Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [80] | next >> | Current column |

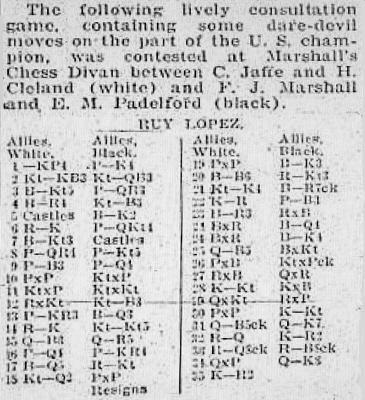

6980. The Marshall Gambit

Charles Jaffe and H.E. Cleland – Frank James Marshall and Edward M. PadelfordNew York, circa 15 February 1918

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 O-O 8 a4 b4 9 c3

9...d5 10 exd5 Nxd5 11 Nxe5 Nxe5 12 Rxe5 Nf6 13 h3 Bd6 14 Re1 Ng4 15 Qf3 Qh4 16 d4

16...h5 17 Bd5 Rb8 18 Nd2 bxc3 19 bxc3 Be6 20 Bc6 Rb6 21 Ne4 Bh2+ 22 Kh1 f6 23 Ba3 Rxc6 24 Bxf8 Bd5 25 Qf5

25...Be5 26 dxe5 Bxe4 27 Rxe4 Nxf2+ 28 Kg1 Qxe4 29 Qxf2 Kxf8 30 exf6 Rxf6 31 Qc5+ Kg8 32 Rd1 Qe2 33 Rd8+ Kh7 34 Qxc7 Rf1+ 35 Kh2 Qe1 36 White resigns.

Source: Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 7 March 1918, page 6:

The game-score has been contributed by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA), who writes:

‘With the moves 8 a4 b4 added, here is Marshall playing his Gambit many months before his encounter with Capablanca (which was played on 23 October 1918). The consultation game probably took place on 15 February 1918 at Marshall’s Chess Divan. That was the day of the third annual dinner, presided over by H.E. Cleland. A rapid transit tournament was also played that day (New York Post, 16 February 1918, page 12; see too the American Chess Bulletin, March 1918, page 53).

It will be noted that Marshall even played 16 (15)...h5, a move discussed in your feature article The Marshall Gambit.’

6981. Gallows humour (C.N. 6968)

Craig Pritchett (Dunbar, Scotland) draws attention to an article (‘Chess and the Common Muir of Ayr Hangman’) which he contributed on page 36 of the June 2008 CHESS.

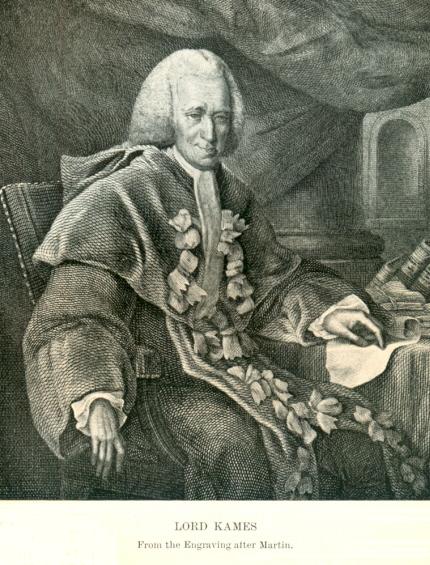

The sources specified in the article suggest that in the eighteenth-century case Matthew Hay stood accused of two murders and that there is much uncertainty over the alleged ‘That’s checkmate ...’ remark by the judge, Lord Kames.

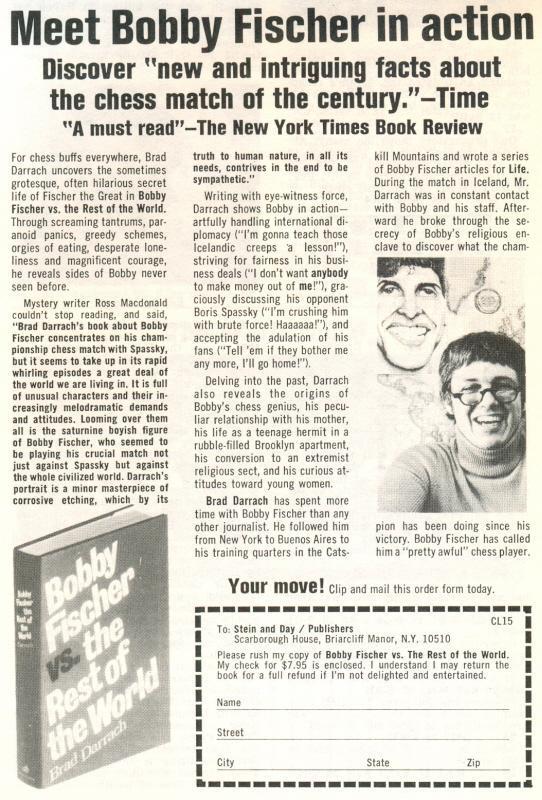

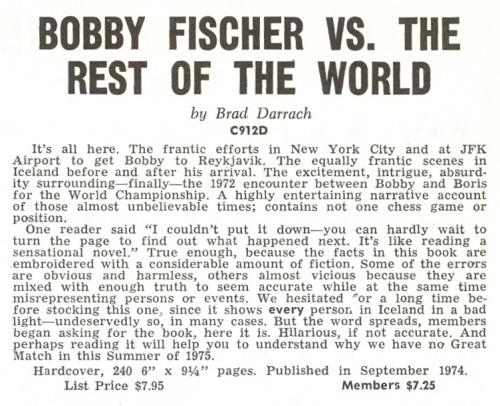

6982. Fischer v

Darrach et al.

Further to our ChessBase article on Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World by Brad Darrach (New York, 1974), we are grateful to Frank Brady (New York, NY, USA) for a copy of Fischer’s legal complaint (‘Demand for Jury Trial’, addressed to the United States District Court for the Central District of California). It was filed in 1975 against 27 parties, including Brad Darrach, Time Inc., Stein and Day, the United States Chess Federation, Burt Hochberg, Edmund Edmondson, Frank Skoff, Martin Morrison and Leroy Dubeck.

The ‘Plaintiff in pro ter’ was recorded as ‘Robert James Fischer, 300 Mockingbird Lane, South Pasadena, California. Tel: 795 5181’. He demanded a jury trial for his ‘complaint for defamation, invasion of privacy and interference with contractual relations’. The document, filed under 28 USC Section 1332, was 24 pages long and had two annexes (exhibits). These comprised advertisements reproduced from the United States Chess Federation’s magazine:

Chess Life & Review, January 1975, page 19

Chess Life & Review, September 1975, page 603

With much textual repetition the cause of action fell into eight sections:

- 1. (Against all the Defendants): ‘For libel.’ Fischer claimed that the advertisement for Darrach’s book in the January 1975 Chess Life & Review contained ‘statements in writing and a drawn likeness of Plaintiff which were false and malicious, and set forth with an intent to injure, disgrace and defame and humiliate the Plaintiff ... Said language and drawn likeness portrayed the Plaintiff as grotesque, immature, paranoid, filthy in his personal habits, avaricious, peculiar in his relationship with his mother, extremist and perverted and possessing a number of other undesirable traits.’

‘... All such charges, references, assertions and imputations were false, malicious and unprivileged, and were calculated to and did expose Plaintiff to hatred, contempt and ridicule, causing him to be shunned and avoided and proximately caused him to sustain severe nervous shock and strain, and to suffer great mental anguish, humiliation, shame and embarrassment.

As a direct result of the foregoing, Plaintiff has suffered general damages in the amount of $20 million US dollars.

As a further result of the foregoing, FIDE Delegates who would have voted in favor of amending the FIDE world championship rules in accordance with Plaintiff’s requests after reading the ad in Chess Life & Review lost respect for Plaintiff – did not vote in favor of Plaintiff’s amendments, and as a result Plaintiff was precluded from amending the rules for the FIDE world championship match scheduled for about June 1975 in Manila, Philippines, did not compete in said match and consequently was damaged in the amount of $4 million US dollars.

As a further result of the foregoing conduct of Defendants on or about 1 April 1975 Plaintiff was stripped of his prestigious FIDE world chess champion title and thereby damaged greatly in his reputation, property and business interests, as governments, chess organizers, individuals and corporations who would have employed Plaintiff now would not and Plaintiff has suffered damages in the amount of $16 million US dollars.’

- 2. (Against all the Defendants): ‘For invasion of privacy.’ This section of the brief stated that the Defendants were aware that Fischer had ‘conscientiously and continually attempted to live a private life, except for necessary disclosures; has cherished the privacy of his personal life; and has, indeed, gone to great lengths to avoid public scrutiny of his private affairs’. The Defendants, it was claimed, had caused Fischer to be ‘subjected to great humiliation, indignity’, and he had ‘suffered great mental pain all to his damage in the sum of $20 million US dollars’.

- 3. (Against the USCF, E. Edmondson and B. Hochberg): ‘For interference with contractual relations.’ The legal text stated that during the approximate period from June 1971 to September 1972 Fischer and Darrach (as well as Time Inc.) had ‘entered into a series of agreements which provided, among other things, that Defendant, Brad Darrach, could not write any book containing any information gathered by Defendant, Brad Darrach, from Plaintiff, without Plaintiff’s permission’. The USCF was advertising and selling Darrach’s book despite being aware of those agreements. The Defendants had acted ‘with an intent to injure the Plaintiff in his contractual relationship and said acts were done maliciously and oppressively’. Fischer had ‘suffered damages in the amount of $20 million US dollars’.

- 4. (Against all the Defendants): ‘Appropriation of the right of publicity.’ Under this count, the brief claimed that the January 1975 advertisement in Chess Life & Review had employed confidential information and that the Defendants had ‘exploited Plaintiff’s services, personality and confidential history, appropriating Plaintiff’s interest in that property, and the market for Plaintiff’s proposed autobiography’. On this count, ‘Plaintiff has suffered general damages in the sum of $20 million US dollars’.

- 5. (Against all Defendants): ‘Unfair competition.’ Under this cause of action it was stated that ‘Plaintiff intended to write an autobiography, and Defendants were aware of that fact’. The brief referred to the Defendants’ ‘diversion of Plaintiff’s financial interest in his name and personality’ and asserted that ‘Plaintiff was damaged in his business and chess career’. It concluded: ‘As a result of the foregoing conduct, Plaintiff is also entitled to exemplary damages in the amount of $20 million US dollars.’

- 6. (Against all the Defendants): ‘Appropriation of right of privacy.’ Most of this section repeated claims made earlier on. It stated that as a result of the Defendants’ actions ‘Plaintiff has suffered, in his chess career and business interests, special damages in the sum of $20 million US dollars’.

- 7. (Against all Defendants): ‘Intentional infliction of emotional distress.’ As a result of the January 1975 advertisement, ‘Plaintiff suffered severe mental and emotional distress and thereby was damaged in his business and chess career and as a proximate result has suffered special damages in the amount of $20 million US dollars’.

