Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [149] | next >> | Current column |

10237. A fake Karjakin v Carlsen photograph

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘This picture, which originated on an anonymous Twitter account on 30 November 2016, has been widely published on the Internet, and notably in a Huffington Post article the following day.

It is an obvious concoction from a 2011 photograph. Such compositions are easy to make, and it took me just a few minutes to adapt the same original picture to include the fake Alekhine v Capablanca photograph:’

Hoaxers exploit ignorance, haste, laziness and wishful thinking, which makes the chess world a natural target.

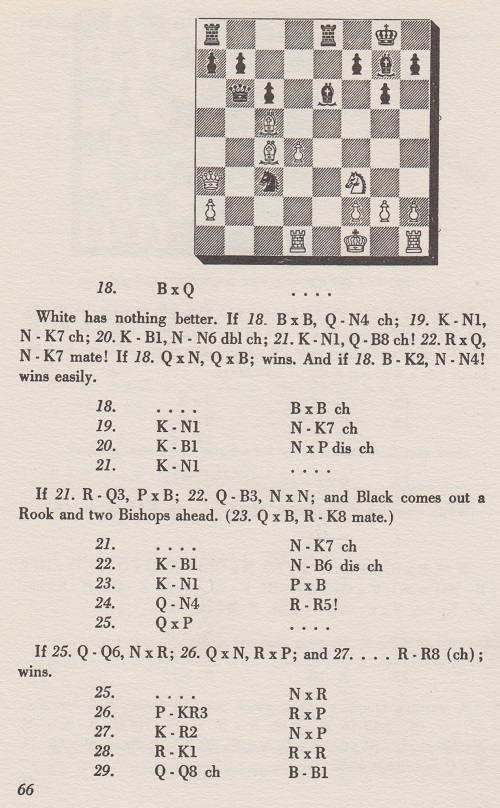

10238. Donald Byrne v Bobby Fischer

In his review of Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games on pages 370-371 of the December 1969 BCM W.H. Cozens mentioned as one of the ‘many surprises’:

‘It does not begin with that “Game of the Century” against Donald Byrne in 1956. The game is not even included in the book.’

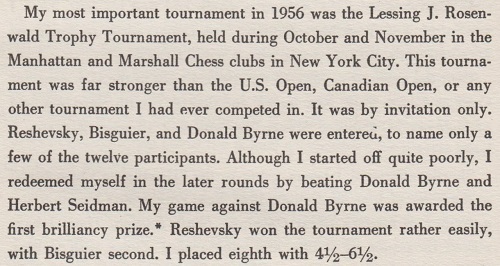

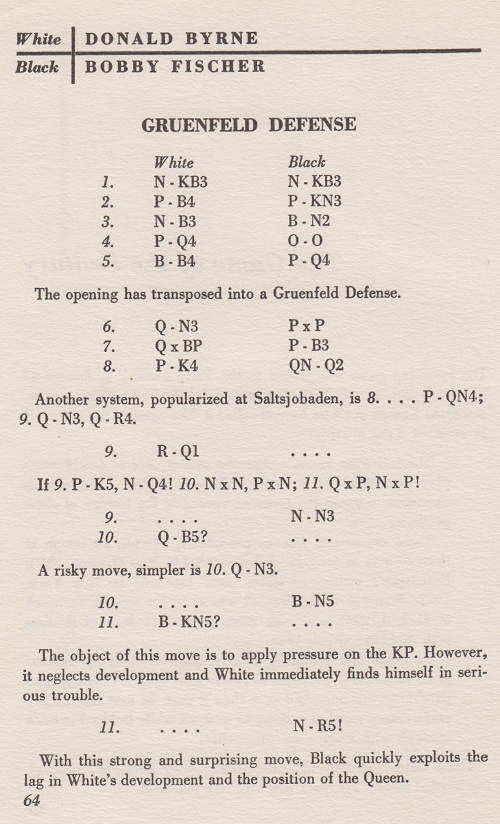

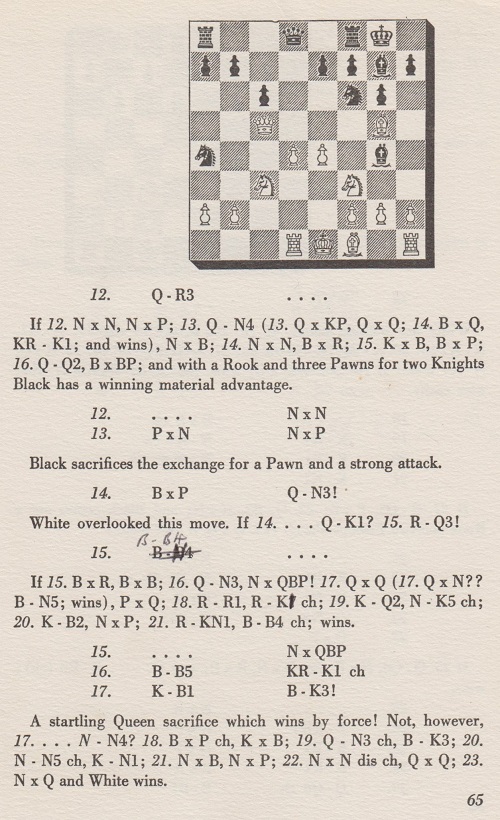

The brilliancy had appeared on pages 64-67 of the future world champion’s 97-page volume Bobby Fischer’s Games of Chess (New York, 1959 and London, 1960):

From the Introduction, on page xiv

Fischer’s statement on page xiv above that the tournament was ‘held during October and November’ is at variance with other sources, including Jack Spence’s book (Omaha, 1958) on the second and third Rosenwald tournaments. Spence recorded that play in the third event ran from 7 to 24 October 1956. Byrne v Fischer occurred in the eighth round, on 17 October (pages 73-75), and that date appears on two versions of the score-sheet in Fischer’s hand. See, for instance, page 63 of My Seven Chess Prodigies by John W. Collins (New York, 1974) and page 170 of A Picture History of Chess by Fred Wilson (New York, 1981).

As regards Lessing J. Rosenwald (1891-1979), below is a photograph from page 44 of the February 1955 Chess Review:

Page 107 of the April 1955 Chess Review had a small picture of Donald Byrne:

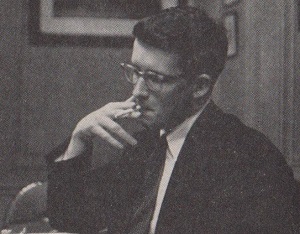

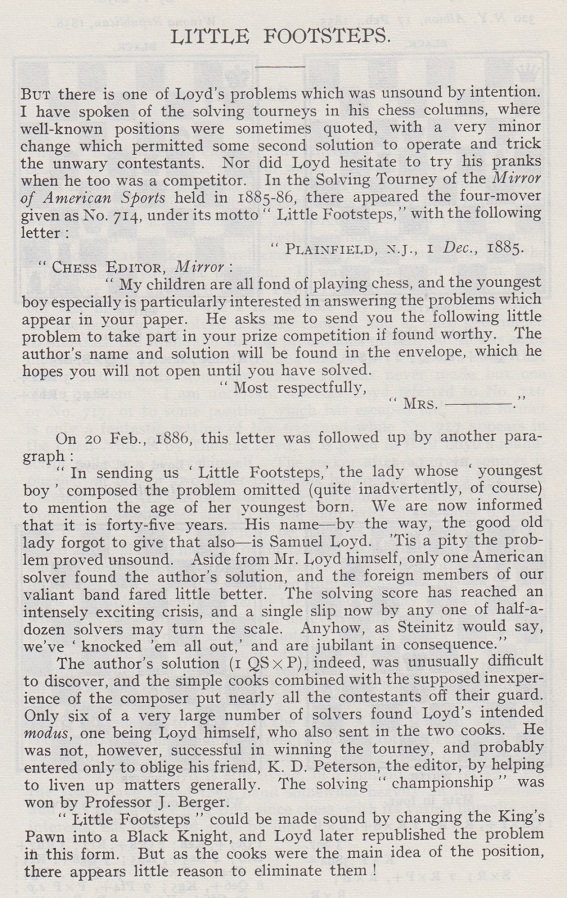

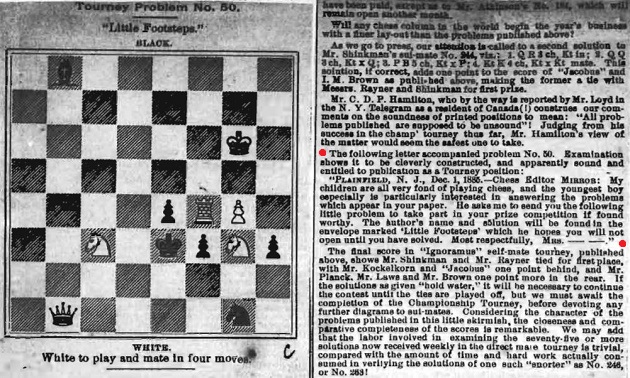

10239. Little Footsteps

Page 53 of the John W. Collins book mentioned in the previous item reported that one of Fischer’s favourite volumes was Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems by Alain C. White (Leeds, 1913). Below is a feature on pages 456-457:

A run of the Mirror of American Sports chess column can be viewed online, in two parts, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, and the cuttings concerning Loyd’s ‘Little Footsteps’ problem are shown below with the Library’s permission.

2 January 1886

20 February 1886

10240. An age conundrum

In a tournament a well-known player won a game against H.E. Atkins, who complimented him on his youthful verve. The player replied:

‘I am so grateful to you, but I do not feel youthful. The day before yesterday I was 51, and next year I shall be 54.’

Who was the player and where did his game against Atkins take place?

10241. A prediction about how Fischer would die

Many people are unaccountably fond of predicting who will win chess matches and tournaments, but a rarer, darker form of prophecy concerns how a player’s life will end. The example that we have in mind is by Joseph Platz (1905-81): his prediction that Bobby Fischer ‘would end his life by suicide or die in an insane asylum’.

In a simultaneous display in 1964 Fischer was defeated by Platz, who annotated the game on pages 4-5 of the Spring 1964 issue of the Connecticut Chess Light. Annoyed that his greatest chess hero, Emanuel Lasker, was omitted from Fischer’s list of the ten greatest masters in an article in the January-February 1964 issue of Chessworld, Platz wrote:

‘My victory over Fischer gave me a double satisfaction in as much as I avenged Dr Lasker, whom Fischer does not even rate among the ten greatest players of all times, and whom Fischer calls a “weak player”. In the name of Lasker I answer, “Indeed for 27 yrs he was a very weak! player”. And I would add: Ask any group of players who was the greatest player of all times and some will say Alekhine, and some will say Lasker. But no-one will give Lasker less than second place.’

After quoting views on Lasker by Réti, Helms, Alekhine (inaccurately, as pointed out in C.N. 138), Fine, Capablanca, Reinfeld and Einstein, Platz concluded:

‘So much about some of the geniuses who paid homage to Lasker, the chessplayer, the mathematician, the philosopher, the writer, the playwright, this unique, this lovable personality.

And now I ask, can anyone say the same about Fischer? Playing chess, he knows that, perhaps better than anyone else, although he has yet to prove it. And how long will he stay at the top? 50 years, like Lasker? And what qualifies him to write chess history and rank players?’

When Platz’s article was reprinted on pages 4-5 of the Connecticut Chess Newsletter, Winter 1978-79, the sentence ‘And what qualifies him to write chess history and rank players?’ was omitted. Moreover, Platz added an afterword:

‘Please note that this was written by me in 1964, eight years before Fischer became World Champion. At that time I predicted that Fischer would become World Champion, that he would keep his title for not more than six years, that he would end his life by suicide or die in an insane asylum.’

From page 5 of the Connecticut Chess Newsletter, Winter 1978-79

The full article in the Connecticut Chess Newsletter was reproduced on pages 44-45 of Chess Horizons, April-May 1979. It was also given on pages 135-137 of Chess Memoirs by Joseph Platz (Coraopolis, 1979), but ‘he would end his life by suicide or die in an insane asylum’ was replaced by ‘he would die like Paul Morphy’.

Concerning Platz’s claim (page 5 of the Connecticut Chess Newsletter, Winter 1978-79) ‘At that time I predicted ...’, the wording could be taken to refer to either 1964 or 1972. As shown above, Platz’s article in the 1964 Connecticut Chess Light made no predictions of any kind, but merely asked rhetorically whether Fischer would, like Lasker, stay at the top for 50 years.

On page 410 of the July 1972 Chess Life & Review Platz was one of a stream of pundits who dispensed opinions on the Reykjavik match. Predicting a final score of 12½-8½, he commented:

‘Fischer’s knowledge of the game, his natural ability, his will to win every game, even when he has no advantage, will carry him to victory. ... Spassky is under greater pressure ... what will happen to him if he loses the match? ... Fischer will fight with confidence; he is under obligation to nobody.’ (Ellipses in the original.)

Can further relevant remarks by Platz about Fischer be found?

Acknowledgement: the two Connecticut chess publications have kindly been provided by the Cleveland Public Library.

