Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [79] | next >> | Current column |

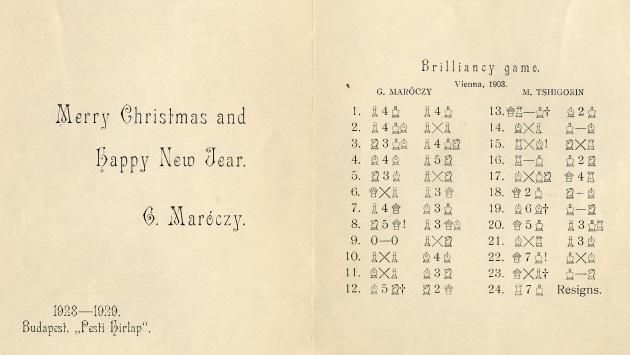

6928. Christmas greeting card (C.N. 6922)

David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA) sends a copy of Maróczy’s card:

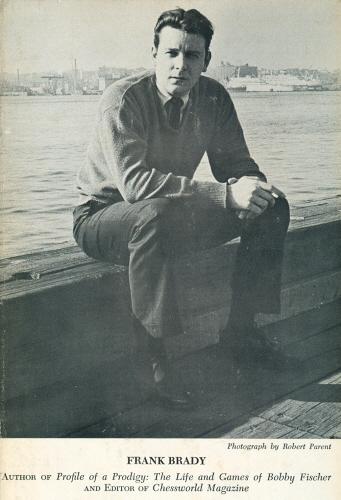

6929. Endgame by Frank Brady

The book Endgame by Frank Brady (New York, 2011) thanks us for assistance but should not.

On 1 December 2010, the day after receiving an ‘uncorrected proof’ of the book from Dr Brady, we spontaneously sent him a list (several pages long) of errors noted during our quick skim of the work. He at once forwarded our list to the publisher, but it proved too late for the corrections to be incorporated. However, the publisher did mistakenly add the acknowledgement to us which Dr Brady had also submitted.

[Addendum: The above statement was posted on the basis of information provided to us by Dr Brady and with his prior knowledge. Subsequently, it became apparent that the publisher had, in fact, been able to incorporate many of the more ‘straightforward’ typographical matters which we had pointed out.]

6930. Annotating while playing

From page 91 of The Chess Masters on Winning Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1960):

‘Tartakower had a fluent pen; he wrote voluminously, often annotating a game for a newspaper or magazine while he was playing it.’

Is any further information available about this alleged practice?

6931. Safety alarm

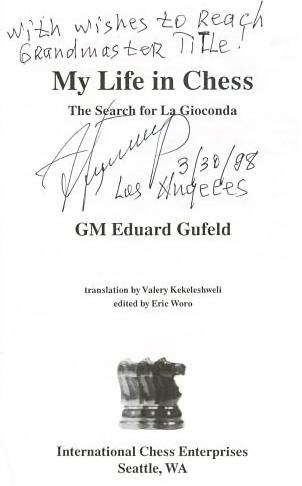

Knud Lysdal (Grindsted, Denmark) wonders what is known about an incident concerning Eduard Gufeld related on page 187 of The Reliable Past by Genna Sosonko (Alkmaar, 2003):

‘In December 2001 in Las Vegas, in one of his last tournaments, Edik, on finding himself in a critical position, resorted to a last chance, pressing the button of the safety alarm, which happened to be on the wall above the head of his opponent, who was completely enraged and lost all his orientation in time trouble.’

From our collection:

6932. Walter Benjamin and Bertolt Brecht

Andrew McGettigan (London) draws attention to an article about Benjamin and Brecht which he contributed on pages 62-64 of the May-June 2010 issue of Radical Philosophy.

6933. Rice game (C.N. 6923)

We now note that the game in question is on pages 637-638 of the April-May 1898 issue of the American Chess Magazine, being one of two ‘recent specimens’ of the Rice Gambit won by Isaac L. Rice against J.M. Hanham.

Henk Smout (Leiden, the Netherlands) mentions that the score was on pages 42-43 of the fifth edition of The Rice Gambit by Emanuel Lasker (New York, 1910), without any date but introduced thus:

‘In the following game that played a great part in the early evolution of the Rice Gambit, and which is very interesting per se, the white pieces were conducted by Mr Rice against Major Hanham.’

From the above-mentioned item in the American Chess Magazine we add a loss by S. Lipschütz to I.E. Orchard (no exact occasion specified):

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6 8 O-O Bxe5 9 Re1 Qe7 10 c3 g3 11 d4 Ng4 12 Nd2 Qxh4 13 Nf3 Qh6 14 Qa4+ c6 15 Bb3 Nf2 16 Kf1 Qh1+ 17 Ke2 Qxg2 18 Rg1

18...Qxf3+ ‘White is now led a merry race to the end. (The charming problem is – Black to win back the queen and victory in seven moves.)’ 19 Kxf3 Bg4+ 20 Kg2 f3+ 21 Kf1 Bh3+ 22 Ke1 Nd3+ 23 Kd2 Bf4+ 24 Kxd3 (The notes in the magazine, which were taken from the New Orleans States, made no mention of 24 Kc2.) 24...Bf5+ 25 Kc4

25...b5+ 26 White resigns. ‘It must have been a new sensation to our analytical Lipschütz to be cuffed about in this unceremonious fashion.’

6934. Master Prim

This photograph of James Whitfield Ellison comes from the dust-jacket of his chess novel Master Prim (London, 1968).

Pages 189-198 included a 29-move game between Julian Prim and Eugene Berlin, and that part of the story was reproduced on pages 143-146 of A Book of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1973). Alexander did not identify the game, which was Alekhine v Sterk, Budapest, 1921.

C.N. 2830 (see pages 2-3 of Chess Facts and Fables)

discussed that brilliancy prize game, noting that

Alekhine’s first volume of Best Games contracted

it by one move.

6935. Houghteling (C.N. 6925)

Dodge v Houghteling

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘According to the 1900 US census, Jay R. Houghteling was born in 1872 in Illinois and was living in Chicago at that time. He had a wife (Helen) and a son (Harold). His occupation was given as “school teacher”.

The US census lists him again (estimated year of birth: 1871). He was still living in Chicago with his wife Helen. His occupation was stated to be “school principal”.

He died on 11 April 1953 in St Petersburg, FL, and this obituary was published in the St Petersburg Times the following day:

“Jay Houghteling

Retired Principal

Jay R. Houghteling, 81, retired principal with the Chicago public school system, died yesterday morning in a local hospital.

Mr Houghteling came here 17 years ago from Chicago and made his home at 1121 Highland Street North. He was a member of the Mirror Lake Shuffleboard Club and honorary member of the St Petersburg Chess Club.

Surviving Mr Houghteling are his wife, Helen, St Petersburg, and two daughters, Mrs Ira Andrews, Oak Park, Ill., and Mrs Arthur Uhler, Chicago.

Friends may call today at Baynard’s Chapel. Interment will be later in Forest Park, Ill.”

Page of the 24 April 1913 edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle gave the same problem by Houghteling which was discussed on pages 42-43 of the February 1921 American Chess Bulletin and was mentioned in C.N. 6925:

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle stated:

“The foregoing problem by Jay R. Houghteling, long known as a strong, practical player, and now the president of the Chicago Chess and Checkers Club, appeared first in the Chicago Tribune of 20 April, and is spoken of in terms of the highest praise by Harry F. Lee, the chess editor. It appears that it is only the second attempt of the Chicago expert, and yet a composition of such genuine merit that Mr Lee confidently believes it will be accepted as a masterpiece.”’