- 8. (Against all Defendants): ‘Conspiracy.’ ‘Defendants and each of them conspired with one another and amongst themselves to defame Plaintiff by the publication of the ad This had damaged Fischer’s ‘chess career, business and property interests’ and Fischer ‘has suffered damages in the amount of million US dollars’.

In each of the eight sections the sum of $20 million US dollars was claimed against ‘each and all of the Defendants’, and there was also a request ‘for costs incurred and such other further relief as the court may deem just and proper under the circumstances’.

The fate of Fischer’s complaint is related in our above-mentioned ChessBase article.

6983. Annotating while playing (C.N. 6930)

No information has yet been found on the practice ascribed by Reinfeld to Tartakower (the annotation of games during play). Daniel King (London) asks whether such writing would have been legal in many events of Tartakower’s time.

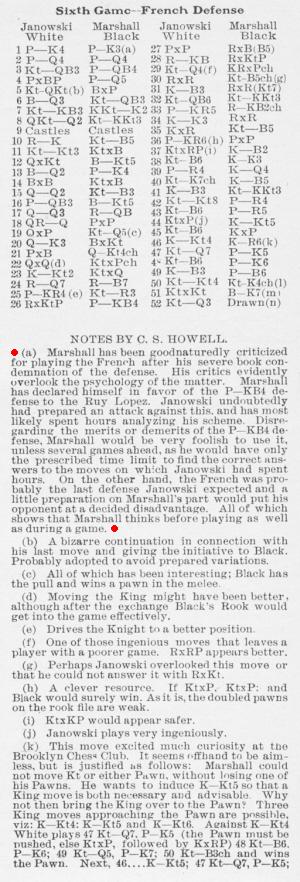

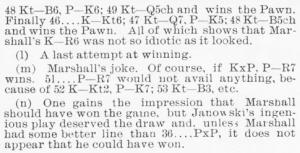

6984. Marshall and the French Defence

Further to our feature article Old Opening Assessments, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) notes a case of a leading master strongly criticizing an opening shortly before playing it in an important game. Our correspondent sends these extracts from the February 1905 American Chess Bulletin (pages 29-30 and 31 respectively):

It will be recalled that Marshall played the French Defence (by transposition) in his most famous game, against Levitzky at Breslau, 1912. We add in passing that on page 27 of the February 1935 Chess Review Arnold Denker wrote regarding the conclusion of that game:

‘This is by far the finest and most artistic queen sacrifice that I have ever seen.’

6985. Marshall, Janowsky and gambling

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) draws attention to an article about gambling in which Marshall related experiences in Monte Carlo. It appeared on page 62 of the Otago Witness of 28 June 1905, with an introductory paragraph which stated that the item was reproduced from the New Orleans Picayune. A reporter from the latter newspaper had recorded the reminiscences during Marshall’s visit to New Orleans the previous December.

Caution is required. For example, it was back in 1901 that Janowsky came first in a tournament at Monte Carlo, and his prize was 5,000 francs and an objet d’art (La Stratégie, 15 March 1901, page 88), and not 8,000 francs as stated in Marshall’s account.

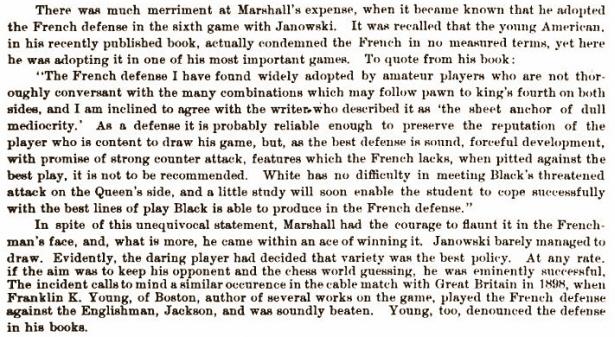

6986. St Louis, 1904

Source: American Chess Bulletin, November page 106.

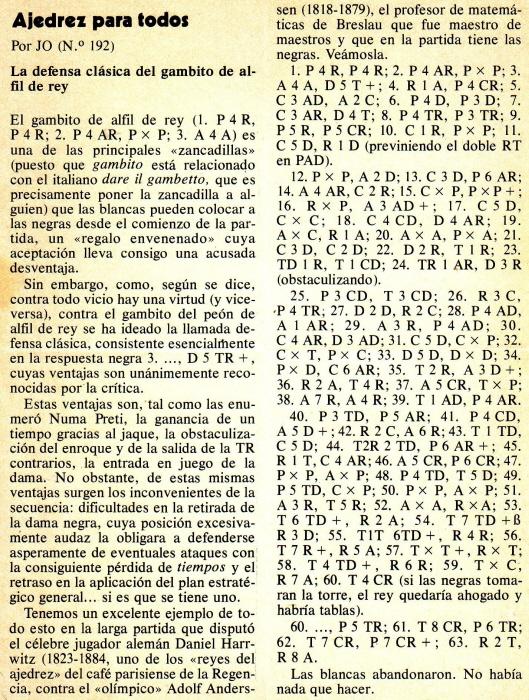

6987. Harrwitz v Anderssen?

Andrés Vicente Sanz (Valencia, Spain) sends this chess column from an unidentified publication (a cutting which he has had for over 30 years) and asks what information is available about the purported victory by Adolf Anderssen over Daniel Harrwitz:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 Qh4+ 4 Kf1 g5 5 Nc3 Bg7 6 d4 d6 7 Nf3 Qh5 8 h4 h6 9 e5 g4 10 Ne1 dxe5 11 Nd5 Kd8 12 dxe5 Bd7 13 Nd3 f3 14 Bf4 Ne7

15 Nxc7 fxg2+ 16 Kxg2 Bc6+ 17 Nd5 Nxd5 18 Nb4 Qf5 19 Bxd5 Kc8 Bxc6 bxc6 21 Nd3 Nd7 22 Qe2 Re8 23 Rae1 Rb8 24 Rhf1 Qe6 25 b3 Rb6 26 Kg3 h5 27 Qd2 Kb7 28 c4 Bf8 29 Be3 c5 30 Nf4 Qc6 31 Nd5 Nxe5 32 Nxb6 axb6 33 Qd5 Qxd5 34 cxd5 Nf3 35 Re2 Bd6+ 36 Kf2 Re5 37 Bg5 Rxd5 38 Be7 Be5 39 Rc1 f5 40 a3 f4 41 b4 Bd4+ 42 Kg2 Be3 43 Ra1 Nd4 44 Rea2 f3+ 45 Kh1 Nf5 46 Bg5 g3 47 bxc5 Bxc5 48 a4 Rd4 49 a5 Nxh4 50 axb6 Bxb6 51 Be3 Re4 52 Bxb6 Kxb6 53 Ra6+ Kc7 54 Ra7+ Kd6 55 R1a6+ Ke5 56 Re7+ Kf4 57 Rxe4+ Kxe4 58 Ra4+ Ke3 59 Rxh4 Kf2

60 Rg4 h4 61 Rg8 h3 62 Rg7 g2+ 63 Kh2 Kf1 64 White resigns.

This is, of course, a further matter requiring wariness.

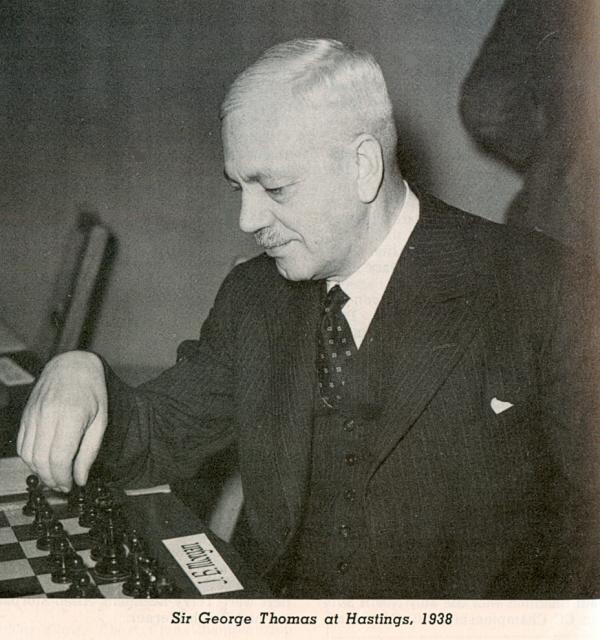

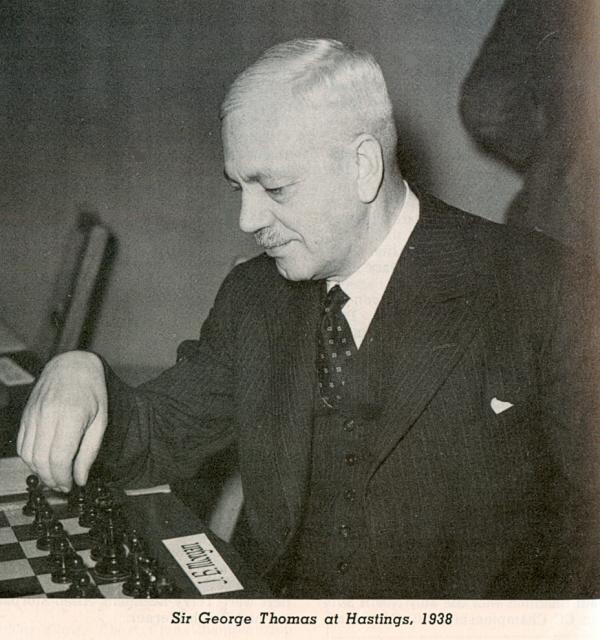

6988. Sir George Thomas

This fine photograph was published on page 716 of the November 1972 Chess Life & Review, to accompany an obituary of Sir George Thomas by T. Gordon Pollard.

Quiz question: is everything here straightforward?

6989. Sixty Years On

Another good portrait of Sir George Thomas is on page 63 of Chess: Sixty Years On with Caissa and Friends by Alan Phillips (Yorklyn, 2003). The book is exceptionally well illustrated, and we note this comment on page 74 under a photograph of Mikhail Tal:

‘In so far as “intelligence” shone forth from a human face, it shone from his.’

6990. Annotating while playing (C.N.s 6930 & 6983)

From Leonard Barden (London):

‘I witnessed Tartakower making notes during at least one game, at one or more of the Southsea tournaments of 1949, 1950 and 1951, where we both participated. His game against Ravn at Southsea, 1951, which is in his Best Games collection, sticks in my mind.

On one occasion I was curious enough to creep up behind him to see exactly what he was doing. There was a dense sheet of variations and quite small writing, and I think he had some difficulty in reading his own material, pushing his spectacles back on his forehead, screwing up his eyes, and peering closely. I feel fairly sure that nobody objected. He was a legend, and the rules on consulting written material during play were more relaxed then than now.’

6991. Fischer v Bolbochán

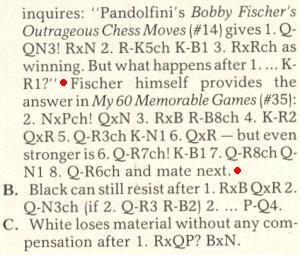

We continue to add to Fischer’s Fury various pre-Nunn/Burgess attempts to correct Fischer’s analysis in the game against Bolbochán.

