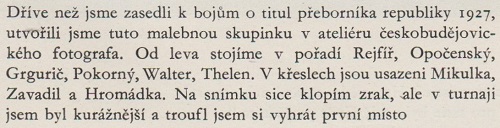

10150. České Budějovice, 1927

From the plate section of the book mentioned in C.N. 10117, Nad šachovnicemi celého světa by K. Opočenský and V. Houška (Prague, 1960):

10151. Alekhine in Buenos Aires (C.N.s 10109 & 10113)

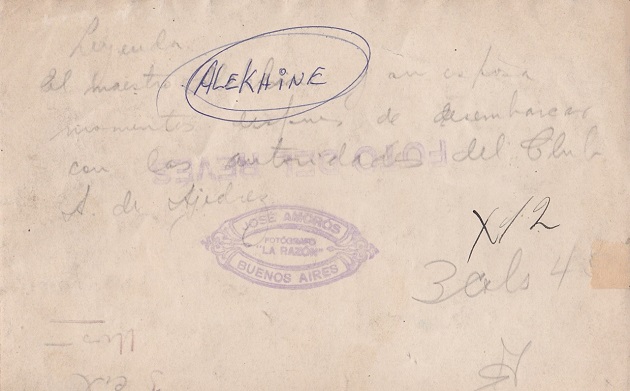

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) and Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) note that the wording on the reverse of the photograph is:

‘Leyenda

‘El maestro Alekhine y su esposa momentos después de desembarcar con las autoridades del Club A. [Argentino] de Ajedrez.’

It is also indicated that the photographer was José Amorós, for La Razón. Did the picture appear in that publication?

Finally, the following words are stamped upside down: ‘Foto del revés’ (‘reversed photograph’).

10152. An Alekhine quip (C.N. 5044)

The full alleged sentence in French appeared on page 91 of Chess World, 1 May 1946:

‘In French the piece we call the bishop is called “le fou” (the fool).

A Lisbon player who had just lost a game was explaining volubly how he should have won because he had the bishops. Alekhine was looking on. He said:

“Deux fous gagnent toujours – mais trois fous, non.”

(Two fools always win, but not three.)’

10153. The greats

From page 147 of Chess World, 1 August 1946:

‘When Capablanca died, and when Lasker died, and when Alekhine died, something of every true chessplayer died, and our special memorial numbers were designed to re-incarnate these great masters in the minds of our readers. From our articles, many players now know Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine better than they ever knew them while they lived.

In chess, very much more than in other sports, great players are a very part of the game, and not to know their play is simply to be not a chessplayer. The reason is simple: a Wimbledon final by Wilding or an innings by Trumper are now “one with yesterday’s 7,000 years” or exist merely as vague images in the minds of a small and ever diminishing number of surviving spectators. But Capablanca’s games can be played over again and again by chessplayers anywhere and any time just as Capablanca played them. Certainly there are many who can “play chess” and have never played over a Capablanca game, but anyone who confesses to it is not recognized as a chessplayer among chessplayers.

And yet he may be able to beat some players in the real chess world. That does not matter. He is still not one of them. Chess is not only a game but an art.’

10154. Gromer

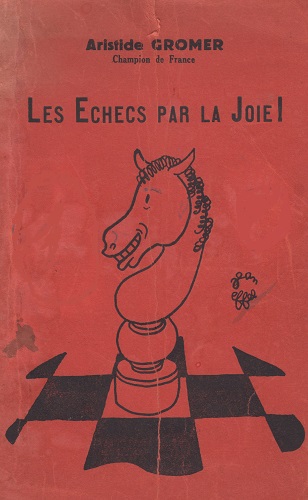

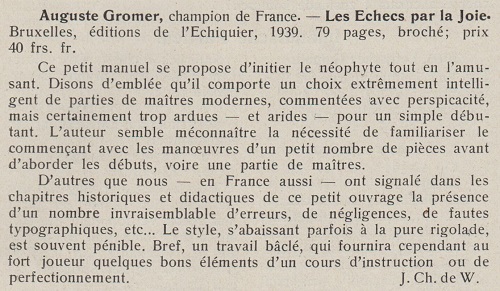

From page 5 of Les échecs par la joie by Aristide Gromer (Brussels, 1939):

‘Depuis Jésus-Christ, quantité de personnages illustres ont dédié une partie de leur temps au jeu d’échecs.’

Page 105 of the July 1940 Schweizerische Schachzeitung had a text-book example (by Jean-Charles de Watteville, with ‘Auguste’ instead of Aristide) of a damning review which ends on an artificially positive note:

10155. Jean Dufresne

Source: page 136 of Pocket Book of Chess by Raymond Keene (London, 1988). Such gaffes are two a penny in his oeuvre; see too both editions of Soltis’ Chess Lists book, on pages 104 and 145 respectively.

A curiosity, though, is that even two respected writers made the same mix-up over Jean Dufresne (real name) and E.S. Freund (pseudonym). From page 202 of the Dizionario enciclopedico degli scacchi by A. Chicco and G. Porreca (Milan, 1971):

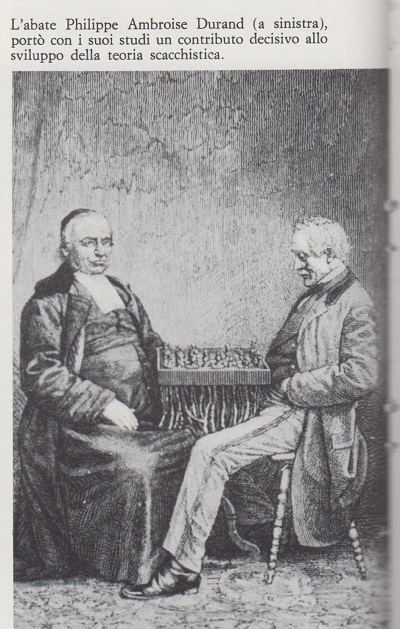

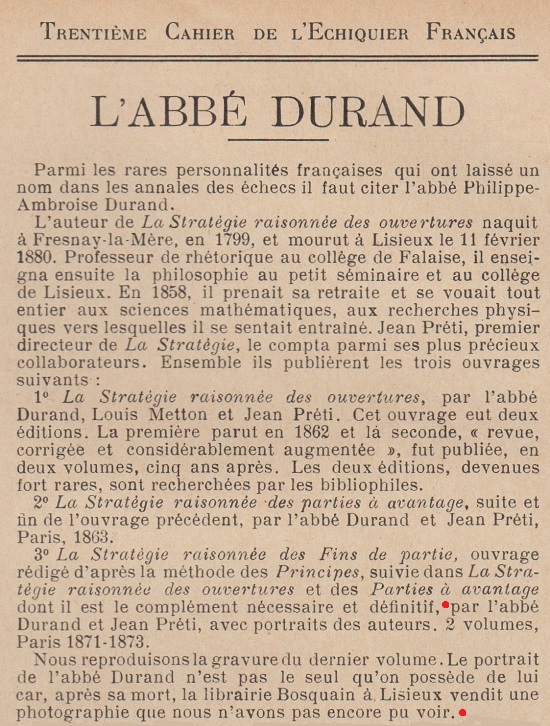

10156. Philippe Ambroise Durand

The above is from a plate section in the 1971 reference work mentioned in the previous item, Chicco and Porreca’s Dizionario enciclopedico degli scacchi.

The article on page 203:

Below is the entry on Durand in the unpublished 1994 edition of Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia:

There was a good-quality reproduction of the picture of Durand and Jean-Louis Preti on page 418 of the 30th issue of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français (1932), and the previous page provided information about its source, with a reference to another portrait of Durand:

A marked contrast exists between the obscurity of Durand’s name nowadays and the high praise bestowed upon him in the French magazine and Italian book.

10157. Durand and Maizelis

Two positions credited to Philippe Ambroise Durand (C.N. 10156) were included, on pages 92 and 95, in Maizelis’ book Shakhmaty (C.N. 10147).