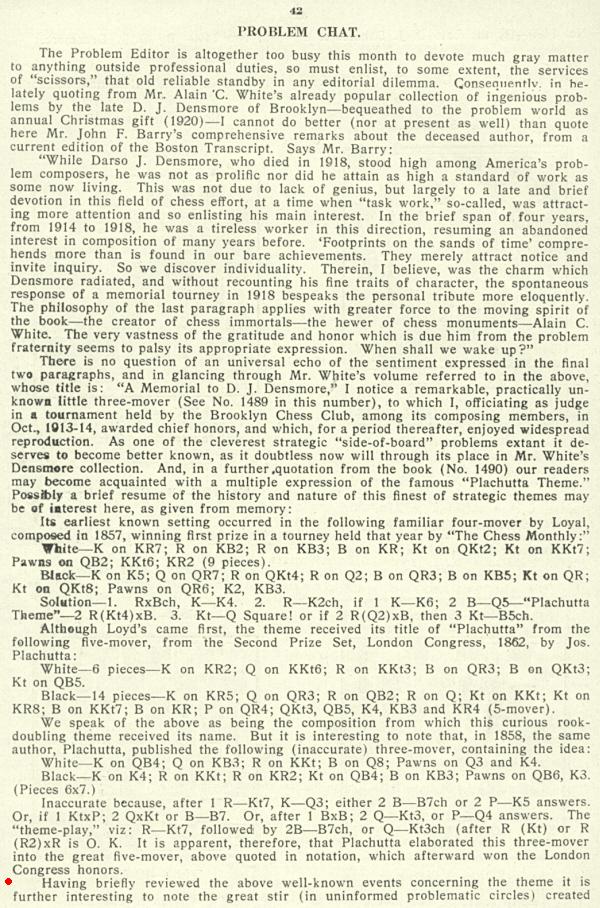

Below is the feature on pages 42-43 of the February 1921 issue of the American Chess Bulletin, which begins with some background information about the Plachutta theme:

In the Houghteling position the white bishop on b2 was unmentioned, and a black rook was placed on d3 rather than d1.

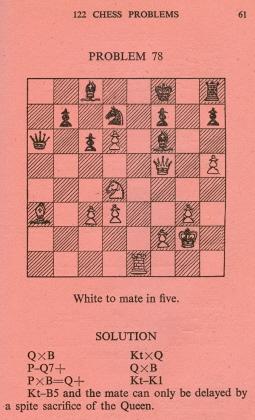

We also note a problem by ‘Jay R. Houghteling, St Petersburg, Fla (First Attempt)’ on page 217 of the October 1939 Chess Review:

Mate in five

The solution was given on page 266 of the December 1939 issue.

6936. Kreisler and Schelling

From page 9 of the January-February 1950 American Chess Bulletin:

‘... There came to light the other day a memorandum in the handwriting of the late Frank Melville Teed, dated 6 September 1915. Back in the 80s, he was treasurer of the Manhattan Chess Club and a member of the Steinitz-Zukertort match committee. He was one of the strongest players of that time and a composer of chess problems. The note read:

“Just a note of interest to those who like both chess and music. See Musical Courier of 2 September, page 9, for photo of Fritz Kreisler and Ernest Schelling, playing chess at Bar Harbor, and watched by Schelling’s dog. (Too bad a chessboard isn’t large enough to include a K9 square) – F.M.T.”’

Does any reader have access to that issue of Musical Courier?

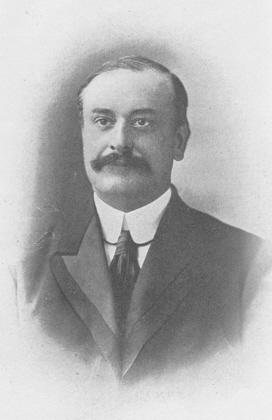

The photograph of Teed given below accompanied his obituary on page 144 of the July-August 1929 American Chess Bulletin:

6937. Pickwickian notes

Charles Dickens and Chess mentions that the game Piper v Davie was annotated on pages 394-396 of the December 1916 BCM with quotations from The Pickwick Papers.

We add that pages 119-120 of the May-June 1915 American Chess Bulletin reproduced from the Family Herald an article ‘Great Pickwickian Discovery’, comprising a game (J.H.B. v S. Pickwick) which also had annotations in the form of quotes from Dickens’ novel.

The game, not identified in the article, was Blackburne v N.N., Canterbury, 1903. We gave it in C.N. 182, with Blackburne’s notes from page 392 of the September 1903 BCM. See pages 31-32 of Chess Explorations.

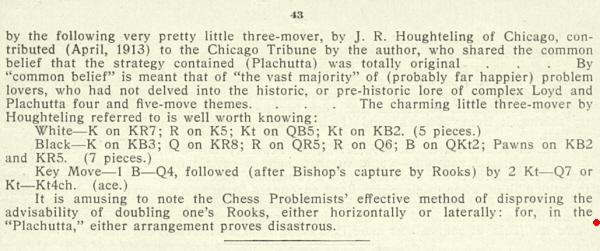

6938. Falkbeer Counter-Gambit

Page 94 of Chess Openings by F.J. Marshall (Leeds, 1904):

Position after 10 Bg2 Be6

A comment by W.H.S. Monck was published on page 131 of the February 1910 Chess Amateur:

The Chess Amateur reverted to the subject when reviewing Griffith and White’s Modern Chess Openings (Leeds, 1911) on page 515 of the February 1912 issue:

‘... In the Chess Amateur Mr Monck complained of having been misled by Marshall’s Chess Openings in a variation of the Falkbeer Counter-Gambit, in which the master had left off with a remark that Black had the best of it when in fact the loss of a piece could not be avoided. This variation is given without comment p. 59 col. 25. We should wish to know how the able authors would reply to the obvious move 11 PxP.’

Page 69 of the second edition of Modern Chess Openings (London, 1913) had no mention of 10...Be6, giving instead (after 10 Bg2) the line 10...Qf7 11 Nxe4 fxe4 12 Bxe4 Bh4+ (13 Kd1 Be6) and referring to the 1902 consultation game opposing von Bardeleben and Pillsbury.

William Henry Stanley Monck, incidentally, was an eminent astronomer, as mentioned on page 153 of Chess Facts and Fables.

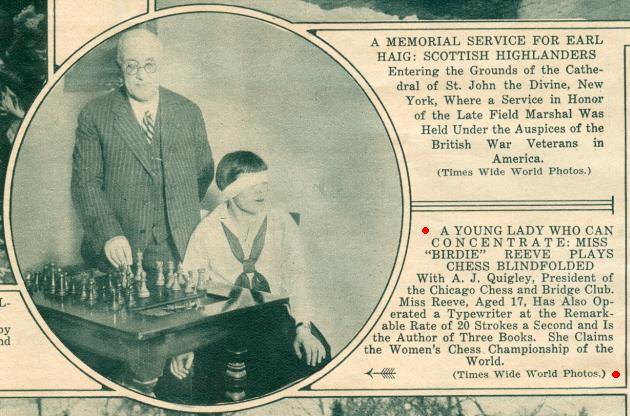

6939. Birdie Reeve

Claims, as opposed to facts, about Birdie Reeve continue to come to light. We have now found that the photograph given in C.N. 6847 was published on page 16 of the Mid-Week Pictorial, 3 March 1928. Its caption asserted that she was aged 17, could type at the rate of 20 strokes a second, was the author of three books and claimed to be the women’s world chess champion:

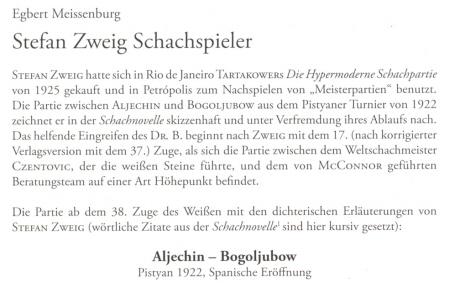

6940. Stefan Zweig and chess

From Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA):

‘While observing a game of chess, a character in Stefan Zweig’s Schachnovelle (Buenos Aires, 1942) points out its similarity to Alekhine v Bogoljubow, Bad Pistyan, 1922. In fact, beginning with 38...Kh7 the game described in Zweig’s novella appears identical to that game.

I find it interesting that Zweig was inspired to use the Alekhine v Bogoljubow game as a model, and I wonder what his source for this game might have been. There appears to be no obvious connection between the text on pages 33-37 of the Suhrkamp Verlag edition of Schachnovelle (Frankfurt, 2001) and the game’s annotations found on either page 139 of the tournament book or pages 84-85 of Tartakower’s Die hypermoderne Schachpartie.

Zweig’s source may have been another book of collected games. We learn that the aforementioned character had become familiar with this game through his study of “ein Schachrepetitorium, eine Sammlung von hundertfünfzig Meisterpartien” (page 64), and in a letter written in Petrópolis, Brazil on 29 September 1941 and quoted on page 111 of Siegfried Unseld’s afterword, Zweig writes:

“... habe eine kleine Schachnovelle entworfen, angeregt davon, daß ich mir für die Abgeschiedenheit ein Schachbuch gekauft habe und täglich die Partien der großen Meister nachspiele.”

Can a likely source be identified?’