10242. Young Taimanov

Vitaliy Yurchenko (Uhta, Komi, Russian Federation) sends this photograph showing Mark Taimanov (seated on the right) from page 256 of the June 1938 issue of Шахматы в СССР:

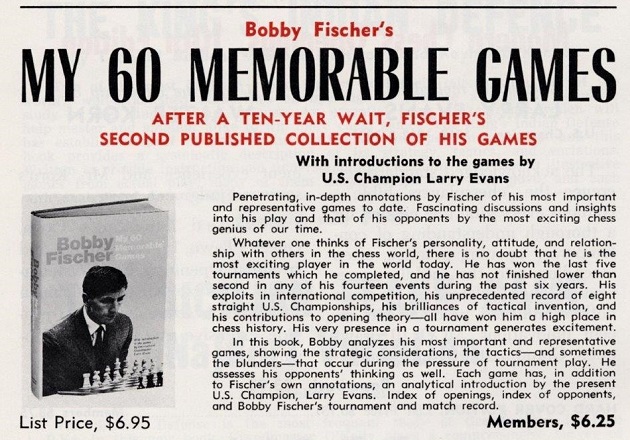

10243. My 60 Memorable Games

From Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England):

‘Towards the end of your feature article Fischer’s Fury you note that My 60 Memorable Games was not mentioned in Chess Review in 1969.

In the 1969 Chess Review catalogue of books and equipment, which was probably issued in late 1968, there was an advertisement for the book on page 20, with the title My Memorable Games. 60 Chess Struggles. It included a mock-up of the dust-jacket:

No mention of the volume was made in the 1969 books and equipment catalogue issued in December 1968 by the United States Chess Federation (the publishers of Chess Life), although its advertisement on page 11 for Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess was illustrated with the photograph used on the dust-jacket of the first Simon & Schuster edition of My 60 Memorable Games. I am not aware that this picture appeared in any edition of Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess.

The 1970 catalogue published by the United States Chess Federation in late 1969, by which time Chess Life and Chess Review had merged, had an advertisement for My 60 Memorable Games on page 14:’

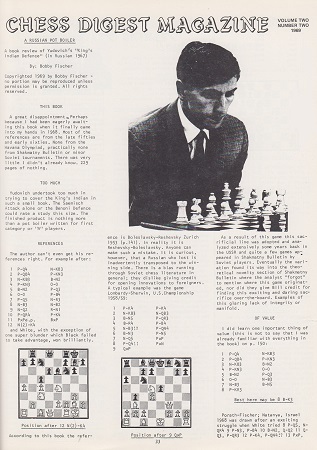

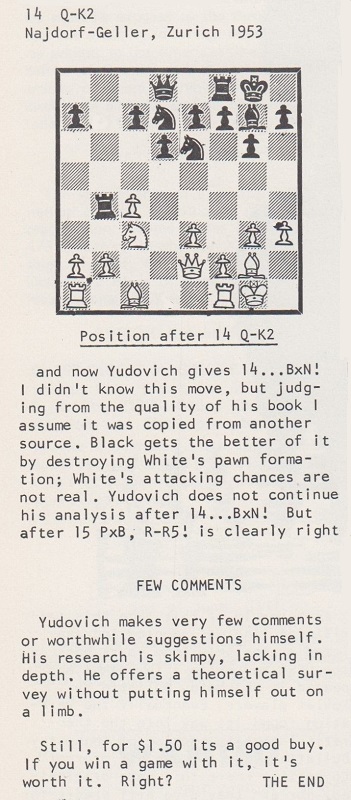

10244. A book review by Fischer

The photograph on the dust-jacket of the original US edition of My 60 Memorable Games also accompanied a review by Fischer of M. Yudovich’s monograph on the King’s Indian Defence (‘229 pages of nothing’) in the 2/1969 Chess Digest Magazine (pages 33-34):

The conclusion on page 34:

10245. An age conundrum (C.N. 10240)

‘I am so grateful to you, but I do not feel youthful. The day before yesterday I was 51, and next year I shall be 54.’

The speaker of these imaginary words was Amos Burn (born on 31 December 1848) after his game against H.E. Atkins in the Craigside tournament in Llandudno on 1 January 1901. (Page 543 of Richard Forster’s monograph on Burn notes that the game-score has not been found.)

There was a small anagrammatic clue with ‘I am so’, and the item was our adaptation of a puzzle (concerning Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson, and with no chess connection) on page 47 of Murder at the Chessboard edited by ‘P.T. Houdunitz’ (New York, 2001).

Chess has only a few mentions in the book, whose title is derived from a simple detective story by Stan Smith on pages 116-119 concerning a game of monochromatic chess.

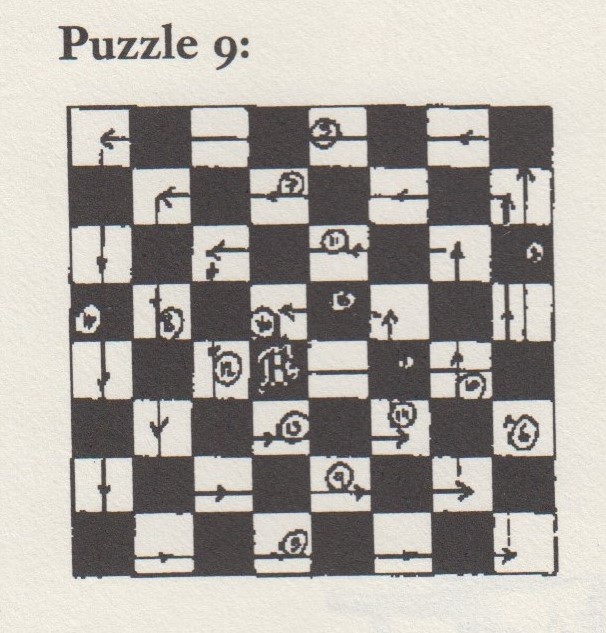

Another of the puzzles interspersed among the short stories has this unhelpful textless solution at the end of the book (page 239):

10246.

Clive James

A remark by Clive James on page 20 of his Introduction to From the Land of Shadows (London, 1982):

‘The necessary conceit of the essayist must be that in writing down what is obvious to him he is not wasting his reader’s time. The value of what he does will depend on the quality of his perception, not on the length of his manuscript. Too many dull books about literature would have been tolerable long essays; too many dull long essays would have been reasonably interesting short ones; too many short essays should have been letters to the editor.’

Such sentiments could readily be expanded to include today’s communication means, where wasting the reader’s time is an infrequent concern.

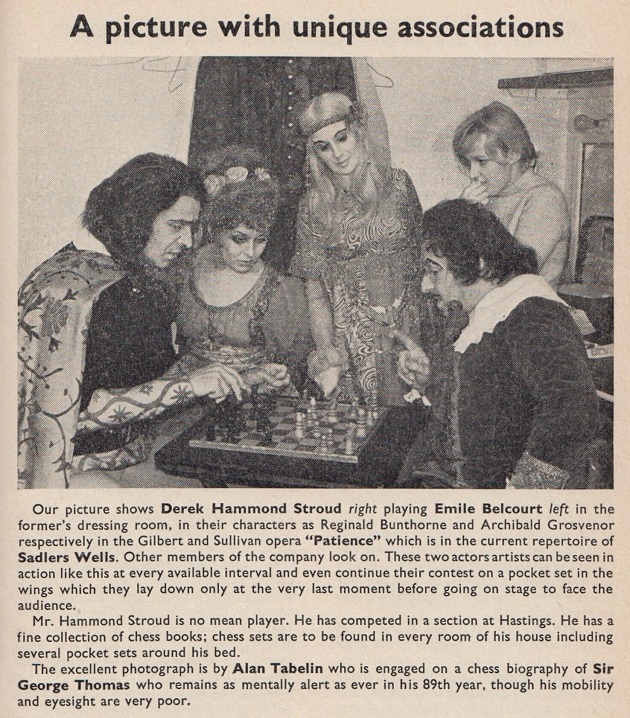

10247. Alan Tabelin and Sir George Thomas

Source: CHESS, Easter 1970, page 225.

Is any information available on Alan Tabelin’s planned book on Sir George Thomas, mentioned in the final paragraph?

10248. Richard Teichmann

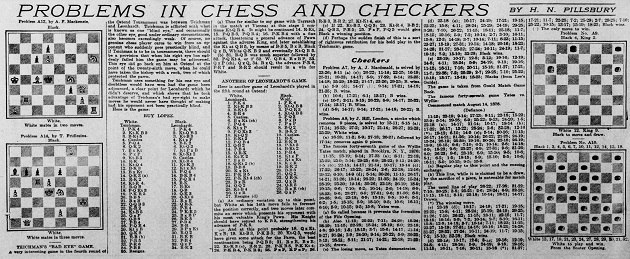

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) notes in holdings of the Jack O’Keefe Project an article by Pillsbury in the Philadelphia Inquirer of 3 September 1905 which discussed Teichmann’s eyesight in connection with the game Teichmann v Leonhardt, Ostend, 16 June 1905.

We add that the column appeared on page 2 of the Comic Section of the Inquirer:

10249. Resignation (C.N. 10233)

Frits Fritschy (Leiden, the Netherlands) comments that A. Soltis’ attempt (copied by L. Evans) to give the Dutch term relating to resignation was also faulty, since geef het op is the imperative form. Standard Dutch usage is either the past participle opgegeven or Wit geeft het op/Zwart geeft het op.

We add that elsewhere on page 57 of the Soltis book referred to in C.N. 10233 German tenses were muddled: ‘... and Spielmann got a chance to “aufgegeben”.’

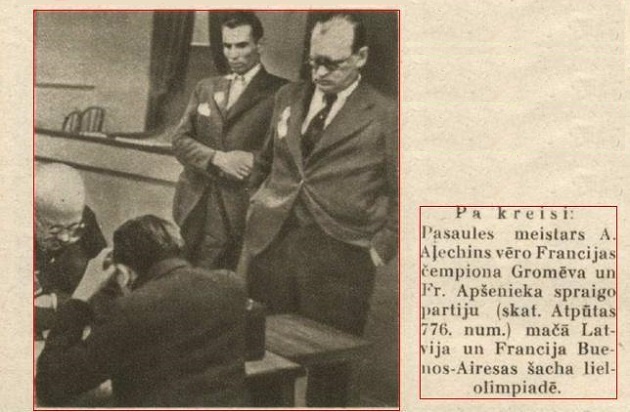

10250. Alekhine at the 1939 Olympiad in Buenos Aires

From Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) comes this photograph published on page 27 of Atpūta, 8 December 1939:

10251. Draws and scoring systems (C.N. 6671)

In a letter on page 441 of CHESS, 20 August 1955 P.N. Wallis of Quorn referred to ‘dull and unenterprising chess which is prevalent in this country’, adding:

‘The remedy is quite simple. In the British Championship and similar tournaments let a win count 3 points and a draw one to each player, thus putting a premium on the win.’

On page 454 of the 30 September 1955 issue, R.W. Ives of Leeds responded:

‘Mr Wallis raises an old issue. James Mason in 1895 advocated allowances of 1, 0 and minus a half for a win, a draw and a loss respectively, and this seems to me mathematically more logical than the present system. Certainly it seems now that quite a few halves can be picked up in a congress without much thinking. Why should a pre-arranged draw improve either player’s score? The position should be the same as before they started. A player who has lost has a worse record after the game than when it started. Can your readers work it out?’

Writing from Belfast, A.S. Russell commented in CHESS, 15 October 1955:

‘Mr P.N. Wallis proposes that a draw should count only one-third as much as a win. This is intended to penalize the player who adopts stodgy drawing variations. To me it seems that it might have the opposite effect.

Suppose an enterprising player meets a draw-minded opponent, he is faced with a difficult problem. If he ventures on risky play to avoid a draw ... he runs great danger of losing and handing an easy three points to the very type of player Mr Wallis wants to penalize.

The solid player would not now plod along half-way down the table but would bound ahead, aided by bonus points gained against desperate opponents risking too much to avoid the penalizing draw.’

A contribution from C.J.S. Purdy of Sydney was published on page 93 of the 10 December 1955 issue:

‘R.W. Ives (CHESS, 30 September) did not realize that James Mason’s proposal to award 1,0 and minus a half for a win, draw and loss respectively is mathematically exactly the same as P.N. Wallis’s proposal to count a draw as worth one third of a win. This is easily seen if you add a half to every player’s score in every game, irrespective of his result (this cannot affect the positions). You then get 1½, ½, 0; or, eliminating fractions, 3, 1, 0, which is Mr Wallis’s system. Less drastic, of course, would be 5, 2, 0. Mathematically, there is no objection whatever to penalizing draws.

In CHESS of 15 October, A.S. Russell raises an objection which is much less weighty than many players imagine. His objection is that by deliberately playing “stodgy drawing variations” players can induce strong opponents to play wildly and thus lose. The old bogey that it is a great handicap to meet an opponent who plays deliberately for a draw, and that one has to play mad gambits to circumvent him, dies hard. Botvinnik, when three points up against Smyslov, could have won the match easily had there been anything in this theory. It “cuts both ways”. The draw-monger will fail to make the most of his position, and thus give his opponent chances to gain ground, e.g. Capablanca against Lasker at St Petersburg, 1914, where Capablanca played “drawishly” instead of seeking to exploit his two bishops aggressively, and lost. I see no objection to one player trying to draw – only to both players trying to draw. Penalizing draws would certainly eliminate that. Admittedly, many draws are genuine, and it is a drawback that all would be equally penalized. But not as great an evil as arranged draws, which give some players extra rest days. These draws are not merely “drab”. They are cheating.’

W. Heidenfeld of Johannesburg replied on pages 153-154 of

CHESS, 11 February 1956:

‘In your “drab draws” correspondence C.J.S. Purdy writes: “Admittedly, many draws are genuine, and it is a drawback that all would be equally penalized. But not as great an evil as arranged draws, which give some players extra rest days.” It is hard to believe that your correspondent is serious in his suggestion that draws of whatever nature should be “penalized”, seeing that chess – like cricket – is a game that allows for a very wide drawing margin; a game that regards players as equal who are merely “approximately equal” and that does not insist that differences of split seconds or fractions of inches in performance are to be rewarded by plus and minus signs. In athletics “draws” are few and far between; in tennis they do not exist at all; and it would have been simple enough to have chess decided on similar lines.

