Chess Notes

Edward

Winter

When contacting

us

by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include

their name and full

postal address and, when providing

information, to quote exact book and magazine

sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the

subject-line or in the message itself.

6100. Chess flower

Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) sends this photograph,

taken in his garden, of the ‘chess flower’ (Fritillaria

meleagris):

Stewart Shirley Blackburne

(1857-1934) was the author of Terms and Themes of

Chess Problems (London, 1907). His obituary on

page 409 of the October 1934 BCM referred to

other sporting interests (‘he also wrote rules for the

Lawn Tennis Association, 1883; for the New Zealand

Chess Association, 1906; and for the Canterbury

Croquet Association’), and Michael McDowell

(Westcliff-on-sea, England) draws our attention to a New

Zealand webpage which states that Blackburne

‘occasionally represented Doncaster in cricket and

football, and frequently in lawn tennis matches’.

As mentioned on pages 232-233 of Chess

Explorations and page 101 of Chess Facts and

Fables, the late Alistair Cooke drew parallels

between chess and American football. For an old

discussion of the same topic, see ‘Strategy in the New

Football’ by Walter Camp on pages 87-90 of Lasker’s

Chess Magazine, December 1907.

This photograph has been submitted by Lawrence Totaro

(Las Vegas, NV, USA). Who was Tal’s opponent and what

was the event?

From page 22 of Relax with Chess by Fred

Reinfeld (New York, 1948):

‘It was that exuberant phrase-maker and

paradox-monger Dr Tartakower who once remarked that

a pawn sacrifice requires more skill than does a

queen sacrifice. The reason? Sacrificing the queen

calls for exact calculation of a quick finish. The

pawn sacrifice, on the other hand, involves an

intuitive flair possessed as a rule only by the

great masters.’

Where did Tartakower make such a remark?

Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA) writes:

‘A photograph showing Basil Rathbone, David

Burton and Nick Grinde gathered around the same

board as in C.N. 6099 appears on page 261 of the

May 1979 issue of Chess Life & Review

with the following caption:

“Basil Rathbone, before his series of film

portrayals of Sherlock Holmes, with crew members

discussing a scene in The Bishop Murder Case,

in which he played supersleuth Philo Vance.”

It comes in an article entitled “Chess in the

Cinema: Films of the Thirties”, one of a series of

articles by Frank Brady which appeared in the

magazine in 1979, and it discusses the film in

some detail.’

6106.

Bird

comment

From page 23 of My one Contribution to Chess by

F.V. Morley (New York, 1945):

‘Bird had written books. When he was in a difficulty

he used to say: “It’s all in my book – I’m sure the

answer to that is in my book.”’

Wanted: nineteenth-century corroboration of the Bird

remark (which appeared on page 29 of the London, 1947

edition of Morley’s work).

Pablo S. Domínguez (Madrid) notes that a different

account of the Simagin-Šajtar episode was given, sin

fuente, on pages 115-116 of the light-hearted

book La guía del perfecto tramposo … en Ajedrez by

Antonio Gude (Madrid, 1992).

From page 239 of Point Count Chess by I.A.

Horowitz and Geoffrey Mott-Smith (New York, 1960):

‘The ultimate triumph of the open file is to get a

rook to the seventh rank, whence it strikes at the

enemy pawn base. This “pig” (Spielmann’s epithet) is

the more odious when it also menaces the king.’

Can any details be found in Spielmann’s writings?

Tal’s opponent was Eugenio Szabados. In late October

and early November 1957 the future world champion made

a tour of Italy, and in a team match between Riga and

Venice on 31 October and 1 November he defeated

Szabados twice. See page 366 of Storia degli

scacchi in Italia by Adriano Chicco and Antonio

Rosino (Venice, 1990) and pages 164-168 of the first

‘Chess Stars’ volume of Tal’s games (1949-1962) edited

by Alexander Khalifman. The latter book gave only the

game in which Szabados was White.

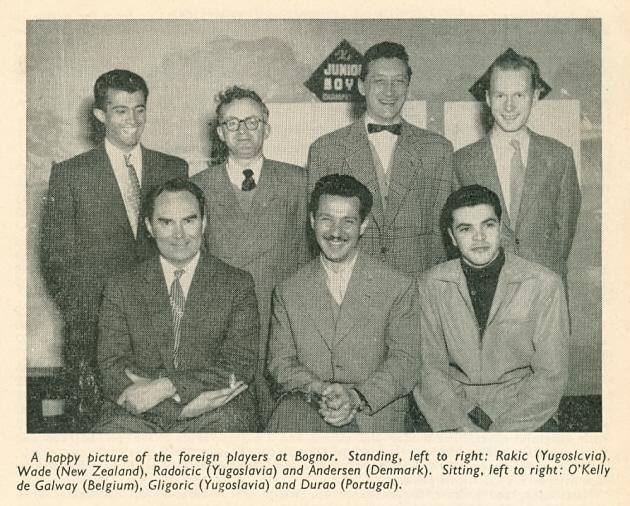

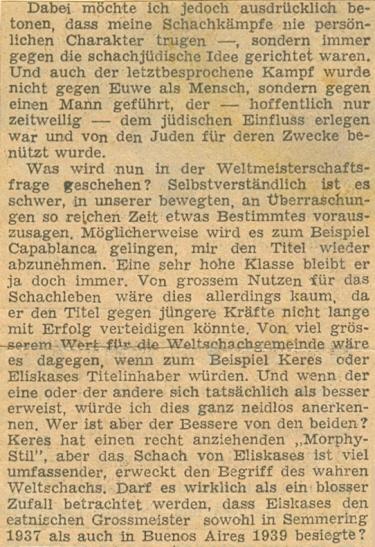

Below is a photograph from opposite page 56 of the

Venice, 1949 tournament book:

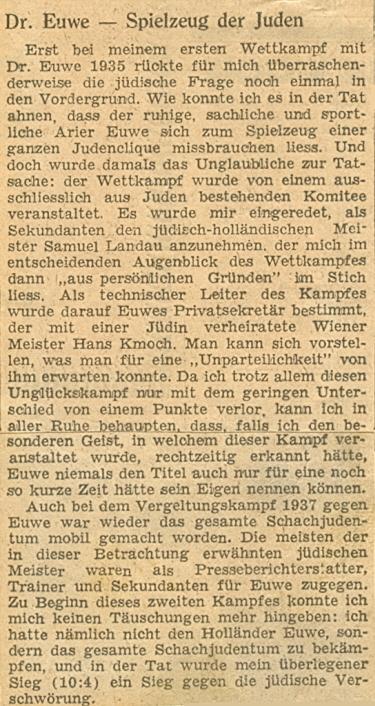

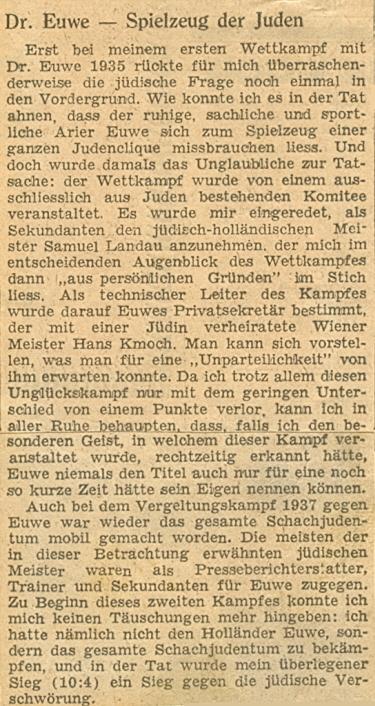

6110. Anti-Semitic articles

Regarding the anti-Semitic

articles published in 1941 under Alekhine’s name,

Henk Smout (Leiden, the Netherlands) writes:

‘The June-July 1942 issue of the Tijdschrift

van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond reported on a

congress in Salzburg (held during a tournament won

by Alekhine) concerning the foundation of an

“Europaschachbund” (European Chess Federation). At

the congress Alekhine was the French representative,

and the magazine’s report (page 88) contained the

following “rectification”:

“Gedurende dit congres heeft dr Aljechin tegenover

den secretaris van den Ned. Schaakbond zijn

leedwezen betuigd over het misverstand, dat zich in

het afgeloopen jaar heeft voorgedaan als gevolg van

een onjuiste publicatie betreffende het dr

Euwe-comité, in het bijzonder ten opzichte van dr

Euwe en de heeren Van Harten en Liket.”

[“During this congress Dr Alekhine expressed

regret to the secretary of the Dutch Chess

Organization about the misunderstanding which

occurred last year in consequence of an incorrect

publication concerning the Euwe committee, and in

particular with respect to Dr Euwe and Messrs Van

Harten and Liket.”]

This was understandable only to those who knew the

Pariser Zeitung of 23 March 1941 or the Deutsche

Zeitung in den Niederlanden of 2 April 1941. It

related to the final anti-Semitic article, which

stated that the organizing committee of the 1935

match with Euwe had consisted exclusively of Jews

and that Euwe was a plaything of the Jews.