In the English translation by John Sugden, The Soviet Chess Primer (Glasgow, 2014), the Durand positions are on pages 140 and 146.

The book includes a Foreword by Emanuel Lasker (‘Moscow, January 1936’) from the original Soviet edition; entitled ‘The Meaning of Chess’, it is a general essay and not a discussion of Maizelis’ book. Quality Chess did, however, include a new Foreword by Mark Dvoretsky which praised the 1960 edition highly (‘Having studied the Chess book, I scored 10 out of 10 in my next tournament ...’). The cover features strong recommendations by both Kasparov and Karpov:

10158. Alekhine position

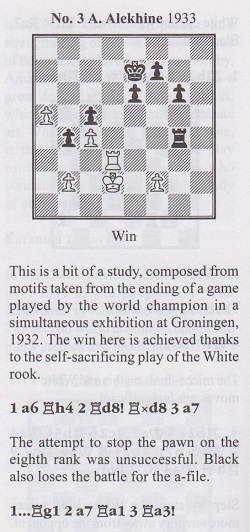

From page 166 of Studies for Practical Players by Mark Dvoretsky and Oleg Pervakov (Milford, 2009), translated by Jim Marfia:

‘It often happens that a game, or the analysis which follows, will produce study-like positions. Some do not require any sort of further finishing work – they stand before us practically ready-made. Others are more like diamonds in the rough, awaiting further polishing. Alekhine had those kinds of positions, too.’

There followed this ‘bit of a study’:

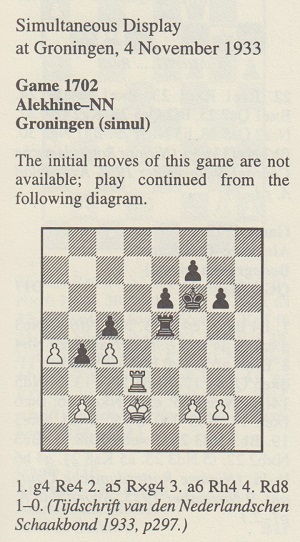

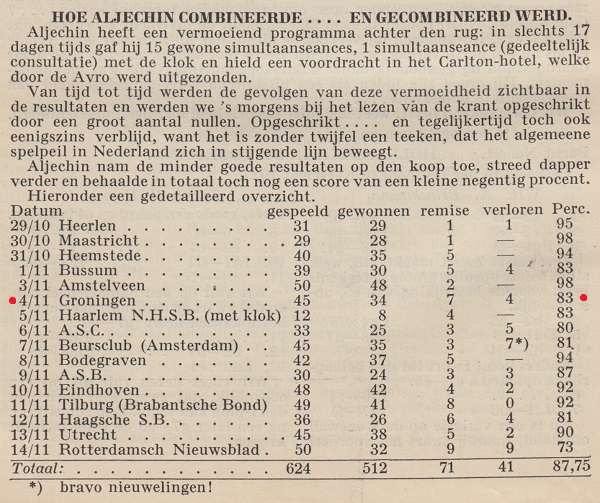

Leaving aside, in the above extract, the incorrect date (1932) and the notational mishap, we observe that, as usual, Alexander Alekhine’s Chess Games, 1902-1946 by L.M. Skinner and R.G.P. Verhoeven (Jefferson, 1998) is the source to consult. From page 475:

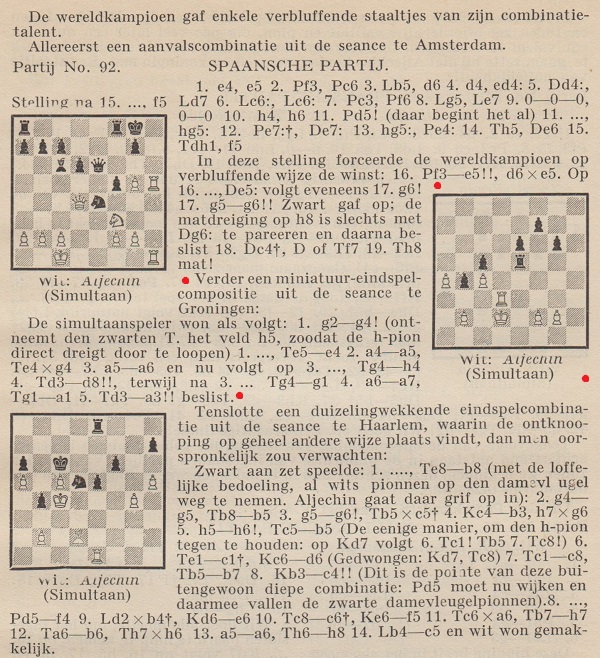

Below is the coverage on pages 296-297 of the Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond, November 1933:

Did any newspapers of the period offer further information about the game played in Groningen?

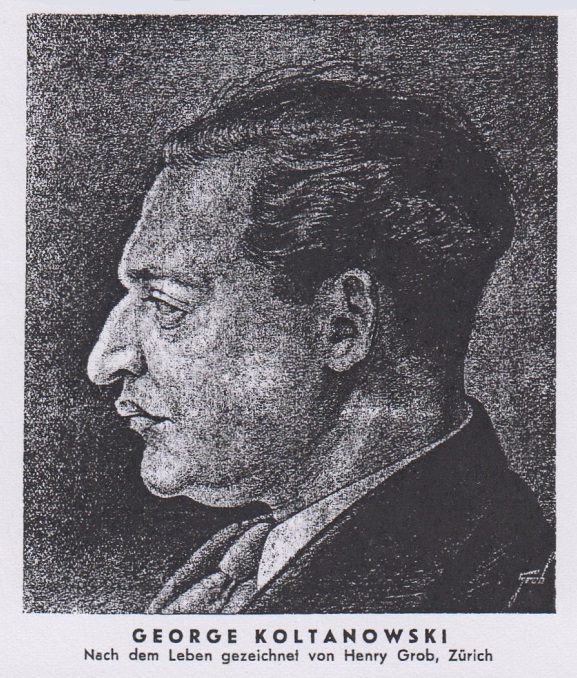

10159. A portrait of Koltanowski by Grob

From page 1 of the 4 December 1936 issue of Schach-Kurier:

10160. Utter uselessness

‘The development of the idea that playing chess is self-justifying ran parallel to or perhaps was an offshoot of the development of the idea of art for art’s sake. It reached its epitome at the end of the nineteenth century in the formula of Ernst Cassirer: “What chess has in common with science and fine art is its utter uselessness.”’

That comes from pages 52-53 of Crescendo of the

Virtuoso by Paul Metzner (Berkeley and Los Angeles,

1998). An endnote reference 87 invites the reader to turn

to page 308 for the source of the Cassirer quote. Will it

be a weighty philosophical tome from the late nineteenth

century? No:

Reinfeld also gave the Cassirer quote, again without a source, on page 287 of The Joys of Chess (New York, 1961).

In reality, there was nothing weighty about Cassirer’s remark. From pages 37-38 of Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood by Edward Lasker (Philadelphia, 1942):

‘Ernst Cassirer once said to me jokingly that what chess has in common with science and fine art is its utter uselessness. I am sure I discerned a note of praise in this remark which was not unconscious. If one were to condemn chess just because it is useless in the utilitarian sense of the word, one might, on the same basis, reject all but commercial art and many branches of higher mathematics which can hardly have any practical application.’

Pages 15-18 of the book reproduced a letter from Cassirer to Lasker which evinced a deep love of the game.

On pages 27-28 of Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters (New York, 1951) Edward Lasker related his meetings with Cassirer and Emanuel Lasker, during which the latter’s philosophy was discussed.