This position was given on page 39 of the August 1990 Chess Life, in Larry Evans’ ‘What’s the best move?’ feature. The solution (page 58):

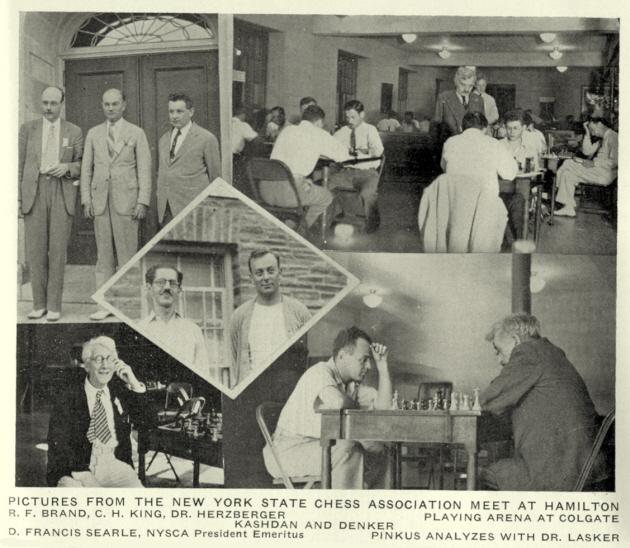

6992. New York State Championship

Source: Chess Review, October 1939, page 207.

6993. Harrwitz game (C.N. 6987)

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) reports that the game is on pages 193-194 of Harrwitz’s Lehrbuch des Schachspiels (Berlin, 1862). The heading is ‘Manchester, 1857’ and, contrary to the claim in the Spanish cutting, Harrwitz was named as Black. In addition to noting the Harrwitz book, Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) mentions that the game was published on pages 102-104 of Professor Adolph Anderssen der langjährige Vorkämpfer deutscher Schachmeisterschaft by Ludwig Bachmann (Ansbach, 1914). That work too stated that Anderssen had the white pieces.

Looking further, we have traced the game on pages 142-144 of the May 1858 Chess Monthly. This provides confirmation that Harrwitz was indeed the winner, as Black. The closing note reads:

‘This game was the last of a match played during the Manchester Meeting. Mr Harrwitz says:

“After having lost the game in the tournament to Mr Anderssen I desired my revenge, and although it was not laid down in the Progamme a short match was arranged between us to be decided by the first winner of three games. I had the good fortune to win the three in succession and – an unheard-of thing in England – they were all played at a sitting.”

These games, we believe, have been given in none of the English or German accounts of the meeting. We are indebted for the notes to the distinguished second player.’

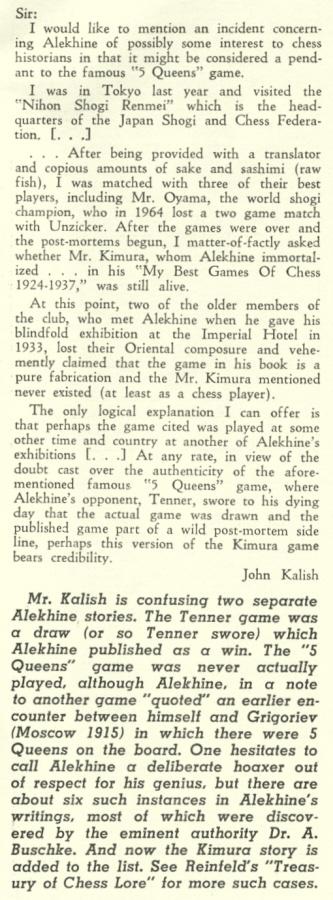

6994. Alekhine v Kimura, Tokyo, 1933

A familiar blindfold brilliancy:

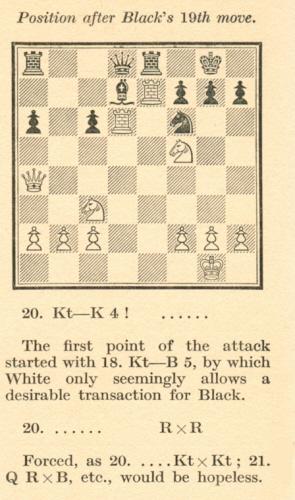

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Bxc6 bxc6 5 d4 exd4 6 Qxd4 d6 7 O-O Be6 8 Nc3 Nf6 9 Bg5 Be7 10 Qa4 Bd7 11 Rad1 O-O 12 e5 Ne8 13 Bxe7 Qxe7 14 exd6 cxd6 15 Rfe1 Qd8 16 Nd4 Qc7 17 Re7 Nf6 18 Nf5 Qd8 19 Rxd6 Re8

20 Ne4 Rxe7 21 Nxf6+ Kh8 22 Nxe7 Qxe7 23 Qe4 Qxe4 24 Nxe4 Be6 25 b3 g6 26 Nc5 Bf5 27 Rxc6 Re8 28 f3 Re2 29 Rxa6 Rxc2 30 Ne4 Be6 31 h4 Kg7 32 Kh2 Kh6 33 Kg3 Bd7 34 a4 f5 35 Ng5 Rc3 36 Ra7 Rd3 37 a5 Kh5 38 Nxh7 Resigns.

This game (Alekhine v Kimura, Tokyo, 20 January 1933) appeared in the world champion’s second Best Games volume, and the circumstances were discussed at length on pages 442-443 of the Alekhine book by L. Skinner and R. Verhoeven. The co-authors noted that although the game was widely published at the time, with Kimura listed as one of the opponents in Alekhine’s exhibition, suspicions had been expressed as to the game’s authenticity. They mentioned the following letter from John Kalish on page 273 of the July 1968 Chess Life:

Richard Sams (Tokyo) informs us that an article by Yoshio Kimura entitled ‘Thoughts on Chess’ was published on pages 190-193 of the magazine Bungei Shunju, April 1933. Below is the complete text, in our correspondent’s translation from the Japanese:

‘About a decade has passed since I first took an interest in Western shogi (chess) and decided that I would like to study it. At that time, there was a chess club at the back of the Imperial Hotel and there I first learned how to play chess under the tutelage of an Englishman, Mr Havilland, who was apparently once an amateur chess champion. At first I learned only the basics, and for a while I had no opponents or opportunities to play. Fortunately, however, through the support and guidance of Dr Ishida of the Riken Group and Professor Mitamura of the Imperial University of Tokyo, I was able to acquire useful knowledge of chess openings and strategies. Upon inquiring about the most notable chess matches, I was surprised to learn the extent to which chess has gained international popularity as the ultimate intellectual contest. This aroused my interest further, giving me an even greater desire to study the game more deeply.

From that time on, Professor Mitamura helped me with my studies by providing me not only with well-known books on chess but also with specialist publications on matches from Europe and America. I thereby acquired a little knowledge of the exploits of leading players in the West and the most recent matches taking place around the world. This greatly increased my enthusiasm, and I even came to embrace the conceit and ambition that, if I could make a serious study of chess as I had of shogi, I might even be able to compete for the world championship.

One reason I came to think this is that, because chess is quite similar to shogi in many respects from strategy to the deployment of pieces and tactical methods, I would be able to adapt to its fundamental reasoning. Furthermore, the fact that, unlike in shogi, the pieces are no longer in play once they have been captured made chess seem quite simple (from the viewpoint of a professional shogi player). Therefore, armed with the profound technical skills characteristic of shogi, I might even be able to compete for the world championship in chess. Until quite recently, I had confidently held this conviction.

Seven years ago, the Tokyo Chess Club was established with the late Dr Fukada as President and Dr Masataka Ota as Vice-President. The inaugural meeting took place at the Tokyo Kaikan. Subsequent club meetings were held twice a month in a room in the Imperial Hotel. The original founding members were Dr Fukada, Viscount Masatoshi Okouchi, Dr Ota, Count Akira Watanabe, Baron Tatsukichi Nagakoshi, Mr Jozo Ikoma, Dr Yoshio Ishida, Dr Masaharu Nishikawa and Professor Atsushiro Mitamura, together with the professional shogi players Osaki 8-dan, Kon 8-dan and me.

The club met twice a month and, with the attendance of four or five chess enthusiasts from overseas, it flourished for a while. It was very enjoyable to do battle with foreigners over the chess board, but after Dr Ishida, Professor Mitamura and I decisively defeated three foreign opponents, including the strong player Mr Havilland, we found ourselves without any suitable rivals and had no choice but to play each other. As a result, the club’s activities gradually fell into abeyance.

At the time, I was quite intoxicated with feelings of superiority, having beaten foreigners at chess, but I was also concerned because I did not really know my true strength (in the eyes of a professional chessplayer). Then I learned that the world chess champion Alekhine, who was en route to a match in Shanghai, was planning to visit Japan on 16 January for just one week. I had already heard of Mr Alekhine about seven or eight years previously and viewed this as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to determine my chess ability. Professor Mitamura telephoned Mr Alekhine to arrange a meeting, and we went to his hotel the following day (17 January). Somehow we missed him at the hotel and had to wait for a while. As usual, Professor Mitamura was well prepared. He showed me a photograph of Mr Alekhine at the front of a book which the world champion had written on a recent international tournament, so that we could stop him if we saw him leaving the hotel. Shortly afterwards Mr Alekhine appeared, and I was introduced to him as a professional shogi player. He is a splendid-looking gentleman, well built and easily six feet tall. He was more approachable than I imagined and seemed to possess a strong artistic sensibility. When Professor Mitamura showed me Mr Alekhine’s book, explaining how rich it was in content as a practical guide for students of chess, Mr Alekhine’s face seemed to light up, and he at once became more relaxed and familiar. He said he had heard that different forms of chess were played in Japan, China and India, and that, since Japanese chess was particularly sophisticated, it should be studied. He had therefore decided to come to Japan to learn more about it. As professional shogi players, we had considered the possibility of promoting shogi overseas, but we thought that it might be hard to understand for Westerners, who find chess a sufficiently difficult game. We also could not think of any suitable way of explaining the excellence of shogi and teaching it. However, considering that the most effective method would be for a respected professional chessplayer such as Mr Alekhine to introduce shogi to the world, I decided to take it upon myself to teach him the game.

Through the good offices of Dr Ishida we then made arrangements for a gathering of Japanese and foreign chess enthusiasts to honor the world champion. The Japan Shogi Federation undertook to organize a party and provided various assistance in making the preparations. We were particularly grateful to Count Yanagisawa for his help and to Mayor Nagata, who went so far as to arrange a welcome reception at the Japan Club, where Mr Alekhine was presented with a souvenir.

When the preparations had been made, what we desired most of all was for Mr Alekhine to display his skills as the world chess champion. He agreed to this, proposing to play a blindfold simultaneous display against all of us. I thought that, even for the world champion, it would be difficult to play simultaneously against 14 opponents of different strengths, to keep the positions in his mind and remember the moves of all the games without making any oversights, and surely impossible to win all of them, whatever the difference in strength between him and his opponents. However, Professor Mitamura pointed out that, since Mr Alekhine was the world record holder in blindfold simultaneous chess and had played blindfold against 26 opponents in New York in 1926 and 28 opponents in Paris in 1928, he should have no difficulty with just 14 opponents.

