Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [133] | next >> | Current column |

9401. The dark side of Fischer (C.N.s 9245, 9252 & 9338)

Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam still cannot bring himself to correct the record in New in Chess after cold-bloodedly deceiving his readers about us on page 16 of the 3/2015 issue.

9402. A claim of pre-eminent ignorance

Horacio Paletta (Buenos Aires) draws attention to an interview by Luciano Ciruzzi in Página 12, 28 July 2015 in which the grandmaster Hugo Spangenberg claimed to know less than anybody else about chess history and games (‘Soy la persona que menos sabe de historia de ajedrez y que conoce menos partidas’).

9403. Steinitz’s early years (C.N. 9200)

From Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany):

‘A number of relevant documents can be found in an online database of the National Archives of the Czech Republic in Prague, including conscriptions, which are police registration forms.

There is a conscription concerning Wolf Steinitz for the years 1855 and 1856, and the fact that he had his own form shows that he was not living with his family (see the general description). The entries in the third, fifth and sixth columns identify him as Wolf Steinitz, born in 1836 in Prague. (It was usual to omit the initial digit 1 in the year, to save space.) The first entry was made on 20 January 1855, and Steinitz was then living in the house 196/5. The second number describes the quarter/district of Prague, and 5 (or the equivalent V) means Josefov (in German: Josefstadt), which was formerly the Jewish ghetto of Prague.

The next document to consider is an extract from a Prague address book for 1859 (Adreßbuch der Königlichen Hauptstadt Prag, etc. by Nikolaus Lehmann, (Prague, 1859), page II-31.)

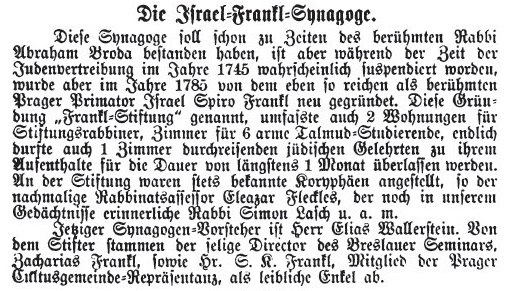

The house 196 was in the “Rabbinergasse”, and its owners were the “Israel Frankl’sche Stiftung” and several individuals. The “Stiftung” is of particular interest:

Above, from page 102 of the Jahrbuch 1893-94 für die israelitischen Cultusgemeinden Böhmens, etc. (Prague, 1893), is a description of the foundation: apart from a small synagogue, there were two apartments for rabbis of the foundation, six rooms for poor Talmud students, and also one room for Jewish scholars passing through Prague. It was named after its founder, Israel [Simon, Spiro] Frankl, who was “Primator” in the second half of the eighteenth century. I believe that this means that Frankl was a kind of mayor of the Jewish quarter or ghetto, because the Czech word “primátor” means mayor).

The address 196/5 is related to the question of whether Steinitz was a Talmud student in his youth. About a year before his death, the Jewish Chronicle published an article “A Chat with Steinitz” (4 August 1899, pages 12-13). Here is a quote from page 12:

“I asked Steinitz to give me some account of his life. He is descended from a Rabbinical family. The name of his uncle, Lazarstein [sic; Lazar Steinitz], is to be seen on many of the Chumoshin [Pentateuch] published in Prague, where he was the official corrector of the Jewish Press. Prague was Steinitz’s native city. He was born there on 14 May 1836. His grandfather was a Rabbi and celebrated Talmudist. His grandfather’s brother, Sholem Steinitz, was called to Altona to become a Rabbi. Many families of the name Steinitz to be found today in various parts of Germany are descended from Rabbi Sholem Steinitz.

W. Steinitz himself was educated for the Rabbinical profession. At the age of 13 he was acknowledged to be the best Talmudist among the young men in Prague.”

Not every word in that passage is true, but some of the information must be based on Steinitz’s original words. A point of particular interest is that Steinitz was aged 18, and not 13, when the conscription with the address 196/5 was made.

In the fourth column of that conscription, Steinitz was described as “student and son of the master tailor Josef Steinitz, who resides in house 848/1”. In the final column, the word “Einheimisch” means that his home community was Prague. Every Austrian citizen had such a community, which entailed legal implications, e.g. in case of poverty.

On 20 February 1856 Steinitz’s address was changed to 922/2. The figure 2 denotes the quarter “New Town”, which is a little misleading, because it had been founded as early as 1348. The house 922 was in the Mariengasse/Mariánská ulice, which today is Opletalova ulice. (The house, or its successor, can be seen on Google Street View.)

Among the conscriptions there are also two concerning Steinitz’s father. The first one contains information from 1839, whereas the second one begins in 1865. In all three documents, the father’s profession is master tailor (German: Schneidermeister).

The gap between these records can be filled by a folio from a different online database. The Prague City Archives include the Census of the Prague Population (1830-1949).

This document is much more difficult to decipher. It contains entries covering several decades, and the different sets of handwriting are hard to read. It describes the Steinitz family, and the record is therefore stored under the father’s name. In the small column on the very left are many addresses, some of them with years specified. For example, 6/5 in 1837, 195/5 in 1840, 103/5 in 1843, 879/1 in 1850, 842/5 in 1852 and (already known) 848/1 in 1854.

The first person is the father, Joseph Salamon Steinitz, “Schneidermeister”. The third line from the bottom concerns Wolf Steinitz. His birth-date is given correctly as 14 May 1836, and the next column contains a description of his occupation. I am not sure about the first word, which is crossed out, but I think that it is “Schüler” (pupil). However, the second word is clear: “Hauslehrer” (tutor).

The remaining columns of this line are a real challenge. They begin with “in NC 196/5 [1]855”. NC is an abbreviation indicating a house number. So, this states that in 1855 Steinitz was living in 196/5, a fact already known from the above. However, I should like to offer an additional interpretation: both entries show that Steinitz probably left his family in 1855.

The next part of the text is hard to work out, although there is clearly the year, [1]857, which is important for reasons explained below, followed by the word “risidiert” or “residiert”, which means “resides”. Below that text I read “befindet sich in Strakonitz” (“resides in Strakonitz”).

Moreover, two passports are mentioned; one dated 30 June 1857 and the other 6 July 1858. Both were valid for one year, the normal period. The text after the date 30 June 1857 contains the word “Lehrer” (teacher) and, possibly, a description of a place or institution.

It is now necessary to compare these documents with what appeared in Kurt Landsberger’s biography of Steinitz (Jefferson, 1993), and I list some points in the order in which they appear above.

The address 196/5 (or, to be more precise, the numbers 196 and V) appear in the last paragraph on page 7 of Landsberger’s book as a description of a folio, but this is probably a small mistake. The 11 August 1851 document mentioned in that sentence would be very interesting to see. Landsberger discussed there the possibility that Steinitz left his family at the age of 15.

The profession of Steinitz’s father is discussed on page 4 (in the paragraph which begins “The death notice indicated ...”), and all sources confirm Landsberger’s point: the father was a tailor, but not an ironmonger (see Zmatlik’s text on page 6).

Among the many addresses of the family there is no record of what Landsberger calls “Goldrichgasse” (see page 6, in Zmatlik’s text) or “Goldrich Street” (page 8). The name of the street is given differently in several nineteenth-century sources, Golčische Gasse, Goldrichs Gasse, Goldreichsgasse, etc, but only the houses 12-15/V belonged to it.

When Wilhelm Steinitz applied to study at the Polytechnic in Vienna, he mentioned three years of tutoring. Landsberger wrote (in the middle of page 16), “without indicating whether William was tutored or did the tutoring”. That point can be answered now.

Strakonitz’s Czech name is Strakonice. It is a town about 100 km south-west of Prague. At the bottom of page 7 Landsberger wrote a sentence unsupported by any particular reference:

“In 1855 his residence was no longer Prague, but Strakonici [sic].”

The year 1855 is questionable, because in the census document Strakonitz is mentioned after an entry referring to 1857.

Landsberger referred to both passports at the bottom of page 15, and claimed that for some reason Steinitz stayed in the Prague area. However, a passport or “Heimatschein” was necessary to travel, and it seems probable that Steinitz needed the first one to go to Strakonitz.’

9404. Møller Attack (C.N. 6780)

Position after 17 Bf8-e7

In a discussion of this position from Lasker’s Manual of Chess C.N. 6780 showed that editions published during Lasker’s lifetime stated that White’s next move would be 18 Bf6, whereas the edition brought out by Fred Reinfeld (Philadelphia, 1947) altered it to 18 Bg5.

Now, Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) points out that in the 1960 Dover re-issue of Reinfeld’s edition the move Bg5 was changed back to Bf6. See page 71.

9405. Chess by telephone (C.N. 9386)

It is not intended to chronicle systematically or exhaustively the topic of chess by telephone, but Marek Soszynski (Birmingham, England) draws attention to an article on pages 18-19 of the June 1962 issue of the Wesleyan and General Magazine (the staff publication of the Wesleyan and General Assurance Society, Birmingham), which has this illustration:

The magazine stated:

‘Since 1953 [Wesleyan and General] have played five matches by telephone against the Pearl Assurance Company in London, of which we have won three and lost two. The picture shows the start of the latest match played on 27 April, which we won by 5½ to 3½ (4 wins, 3 draws and 2 losses).’

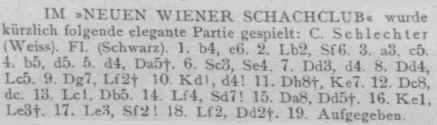

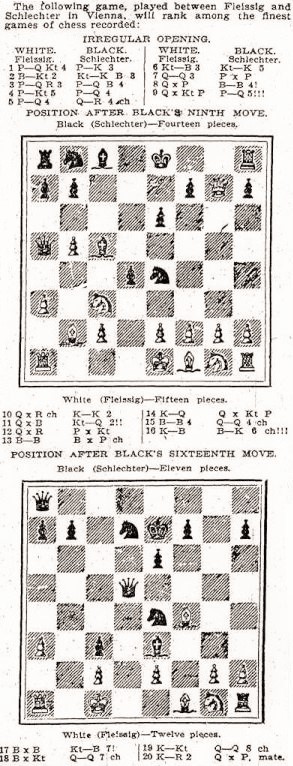

9406. Fleissig v Schlechter

Concerning Fleissig v Schlechter, a clearer version of the game’s appearance on page 841 of Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung of 13 August 1893 (C.N. 6665) can now be given:

Furthermore, Tom Crain (Modesto, CA, USA) reports that when the game was published on pages 59-60 of Lärobok i Schack by Ludvig and Gustaf Collijn (Stockholm, 1903) it was dated May 1895, and ...Nd7 was said to have occurred at move 13.

Remarkably, our correspondent has also found a version of the game in which ...Nd7 was played as early as move 11: 1 b4 e6 2 Bb2 Nf6 3 a3 c5 4 b5 d5 5 d4 Qa5+ 6 Nc3 Ne4 7 Qd3 cxd4 8 Qxd4 Bc5 9 Qxg7 d4 10 Qxh8+ Ke7 11 Qxc8 Nd7 12 Qxa8 dxc3 13 Bc1 Bxf2+ 14 Kd1 Qxb5 15 Bf4 Qd5+ 16 Kc1 Be3+ 17 Bxe3 Nf2 18 Bxf2 Qd2+ 19 Kb1 Qd1+ 20 Ka2 Qxc2 mate.

Source: New-York Daily Tribune, 28 February 1897, part II, page 2.

