Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [92] | next >> | Current column |

7537. In Memoriam (C.N. 7497)

The two-volume set In Memoriam by David DeLucia has now been published, in a limited edition of 150 copies. It is available either direct from the author (we are happy to continue passing on enquiries) or from the Caissa Editions Bookstore. At that website, Dale Brandreth, a leading chess bibliophile, provides his assessment of In Memoriam, with many justified superlatives. It is truly a phenomenal production.

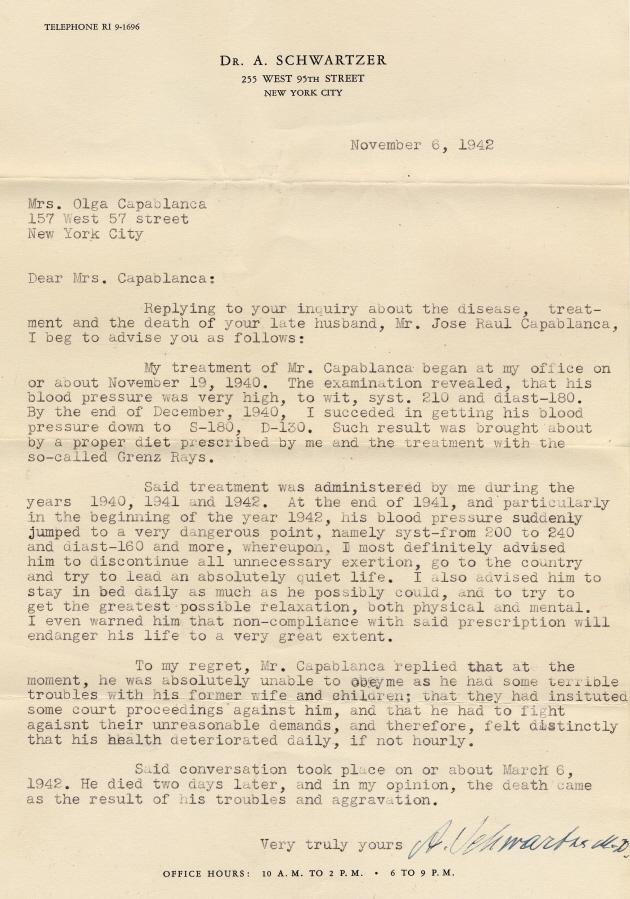

With regard to Capablanca’s death, we are grateful to Mr DeLucia for permission to publish here, from page 265 of volume two, a letter dated 6 November 1942 from Dr A. Schwartzer to the Cuban’s widow:

Mr DeLucia has also kindly allowed us to reproduce (from volume two, page 239) this photograph of Capablanca inscribed in May 1933:

7538. Lessing v Jaffe (C.N. 7530)

Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA) notes that the conclusion of the Lessing v Jaffe game is on page 191 of The World of Chess by A. Saidy and N. Lessing (New York, 1974).

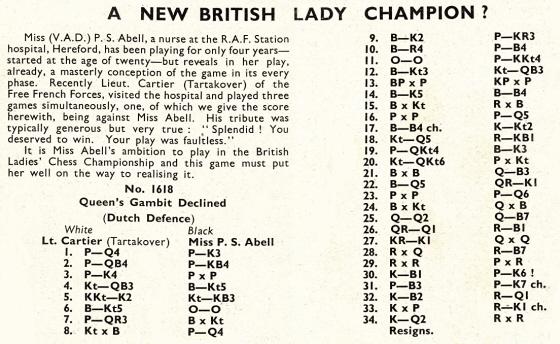

7539. P.S. Abell

A new field for research:

Source: CHESS, September 1943, page 185.