Here I think a brief outline of how Mr Alekhine has succeeded in reaching the pinnacle of world chess will provide insights into his serious attitude to chess and his character, which has particularly impressed me. Mr Alekhine is currently a French citizen living in Paris, and plays mainly against Russian opponents. A Polish-Russian, he is 42 years old according to the Japanese age-counting system. In 1914, while he was taking part in an international tournament in Mannheim, Germany, the Great European War broke out and he was for some reason taken prisoner. After being interned for almost two months, he was released and returned to Russia. He was drafted into the army and fought bravely, but having earlier graduated from law school, he was soon appointed to serve in the foreign ministry, mainly undertaking work related to criminal law. After he left this post, the Russian Revolution occurred and, under the suspicion of the Soviet Government, he was again imprisoned for a while, but succeeded in escaping to Paris five years later. Clearly he experienced great vicissitudes of fortune up to the time he became a French citizen in 1921. In 1924, he displayed his strength at the New York international chess tournament, where he came third below Lasker and Capablanca, who took first and second places respectively. In the spring of 1927, he again took part in an international tournament in New York, coming second behind the world champion Capablanca, thereby obtaining the right to challenge the latter to a match. This took place in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in the autumn of 1927. After a two-month long battle, Alekhine won an overwhelming victory of 6-3 and was crowned world champion. In 1931, he was challenged by Bogoljubow, another Russian who had become a German citizen, brilliantly retaining his world championship title with a score of 6-3. [It will be noted that Kimura’s biographical information about Alekhine contains a number of factual errors.]

Alekhine’s record since winning the world championship has been outstanding. He has not just won first prize in tournaments all over the world but has also won his games in fine style. His attitude to chess is deeply serious and he shows no sign at all of underestimating his opponent. Although I am considered a strong chessplayer in Japan, I must seem to him a mere novice. Nevertheless, when he sat down to play me, he showed no sign of relaxing his attention, and at moments where an unexpectedly interesting position arose he studied the position afterwards and explained it with the attitude of a researcher. His kindness and obvious passion for the game made this encounter a very pleasant experience for me.

Alexander Alekhine

According to Professor Mitamura, the world champion is well liked all over the world and praised for his character considerably more than other leading chessplayers. This reputation speaks volumes about his nature and breeding. Mr Alekhine says that for him chess is a way of refining the intellect and should transcend materialism, a statement which reflects his spiritual nature. He gives the impression of being very sensitive and straightforward, with no interest in flattery or deferring to conventional wisdom. I think that this is because, as well as being courteous and modest, he is above all an artist. His attitude calls to mind the Western tradition of chivalry, which is similar to the spirit of Bushido in Japan.

We did not have much time to teach shogi to Mr Alekhine but succeeded in outlining the rules, how the pieces move, and some basic opening strategies. He is a very quick learner. When I played a game with Professor Mitamura to show him an example of actual play, he indicated a move which he had not expected and asked about the best move in that position. This no doubt comes from his knowledge of chess, which gives him a confidence one rarely sees in people when they first learn shogi. I am sure that he will be able to introduce the game in the West based on what he has learned, and that this will make a great contribution to the future development of shogi.

Representing the Japan Shogi Federation at the welcome party on 20 January at the Imperial Hotel were the Meijin (shogi champion) Sekine, Doi 8-dan, Kon 8-dan, Hanada 8-dan, and Mr Nakajima. The party was also attended by chess lovers from both Japan and overseas who wanted to witness the amazing feat which the world champion was about to perform, and this made for a very congenial and pleasant atmosphere. On behalf of the Japan Shogi Federation, Mr Nakajima made a welcome speech in fluent English, stating that shogi and chess came from the same roots and expressing the hope that we could cooperate for their mutual development. Mr Alekhine said that, while chess and shogi may constitute only a small part of our respective cultures, they can play a significant role in promoting friendship among the peoples of the world. He promised to introduce shogi in the West with this aim in mind.

Now it was time for the final event in the program, the blindfold simultaneous chess display. In addition to Dr Ishida and Professor Mitamura, Kon 8-dan and I participated as professional shogi players studying chess. Also taking part were the foreign chess enthusiasts Clausnitze, Alexander, Mosler, Baumfeld, Kramer and Gotzscheke.

All the games in the blindfold display were played without odds. Thinking that I would have no chance of winning if I activated my pieces too early in the opening, I adopted a strategy of defending and waiting for my opponent to make a mistake. In the end, all 14 of us lost without much of a struggle. Considering my initial hopes, I felt quite ashamed of my inability to put up serious resistance, but I was also deeply impressed by the world champion’s extraordinary display of chess skill. On the way home, Kon 8-dan said that he considered Mr Alekhine’s feat almost inhuman.

Mr Alekhine told Professor Mitamura later that, in view of my experience in shogi, I could become a strong chessplayer if I studied intensively for six months. He says that he would like to visit Japan again next year, so it seems that he also has desires to study shogi. I showed him all the hospitality I could during the remainder of his stay in Tokyo until his departure for Shanghai on the morning of 22 January.

Finally, I should also like to express my thanks to the foreigners who took part in the simultaneous display and all those who attended the event.’

From page 276 of My Best Games of Chess 1924-1937 by A. Alekhine (London, 1939)

On the analytical front, we made a brief comment about Alekhine v Kimura on page 317 of the July 1985 BCM, pointing out that in Chess Life, January pages 22-23, Jan Frise of Sweden had shown that Alekhine’s note to 20...Rxe7 was faulty, because after 20...Nxe4 21 Rdxd7 ...

... Black can play 21...Qxd7, with the continuation 22 Rxd7 Nc3 (threatening 23...Re1 mate and forcing White to take perpetual check with 23 Nh6+).

Frise’s discovery (we are aware of no reference to

21...Qxd7 before 1980) was overlooked on page 80 of Alekhine

in Europe and Asia by J. Donaldson, N. Minev and Y.

Seirawan (Seattle, 1993), which misascribed the line to

G.B. Lewis (who had mentioned it much later than Frise,

i.e. in 1985). For further remarks on the Alekhine v

Kimura position, by Larry Evans, see Chess Life,

March 1989 (page 58) and February 2002 (page 32).

On page 361 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves (an item reproduced in The Games of Alekhine) we observed regarding Alexander Alekhine’s Best Games by A. Alekhine (London, 1996):

‘Many analytical emendations pointed out over the years by third parties are ignored; for instance, Alekhine’s note to Black’s 20th move in his game against Kimura at Tokyo, 1933 has been widely censured, but the Batsford book offers no comment.’

Incidentally, it would appear that Alekhine made a small factual error in his Best Games book, giving the number of opponents in the blindfold display as 15, instead of 14.

Another master who visited Japan in the 1930s was Lajos Steiner. His report, ‘A Chessplayer Turns Explorer’ on page 37-38 of the February 1937 Chess Review, included this paragraph:

‘Among the Japanese themselves, there are, as far as I know, only two players with real insight into the game. One is Professor Mitamura, a great pathologist and a member of the Imperial University of Tokyo. He is a man of keen intelligence, who speaks English and German well. Kimura, the greatest living shogi player, is the other.’

An article on shogi by Larry Kaufman on pages 28-33 of the September 1983 Chess Life mentioned Kimura Yoshio and gave a photograph of Korchnoi receiving an explanation of shogi from Aono Teruichi in London in 1980.

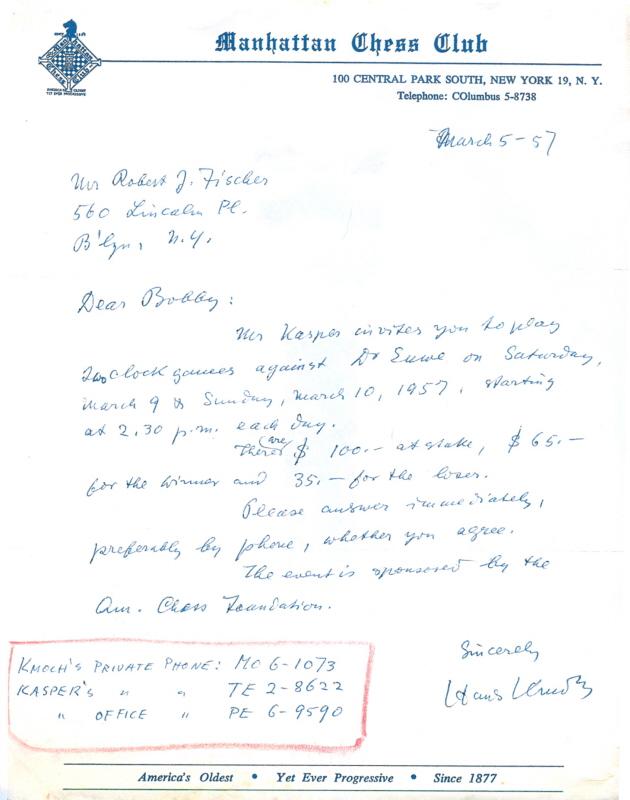

6995. Euwe v Fischer, 1957

Courtesy of Frank Brady (New York, NY, USA) we reproduce a letter dated 5 March 1957 in which Hans Kmoch forwarded an invitation to Fischer to play two games against Euwe:

Fischer agreed, but it is only recently that the full score of the second game, a draw, has become known, thanks to Dr Brady’s researches.

A photograph showing play in the first game was on the front cover of the April 1957 issue of Chess Review:

6996. Showalter v Lipschütz: a match in 1890?

From Larry Crawford (Milford, CT, USA):

‘G.H. Mackenzie was considered the US champion “by acclaim”, as was Morphy before him. Mackenzie won the second (Cleveland, 1871), third (Chicago, 1874), and fifth (New York, 1880) American Chess Congresses but was too ill to play in the sixth Congress (New York, 1889). S. Lipschütz was the US player who finished highest behind the five foreign masters at New York. On the assumption that Mackenzie had retired owing to poor health, a claim was made to consider Lipschütz the new US champion. In February 1890 Showalter finished ahead of Lipschütz at the third Congress of the US Chess Association, held in St Louis. Soltis and McCormick wrote on page 29 of the second edition of The United States Chess Championship, 1845-1996 (Jefferson, 1997):

“The gentleman farmer from Minerva, Kentucky [Showalter], then [after St Louis] crowned his success in a short match with Lipschütz and it was on the basis of this that he would later say he was US champion.”

The book gave one game played between Showalter and Lipschütz (“Match, Louisville 1890”).

There are hints here and there about an 1890 Showalter-Lipschütz match:

- “About this time he [Showalter] won nine straight games of Lipschütz (including the two games in the St Louis Tourney), at Cincinnati, Georgetown [KY], Lexington and Indianapolis, winning a purse of $50 offered by the Indianapolis Club.” (Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly, August 1894, page 249).

- “Beaten by Showalter at St Louis and Indianapolis, he [Lipschütz] subsequently defeated him [Showalter] in a match in New York by seven to one and seven draws.” (Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly, September 1894, page 250).

- “Played at Indianapolis, in an unfinished match between Messrs. J.W. Showalter of Georgetown, Ky and S. Lipschütz of New York, the first and third prize-winners in the recent US Association Tourney.” (BCM, May 1890, page 208). In the BCM one game was given (not the same game as in Soltis and McCormick’s book).