The matter was discussed in detail in an article ‘Stefan Zweig Schachspieler’ by Egbert Meissenburg on pages 20-28 of 65 Jahre Schachnovelle edited by S. Poldauf and A. Saremba (Berlin, 2007):

6941. Evans Gambit/German Game

Wanted: more information in connection with this item on page 348 of the September 1915 Chess Amateur:

‘The Evans should be called the German Game

A correspondent in one of the leading German chess magazines suggests that the opening invented by the English captain, Evans, should in future be called the German Game. The Yorkshire Observer Budget comments:

“If the Germans choose to proclaim the whole of the chess openings a sort of military area and forbid anyone else to operate therein, there is no reason why they should not do so. It might please them, and would not make the least atom of difference to the rest of the world.’

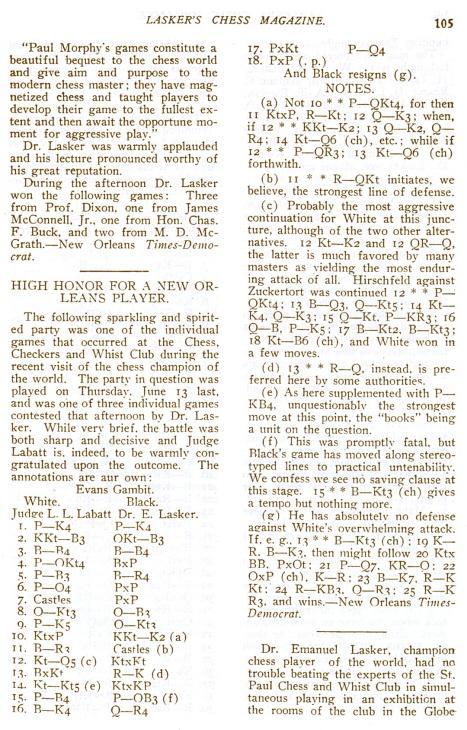

6942. Evans Gambit loss by Lasker

A well-known brevity (1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Ba5 6 d4 exd4 7 O-O dxc3 8 Qb3 Qf6 9 e5 Qg6 10 Nxc3 Nge7 11 Ba3 O-O 12 Nd5 Nxd5 13 Bxd5 Re8 14 Ng5 Nxe5 15 f4 c6 16 Be4 Qh5 17 fxe5 d5 18 exd6 Resigns) won by Judge Leon L. Labatt against Emanuel Lasker in New Orleans in 1907 is often said to have occurred in a simultaneous exhibition. See, for example, page 68 of Play The Evans Gambit by T. Harding and B. Cafferty (London, 1997), as well as various blind-leading-the-blind database productions.

In reality, it was an individual game, as specified on page 105 of the July 1907 issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine:

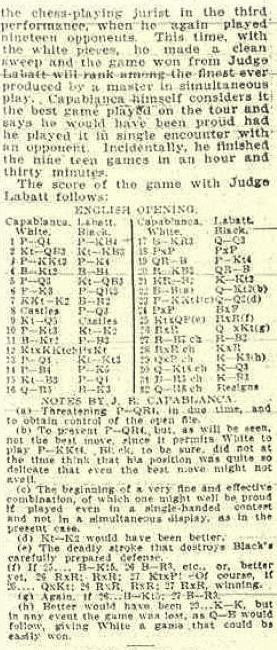

6943. Capablanca v Labatt

Some clarifications are offered regarding Capablanca’s

victory over Leon L. Labatt in a simultaneous display in

New Orleans in April 1915. Pages 61-62 of Het Schaakphenomeen

José Raoul Capablanca y Graupera by M. Euwe and

L. Prins (The Hague, 1949) stated that the Cuban had

described it as one of the finest games ever played in a

simultaneous exhibition and that he would have been

proud to play it against a single opponent. See also

pages 151-152 of The Unknown Capablanca by D.

Hooper and D. Brandreth (London, 1975), which gave

Capablanca’s notes to the game, taken (but also adapted)

from pages 114-115 of the May-June 1915 American

Chess Bulletin. The Cuban’s annotations in the Bulletin

were, in turn, slightly different from what had appeared

on page 3 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of 22

April 1915, and for the record we show that earlier

version:

1 c4 f5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 g3 e5 4 Bg2 Bc5 5 d3 Nc6 6 e3 a6 7 Nge2 Ba7 8 O-O d6 9 Nd5 O-O 10 b3 Ne7 11 Bb2 c6 12 Nxf6+ gxf6 13 d4 Ng6 14 f4 e4 15 Nc3 d5 16 Qh5 Be6 17 Bh3 Qd7 18 cxd5 cxd5 19 Rac1 b5 20 Rf2 Rac8 21 Rfc2 Kg7 22 Bf1 (‘Threatening a4, in due time, and to obtain control of the open file.’) 22...Qb7 (‘To prevent a4, but, as will be seen, not the best move, since it permits White to play g4. Black, to be sure, did not at the time think that his position was quite so delicate that even the best move might not avail.’) 23 g4 (‘The beginning of a very fine and effective combination, of which one might well be proud if played even in a single-handed contest and not in a simultaneous display, as in the present case.’) 23...Qd7 (23....Ne7 would have been better.’) 24 gxf5 Bxf5

25 Nxd5 (‘The deadly stroke that destroys Black’s carefully prepared defense.’) 25...Rxc2 (‘If 25...Bg4 26 Bh3, etc, or, better yet, 26 Rxc8 Rxc8 27 Nxf6! Of course, if 26...Qxd5 27 Rxc8 Rxc8 28 Rxc8, winning.’) 26 Rxc2 Qxd5 (‘Again, if 26...Bg4 27 Bh3.’) 27 Rc7+ Rf7 28 Rxf7+ Kxf7 29 Qxh7+ Ke6 (‘Better would have been 29...Ke8, but in any event the game was lost, as 30 Qxa7 would follow, giving White a game that could be easily won.’) 30 Qg8+ Kd6 31 Ba3+ Kc6 32 Qa8+ Resigns.

A slightly different version of the notes was on page 258 of the July 1915 BCM, although credited to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The introduction to the game in the BCM included this remark: ‘The Cuban master is reported to have stated that he considers it will rank amongst the finest games ever produced in simultaneous chess and he would have been proud had he produced it against a single opponent.’ However, the cutting above shows that the observation ‘will rank among the finest ever produced by a master in simultaneous play’ was not by Capablanca.

We wonder whether the game has ever been annotated in detail. Concerning the exact date, further verification is needed. The Cuban gave three simultaneous displays in New Orleans in April 1915. The Unknown Capablanca (page 151) put 6 April 1915 as the date of the win over Labatt, and the table on page 187 recorded a score of +16 –0 =0 in that exhibition. However, the above newspaper report states that Capablanca won all 19 games, and 19 is also the figure given for that third display on page 114 of the May-June 1915 American Chess Bulletin. Page 224 of the August 1915 issue of La Stratégie had the heading ‘Jouée le avril dans une séance de parties simultanées’. Unsurprisingly, Rogelio Caparrós’ anthology of Capablanca games was far from helpful. Pages 210-211 of the 1991 edition gave the game-score twice, with different dates (6 April 1915 and 9 May 1915). The 1994 (‘revised’) edition had the game once only (on page 196) and plumped for 9 May 1915, i.e. more than a fortnight after the game had appeared in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

6944. An old trick

Thomas Binder (Berlin) reverts to a subject raised in C.N. 6452: stories about preventing a master from obtaining a 100% score in a pair of games through the trick of repeating in the second game his own moves from the first one.

C.N. 6452 quoted an article by Tartakower on pages 48-50 of the February 1927 Wiener Schachzeitung, and we now add an item on page 281 of the July 1884 BCM:

6945. Alekhine’s openings

On page 208 of Combinations The Heart of Chess (New York, 1960) Irving Chernev wrote of Alekhine:

‘His contributions to chess theory are of such importance as to justify saying, “The openings consist of Alekhine’s games with a few variations”.’

The identical words are on page 251 of Chernev’s book The Golden Dozen (Oxford, 1976).

Had the sentiments in double quotation marks been expressed by someone else before 1960 or can they legitimately be attributed to Chernev?

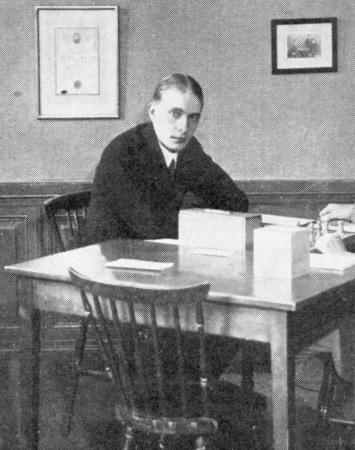

This fine photograph of Alekhine is from page 250 of The Golden Dozen. It is not difficult to identify the game in progress, but a clue is offered: Alekhine’s opponent was discussed in C.N. 3809.