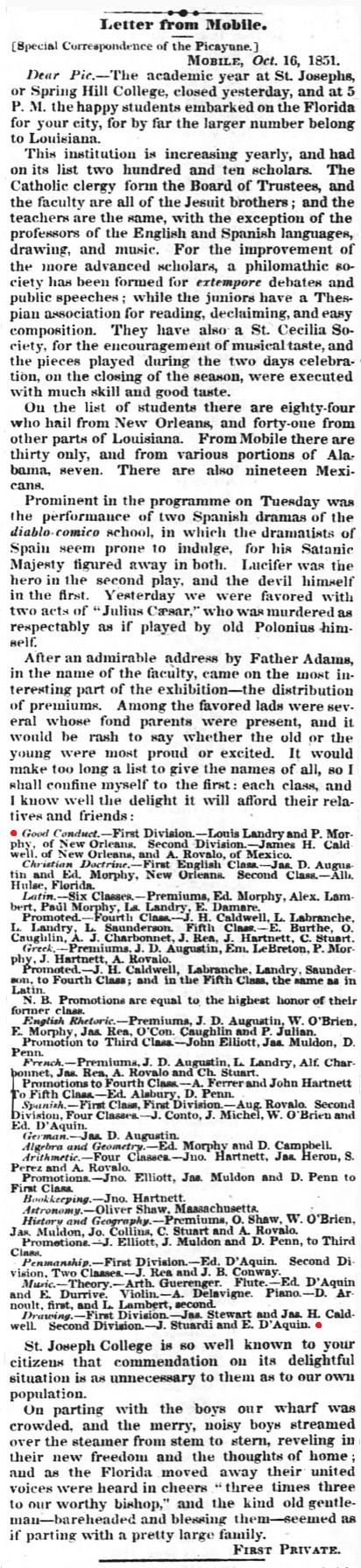

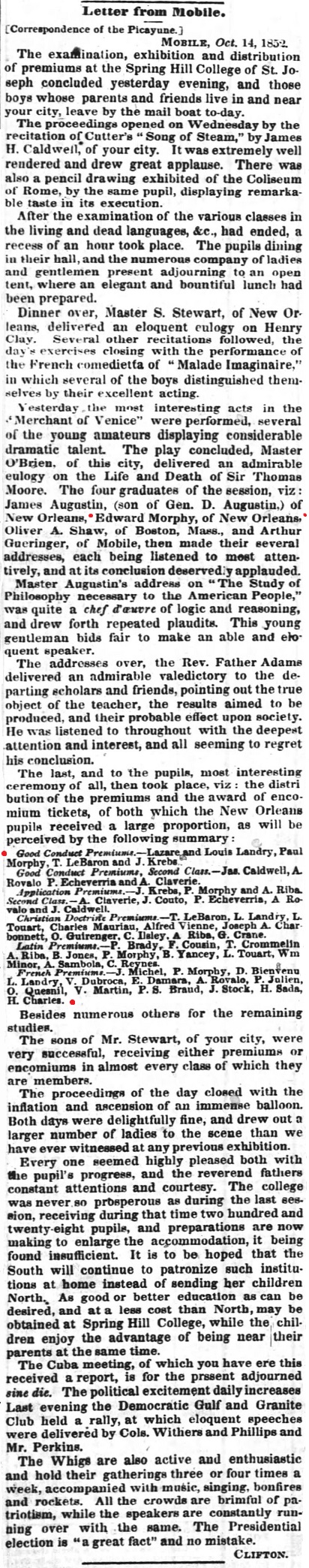

9407. Paul Morphy at Spring Hill College (C.N. 9393)

Patsy A. D’Eramo (North East, MD, USA) provides two columns with earlier mentions of Paul Morphy at Spring Hill College:

Daily Picayune, 17 October 1851, page 1

Daily Picayune, 17 October 1852, page 3.

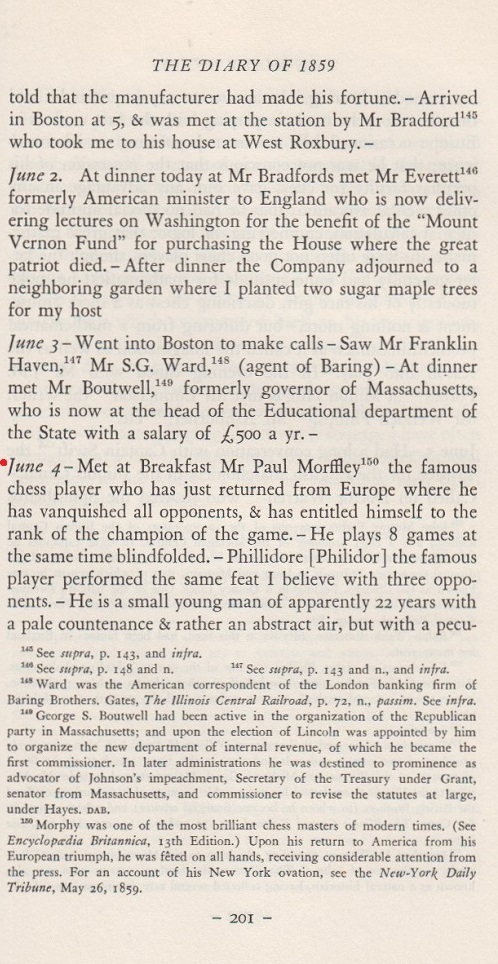

9408. Richard Cobden on Paul Morphy

Two pages (201-202) from The American Diaries of Richard Cobden edited by Elizabeth Hoon Cawley (Princeton, 1952):

We referred to this material on page 28 of the January 1982 BCM.

9409. Quotes

From the main page of the website chessgames.com, 3 August 2015:

The ‘Spielmann’ remark was by Mieses.

From page 41 of the 5/2015 New in Chess (in the ‘Fair & Square’ feature, which has been mentioned in C.N.s 8651 and 8768):

The ‘Bird’ remark was by Conway. The ‘Simon’ remark was by Bonar Law.

9410. Fleissig v Schlechter

Further information of relevance to Fleissig v Schlechter comes from Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany), with regard to the game’s appearance on page 841 of the 13 August 1893 issue of Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung (C.N. 6665). He notes an editorial remark on page 1245 of the 26 November 1893 issue.

This note by Victor Silberer, the Editor, states that the chess column was about to be handed over permanently to Schlechter, who had been conducting it for the past year on a provisional basis.

9411. Christian Hesse

Copying has drawn attention to Christian Hesse’s ‘inaccurate plundering’ of our chess writing and his refusal to correct his gaffes. Our article gives chapter and verse and shows that another victim who has denounced Hesse’s conduct is the excellent Dutch writer Tim Krabbé.

A new book by Hesse has just appeared, Damenopfer (Munich, 2015). In the bibliography on pages 259-264 each entry comprises bare identification of the author, title and publication details. Or, rather, each entry with just two exceptions. In both those cases, on pages 262 and 264 respectively, Hesse has added an identically-worded, unsubstantiated allegation of inaccuracy:

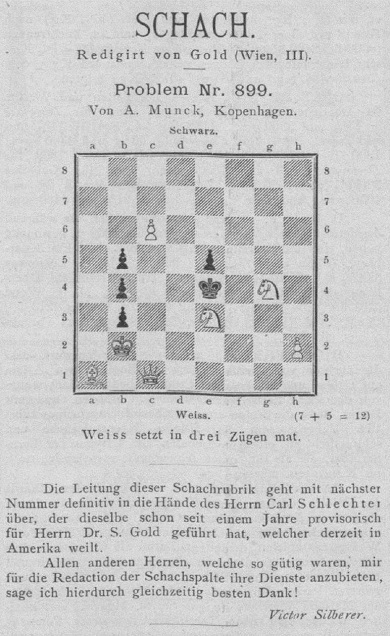

9412. Richmond, 1912

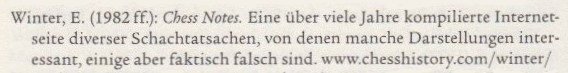

Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) points out a photograph on page 328 of the Illustrated London News, 31 August 1912:

9413. George Bernard Shaw (C.N. 5627)

Any colourful approbation or disapprobation of chess in the output of an eminent literary figure is liable to be quoted as representing his own views even if expressed only by a character in a work of fiction. An example concerning George Bernard Shaw was given in C.N. 5627, and we now show how Fred Reinfeld handled the matter on page 119 of the April 1952 Chess Review:

‘Shaw sneered that chess is “a foolish expedient for making idle people believe that they are doing something very clever, when they are only wasting their time”. Such comments are of little value, for the only information they give us is that their authors fumed at their own execrable chessplaying.’

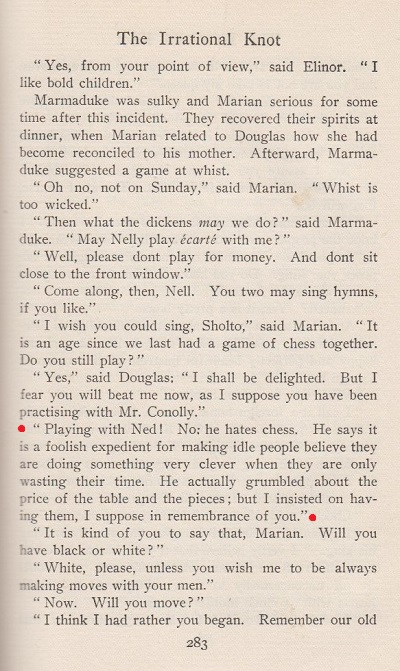

Below is the exact context of Shaw’s words, from page 283 of The Irrational Knot (London, 1905). As stated in the Preface (page vii), he wrote the novel in 1880.

On the Internet, furthermore, it is possible to find the misquotation ‘a foolish experiment’.

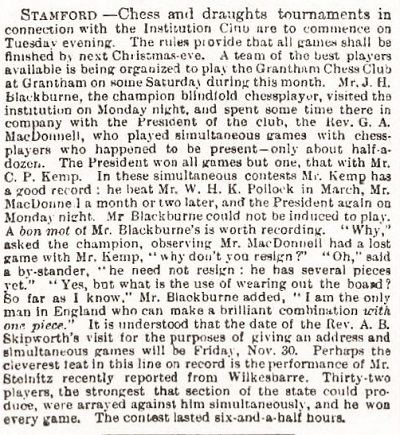

9414. A Blackburne bon mot

From the chess column of A.B. Skipworth on page 6 of the Lincoln, Rutland, and Stamford Mercury, 2 November 1888:

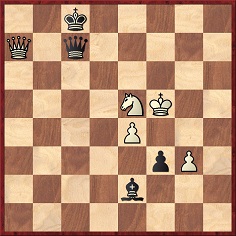

9415. Blackburne v Earnshaw

Steinitz gave high praise to the conclusion of this game (‘played some time back at the Divan’) in his deep annotations in The Field, 6 December 1879, page 781:

Joseph Henry Blackburne – Samuel Walter Earnshaw

London (date?)

Vienna Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 Bc5 4 Nf3 d6 5 Bb5 a6 6 Bxc6+ bxc6 7 fxe5 dxe5 8 Nxe5 Qd4 9 Nd3 Bb6 10 Qf3 Nf6 11 Nf2 Be6 12 d3 O-O 13 Ncd1 Rad8 14 Bg5 Qc5 15 Bxf6 gxf6 16 c3 Qg5 17 O-O Bg4 18 Qg3 Be2 19 Qxg5+ fxg5 20 Re1 Bxd3 21 Kh1 Bc4 22 b3 Be6 23 Re2 Rd7 24 Ne3 Bxe3 25 Rxe3 Rd2 26 Kg1 f5 27 Kf1 f4 28 Rd3 Rd8 29 Rxd8+ Rxd8 30 Rd1 Rxd1+ 31 Nxd1

31...Bf7 32 c4 Bg6 33 Nc3 Kf7 34 Kf2 Ke6 35 b4 Ke5 36 b5 axb5 37 cxb5 Be8 38 a4 h5 39 bxc6 Bxc6 40 a5 Bd7 41 h3 g4 42 hxg4 hxg4 43 g3 f3 44 Ke3 Bc8 45 Nd1 Kd6 46 Kf4 c5 47 Nf2 Ba6 48 Nxg4 Be2 49 Kg5 c4 50 a6

50...c3 (‘Falling into the skilfully laid trap. He relies too much on being able to queen with a ch, and no doubt he overlooked that he had no attack to follow, but actually remained with the inferior game. He should have stopped the P by K to B3; and though his opponent would then also intercede against the advance of the QBP by K to B4, Black had a good chance of drawing subsequently.’) 51 a7 c2 52 a8(Q) c1(Q)+ 53 Kf5 Kc7 54 Qa7+ Kc8 55 Ne5 Qc7 (‘Mr Blackburne’s conduct of the ending is beyond all praise.’)