- “Wie verlautet, werden die Herren Showalter und Lipschütz einen Match mit Einsatz von 300$ in Louisville demnächst spielen. (Louisville ist unterdessen durch einen Orkan verwüstet worden. D. Red.)” (Deutsche Schachzeitung, April 1890, page 127). That tornado hit Louisville on March and is unlikely to be relevant to the issue at hand, unless the match was to be held after Lipschütz finished his match with Delmar.

- “Showalter and Lipschütz will go together to Louisville to play a match of seven games for a prize.” (New York Sun, 12 February 1890, page 4).

I found it easier to track Lipschütz’s movements in the New York Sun during early 1890 than those of Showalter. Lipschütz was back in the city in time to play in the State tournament on 22 February. He also had an ongoing match with Eugene Delmar. They played two games in January prior to Lipschütz leaving for St Louis, and they resumed the match on 4 March. They customarily played games on Tuesdays and Saturdays, but with adjournments there were some variations in that schedule. I see games listed on 4, 8, 11, 18 and 29 March and 5, 12, and 19 April, with games seven and eight probably played on 22 and 25 March respectively.

Showalter’s match with Judd began on 19 May 1890. Contemporary newspapers called it a championship match. Here are a few examples:

- “The first game in the match between Max Judd and J.W. Showalter at St Louis for the championship of the United States was played on Monday night.” (New York Sun, 23 May 1890, page 4).

- “Max Judd, of St Louis, and James [sic] Showalter, of Kentucky, opened their series of chess contests at the rooms of the chess club in St Louis last night for the American championship and a purse of $500.” (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 19 May 1890, page 4).

- “... the chess contest between O. [sic] W. Showalter, the champion of the United States, and Max Judd of St Louis for $250 and the championship ...” (New York Evening Post, 21 May 1890, page 5).

It seems that a Showalter-Lipschütz match would be the basis for Showalter’s original claim to the US championship title, and for such a match to occur after the St Louis tournament and before the Judd match it would need to have taken place between 11 and 22 February 1890 or possibly between 19 April and 19 May 1890.

Further clouding the waters, in a column at the Chess Café Hanon Russell quoted extensively from a letter by Walter Penn Shipley published in Lasker’s Chess Magazine, November 1904 (see pages 13-15):

“After the death of Captain Mackenzie, S. Lipschütz, who had won a number of matches and tournaments, was recognized both in the East and in the West as the American champion. That title was given to him by all the clubs and in the various chess columns published throughout this country and many of those abroad. I never heard the same in any way disputed. In 1891, Showalter challenged Lipschütz for a match for the American championship and a stake of $750 a side.”

When Max Judd was planning the 1904 St Louis American Chess Congress he wanted to call the winner “US champion”. Judd’s position was that while Pillsbury was the strongest player of his day, he never played anyone who held the title of US champion and therefore did not hold the title himself. Pillsbury objected, and both he and Judd appealed to Shipley as an arbiter. Shipley detailed the lineage of the US championship to show that Showalter was, in fact, US champion when Pillsbury defeated him in 1897. The first Showalter v Lipschütz match which Shipley mentioned is the one which Lipschütz won in 1892 (the challenge was issued in 1891, but the match was played in 1892). Shipley was well informed on US chess, knew many top players, and served as the stakeholder for the 1896 Showalter v Kemény match. Was Shipley’s omission of an 1890 Showalter v Lipschütz match an indication that no match took place or that a match began but was not completed?’

6997. Jeremy Gaige (1927-2011)

Marking the recent death of Jeremy Gaige, we reproduce C.N. 1491, which concerned his book Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987):

About 14,000 chess personalities past and present are featured in this awe-inspiring book. From Erkki Aaltio to Adolf Zytogorski, each entry aims to give the date and place of birth and, where appropriate, death. A selection of newspaper, magazine and book sources is cited, as are FIDE titles, Elo historical ratings, etc. To take one entry at random:

‘Bogoljubow, Efim Dimitrijewitsch

born: 14 April 1889 Stanislavitsk/Kiev, USSR

died: 18 June 1952 Triberg, Federal Republic of Germany

GM 1951

Elo Historical Rating: 2610

American Chess Bulletin, 1952, page 72

British Chess Magazine, 1952, pages 253-254

Caissa, 1952, pages 133-134

Chess Pie No. l, 1922, pages 8-10

Chess Review, 1952, page 200

Chess Career of E.D. Bogoljubow by Jack Spence

Deutsche Schachzeitung, 1952, pages 224-225

Deutsche Schachblätter, 1952, pages 115-116

Grossmeister Bogoljubow by Alfred Brinckmann

Teplitz-Schönau 1922, pages 567-568.’His date of birth is marked to indicate that it has been converted to the Gregorian Calendar (New Style).

As an indication of the vast scope of the book: how many chessplayers whose surnames begin with Z could the average enthusiast recite? Gaige lists over 250.

The value of such data is enormous, and the book is particularly valuable for the details it provides on relatively minor figures. If the reader wishes to know the exact date and place of death of Henry Grob (of 1 g4 fame), it is unlikely that he will find the correct information anywhere other than in Chess Personalia (3 July at Zollikon, Switzerland, the source of this information being Stadtarchiv Zurich). In countless cases the entrants themselves, or their next of kin, have been contacted for authoritative biographical information. For old players an astonishing array of journals is quoted; for Sarratt we are referred to page of the Bell’s Weekly Messenger and the 14 November 1819 issue of the London Observer.

Chess Personalia is a brilliant achievement. It will prove indispensable not just to historians and journalists but also to clubs, federations, libraries and players, composers, etc. There are precious few books which we would recommend to our readers as indispensable, but Chess Personalia is definitely one of them.

That Jeremy Gaige finds the time and energy for so much high-quality research is almost miraculous; he stands supreme as chess’s greatest ever archivist.

A more detailed evaluation of Jeremy Gaige’s chess work is provided in an article contributed by us on pages 58-60 of the 8/1987 New in Chess. On 12 March 2011 we placed on record at ChessBase Gaige’s ‘self-obituary’, which he sent us for safe keeping in 1988.

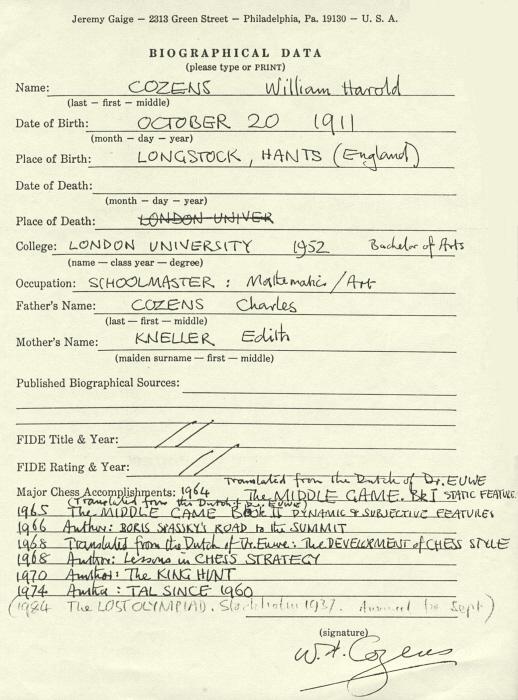

6998. W.H. Cozens

Jeremy Gaige gathered much data with a biographical form circulated to chess personalia. By way of example, below is the sheet completed by W.H. Cozens:

The information about his parents has taken us to the remarkable Cozensweb site, which gives many further details.

See also C.N. 3183 in Chess Jottings.

6999. Marshall, Janowsky and gambling (C.N. 6985)

Russell Miller (Vancouver, WA, USA) has

found the original

article, on page 23 of the Times-Picayune

(New Orleans), 4 December 1904.

7000. Sir George Thomas (C.N. 6988)

It is uncertain whether this photograph was taken at Hastings, 1937-38 or 1938-39. Nor is the significance of the name label (‘J.B. Morgan’?) apparent. Above all, of course, the board is incorrectly set (rotated by 90 degrees).

7001. Zugzwang in a queen ending

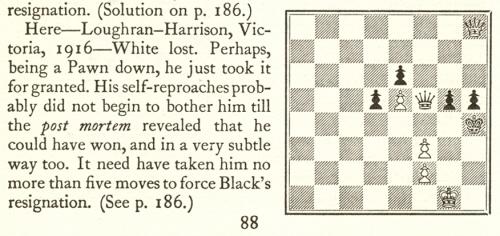

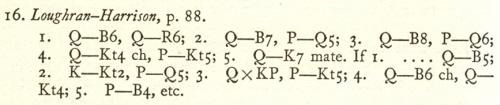

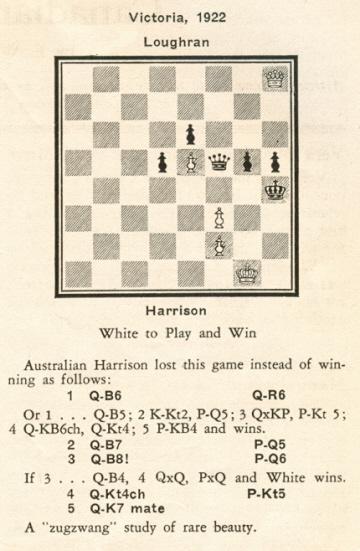

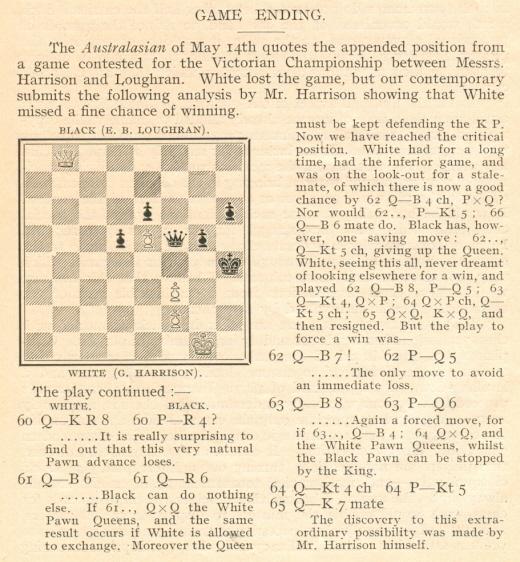

From page 88 of The Pleasures of Chess by Assiac (New York, 1952):

The solution on page 186:

Tracing the position backwards, we note, firstly, the following on page 42 of Chess Review, February 1935, in an article ‘Mistakes of the Masters’ by Lester W. Brand:

It will be seen that the players’ names are inverted compared to Assiac’s version, with a different date (1922 instead of 1916).

A more detailed account of the ending was given on page 262 of the August 1916 BCM:

A crosstable of the championship of Victoria, a

double-round tournament played in Melbourne from 19 April

to 21 July 1916, was presented in volume one of The

Records of Australian Chess by John van Manen

(Modbury Heights, 1986). Compiled from reports in the Australasian,

April-July 1916, the crosstable shows that Loughran scored

a win and a draw against Harrison.

Can further information be found about the above Harrison v Loughran game?