That article was not included in the Deutsche

Schachzeitung’s serialization. The German

magazine’s last instalment concluded on pages 82-84

of the June 1941 issue, and the promise “Fortsetzung

folgt” was left unfulfilled, without explanation. It

may, though, be relevant that Euwe had long been

listed by the Deutsche Schachzeitung as a

contributor. (He also became a “Mitarbeiter” of the

Deutsche Schachblätter, the official organ of

the Grossdeutscher Schachbund, as from the April

1941 issue.)

Approximately 40% of the text of the anti-Semitic

articles was not republished in the Deutsche

Schachzeitung and was therefore also absent from CHESS,

which printed an English translation of what had

appeared in the Deutsche Schachzeitung.’

Below we reproduce from our collection the relevant

part of the article as it appeared in the Deutsche

Zeitung in den Niederlanden:

The letter below, written by J.H. Sarratt in 1810,

was reproduced in C.N. 1047 courtesy of Michael

Macdonald-Ross, its owner at that time (1985):

‘Pulteney Malcolm, Esq., &c. &c.

Sir,

The reasons which induce me to trouble you with

this communication, will, I trust, appear to you a

sufficient apology for it.

On Saturday morning, when Mr G. Sarratt arrived in

Town, I was just beginning to recover from an

illness, which, though of no considerable duration,

has been very severe. The precarious state of my

health induced me to express a desire, that Mr

Sarratt should remain with me a few days,

particularly as I was very anxious to explain fully

to him the mystery which has enveloped his early

years.

He felt exceedingly uneasy from the fear, that, if

he complied with my earnest wish, he might perhaps

subject himself to a charge of apparent remissness

in the discharge of his duty, and thus expose

himself to be deprived of that meed, which, I know,

he most highly prizes – your approbation.

However, he promised to remain with me three or

four days, on the condition that I should engage to

acquaint you with the motives of his stay – Of

course I most willingly acquiesced in a wish

dictated by propriety; and upon further

consideration, I judged it to be my duty to

communicate the following particulars to you Sir,

under whose mild and judicious sway, Mr S. will I

fervently hope, continue to improve in his “gallant

profession”, and render himself deserving of that,

after which he so ardently sighs, promotion. –

I was scarcely eighteen when I married Mr S.’s

mother in the year 1790: he was at that period three

years of age, being born June 21st 1787. At the age

of sixteen his mother had been seduced by Major John

Kelly: about a year after that unhappy event Mr S.

was born – But few months had elapsed since his

birth, when Major Kelly, regardless of his vows and

his re-iterated promises of making her his wife,

quitted the Island of Jersey, and left his destitute

victim to tears and misery. Her father for a long

time was implacable in his resentment, but relenting

at length in consequence of the intreaties of an old

and excellent female relative, he consented to be

reconciled to his daughter, though he withheld all

the tokens of affection from the hapless pledge of

her ill-fated affection.

Some months after my marriage, I suggested to my

wife the propriety of her son’s calling me father,

and being taught to consider me as his parent: of

course she assented to it, and that is the origin of

his being called Sarratt, although his name

is Kelly.

George Strange Nares, Esq. Captain, Light Company

70th. Foot, was his Godfather. He is since dead, and

neither Major Kelly nor he ever evinced the least

solicitude for the welfare of my adopted son.

Some weeks after Mrs Sarratt’s death, which

happened six years ago I wrote to George and in a

few words informed him, that, he was not my

son; at the same time I told him, that, if he wished

it, he

was perfectly at liberty still to sign his name “G.

Sarratt”, and I repeated to him, that, as long as he

continued to behave properly, he might consider me

as his unalterable and dearest friend. His affection

for me impelled him to declare, that, he should

never use any other name, that, he had never known

his father, and, that, he should ever consider me

as his parent.

It may perhaps not be superfluous to add, that, he

was born in the Island of Jersey, and, that, his

mother was daughter of an eminent Surgeon.

With respect to his Extract of Baptism

which I understand will be of utility to him, I beg

to observe, that, from the foregoing statement, it

may not be easy to obtain it: However, if it be

requisite that he should have it, I should endeavour

to procure it.

I have again to apologise for this intrusion, and,

with the highest respect,

I have the honour to remain,

Sir,

Your most obedient servant,

J.H. Sarratt.

Emigrant Office,

Bloomsbury.

12th. November 1810’

The letter from Sarratt to Malcolm was enclosed in

another letter from Malcolm to Mrs Malcolm:

(Postmarked 21 November 1810)

‘The enclosed (has) the history of your protégé

Sarratt alias Kelly – is Mrs Robinson sister to his

mother – I will be of advantage to him hereafter –

that he is a natural born subject of His Majesty –

As I know you would enjoy beating me at Chess – I

would commend you to (serve assistance to) old

Sarratt – who is a professor of Chess – writes Books

and gives lectures on it – we have one of them on

board.

PM

You must pay postage.’

(Addressed to:) Mrs Malcolm, East Lodge, Enfield,

Middlesex.

C.N. 1047 added that an entry on P. Malcolm

(1768-1838) is to be found in the Dictionary of

National Biography and that, in his letter

above, parentheses indicate parts which are not clear.

6112. Fine v Alexander

Björn Frithiof (Almhult, Sweden) asks about the game R.

Fine v C.H.O’D. Alexander, Margate, 1937, which appears

as follows in his database (ChessBase) and on pages

154-155 of Reuben Fine by A. Woodger (Jefferson,

2004): 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Qc2 Nc6 5 Nf3 d6 6

a3 Bxc3+ 7 Qxc3 O-O 8 b4 e5 9 dxe5 Ne4 10 Qe3 f5 11 Bb2

Nxe5 12 Nxe5 dxe5 13 g3 Be6 14 f3 Nd6 15 Qxe5 Qe7 16 e3

Qf7 17 c5 Nc4 18 Bxc4 Bxc4 19 Kf2 Bb3 20 Bd4 Rae8 21 Qf4

Bd5 22 Be5 Bxf3 23 Bxg7 Bxh1 24 Bxf8 Rxf8 25 Rxh1 Qa2+

26 Kf1 Qxa3 27 Kg2 Qb2+ 28 Kh3 Qe2 29 Rf1 Qg4+ 30 Kg2

Re8

31 Qxf5 Qxb4

32 Rf4 Qd2+ 33 Kh3 Qxe3 34 Qd7 Qe7 Drawn.

Our correspondent comments:

‘What puzzles me is the conclusion of the game,

after 31...Qxb4. White is said to have played 32 Rf4

(instead 32 Qf7+, which wins at once), and after the

further moves 32...Qd2+ 33 Kh3 Qxe3, White had an

immediate win with 34 Rg4+.’

We believe that White’s 31st move was mistranscribed as

Qxf5 instead of Qxc7, i.e. QxKBP rather than QxQBP. The

move was given as 31 QxQBP on page 304 of the June 1937

BCM and on pages 51-52 of The best games of

C.H.O’D. Alexander by Harry Golombek and Bill

Hartston (Oxford, 1976).

6113. Gluing and nailing

Page 156 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves

commented:

‘Numerous books assert that Carl Carls always played

1 c4, except on the occasion when his c-pawn was glued

to the board. In fact, games in which Carls opened as

White with another first move may even be found in the

monograph Carl Carls und die “Bremer Partie”.’

A less common tale, on which we have no further

information, appeared on page 4 of Relax with Chess

by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1948):

‘The story goes that a practical joker, taking

advantage of Akiba Rubinstein’s predilection for 1

P-Q4, once nailed down the grandmaster’s queen’s

pawn.’

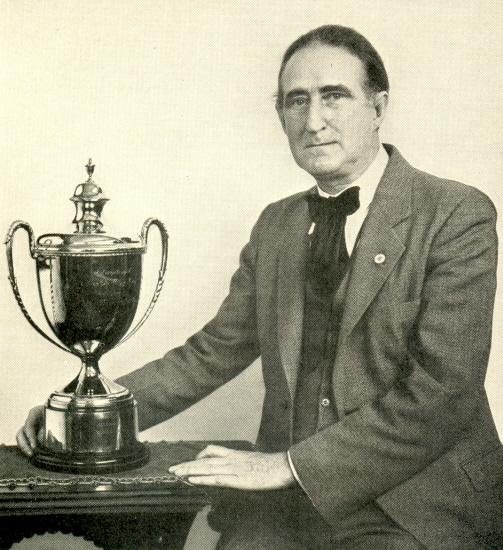

This is Frederick Gustavus Hamilton-Russell

(1867-1941), in a photograph which appeared in the

June 1926 BCM. A portrait of Frank Marshall

with the Hamilton-Russell Cup was the frontispiece of

Marshall’s Comparative Chess (Philadelphia,

1932):

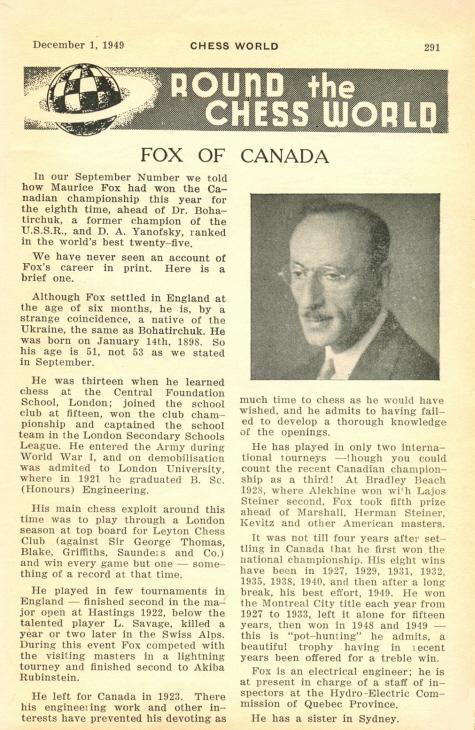

John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) writes:

‘Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia states

that the Canadian master Maurice Fox was born on

14 January 1898 in the Ukraine, as per the account

in Chess World, December 1949, page 291.