56 Qa8+ Qb8 57 Qxb8+ Kxb8 58 Ng4 Kc7 59 Kf4 Kd6 60 Ke3 Ke6 61 Nh2 Resigns.

Another game between the two players, at Purssell’s Coffee House:

Samuel Walter Earnshaw – Joseph Henry Blackburne

London (date?)

Three Knights’ Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 g6 4 d4 exd4 5 Nxd4 Bg7 6 Be3 d6 7 Bb5 Ne7 8 O-O O-O 9 Nce2 f5 10 Bc4+ Kh8 11 Nf4 Nxd4 12 Bxd4 Nc6 13 Bxg7+ Kxg7 14 exf5 Rxf5 15 Qd2 Ne5 16 Ne6+ Bxe6 17 Bxe6 Rf6 18 Bb3 c6 19 h3 Qb6 20 Rae1 Raf8 21 Re3 a5 22 a4 Qc5 23 Rc3 Qb4 24 Qg5 b5 25 Ra1 Qd4 26 Qe3 Qxe3 27 fxe3 b4 28 Rd3 Nxd3 29 cxd3 Rf2 30 Bd1 Rxb2 31 Bf3 c5 32 Kf1 b3 33 Ra3 d5 34 Ke1

34...Rxf3 35 gxf3 c4 36 dxc4 dxc4 37 Kd1 Ra2 38 White resigns.

Source: Illustrated London News, 26 June 1880, page 631.

The Rev. Earnshaw’s obituary on pages 98-99 of the February 1888 BCM largely consisted of a quote from the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. It stated, inter alia:

‘He was a great friend of Boden, and shortly before the latter’s decease Mr Earnshaw presented him with the board and men which Boden had used in his private encounters with Paul Morphy.’

That article about Earnshaw by G.A. MacDonnell was reproduced on pages 192-194 of MacDonnell’s book The Knights and Kings of Chess (London, 1894).

9416. Photographic archives (3)

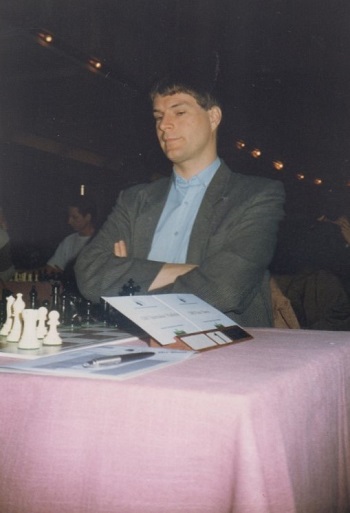

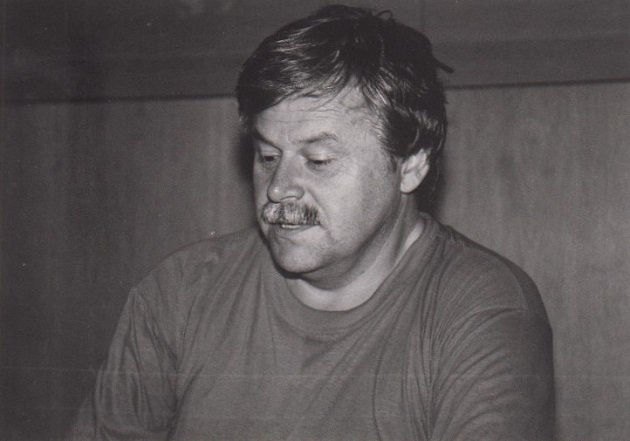

More photographs from our archive collection (referred to in C.N.s 9325 and 9363):

Lucas Brunner

Glenn Flear

Florin Gheorghiu

Vlastimil Hort

Josef Klinger

Joël Lautier

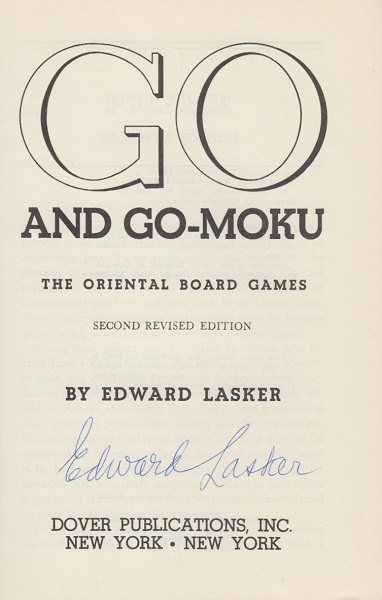

9417. Edward Lasker and Go

In 1934 Edward Lasker brought out a 214-page book Go and Go-Moku. A revised edition was issued by Dover in 1960, and below is the title page of our signed copy:

Lasker included a lengthy appendix on Go in the Philadelphia, 1945 edition of Modern Chess Strategy:

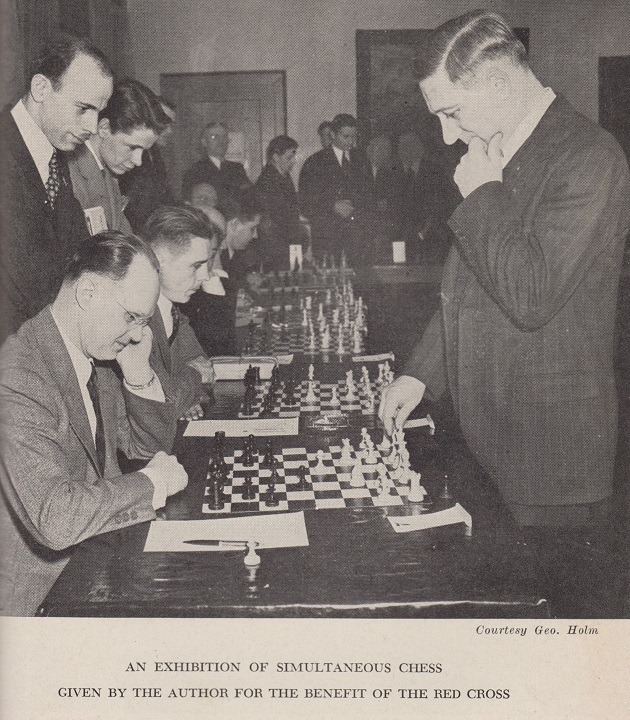

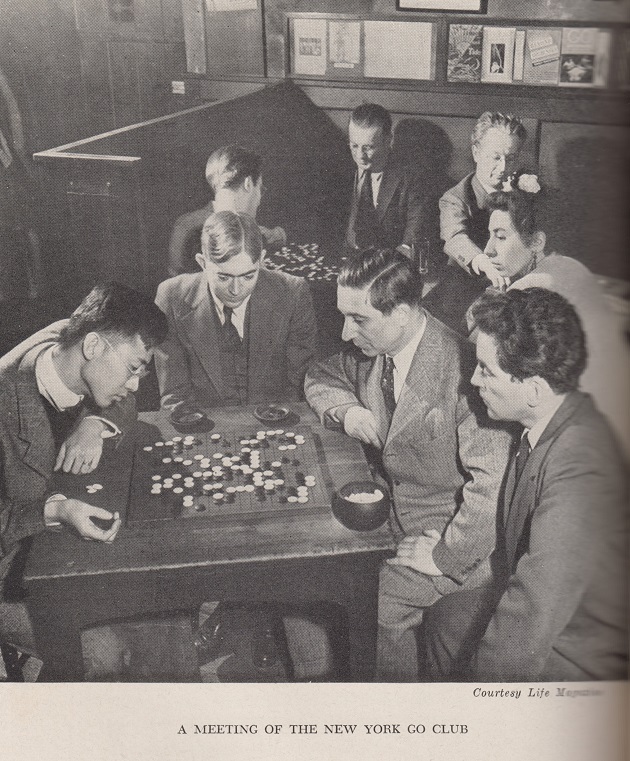

The book had two photographs, between pages 368 and 369:

When the 1945 edition of Modern Chess Strategy was reviewed on pages 112-113 of Chess World, 1 June 1946, C.J.S. Purdy praised the chess coverage but criticized the Go material:

‘We cannot understand how so logical a man could have added a 66-page appendix on the game of Go. The McKay Company will be wise to omit Go from the second edition, enabling them to lower the price.

We cannot discuss Go here, except insofar as Lasker compares it with chess. Following false “authorities”, he makes a colossal error in saying it is older than chess, “possibly three times as old”.

After mentioning Chinese legends setting the invention of wei-chi (go is only the modern Japanese name) as far back as 2000-odd BC, he goes on to say, more confidently:

“It is certain that in the tenth century BC, Wei-Chi was well known, for it is mentioned in a number of poems and allegories found in Chinese works dating from that period.”

The game mentioned is some other -chi, not wei. Chi means simply a board game. Lasker is about 20 centuries out.

H.J.R. Murray, the world authority on the histories of indoor games, wrote in a letter to us dated 15 January, “We now know that wei-chi, which the Chinese encyclopaedias date back to 2300 BC, was really only invented about 1000 AD.”

Later, Murray wrote to us:

“I haven’t Edward Lasker’s book, but from what you say I think he has used Korschelt’s articles on Go in the Mittheilungen der deutschen Gesellschaft für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens 1881, for I find the same story there. My impression is that references to the game’s antiquity are all taken from a fairly modern Japanese encyclopaedia and are no more reliable than what was said about the age of chess in similar European works. (There is some balderdash on this subject in the Encyclopaedia Britannica – Ed. Chess World.)

Chinese and Japanese claims for the antiquity of their games are all exaggerated, often by confusing similar names of dynasties or emperors and taking the earlier ones as the ones meant. Thus, when Lasker says that the first books devoted entirely to Wei-Chi were written during the T’ang dynasty (618-906 AD), he or his authorities have confused it with the Tang Dynasty (1000 AD) ...”

Lasker also calls go “unquestionably the greatest of all strategic games, including chess”. What are the criteria of greatness? Go is certainly the greatest in size, for it is played on a board of 361 points, each player having 181 counters. The object is to surround pockets of your opponent’s counters, so that the game develops into a number of separate engagements. As Lasker well says, go is more like modern war than chess is; it is ponderous, soulless.

Go will never appeal to as many diverse types of mentality as chess. Nor could it possibly inspire a literature of thousands of books, as chess has.’

9418. On-line research

From Patsy A. D’Eramo (North East, MD, USA):

‘As mentioned in Chess History Research Online, C.N. 7615 invited readers to suggest the best websites at which old chess magazines and newspaper columns can be consulted. One such subscription database is newspapers.com, and I have clipped some 12,000 chess columns and articles from that site. A rudimentary index of links to most of those articles appears on my personal website, D’Eramo Chess Project.’

9419. ‘Worthy of preservation’

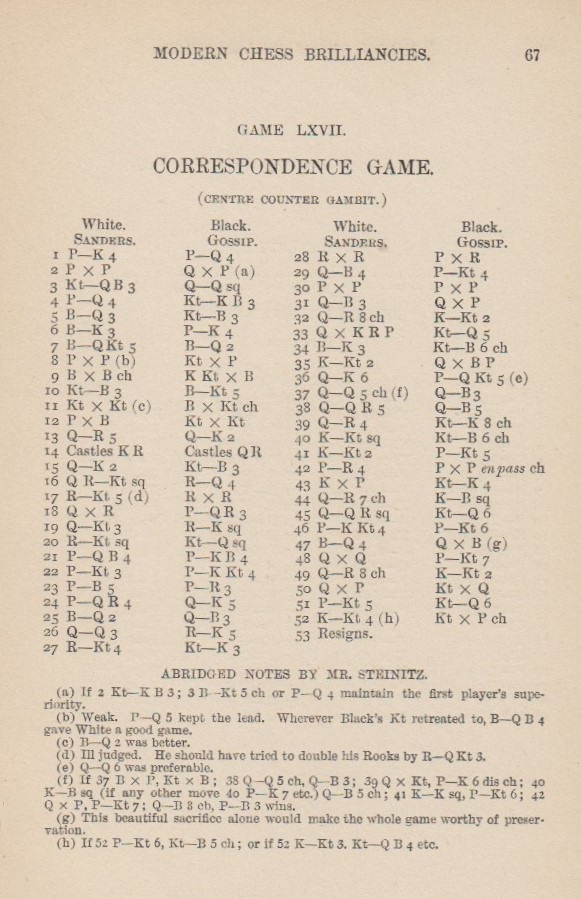

Page 67 of Modern Chess Brilliancies by G.H.D. Gossip (London, 1892):

Steinitz’s notes to the Sanders v Gossip game (‘in Mr Nash’s Correspondence Tourney’) were in the 3 May 1879 issue of The Field, page 519.