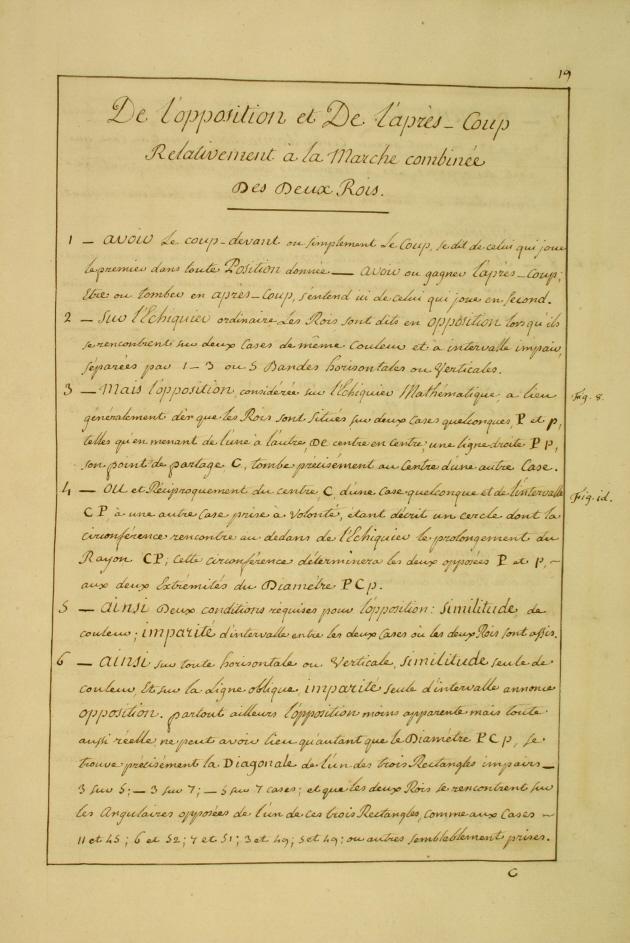

6946. Opposition (C.N.s 6869, 6905 & 6918)

From Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) comes the first page of the chapter in Chapais’ manuscript Essais analytiques (circa 1780) which deals with the opposition:

6947. Ståhlberg’s elegant style

Gideon Ståhlberg

‘Nobody amongst living players has such an elegance of style as Ståhlberg when playing at his best.’

Harry Golombek expressed that view on page 124 of a book which he translated and edited: Ståhlberg’s Chess and Chessmasters (London, 1955). He also praised the Swedish master’s style in his obituary on pages 230-231 of the August 1967 BCM:

‘... It is apparent that he was one of the most active and successful tournament players of our time and certainly the most successful Swedish player of all time. But more important is the style in which he played and achieved these results. Style is the operative word in his case; elegant, cultivated, correct, and always with an additional spice of imagination and originality, his was a style that was at once pleasing and effective.’

We shall welcome other authoritative observations which single out particular masters for the elegance of their play.

6948. Amsterdam, 1950

A group photograph from opposite page 16 of Wereldschaaktoernooi

Amsterdam

1950 by M. Euwe and L. Prins (Lochem, 1951):

As shown in C.N. 3577, our copy of the book was signed by all 20 participants in the tournament.

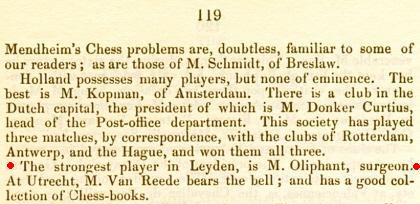

6949. Oliphant (C.N. 6895)

From Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany):

‘Pages 118-120 of the February 1838 issue of The Philidorian had an article “Continental Chess-Clubs, and Players” which stated (on page 119): “The strongest player in Leyden, is M. Oliphant, surgeon.” M. stands for “Monsieur”, and I assume that this is the man who played at Amsterdam, 1851 and whose profession was given as “pharmacist” by your correspondent Peter de Jong in C.N. 5416.’

6950. Who?

A familiar chess name ...

6951. Boris Kostić and Enrico Caruso

On pages 32-33 of the 5/2004 New in Chess Boris Spassky mentioned in an interview that at one time Enrico Caruso’s entourage included Boris Kostić.

Kostić took up residence in the United States in the first half of 1915, as reported on page 108 of the May-June 1915 American Chess Bulletin. His contact with Caruso was related on pages 34-35 of Ambasador Šaha by D. Bućan, P. Trifunović and A. Božić (Belgrade, 1966) and on pages 33-35 of Ambasador Šaha by D. Bućan (Novi Sad, 1987), and we shall be grateful if a reader can assist us in extracting the hard facts from those two accounts.

Neither book gave any games played between Kostić and Caruso, but on pages 93-94 of Chess to Enjoy (New York, 1978) A. Soltis wrote:

‘One of the most aggressive players in the musical world was Enrico Caruso, who took the game seriously enough to study under Boris Kostić, the first great Yugoslav player. Here is one of their many skittles or offhand games with the mighty tenor playing Black.’

The moves, presented with the customary Soltis sourcelessness, were: 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 Nbd7 5 Bg5 Bb4 6 e3 c5 7 Qc2 Qa5 8 Bxf6 Nxf6 9 Nd2 cxd4 10 exd4 O-O 11 a3 e5 12 dxe5 d4 13 Nb5 a6 14 exf6 Re8+ 15 Kd1 axb5 16 fxg7 Bxd2 17 Qxd2 Qa4+ 18 Kc1 bxc4 19 Be2 c3 20 Qd1 Qa5 21 Bd3 cxb2+ 22 Kxb2 Qc3+ 23 Kb1 Re6 24 Bxh7+ Kxh7 25 White resigns.

No place or date was stipulated, but when B. Pandolfini gave the conclusion on page 106 of Treasure Chess (New York, 2007) he put ‘1918’. In some databases (as well as on page 55 of CHESS, September 2004) ‘New York, 1923’ is specified – even though Caruso died in 1921.

6952. The 23 Ng5 affair (Skipworth v

Zukertort)

Below is an article by G.H. Diggle which was originally published in the October 1977 Newsflash and is on page 27 of the anthology Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

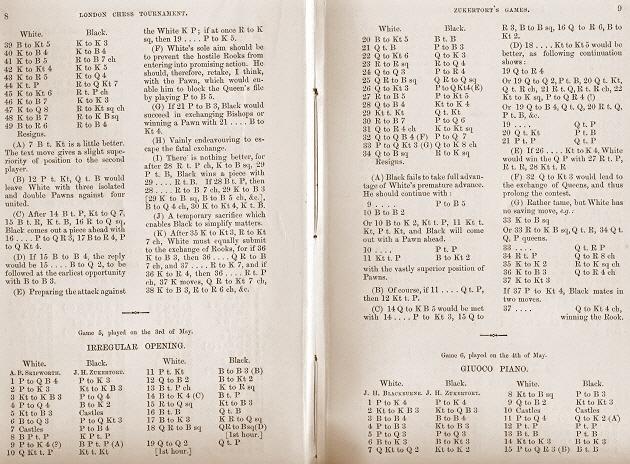

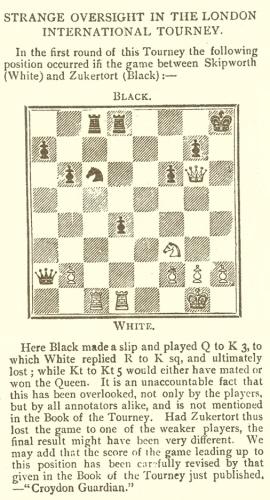

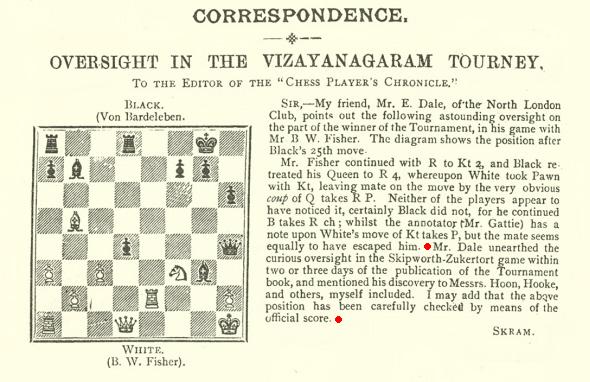

‘Zukertort’s tremendous tournament victory of London, 1883 (first with 22 points out of 26 and three clear points ahead of anyone else) is as well known as his famous win against Blackburne in the sixth round of the Tournament, Zukertort having already started off with five successive wins. What is not so well known now, and what was never discovered then until months afterwards, was that in the fifth of these wins, against Rev. A.B. Skipworth, Zukertort had on his 22nd move committed a disastrous blunder and his opponent never saw it. The position was:

Here Zukertort (a pawn up) played 22...Q-K3?? and Skipworth replied 23 R-Rl?? whereas 23 N-N5 would have mated or won the queen in two moves. Amazingly, though the Tournament Room was crowded with pressmen and “strong lookers-on”, “no dog barked or night-owl screeched” – more incredible still, Zukertort himself (who annotated his own games in the Book of the Tournament) “missed it” again, passing over both “howlers” without even an “?”. But finally, many months later, an obscure Badmaster named Mr Marks, who was then Secretary of the Athenaeum Chess Club, and had purchased the Tournament Book, made the “chess scoop” of his life and “informed the Press”, clearly demonstrating Uriah Heep’s claim that while “great scholars are often as blind as a brickbat, us ’umble ones has got eyes in our ’eds”.

Had Skipworth won this game, what would have been the effect on Zukertort, a fragile man and “a bag of nerves”? Thrown off balance after a magnificent start by an absurd loss against one of his weakest opponents, would he ever have won that brilliant game against Blackburne in the very next round? And Skipworth? He retired through ill-health halfway through after three wins and nine losses. This was criticized; but the trouble was that he was Rector of the Lincolnshire village of Tetford, six miles from Horncastle and 150 from London, and he could not find a cleric to stand in for him on Sundays. Consequently, during the Tournament he had to go to and fro at weekends, getting up at the crack of dawn on Monday mornings, driving by horse and trap to Horncastle, proceeding by slow train via Woodhall Junction, Boston and Spalding to Peterborough, and thence to King’s Cross to be ready for his game at the Criterion, Piccadilly at 12 noon. This, on top of the strain of tournament play, proved too much for him. At his best (the late J.H. Blake once told the BM) Skipworth was “hot stuff” and both he and Thorold “had a magnificent eye for a combination”.’

Here is the game as it appeared on pages 8-9 of the tournament book, with Zukertort’s notes:

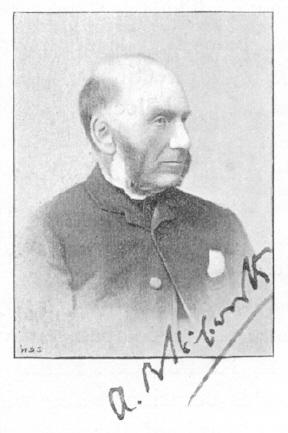

Arthur Bolland Skipworth

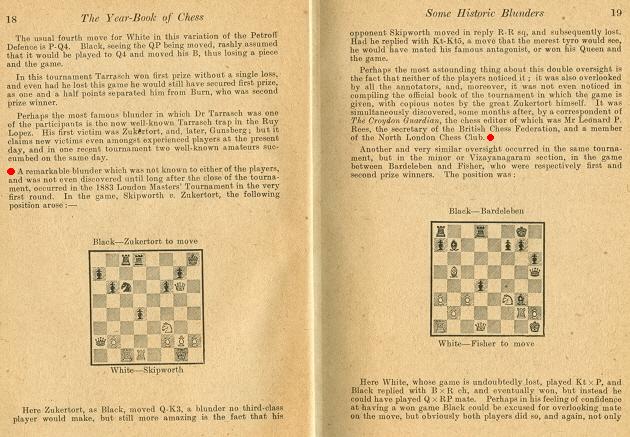

The ‘23 Ng5 affair’, as we are calling it, was discussed by W.H. Watts in an article entitled ‘Some Historic Chess Blunders’ in the Christmas 1914 issue of The Strand Magazine. The article was reproduced on pages 107-109 of the January 1915 Chess Amateur, and a lengthier version was published on pages of The Year-Book of Chess 1915 and 1916 (London, 1917), which Watts co-edited with A.W. Foster. From the Year-Book:

We have found this item on page 248 of the 2 January 1884 issue of the Chess Player’s Chronicle:

In the light of G.H. Diggle’s reference to ‘Mr Marks’ it is particularly relevant (though also puzzling) to note that a subsequent issue of the Chronicle (16 January 1884, page 258) had a letter from Edward Marks (using his obvious pseudonym, ‘Skram’) which discussed Fisher v von Bardeleben (see pages 227-228 of Chess Facts and Fables) and Skipworth v Zukertort but made no claim for himself regarding the discoveries:

Further information is sought concerning W.H. Watts’ statement that the possibility of 23 Ng5 ‘was also overlooked by all the annotators’ of the time (i.e. before the tournament book appeared). Page 65 of the November 1883 Chess Monthly announced that the book would be available by the end of that month. (It may be significant to add that page 72 of the same issue reported that Zukertort had sailed for the United States on 20 October.) Where was the Skipworth v Zukertort game published between the date on which it was played (3 May 1883) and the end of November 1883? We ask that question not merely to verify Watts’ words ‘overlooked by all the annotators’ but also, and above all, to ascertain whether the game-score published in any earlier sources was identical to what appeared in the tournament book.

According to the tournament book, the preceding play ...

... went 19 Qd2 Qxa2 20 Bg5 Bxg5 21 Qxg5 f6 22 Qg6 Qe6 23 Ra1. Is it really likely that White played Ra1 when the black queen was no longer at a2?

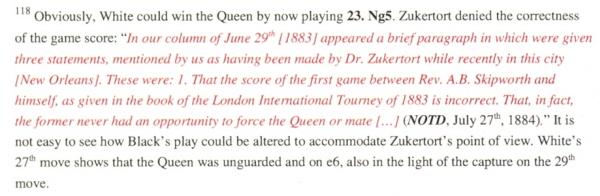

Finally for now, we draw attention to an important footnote on page 124 of The International Chess Tournament London 1883 in letters by William Steinitz introduced and edited by Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, 2010). It mentions a report in the New Orleans Times-Democrat of a claim by Zukertort that the tournament book was wrong:

In the second line [1883] should read [1884]; we should particularly like to see those Times-Democrat columns and present them in a future C.N. item.

Much further investigation of the 23 Ng5 affair is clearly needed.

6953. Timidity

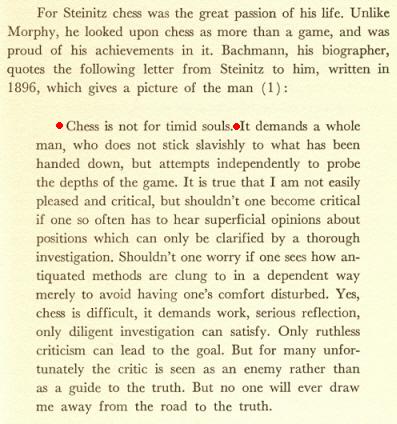

‘What is the best thing that was ever said about chess?’ is a question put to Garry Kasparov on page 105 of the 1/2011 New in Chess. His reply:

‘“Chess is not for timid souls” – Steinitz.’

That is one of those innumerable quotes which chess books and webpages include ad nauseam without attempting to offer a reliable source.

We note the following on page 45 of Psychoanalytic Observations on Chess and Chess Masters by Reuben Fine (New York, 1956):

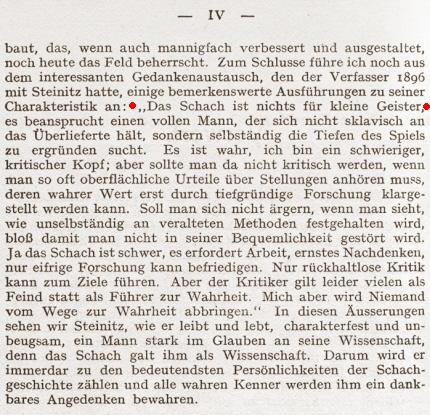

That is a translation of a passage on page iv of volume four of Schachmeister Steinitz by Ludwig Bachmann (Ansbach, 1921):

However, ‘chess is not for timid souls’ seems a decidedly free/loose rendering of ‘Das Schach ist nichts für kleine Geister’ (a sentence which, though, is difficult to translate precisely). We can offer no occurrence of the specific wording ‘Chess is not for timid souls’ in any of Steinitz’s English-language writings.