1 d4 e6 2 c4 f5 3 e4 fxe4 4 Nc3 Bb4 5 Nge2 Nf6 6 Bg5 O-O 7 a3 Bxc3+ 8 Nxc3 d5 9 Be2 h6 10 Bh4 c5 11 O-O g5 12 Bg3 Nc6 13 cxd5 exd5 14 Be5 Bf5 15 Bxf6 Rxf6 16 dxc5 d4 17 Bc4+ Kg7 18 Nd5 Rf8 19 b4 Be6 20 Nb6 axb6 21 Bxe6 Qf6 22 Bd5 Rae8 23 cxb6 d3 24 Bxc6 Qxc6 25 Qd2

25...Qc2 26 Rad1 Rc8 27 Rfe1 Qxd2 28 Rxd2 Rc2 29 Rxc2 dxc2 30 Kf1 e3 31 f3 e2+ 32 Kf2 Rd8 33 Kxe2 Re8+ 34 Kd2 Rxe1 35 White resigns.

7540. Who? (C.N. 7517)

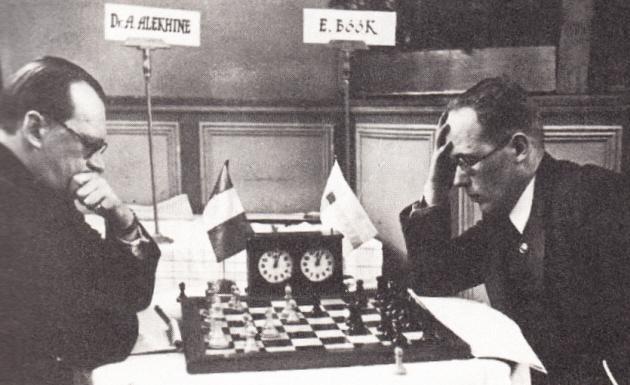

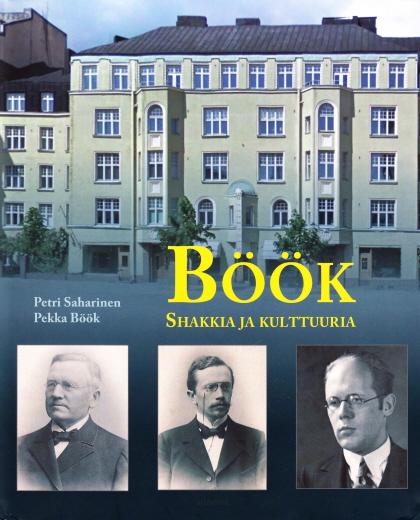

This photograph depicts the famous brilliancy Alekhine v Böök, Margate, 1938. Our source is page 23 of Böök’s volume Mestarin mietteitä (Järvenpää, 1985). See too pages 190-191 of the finely produced work Böök Shakkia ja kulttuuria by P. Saharinen and P. Böök (Helsinki, 2010).

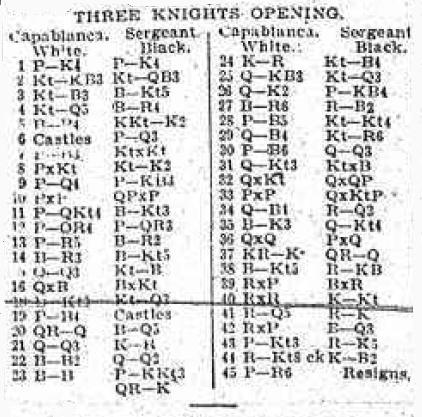

7541. Capablanca v Sergeant

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) has found this game on page 3 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 28 August 1919:

The moves are garbled at the end of the first column. Our correspondent suggests that the most likely missing move is 16 h3, which gives the following:

José Raúl Capablanca – Philip Walsingham SergeantSimultaneous exhibition, City of London Chess Club, London, 6 August 1919