That magazine also says that Fox settled in

England at the age of six months. Did his parents

emigrate to England or were they British nationals

returning after residing in the Ukraine? This

leads to the question of whether or not he was

born “Maurice Fox”. Also, was his birth-date 14

January 1898 in the Gregorian or the Julian

calendar?’

Below is the biographical item in Chess World referred

to by Mr Donaldson:

From page v of Chess Brilliants by I.O.

Howard Taylor (London, 1869):

‘Position is everything. To give up a pawn is

sometimes a bolder venture than to abandon a queen.’

6117. Ill (C.N.s 5890 & 6058)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) quotes from page 7

of part two of the New

York Daily Tribune, 3 January 1897 (a letter

dated 17 December 1896 just received from Steinitz in

Moscow):

‘Why am I so badly beaten? In the first place,

because Lasker is the greatest player I ever met,

perhaps the greatest that ever lived; to say so

positively would be like making excuses for myself and

disparaging other rivals at a time when I myself am

incapable to compete in the first rank. “A chess

master has no more right to be ill than a general on

the battle-field”, or words to that effect, I once

wrote in the International Chess Magazine, and

I adhere to that.’

We cannot explain why this wording is different from

what appears on page 337 of William Steinitz, Chess

Champion by Kurt Landsberger, where Steinitz’s

letter was quoted as stating, for example, ‘A chess

master has the same right to be sick as a general on the

battlefield’. It may be recalled from C.N. 6058 that Mr

Landsberger said that he was citing Steinitz’s letter as

published in the New York Sun, also of 3 January

1897.

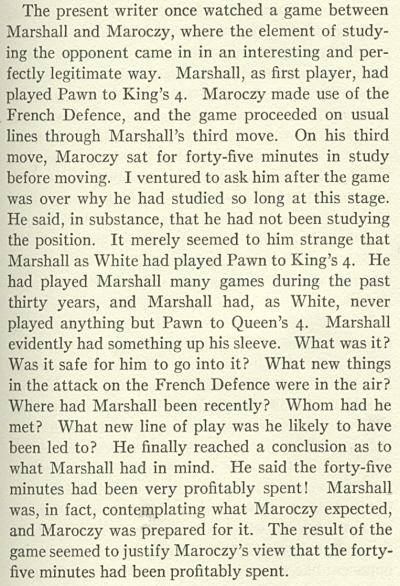

Below is an extract from pages xix-xx of the Preface

by Benjamin M. Anderson Jr to Capablanca’s A

Primer of Chess (New York, 1935):

The passage was discussed in C.N.s 706 and 1177 (see

pages 117-118 and 263 of Chess Explorations),

and for the game in question we can still offer only

one candidate: Marshall v Maróczy, Lake Hopatcong,

1926. As mentioned in C.N. 5991, Anderson was in Lake

Hopatcong at the time.

6119. Buenos Aires, 1939

This photograph of the team from Bohemia and Moravia at

the 1939 Olympiad is reproduced from Nad

šachovnicemi celého světa by K. Opočenský and V.

Houška (Prague, 1960):

Our earlier items (see page 268 of Kings,

Commoners and Knaves, page 289 of A Chess

Omnibus and C.N. 4823) recorded such mishaps as

David Spanier’s description of Nimzowitsch as ‘one of

the great masters of nineteenth-century chess’. Now we

add another specimen:

‘Caissa is the Muse of Chess and was the creation

of Sir William Jones, a famous seventeenth-century

orientalist.’

Source: page 189 of The Chess Scene by D.

Levy and S. Reuben (London, 1974).

6121. The Pride and Horror of British

Chess

William Winter

The article below by G.H. Diggle, the ‘Badmaster’,

comes from page 74 of our publication Chess

Characters (Geneva, 1984). It first appeared in Newsflash,

October 1981.

‘William Winter (1898-1955), twice British Champion,

a fine chess teacher, and a writer “who could put into

one sentence as much as others could into a

paragraph”, might have been called in his heyday “The

Pride and Horror of British Chess”. Sometimes (notably

Yarmouth, 1935 and Scarborough, 1928 where he was

accompanied by a lady friend who kept an eye on him

like a Probation Officer) he would appear in a college

blazer and well-pressed flannels looking like an

ascetic curate on holiday – on other occasions he

would have been blackballed on sartorial grounds had

he attempted to join a village club consisting

exclusively of scarecrows. At London, 1945, though

reporting only and not competing, he represented the

quality press in denims and a tattered old sweater

full of holes. It is curious that such a highly

educated and cultured man, a courteous and

conscientious chess professional in every other

respect, never seemed to realize that even

chessplayers (the cream of human abnormality) set some

limit to hygienic eccentricity. It certainly lost him

professional business. The BM was once on the

Committee of a local club and the question of whom to

invite to give a simul cropped up. The BM, always a

“buy British” patriot, suggested Winter and extolled

his chess genius, but was routed by a masterful lady

member who said “that was all very well, but she

refused to be checkmated by the hand of genius if it

was garnished with dirty nails”. But strangely enough,

Winter himself was physically fastidious in some ways.

At Scarborough, as he once remarked afterwards, he

actually agreed to a premature draw with the tailender

Dr Schubert solely because he could not put up with

the Doctor’s chewing gum.

His fairness and sportsmanship over the board were

generally agreed to be of the highest order. The BM

once heard him relate the following (he was a vigorous

and animated raconteur with a staccato voice which

tended to rise to a crescendo as he “neared the

goal”): “I was playing in a County Match and after a

hard struggle was about to play the winning move when

some old duffer (he always referred to chess

rabbits as Duffers with a great accent on the “D”) –

“some old duffer with a whisper like a foghorn

hissed out N-B7 and unfortunately it was the right

move. As I could find no other way to win, of

course the game had to end in a draw.”

Even when at his least presentable, Winter always had

a vivid personality. Had he cultivated a presence as

well, and had his beard trimmed, he might have ranked

with Tarrasch as a great chess pedagogue. But he would

have got on better with Labourdonnais, like whom

Winter retained his chess faculties to the last. It

was even said that he solved a problem on the very day

of his death.’

The remark about his writing and annotations (‘he was

lucid, putting into a sentence as much as many others

put into a paragraph’) appeared in his obituary by

‘J.G.’ (James Gilchrist) on pages 28-29 of the January

1956 BCM.

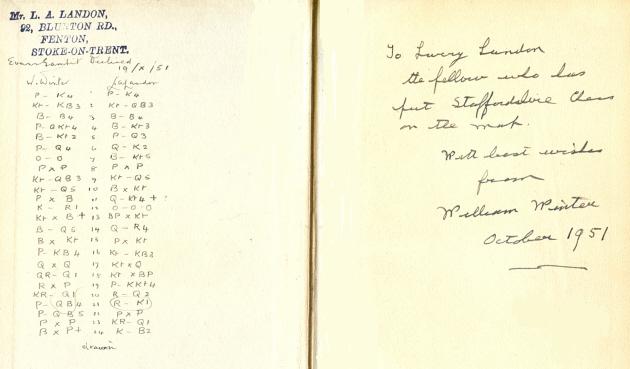

This inscription and game come from one of our copies

of William Winter’s Chess for Match Players

(London, 1951):

6122. Rabbit quote

Page xii of The

Treasury of Chess Lore by F. Reinfeld (New York,

1951)

Page 15 of Chess

Quotations from the Masters by H. Hunvald (Mount

Vernon, 1972)

Above are just two examples of how ‘chess literature’

presents quotes. Not only is the source limited to a

single word, ‘Mortimer’, but the texts differ. For

instance, there is a choice between ‘cogitative’ and

‘cognitative’, and in this famous quote some websites

offer a third option: ‘cognitive’.

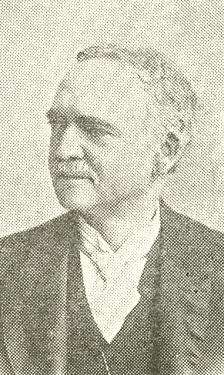

We have therefore gone back to the original text, in an

article by James Mortimer entitled ‘How to Win at Chess’

on page 9 of the Daily Mail, 6 October 1906:

‘To those who have taken up chess as an intellectual

and fascinating pastime, and who are often beaten at

odds by players of inferior grammar, it will be

cheering to know that many persons are skilful chess

players, though in some instances their brains, in a

general way, compare unfavourably with the cogitative

faculties of a rabbit. They are simply familiar with

the openings – the well-beaten paths discovered or

devised by the masters of the game.’