7002. Who?

Two leading players supposedly depicted in sketches in a recent chess book:

7003. Blind pigs (C.N.s 3494, 3525, 5160 & 6108)

From page 215 of The Golden Treasury of Chess by Francis J. Wellmuth (Philadelphia, 1943):

7004. Reshevsky at West Point

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) draws attention to an article ‘An Adult Views All These Child Prodigies With Alarm’ by Edwin H. Blanchard in the New York Evening Post, 3 December 1920. Below is the paragraph regarding chess:

‘This invasion of the innocents is not confined to literature. Take Samuel Rzesce – that is, Samuel Rcezcs – well, you know whom I mean – the Polish boy wizard, eight years old or so, who comes over here and beats the pick of West Point playing chess. What’s to be made from that? What’s the sense of spending a lot of money training army officers for four years if a child eight years old can come over from Poland and beat them all at once? What’s to prevent Samuel, the boy wonder, from going back to Poland and getting four or five of his little chums and coming back here and capturing the entire coast defences? The thing is internationally serious.’

7005. Spassky on Petrosian and Korchnoi

From an article by Boris Spassky ‘The Petrosian-Korchnoi Match: Petrosian Was True to Himself’ on pages 625-627 of the November 1971 Chess Life & Review:

‘The most outstanding feature in the style of ex-world champion Tigran Petrosian is his desire to keep his opponent at his own distance. This can be seen in every game as well as in the overall plan of the match. This is purely his own individual style, his chess character.

Victor Korchnoi may be described as a searching chessplayer. To me, he seems more a destroyer of the other player’s plans and positions rather than a creator. His strength is most evident in counter-attacks. He is known for his flexible playing style and colossal energy and working capacity during a game ...

Korchnoi is also a fighter with stubbornness that anyone could envy. He is tenacious in defense and can become quite “angry” – in the sports sense of that word. When he tackles a problem that comes up over the board, I believe the Leningrad grandmaster has a tendency not to trust his intuition; rather, he relies more on hard, cold calculations. His ability to figure out various continuations far in advance helps him in the endgame.

By his style, Korchnoi is more a tournament player than a match player. Sometimes, when he gets carried away by his ideas and original plans he does not reckon with the more prosaic aspects of chess. One of his shortcomings in his “ability” to get into time-trouble.

Comparing the styles of the two players, it must be said that Petrosian is a tough opponent for Korchnoi. After all, during the course of the struggle Korchnoi has to be able to discover his opponent’s plan in order to begin “destroying” it. But Petrosian’s style is often based on waiting, maneuvering, “semi-tones”. That is why the temperamental Korchnoi often had to shoot at blind targets.’

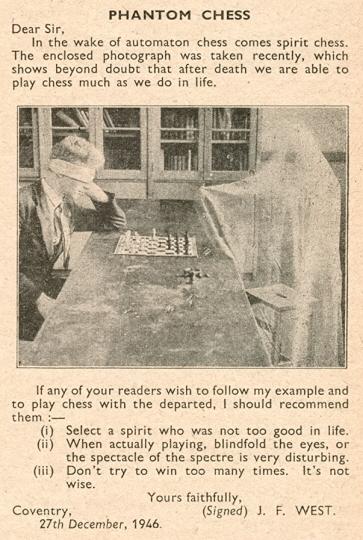

7006. Ghosts

CHESS, February 1947, page 145

CHESS, February 1948, page 129.

7007. Zugzwang in a queen ending (C.N. 7001)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) comments that in various editions of Kurt Richter’s books Schachmatt and Kombinationen the game ending was given as either Harrison v Longhran or Longhran v Harrison (and not with the correct spelling Loughran).

Our correspondent adds that he has the conclusion of the game in a database with a specific date (26 April 1916). What is the source of that information?

7008. Zukertort v Adair

‘It is our conviction that no recorded victory over the great champion approaches this game in beauty of combination.’

That remark comes from the Elizabeth Herald (New

Jersey), in a set of notes reproduced on page 309 of the

Chess Player’s Chronicle, 27 February 1884.

Chicago, 10 January 1884

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 exf4 4 Nf3 g5 5 h4 g4 6 Ng5 h6 7

Nxf7 Kxf7 8 d4 d5 9 exd5 Nce7 10 Bc4 Kg7 11 O-O f3 12

gxf3 g3 13 Bf4 Nf5 14 Be5+ Nf6 15 Ne4 Be7 16 Qd2 Rf8 17

Qf4 Kh7 18 Bd3 Nxd5 19 Qg4

19...Nde3 20 Qh5 Bxh4 21 Rfe1 Nd5 22 Re2 Nb4 23 Bc4 Nxd4

24 Rd2 Nxf3+ 25 Qxf3 Rxf3 26 Rxd8 Bxd8 27 White resigns.

Page 290 of A Chess Omnibus mentioned a subsequent report that a correspondent of the New Orleans Times-Democrat had noted a forced mate in three with 24 Bg8+. Does any reader have access to the relevant issue of the newspaper?

Adair scored another win over Zukertort the same day, in 22 moves. See, for instance, page 93 of the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 15 March 1884, page 173 of the May 1884 BCM and page 81 of The Golden Treasury of Chess by Francis J. Wellmuth (Philadelphia, 1943). The Wellmuth book misdated the game 10 January 1886.

The circumstances of the encounters were recorded on page 167 of the February 1884 Chess Monthly:

‘On Thursday, 10 January, the champion met and fought Mr James Morgan in a game lasting five hours, which resulted in a draw. In the evening Dr Zukertort won two games from Mr Hosmer. He was then beaten two games out of four by Mr John D. Adair, a well-known lawyer of Chicago and secretary of the local chess club. Both games scored by Mr Adair were brilliant specimens of the Allgaier, in which he is remarkably strong. On Monday evening Mr Adair again succeeded in winning a game, making the score between them: Zukertort 6, Adair 3. This is believed to be the best record made against the distinguished visitor thus far by any player in America.’

Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia has an entry for Colonel John Dunlap Adair (1843-1903). We note too an historical society’s webpage which has a photograph of Adair, provides a summary of his military and legal careers and refers to his strength as a chessplayer.

7009. Who? (C.N.

7002)

Boris Spassky and Viswanathan Anand

The sketches come from Key Chess Puzzles by Robert J. Richey (Bloomington, 2011). A further identification challenge:

See C.N. 4399 for another resemblance-free sketch of the same master.

For an example of the prose content of Mr Richey’s book, we go no further than pages 1-2, with the procedure for the ‘Game Startup’ explained in all its intricacy:

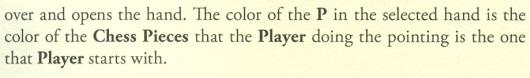

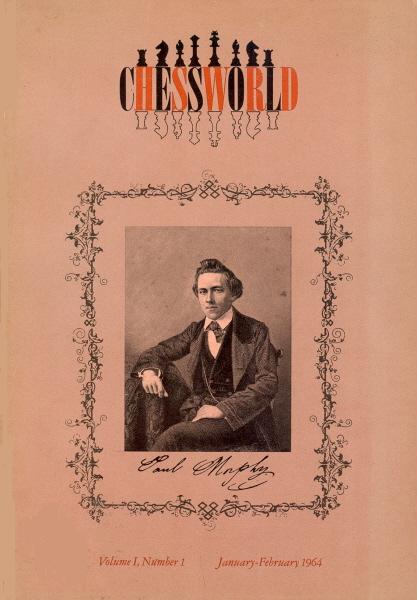

7010. Chessworld

Only three issues of the exceptional magazine Chessworld were published (in the first half of 1964), but there were some memorable scoops, including, in the first issue, Fischer’s ‘The Ten Greatest Masters in History’.

The magazine’s editor and publisher, Frank Brady, has generously allowed us to reproduce the complete article. It is given in ‘Fischer’s Views on Chess Masters’, where, in due course, more Fischer quotes will be added from other sources.

7011. Damiano’s Defence

Han Bükülmez (Ecublens, Switzerland) asks about a line in Damiano’s Defence which was discussed in Gary Lane’s Opening Lanes article of 2 March 2011: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 f6 3 Nxe5 fxe5 4 Qh5+ Ke7 5 Qxe5+ Kf7 6 Bc4+ d5 7 Bxd5+ Kg6 8 h4 h5

At this point Lane wrote:

‘9 Bxb7! This is the move that has sealed the fate of the Damiano Defence. White wins material and still has a terrific attack in reserve. I came up with this move some time ago thanks to the help of the computer and no doubt others have also discovered it, but as far as I know nobody has had the chance to play it at the board.’

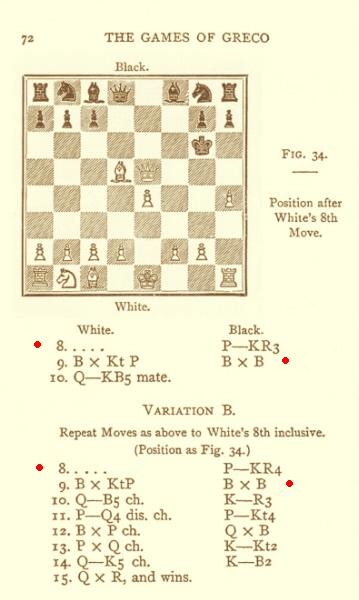

We would simply point out that 9 Bxb7 goes back to Gioacchino Greco. See, for instance, page 72 of The Games of Greco by Professor Hoffmann (London, 1900):

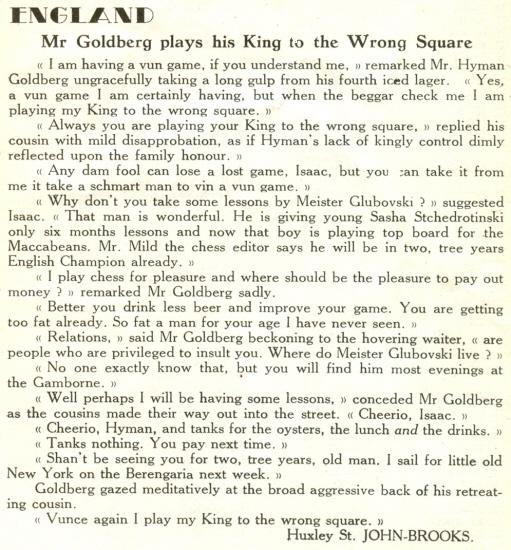

7012. Chess sketch

C.N. 3417 quoted a brief text by Huxley St John Brooks which C.J.S. Purdy described as ‘the best short humorous chess sketch ever written’. Below is another piece by the same writer, from page 291 of the Chess World, 8 April 1933:

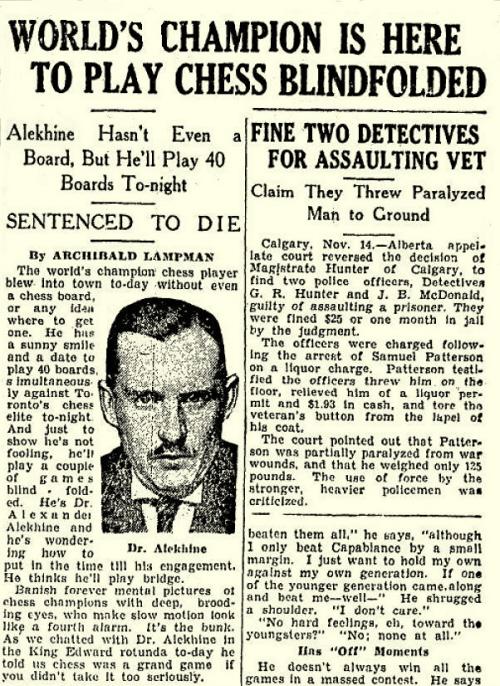

7013. Alekhine interview

Is any reader able to supply the original version of an interview with Alekhine published in the Toronto Daily Star, 14 November 1932? Currently we have only the text reproduced on pages 174-176 of the Chess World, January 1933.