Three Knights’ Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Nd5 Ba5 5 Bc4 Nge7 6 O-O d6 7 c3 Nxd5 8 exd5 Ne7 9 d4 f6 10 dxe5 dxe5 11 b4 Bb6 12 a4 a6 13 a5 Ba7 14 Ba3 Bg4 15 Qd3 Nc8 16 h3 Bxf3 17 Qxf3 Nd6 18 Bb3 O-O 19 c4 Bd4 20 Rad1 Kh8 21 Qd3 Qd7 22 Bc2 g6 23 Bc1 Rae8 24 Kh1 Nf5 25 Qf3 Nd6 26 Qe2 f5 27 Bh6 Rf7

28 c5 Nb5 29 Qc4 Na3 30 c6 Qd6 31 Qb3 Nxc2 32 Qxc2 Qxd5 33 cxb7 Qxb7 34 Qc4 Rd7 35 Be3 Qb5 36 Qxb5 axb5 37 Rfe1 Red8 38 Bg5 Rf8 39 Rxe5 Bxe5 40 Rxd7 Kg8 41 Rd5 Re8 42 Rxb5 Bd6 43 g3 Re4 44 Rb8+ Kf7 45 a6 Resigns.

The newspaper stated that the game-score had been supplied by J. Walter Russell. The report of the séance on page 298 of the September 1919 BCM provides the information that Black was Philip W. Sergeant.

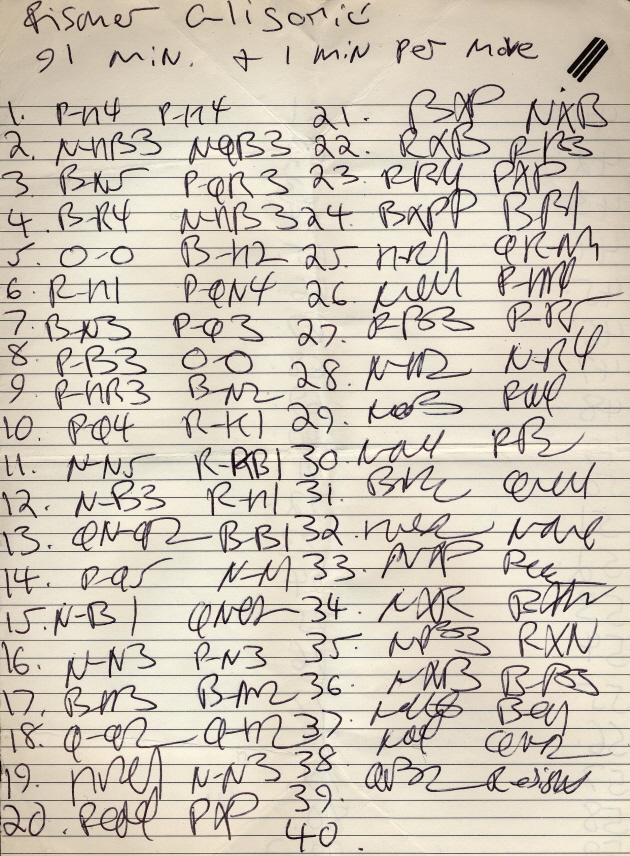

7542. Fischer v Gligorić

Pages 180-181 of Bobby Fischer Uncensored by David DeLucia (Darien, 2009) gave three training games played by Fischer and Gligorić, and now page 332 of volume two of the further work In Memoriam (see C.N.s 7497 and 7537) has another game-score, with the caption ‘Unrecorded training game, Fischer-Gligorić 1992, written in Fischer’s hand’. It is reproduced below with Mr DeLucia’s permission:

We have been unable to decipher the full game. Can any reader work it out?

7543. Fischer v Gligorić (C.N. 7542)

Two attempts to unravel the moves played in the 1992 Fischer v Gligorić training game have been received.