1 e4 d5 2 exd5 Qxd5 3 Nc3 Qd8 4 d4 Nf6 5 Bd3 Nc6 6 Be3 e5 7 Bb5 Bd7 8 dxe5 Nxe5 9 Bxd7+ Nfxd7 10 Nf3 Bb4 11 Nxe5 Bxc3+ 12 bxc3 Nxe5 13 Qh5 Qe7 14 O-O O-O-O 15 Qe2 Nc6 16 Rab1 Rd5 17 Rb5 Rxb5 18 Qxb5 a6 19 Qb3 Re8 20 Rb1 Nd8 21 c4

21...f5 22 g3 g5 23 c5 h6 24 a4 Qe4 25 Bd2 Qc6 26 Qd3 Re4 27 Rb4 Ne6 28 Rxe4 fxe4 29 Qc4 b5 30 axb5 axb5 31 Qc3 Qxc5 32 Qh8+ Kb7 33 Qxh6 Nd4 34 Be3 Nf3+ 35 Kg2 Qxc2 36 Qe6 b4 37 Qd5+ Qc6 38 Qa5 Qc4 39 Qa4 Ne1+ 40 Kg1 Nf3+ 41 Kg2 g4 42 h4 gxh3+ 43 Kxh3 Ne5 44 Qa7+ Kc8 45 Qa1 Nd3 46 g4 b3 47 Bd4

47...Qxd4 48 Qxd4 b2 49 Qh8+ Kb7 50 Qxb2+ Nxb2 51 g5 Nd3 52 Kg4 Nxf2+ 53 White resigns.

9420. Schlechter v Perlis

Position after 21...f6

White played 22 Rxb4 (Schlechter v Perlis, Carlsbad, 1911).

On page 39 of Chess Strategy and Tactics (New York, 1933) Fred Reinfeld and Irving Chernev wrote:

‘22 RxKt!?

A remarkable case of “chess blindness”: Schlechter is so concentrated on the logical result of his beautiful play from the 14th move on, that he completely overlooks the simple win of the exchange by 22 KtxPch. Strangely enough, Dr Tarrasch was the only annotator to point out this move.’

Such ‘only annotator’ claims are risky.

We have yet to find a complete set of notes by Tarrasch to the Schlechter v Perlis game, but he discussed the above position in ‘Über Schachblindheit (Amaurosis scachistica)’, in his book Die moderne Schachpartie. The article was reproduced in full in C.N. 8187.

It is true that shortly after the game was played a number of annotators praised 22 Rxb4. It received an exclamation mark in, for instance, the Deutsche Schachzeitung (September 1911, page 268) and the BCM (October 1911, page 395).

Spielmann’s notes to the game in the Münchner Neuesten Nachrichten were given on pages 402-403 of La Stratégie, November 1911, and the original German was reproduced on pages 116-118 of Schachjahrbuch für 1911 I. Teil by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1912). Here too 22 Rxb4 received an exclamation mark, but Spielmann later changed his mind, criticizing the move when annotating the game on pages 134-135 of his monograph Karl Schlechter (Stockholm, 1924):

‘22 Ta4xb4?

Ett av dessa psykologiskt intressanta fall av ömsesidig hypnos, eller som dr Tarrasch skämtsamt benämner det, “schackblindhet”. 22 Sxc6† hade varit att ge motståndaren nådestöten, medan nu partiet blott står att vinna genom ett subtilt tornslutspel.’

However, the claim by Reinfeld and Chernev about Tarrasch being the ‘only annotator’ is invalidated by the fact that the Wiener Schachzeitung (September-October 1911, page 316) criticized 22 Rxb4: ‘Ein Kuriosum; Schlechter übersieht, daß er mit 22 Se5xc6 viel rascher entscheiden konnte.’

On page 38 of part one of Vidmar’s Carlsbad, 1911 tournament book 22 Rxb4 received a question mark and a terse note: ‘Warum nicht Sc6†?’

9421. Seven Days in Bamberg

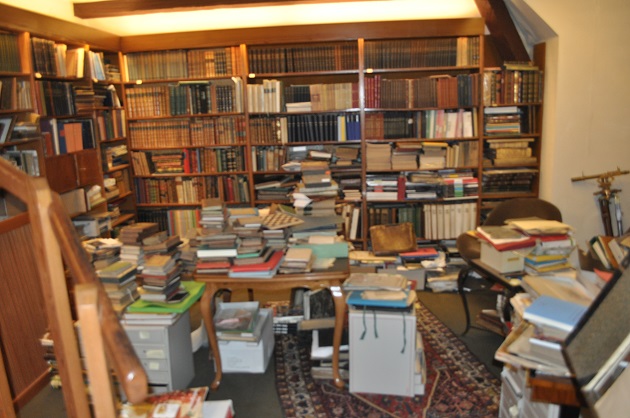

Just received from David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA): his latest book, Seven Days in Bamberg (Darien, 2015). It is a superbly produced 248-page hardback presenting highlights (colour photographs) from the chess collection, as yet unsold, of the late Lothar Schmid. The book’s price is $425, plus postage, and we shall be pleased to pass on to Mr DeLucia any messages from readers who wish to buy a copy.

Some photographs taken by him while visiting the collection in 2014 are shown here with his permission.

The main room of Lothar Schmid’s library

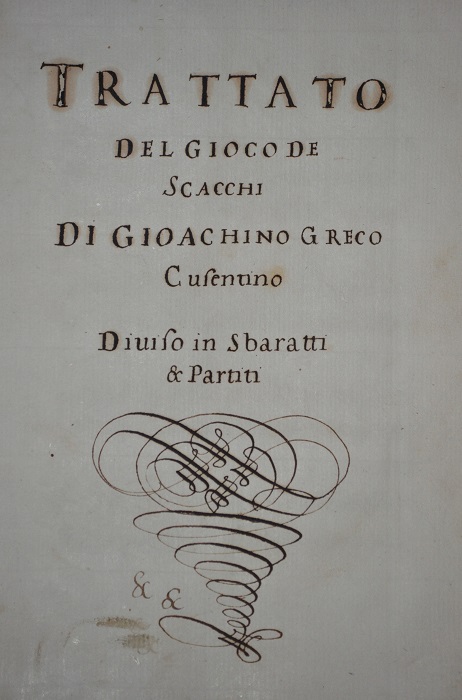

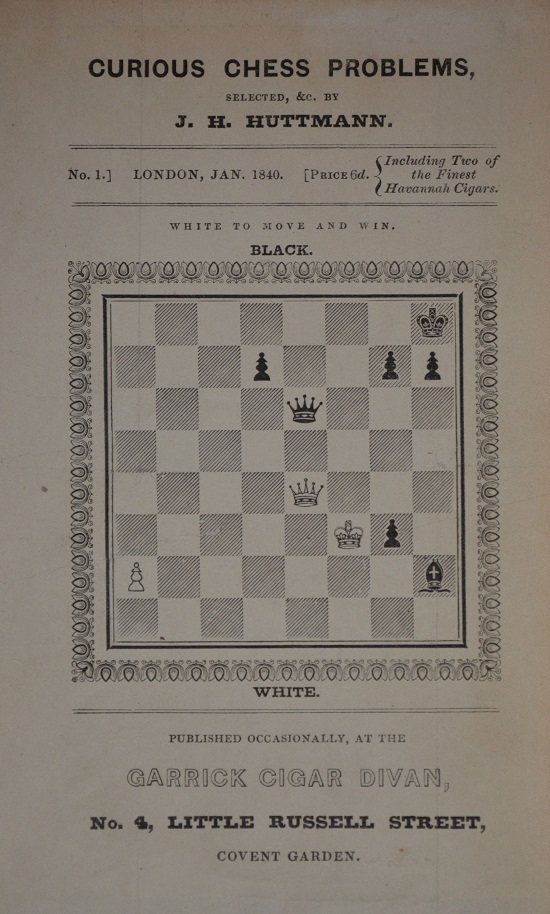

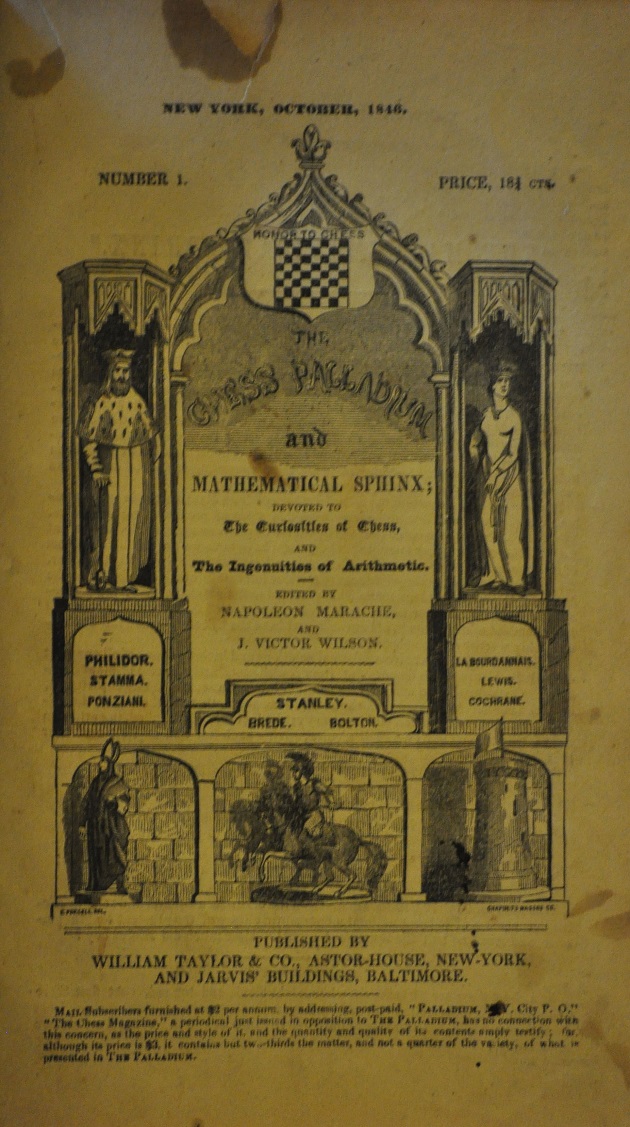

The three illustrations below show exceptionally rare items and come from, respectively, pages 54, 166 and 170 of Seven Days in Bamberg:

9422. Photograph collection

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘IMAGNO, an Austrian historical picture agency, has some of its records digitized online. Through a keyword search (“Schach”) the database reveals a number of fine photographs from the 1930s, featuring, among others, Alekhine, Bogoljubow, Capablanca, Euwe, Flohr, Koltanowski, Mieses, Sämisch and Spielmann.’

9423. Réti v Alekhine

Alekhine played 16...Bh3

Sean Robinson (Tacoma, WA, USA) writes regarding Réti v Alekhine, Baden-Baden, 1925:

‘How were the repetition rules applied at the time? Did a claim have to be made by one of the players, or could a referee/judge impose a decision without the players’ agreement?

If the tournament books (by Tarrasch and Grekov) and Réti’s annotations in La Prensa are accurate, version A of this game would seem to be illegal under modern rules, whereas versions B and C would both be legal, under a modern or a 1925 interpretation of the rules.

Whichever sequence is believed, it is important to remember that Alekhine’s repetition offer forced Réti’s hand, and Réti had the last word on whether to accept the draw. Alekhine’s annotations (and apparently Réti’s in La Prensa) support this point.

After 17...Bg4 (version B), Alekhine says this on page 11 of his second volume of best games (London, 1939):

“Giving the opponent the choice between three possibilities: (1) to exchange his beloved ‘fianchetto’ bishop; (2) to accept an immediate draw by repetition of moves (18 B-Kt2 B-R6 19 B-B3, etc.) which in such an early stage always means a moral defeat for the first player, and (3) to place the bishop on a worse square (R1). He finally decides to play ‘for the win’ and thus permits Black to start a most interesting counter-attack.”When Réti finally refused the draw with 20 Bh1 (again, in version B), Alekhine exclaimed, “At last!”