Below are some comparable sightings of the word ‘timid’ elsewhere:

‘The first time I saw this game [A.R. Krogius v I. Niemelä, Loviisa, 1934] I wrote: “Chess, contrary to the impression held in some quarters, is not a game for timid souls.”’ Fred Reinfeld, Great Brilliancy Prize Games of the Chess Masters (New York, 1961), page 186.

‘Chess is not for the timid.’ Irving Chernev, 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955), page 125.

‘A hundred years ago chess was no game for the timid.’ Irving Chernev, Chess Review, November 1944, page 27.

On the other hand, Chernev gave the ‘chess is not for

timid souls’ remark with a mention of Steinitz and

Bachmann in his notes to game three in Logical Chess

Move by Move (first published in 1957).

Other variants (e.g. with the word ‘faint-hearted’) are also available. See, for instance, Karpov’s observation on page 261 of Anatoly Karpov: Chess is My Life by A. Karpov and A. Roshal (Oxford, 1980).

6954. Weil/Weill/Wiel

The Factfinder lists a number of C.N. items which have discussed an obscure nineteenth-century chess figure named G(ottlieb) Weil, or perhaps Wiel.

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) adds these references:

- A problem by ‘Herr Weil’ in the Chess Player, 9 August 1851, page 31;

- The game Zytogorski v Weil, won by the former, in the 13 September 1851 issue of the same magazine, page 72;

- A player named Weil (or Weill) participated in a match between the City of London Club and the Westminster Club in 1871 (Westminster Papers, 1 July 1871, pages 44 and 47). On page 44 he was referred to as ‘Dr Weill’, but on page 47, where his win against Frankenstein in that match was given, his name appeared as ‘Mr Weil’.

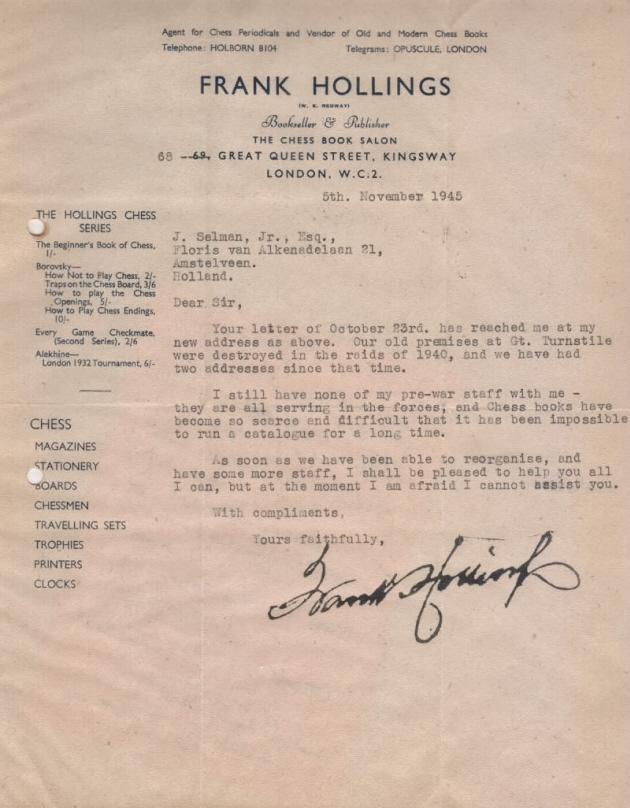

6955. Frank Hollings

Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) submits this letter:

Can it really be that the Frank Hollings was still alive and working in 1945?

The letter adds a further twist to a much-discussed mystery, and we have brought together the previous material in a feature article The Frank Hollings Conundrum.

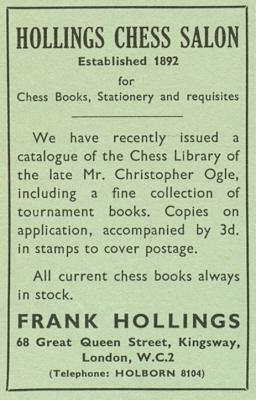

6956. Christopher Ogle

This advertisement on an inside cover page of the October 1956 BCM states that the Hollings Chess Salon was established in 1892, but we are also intrigued by the reference to ‘a catalogue of the Chess Library of the late Mr Christopher Ogle’. Does any reader have a copy of that catalogue?

Our interest in Ogle was prompted many years ago by the

well-known anecdote regarding London, 1922, and for ease

of reference C.N. 3083 is reproduced here:

If chess literature is to feature anecdotes, let them at least have a point. One story, set during the London, 1922 tournament, which has some purpose was related by David Hooper in the Capablanca entry of Anne Sunnucks’ Encyclopaedia of Chess:

‘These two rivals [Capablanca and Alekhine] were taken to a variety show by a patron, Mr Ogle, who recalled that Capablanca never took his eyes off the chorus, whilst Alekhine never looked up from his pocket chess set.’

In the first edition of The Oxford Companion to Chess (the Alekhine entry) the patron was named in full as Christopher Ogle, and in at least one other modern outlet he has been described as a ‘chess patron’. That remains to be demonstrated, but our particular interest is in knowing the source of the Ogle/ogling recollection and whether there are further reminiscences from London, 1922.

6957.

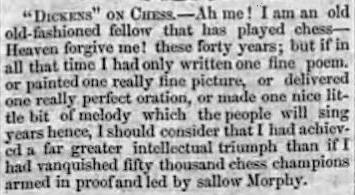

Dickens, chess and Morphy

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) points out a brief item on page 1 of the Weekly Georgian Telegraph of 28 June 1859:

Pending further information, this paragraph, referring to Dickens, chess and Morphy, needs to be treated cautiously, and not least because our correspondent has found that the same text had appeared on page 3 of the Washington Constitution of 14 June 1859, but with the quote attributed to ‘Diogenes’.

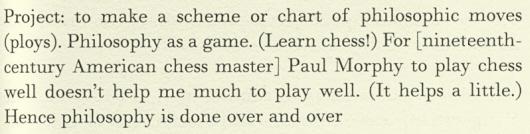

6958. Susan Sontag

There is an unexpected reference to chess and Morphy in Susan Sontag’s journal (part of an entry dated 24 October 1956), as published on pages 82-83 of Reborn edited by David Rieff (New York, 2008):

6959. Young Fischer (C.N.s 4769 & 6193)

Regarding the first photographs of Fischer, C.N. 6193 gave two pictures taken in January 1953.

The first page of the plates section in Endgame by Frank Brady (New York, 2011) has ‘the earliest known photograph of Bobby Fischer, sitting on his mother’s lap in 1944, when he was one year old’.

6960. Who? (C.N. 6950)

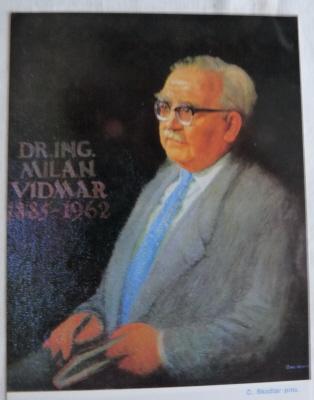

This is Milan Vidmar Jr (1909-80), in a photograph published on page 42 of the February 1950 Chess Review.

6961. Vidmar senior

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) owns a postcard of Milan Vidmar Sr:

The reverse side was signed by participants in one of the Vidmar Memorial tournaments, but the inscriptions are now faint.