7014. Gallows humour (C.N.s 6968 & 6981)

From Mark N. Taylor (Mt Berry, GA, USA):

‘The anecdote about Judge Kames’ “checkmate” comment resembles the better-known Sir Walter Scott story which is attributed to Judge Braxfield – and for good reason. I believe that the earliest published source of the story is pages 569-570 of volume one of Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott by John Gibson Lockhart. The quote below is taken from the edition published in Philadelphia in 1837:

“Scott told, among others, a story, which he was fond of telling, of his old friend the Lord Justice-Clerk Braxfield; and the commentary of his Royal Highness [the Prince Regent, the future King George IV] on hearing it amused Scott, who often mentioned it afterwards. The anecdote is this: Braxfield, whenever he went on a particular circuit, was in the habit of visiting a gentleman of good fortune in the neighbourhood of one of the assize towns, and staying at least one night, which, being both of them ardent chessplayers, they usually concluded with their favourite game. One Spring circuit the battle was not decided at daybreak, so the Justice-Clerk said, ‘Weel, Donald, I must e’en come back this gate in the harvest, and let the game lie ower for the present’; and back he came in October, but not to his old friend’s hospitable house; for that gentleman had, in the interim, been apprehended on a capital charge (of forgery), and his name stood on the Porteous Roll, or list of those who were about to be tried under his former guest’s auspices. The laird was indicted and tried accordingly, and the jury returned a verdict of guilty. Braxfield forthwith put on his cocked hat (which answers to the black cap in England), and pronounced the sentence of the law in the usual terms, ‘To be hanged by the neck until you be dead; and may the Lord have mercy upon your unhappy soul!’ Having concluded this awful formula in his most sonorous cadence, Braxfield, dismounting his formidable beaver, gave a familiar nod to his unfortunate acquaintance, and said to him, in a sort of chuckling whisper, ‘And now Donald, my man, I think I’ve checkmated you for ance’. The Regent laughed heartily at this specimen of Macqueen’s brutal humour; and ‘I’faith, Walter’, said he, ‘this old big-wig seems to have taken things as coolly as my tyrannical self.’”

Source: Scottish Men of Letters in the Eighteenth Century by Henry Grey Graham (London, 1901)

As Craig Pritchett pointed out in his article in the June 2008 CHESS, the problems with Lockhart’s account were noted by Lord Henry Cockburn on pages 117-118 of Memorials of his Time (Edinburgh, 1856):

“When Lord Kames, an indefatigable and speculative but coarse man, tried Matthew Hay, with whom he used to play at chess, for murder at Ayr in September 1780, he exclaimed, when the verdict of guilty was returned, ‘That’s checkmate to you, Matthew!’ Besides general and uncontradicted notoriety, I had this fact from Lord Hermand, who was one of the counsel at the trial, and never forgot a piece of judicial cruelty which excited his horror and anger.

Scott is said to have told this story to the Prince Regent. If he did so, he would certainly tell it accurately, because he knew the facts quite well. But in reporting what Sir Walter had said at the royal table, the Lord Chief Commissioner Adam confused the matter, and called the judge Braxfield, the crime forgery, and the circuit town Dumfries; and this inaccurate account was given by Mr Lockhart in his first edition of Scott’s life (chapter 34). Braxfield was one of the judges at Hay’s trial, but he had nothing to do with the checkmate.’

In “Lord Braxfield: The Original Weir of Hermiston” (The New Review, October 1896, pages 437-450), Francis Watt put to rest the Braxfield attribution and is, as far as I can trace, the first to suggest that the comment was made as an aside to Braxfield and not directed at the condemned man. From page 443:

“This story was told in the first edition of Lockhart’s Life of Scott; but Lockhart afterwards expressly apologized to the family for it. Braxfield, it seems, could not play chess at all and the anecdote belongs to another judge, and sets forth, I fancy, an aside to Braxfield, who was present at the trial.”

This brings us to Henry Grey Graham’s heightened retelling in 1901 (cited in C.N. 6968), relishing in the horror of the judge who “dearly loved the ‘hanging circuit’”.

Peter Stein’s 1957 article on the 1780 trial in the Juridical Review (also mentioned by Pritchett) seems to come to the same conclusion as Watt’s and Graham’s “fancy” about the circumstances of the “checkmate” utterance as an aside, but he suggests that it may have been delivered out of the condemned man’s hearing, issued out of “quiet reflection” rather than the vicious cruelty of a “hanging judge”.

The reading of this anecdote has shifted considerably over the years. The anecdote served as the basis of an even more fanciful work, “Checkmate” by Moray McLaren, on pages 66-71 of Scottish Short Stories edited by Fred Urquhart (London, 1957). A judge, named Lord Karnockie, is jealous of Kames’ famous witticism and hopes, in the presence of Kames and Braxfield, to do one better. He is presented with a condemned gentleman accused of manslaughter, named Wattie Stewart, to whom Karnockie always lost at chess. Wattie, however, is able to take revenge in the courtroom, which forces a new and final witticism from the hanging judge.’

We add that an extensive passage from Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, including the ‘checkmate’ story, was quoted on pages 238-240 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1842. The anecdote was not mentioned in ‘Sir Walter Scott on Chess’ by H.R.H. on pages 530-531 of the December 1891 BCM (an article included in Reinfeld’s The Treasury of Chess Lore) but was discussed by the magazine in 1907 (January, page 23 and February, pages 67-69).

7015. Jonathan Penrose

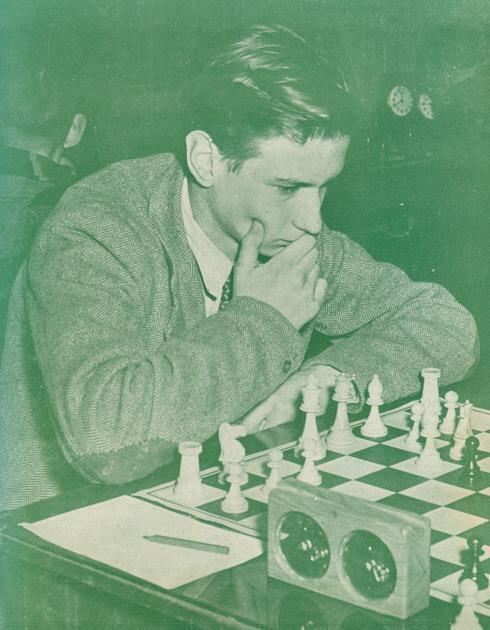

From the front cover of Chess Review, May 1950:

7016. Alekhine interview (C.N. 7013)

Wayne D. Komer (Toronto, Canada) and Stephen Wright (Vancouver, Canada) have provided the interview with Alekhine by Archibald Lampman, as published in the Toronto Daily Star, 14 November 1932, page 3.

We have transcribed the full text:

‘World’s Champion is Here to Play Chess Blindfolded

Alekhine Hasn’t Even a Board, But He’ll Play 40 Boards Tonight

Sentenced to DieBy Archibald Lampman

‘The world’s champion chessplayer blew into town today without even a chess board, or any idea where to get one. He has a sunny smile and a date to play 40 boards simultaneously against Toronto’s chess elite tonight. And just to show he’s not fooling, he’ll play a couple of games blindfolded. He’s Dr Alexander Alekhine and he’s wondering how to put in the time till his engagement. He thinks he’ll play bridge.

Banish forever mental pictures of chess champions with deep, brooding eyes, who make slow motion look like a fourth alarm. It’s the bunk. As we chatted with Dr Alekhine in the King Edward rotunda today he told us chess was a grand game if you didn’t take it too seriously.

Seeing the World

In a whirlwind finish (for chess) Dr Alekhine relieved Capablanca of the world’s title in Buenos Aires in 1927. Since then, as far as we gathered from the doctor’s discourse, he has been having a good time seeing the world, not letting chess get him, and feeling lucky that he made a success of his chosen vocation. He’s a qualified lawyer, an exile from Russia of noble birth, now a French citizen, and has a 12-year-old son, Alexander, back in Paris, who can’t play chess for nuts and is proud of it.

“Are you good at figures, doctor?”, we asked. “I mean are you one of those chaps who can juggle a hatful and know all the answers?”

“No good at mathematics at all”, he says surprisingly. “No good at any of the exact sciences.” “Well, don’t you call chess an exact science?” “No, it’s an art. I’m pretty good at philosophy and all the abstract sciences.”

“Tell us, doctor – how do you train for these big bouts?” “Train? I don’t train – I knew all about it long ago – I haven’t even got a chess board.” Anybody lend the doctor a chess board?

“You mean to say you won’t slip upstairs and have a couple of rounds of shadow boxing with the chess board before you encounter the boys tonight?” He laughed. “I don’t know how I’ll put in the time – maybe play a little bridge.” “Good at bridge?” “Just a fairly good player.”

Eats No Brain Food

“Eat anything special for these tilts – brain food, for instance?” There’s a catch somewhere – we know. “No.” “What about coffee?” “Oh, I drink coffee sometimes during the game.” Then he fooled us again. “But just because I like it.”

He says any master of chess could play these massed formation games. And they are just about 40 recognized masters in the world. New York, he says, is probably the world’s greatest chess centre now. “And Toronto?” “Tell you tomorrow”, he says.

“I played 50 boards four to a board in New York”, says he. “Consulting playing – the four to each board consulted on each move against me.”

“Tired after?” “Yes – a little”, he admits, “it was about the hardest I’ve played.” But then he played 60 boards in Paris with five to a board and says he felt fine afterward.

“Ever dream about chess?” For instance tonight’s game will take him six hours or so. “No – say that’s the funny part – I dream about everything else – bridge, tennis, everything.” So, if you dream about chess, that would seem to let you out – as a chessplayer.

Women Not Good Players

“Women good at chess?” “No – they’re not”, he says smiling. And, by the way, if all the Moscow lads smile like that, the home town can’t be so bad after all. “And that’s funny too – because they’re good at bridge and other things – but not chess.” “Just another mystery.” “About women?” “Yes, just one more.”

He has a library of 1,600 books on chess. “Read them all?”, we asked. “No”, he says off-hand, “I know what’s in them.” He has written eight books on chess himself.

“Anybody around the world now that can beat you, do you think?” “No, I don’t think so. I have beaten them all”, he says, although I only beat Capablanca by a small margin. I just want to hold my own against my own generation. If one of the younger generation came along and beat me – well – .” He shrugged a shoulder. “I don’t care.”