Alekhine annotated the phase after 17...Bg4 slightly differently in his book On the Road to the World Championship 1923-1927 (Oxford, 1984). From page 53:

“Now White is faced with an unpleasant choice. Obviously he cannot very well allow the exchange of bishops, because this would weaken his king’s position and grant the opponent equality at least, but to agree to a draw by an automatic repetition of moves would amount to an implicit admission that his novel treatment of the opening is by no means convincing. So there is nothing left but the modest retreat to h1, which is what he decides on in the end. This allows Black the gain of an important tempo, however.”

This is C.J. Feather’s translation of Alekhine’s text on pages 53-54 of Auf dem Wege zur Weltmeisterschaft (Berlin and Leipzig, 1932).

Euwe gave version B on pages 43-47 of Meet the Masters (London, 1940). After 19...Bg4 he introduced an idea which I have not seen elsewhere:

“And Alekhine claimed a draw by repetition of moves. Réti protested, and the tournament director ruled that the automatic draw by repetition had not yet come about.

The reporters wrote nothing about this; and some, in reproducing the game, omitted the repetition completely, publishing scores reading 16...B-R6 17 B-B3 B-Kt5; 18 B-R1. Yet the precise circumstances contribute useful evidence towards a correct judgment of the situation.

Réti now went 20 B-R1 and now Alekhine knew that, if he were to get a draw, he would have to fight for it.”

Examples of the omission of the repetition, as referred to by Euwe, are given in your article as version C: the 1925 Wiener Schachzeitung (Spielmann) and Deutsche Schachzeitung.

Both Réti and Alekhine were evidently aware of the repetition issue. Thus, the sporting question is not when Alekhine played ...h5, but when Réti played Bh1 and refused the draw.

In your feature article on repetition John Nunn referred to “world championship games from the early twentieth century” and wrote, “As I understand it, at one time the repetition rule required that the moves had to be repeated, rather than the positions”. The context of his point predates the Réti-Alekhine game, but it may be asked whether the same idea is relevant to the 1925 game.

It is unclear whether Réti and Alekhine had the same interpretation of the repetition rule. Although Réti was writing almost immediately after the game was played, it cannot be assumed that he, and not Alekhine, provided an accurate account of the move order.’

9424. Dutch photograph collection

Hans Mudde (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) notes that the Haagse Beeldbank website has many unknown photographs of, among others, Alekhine, Euwe and Botvinnik.

9425.

Nimzowitsch’s charm

A comment about Nimzowitsch on page 67 of Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929):

‘Once the strain of play is over, he is the most charming of men, always ready to give helpful advice or instruction to any serious student of the game.’

9426. Lasker

and Reshevsky (C.N. 9204)

Wanted: a better copy of the photograph below, which was published on page 4 of the Chicago Daily Tribune, 18 March 1921:

The newspaper’s caption was:

‘The youthful chess wizard, Samuel Rzeschewski, is seen here playing against Edward Lasker, western chess champion, seated opposite. Julius Rosenwald, the referee, is seated between them; Spectators from left to right are Alma Wells, who played the youthful prodigy at the Illinois Athletic club last Saturday night; Mrs Tachibana, cousin to the Emperor of Japan, Sophia Novakobsky, Mrs Julius Rosenwald, Mrs Jacob Rzeschewski, the boy’s mother, and, next to her, his father.’

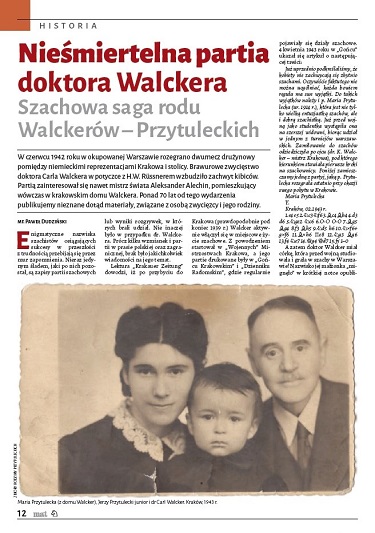

9427. Carl Walcker (C.N.s 7926, 7930, 8085 & 8265)

Paweł Dudziński (Ostrów Wielkopolski, Poland) has

forwarded us his article about Walcker on pages 12-15 of

the 4/2015 issue of mat.

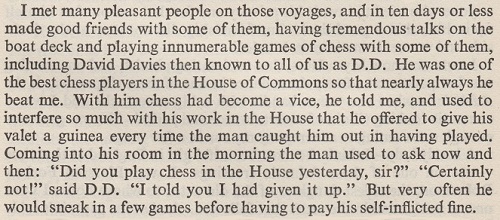

9428. Philip Gibbs and David Davies

Books by Philip Gibbs (1877-1962) have a few references to chess, including the passage shown below from page 286 of one of his autobiographical volumes, The Pageant of the Years (London, 1946). The section in question, ‘Crossing the Atlantic’ (pages 284-286), also related his meetings with Maxine (Blossom) Forbes-Robertson, John Galsworthy, Myra Hess, Ernest Shackleton and Clare Sheridan. It gave no dates, but on page 267 Gibbs mentioned that he crossed the Atlantic in 1919, 1920 and 1921.

As clarified on pages 359-360, David Davies (1880-1944) was later Lord Davies. Other references to his interest in chess will be appreciated.

9429. World championship contests

During the Interregnum, C.J.S. Purdy wrote an article entitled ‘The World Championship’ on page 100 of Chess World, 1 June 1946. After briefly referring to the London Rules and stating that with Alekhine’s death ‘the way is now clear for the FIDE to take complete control of the championship’, Purdy presented these proposals:

‘Match or Tournament?

Some advocate that the world title should be decided by tournaments.

After much thought, we disagree.

In the first place, a tournament proves nothing unless the winner’s margin is substantial; luck often plays a big part.

Further, the lifting of one tournament to overwhelming importance would reduce interest in other tournaments; before the War, big international tournaments were held frequently, and they aroused tremendous interest. Each big tournament was important in itself; it did not have to play second fiddle to anything. The proposed change would seriously jeopardize all that.

Nobody had any complaints against the match system except that matches were too infrequent and the champion more or less selected his challenger.

If matches are held at regular intervals of say 18 months or two years, and the challenger is selected by the FIDE on recent tournament results, there may still occasionally be faulty choices made, but there will undoubtedly be a vast improvement.

So the choice is between a revolutionary change which may be harmful, and an alteration which is certain to be beneficial.

Suitable conditions for a match would be: First to win four games, but by a margin of at least two points; provided that at least 12 games must be played, and not more than 24 games. After 24 games, the leader shall be champion. If scores equal, holder retains title.

In other words, do not let a one-point margin decide unless after a very protracted struggle neither player can do better. A 4-3 win after ten or 12 games would not be very satisfactory. On the other hand, if one player could build up a lead of four wins to two after 12 games it should be good enough. The strain of a 24-games match or longer should not be imposed unnecessarily. Labourdonnais and McDonnell killed themselves with long matches.

As to finance, we suggest a purse of 5,000 American dollars. Half the purse and expenses to be raised by the nation holding the match; the other half from a fund raised by the FIDE from subscriptions in all affiliated countries.

By all means hold a tournament to pick the first champion; after that, matches.’

9430. Nimzowitsch on the king’s role

From page 66 of Secrets of Chess Training by Mark Dvoretsky (London, 1991):

‘In the middlegame, the king is merely an extra, but in the endgame he is one of the star actors. Aron Nimzowitsch.’

This seems to be a relatively modern rendering of what appeared on page 81 of Nimzowitsch’s My System (London, 1929):

‘In the middle game the king is a mere “super”, in the end game on the other hand – one of the “principals”.’

This sentence, in the chapter entitled ‘The Elements of End-game Strategy’, is on page 66 of later editions of My System produced by the same publisher, G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., and on page 92 of the version edited by Fred Reinfeld (Philadelphia, 1947).

Two other translations:

Source: page 57 of the Hays Publishing, Inc. edition of My System (Dallas, 1991).‘In the middlegame the king is a mere “observer”, in the endgame on the other hand – one of the “principals”.’

‘In the middlegame, the king is a mere extra, but in the endgame it is one of the principal actors.’

Source, page 109 of the Quality Chess edition of My System (Göteborg, 2007).

Nimzowitsch’s text on page 114 of Mein System (Berlin, 1925) was:

‘Im Mittelspiel ist der König bloßer Statist, im Endspiel dagegen – einer der Hauptakteure.’

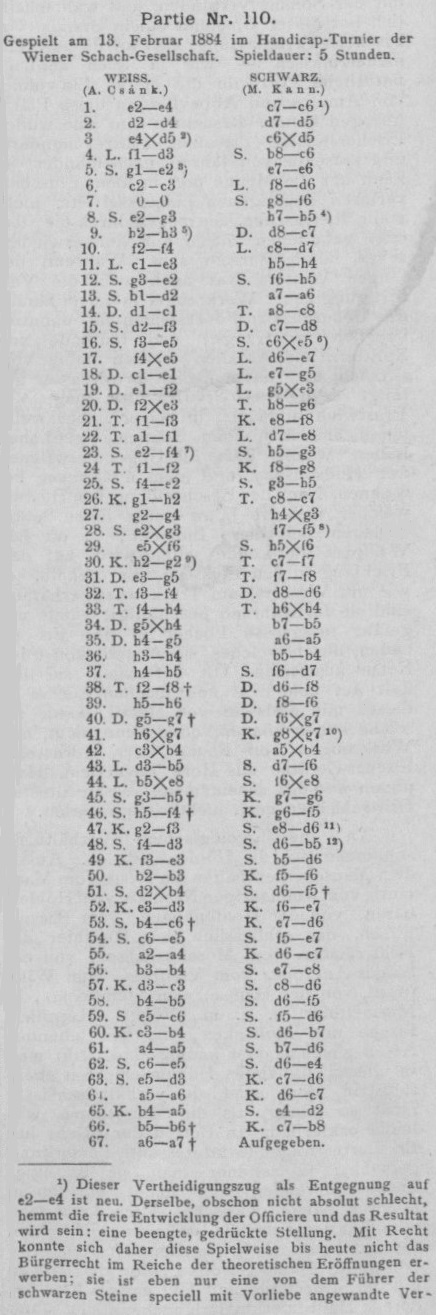

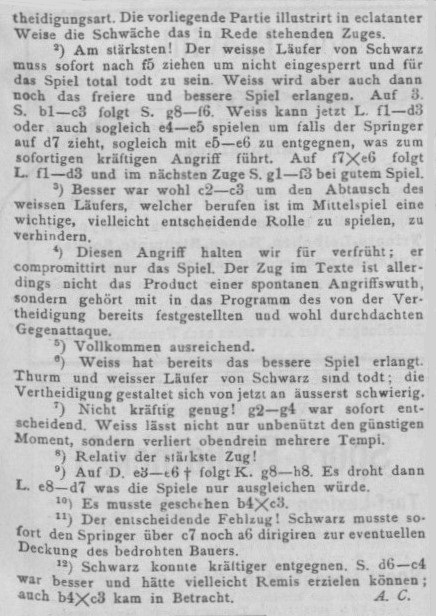

9431. The Caro-Kann Defence

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) has found an earlier specimen of 1...c6 played by M. Kann, on pages 698 and 699 of Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung, 7 August 1884 (A. Csánk v M. Kann, Vienna, 13 February 1884):

1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 exd5 cxd5 4 Bd3 Nc6 5 Ne2 e6 6 c3 Bd6 7 O-O Nf6 8 Ng3 h5 9 h3 Qc7 10 f4 Bd7 11 Be3 h4 12 Ne2 Nh5 13 Nd2 a6 14 Qc1 Rc8 15 Nf3 Qd8 16 Ne5 Nxe5 17 fxe5 Be7 18 Qe1 Bg5 19 Qf2 Bxe3 20 Qxe3 Rh6 21 Rf3 Kf8 22 Raf1 Be8 23 Nf4 Ng3 24 R1f2 Kg8 25 Ne2 Nh5 26 Kh2 Rc7 27 g4 hxg3+ 28 Nxg3 f5 29 exf6 Nxf6 30 Kg2 Rf7 31 Qg5 Rf8 32 Rf4 Qd6 33 Rh4 Rxh4 34 Qxh4 b5 35 Qg5 a5 36 h4 b4 37 h5 Nd7 38 Rxf8+ Qxf8 39 h6 Qf6 40 Qxg7+ Qxg7 41 hxg7 Kxg7 42 cxb4 axb4 43 Bb5 Nf6 44 Bxe8 Nxe8 45 Nh5+ Kg6 46 Nf4+ Kf5 47 Kf3 Nd6 48 Nd3 Nb5 49 Ke3 Nd6 50 b3 Kf6 51 Nxb4 Nf5+ 52 Kd3 Ke7 53 Nc6+ Kd6 54 Ne5 Ne7 55 a4 Kc7 56 b4 Nc8 57 Kc3 Nd6 58 b5 Nf5 59 Nc6 Nd6 60 Kb4 Nb7 61 a5 Nd6 62 Ne5 Ne4 63 Nd3 Kd6 64 a6 Kc7 65 Ka5 Nd2 66 b6+ Kb8 67 a7+ Resigns.