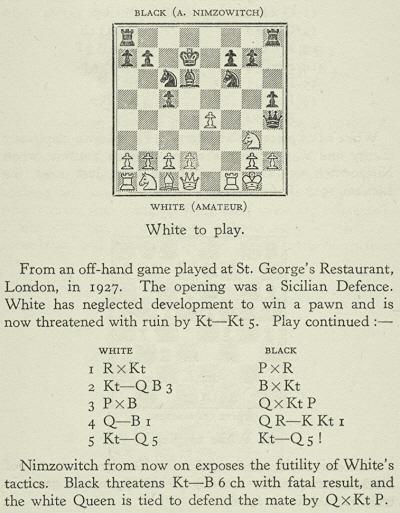

6962. Nimzowitsch snippet (C.N. 2526)

Information would still be welcome concerning a game whose conclusion was given in C.N. 2526 (see page 49 of A Chess Omnibus), our source being pages 83-84 of Learn to play Chess by P. Wenman (Leeds, 1946):

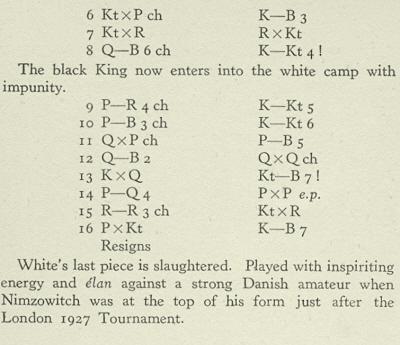

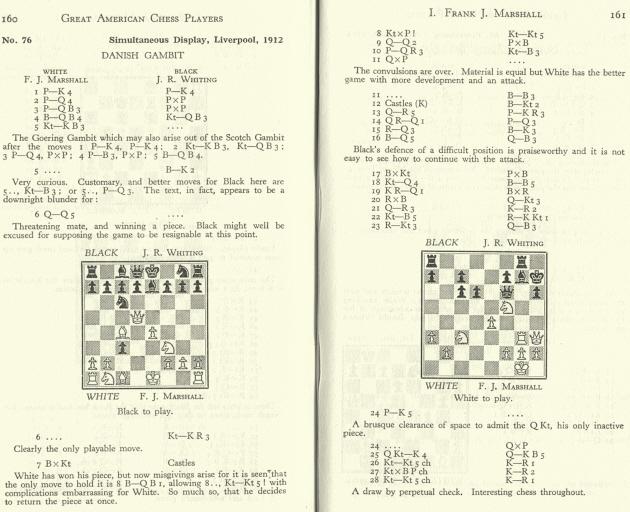

6963. Marshall v Whiting

We also continue to seek a primary source for a game

which Wenman gave on pages 160-161 of his book Frank

J. Marshall (Leeds, 1948):

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Bc4 Nc6 5 Nf3 Be7 6 Qd5 Nh6 7 Bxh6 O-O 8 Nxc3 Nb4 9 Qd2 gxh6 10 a3 Nc6 11 Qxh6 Bf6 12 O-O Bg7 13 Qh5 h6 14 Rad1 d6 15 Rd3 Be6 16 Bd5 Qf6 17 Bxc6 bxc6 18 Nd4 Bc4 19 Rfd1 Bxd3 20 Rxd3 Qg6 21 Qh3 Kh7 22 Nf5 Rg8 23 Rg3 Qf6 24 e5 Qxe5 25 Ne4 Qf4 26 Ng5+ Kh8 27 Nxf7+ Kh7 28 Ng5+ Kh8 Drawn.

The 6 Qd5 line was discussed in C.N.s 3075 and 3076; see page 55 of Chess Facts and Fables.

6964. Endgame

Frank Brady (New York, NY, USA) wonders whether his new biography of Bobby Fischer, Endgame, is the first chess book ever to enter, upon publication, a bestseller list (number 31 on the New York Times list).

He informs us that editions of his earlier Fischer work, Profile of a Prodigy, have sold more than 100,000 copies over the years.

There is an entry ‘Book sales’ in our Factfinder.

Back cover of the dust-jacket of Profile of a Prodigy (London, 1965)

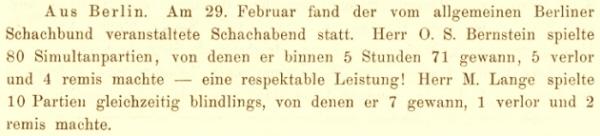

6965. Simultaneous exhibition by Bernstein

Our article Large Simultaneous Displays has a reference to Ossip Bernstein, and further details are added now. On page 8 of his monograph on Bernstein, Moderne Schachstrategie (Breslau, 1930), Tartakower wrote:

‘Bekanntlich war Dr Bernstein von jeher einer der besten und schnellsten Simultanspieler, da er bereits im Jahre 1903 in Berlin mit 80 innerhalb von 5½ Stunden durchgeführten Simultanpartien (Resultat. +70 –4 =6) eine Rekordleistung vollbrachte.’

The correct year would appear to be 1904, a different set of details being given on page 91 of the March 1904 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

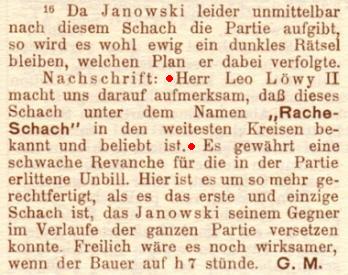

6966. Spite check

C.N.s 3182 and 3186 have been placed online under the heading The Spite Check in Chess, and the present item adds some notes on the origins of the term ‘spite check’.

The first occurrence that we have found in an English-language source is in Alekhine’s New York, 1924 tournament book. In the sixth-round game between Réti and Yates Black’s final move, 30...Rd2+, prompted the annotator to observe: ‘The familiar spite-check.’

The German edition had ‘Das wohlbekannte Racheschach’ (with ‘Un familiar jaque de despecho’ in the Spanish version of the tournament book). Can any instances of ‘spite check’ be found in English chess literature prior to the mid-1920s?

With respect to ‘Racheschach’, we have traced an occurrence on page 365 of the December 1915 Deutsche Schachzeitung. More significantly, there is Georg Marco’s quotation of a statement by Leo Löwy on page 204 of the July-August 1905 Wiener Schachzeitung that ‘Racheschach’ was in common use:

This note was appended to 30 Qc8+ in Janowsky v Marshall, eighth match-game, Paris, 11 February 1905.

6967. Spite sacrifice

From page 140 of the May 1952 BCM, in an article by E.G.R. Cordingley:

‘A spite check or spite sacrifice? The phrase is not mine, but it sounds self-explanatory. A spite sacrifice is one where you give up a piece merely to stave off worse disaster, though it merely prolongs the length, not the result of the game. ... A spite check merely adds to the length of the game and similarly serves no useful purpose.’

The only book in which we recall seeing the term ‘spite sacrifice’ is Cordingley’s 122 Chess Problems, Puzzles, Studies and End Games (undated, but published in London in 1945 or 1946):

6968. Gallows humour

In the early 1990s there were press reports in the United Kingdom (still available on the Internet) about a chess-related case of attempted murder in which the victim was Matthew Hay.

A murderer of the same name was mentioned, with a reference to chess, on page 186 of Scottish Men of Letters in the Eighteenth Century by Henry Grey Graham (London, 1901):

6969. Nimzowitsch snippet (C.N. 6962)

Maurice Carter (Fairborn, OH, USA) reports that the full game-score was published in The Observer (London) of 25 March 1928:

N.N. – Aron NimzowitschLondon, 1927

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Ne2 e5 3 f4 d6 4 fxe5 Nc6 5 Ng3 h5 6 exd6 Bg4 7 Be2 Bxd6 8 Bxg4 Qh4 9 Bd7+ Kxd7 10 O-O Nf6 11 Rxf6 gxf6 12 Nc3 Bxg3 13 hxg3 Qxg3 14 Qf1 Rag8 15 Nd5

15...Nd4 16 Nxf6+ Kc6 17 Nxg8 Rxg8 18 Qf6+

18...Kb5 19 a4+ Kb4 20 c3+ Kb3 21 Qxf7+ c4 22 Qf2 Qxf2+ 23 Kxf2 Nc2 24 d4 cxd3 25 Ra3+ Nxa3 26 bxa3 Kc2, and White resigned a few moves later.

6970. Rules

‘Some excellent rules to follow’ is the title of a section on page 20 of Chess The Game of Kings The King of Games by Lenace L. Fergus (Chicago, 1936). Some of the counsel is standard (‘A rook is powerful on an open file’) or, at least, potentially helpful (‘Try to capture all passed pawns’), but we wonder what should be made of this:

‘Do not capture your opponent’s queen’s pawn with your queen and you will usually profit by it.’

6971. Best books

Some updating of The Very Best Chess Books seems overdue, and readers’ recommendations will be welcome.

6972. Showalter and baseball (C.N.s 4449, 4456, 5700 & 5706)

Several C.N. items have discussed Jackson Whipps Showalter’s alleged connection with baseball, and in C.N. 5706 Kevin Marchese reported that he was writing a book which would demonstrate that the master’s date of birth was 5 February 1859 (and not 5 February 1860, as commonly believed).

Larry Crawford (Milford, CT, USA) takes up both matters:

‘It appears that Mr Marchese is correct that Showalter was born in 1859. A photograph of his plaque in the Georgetown cemetery reads “1859-1935”. Another webpage says that Showalter was born on 5 February 1859 in Minvera, Bracken Co, KY, the information being taken from the “Kentucky Birth Records 1852-1910”. Furthermore, it is stated that the death records covering the period 1852-1953 gave 1860, which suggests that they may be the source of the error.