10161. Lasker’s Manual

The two Dover editions (respective prices: $2.75 and $5.50) referred to in C.N. 10146:

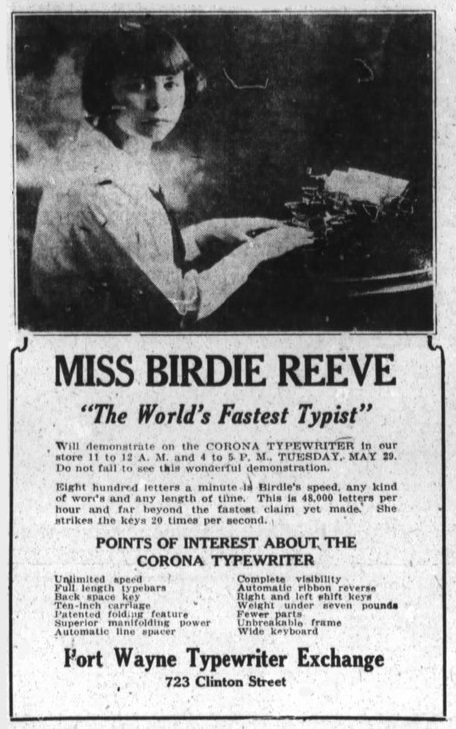

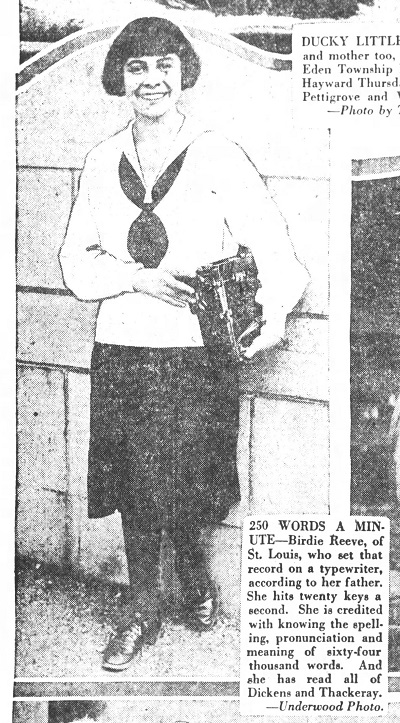

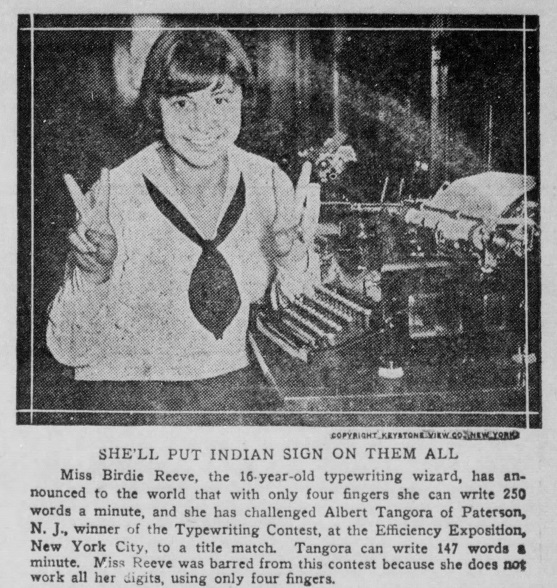

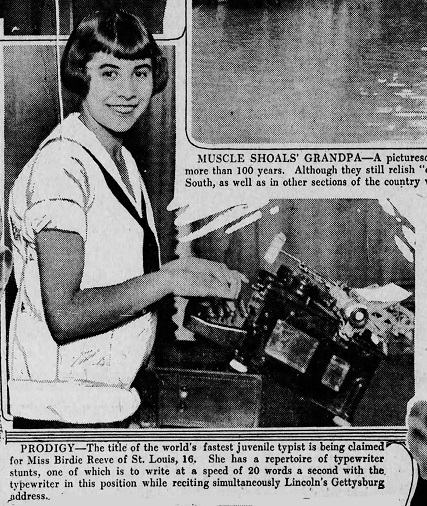

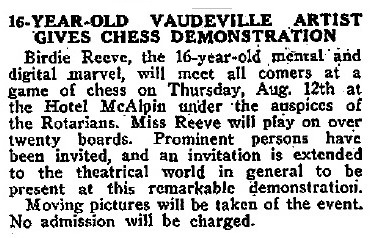

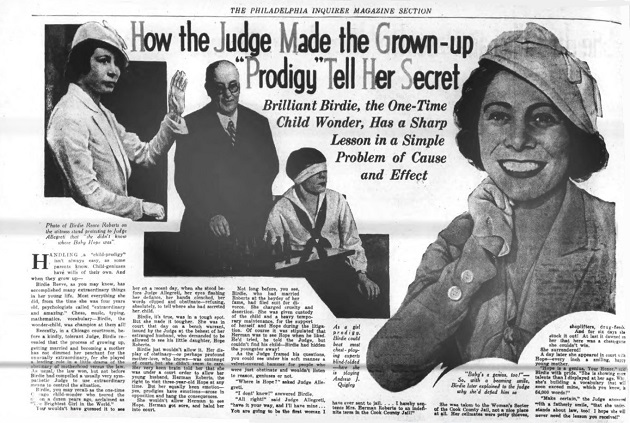

10162. Birdie Reeve

Ulrich Schimke (Cologne, Germany) mentions that the Trove website has a number of newspaper reports about Birdie Reeve, including the following:

‘Miss Birdie Reeve, Chicago’s memory prodigy, competed successfully in a simultaneous chess match with 20 players at the City Club. The girl played blindfolded, directing her moves after the plays of the opponents had been read to her. Unfailingly she visualized each situation she had to meet. Miss Reeve also claims honors as the world’s speediest typist.’

Source: Richmond River Herald, 20 April 1928, page 2.

We add from other sources a sequence of cuttings about

Birdie Reeve, who, it was reported in the late 1920s,

‘claims the women’s chess championship of the world’:

Salem News, 1 March 1922, page 1

New Castle Herald, 28 March 1923, page 7

Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, 29 May 1923, page 2

Oakland Tribune, 30 July 1923, page 19

Courier-Gazette, 17 November 1923, page 2

Altoona Tribune, 14 June 1924, page 12

Vaudeville News and New York Star, 13 August 1926, page 7

Harrisburg Telegraph, 21 February 1928, second section, page 1

Philadelphia Inquirer, magazine section, 11 August 1935

10163. From former times

C.N. 10162 included this cutting from page 7 of the New Castle Herald, 28 March 1923:

The caption prompts us to give the following:

CHESS, 14 September 1935, page 19

CHESS, May 1949, page 195

CHESS, End-December 1965, page 129.

10164. Gloria Velat (C.N. 10163)

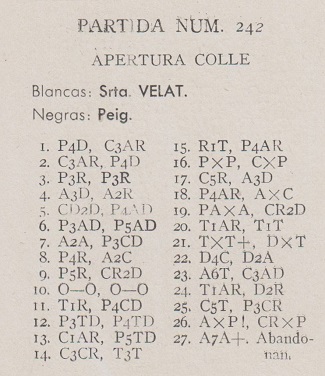

From page 349 of El Ajedrez Español, July 1935:

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 d5 3 e3 e6 4 Bd3 Be7 5 Nbd2 c5 6 c3 c4 7 Bc2 b6 8 e4 Bb7 9 e5 Nfd7 10 O-O O-O 11 Re1 b5 12 a3 a5 13 Nf1 a4 14 Ng3 Ra6 15 Kh1 f5 16 exf6 Nxf6 17 Ne5 Bd6 18 f4 Bxe5 19 fxe5 Nfd7 20 Rf1 Ra8 21 Rxf8+ Qxf8

22 Qg4 Qf7 23 Bh6 Nc6 24 Rf1 Qe7 25 Nh5 g6 26 Bxg6 Ndxe5 27 Bf7+ Resigns.

Annotations to the game (played in Barcelona in 1935) by Ramón Rey Ardid are available on-line: La Vanguardia, 31 May 1935, page 14.