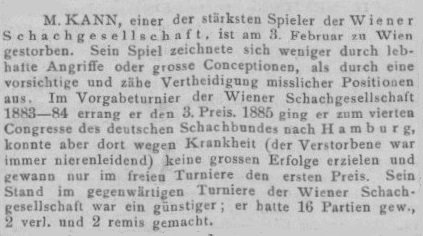

Our correspondent adds that Kann’s death was reported on page 118 of the 12 February 1886 edition of Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung:

9432. Alekhine

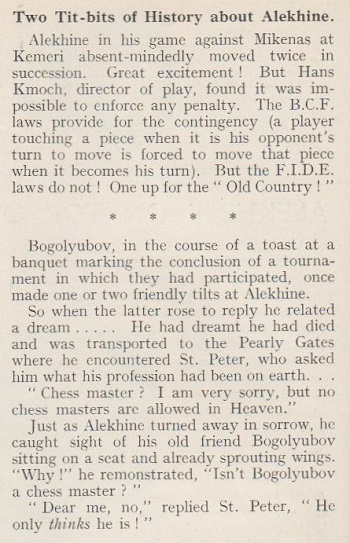

The extract below from page 114 of CHESS, 14 December 1937 is relevant to our items ‘Two moves in succession’ (C.N.s 3202 and 5181) and ‘Heaven’ (C.N.s 5600, 6813 and 8672):

9433. Another set of chess photographs

Thomas Höpfl (Halle, Germany) notes that the Chess in Luxembourg webpage has some fine photographs, including shots of Boris Spassky.

9434. Capablanca book by Miguel A. Sánchez

A book just received, José Raúl Capablanca. A Chess Biography by Miguel A. Sánchez (Jefferson, 2015), provides a dramatic illustration of how chess scholarship has developed, in some fields, since the 1970s. The author’s two-volume work Capablanca, leyenda y realidad (Havana, 1978) has been expanded and improved beyond all recognition.

9435. Chess in Singapore (C.N.s 7755 & 7766)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

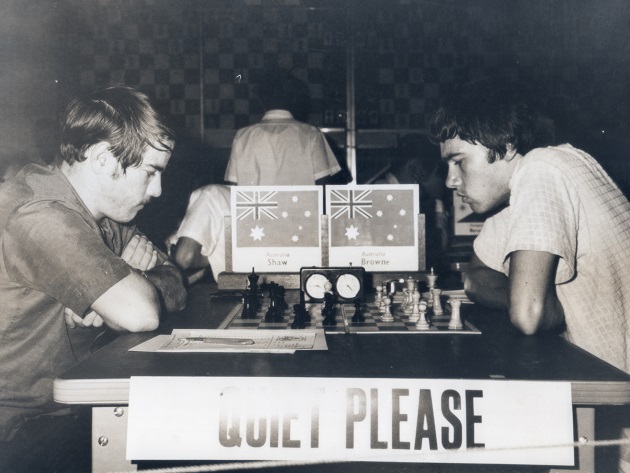

‘Further research on chess in old Singapore has unearthed parts of Lim Kok Ann’s private collection of original photographs of local chess in the 1950s and 1970s. A large number of pictures will be available in a book on Singapore chess planned for release later in 2015 by the World Scientific Publishing Company. Some foreign players are featured too, e.g. Walter Browne in play against Terry Shaw in the FIDE Zone 10 championship held in Singapore on 4-21 August 1969.’

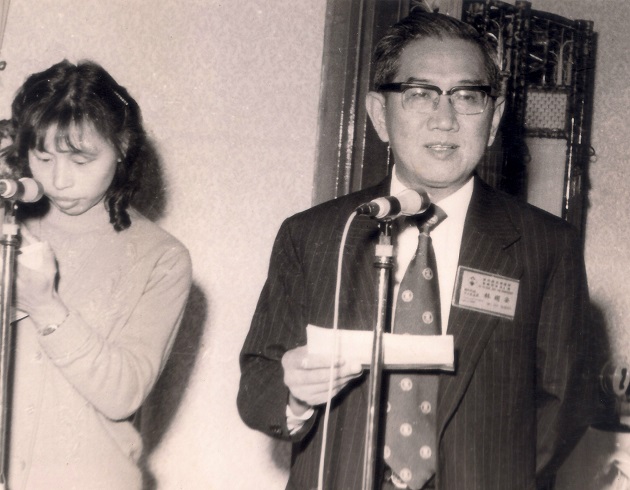

Our correspondent has also forwarded a photograph of Lim Kok Ann giving a speech in the early 1970s:

9436. Mental decline

A.’s opinion that indoor games may abate mental decline becomes B.’s claim that chess prevents Alzheimer’s disease. As chronicled in a series of articles by Jonathan Bryant, this field is remarkable for its lack of intellectual rigour.

9437. Nineteenth-century British players (C.N.s 8705 & 8817)

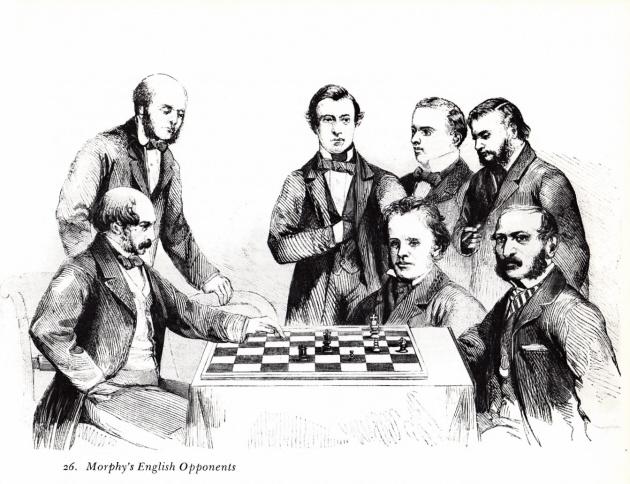

Concerning this picture from page 105 of Paul Morphy The Pride and Sorrow of Chess by David Lawson (New York, 1976), in C.N. 8817 Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) offered, very tentatively, the following caption (from left to right): T.W. Barnes, G. Walker, S.S. Boden, A. Mongrédien, H.E. Bird, R.W. Wormald and J.J. Löwenthal.

Can any reader take the matter forward? For example, where was the illustration published before 1976 and, particularly, in the nineteenth century?

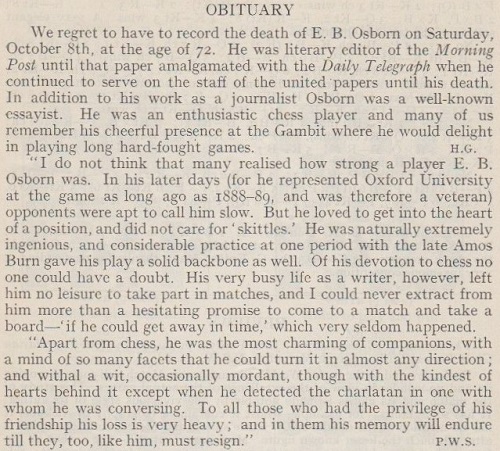

9438. E.B. Osborn (C.N.s 4189 & 5570)

E.B. Osborn’s review of A History of Chess by H.J.R. Murray on pages 1 and 2 of the Times Literary Supplement, 23 October 1913 exemplifies how new books were often scrutinized in a long lost age.

From page 500 of the November 1938 BCM (contributions by Golombek and Sergeant):

The obituary of Osborn (‘Journalist, critic, and writer of verse’) on page 16 of The Times, 11 October 1938 included the following:

‘He wrote, too, on chess, which was among his favourite recreations, and until recent years he could often be seen at the chess congresses or absorbed in a quiet game with some great masters in a London café.’

Osborn’s participation in a match (Hackney, 18 March 1891) between the Oxford University Chess Club (he represented Magdalen College) and the North London Chess Club was mentioned on page 99 of the April 1891 International Chess Magazine. His game, a victory over F. Wallis, was published on page 3 of the London Daily News, 19 March 1891:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 Qf6 5 Be3 Bc5 6 c3 Nge7 7 Bb5 O-O 8 O-O Bb6 9 f4 Nxd4 10 cxd4 d6 11 Nc3 c6 12 Be2 Ng6 13 Kh1 Qd8 14 f5 Ne7 15 Bd3 f6 16 Rf3 d5 17 Rh3 dxe4 18 Bc4+ Nd5 19 Qh5 h6

20 Bxh6 Qe8 21 Qg4 Rf7 22 Nxd5 cxd5 23 Bxd5 (‘PxP’), ‘and White won’.

The game was also given in the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 21 March 1891, page 405.

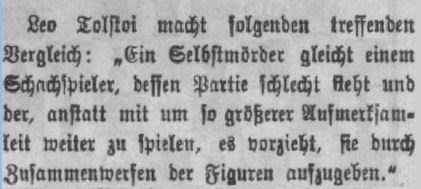

9439. Tolstoy and chess

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) writes:

‘On page 277 of the 28 August (old style) 1904 issue of Düna Zeitung Carl Behting’s chess column (with contributions by Friedrich Amelung) has a quote by Leo Tolstoy which was unknown to me:

“Leo Tolstoi macht folgenden treffenden Vergleich: ‘Ein Selbstmörder gleicht einem Schachspieler, dessen Partie schlecht sieht und der, anstatt mit um so größerer Aufmerksamkeit weiter zu spielen, es vorzieht, sie durch Zusammenwerfen der Figuren aufzugeben.’”’

Mr Sánchez has also provided files featuring two games mentioned in Tolstoy and Chess: Sergei Tolstoy v Behting on page 326 of the Düna Zeitung, 14 October (old style) 1900 issue, and Leo Tolstoy v Maude on page 423 of the Rigasche Zeitung, 31 December (old style) 1910 issue.

9440. Books about leading modern chessplayers

The list of books on Viswanathan Anand, Levon Aronian, Magnus Carlsen, Fabiano Caruana, Boris Gelfand, Vassily Ivanchuk, Vladimir Kramnik and Veselin Topalov continues to expand, some additions having been made of late courtesy of Yakov Zusmanovich (Pleasanton, CA, USA). Information about further titles is always welcome.

From our collection:

Magnus Carlsen

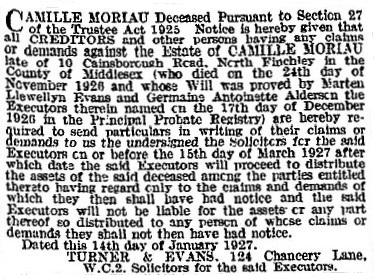

9441. Moreau, Moriau, etc.

As shown on pages 354-355 of A Chess Omnibus and in C.N. 4574, many gaps and much confusion exist regarding Colonel [Charles?] Moreau and C[amille] Moriau.