It is clearly illogical not to object to one player trying to draw, but to object to both players trying to draw – if the draw serves the purpose of both. Playing in a tournament, your object is not to win the game – any game – but to win the tournament; and where playing for a win at all cost does not conform to this aim, even the temptation to do so must be firmly resisted. In fact, the ability to resist this temptation is part of a successful player’s technique. Some of the most glorious strokes of cricket may have to remain unplayed – some of the most imaginative games of chess to remain unconceived – because the player has the will to win ... the match or the tournament. In other words, it is exactly the will to win that may dictate to you the necessity of drawing an individual game. Players who do not possess this will to win may indulge their fancy at leisure – but they hardly deserve to get an extra bonus for it.

Leaving aside the special case of the “drab” draw, I believe that masters and annotators have a lot to answer for the [sic] general contempt of “drawn games”. It does not suit their book to annotate such games – because obviously it is far more difficult to assess a good fighting draw correctly than it is to come to definite conclusions regarding the merits of a won and lost game. In the latter, the fact that one side lost is in itself a clear indication of some inferior moves somewhere or another. But in a drawn game – did White stand to win? Did Black? Or was what Lasker called the Remisbreite never exceeded all through the game?

Looking at draws without passion or emotion, one must surely realize that they are the best chess games of all. The best draws must be better games than the best wins – neither side made a mistake sufficiently serious to enable the other, even with best play, to swing the balance in his favour. Yet how many anthologies of famous games have such draws? Games like Alekhine v Réti, Vienna, 1922 or Alekhine v Marshall, New York, 1924? At best very short games of this nature, like the famous draw between Pillsbury and Halprin at Munich, 1900, or the equally famous first encounter between Botvinnik and Alekhine at Nottingham, 1936, are “tolerated”.

If, in such games, the defender had been a little less alert, had lost his way, no matter how slightly, just once, they would rank among the very best specimens of fighting chess. And because the defence was perfect they don’t? Is this the famed chess players’ logic?

I am at present working on the MS of a book “Battle in the balance”, a collection of the finest draws of modern chess, from Hamppe v Meitner, 1872 to Schmid v Castaldi, Venice, 1953. During these 80 years some 50 to 60 practically perfect games of chess were played –and the great majority of them are almost completely unknown.’

Concerning Heidenfeld’s eventual book, Grosse Remispartien (Düsseldorf, 1968), see C.N. 7049. Two paragraphs from the Introduction to the English edition, Draw! (London, 1982), are quoted in Chess Jottings.

The references above to James Mason’s proposal in 1895 concern the extensive correspondence (also involving E.N. Frankenstein and W. Sonneborn) published in the BCM that year and in 1896. However, Mason had made his proposal in a letter (London, 10 December 1892) on pages 40-43 of the January 1893 BCM. On page 42 he wrote:

‘A win should count 1, a draw 0, and a loss minus ½ only, it being in reality no more. It takes two to make a game. What any player loses in losing any particular game is not the whole of that game, but only his own individual half of it, or his chance of winning it. The game counts 1 to the winner; that 1 is made up of twice ½ – his own ½ and his opponent’s ½ – only one of which is, strictly speaking, either won or lost. In fine, the system here proposed is a natural system, and the only one which can be substituted for the present system with advantage to all concerned. It would encourage every player in a tournament to do his best to win, the draw being valueless for scoring purposes.’

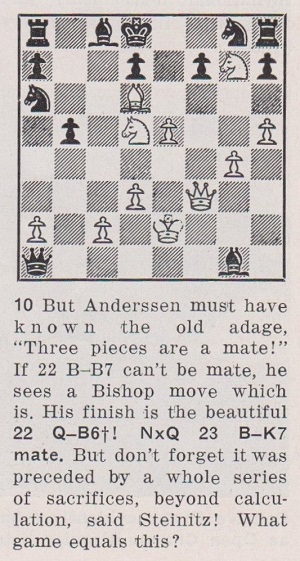

10252. ‘Three pieces are a mate’

The final diagram in the presentation of the Immortal Game between Anderssen and Kieseritzky on page 297 of the October 1959 Chess Review:

The literal implication that the adage ‘three pieces are a mate’ pre-dated 1851 can be discarded, but who first made the observation?

On page 28 of The Seven Deadly Chess Sins (London, 2000) J. Rowson described ‘three pieces is a mate’ as ‘Tartakower’s claim’. On page 606 of Chess Life & Review, November 1970 A. Soltis wrote, ‘... as Tartakower said, “three pieces are a mate”.’

Introducing a correspondence game between Krozel and Thompson on page 224 of the July 1955 Chess Review John W. Collins wrote: ‘A short game which further demonstrates that three pieces are a mate.’ An editorial footnote on page 369 of the December 1964 issue stated: ‘As the late Henry Eckstrom would have said: “Three pieces are a mate”.’

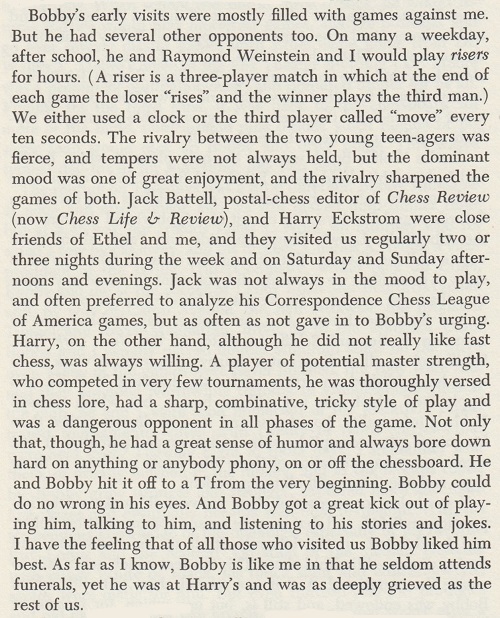

10253. Henry/Harry Eckstrom

Readers are invited to provide information about H.E. Eckstrom, who was mentioned in the previous item.

His name appeared several times in My Seven Chess Prodigies by John W. Collins (New York, 1974), and page 40 recorded that Eckstrom’s was one of the few funerals attended by Fischer:

Eckstrom’s final appearance in the postal ratings published in Chess Review was in 1964. Page 163 of the June 1959 issue referred to him as ‘Henry E. Eckstrom of Brooklyn’, and the following year (January 1960, page 3) the magazine quoted a remark by ‘that wily kibitzer Harry Eckstrom.’

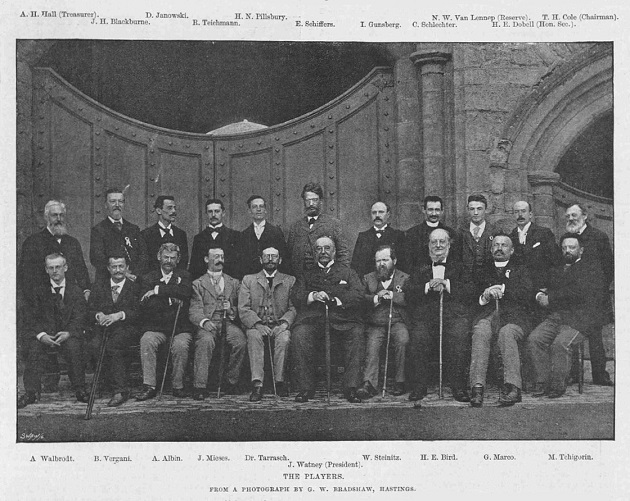

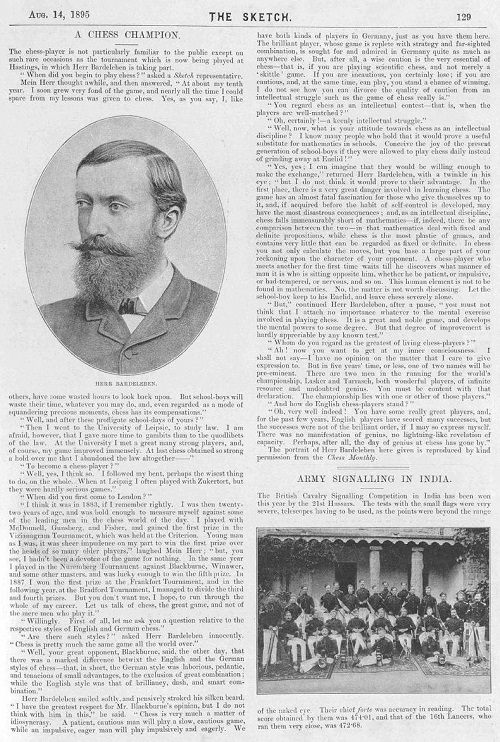

10254. Hastings, 1895 (C.N. 7354)

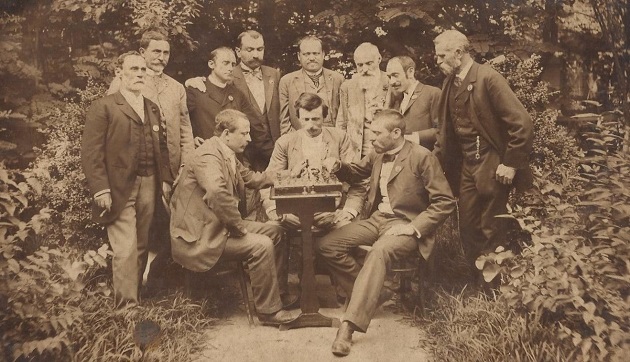

C.N. 7354 asked whether it was possible to show a higher-resolution copy of a photograph found by a correspondent on page 221 of The Sketch, 21 August 1895. It can now be provided:

10255. Gordon of Cluny vs the Duke of Mortemart, 1721

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘State papers in the National Archives contain a description of a short chess match played in 1721. A report was submitted by Thomas Crawfurd, a representative in Paris of the British Government, to Lord Carteret. The second part of Crawfurd’s letter is dated Paris, 27 September 1721 and includes the passage below (source: National Archives, SP 78/170, folios 258-259). The French in the original text is archaic and contains unusual spelling throughout, including vagaries such as “a platte couteur”, “Mortimar” and “Pentenidder”. It is a good-quality original, with legible handwriting, and my transcript is faithful to it, retaining the oddities:

“Votre Exce me permettra d’ajouter une petite nouvelle qui fera plaisir (je crois) a My Lord Sunderland. Aujourdhuy le Duc de Mortimar fameux Champion aux echecs pour la Nation française a eté battu a platte couteur par Mr Gordon de Cluny un Ecossais qui est bien connu a My Lord Sunderland et a eu l’honneur de jouer contre luy. Gordon est icy attendant le sort du papier qu’il a acheté avec son argent, et il y a long temps que Mr de Mortimar ayant ouy parlé de luy me fit prier par plusieures personnes de lier une partie avec le dit Gordon pour jouer aux echecs contre luy, mais Gordon a eté jusques a depuis peu si chagrin de ses pertes qu’il n’a pas voulu s’y engager, a la fin je l’ay persuadé d’accepter le defy et mardi dernier a la Cour j’ay donné rendezvous a Mr de Mortimar pour aujourdhuy chez Mr de Pentenidder qui nous a prier a diner a la Campagne avec une nombreuse compagnie. Le Roi P: C:, qui joue aussi aux echecs, et toute la Cour en a eté avertie. Les Combattans ont jouéz 4 parties dont Mr Gordon a gagner 3. La derniere a eté un refait par une grosse meprise que Mr Gordon fit vers la fin de la partie. Mr de Mortimar a eté un peu picqué de sa deroutte, et pour sa plus grande mortification, estant presentement en fonction comme Gentilhomme de la Chambre, il a eté obligé de partir sur le champs pour se trouver au soupé du Roy ou il fallait en rendre conte. Il ne se tient pas encore pourtant pour moins habile que Mr Gordon et attribue la perte des trois premieres parties a ne s’etre pas encore fait a la maniere de jouer de Mr Gordon il a meme offert de trouver de parieurs de son coté, pourveuque Mr Gordon en pouvait trouver du sien, ce que je crois ne luy sera pas difficile ainsi il y apparence que cette partie fera encore plus de bruit.”

In summary, Crawfurd reports that the Duke of Mortemart, described as the French national chess champion, was comprehensively beaten by Mr Gordon of Cluny, a Scotsman who is well known to Lord Sunderland, against whom he has played. The encounter was arranged by Crawfurd at Mortemart’s request and took place at the country residence of M. de Pentenrieder, in the company of many guests. The King, who also plays chess, and the entire Court, was informed of it. Of four games played, Gordon won three, and the last was a draw after a blunder by Gordon. To add to Mortemart’s mortification, his position of Gentleman of the Bedchamber obliged him to leave in order to attend the King’s supper, where the story had to be told. He does not consider himself less skilful than Gordon and attributes the loss of the three games to not yet being accustomed to Gordon’s style of play. He has suggested a match with backers on each side, so there is the prospect of further play.

John Finlay, on pages 19-20 of The Community of the College of Justice: Edinburgh and the Court of Session, 1687-1808 (Edinburgh, 2012), noted that Robert Gordon of Cluny, an advocate, who was sent to France in 1719 by his relative Sir William Gordon to invest some of the latter’s money in French stocks, ...