1) From Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA):

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 d6 8 c3 O-O 9 h3 Bb7 10 d4 Re8 11 Ng5 Rf8 12 Nf3 Re8 13 Nbd2 Bf8 14 d5 Nb8 15 Nf1 Nbd7 16 Ng3 g6 17 Be3 Bg7 18 Qd2 Qe7 19 Nh2 Nb6 20 a4 bxa4 21 Bxa4 Nxa4 22 Rxa4 c6 23 c4 cxd5 24 cxd5 Bc8 25 Rea1 Rb8 26 R1a2 h5 27 f3 h4 28 Ne2 Nh5 29 R4a3 f5 30 Ra4 Rf8 31 Bf2 Qf7 32 Nf1 fxe4 33 Rxe4 Nf6 34 Rxh4 Bb7 35 Nc3 Nxd5 36 Nxd5 Bxd5 37 Rxa6 Bf6 38 Rg4 Be6 39 Ra7 Qe8 40 Qh6 Resigns.

2) From Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium):

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 d6 8 c3 O-O 9 h3 Bb7 10 d4 Re8 11 Ng5 Rf8 12 Nf3 Re8 13 Nbd2 Bf8 14 d5 Nb8 15 Nf1 Nbd7 16 Ng3 g6 17 Be3 Bg7 18 Qd2 Qe7 19 Rf1 Nb6 20 a4 bxa4 21 Bxa4 Nxa4 22 Rxa4 c6 23 c4 cxd5 24 cxd5 Bc8 25 Rfa1 Rb8 26 Ne1 h5 27 f3 h4 28 Ne2 Nh5 29 Nd3 f5 30 Nb4 f4 31 Bf2 Qg5 32 Kh2 Ng3 33 Nxa6 Bd7 34 Nxb8 Bxa4 35 Nc3 Rxb8 36 Nxa4 Bf6 37 Nb6 Bd8 38 Nc4 Qe7 39 Qc2 Resigns.

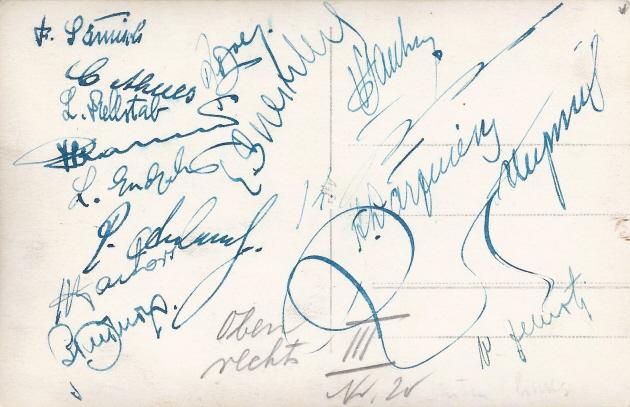

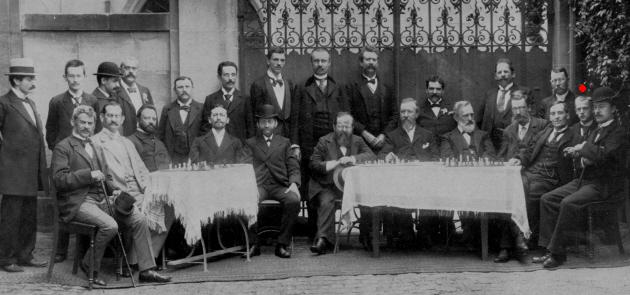

7544. A challenge

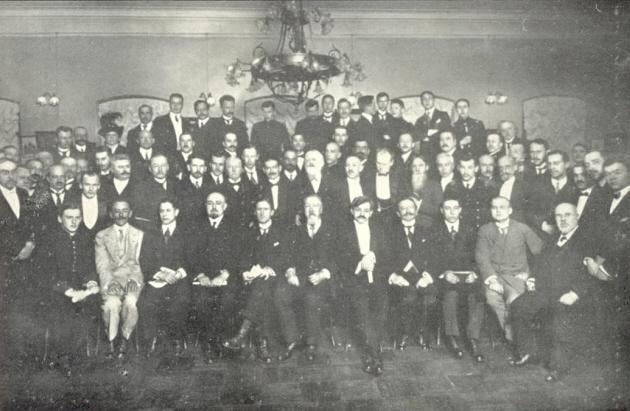

John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) offers readers the challenge of identifying as many figures as possible in this photograph:

The card has been provided courtesy of Mr Valdemars (Val) Zemitis (Davis, CA, USA).