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) informs us that he first saw Moriau’s forename given as Camille in a chess article in the Australasian, 16 April 1892. He has now found Moriau’s exact date of death (24 November 1926), on page 4 of The Times, 14 January 1927:

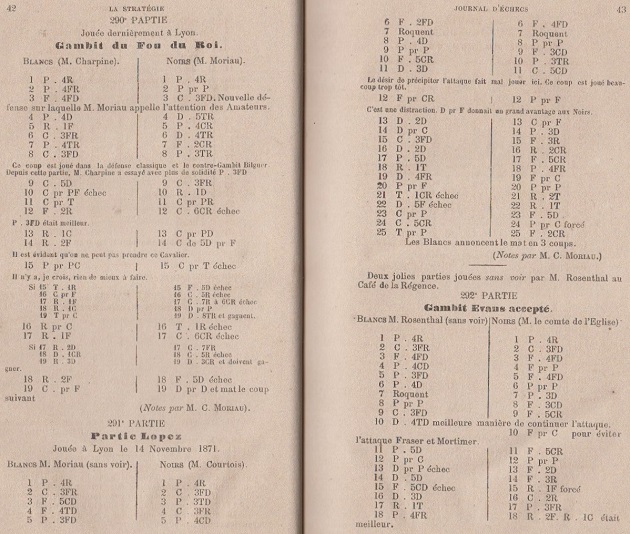

In C.N. 2482 a correspondent referred to an article by C. Moriau about 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 Nc6 on pages 44-48 of the February 1874 Deutsche Schachzeitung, and we add here that a game with that opening was one of two annotated by Moriau on pages 42-43 of La Stratégie, 15 February 1872:

Charpine v Moriau: 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 Nc6 4 d4 Qh4+ 5 Kf1 g5 6 Nf3 Qh5 7 h4 Bg7 8 Nc3 h6 9 Nd5 Nf6 10 Nxc7+ Kd8 11 Nxa8 Nxe4 12 Be2 Ng3+ 13 Kg1 Nxd4 14 Kf2 Ndxe2 15 hxg5 Nxh1+ 16 Kxe2 Re8+ 17 Kf1 Ng3+ 18 Kf2 Bd4+ 19 Nxd4 Qxd1 ‘and mate next move’.

Moriau (blindfold) v Courtois: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 c3 b5 6 Bc2 Bc5 7 O-O O-O 8 d4 exd4 9 cxd4 Bb6 10 Bg5 h6 11 Qd3 Nb4 12 Bxf6 gxf6 13 Qd2 Nxc2 14 Qxc2 d6 15 Nc3 Be6 16 Qd2 Kg7 17 d5 Bg4 18 Kh1 f5 19 Qf4 Bxf3 20 gxf3 fxe4 21 Rg1+ Kh7 22 Qf5+ Kh8 23 Nxe4 Bd4 24 Ng5 hxg5 25 Rxg5 Bg7. ‘White announced mate in three moves.’

The games were introduced as follows on page 41:

‘... nous recevons de Lyon les deux parties suivantes, qui nous dévoilent un jeune Amateur, M. C. Moriau, doué de remarquables dispositions et certainement appelé à prendre, dans peu, une place honorable parmi les plus forts joueurs.’

Pages 146-147 of the May 1873 Deutsche Schachzeitung had a victory by C. Moriau over L. Bertrand (Lyons, 26 January 1873), whereas on pages 199-202 of La Stratégie, 15 July 1873 Léon Bertrand contributed an article in verse on a game lost by him to ‘Moriaud’. A further complication is that the 1875 volume of La Stratégie has a number of games by a player named Camille Morel. Finally, as regards the C.A. Moreau or C.L. Moreau mentioned in 1930s US sources (C.N. 4574) an addition is given below from page 270 of the December 1937 Chess Review:

9442. Berliner Tageblatt

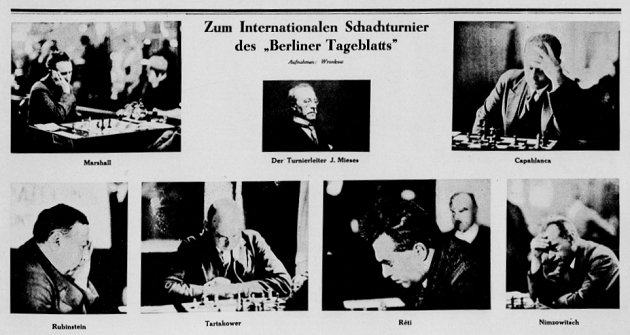

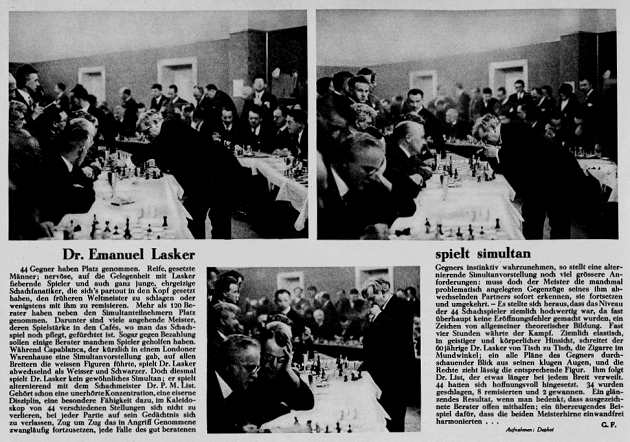

From Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic):

Berliner Tageblatt, 28 October 1928, page 3

Berliner Tageblatt, 12 May 1929, page 2

9443.

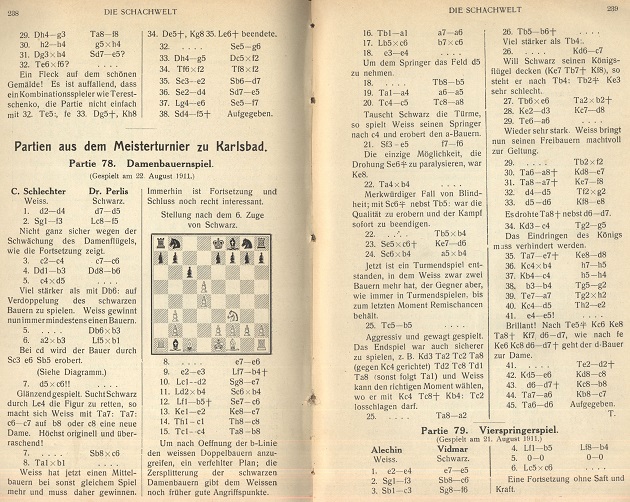

Schlechter v Perlis (C.N. 9420)

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) points out that

Tarrasch annotated the full Schlechter v Perlis game on

pages 238-239 of Die Schachwelt, 12 September 1911

and stated that at move 22 White should have played Nxc6+

instead of Rxb4.

C.N. 9420 mentioned that the September-October 1911 Wiener Schachzeitung also criticized 22 Rxb4, but, as Mr Anderberg notes, page 267 of that issue indicated that it was not published until December.

9444. A tribute to Anderssen by Steinitz

Steinitz is often portrayed as crabby, cranky and crusty, yet much of his literary output was generous and good-natured. When Adolf Anderssen died, Steinitz wrote a lengthy tribute on page 362 of The Field, 29 March 1879, and some extracts are presented below:

‘By the death of Professor Anderssen, which was briefly announced in our last number, the chess world has lost one of the greatest masters of all times; and perhaps only very few will be disposed to deny that in some respects he might be called the greatest player of our era, without injustice to his chief rivals. For the test of general tournaments has comparatively recently been added to the proof of strength in set matches, and no living player can boast of such a grand record of numerous triumphant victories in tournaments as have been achieved by Anderssen. Nor had he his peer as regards elegance and brilliancy of style; and some of his games, like those published below [the Immortal Game and the Evergreen Game], will ever be regarded as amongst the finest specimens of bold and surprising chess tactics, combining beauty of conception with depth of design.’

‘His style of play at the time [London, 1851] showed a clear supremacy over his predecessors and contemporaries, and it was generally admitted that his hard-earned victory was well deserved. After this great triumph he was for years considered facile princeps amongst the chess masters of the age. But he had no opportunities for the exercise of his chess genius, and he solely devoted himself to his professional duties up to 1858 ... Thus it happened that he was completely out of practice when in 1858 he paid a visit to Paris, at his own expense, to play a friendly match with the young American Morphy, whose precocity at an early age stands unexampled in the annals of chess, and who had then already defeated such masters as Löwenthal and Harrwitz. Anderssen actually fared worse, for he only scored two games and two draws against the great American’s seven; and though Morphy was undoubtedly the stronger at that time, the intrinsic value of the games shows that it would be unfair to make that score the absolute test of their relative force. For Morphy’s excellent chess career was cut short by his retirement after that event, while Anderssen stood successfully before the public for 20 years longer in numerous contests, and there is no living active player whom he has not defeated at some time or other, though some have scored the majority against him in the personal encounters. Never again did he commit the great mistake of allowing his strength to get rusty for years, and he kept his genius in working order by seeking constant practice amongst his own pupils.’

‘[Steinitz, who referred to himself in the third person] had so much improved that a match was proposed between him and Anderssen, which ultimately came off in July and August 1866, and ended in a victory for Steinitz by eight games to six. Anderssen, however, took his revanche at the Baden International Tournament of 1870, where he headed Steinitz by half a game in the score, thus coming out for the third time in succession as chief winner in international contests on a grand scale, and under different conditions of play.’

‘As far as chess tournaments are concerned, Anderssen’s record stands, therefore, unparalleled and unapproached; and before a decision can be arrived at amongst the candidates for the chief chess honours of the age, it remains to be seen whether the tournament or the match test will prove itself in course of time the best criterion of strength.’

‘In his private character, Anderssen was honest and honourable to the core. Without fear or favour, he straightforwardly gave his opinion, and his sincere disinterestedness became so patent in the course of his career that his word alone was mostly sufficient to quell such chess disputes as have sometimes arisen in tournaments, for he had often given his decision in favour of a rival who was likely to beat him in the final score.’

Steinitz’s notes to the Immortal Game included the following after 18 Bd6:

‘This and the rest of Anderssen’s conduct of the attack mark the limit of ingenuity and brilliancy exhibited in the actual contest up to our time.’

His concluding observation on that Anderssen v Kieseritzky game:

‘In memoriam of Anderssen, the present masterpiece will be treasured as an example of chess genius as long as the game shall be played.’

The annotations by Steinitz to the other game were shown in C.N. 6420; see our new feature article: Anderssen v Dufresne: The Evergreen Game.

9445. Match record

From page 57 of The Kings of Chess by William Hartston (London, 1985):

‘Steinitz defeated Dubois [in 1862], to begin the most impressive match record in the history of chess.’

9446. Another Fischer game

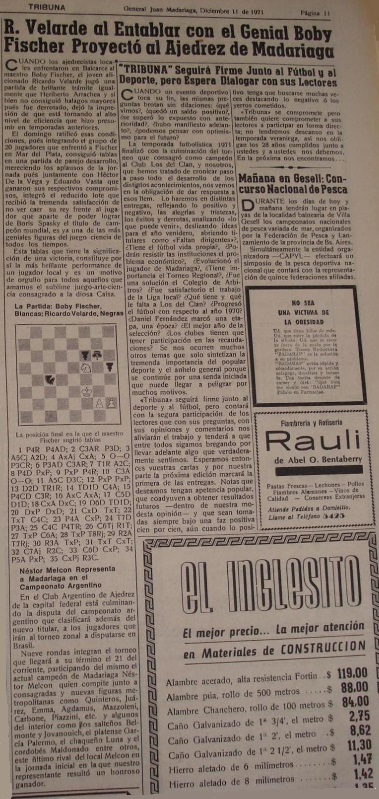

Carlos Drake (Buenos Aires) forwards a chess report on page 11 of Tribuna, 11 December 1971:

Robert James Fischer – Ricardo L. Velarde

Simultaneous exhibition, Mar del Plata, 5 December 1971

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 Bb5+ Bd7 4 Bxd7+ Nxd7 5 O-O g6 6 c3 Ngf6 7 Re1 Bg7 8 d4 cxd4 9 cxd4 e5 10 Nc3 O-O 11 Bg5 Qb6 12 dxe5 dxe5 13 Qd2 Rfe8 14 Rad1 Nc5

15 b4 Ne6 16 Bxf6 Bxf6 17 Nd5 Qd8 18 Nxf6+ Qxf6 19 Qd6 Rad8 20 Qxe5 Qxe5 21 Nxe5 Rxd1 22 Rxd1 Ng5 23 f4 Nxe4 24 Rd7 f6 25 Ng4 h5 26 Nh6+ Kh8 27 Rxb7 Nc3 28 Rxa7 Re1+ 29 Kf2 Re2+ 30 Kf3 Rxa2 31 Rxa2 Nxa2 32 Nf7+ Kg7 33 Nd6 Nxb4 34 f5 gxf5 35 Nxf5+ Kg6 Drawn.