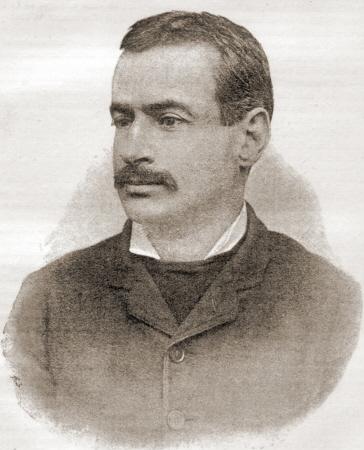

The above photograph of Mortimer was published on page

115 of The Rice Gambit by H. Keidanz (New York,

1905). For portraits of higher quality, see C.N.s 4845

and 4879.

Following publication of the agreement signed by

Lasker and Marshall on 26 October 1906 for a world

championship match (see pages 147-148 of Lasker’s

Chess Magazine, August-September 1906) James

Mortimer quoted a few unhappy passages on page 8 of

the Daily Mail, 5 December 1906 and commented:

‘All this is wonderfully weird. It may be very good

Liskeranto or very elegant Marshallpuk, but it is

certainly not very good English.’

6124.

Amy

Lowell

Bradley J. Willis (Sherwood Park, Alberta, Canada)

quotes a composition from page 136 of Amy Lowell:

Selected Poems edited by Honor Moore (New

York, 2004):

Still Life

Moonlight Striking upon a Chess-Board

I am so aching to write

That I could make a song out of a chess-board

And rhyme the intrigues of knights and bishops

And the hollow fate of a checkmated king.

I might have been a queen, but I lack the proper

century;

I might have been a poet, but where is the adventure to

Explode me into flame.

Cousin Moon, our kinship is curiously demonstrated,

For I, too, am a bright, cold corpse

Perpetually circling above a living world.

Our correspondent notes that in 1926, the year after

her death, Amy Lowell was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for

Poetry.

She was a cousin of Robert Lowell, two of whose works

were given on pages 67-68 of The Poetry of Chess

edited by Andrew Waterman (London, 1981).

From the chess column of Robert John Buckley in

the Birmingham Weekly Mercury of 15 April 1905,

page 25:

‘A curious and apparently contradictory feature in

James Mason’s character was his interminable patience.

Racially, Mason was of the most impatient, the most

impulsive, the most hot-headed temperament in Western

Europe. Mason was a Kelt of the Kelts, a really Irish

Irishman, and not in the smallest fragment of his

being, one of the Scots-Irish or the Anglo-Irish who

dominate Ulster.

And here I may tell the world something which has not

before been hinted, either in print or, so far as I

know, in any other way.

James Mason’s true name was neither James nor Mason.

His real name was confided to me years ago, as it

were, sub sigilla confessionis. Later he

wrote:

“My father adopted the name of Mason on landing in

New Orleans when I was 11, his object being

avoidance of the prejudice which obtained against

the Irish. Don’t split on me till I’m dead, and even

then I would rather you didn’t give the name, it’s

so infernally Milesian, and they’d say that all the

faults of the race went with it, particularly love

of drink and laziness. I have them both myself!”

The real James Mason was unknown and incomprehensible

to the huge majority of the people with whom he

associated, and their estimate of him, their measuring

his bushel by means of their pint-pots, is ludicrous

indeed. It may be that in the time to come this column

may present a few extracts from Mason’s letters, of

which about 400, some of them very long, regular

essays, addressed to the writer, are available.

Mason was a great letter-writer, and when addressing

people with whom he was in sympathy, was apt to let

himself go.

And thus I have strayed from the subject of Frank

Marshall to one of the “sceptred heroes who still rule

our spirits from their urns”. No matter. The Masonic

secret should be interesting. Perhaps Mason had other

confidants. Yet he was never one of those who wear

their hearts on their sleeves for daws to peck at.

One thing I wish to place on record. In money

matters; in straightness; in all things where honour

was a factor, I ever found James Mason the very soul

of integrity; and in this respect as well as

intellectually, immeasurably superior to some of the

men who smiled upon him patronizingly, and held him in

contempt because of his poverty and the well-known

weakness which all his friends deplored.’

James Mason

6127. Alleged suicide attempt by

Alekhine (C.N.s 790 & 3842)

Alexander Alekhine

Jeremy Silman (Los Angeles, CA, USA) asks whether any

further details are available regarding Edmond Lancel’s

claim on pages 1152-1153 of the April 1946 issue of L’Echiquier

Belge that in 1922 Alekhine tried to stab himself

to death in the lobby of the Hotel Corneliusbad in

Aachen.

Afterword:

As reported in an endnote on page 263 of Chess

Explorations, in C.N. 862 C.D. Robinson (Toronto,

Canada) commented:

‘Alekhine is alleged to have stabbed himself about

3 a.m. after celebrating his birthday. The actual

date would be either 20 October or 1 November,

according to whether he kept his birthday on the

Russian date of 19 October or the Western date of 31

October. This allows a maximum of 24 days in which

to recover from a serious wound and to travel from

Aachen to Vienna for a tournament beginning on 13

November ... Lancel is wrong when he claims that

Vienna, 1922 was Alekhine’s worst result between

Scheveningen, 1913 and Nottingham, 1936. The earlier

limit should be Vilna, 1912 (the All-Russian

Tournament).’

C.N. 1854 offered an excerpt from the reminiscences of

Francisco José Pérez in the March 1989 Revista

Internacional de Ajedrez (page 14). Regarding

Alekhine he said:

‘While playing in a tournament in Sabadell in 1945,

Alekhine said that he did not have the courage to

commit suicide; his wife had written to him saying

that she did not want to hear from him any more.’

Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) notes that although

the run of the Swedish magazine Schackvärlden

from 1923 to 1945 extended to 22 volumes (the first of

which featured November 1923-December 1924), only the

last two years were indexed, in the respective

December issues. However, page 138 of the October 1946

Sjakkliv, a Norwegian journal, reported that

the problemist Alf O. Evang had drawn up an index for

Schackvärlden (158 densely typewritten pages

in four parts, covering 1923-28, 1929-33, 1934-38 and

1939-43) and was prepared to duplicate his

manuscript if enough orders were placed. Our

correspondent asks whether any copies of the index can

be found.

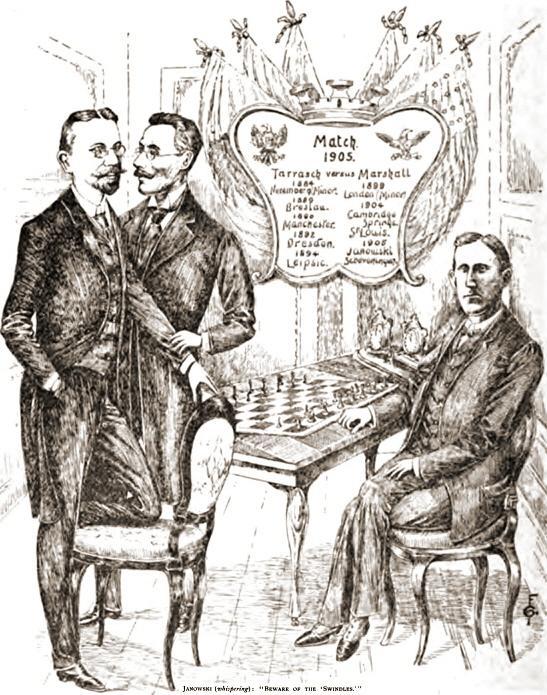

On the basis of Janowsky’s weekly chess column in Le

Monde Illustré (11 February to 18 March 1905),

as well as La Stratégie of 20 February and 17

March 1905, we list the total times taken by Marshall

and Janowsky in their 17-game match in Paris.

Marshall, who won +8 –5 =4, had White in the

odd-numbered games:

1: 4.14 – 4.11;

2: 2.30 – 2.30;

3: 2.48 – 2.13;

4: 3.48 – 4.12;

5: 3.00 – 2.48;

6: 3.19 – 3.00;

7: 2.00 – 2.12;

8: 2.05 – 1.57;

9: 4.24 – 4.21;

10: 4.14 – 4.31;

11: 3.43 – 3.46;

12: 3.10 – 2.40;

13: 4.12 – 4.40;

14: 3.20 – 2.18;

15: 2.52 – 4.57 (Le Monde Illustré) or

4.37 (La Stratégie);

16: 1.49 – 3.00;

17: 3.03 – 4.35 (times omitted by Le

Monde Illustré).

What is the soul of chess? Among the

possibilities are pawns (Philidor), combination

(Maróczy), the centre (Alekhine) and tempo (Tarrasch).

The corresponding citations can be found in the Factfinder, and we

now add the following:

- ‘... if either player had the privilege of making

two moves in succession, it is evident that he would

have no difficulty in winning the game. To gain this

one move, – with all due deference to the shade of

Philidor, – and not the play of the pawns, is the soul

of chess.’