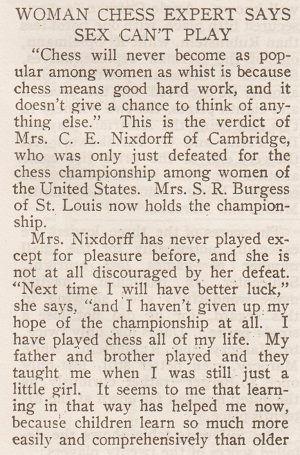

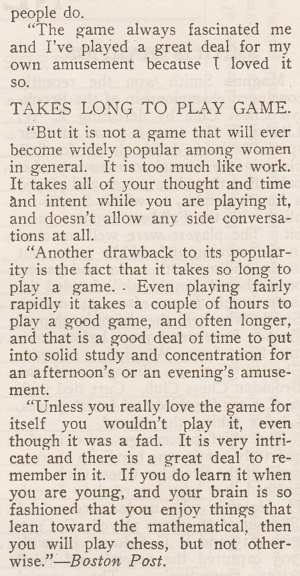

10165. Burgess v Nixdorff

‘Chess will never become as popular among women as whist is because chess means good hard work, and it doesn’t give a chance to think of anything else.’

‘... it is not a game that will ever become widely popular among women in general. It is too much like work. It takes all of your thought and time and intent while you are playing it, and doesn’t allow any side conversations at all.’

Those remarks, by Mrs Charles Edward Nixdorff, are taken from an article in the Boston Post (can a reader supply that original publication?) which was reproduced on page 24 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, April 1908:

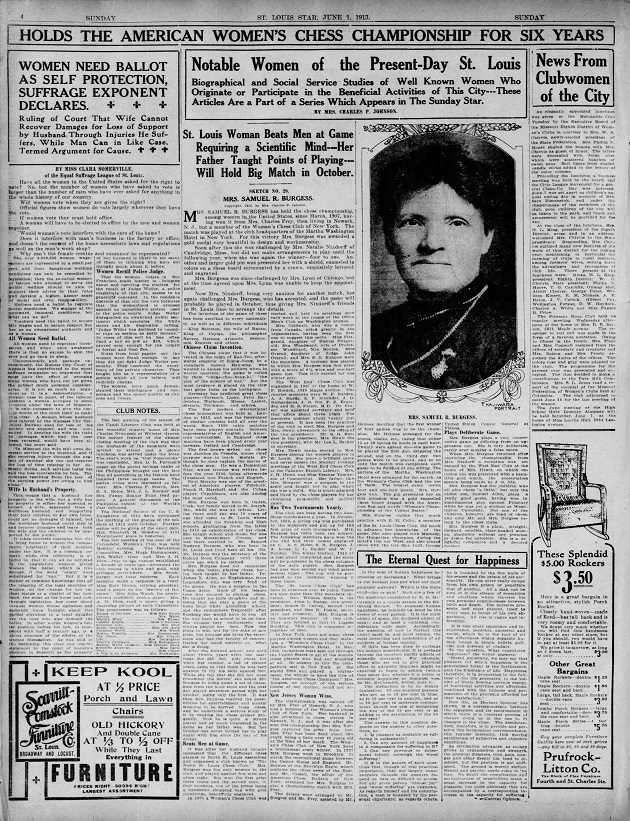

The match between Mrs Burgess and Mrs Nixdorff for the US women’s championship was played in the Hotel Martha Washington, 29 East 29th Street, New York on 20-25 February 1908, and a report with all five game-scores was published on pages 96-97 of the May 1908 American Chess Bulletin. Mrs Burgess lost the third game and won the other four.

A feature about her on page 4 of the St Louis Star, 1 June 1913:

10166. Lasker’s Manual (C.N. 10161)

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) has another edition issued by Dover Publications, Inc. (priced at $2.50):

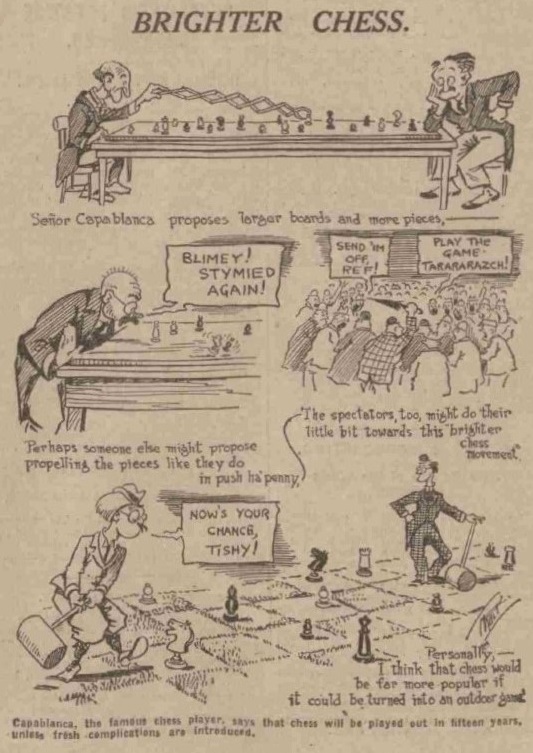

10167.

Brighter chess

From Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) comes this item on page 7 of the Leeds Mercury, 28 November 1928:

10168. Political leaders and self-knowledge

President Josiah Bartlet (Martin Sheen) in an episode of The West Wing (C.N. 6129)

From pages 70-71 of Play All by Clive James (New Haven and London, 2016):

‘In The West Wing the purity of language is unreal: network rules prevail and we never hear a dirty word. Nor does anyone, not even a writer, ever really talk that well. But there is realism about the way reasoned conclusions are reached.

In that regard, the most advanced stroke of realism in the show is the way that not even the brilliant Bartlet can function without hearing other voices. Those of us who hanker for a father figure should remember that if he existed then he would need a father figure too. Though Bartlet is a mighty chess player, The West Wing is a pretty good shot at fighting off the romanticism by which the central guru can understand the whole board at a glance. In I, Claudius Augustus sometimes didn’t know what was really going on, but he didn’t know that he didn’t know. Bartlet incarnates Camus’s definition of democracy as the system built and maintained by those who know that they don’t know everything.’

Chess references in The West Wing are discussed in Chess and Television. See too Clive James and Chess.

Below from our collection is a photograph signed by cast members of The West Wing in 2002:

Left to right: Allison Janney, Richard Schiff, John Spencer, Martin Sheen, Rob Lowe, Dulé Hill and Bradley Whitford.

10169. A moss-grown trap

Black played 29...Qxd5

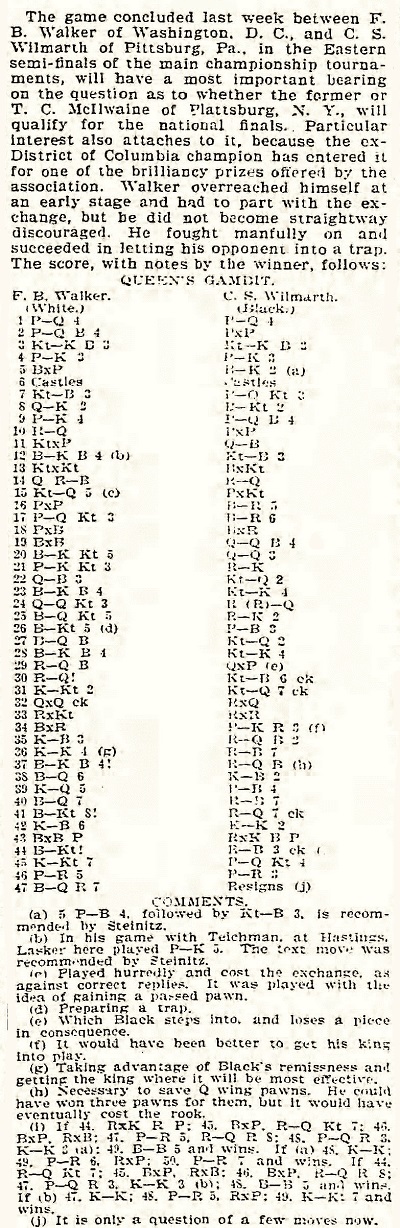

A characteristic comment by W.E. Napier concerning a correspondence game between F.B. Walker and C.S. Wilmarth:

‘Blundering into a moss-grown trap, which might easily have been avoided by K-R sq. When the king stands on the ultimate square of a file or diagonal, commanded by an adverse piece, no matter how many pieces or pawns intervene, it argues foresight in a player, if provision be made for possible discomfiture.’