As regards claims that Showalter invented the curve ball in baseball, William Arthur “Candy” Cummings is widely accepted by baseball experts as the inventor. His Baseball Hall of Fame plaque lists 1867 as the year of the invention, but Cummings maintained that he thought of the idea as early as 1863 and practiced his delivery for years, which put him ahead of other pitchers of the era. His description below is from a reprint of his article in the September 1908 issue of Baseball Magazine (“How I Pitched the First Curve Ball”) on page 33 of The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers by R. Neyer and B. James (New York, 2004):

“In 1867 I, with the [Brooklyn] Excelsior club, went to Boston, where we played the Lowells, the Tri-Mountains, and Harvard clubs. During these games I kept trying to make the ball curve. It was during the Harvard game that I became fully convinced that I had succeeded in doing what all these years I had been striving to do. The batters were missing a lot of balls; I began to watch the flight of the ball through the air, and I distinctly saw it curve.”

In a letter published on page 6 of the New York Times on 21 July 1900 James Gordon Spencer stated that he had played with Cummings for a while in the 1860s and that Cummings was pitching a curve at that time. The New York Clipper of 25 June 1870 (page 90) described a game which Cummings pitched against the Cincinnati Red Stockings:

“... the crowd was on the tip-toe of expectation to see whether George could hit the Star pitcher’s horizontally curved line balls ...”

This information supports Professor Rubinstein’s conclusion in C.N. 4456 that Jackson Whipps Showalter (born in 1859) was too young to have invented the curve ball.

He did, though, have a great liking for the sport. When he arrived late for the start of his 1892 match with Lipschütz, some of the spectators joked that he had decided to stay over in Baltimore to watch a baseball game with Boston. On eventually arriving, Showalter told a reporter that he had merely been delayed on his journey, but he added, “Yes, I am still a great admirer of baseball”. (Source: New York Sun, 19 April 1892, page 4.)’

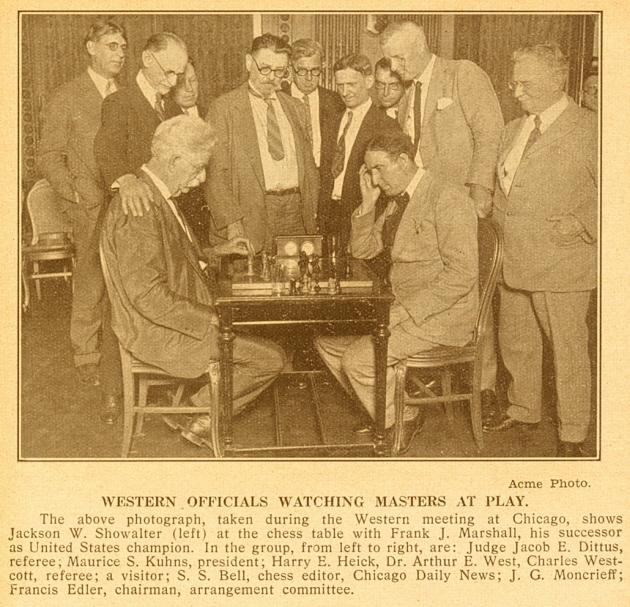

Source: American Chess Bulletin, September-October 1926, page 110

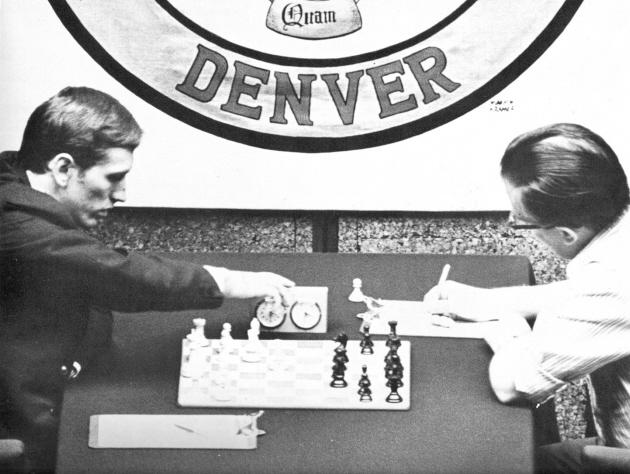

6973. Fischer v Larsen

Ignacio Martínez (Madrid) asks:

‘Who were the seconds of Fischer and Larsen in their 1971 Candidates’ semi-final match? Or did they play in Denver without any team support?’

From Jack Spence’s report ‘Fischer v Larsen: at the ring-side’ on pages 328-329 of CHESS, July 1971:

‘... both players were in Denver without a second, Fischer being accompanied only by Ed Edmondson, USCF official, in charge of arrangements, and Larsen by his wife ...’

The above photograph was on the front cover of the September 1971 Chess Life & Review.

6974. Time-limits

Drawing attention to a brief list (concerning nineteenth-century matches and tournaments) on a Swiss Chess Federation webpage, Ralf Mulde (Bremen, Germany) asks whether a chart exists of the time-limits for major events of all periods.

6975. Alfred Emery

This photograph of ‘Mr Alfred Emery, of The Daily News’ was the frontispiece of the October issue of the BCM, which carried an appreciation of him by F.P. Wildman on pages 429-431. In later years Emery authored a number of books, such as Chess of To-day (London, 1924), but when exactly did he die? The privately-produced 1994 edition of Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia gave the year 1943, but without further details.

6976. Berne, 1932

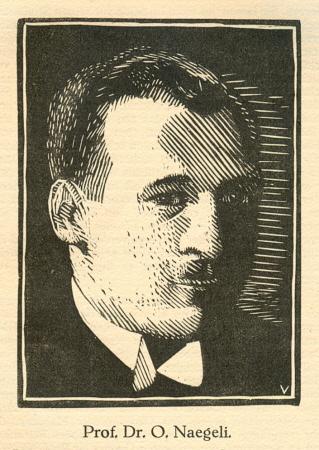

Tony Gillam (Nottingham, England) reports that he has collected five of the six games played in a training tournament in Berne on 25-27 March 1932 (won jointly by Alekhine, Naegeli and Voellmy, with Gygli in bottom position). The missing game-score is from the first round: Naegeli’s victory over Gygli. Does any reader have it?

This woodcut by Erwin Voellmy is from page 27 of his book Schachkämpfer (Basle, 1927):

6977. L. Steiner on S. Tartakower

From an article by Lajos Steiner on pages 212-213 of Chess Review, September 1938:

‘Probably no-one can play more strongly than Tartakower. There are better players, more perfect masters. Tartakower has faults, and the greatest of them is that he does not care to avoid getting into difficult positions. Sometimes his ability enables him to extricate himself safely, other times he is left without recourse. Nobody can handle such positions more cleverly, no matter how they may have happened to come about. If he would put forth such efforts in more suitable positions, he would hardly know his superior. But either he cannot succeed in eliminating this fault (it is very difficult to eliminate fundamental faults) or he does not care to – which amounts to the same thing in the end.’

6978. Pomar and Bernstein (C.N.s 6573, 6584, 6589 & 6609)

Olimpiu G. Urcan notes a Pathé news item on the London, 1946 tournament, featuring Arturo Pomar in play (with the black pieces, as in the photograph above) against Ossip Bernstein, as well as footage of some other players, including Savielly Tartakower (briefly) and William Winter. The technical quality is good, with a commentary which is quintessentially English.

Another Pathé report pointed out by Mr Urcan concerns Jutta Hempel.

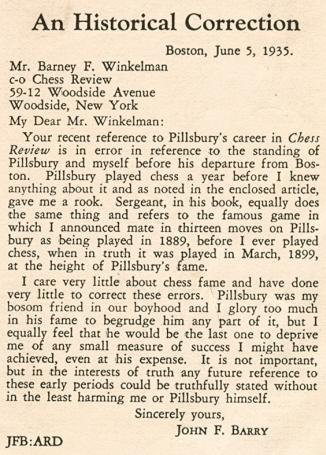

6979. Barry v Pillsbury (C.N. 4582)

White to move

C.N. 4582 remarked that the familiar Barry v Pillsbury game (in which White announced mate in 13 moves) is commonly misdated 1889, instead of 1899.

We add a letter from Barry published on page 185 of the August 1935 Chess Review:

| First column | << previous | Archives [79] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.