Source: The Major Tactics of Chess by

Franklin K. Young (Boston, 1909), page 269.

- ‘Beautiful combination play is the soul of chess.’

Source: The Joys of Chess by Fred Reinfeld

(New York, 1961), page 117.

- ‘... error is the soul of chess.’

Source: Chess Players’ Thinking by Pertti

Saariluoma (London, 1995), page 153.

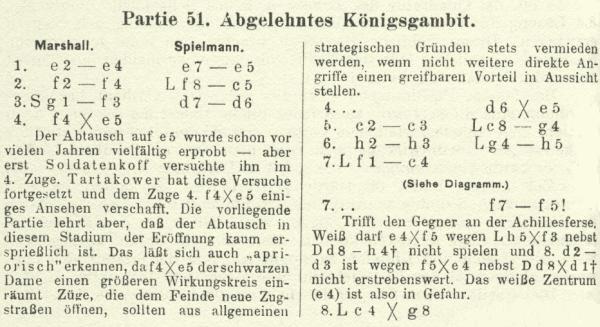

6131. Photographs of Eliskases, Pirc

and Spielmann

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) has submitted

from his collection two photographs taken at Poděbrady,

1936:

Erich Eliskases

Vasja Pirc (and, on his

left, Bedřich Thelen)

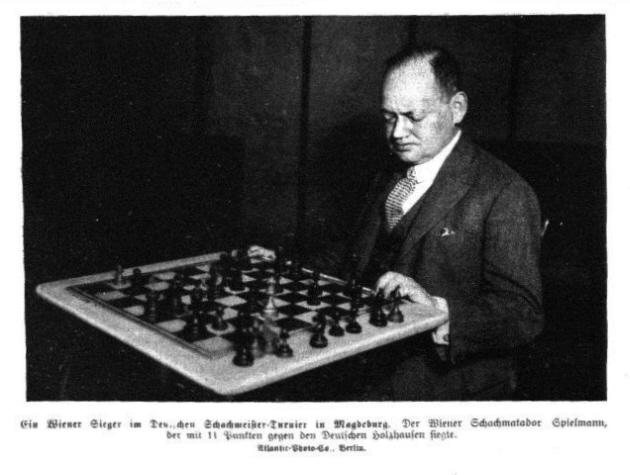

Our correspondent has also provided a photograph of

Rudolf Spielmann at Magdeburg, 1927, from page 4 of Wiener

Bilder, 7 August 1927:

Addition on 8

August 2025:

It appears that the Spielmann photograph was taken in

Berlin in November 1926. See C.N. 12187.

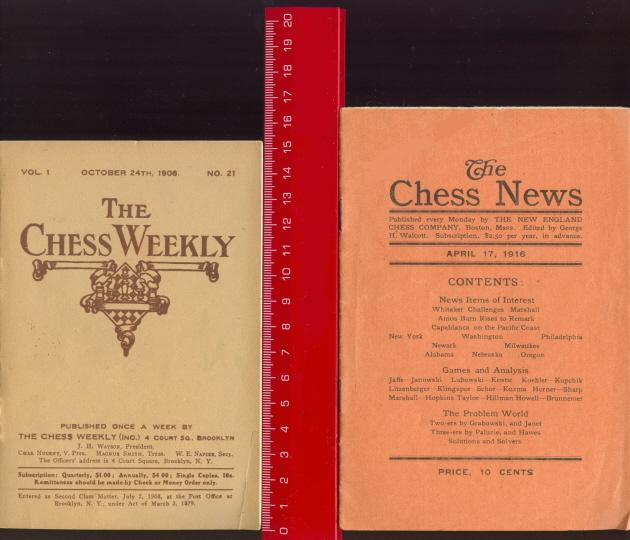

6132. Small magazines

Page 398 of the August 1936 BCM announced

receipt of the first issue of Ajedrez Chileno,

‘which has the distinction of being in format the

smallest chess magazine, we believe’. Page 39 of the

January-February 1937 L’Echiquier stated that

the size of the Chilean magazine (which we have not

seen) was 13cm x 18cm, but that is substantially larger

than two earlier publications that come to mind:

C.N. 4244 showed our smallest chess book (approximately

6cm x 4cm).

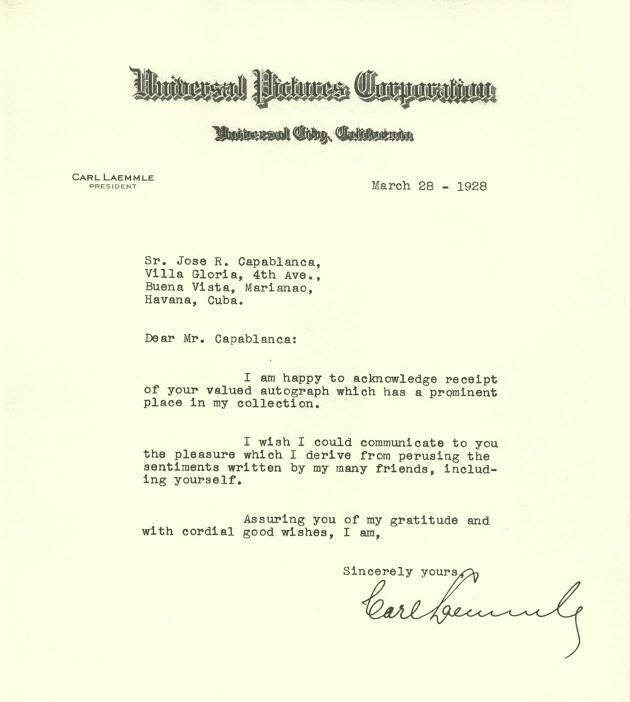

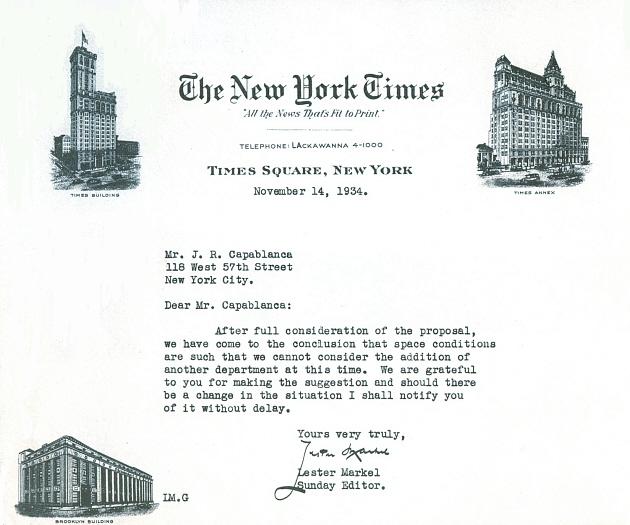

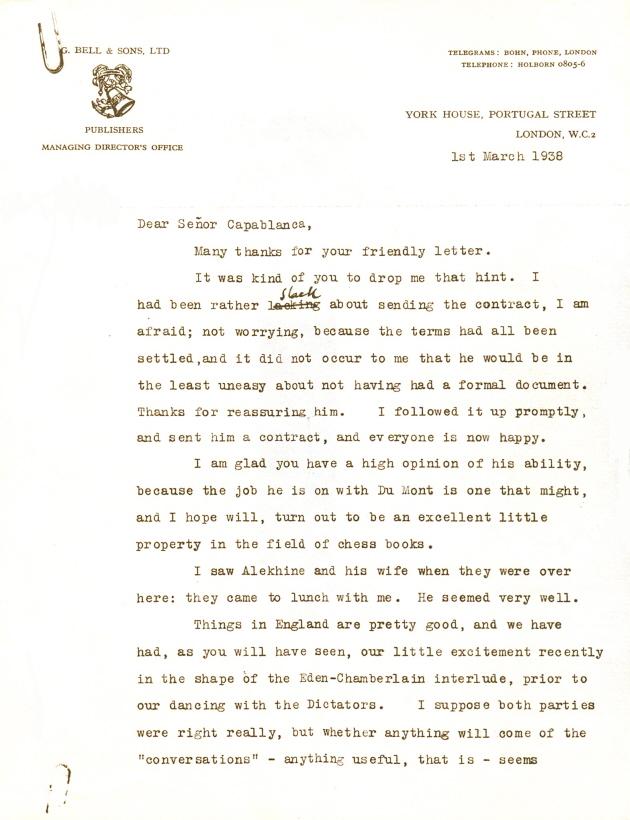

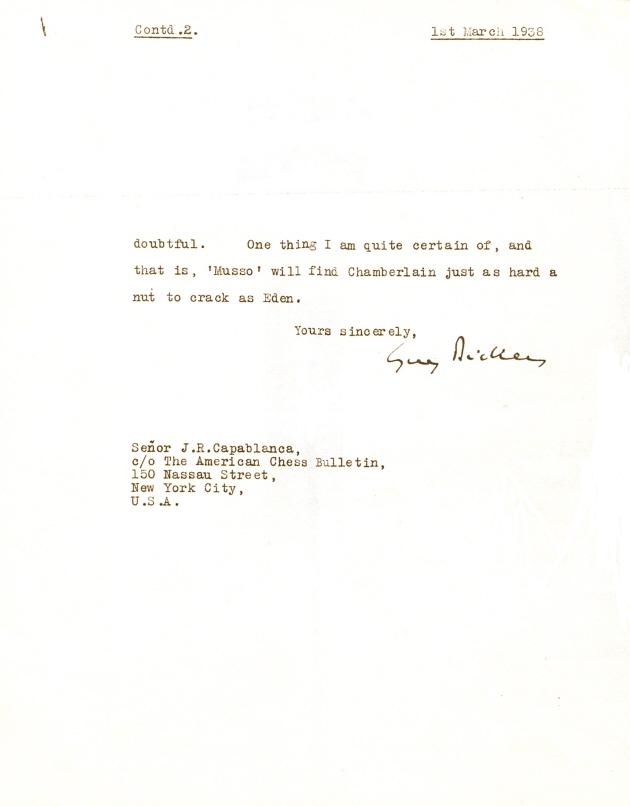

Our collection includes copies of many letters

addressed to Capablanca, and three are reproduced

below:

6134.