Source: American Chess World, February 1901, page 41.

The periodical reproduced the winner’s notes from page 9 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 23 December 1900:

1 d4 d5 2 c4 dxc4 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 e3 e6 5 Bxc4 Be7 6 O-O O-O 7 Nc3 b6 8 Qe2 Bb7 9 e4 c5 10 Rd1 cxd4 11 Nxd4 Qc8 12 Bf4 Nc6 13 Nxc6 Bxc6 14 Rac1 Rd8 15 Nd5 exd5 16 exd5 Ba4 17 b3 Ba3 18 bxa4 Bxc1 19 Bxc1 Qc5 20 Bg5 Qd6 21 g3 Re8 22 Qf3 Nd7 23 Bf4 Ne5 24 Qb3 Rad8 25 Bb5 Re7 26 Bg5 f6 27 Bc1 Nd7 28 Bf4 Ne5 29 Rc1 Qxd5 30 Rd1 Nf3+ 31 Kg2 Nd2+ 32 Qxd5+ Rxd5 33 Rxd2 Rxd2 34 Bxd2 h6 35 Kf3 Rc7 36 Ke4 Rc2 37 Bf4 Rc8 38 Bd6 Kf7 39 Kd5 f5 40 Bd7 Rc2 41 Bb8 Rd2+ 42 Kc6 Ke7 43 Bxf5 Rxf2 44 Bb1 Rf6+ 45 Kb7 b5 46 a5 a6 47 Ba7 Resigns.

10170. Luck

Regarding Luck in Chess, below is an observation by C.J.S. Purdy at the start of his article ‘The Element of Chance in Chess’ on pages 171-172 and 184 of Chess World, August 1957:

‘Chess is so complex that the result of any particular game is partly a matter of luck. Over a series of games the slightly stronger player should win, but in an individual game one can only say that he has slightly better than an even chance; anything can happen.

Chess is far more “flukey”, for instance, than tennis, squash or billiards. In those games, a single bad blunder rarely spells disaster; in chess, often.’

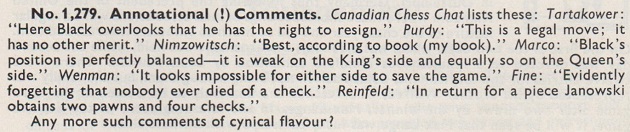

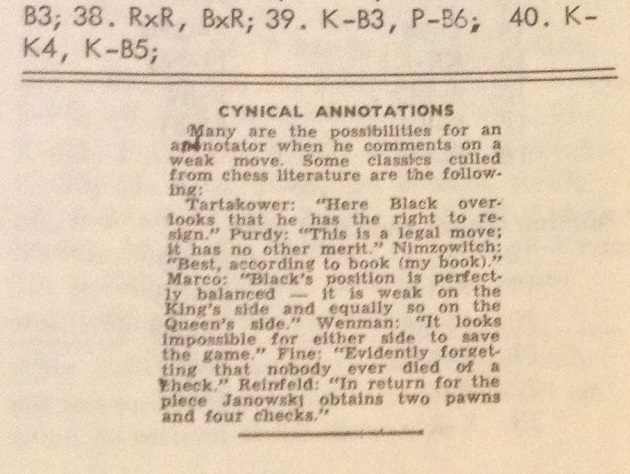

10171. Annotations

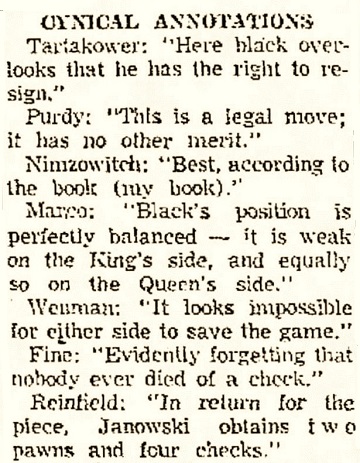

From page 278 of the September 1963 BCM, in D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column:

It will be appreciated if a reader can provide the item published in Canadian Chess Chat. For now, we give an extract from a column by George Koltanowski on page 10 of the Corpus Christi Caller-Times, 20 May 1962:

As ever, factual information about such quotations is sought. The Marco one was discussed in C.N. 5248, and the remark ascribed to Reinfeld should also mention Fine. It appeared on page 141 of the book on Lasker which they co-authored.

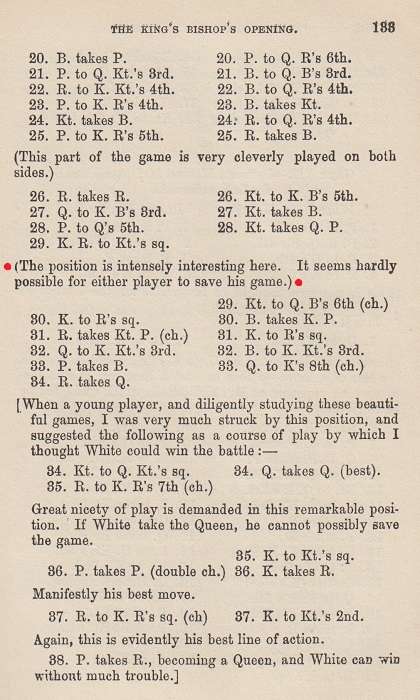

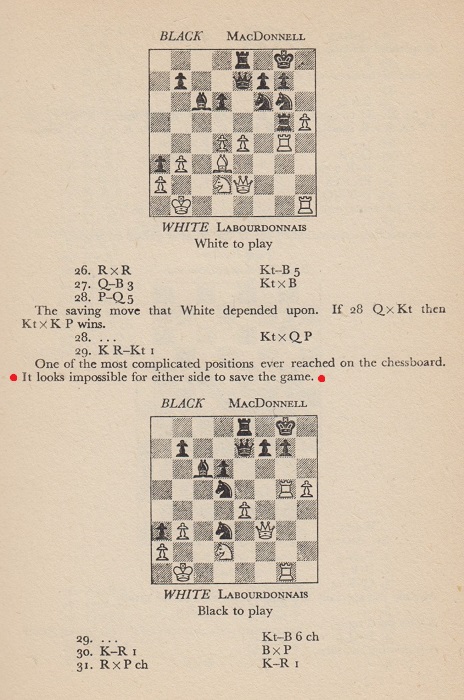

It is, though, the Wenman item that deserves particular attention, since it brings to mind a remark widely attributed to Staunton. For example, an article by G.H. Diggle reproduced in C.N. 7369 stated with regard to writers who annotated the 1834 Labourdonnais v McDonnell games:

‘Staunton himself, who did so (Chess Player’s Chronicle, volumes 1-3), really sums up the series in a famous note to game 21: “It seems utterly impossible for either player to save the game.”’

In an article about the Labourdonnais v McDonnell series on pages 277-281 of the July 1934 BCM Diggle wrote:

‘Some of their complications have driven annotators to despair. Staunton himself in one case can do no more than helplessly declare: “It seems utterly impossible for either player to save the game.”’

The article was reproduced on pages 69-75 of The Treasury of Chess Lore by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1951).

Presenting game 21 on pages 94-95 of Lessons in Chess Strategy (London, 1968) W.H. Cozens wrote:

‘Staunton’s note after White’s 29th move makes an apt comment: “It now seems hardly possible for either player to save the game.”’

However, pages 83-84 of The World of Chess by Anthony Saidy and Norman Lessing (New York, 1974) had the following with regard to a different game (50):

‘Beyond inserting a number of exclamation points it is useless to try to annotate this wildly uninhibited game. Howard Staunton, the famous English player, made the attempt some years later, only to give up with the historic remark: “It seems utterly impossible for either player to save the game!”’