7545. The Edge libel case (C.N. 7483)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘Further to my short account of the libel case which F.M. Edge brought against Clayton in 1867 (see Notes on the life of Howard Staunton, pages 119-120), I have learned a little of the background to the case. Although Edge had been released from the debtors’ prison about March 1866 (see C.N. 7483), his financial position continued to cast dark shadows over his life and was the cause of his departure from his job at the Reform League, which involved collecting money and retaining a percentage for himself, and the consequent libel action.

A fairly detailed account of the case appeared in the Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser of 7 August 1867, page 4. This included, incidentally, the full text of his resignation letter, dated 11 January 1867, which, in a chance remark by Edge, provides further evidence that he was married (“… I must now seek the means for maintaining myself and those dependent upon me …”). The identity of his wife remains a mystery.

According to the newspaper article, his counsel made the point that the advertisement inserted by his employer to announce his departure was libellous because, by the manner of the League’s distancing itself from Edge, it created a situation in which any monies subsequently collected by him could be seen as not for the benefit of the Reform League at all and, hence, it would be thought that he was acting dishonestly.

The discussion turned to the matter of some money which Edge had borrowed from a certain Mr Clinch:

“The plaintiff had been to Mr Clinch and borrowed £15 on a promissory note payable on 2 February. The money was lent to enable the plaintiff to deliver his lecture on 31 January. For some reason or other the plaintiff had postponed the day of the lecture to 6 February, and Mr Clinch not seeing any advertisement of the lecture in the papers, went to the League office on 28 January to inquire about Edge.”

It becomes clear from W.J. Clinch’s evidence that Edge had acquired a bad reputation for borrowing money while he was working for the Reform League:

“… He inquired for Mr Edge. They told him he was not there, and spoke of him in such a manner as to arouse his suspicions. Clayton told him the fact was that Edge had been borrowing money from first one person and then another, and Mr Jacob Bright had been told his association with him would not be creditable. … Crossley said if he would push him he would get the money, because he would let in someone else. Witness added that he was afterwards examined by the executive committee as to whether he did not lend the money on the strength of the plaintiff being an agent for the League. His answer was that his connection as an agent for the League would be no inducement to him to lend money (Laughter).”

Edge cleared his name, a settlement coming about as a result of a suggestion from the judge. However, this description of his borrowing habits and his bad reputation, taken together with his earlier imprisonment for debt, raises further questions about Edge’s trustworthiness, which several chess historians had already doubted. He played a central part in the Staunton-Morphy controversy.’

7546. A letter from Henry Adams (1838-1918)

John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) also contributes a passage about Edge, from page 410 of volume one of The Civil War by Brooks D. Simpson, Stephen W. Sears and Aaron Sheehan-Dean (New York, 2011). It is in a letter which Henry Adams (who was serving as his father’s confidential secretary during the latter’s term as minister to Great Britain in Lincoln’s Administration) wrote in London on 10 June 1861 to his younger brother Charles Francis Adams Jr.:

‘I have tried to get some influence over the press here but as yet have only succeeded in one case which has however been of some use. That is the Morning Herald, whose American editor, a young man named Edge, came to call on the Amb. He is going to America to correspond for his paper; at least he says so. If he brings you a letter, let him be asked out to dine and give him what assistance in the way of introductions he wants. He is withal of passing self-conceit and his large acquaintance is fudge, for he is no more than an adventurer in the press; but his manners are good, and so long as he asks nothing in return, it’s better to have him an ally than an enemy.’