“... spent some time playing chess among the foreign ministers resident in Paris.”

In The Gordons of Cluny (privately printed, 1911), John Malcolm Bullock mentioned, on page 6, a Robert Gordon of Cluny, who died in April 1729 and was a nephew of Kenneth Gordon, an advocate. The death was reported on page 1 of the Daily Post, 15 April 1729:

“Edinburgh, 7 April. On Saturday last died the Learned Mr Robert Gordon of Cluny, Advocate, in the 40th Year of his Age, a Gentleman of great Integrity and Honour, much esteemed and beloved by all the Lovers of Learning.”

The Duke de Mortemart in 1721 was Louis de Rochechouart (1681-1746). Richard Twiss mentioned the Duke de Mortemart on page 165 of his book Chess (London, 1787) in the course of some remarks about a somewhat later period of French chess history:

“Of the second-rate players who were able to defend themselves against Mr de Legalle, with the advantage of the pawn and the move, were the Chancellor d’Aguesseau and his son; the President de Nicolai, the Duke de Mortemart, the Duke de Mirepoix, the Abbé Chenard, the Abbé Maillot, Mr Foubert, and Mr de St Paul.”’

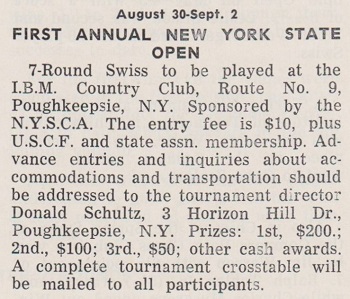

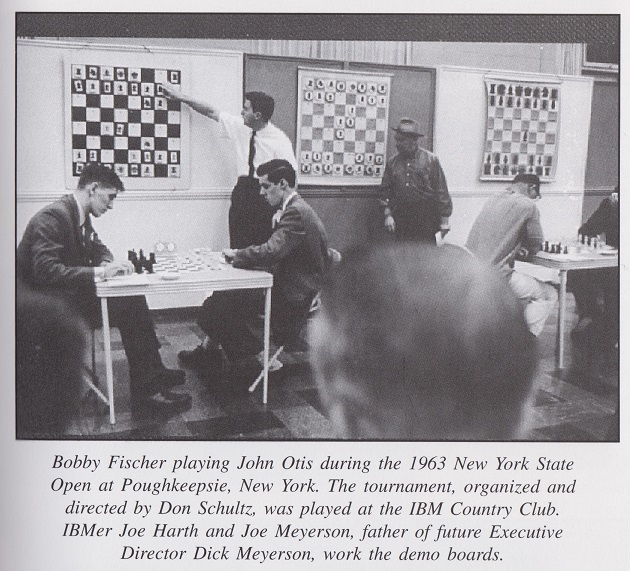

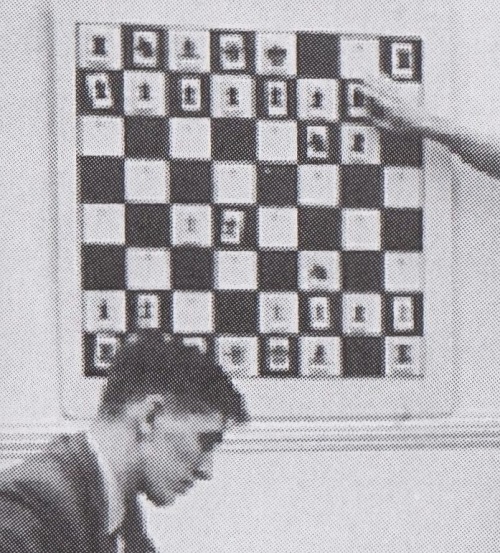

10256. Bobby Fischer at Poughskeepie, 1963

From John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA):

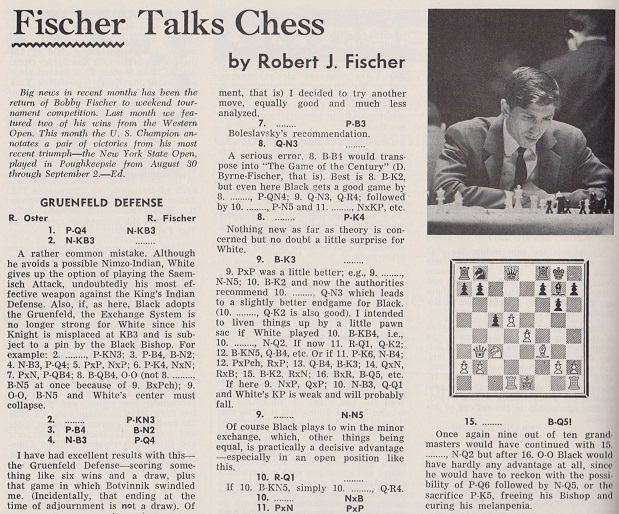

‘The last Swiss System tournament of Bobby Fischer’s career was the New York State Open in Poughskeepie in 1963, an event which was poorly covered in American magazines of the time with the exception of Chess Life. Fischer annotated four of his seven games (against R. Oster, B. Greenwald, L.W. Beach and A. Bisguier) in Chess Life, and his notes to the Bisguier game were reworked for My 60 Memorable Games (game 45), where a fragment from another game in the event, against Miro Radojčić, was added. Fischer’s remaining games, against Matthew Green and Joseph Richman, are also known.

No tournament bulletin was issued, and the crosstable has not been published, even though the pre-event advertising announced that all participants would receive one by mail (e.g. on page 202 of the July-August 1963 Chess Life):

It is thus difficult to resolve a mystery stemming from a photograph opposite page 208 of Chessdon by Donald Schultz (Boca Raton, 1999):

Schultz gave the same photograph, with a similar caption, on page 17 of Fischer, Kasparov, and the Others (Highland Beach, 2004), writing there too that Fischer was facing John Otis. However, Otis is not listed as an opponent of Fischer’s in the tournament. Moreover, the board position is the same as at the beginning of the game which Fischer annotated on pages 236-237 of the October 1963 Chess Life (mentioned in C.N. 4423), where he gave his opponent’s name as R. Oster.

Can Fischer’s opponent in the Poughkeepsie photograph be positively identified?’

10257. An interview with Curt von Bardeleben

This interview with C. von Bardeleben on page 129 of The Sketch, 14 August 1895 was published three days before his loss to Steinitz in the Hastings tournament:

10258. du Mont

How an anecdotarian may milk an ‘episode’:

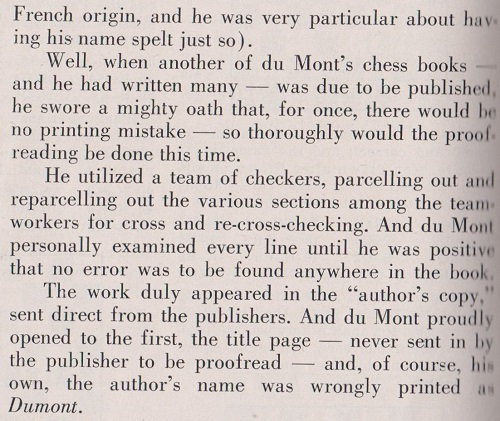

The writer was Walter Korn, on page 18 of Chess Review, January 1959. J. du Mont’s forename was Julius, not James. Variants on later writers’ spelling of his surname were shown in C.N. 8827, but we recall no book of du Mont’s which had ‘Dumont’ on the title page. There was, though, ‘Du Mont’ in The Basis of Combination in Chess (London, 1938):

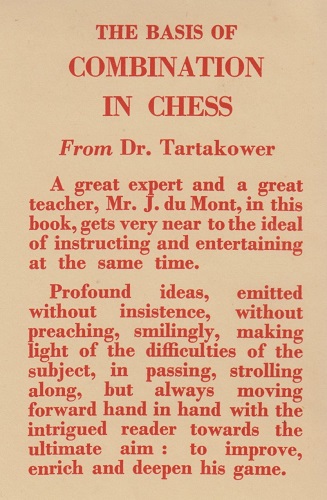

The dust-jacket had the correct spelling du Mont, e.g. in the praise from Tartakower quoted in C.N. 4441:

A book inscribed by du Mont was shown in C.N. 5397, and another one in our collection is 200 Miniature Games of Chess (London, 1941):

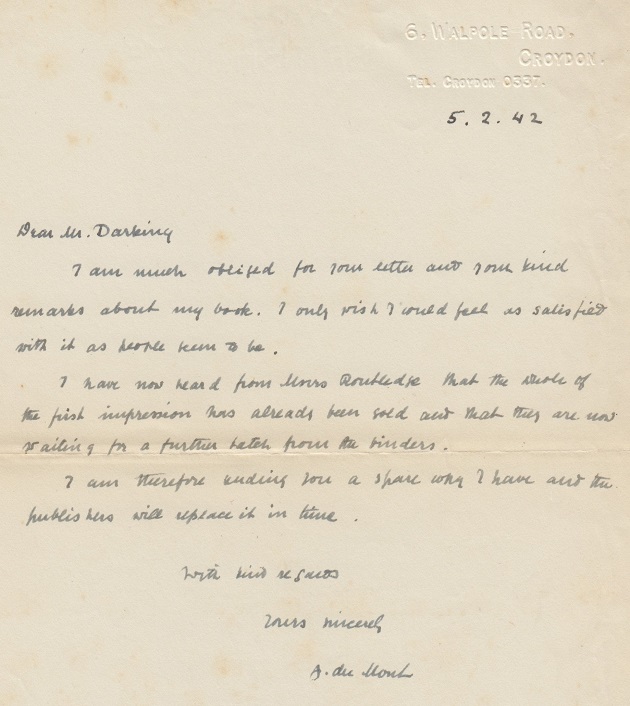

In that copy is a letter written by du Mont on 5 February 1942:

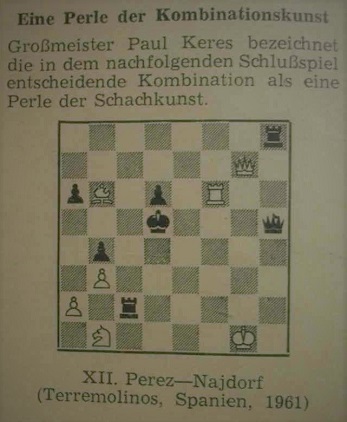

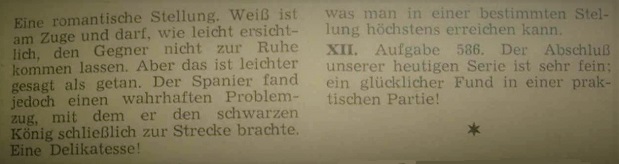

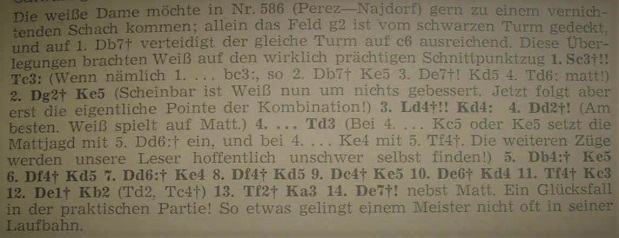

10259. Pérez v Najdorf, Torremolinos, 1961 (C.N. 10223)

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) notes Kurt Richter’s treatment of the Pérez v Najdorf position on pages 312-313 of the 20/1961 issue of Schach (the second October issue):

The solution was given on page 327 of issue 21/1961 of the German magazine (the first November issue):

Our correspondent mentions that the texts are almost identical to what appeared on pages 47 and 224 of Schönheit der Kombination (East Berlin, 1972). In the diagram caption both sources had the spelling ‘Terremolinos’.

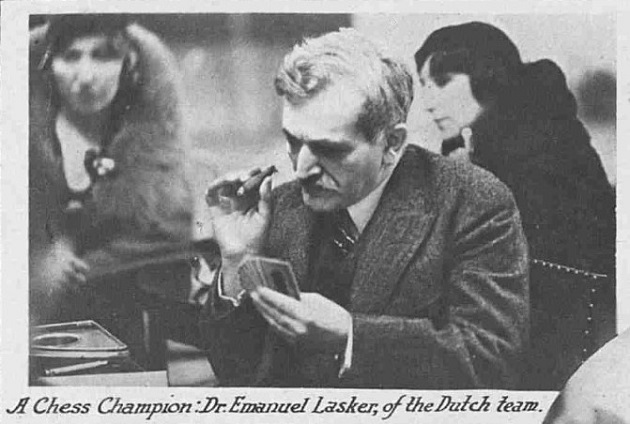

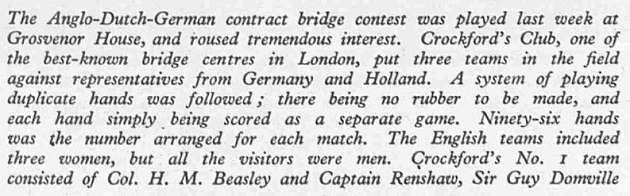

10260. Lasker playing bridge

An addition to Chess and Bridge from The Sketch, 3 February 1932, page 195:

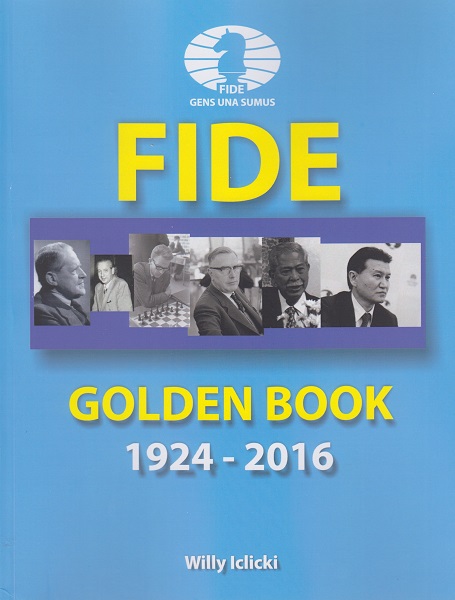

10261. FIDE awards

When FIDE Golden book 1924-2002 by Willy Iclicki was discussed in C.N. 3157 (see pages 117-118 of Chess Facts and Fables and Chess Awards) we made frequent use of ‘sic’ in view of the many typos: ‘H.E. Francis [sic] Chiluba, President of the Repulic [sic] of Zambia’; ‘Ernesto Che Guevarra [sic]. Post Humous [sic] Award, Cuba’; ‘Commender [sic] of the Legion of Grandmasters’; ‘Grand Commender [sic] of the Legion of Grandmasters’; ‘H.E. Aslan Abashidze, Chairman Supreme Council of Adjarian Rupublic [sic] of Georgia’; ‘Lenox [sic] Lewis, World Heavyweight Boxing Champion, England’; ‘Pierre Sisman [sic], President of Disney Consumer Product [sic] S.A., France’.