Pollock

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) notes that in the Preface

to her book Pollock Memories (Dublin, 1899) F.F.

Rowland mentioned among her sources ‘interesting MMS.

books, belonging to Mr Pollock, which contained about

3,000 games entered by himself, and played by Masters

and distinguished amateurs, with critical remarks by Mr

Pollock’. Our correspondent asks whether this material

is known to have survived.

The photograph in C.N. 6125 came from page 195 of CHESS,

17 May 1957:

Paul Dorion (Montreal, Canada) mentions that the Pirc

photograph from Poděbrady, 1936 shows the position

after Black’s 36th move in the game against Karel

Skalička (see page 45 of the tournament book).

6137. Rosenthal and Janowsky

The following photographs appeared in Le Monde

Illustré on, respectively, 20 September 1902 (page

288) and 27 September 1902 (page 312):

Samuel Rosenthal

Dawid Janowsky

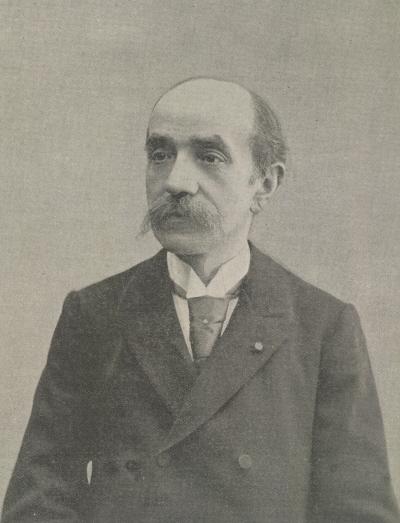

6138. Soldatenkov

Three games involving the little-known player

Soldatenkov were given in 1000 Best Short Games of

Chess by I. Chernev (New York, 1955): victories

against an anonymous player and F.J. Marshall (in 17 and

21 moves respectively and both published on page 433 of

the November 1928 BCM) and The Consultation Game

That Never Was. Another brilliancy is on pages

43-44 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

Vassily Soldatenkov – N.N.

Occasion?

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 d3 d6 5 Be3 Bd7 6 Nbd2 d5

7 exd5 Nxd5 8 Qe2 Bd6 9 Ne4 Bg4 10 O-O-O O-O 11 h3 Bh5

12 g4 Bg6 13 h4 h5 14 Nfg5 hxg4 15 h5 Bxe4 16 Nxe4 f5 17

Bc4 Ne7 18 Bg5 c6

19 h6 g6 20 h7+ Kh8 21 Bh6 fxe4 22 dxe4 Rf7 23 Qxg4 Nf6

24 Qg5 Ned5 25 exd5 cxd5 26 Qxg6 Qc7 27 Bxd5 Nxd5

28 Qg8+ Rxg8 29 hxg8(Q)+ Kxg8 30 Rdg1+ Rg7 31 Rxg7+

Qxg7 32 Bxg7 Kxg7

33 Rd1 and wins.

Source: The Times Literary Supplement, 24

October 1902, page 320.

Below are some further neglected games:

Vassily Soldatenkov – Fürst G.

St Petersburg, 24 April 1902

(Remove White’s queen’s knight.)

1 e4 e5 2 d4 Nc6 3 dxe5 Nxe5 4 f4 Ng6 5 Nf3 Bb4+ 6 c3

Ba5 7 Bc4 N8e7 8 f5 Nf8 9 Bxf7+ Kxf7 10 Ne5+ Ke8 11 Qh5+

g6

12 f6 Ne6 13 f7+ Kf8 14 Bh6+ Ng7 15 Qh4 Nc6 16 Bg5 Ne7

17 Rf1 d6 18 Bxe7+ Qxe7 19 Nxg6+ hxg6 20 Qxh8 mate.

Source: Deutsche Schachzeitung, July 1902,

pages 215-216.

Vassily Soldatenkov – A.J. Barasov

St Petersburg (date?)

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 Qe2 Nf6 3 f4 Bc5 4 Nf3 O-O 5 d4 Bb6 6 e5 Nd5

7 c4 Ba5+ 8 Kf2 Ne7 9 Nc3 c6 10 g4 d6 11 Be3 dxe5 12

dxe5 Bb6 13 Rd1 Bxe3+ 14 Qxe3 Qb6 15 c5 Qxb2+ 16 Rd2 Qb4

17 Bd3 Nd5 18 Nxd5 exd5 19 Rb1 Qa5

20 Bxh7+ Kxh7 21 Ng5+ Kg8 22 Qd3 f5 23 Qh3 Qxd2+ 24

Kg1 Re8 25 Qh7+ Kf8 26 Qh8+ Ke7 27 Qxg7+ Kd8 28 Qf6+ Re7

29 Nf7+ Ke8 30 Nd6+ Kd7 31 Qxf5+ Re6 32 Qf7+ Re7 33 e6+

Kc7 34 Qxe7+ Nd7

35 Qxd7+ Bxd7 36 Rxb7+ Kd8 37 Rxd7 mate.

Source: Page 171 of Traité du jeu des échecs by

J. Taubenhaus (Paris, 1910). Brief notes by Soldatenkov

were included.

Vassily Soldatenkov – Frédéric Lazard

Café de la Régence, Paris, 9 January 1912

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 dxc4 5 Bg5 Be7 6 e3 Nd5

7 Bxe7 Nxc3 8 bxc3 Qxe7 9 Bxc4 O-O 10 O-O b6 11 Bd3 Nd7

12 Qc2 g6 13 Be4 Rb8 14 Qa4 a5 15 Bc6 Rd8 16 Rfd1 Bb7 17

Bxb7 Rxb7 18 Qc6 Ra7 19 Rab1 Qd6 20 Qe4 Nf6 21 Qh4 Qe7

22 e4 Kg7 23 Rb5 c6 24 Rxb6 Qc5

25 e5 Qxb6 26 exf6+ Kf8 27 Qxh7 Ke8 28 Ne5 Qc5 29 Qg8+

Qf8 30 Qxf8+ Kxf8 31 Nxc6 Resigns.

Source: La Stratégie, January 1912, pages

23-25. The game was annotated by ‘A.G.’, who concluded:

‘La partie a été un peu légèrement jouée par le

jeune champion de la Régence et ne donne pas la

mesure de sa force. Par contre, le brillant amateur

russe l’a conduite avec une précision et une logique

impeccables. Nous considérons Mr Soldatenkoff comme

un des plus forts joueurs de Paris. Personne n’a

plus de science ni de brio.’

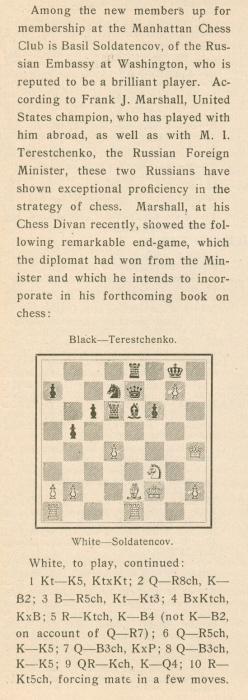

From page 224 of the American Chess Bulletin,

November 1917 (an item headed ‘Ending between Russian

Diplomats’):

A computer check shows that White missed a number of

faster wins.