On page 5 of his book about Morphy (New York, 1859) Edge referred to his work for the Herald, and John Hilbert comments that although the index to The Civil War (page 799) merely refers to ‘Edge (Editor)’ it can hardly be doubted that it was F.M. Edge.

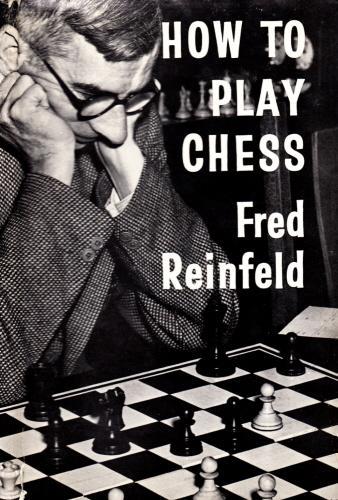

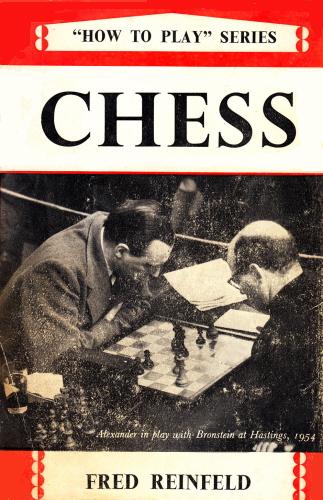

7547. Reinfeld book

This is the front of the dust-jacket of Reinfeld’s How to Play Chess, which was published by Eyre & Spottiswoode, London in 1954 and reprinted in 1959. Elsewhere the dust-jacket states that the photograph was ‘reproduced by courtesy of Kemsley Picture Service’, but who is the player shown?

We have consulted Leonard Barden (London), who feels

60-70% sure that it is W.J. Fry. The winner of the

Southampton championship ten times, Fry died on 29 October

1954 at the age of 58. Brief obituaries were published on

page 116 of CHESS, 27 November 1954 and on page

382 of the December 1954 BCM.

Reinfeld’s book had been published in the United States in 1953 under the title The Complete Chessplayer, but with a different dust-jacket.

7548. Botvinnik v Model

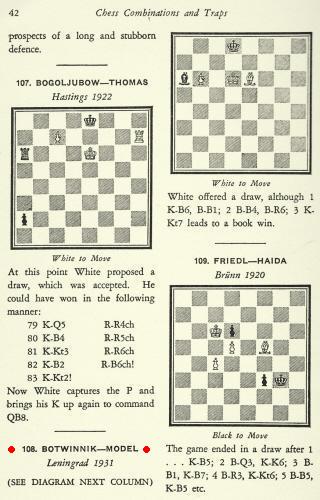

Below is page 42 of a book edited by Reinfeld, Chess Combinations and Traps by V. Ssosin (New York, 1936):

What more is known about the Botvinnik v Model position? We wonder whether it arose later in the game which was given in part on page 217 of Botvinnik’s Complete Games (1924-1941) and Selected Writings (Part I) (Olomouc, 2010):

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Qb3 c5 5 dxc5 Nc6 6 Nf3 O-O 7 Bg5 Qa5 8 Bxf6 gxf6 9 e3 Qxc5 10 a3 Qa5 11 Rc1 Be7 12 Be2 Kh8 13 O-O d6 14 Rfd1 Ne5 15 Ne4 Bd7 16 Qc3 Qc7 17 Nxe5 fxe5 18 Nxd6 Bxd6 19 Qd3 Bxa3 20 Qxa3 Bc6 21 Rd6 Rg8 22 f3 Qe7 23 Rcd1 Qg5 24 g3 Rg7 25 e4 Rag8 26 Qxa7 Qh4 27 g4 h5 28 Qf2 Qg5 29 h3 hxg4 30 hxg4 Rh7 31 R6d3 f5 32 Qg2 fxg4 33 fxg4 Qf4 34 Rh3 Rxh3 35 Qxh3+ Kg7 36 Qf3 Bxe4 37 Qxf4 exf4, and the game was subsequently drawn.