An updated edition of the Golden book (covering 1924 to 2016) has just been produced by Mr Iclicki. On pages 22-23 all the above errors remain.

The sole good news is that no new names have been added

to any of the lists of ‘Special Awardees’, the categories

being ‘Grand Commender of the Legion of Grandmasters’,

‘Commender of the Legion of Grandmasters’, ‘Grand Knight

of FIDE’, ‘Knight of FIDE’ and ‘Most Esteemed Friends of

FIDE’.

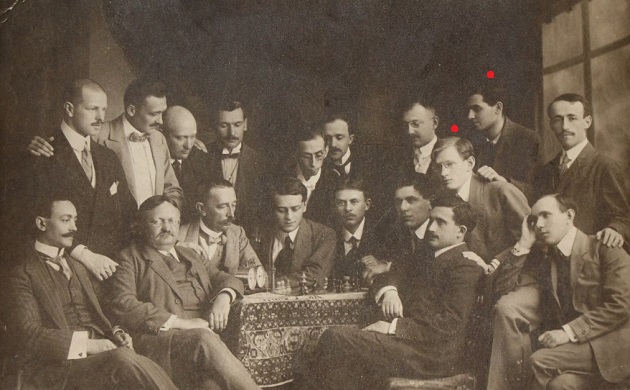

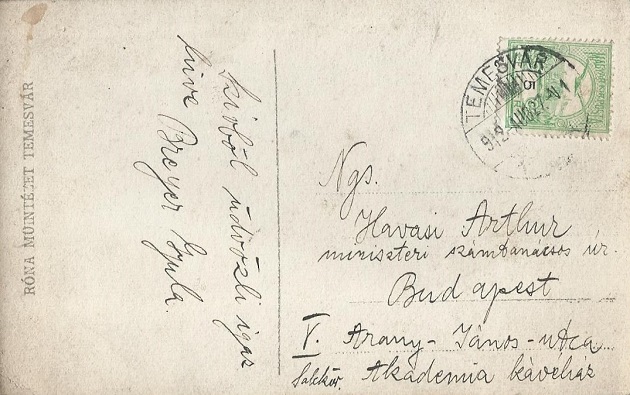

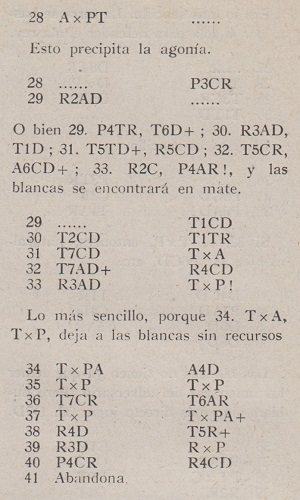

10262. Hungarian photographs

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) reports that he recently acquired a number of photographs from a Hungarian dealer:

On the first photograph (a postcard signed by Breyer) we have indicated Breyer and Réti. A full caption appeared in volume three of Magyar Sakktörténet by G. Barcza and A. Földeák and in Kis Magyar Sakktörténet by I. Bottlik (published in 1989 and 2004 respectively). Assistance with identifying individuals in the final two pictures will be appreciated. In the last one, Breyer appears to be standing third from the left, Maróczy being seated in the centre.

10263. Copying and incompetence

Another example of the dictum (C.N. 9452) ‘Copying usually goes hand-in-hand with incompetence’ comes from a new Czech edition of Alekhine’s book about his road to the world championship, Na cestě k nejvyšším šachovým cílům, published by Galerie Dolmen (‘Antonín Čížek, 2016’). Images of ours have been used without permission, whereas page 248 has the fake Alekhine-Capablanca photograph.

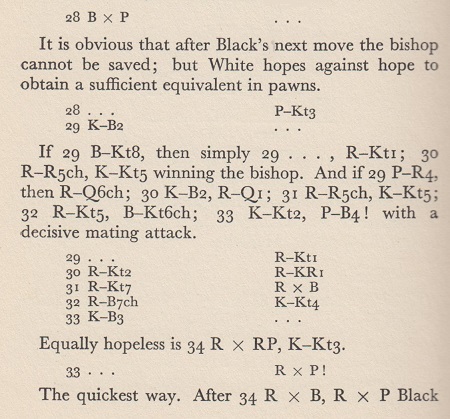

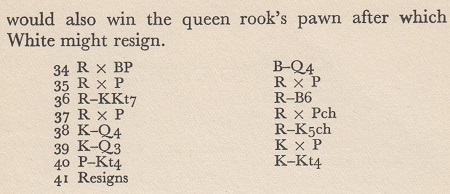

10264. 28 Bxh7

A fragment to which reference will be made in the 29...Bxh2 section of the feature article Spassky v Fischer, Reykjavik, 1972 concerns the position after 27...Bb5-c4 in the 30th match-game (also described as the fifth exhibition game) between Alekhine and Euwe, Rotterdam, 16 December 1937:

Alekhine now played 28 Bxh7. Below is the remainder of the game as annotated by Euwe on pages 200-201 of Alekhine’s match book:

The annotations by Alekhine on page 104 of his book ¡Legado! (Madrid, 1946):

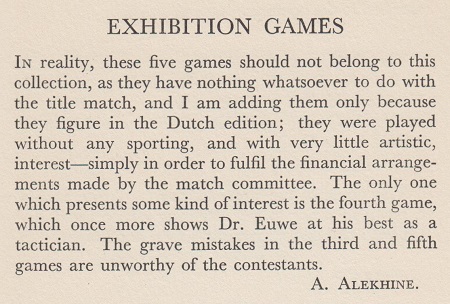

Finally, Alekhine’s remarks about the five exhibition games, from page 183 of his match book:

10265. Rudolf Spielmann and the King’s Gambit

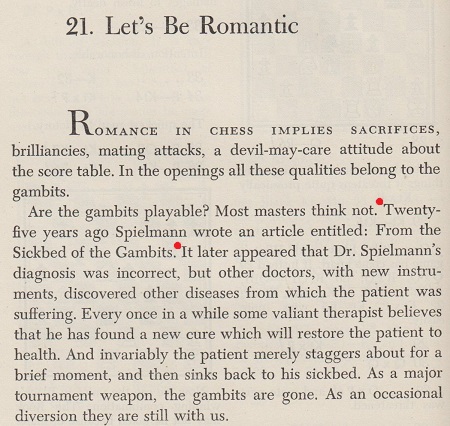

From page 136 of The World’s a Chessboard by Reuben Fine (Philadelphia, 1948):

Next, a line from a column by Robert Byrne in the New York Times, 8 October 2000:

‘In the 1930s, the great champion of the gambit, Rudolph [sic] Spielmann, wrote an article titled, “From the Sickbed of the King's Gambit”.’

On page 171 of Impact of Genius (Seattle, 1992) R.E. Fauber indicated that Spielmann’s article was written in 1926.

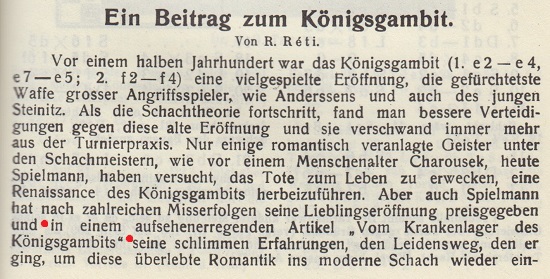

Many writers have referred to the article without any sign of having read it, and the date of its appearance is not altogether straightforward. If, as sources state, it was published in the July-September 1924 issue Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, how could Réti have mentioned it at the start of an article on pages 317-320 of the December 1923 Wiener Schachzeitung?

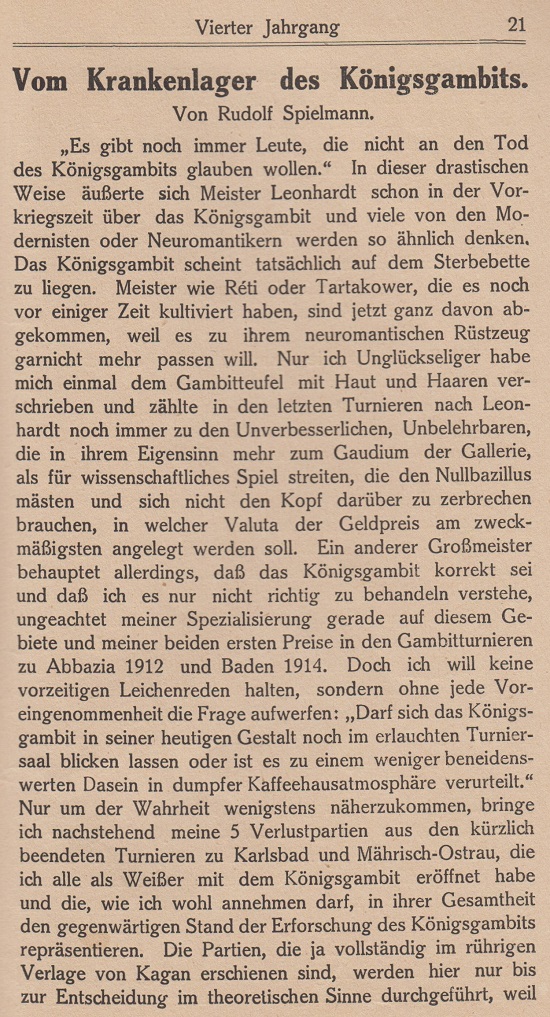

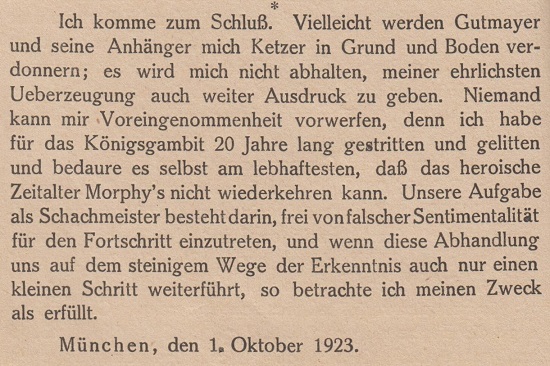

The answer is that the publication schedule of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten was even more erratic than usual, and the July-September 1924 issue comprised games and articles from 1923. Spielmann’s ‘Vom Krankenlager des Königsgambits’ appeared on pages 21-36. The first page and the conclusion are shown below, and it will be seen that the article was dated 1 October 1923.

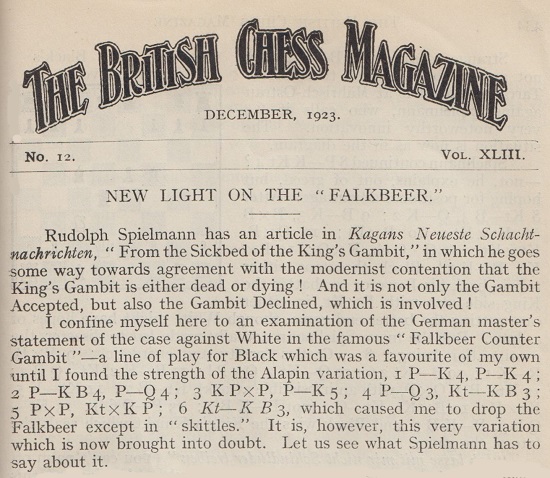

Under the title ‘New Light on the “Falkbeer”’, P.W. Sergeant discussed Spielmann’s ‘From the Sickbed of the King’s Gambit’ article on pages 433-434 of the December 1923 BCM. The magazine had two follow-up articles (January 1924, pages 1-2, and February 1924, page 59).

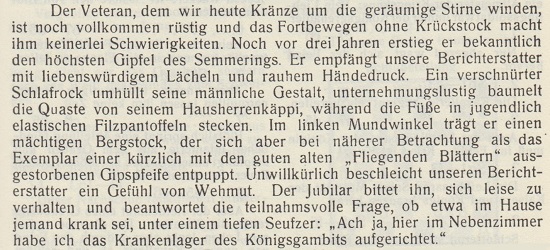

The theme was also taken up in a spoof article ‘Spielmann 46 Jahre alt!!’ on pages 35-37 of the February 1929 Wiener Schachzeitung:

A related matter is the term, ostensibly coined by Tartakower, ‘The Last Knight of the King’s Gambit’ to describe Spielmann. As shown below, the nickname appeared in J. du Mont’s obituary of Spielmann on page 10 of the January 1943 BCM, but how far back can it be traced?