“No hard feelings, eh, toward the youngsters?” “No; none at all.”

Has “Off” Moments

He doesn’t always win all the games in a massed contest. He says he has his “off” moments, just like anybody else.

“About how many wins would you average?” “H-m-m – about 80%. I don’t know.”

“One mustn’t take chess too seriously”, he says, just as though he didn’t care.

“Not like they do in bridge”, we suggested. “Not like some people do”, he corrected. Although the rules of chess have been the same for a couple of thousand years, the technique has changed in the last 70 years, when it became of international interest. You’ve got to study the players as well as the board.”

“Didn’t Haroun Al Raschid study his antagonist?” “No; they just looked at the board.”

He says chess originated in Persia.

We switched to the man himself. By the way, he smoked one cigarette after another as he talked to us – if that’s any help to you chess aspirants. And so did we, if that’s any interest. “You come from a noble family?”, we opened tentatively, as you can’t tell how people are going to look on this kind of thing.

“Yes – my father was marshal of Voronesh”, he says, “Russia under the czar was divided into states – my father was head of one of those states.”

Under Death Sentence

“Did your family suffer a lot in the revolution?” No – not so much. I was sentenced to death”, he says, something like “The traffic cop hands me a ticket, see.” “Sentenced to death! – well, how did you get out of that?” We had to arouse some interest in the man about his own death sentence. He just shrugged his shoulder. “Blew over, eh? – this shooting business?” He laughed his sunny laugh again. “Yes – just blew over.”

He was an officer in the German [sic; the Chess World corrected this to Russian] army. He’s 40 now, so he couldn’t have been any veteran then. He’s also a reserve officer in the French army as well as being a lawyer. So that’s why he doesn’t care whether he wins or not. Twelve years ago he left Moscow for the last time.

“I’m practically an exile now”, he says, as though exiling was a great sport. “Why’s that?”, we asked. “Just because they don’t like you?” “No, they don’t like me – and I’m anti-Communist.”

He says in the old days there’d be about a million grade A chessplayers in Russia. Moscow was a great centre. “Didn’t the Soviets do something about the chess boards – kings and queens and everything?” “No, they didn’t worry about them. They still play chess.”

Started at Age of Seven

Dr Alekhine started to play chess at the age of seven. The family made him quit. “I was always good”, he said, as naturally as you’d say, “I’m punk at bridge”. He began again at 12. They let him go to it. He joined the local club at 15. And at 16 was a master of chess. Tie that.

“Was your dad good at chess?” “He played, but he wasn’t much good”, he said. By the way, there have only been seven or eight chess champions in the last 250 years. It’s not one of those things you rush into.

“When are you going to quit?” “Oh, I don’t know – perhaps I’ll practise law later on.” He’s going to the Far East to clean up on Gandhi’s crowd and then the Aussi playboys.

“Sure you’re not worrying about tonight?” He grins – jaunty, we call it. “Not much”, he says, and grabs our hand.’

7017. The earliest Caro-Kann Defence (C.N. s 2188 & 2389)

We are still looking for very early specimens of 1 e4 c6. The first occurrence found so far (see page 89 of A Chess Omnibus) was between unnamed players, published on pages 336-337 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1845 (not 1846). It began 1 e4 c6 2 d4 e5 3 dxe5 Qa5+ 4 Nc3 Qxe5 5 Nf3 Qc7, bringing about a position which, as mentioned in C.N. 2389, arose in the simultaneous game Fischer v Fajkus, Cicero, 1964.

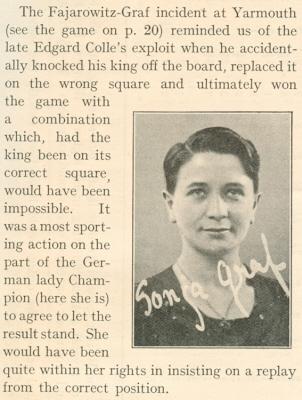

7018. An incident at Yarmouth, 1935

Below is an article by the Badmaster, G.H. Diggle, from page 28 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984). It originally appeared in Newsflash, November 1977.

‘The BCF Congress at Yarmouth, 1935, really was done in style. The Mayor and Mayoress and their “able assistants” put on a royal show on the opening day; 150 guests sat down to tea; the Mayor and Canon Gordon Ross (President, BCF) made “topping speeches”; a musical programme was provided; and there was even an “OYEZ” Official posted at the entrance who first whispered to the BM “May I have your name, sir?” and then announced to the assembly in stentorian yet fruity tones: “MR BEDMAISTER & FAMILY!!” Though no-one in fact took a blind bit of notice, it “made the BM’s day”.

The British Championship was won by W. Winter, who (perhaps in deference to the high sartorial standard at the Congress) appeared most immaculate throughout, clean-shaven in a smart blazer and grey flannels. He scored 8½, followed by Sir George with 7½ and H. Golombek, A. Lenton and R.P. Michell (7). The Ladies’ Championship went to Mrs Michell. Other Sections were full of well-known names – the Major Open Reserves included H.V. Mallison, C.S. Damant, W.H. Watts and S.D. Ward (who recently celebrated 50 years’ membership of the Bury and West Suffolk C.C.); in the First Class were John Keeble (a prize-winner in his 80th year) and Rev. A.P. Lacy Hulbert; in the Third Class, A. Aird Thomson (with a clean score of 11), followed by G. Veglio with 10. But the most remarkable sideshow was the Major Open. Nine out of the 12 competitors were foreigners, and included the young Reshevsky, Dr Seitz, Vera Menchik, A.G. Condé, E. Klein and the popular Sonja Graf. Great Britain was represented by B.H. Wood, A.J. Butcher (who, the BM remembers, put up a stout fight against Reshevsky in the opening round) and F.E.A. Kitto. Reshevsky came first with ten points out of 11, losing only to V. Menchik on time-limit – “in this respect”, wrote A.J. Mackenzie, “he constantly sails so near the wind that he was bound to be caught some time”.

There was one “incident”. In a very interesting adjourned game between Sonja Graf and her compatriot Fajarowitz, the position was put down wrongly in the sealed envelope. Neither player noticed when the game was resumed from the wrong position, and it ended in a draw. But in the meantime some interested pundits had set up the right position from memory and found a dead win for Sonja in all variations. When “the balloon went up” about this later, she could under FIDE Rules have demanded a replay from the correct position but “the Munich lady sportingly elected to abide by the drawn result already reached”.’

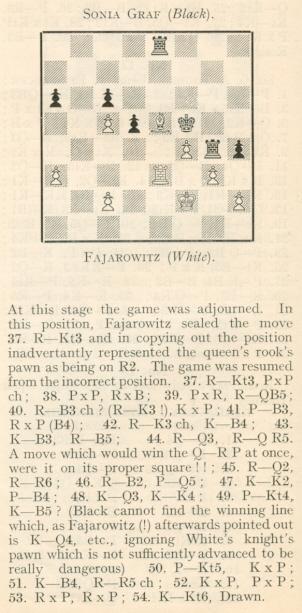

The ‘incident’ in the game between Fajarowitz (Fajarowicz) and Graf was discussed on pages 356-357 of the August 1935 BCM:

‘A difficult decision under the FIDE laws of chess was avoided. In the adjourned game between Fajarowitz and Fräulein Graf the position for sealed move purposes was put down wrongly. (Rule 21 (iv) makes both parties responsible for its correctness.) However, on resumption this position was set up on the board, the game finished and drawn. The game had been of much interest and a number of parties were sufficiently interested to hold “post mortems”, setting up from memory the correct position. Later the two players joined in, and a dead win in all variations was established for Sonja Graf. And then they learnt first about the incorrect diagram. Rule 21 (viii) says if the position be reinstated incorrectly all the subsequent moves are annulled and the game has to be resumed from the correct position. A claim to replay was at first made, and the officials were called on to decide the point. The complication of the after-analysis, with the extra difficulty that the exact winning lines were known, would have made a decision rather troublesome, but the Munich lady recognized the unfairness to Fajarowitz involved and sportingly elected to abide by the drawn result already reached. Any other course would have led to a very ironic position, since Fajarowitz himself was the chief agent in establishing the winning lines for his opponent.’

The adjournment position was given on page 20 of CHESS, 14 September 1935:

On page 3 of the same issue Sonja Graf’s ‘sporting action’ was praised:

The famous Colle game referred to was, in fact, lost by him. It was his opponent, A. Steiner, who placed his king on the wrong square, at Budapest, 1926. See, for instance, Znosko-Borovsky’s report on page 132 of L’Echiquier, July as well as accounts in many popular books, such as on page of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974).

7019. Pronouncing Euwe

From page 3 of the 14 September 1935 CHESS:

‘For the benefit of those to whom Dutch pronunciation is a trouble, we might mention that “Euwe” is pronounced like “Minerva” without the “Min”.’

Some verse by H.D’O. Bernard was published on page 47 of the February 1941 BCM:

‘A Dutchman exclaimed with some fervour –

“When writing to our Doctor Euwe

Kindly say it’s untrue we

Pronounce it as Youwe

It is rather more Yerver than Erver.”’

C.J.S. Purdy discussed the matter on page 137 of Chess World, 1 June 1950:

‘Euwe. There is no way of anglicizing this famous name satisfactorily, so the best idea is to get reasonably close to the Dutch. The “eu” is not pronounced “oy” as in German, but is a seasick sound between “oy” and “ee”. The “w” is between “w” and “v” and nearer “w”, Dr Euwe has explained to us. If you listen to a Dutchman you’ll hear him glide over it so lightly that you can take your pick. The normal English “near enough” pronunciation is “Erva” as in “Minerva”.’

On page 357 of the December 1958 Chess Review J.S. Battell stated, ‘Euwe in Roman alphabet, pronounced Er-va’. The first edition of The Oxford Companion to Chess (page 105) had ‘ervour as in fervour’, whereas the second edition (page 126) gave ‘erwe as in Derwent’.

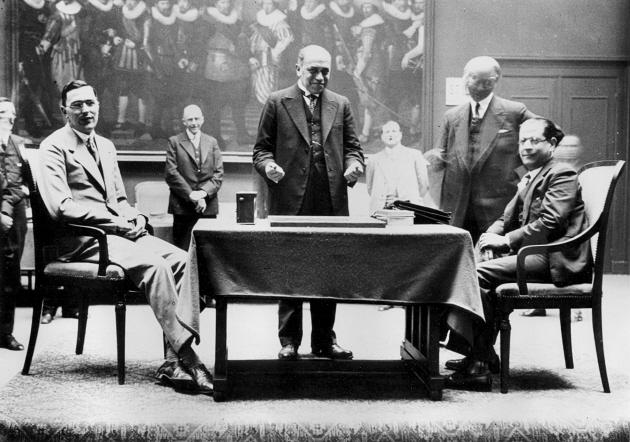

From our archives comes this photograph of Euwe during his match with Capablanca in 1931:

7020. Chess Notes items

We are very grateful to Michael Syngros (Amarousion, Greece) for compiling a list of Chess Notes items written since the column first appeared online, in 2002. The compilation will be updated and expanded from time to time.

7021. Who?

| First column | << previous | Archives [80] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.