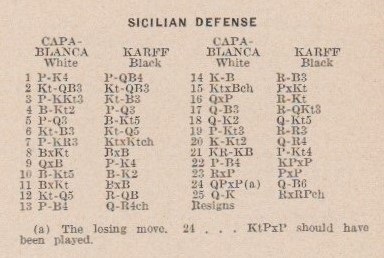

9447. Capablanca v Karff

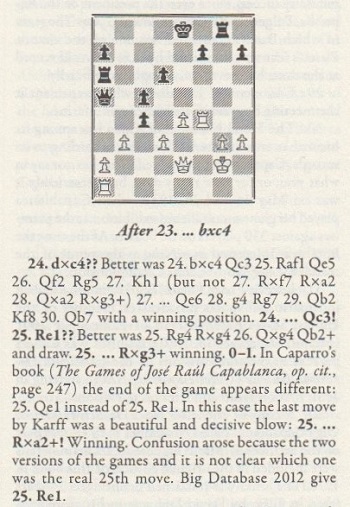

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) writes:

‘A copy of Miguel A. Sánchez’s José Raúl Capablanca. A Chess Biography (C.N. 9434) has just reached me. Having an interest in the career of Mona May Karff, I was immediately struck by the sub-standard treatment of Capablanca’s loss to her in a simultaneous exhibition (+19 –2 =1) at the Marshall Chess Club, New York on 6 November 1941. Although Sánchez referred to Karff on page 471 as a “former United States Women’s Chess Champion and the strongest female player in the country”, the endnote on pages 533-534 has, in addition to a speculative attempt to drag in medical points, a statement by Sánchez that it was “an unexpected defeat”.

After 16 Qxf6 Sánchez wrote that “White has a winning position”, whereas Karff had some compensation for the pawn because her queen and rooks were more actively placed, but what is most disheartening is Sánchez’s discussion of how the game ended: he gave the conclusion as 25 Re1 Rxg3+, making no mention of the more natural and stronger continuation 25…Qxg3+ 26 Kh1 Rxa2. Moreover, he claimed that it was unclear whether Capablanca’s 25th move was 25 Re1 or 25 Qe1:

It is inexplicable why Sánchez referred merely to the Caparrós book and a database, ignoring the obvious primary source, the American Chess Bulletin. Page 99 of the September/October 1941 issue gave the game-score, and I see no reason to doubt that the finish was as recorded by the Bulletin, i.e. 25 Qe1 Rxa2+:

1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 g3 Nf6 4 Bg2 d6 5 d3 Bg4 6 Nf3 Nd4 7 h3 Nxf3+ 8 Bxf3 Bxf3 9 Qxf3 e5 10 Bg5 Be7 11 Bxf6 Bxf6 12 Nd5 Rc8 13 c4 Qa5+ 14 Kf1 Rc6 15 Nxf6+ gxf6 16 Qxf6 Rg8 17 Qf3 Rb6 18 Qe2 Qb4 19 b3 Ra6 20 Kg2 Qa5 21 Rhf1 b5 22 f4 exf4 23 Rxf4 bxc4 24 dxc4 Qc3

25 Qe1 Rxa2+ 26 White resigns.

Sánchez’s endnote 33 is very poorly written: “… after having reached material and positional advantage”, “Starting in Buenos Aires, 1927, the frequency ...”, “and draw”, “Caparro’s”, “... the end of the game appears different”, “Confusion arose because the two versions of the games and it is not clear which one was the real 25th move …”, and “Big Database 2012 give”.

Incidentally, if Sánchez had consulted the American Chess Bulletin he could have quoted this snippet about the game:

“To Miss Karff, first to turn in the report of a victory, was awarded a copy of Capablanca’s Chess Primer, autographed by the author. Louis J. Wolff, captain of the Columbia varsity team of which the Cuban was a member, paid a finely phrased tribute to Capablanca in introducing him to the large audience. There was a bit of sardonic humor, he remarked, in the thought that a player winning from the master should receive a primer.”’

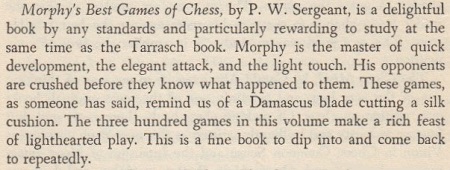

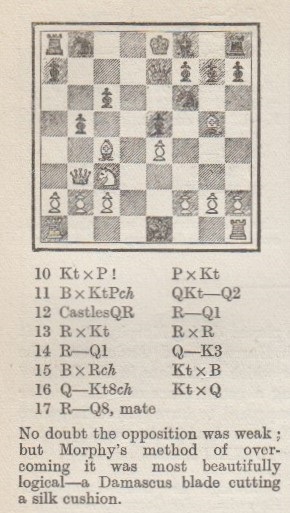

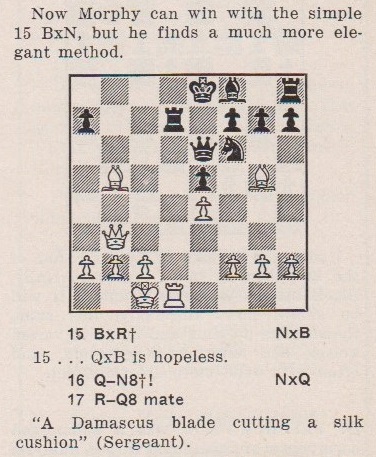

9448. A Damascus blade cutting a silk cushion

A few jottings on a colourful old phrase.

From page 181 of How To Get More Out Of Chess by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1957):

(There was no ‘Best’ in the title of Sergeant’s book, as Reinfeld should have known, given that, also in 1957, he contributed an Introduction to a new Dover edition.)

The ‘someone’ who made the Damascus blade remark was Sergeant himself, at the end of Game LXXIX (Morphy v the Duke and Count) in Morphy’s Games of Chess (pages 149-150):

That Reinfeld was aware of this is shown by the conclusion of his article about the game on page 45 of the February 1956 Chess Review:

9449. Walter Penn Shipley Scrapbooks

John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) points out a collection of chess photographs on the website of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

9450. Koltys Coments

The above heading is from page 2 of the Chess Digest Magazine, March 1969. The article by Koltanowski included, on the next page, this item:

Passing over the foreseeably wretched prose, we note the following with regard to Koltanowski’s assertions about himself:

- ‘... playing Tylor for the first time’. They had played earlier, at Ramsgate in April 1929;

- The quoted game against Tylor, played in the Premier Reserves tournament at Hastings, 1929-30, began 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 d6 3 Nc3 Nbd7 4 e4 e5 5 Bc4 Be7 6 O-O O-O 7 Qe2 exd4 8 Nxd4 Re8 9 Bxf7+ (Chess Amateur, February 1930, pages 106-107);

- Koltanowski’s game against Alekhine at London, 1932 was a Ruy López (given in Alekhine’s second Best Games volume);

- ‘... I still won the premier reserve’: Koltanowski and Tylor shared first place (BCM, February 1930, page 50);

- ‘... had my revenge a number of times’ against Tylor. On page 147 of his book With the Chess Masters (San Francisco, 1972) Koltanowski listed his individual record against Tylor as +2 –1 =2. He called him ‘Taylor’.

9451. Sacrifice or blunder?

From page 54 of Chess Marches On! by Reuben Fine (New York, 1945):

Elsewhere (e.g. on page 73 of CHESS, December 1972) the observation has been quoted as a remark by George Koltanowski to Sir George Thomas.

An editorial note (by B.H. Wood) appeared at the end of an article by Koltanowski on pages 180-181 of the 14 January 1936 issue of CHESS:

On page 87 of With the Chess Masters (San Francisco, 1972) Koltanowski named E.S. Tinsley as his interlocutor and referred to his queen, and not the exchange:

The following page showed the game (Koltanowski v E.G. Sergeant, Hastings, 31 December 1928), which reached this position after Black’s 19th move:

No notes were supplied, but Koltanowski punctuated his next move, Qxc5, with ‘?!’. The game was also published, storyless, on pages 83-84 of his book Chessnicdotes 1 (Coraopolis, 1978) with notes from The Field (and one analytical addition by Koltanowski towards the end of the game).

On page 54 of the second volume of Chessnicdotes (Coraopolis, 1981) it was back to Sir George Thomas and the ‘exchange’ version from CHESS in 1936:

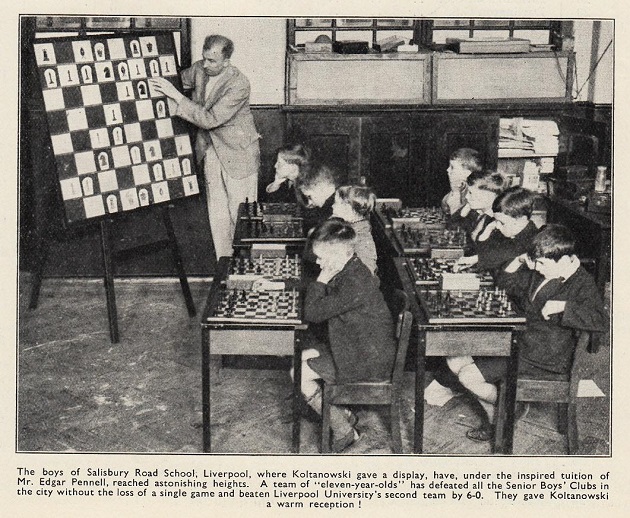

9452. Edgar Pennell

Copying usually goes hand-in-hand with incompetence.

This photograph of Edgar Pennell from page 275 of CHESS, 14 April 1937 was included in C.N. 8894 (see too The Chess Skewer).

In July 2015 our scan (which has ‘Pennell’ in the file name) was lifted for use on the website Chess & Strategy (Philippe Dornbusch) as a quiz question. The CHESS caption was not only deleted but also misunderstood, since the French site imagined that the man at the demonstration board was Koltanowski. It reported that over 700 readers had identified him.

Mr Dornbusch’s page brazenly concludes:

‘© Chess & Strategy - Reproduction et diffusion interdites.’

9453. Capablanca’s high blood pressure

From Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand):

‘The information about Capablanca’s high blood pressure in chapters 17 and 18 and Appendix II of Miguel Sánchez’s new biography provides an opportunity to reconsider the view that his fatal stroke was caused by stress.

Capablanca’s Death shows a letter dated 6 November 1942 from Dr A. Schwartzer to Olga Capablanca, and she is quoted as follows in The Genius and the Princess:

“Unfortunately I had no control over things outside our house. Certain aggravations caused to Capa in the last few months of his life precipitated his end. He spoke of this himself, and such was the opinion of his physicians, as both of them have written to me.”

“The most menacing was the part dealing with aggravations, for at the time he was confronted with some nasty ones in connection with his divorce. He faced up to some unfair demands and actions.”

Page 301 of your book on Capablanca refers to his participation in the 1938 AVRO tournament:

“Olga Capablanca recalls that his high blood pressure nearly cost him his life. ‘A doctor screamed at me, “How could you let him play?”’”

Capablanca had a family history of hypertension, and medical understanding of the condition has advanced since the 1940s. Below, for example, is a comment from the American Heart Association:

“Although stress is not a confirmed risk factor for either high blood pressure or heart disease, and has not been proven to cause heart disease, scientists continue to study how stress relates to our health. And while blood pressure may increase temporarily when you’re stressed, stress has not been proven to cause chronic high blood pressure.”’

9454. ForteanTimes

Pages 50-52 of the September 2015 issue of ForteanTimes contain, as Alan O’Brien (Mitcham, England) has informed us, an article by S.D. Tucker entitled ‘A Pawn in the Game’. It quotes many of the FIDE President’s statements, with due credit to Kirsan Ilyumzhinov and Aliens.

| First column | << previous | Archives [133] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.