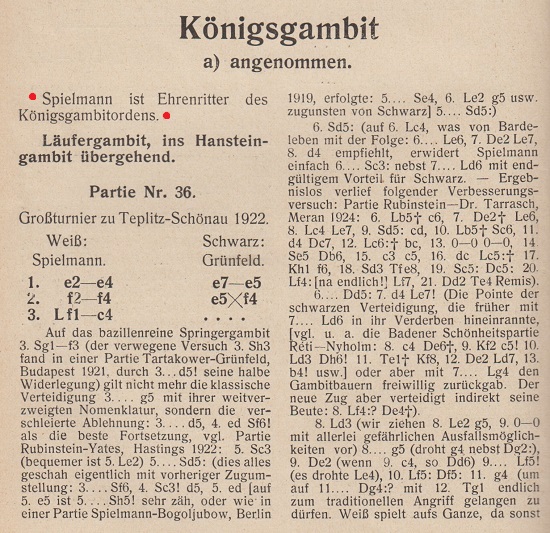

The heading in the King’s Gambit section on page 212 of Tartakower’s Die hypermoderne Schachpartie (Vienna, 1924) had ‘Spielmann ist Ehrenritter des Königsgambitordens’ (‘Spielmann is an honorary knight of the King’s Gambit Order’):

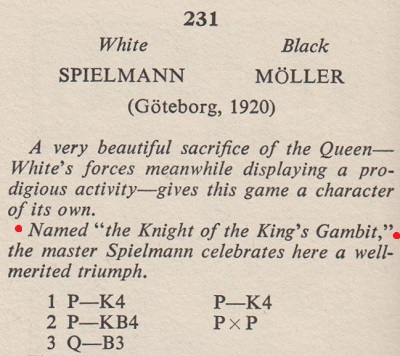

The introduction to a game on page 296 of book one of 500 Master Games of Chess by Tartakower and du Mont (London, 1952) referred to ‘the Knight of the King’s Gambit’:

The word ‘last’ is absent.

This leads to the question of whether it is really a coincidence that Réti wrote similarly, but with the word ‘last’, in the section on Spielmann on page 236 of Die Meister des Schachbretts (Mährisch-Ostrau, 1930):

‘Spielmann ist der letzte Barde des Gambitspiels und wollte insbesonders das Königsgambit zu neuem Leben erwecken.’

In the English edition, Masters of the Chess Board (London, 1933), the translation (page 127) was:

‘Spielmann is the last bard of the Gambit Game, and what he wanted to revive especially was the King’s Gambit.’

Regarding ‘The Last Knight of the King’s Gambit’, two tentative conclusions thus seem possible: either Tartakower used that full term in a text which has yet to be traced or the description resulted from a mistake (by du Mont or by an earlier writer) which combined remarks on Spielmann by Tartakower and Réti.

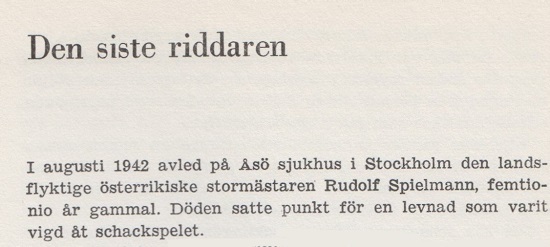

In any case, ‘The Last Knight’ became attached to Spielmann’s name. It was, for example, the title of a chapter about him on pages 60-64 of Strövtåg i schackvärlden by G. Ståhlberg (Skara, 1965):

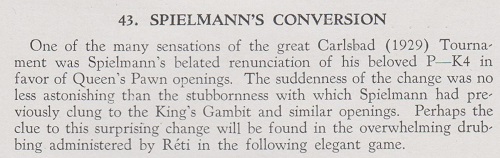

As is well known, in the late 1920s Spielmann began opening with 1 d4 far more often than previously. From page 85 of Chess Strategy and Tactics by F. Reinfeld and I. Chernev (New York, 1933):

The game was Réti’s victory in 31 moves at Trenčianske Teplice, 1928.

In conclusion, though, the following may be noted from page 80 of Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929), in the section on Spielmann:

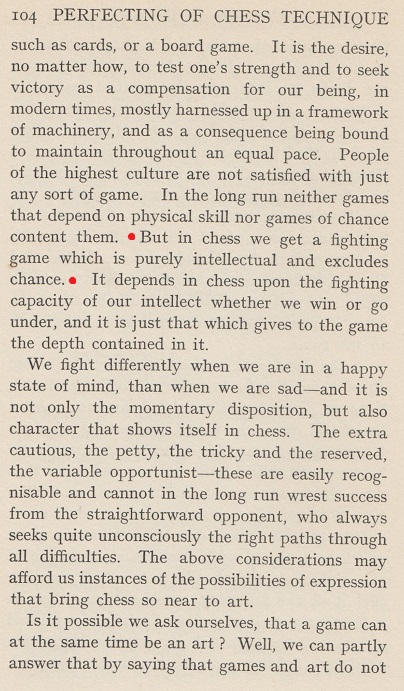

10266. Chance

‘Chess is a fighting game which is purely intellectual and includes chance.’

Anyone who searches on the Internet for that exact wording (attributed to Richard Réti) will find innumerable occurrences, but what Réti wrote was the opposite – ‘excludes’ and not ‘includes’:

‘But in chess we get a fighting game which is purely intellectual and excludes chance.’

Page 104 of Modern Ideas in Chess (London, 1923):

The German original on page 56 of Réti’s book, Die neuen Ideen im Schachspiel (Vienna, 1922):

‘Da bietet sich uns im Schach ein Kampfspiel, das rein geistig ist und den Zufall ausschließt.’

When will it be realized that checking sources is indispensable?

10267. Dayton v Pearsall

A ‘Royal Walkabout’ game submitted by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA):

Eldorous Lyons Dayton – A.G. Pearsall

Correspondence

Danish Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Nxc3 Bc5 5 Bc4 d6 6 Qb3 Nc6 7 Bxf7+ Kf8 8 Bxg8 Rxg8 9 Nd5 Nd4 10 Qd3 Bd7 11 b4 Ba4 12 bxc5 Nc2+ 13 Kf1 Nxa1 14 Qf3+ Ke8 15 Qh5+ Kd7 16 Qf5+ Kc6 17 Nb4+ Kb5

18 c6+ Kxb4 19 Bd2+ Ka3 20 Qa5 b5 21 Qb4+ Kxa2 22 Bc1 Qf6 23 Ne2 Nb3 24 f4 Nxc1 25 Nxc1+ Ka1 26 Qa3+ Kb1 27 Qa2+ Kxc1

28 Ke2+ Resigns.

Source: Philadelphia Inquirer, 26 February 1950, page 22. Isaac Ash’s column stated that the game was ‘played in a recent mail contest’.

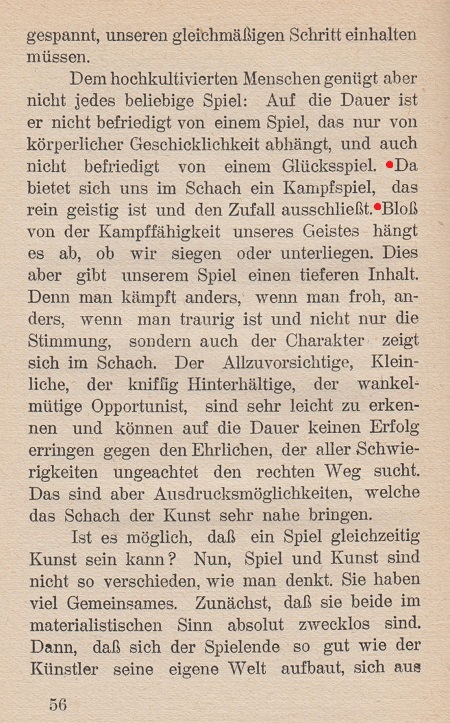

10268. Dayton on a Lasker simultaneous display

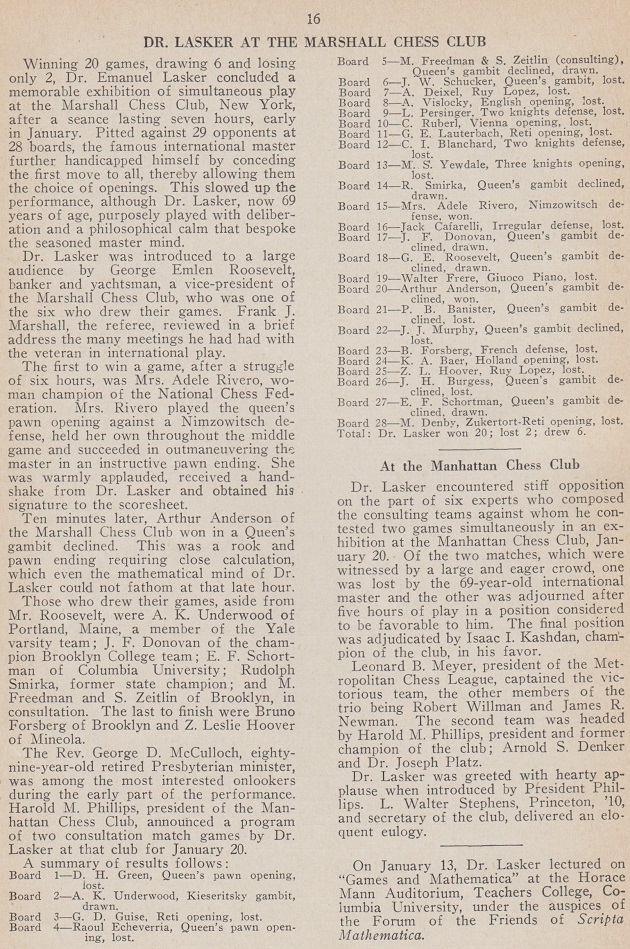

An example of Eldorous Dayton’s chess writing is taken from page 193 of CHESS, 14 February 1938:

Facts about the exhibition by Lasker (Marshall Chess Club, New York, 9 January 1938) were reported on page 16 of the January-February 1938 American Chess Bulletin:

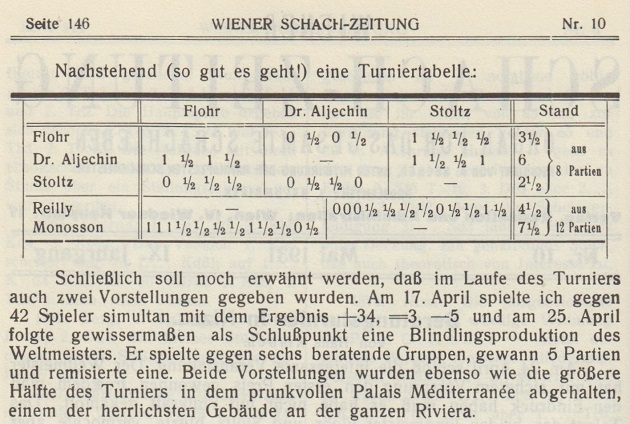

10269. Nice, 1931

Is it possible to find a better copy of the photograph,

with a full caption?

A tournament held in Nice earlier that year was won by Reilly, and a group photograph, which also included Duchamp, Mieses, Noteboom and Znosko-Borovsky, was published on page 201 of the May 1931 BCM. A clearer copy is on page 117 of the March 1981 issue.

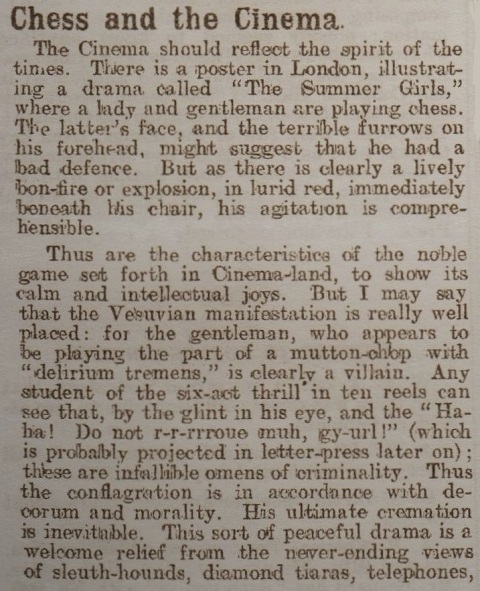

10270. The Summer Girls

From the ‘Problem Pages’ column by P.H. Williams on page 11 of the Chess Amateur, October 1919:

The poster for the film may be viewed online.

10271. Bird in Albany

From Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium):

‘At the end of May 1889 Bird made a short visit to the Albany Chess Club, and pages 563-564 of my recent book on him quoted some articles in the local press. The articles had a few illustrations of low quality which are of interest but were not included in the book.’

Albany Evening News, 24 May 1889, page 8

Albany Evening News, 25 May 1889, page 8

Albany Evening News, 25 May 1889, page 8.