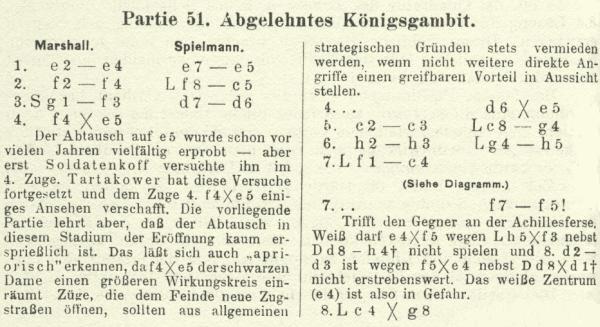

Soldatenkov’s name became associated with 1 e4 e5 2 f4

Bc5 3 Nf3 d6 4 fxe5 (the ‘Soldatenkov Attack’ or

‘Soldatenkov Variation’) after the following appeared on

page 124 of the Carlsbad, 1907 tournament book by Marco

and Schlechter:

A number of Soldatenkov’s early games in Russia,

together with much other material, were given in a small

monograph on him, Tajemný Námořník by V. Čarušin

(Brno, 1998). The New York Times (15 October

1917, page 16) reported that a Marshall/Soldatenkov v

Janowsky/Jaffe consultation game had just begun (‘The

contest will probably extend over the greater part of

the week. Marshall and Soldatenkov, playing the white

pieces, elected a queen’s pawn opening, to which the

rival pair replied with knight to king’s bishop

third.’). Further information would be welcome. Page 210

of the December 1921 American Chess Bulletin

gave the score of an 18-move draw by Soldatenkov against

Perkins which was played in a Metropolitan League match

between the Marshall Chess Club and the Brooklyn Chess

Club. A loss by Soldatenkov to Zirn in the Metropolitan

Chess League was published on page 25 of the February

1922 American Chess Bulletin. More details are

sought about the game ending ‘Soldatenkov-Wolf, Berlin,

1925’ given on pages 119-120 of The Joys of Chess

by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1961). Soldatenkov’s 21-move

victory over Marshall referred to at the beginning of

the present item was published by H. Wolf on pages

300-301 of the September-October 1928 issue of Kagans

Neueste Schachnachrichten. Clarification of the

circumstances of the game, together with notes by

Soldatenkov himself, appeared on pages 197-200 of the

June 1929 issue. A lengthy article by Soldatenkov was

published on pages 221-226 of the July 1929 Kagans

Neueste Schachnachrichten. It discussed a recent

victory over A. Zimine in the light of a Bogoljubow v

Euwe game (the seventh contest in their second match,

played in Amsterdam on 2 January 1929 – see pages 53-54

of the February 1929 Wiener Schachzeitung).

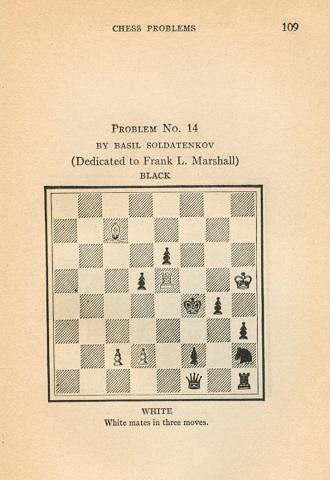

Below is page 109 of the revised edition of Mitchell’s

Guide

to the Game of Chess by David A. Mitchell

(Philadelphia, 1920):

Soldatenkov also has a bearing on the origins of the Marshall Gambit

in the Ruy López. At New York, 1918 Marshall played

8...d5 twice, against Capablanca and Morrison. Regarding

the latter game it was pointed out on page 276 of the

December 1918 American Chess Bulletin (under the

heading ‘Duplication of Game after 17 Years’) and on

page 21 of the tournament book that a game Sittenfeld v

Soldatenkov, Paris, 1901 had followed Morrison v

Marshall as far as move 18 (when Soldatenkov played

...Bd6 instead of ...gxf6). Whereas Marshall’s victory

took 84 moves, Soldatenkov won in 25.

Without reference to these American sources, the

Sittenfeld v Soldatenkov game was given by Kevin

O’Connell on page 186 of the April 1980 BCM (in

K. Whyld’s ‘Quotes & Queries’ column). It was stated

that O’Connell had found the game in La Stratégie

for 1901, but we do not see it there.

On pages 314-315 of the July 1987 BCM we quoted

from, and commented on, the above-mentioned American

Chess Bulletin item. Page 612 of the November 1999

BCM (also in the ‘Quotes & Queries’ column)

referred to the difficulty in finding biographical

information about Soldatenkov (whose birth details were

given as 14 July 1879 at Tsarskoye Selo – as mentioned

on page 3 of the booklet on Soldatenkov by

Čarušin/Charushin).

The lack of information about Soldatenkov (e.g. where

and when he died) is particularly strange in view of his

prominence as a diplomat on both sides of the Atlantic.

A lengthy political article on page 12 of the New

York Times, 20 October 1918 included the

following:

‘Basil Soldatenkov, standing six feet in his socks

and as hard as nails, his deep-set gray eyes looking

you straight through from beneath the ledge of a

massive brow crowned with waving light brown hair, is

a comparatively young man to have had the experiences

and to have shouldered the responsibilities which have

been his.

He is, perhaps, five and thirty, and by natural

mental inclination a mathematician and electrical

engineer. On leaving the university, it was his

intention to make scientific research his life work,

but circumstances led him, first, to try for and win a

commission in the Russian navy, and later to enter the

Russian Diplomatic Corps.

Mr Soldatenkov served the Imperial Russian Government

in nearly every capital of Europe. There are few men

living who have as intimate a personal acquaintance

with the great diplomats of the world. He came to this

country on a special mission from the Kerensky

Government.’

It will be noted that his forename was given as

‘Basil’, i.e. the anglicized version of Vassily.

However, page 63 of the March 1918 American Chess

Bulletin referred to ‘Boris Soldatenkoff, the

Russian envoy’. Because of German transliteration, the

initial of his forename was sometimes recorded as W

(‘Wassily’). The index for the 1907 volume of Deutsches

Wochenschach (page 483) had ‘Soldatenkow, W.W. (St

Petersburg)’.

Below is an extract from the New York Times, 18

March 1920, page 11:

‘Mr and Mrs Basil Soldatenkov yesterday surprised

their relatives and friends by announcing they had

been married in Newark, NJ on Tuesday. Mrs Soldatenkov

was formerly Miss Madeleine Reese, niece of Martin

Vogel, Assistant United States Treasurer, and Mrs

Vogel, with whom she had resided since the death of

her mother six years ago.

Mr Soldatenkov, who was a special envoy of the

provisional Government of Russia, had been attentive

to Miss Reese for some time, but Mr and Mrs Vogel

withheld their consent to the marriage, owing chiefly

to the disparity of their ages, their niece being only

20 years of age and Mr Soldatenkov about 17 years her

senior ...

Mr Soldatenkov has been married before. His first

wife was the Princess Gotchakoff of Russia, from whom

he was divorced last November.

Mr Soldatenkov was Under Secretary of State in Russia

under the Milyoukof régime. He met and took charge of

Elihu Root and the American Mission when it arrived in

Russia, and returned here with the Mission. On his

arrival he was thanked personally by President Wilson

and Mr Root and was presented with a cigarette case

bearing an inscription in acknowledgment of his

services to the American Mission.’

The above two references to Soldatenkov in the New

York Times suggest that he was born in or around

1883. It was subsequently reported by the newspaper (21

December 1928, page 13, and 11 October 1933, page 27)

that the couple were divorced in Nice in October 1928.

On 10 October 1933 the marriage took place in London

between Madeleine Soldatenkov and ‘Baron Constantine

Nicolai Stackelberg, whose father, Baron Nicolai

Stackelberg, was a master of ceremonies at the court of

the late Czar Nicholas of Russia’.

The Family

Search website produces the information that

‘Vasilij Vassilievich Soldatenkov’ was born circa

1869 in ‘Tachanj, Pltv, Ukraine’ and that he married

‘Elena Konstantinovna, Princess Gorchakov’ on 20 January

1901. However, there is also an entry for ‘Basil

Soldatenkow’, born in Moscow on 14 June 1877.

The search for biographical details about Soldatenkov

continues, and for the time being we conclude with a

quiz question arising from one of his early games:

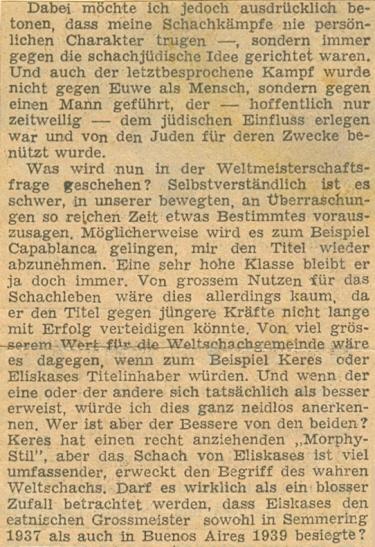

White to move. What is the fastest

win?