It took us a while to find confirmation of Staunton’s words (in connection with game 21), on page 133 of his posthumous book Chess: Theory and Practice (London, 1876). Below is the relevant page in a late edition (London, 1920, published under the title The Laws and Practice of Chess):

That leaves the question of why Wenman’s name was introduced for a similar remark, and we can give a citation from his book One Hundred and Seventy Five Chess Brilliancies (London, 1947):

That unnumbered page is game 53 in Wenman’s book and is, of course, part of his coverage of the above-mentioned game 21 in the Labourdonnais v McDonnell series.

10172. Two Alekhine notes

Which move is preferable, 5 d3 or 5 e3?

On pages 67 and 265 of his book on Nottingham, 1936 Alekhine gave contradictory comments about the position after 1 c4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 g3 g6 4 Bg2 Bg7:

As mentioned in C.N. 2109 (see page 281 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves), the discrepancy was pointed out by T.V. Parrott on page 153 of CHESS, May 1953 and by Arthur Oliver on page 105 of Chess World, June 1962. A later reference is page 15 of Chess Life, January 1963 (in a ‘Chess Kaleidoscope’ article by Eliot Hearst).

10173. ‘Known on the Continent as ...’

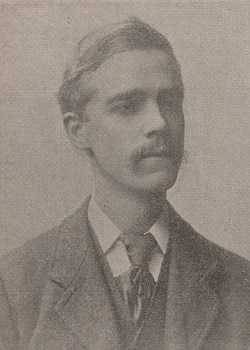

Henry Ernest Atkins (BCM, October 1897, page 382)

- ‘The story has often been told how Atkins made a deep study of Steinitz’s games and modelled his play so closely on that of his master that he was known on the Continent as “Der kleine Steinitz” (“little Steinitz”).’

A Treasury of British Chess Masterpieces by Fred Reinfeld (London, 1950), page 70.

- ‘Another important influence in the formation of his style was Steinitz, then world champion, so that in later years he was known on the Continent as “the little Steinitz”.’

H.E. Atkins Doyen of British Chess Champions by R.N. Coles (London, 1952), page 2.

- ‘Atkins was known on the Continent as the “little Steinitz” and this would be no bad description of Penrose.’

Harry Golombek, in The Times (Review section), 7 September 1968, page 23.

- ‘He was known on the Continent as “the little Steinitz”.’

Entry on Atkins, by Raymond Keene, in The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977), page 17.

- ‘H.E. Atkins, known on the Continent as “the little Steinitz”...’

Harry Golombek, The Times (Review section), 29 August 1981, page 12.

A source for this claim about Atkins is never specified, and the best that we can offer is the following, from page 34 of the first (1922) issue of Chess Pie:

To what extent was Atkins ever known ‘on the Continent’ as ‘the little Steinitz’? More generally, even if nicknames of this sort can be corroborated, their purpose and value are far from clear.

10174. Journalistic longevity

Beyond the entries in Chess Records, we should like to list exceptional achievements in chess journalism (e.g. long-running magazines or newspaper columns), whether or not a single individual was involved throughout. The exploits need not necessarily be world, or even national, records.

10175. Photographs at a Finnish website

Many excellent photographs can be viewed at the Finna website by entering the Finnish word for chess, ‘shakki’.

10176. Two Alekhine notes (C.N. 10172)

Position after 4...Bg7

From Yasser Seirawan (Amsterdam):

‘Despite Alekhine’s contradictory comments, both the moves that he mentions, 5 d3 and 5 e3, are considered to be main lines of play in modern opening theory.

In his recent works on the English Opening, Mihail Marin has advocated 5 e4, and I wonder whether Alekhine might have suggested that that move weakens f3, d3 and d4. The most surprising comment by Alekhine is that after 5 d3 White may, in time, aspire to play f4; in modern games that simply does not happen.

In view of the forthcoming middlegame, modern masters would judge 5 d3 to be the prelude to a queen’s-side expansion, most often seen with the maneuver Rb1, b4 and b5, chasing away the c6-knight and improving the view of the g2 bishop.

Conversely, 5 e3 is considered rather more flexible. White signals that he intends a central expansion with Nge2, perhaps followed by the advance d4. In that line, White can sometimes also pursue a queen’s-side expansion, as mentioned above, after playing d3. The key difference is that the king’s knight is developed to e2 instead of f3, and in this case White will usually play f4, to counter-act an aggressive king’s-side expansion by Black.

In short, modern theory considers that the two moves given by Alekhine, 5 d3 and 5 e3, are equally good.’

10177. Henry Edward Bird

H.E. Bird by Hans Renette (Jefferson, 2016) is one of the best-researched chess books that we have ever seen.

10178. Alan Bennett (C.N.s 6663 & 6670)

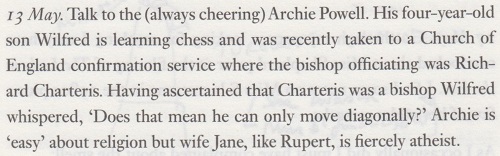

Another diary entry by Alan Bennett, dated 13 May 2015, from page 355 of his book Keeping On Keeping On (London, 2016):

10179. John Finch

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘Chess literature contains a number of references to a player named Finch, a familiar figure in London chess circles during the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s, and notably at Ries’ Divan in the Strand.

In Chess Studies (London, 1844) George Walker supplied two games (217 and 218) won by Alexander McDonnell against “Mr F*n*h” at the odds of the queen’s rook, in a chapter entitled “Games played by M’Donnell from about 1832 to 1835”. Later, “Finch, esq.” was a subscriber to William Greenwood Walker’s book on McDonnell (London, 1836).

Finch evidently played his moves quickly. A footnote on page 50 of Philip W. Sergeant’s A Century of British Chess (London, 1934) had two lines of D’Arblay’s poem Caïssa Rediviva (London, 1836) which contrasted Finch’s rapid play with Popert’s slowness:

“And slow P[opert], who inch by inch

Disputes the ground; and rapid F[inch],”D’Arblay’s allusion to Finch was completed with these words:

“Who never from th’exchange did flinch.”

At some stage Finch became a professional. Charles Tomlinson’s reminiscences about the Divan on pages 46-54 of the February 1891 BCM included the following (on page 52):

“There was a man named Finch, for example, whose moves were all stereotyped, as well as his traps and catches. He generally tried to evade giving odds by complimenting the amateur on his strength. On one such occasion an incident occurred which became a standing joke in the Divan. A clergyman introduced to Finch by Simpson sat down before him and assented to the customary “play for a shilling?”. He lost about a dozen games, and then got up and deposited a shilling on the board, and would not be persuaded that a shilling a game was intended.”

In 1849 Finch took part in a strong tournament at Ries’ Divan, during which he lost 1-2 to J.R. Medley. He was referred to as John Finch on page 66 of that year’s volume of the Chess Player's Chronicle.

During some casual games which Adolf Anderssen played after his victory in the London, 1851 tournament, Finch defeated him in a well-known game (published on page 91 of the New Chess Player in 1852).

Daniel Willard Fiske commented on page 401 of the New York, 1857 tournament book:

“In the latter years of the decade which witnessed the advent of the Automaton, a Frenchman, by the name of Blin, opened a Chess-room in Warren Street, where the members of the New York Club probably held their meetings. The leading players of that time were Henry J. Anderson, Ezra Weeks, Judge Theodore S. Fisk, Elkanah Watson, I. Finch, William Coleman, Antonio Rapallo and E. Macgauran. Of these, Mr Finch was an Englishman who spent some years in this country and Canada. Upon his return to England he published an account of his travels, wherein he gives abundant evidence of his fondness for the game. Afterwards he was a frequent visitor to the clubs and divans of London, and a game is extant between him and the great M’Donnell.”