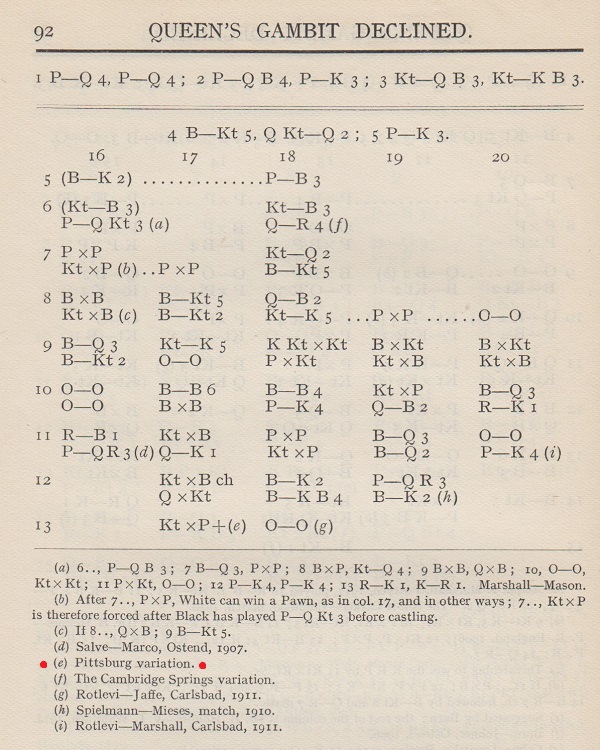

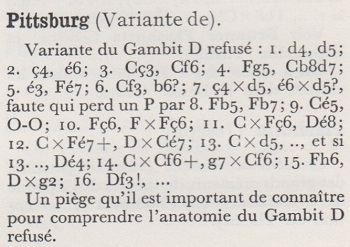

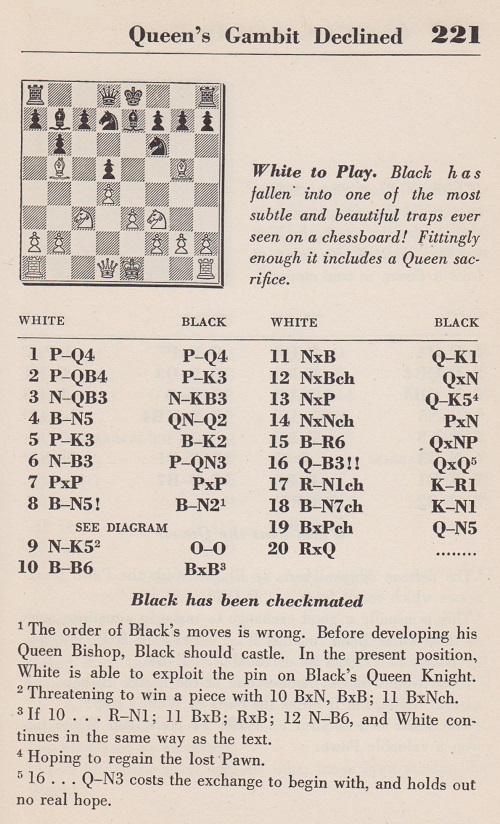

10272. The Pittsburg(h) Trap/Variation

White can play 17 Qf3.

We offer a solution to the long-standing mystery of how the ‘Pittsburg(h) Trap/Variation’ obtained its name(s).

Modern Chess Openings by R.C. Griffith and J.H. White (London, 1913), page 92. (See too many other editions.)

Dictionnaire des échecs by F. Le Lionnais and E. Maget (Paris, 1967), page 301

The matter was often referred to by Irving Chernev, e.g. on the inside front cover of the October 1951 issue of Chess Review:

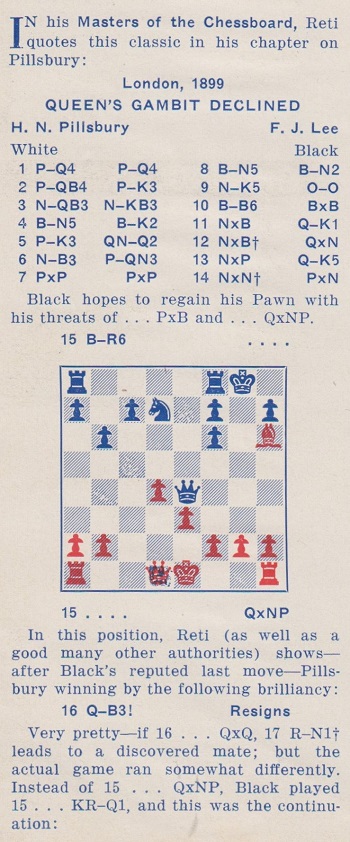

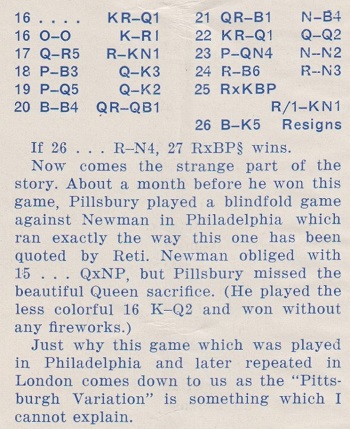

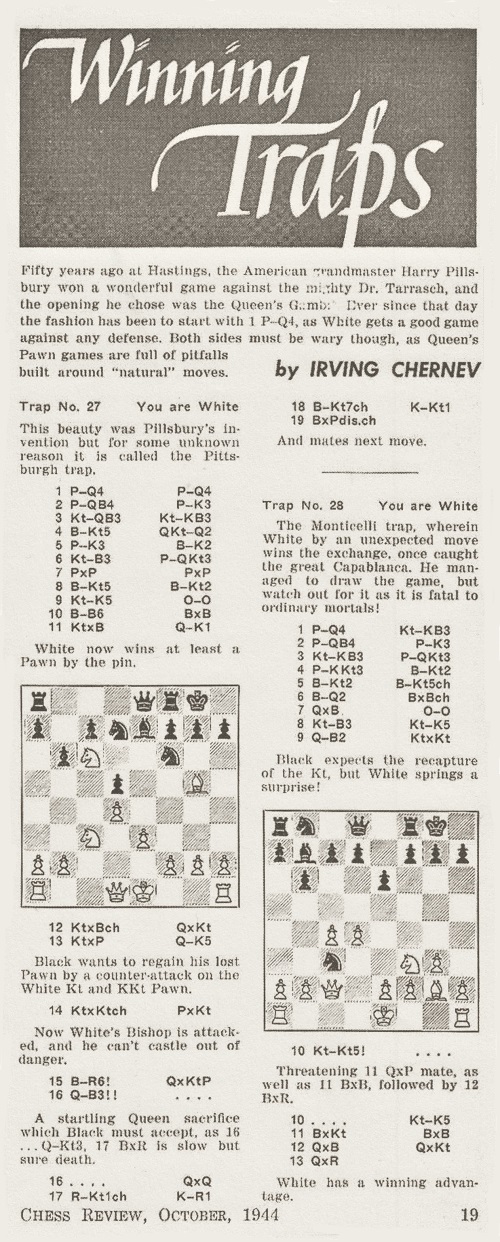

Chernev had written similarly in his ‘Winning Traps’ column on page 19 of the October 1944 Chess Review:

See too pages 52-53 of Chess in an Hour by F.J. Marshall and I. Chernev (New York, 1968), where Chernev wrote in his additions:

‘This beautiful trap was originated by Pillsbury, who used it with great effect against Lee in their tournament game at London in 1899, but for some strange reason it is known as the Pittsburgh trap.’

In a note to Capablanca v Teichmann, Berlin, 1913 on page 57 of Capablanca’s Best Chess Endings (Oxford, 1978) Chernev wrote: ‘the Pittsburgh Trap is subtle, effective and painless – the victim scarcely realizing he is in it until it is too late.’ Without mentioning any names, Chernev gave a similar line on page 221 of Winning Chess Traps (New York, 1946): ‘Black has fallen into one of the most subtle and beautiful traps ever seen on a chessboard’.

Pre-Chernev books which noted the line, without any reference to Pillsbury or Pittsburg(h), included the works on traps by E.A. Greig and E.A. Znosko-Borovsky.

For further background information on Pillsbury’s games

against Lee and Newman, as well as references to

‘Pillsbury’s Mate’, see C.N. 5772. It will be noted that

in the 1951 Chess Review article shown above

Chernev was wrong to state that Pillsbury v Newman was

played ‘about a month before’ Pillsbury v Lee. It was

played the following year. The London, 1899 tournament

book (pages 157-158) missed the possibility of 16 Qf3 in

Pillsbury v Lee.

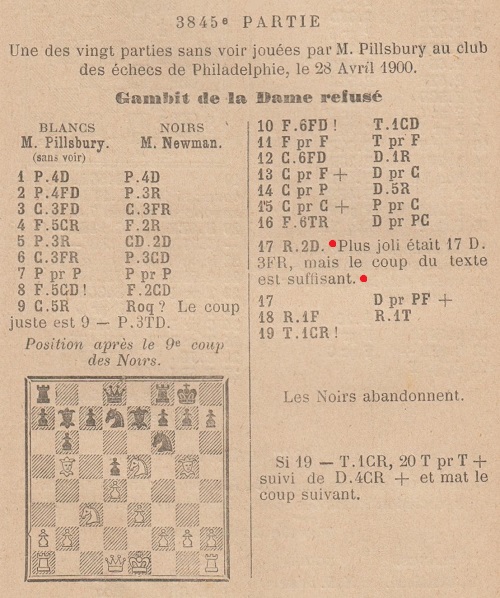

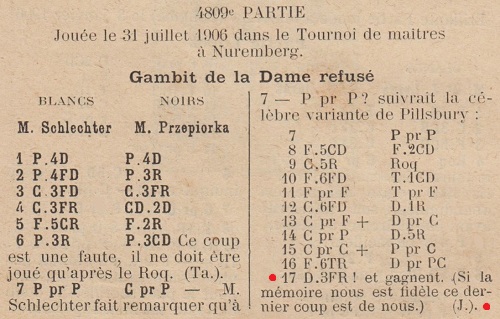

The game against Newman was published on page 299 of La Stratégie, 15 October 1900, with 17 Qf3 mentioned in a note:

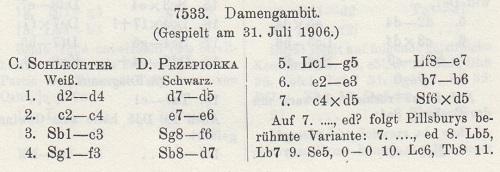

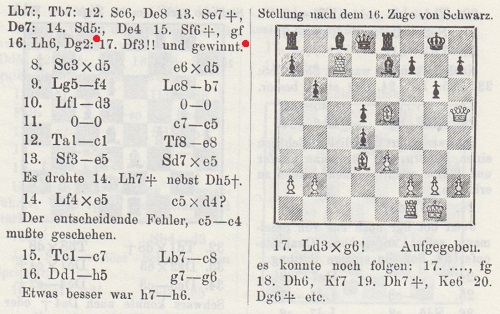

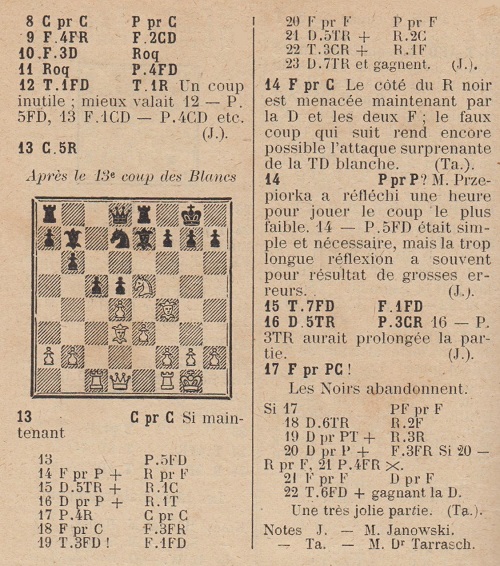

Six years later the move 17 Qf3 was given in annotations to the game Schlechter v Przepiórka, Nuremberg, 1906, on pages 235-236 of the August 1906 Deutsche Schachzeitung (of which Schlechter was the co-editor):

Annotating the game on pages 333-334 of La Stratégie, 19 November 1906, Janowsky referred to Schlechter’s annotations and stated, regarding 17 Qf3:

‘Si la mémoire nous est fidèle ce dernier coup est de nous.’

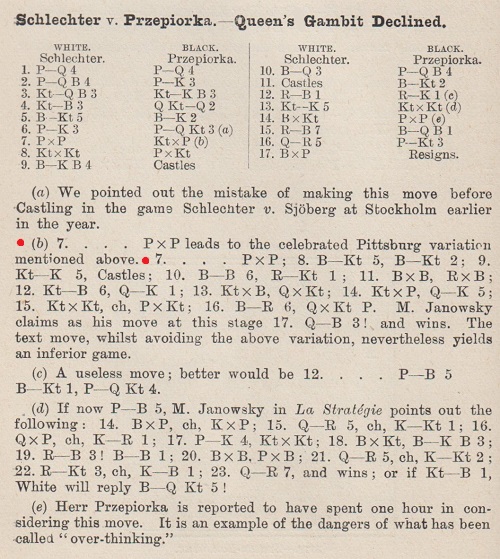

When the Schlechter v Przepiórka game was published on page 188 of The Year-Book of Chess, 1907 by E.A. Michell (London, 1907) use was made of Janowsky’s annotations:

Thus the term written by Schlechter (‘Pillsburys berühmte Variante’) which was quoted by Janowsky (‘la célèbre variante de Pillsbury’) became, in the Year-Book, ‘the celebrated Pittsburg variation’.

Janowsky’s notes had also been mentioned on page 185 of the Year-Book (in connection with Marshall v Spielmann, Nuremberg, 1906); the Schlechter v Sjöberg game was on pages 47-48.