6139. Marini v Spassky

Jake Freeman (Salt Lake City, UT, USA) raises the

subject of L. Marini v B. Spassky, Mar del Plata, 1960,

which appears in databases as follows: 1 c4 Nc6 2 Nc3

Nf6 3 g3 e5 4 Bg2 Bc5 5 a3 a5 6 e3 O-O 7 Nge2 Re8 8 d3

d6 9 h3 Bd7 10 Bd2 Qc8 11 Qc2 Ne7 12 Ne4 Nxe4 13 dxe4

Be6 14 Nc1 a4 15 Nd3 Nc6 16 Nxc5 dxc5 17 f4 f6 18 f5 Bf7

19 g4 Rd8 20 Bf1 g5 21 h4 h6 22 Bc3 Kg7 23 Qh2 Rh8 24

Be2 Qe8 25 Kf2 Rd8 26 Qg3 Qe7 27 Rh3 Na7 28 Rah1 Nc8 29

Qh2 Rhg8 30 hxg5 hxg5 31 Rh7+ Kf8 32 Bd1 Qd7 33 Bc2 Nd6

34 Kf3 Nxc4 35 Rd1 Nd6 36 Qh6+ Ke7 37 Rd5 Qb5 38 Bd3 Qb3

39 Be2 Drawn.

Regarding the diagrammed position Mr Freeman comments:

‘Instead of 39 Be2, there is 39 Bxe5 fxe5 40 Qe6+

Kf8 41 Rxf7+ Nxf7 42 Bc4 Qxc4 43 Rxd8+ Nxd8 44 Qxc4,

winning easily. If Black plays 42...Re8, then 43

Qxf7+, followed by 44 Rd7+ and mate next move.’

To our list of ‘Mates missed’ in the

Factfinder

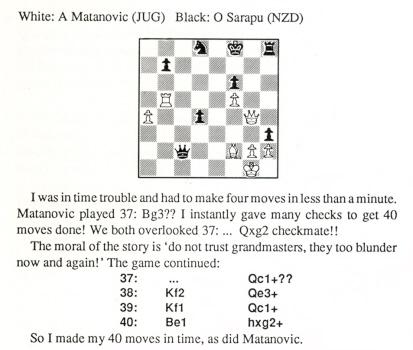

Frederick S. Rhine (Park Ridge, IL, USA) adds the

account on page 51 of ‘Mr Chess’ The Ortvin Sarapu

Story by Ortvin Sarapu (Wainuiomata, 1993):

Matanović eventually agreed to a draw after Black’s

54th move.

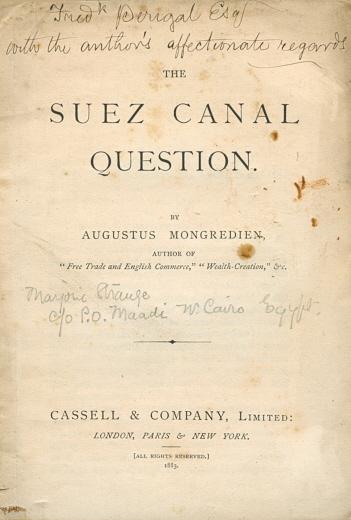

6141. Mongredien (C.N. 4895)

Below from our collection is another inscribed title

page of a non-chess book by Augustus Mongredien:

The Suez Canal

Question (London, 1883), inscribed to Frederick

Perigal

From Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada):

‘C.N. 5048 quoted G.A. MacDonnell, who said that

the remarkable Campbell v Barnes match (in which

Campbell won 7-6 after being down 1-6) took place

in 1861. However, page 100 of the Chess

Player’s Chronicle, 1859 stated that the match

occurred in 1858.’

In this game White played without his queen but made

the first two moves: 1 e4 ... 2 d4 d5 3 exd5 Qxd5 4

Nc3 Qxd4 5 Be3 Qe5 6 O-O-O Nc6 7 Nf3 Qa5 8 Rd5 Qb4 9

Nb5 e6 10 Nxc7+ Ke7 11 Bc5+ Kf6 12 Ne8+ Kg6 13 Rg5+

Kh6 14 Be3 Qe7 15 Rxg7+ Kh5 16 g4 mate.

The victor was Adolf Albin, against an unnamed

opponent, and the score was given on page 180 of 1000

Best Short Games of Chess by Irving Chernev

(New York, 1955). No place or date was specified, but

we note that the game was published on pages 366-367

of La Stratégie, 15 December 1901, having been

played a few days previously at the Cercle Philidor in

Paris.

6144. Soldatenkov (C.N. 6138)

Vitaliy Yurchenko (Uhta, Komi, Russian Federation)

reports that page 43 of the Russian edition of the

monograph by V. Charushin (Omsk, 2000) reproduced

Soldatenkov’s Полный послужной список (complete service

record), dated 13 January 1913. It gave his birth-date

as 14 July 1879 (old style).

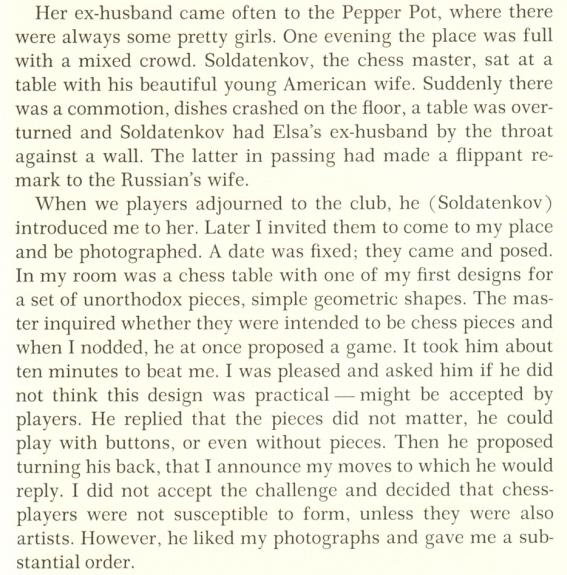

We have found a passage about Soldatenkov on page 99 of

Self Portrait by Man Ray (Boston and Toronto,

1963). Elsa Schiaparelli has just been mentioned.

Page 243 reproduced the well-known (indoor) photograph

of Man Ray playing chess with Marcel Duchamp (Paris,

1956).

6145. Forced mate (C.N. 6138)

This position (White to move) at the end of C.N. 6138

came from page 52 of the 15 February 1898 issue of La

Stratégie, which stated that White (Soldatenkov)

gave mate in eight moves. The solution on page 119 of

the 15 April 1898 magazine was 1 Qh7+ Kxh7 2 gxf8(N)+

Kh6 3 Rh7+ Kg5 4 h4+ Kf5 5 e4+ Ke5 6 Nc4+ Kd4 7 Ne2+

Kxc4 8 b3 mate.

However, it was also pointed out by La Stratégie

that two correspondents (Guinet and Buckley) had offered

a quicker finish (4 Nde4+ Kf5 5 Nxd6+ Ke5 6 Nf7+ Kf5 7

e4 mate).

When the initial position was given on page 16 of the

Czech edition of V. Charushin’s booklet on Soldatenkov

(the source being specified as Shakhmatny Zhurnal,

1897, page 357) Black had two additional pieces: a

knight on b7 and a bishop on c4. There is then no mate

in seven, and the fastest mate is the above line ending

in 8 b3.

Jens Kristiansen (Qaqortoq, Greenland) is trying to

ascertain the highest age at which anyone has gained

the grandmaster title for over-the-board play in

regular fashion (and not, for instance, honoris

causa).

A chess bookshop which can be

recommended for its impressive stock and efficient

service is run by Kimmo

Välkesalmi in Helsinki.

6148. Chess prodigies

Christopher Lenard (Bendigo, Victoria, Australia)

writes:

‘Does any comparative study exist of the early

games of chess prodigies, i.e. the games of

youngsters who have a strong natural aptitude but

have not yet been exposed to much formal study? In

particular, I am interested in what similarities, if

any, exist among such players from over the last

century or so. For example, do very strong but

“naïve” (untutored) players tend to spot and exploit

certain types of patterns?’

The subject of chess prodigies has received

surprisingly little treatment in chess literature. For

an historical sweep, only two books come to mind – Great

Games by Chess Prodigies by Fred Reinfeld (New

York, 1967) and Los niños prodigio del ajedrez

by Pablo Morán (Barcelona, 1973) – but neither adopted a

scientific or academic approach. Can readers quote any

articles covering the specific field mentioned by our

correspondent or dealing authoritatively with the more

general topic of chess Wunderkinder? We hope to

build up a bibliography at the end of the Chess Prodigies

article.

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) comes this sketch

on page 438 of the November [sic – it was

mistakenly headed ‘October’] 1905 BCM:

Caleb Wright (Ohauiti, Tauranga, New Zealand) asks

for solid information about reports that the Soviet

computer KAISSA helped David Bronstein in an adjourned

game in 1975.

Firstly, we quote a passage from page 128 of How

Computers Play Chess by D. Levy and M. Newborn

(New York, 1991):

‘The first occasion on which a program’s ability to

play certain endgames perfectly was useful to human

players was at a Soviet tournament in 1975. There,

in Vilnius, Grandmaster David Bronstein was able to

use a database created by the KAISSA team to help

him analyze an adjourned game, which he subsequently

won. This was the ending of queen and knight’s pawn

(g-pawn or b-pawn) against queen, the most difficult

of all queen and pawn endings.’

Such an ending, we note, occurred in Bronstein’s game

in Vilnius against Karen Grigorian. More details, from

primary sources, of the computer’s involvement will be

appreciated.

For other information on KAISSA, see chapter six of Chess

in the Eighties by D. Bronstein and G. Smolyan

(Oxford, 1982).

Chess Notes Archives

Copyright: Edward Winter. All

rights reserved.

|