It is clear from the latter part of this passage that Fiske was referring to the same Finch who is under discussion here. The “account of his travels” alludes to Finch’s 1833 work Travels in the United States of America and Canada. The title page bears the author’s name as “I. Finch”, where “I” is, presumably, intended to be short for “Ioannes” – a style more in keeping with the seventeenth century than the nineteenth.

The Library and Archives of Harris Manchester College, Oxford holds a manuscript by Tony Rail, dated April 2012, which contains information about the life of John Finch. It is entitled “Biographical notes for William Steill Brown and his wife Eliza Finch, a granddaughter of Dr Joseph Priestley with some genealogical notes of their descendants and some biographical notes for John Finch (1791-1854)”.

Tony Rail notes the birth of John Finch at Heath Forge, Wombourne, Staffordshire, on 17 September 1791; he was the younger son of William Finch and Sarah Priestley. Confirmation of such a birth is to be found in a nonconformist register (RG5/26) deposited at the National Archives; the record states that John’s mother was a daughter of Joseph and Mary Priestley and that a surgeon, J. Wainwright, was present at the birth, which was later registered at Dr Williams’s Library, Redcross Street, near Cripplegate, London, on 24 June 1802. His baptism took place on 4 November 1791 at a nonconformist chapel in Wolverhampton Street, Dudley, Worcestershire (National Archives, RG4/2736, p. 9). This was the Old Meeting House in Dudley, with which John’s Finch ancestors had been associated for several generations. Earlier, the chapel’s congregation had been Presbyterian, but it became Unitarian.

The Tony Rail manuscript states that Finch, having become interested in geology early in life, left London in November 1822, on the packet-boat Acasta, bound for New York. He gave several series of lectures on geology and mineralogy, and in 1825 he visited Virginia, where he met the former US Presidents James Madison and Thomas Jefferson at their respective tobacco plantations of Montpelier and Monticello. If this account is correct, the conversation involving Jefferson referred to in C.N. 8071 took place in 1825. The 1851 census finds Finch at 33 Kenton Street, Brunswick Square, London, where he was described as aged 58, unmarried, “Author History Science &c.”, born at Dudley, Worcestershire (source: National Archives, HO 107/1507, f. 27). Later Kenton Street was the place of his death, and an entry for him appears in the burial register of St James’s Highgate Cemetery, dated 22 February 1854.

John Finch should not be confused with James Gayler Finch, who was a problemist and player of a later period.‘

10180. An alleged Anderssen remark

An addition to How Many Moves Ahead? will be this ‘once’ claim from page 15 of American Chess World, January 1902:

‘Anderssen, the chess expert, was once asked by a lady how far ahead he could see in a game of chess, and he replied that when he tried very hard he could see one move ahead.’

A ‘once’ version involving Zukertort and another, or perhaps the same, lady was quoted in C.N. 7090 from pages 208-209 of the September 1914 American Chess Bulletin:

‘It is said that a lady once admiringly asked Zukertort how many moves he could see ahead, and that he replied, “Madam, if the position is sufficiently simple, and I look a long time, I can sometimes see ‘one’ move ahead.”’

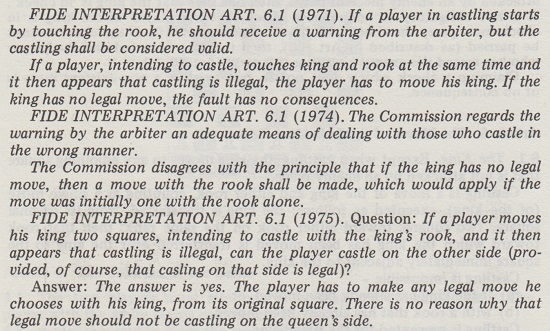

10181. How to castle (C.N.s 10077 & 10081)

As regards the admissibility or otherwise of castling by first touching the rook, Joose Norri (Helsinki) refers to pages 135-136 of The Chess Competitors’ Handbook by B.M. Kažić (London, 1980).

Firstly, part of Article 6.1 of the Laws, as quoted on page 135:

‘Castling is a move of the king and either rook, counting as a single move (of the king), executed as follows: the king is transferred, from its original square, two squares toward either rook on the same rank; then that rook toward which the king has been moved is transferred over the king to the square immediately adjacent to the king.’

From page 136:

A Spanish version of these interpretative texts was shown in C.N. 9492, from pages 123-124 of Aprenda ajedrez by Luciano W. Cámara (Buenos Aires, 1977).

10182. Annotations (C.N. 10171)

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, Canada) sends, courtesy of Stephen Wright, the requested item in Canadian Chess Chat (page 45 of the February 1963 issue):

As shown in C.N. 10171, George Koltanowski had presented the same set of quotes, also without any sources, in a newspaper column about nine months previously. We should particularly like to know more about the remark attributed to Purdy.

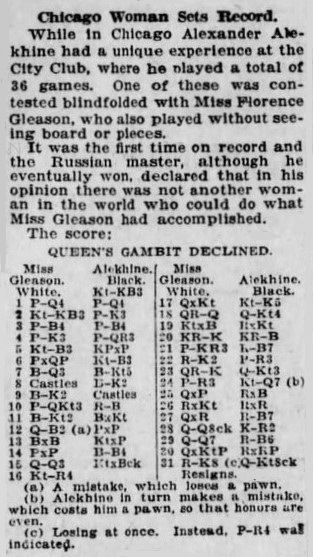

10183. Florence Gleason v Alekhine

On page 43 of issue 27 of Kingpin (Summer 1997) we discussed Gleason v Alekhine, Chicago, 9 February 1924, which both sides played blindfold. (See pages 305-306 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.)

The score as given on page A3 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 21 February 1924:

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 d5 3 c4 e6 4 e3 c5 5 Nc3 a6 6 cxd5 exd5 7 Bd3 Nc6 8 O-O Bg4 9 Be2 Be7 10 b3 O-O 11 Bb2 Rc8 12 Qc2 Bxf3 13 Bxf3 cxd4 14 exd4 Nxd4 15 Qd3 Bc5 16 Na4 Nxf3+ 17 Qxf3 Ne4 18 Rad1 Qg5 19 Nxc5 Rxc5 20 Rfe1 Rfc8 21 h3 Rc2 22 Re2 h6 23 Rde1 Qg6 24 a3 Nd2 25 Qxd5 Rxb2 26 Rxd2 Rxd2 27 Qxd2 Rc2 28 Qd8+ Kh7 29 Qd7 Rc3 30 Qxb7 Rxh3 31 Re8 Qb1+ 32 White resigns.

A photograph taken during Alekhine’s exhibition, with Florence Gleason mentioned in the caption, was shown in C.N. 4985. Information about her is still sought.

10184. Alekhine in a Clive James poem

From page 55 of Other Passports by Clive James (London, 1986):

The full poem, a parody entitled ‘Richard Wilbur’s Fabergé Egg Factory’, can be read on Clive James’s website.