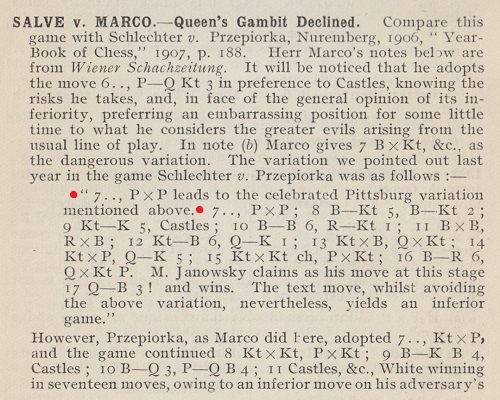

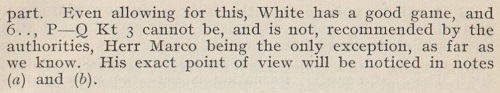

The Pillsbury/Pittsburg mix-up was repeated when Salwe v Marco, Ostend, 1907 was published on pages 174-177 of Michell’s The Year-Book of Chess, 1908 (London, 1908). The introductory note:

A third occurrence of ‘Pittsburg Variation’ (this time, ‘the entire Janowsky variation of the Pittsburg Variation’) came in a report on Scarborough, 1909 on page 142 of The Year-Book of Chess, 1910 (London, 1910), also edited by E.A. Michell:

Following the confusion between Pillsbury and Pittsburg, confusion between Pittsburg and Pittsburgh was inevitable, and both spellings became common. For example, the 1918 BCM volume had ‘Pittsburg variation’ (January, page 21) and ‘Pittsburgh variation’ (August, page 240). Use of a place name was not queried, and ‘The Pittsburg variation’ even appeared (referring to 8 Bb5) when Pillsbury v Newman was published on page 204 of Pillsbury’s Chess Career by P.W. Sergeant and W.H. Watts (London, 1923).

10273. Owen Dixson

C.N. 6360 showed two images from My Way with Polio by Owen Dixson (London, 1963). Below, from opposite page 30, is the third one:

From one of our inscribed copies of the book:

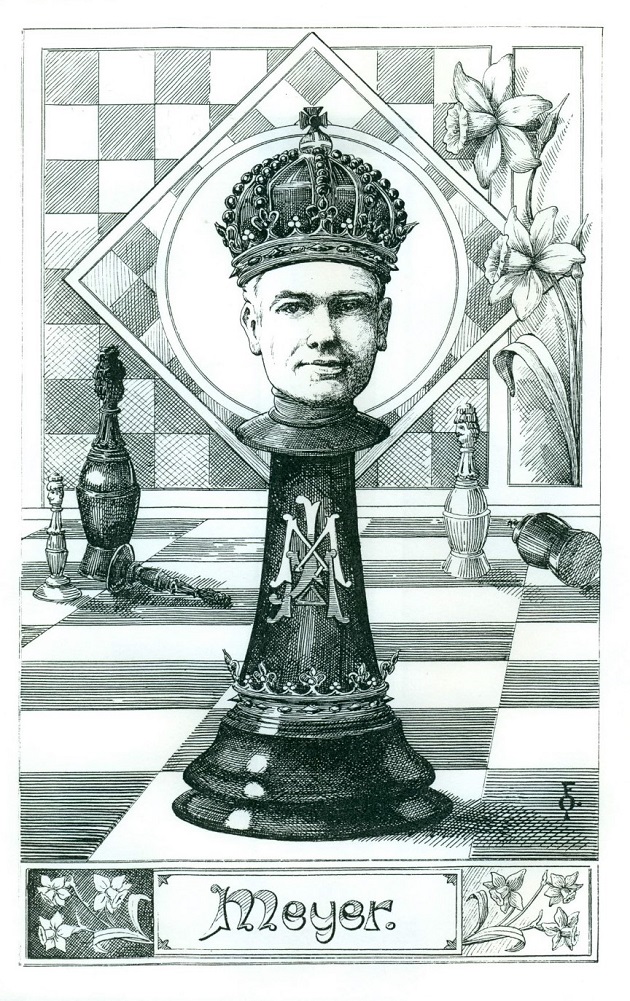

10274. Frederick Orrett

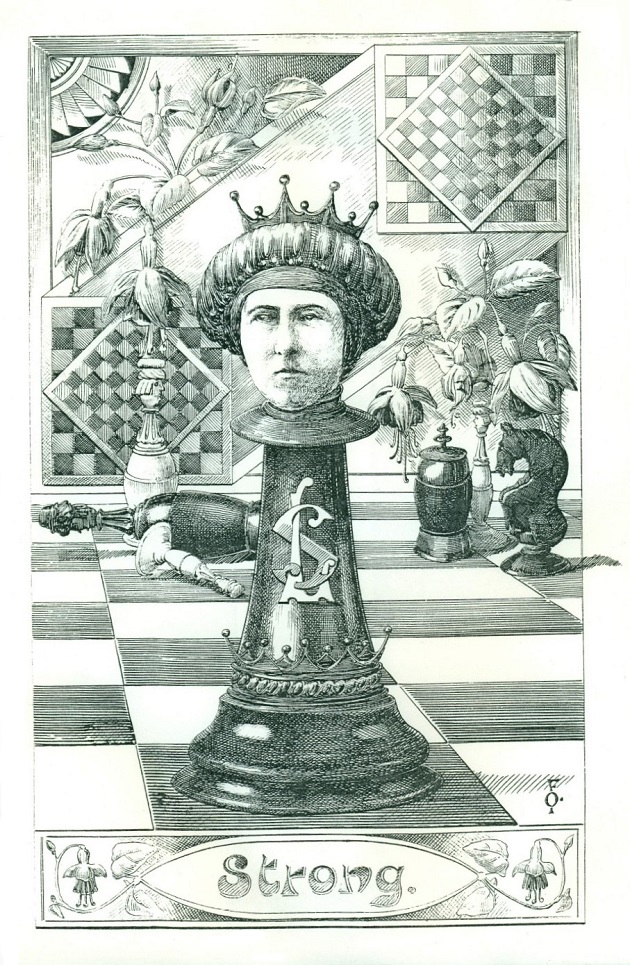

Max Julius Meyer

Lilian Edith Strong (née Baird)

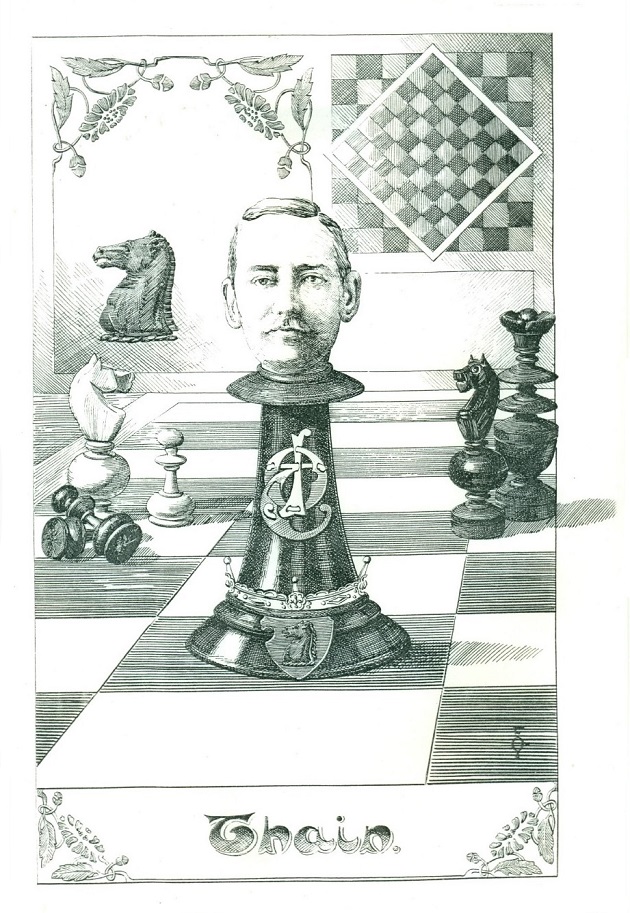

J.O. Thain

That concludes the extensive set of portraits by Frederick Orrett kindly supplied by Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England).

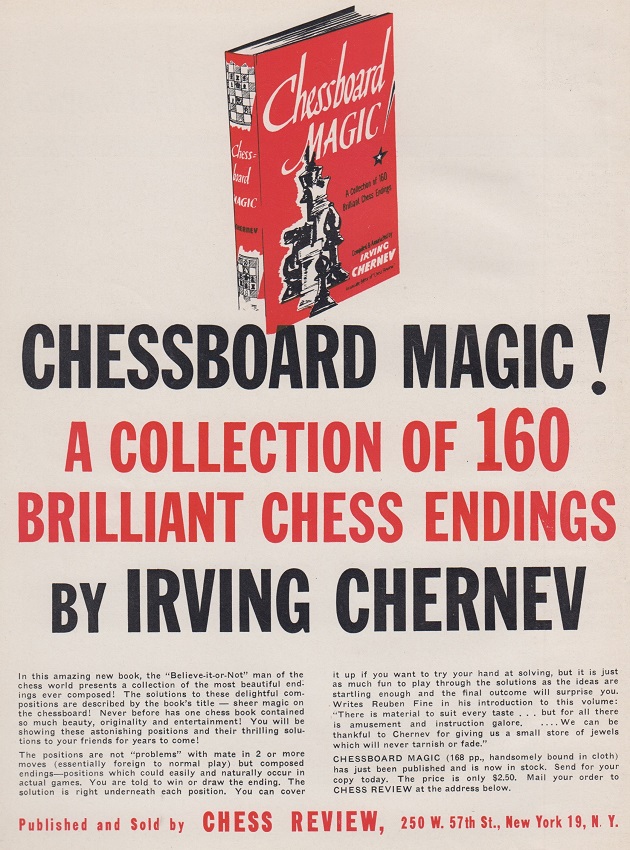

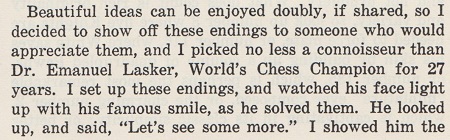

10275. Chessboard Magic!

White to move

Page 173 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

Chernev was certainly a leading popularizer of endgame compositions, and particularly with his 1943 book Chessboard Magic!

Chess Review, January 1944, inside front cover

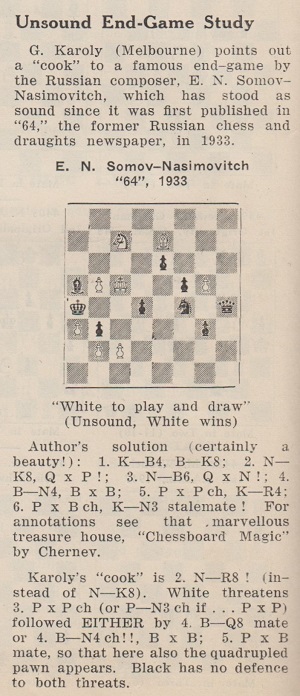

In the Preface (pages ix-x) Chernev related Emanuel Lasker’s enthusiasm for studies:

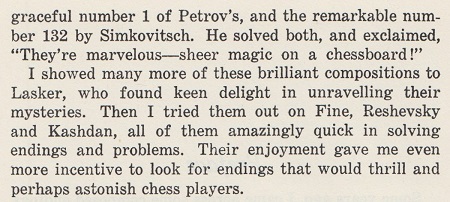

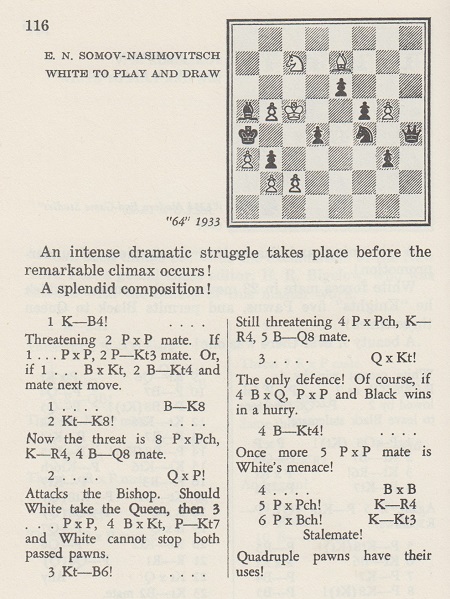

A few of the compositions in Chessboard Magic! were faulty, such as this one:

In the ‘Ask the Masters’ feature on page 284 of the May 1979 Chess Life & Review a reader, James Joyce of Missouri, wrote:

‘Didn’t the composer (Somore – Nasimotich [sic]) and the annotator (Irving Chernev) both miss a mate in five? 1 K-B4 B-K8 2 PxPch K-R4 3 N-R8 Q-R1 (or 3...N-Q4 4 B-Q8ch N-N3ch 5 BxN mate) 4 B-N4ch BxB 5 PxB mate.’

Pal Benko responded:

‘You are right that the mate is much stronger than the intended 1 K-B4 B-K8 2 N-K8 QxP 3 N-B6 QxN 4 B-N4 BxB 5 PxPch K-R4 6 PxBch K-N6 [sic] stalemate. I don’t feel sorry for this endgame. The setup is very superficial and there is too much material, so the “magic” part of it is unclear. But feel sorry for the composer, for it is impossible to make every endgame cookproof; so far the computer can verify only direct mates.’

We add that the unsoundness of this study by Evgeny Nikolaevich Somov-Nasimovich (1910-42) had already been demonstrated (with Na8 on move two) by G. Karoly of Melbourne on page 70 of Chess World, 1 March 1950:

| First column | << previous | Archives [149] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.