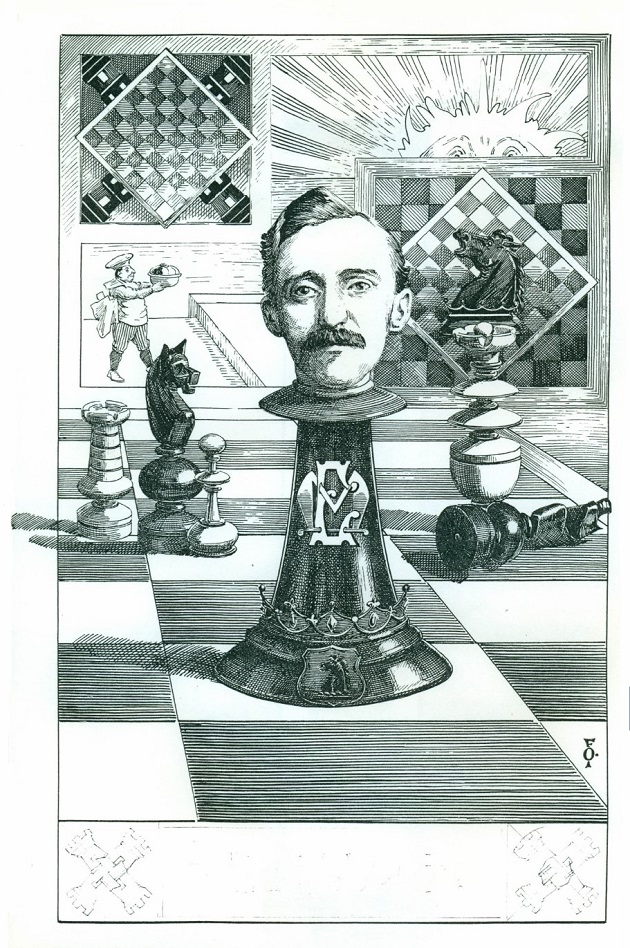

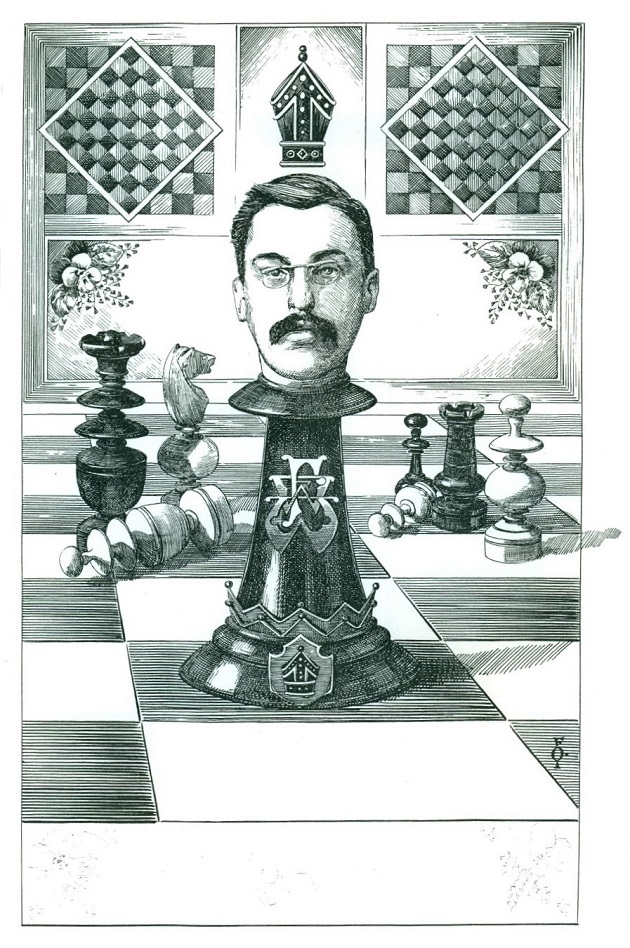

10185. Frederick Orrett

The series of portraits provided by Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) continues with two tentatively identified by our correspondent as Edward Millins and Frank Wilson Wynne:

10186. Journalistic longevity (C.N. 10174)

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) draws attention to his article on A.J. Neilson, whose chess column in the Falkirk Herald ran from 1894 to 1942.

Russell Miller (Vancouver, WA, USA) mentions that the magazine now entitled Northwest Chess began in 1947 and has been published nearly every month since then.

10187. Curt v Bixby

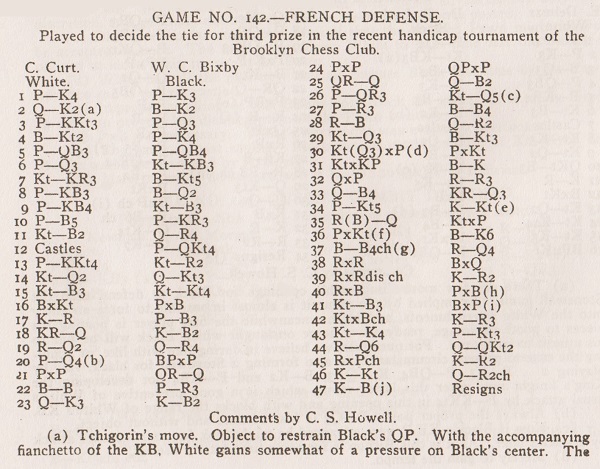

From pages 38-39 of American Chess World, February 1902:

1 e4 e6 2 Qe2 Be7 3 g3 d6 4 Bg2 e5 5 c3 c5 6 d3 Nf6 7 Nh3 Bg4 8 f3 Bd7 9 f4 Nc6 10 f5 h6 11 Nf2 Qa5 12 O-O b5 13 g4 Nh7 14 Nd2 Qb6 15 Nf3 Ng5 16 Bxg5 hxg5 17 Kh1 f6 18 Rfd1 Kf7 19 Rd2 Qa5 20 d4 cxd4 21 cxd4 Rad8 22 Bf1 a6 23 Qe3 Kf8 [23...K-B2 was corrected to 23...K-B1 on page 65 of the March 1902 issue.] 24 dxe5 dxe5 25 Rad1 Qc7 26 a3 Nd4 27 h3 Bc5 28 Rc1 Qa7 29 Nd3 Bb6 30 Ndxe5 fxe5 31 Nxe5 Be8 32 Qxg5 Rh6 33 Qf4 Rhd6 34 g5 Kg8 35 Rcd1 Nxf5 36 exf5 Be3

37 Bc4+ Rd5 38 Rxd5 Bxf4 39 Rxd8+ Kh7 40 Rxe8 bxc4 41 Nf3 Bxg5 42 Nxg5+ Kh6 43 Ne4 g6 44 Rd6 Qb7 45 Rxg6+ Kh7 46 Kg1 Qa7+ 47 Kf1 Resigns.

10188. Constantine Rasis

‘Some Chess Memories’ by Constantine Rasis on pages 105-106 of the April 1963 Chess Life included observations on his play against Alekhine, Marshall, Lasker and Reshevsky (mainly in simultaneous exhibitions), but had no game-scores. A loss to Lasker (Hamilton, 25 August 1939) was given in K. Whyld’s collections of games by Lasker (published in 1976 and 1998), but what else can be found?

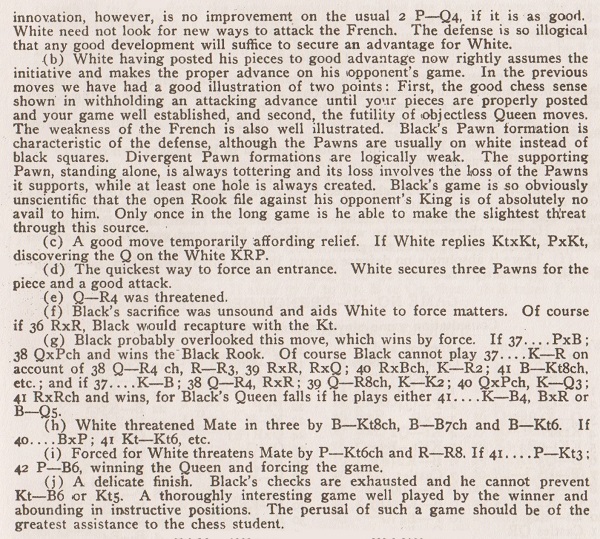

In Chess Life Rasis recalled an encounter with Alekhine in Detroit after [sic] the New York, 1924 tournament:

10189. New York, 1924

From the Detroit Free Press (Rotogravure Supplement), 23 March 1924:

From left to right: Efim Bogoljubow, Géza Maróczy, Richard Réti, Emanuel Lasker, Savielly Tartakower

10190. Photographic archives (24)

Another set of photographs from our collection:

Florencio Campomanes,

Miguel Najdorf, Kirsan Ilyumzhinov (Yerevan, 1996)

Božidar Gašić (inscribed by him on the reverse: Belgrade, 16 February 1998)

Eduard Gufeld

Martin E. Morrison

Lothar Schmid

| First column | << previous | Archives [147] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.