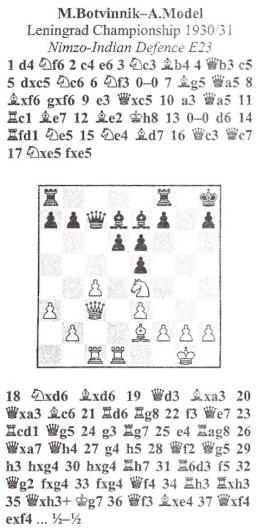

7549. Caricature

Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, Italy) forwards this caricature of Capablanca from page 15 of the Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten of 24 March 1927:

7550. Capablanca speaks (C.N. 6862)

Since the link to the Geschiedenis 24 website given in C.N. 6862 required updating, we take the opportunity to provide here a direct link to the only video-and-sound interview with Capablanca known to us.

7551. Medicine Men

This article by G.H. Diggle was published in Newsflash, August 1976 and on page 14 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘The Badmaster’s first ever Correspondence Game, played for a Minor County at the age of 17, was a “horrific experience”. With fluttering heart he opened the “official envelope” containing the name and address of a far distant and mysterious opponent, and he eagerly devoured the accompanying “Rules and Regulations” at least two dozen times over. “A player” (to quote the Act) was entitled to consult chess works, but to receive “no other assistance whatsoever”. The BM proudly resolved that (whatever others got up to) his genius should never be contaminated by outside advice. But alas, it soon was, and “the wages of sin was resignation” (on the 30th move).

In fairness to the BM it must be pointed out that he was then by some 20 years the youngest member of a provincial club, that in those glorious days (would they were with us again!) young players stood in awe of old ones (who patronized and bullied them dreadfully), and that the BM was constantly tempted by spurious local grandmasters and false “Medicine Men” who would “wait for his unguarded hours” and demand to be shown his position. The worst of them was a local shopkeeper (and lay preacher) whose recreations were chess and hypocrisy. He was one of those men who could see right through a position before you had even set it all up. “I was thinking of going there ...”, faltered the BM timidly. “Rubbish, young man, rubbish!”, roared “Nestor”. “Here’s your move, boy, here! Sews him up completely!” “So you think that ...” “Suttonly, suttonly”, he burst forth aggressively, “Why, you must win a piece in two moves – you can’t help but win a piece in two moves! Oh, bless your life, etc. etc.” The BM, after suffering pangs of conscience (but not daring to send his own move as he knew it would all come out at the next inquisition), dispatched the one prescribed by “higher authority”. A few days afterwards he visited the sage’s shop and complained that he had not won a piece in two moves after all. “Haven’t you really, now?”, rejoined that worthy in a tone of polite commiseration (as though he had never had anything to do with it at all). “But”, hinted the BM delicately, “I thought I was bound to win a piece in two moves.” “Now, now, Mr Bad”, replied the unabashed mentor, “When you have played chess for a few more years (here his manner became most impressively and portentously solemn) you’ll discover that in chess, as in everything else, the Mills of God grind slowly!” This homily he wound up with a great asthmatical sigh – and the BM could only steal from his presence on tiptoe, leaving him to finish his sublime train of thought in seclusion, and feeling utterly ashamed of ever having doubted the wisdom of such a man.’

7552. Fischer v Gligorić (C.N.s 7542 & 7543)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) writes:

‘In Mr Winants’ reconstruction there are many moves which, with hindsight, I find more recognizable from the original score-sheet than in my own attempt. For example: 29 NQ3, 31…QN5, 32…NN6, 34 NxR, 35 NB3! (and not 35 Rxa4 Nf1+), and 39 QB2. Even the mysterious rook move 19 Rf1 would match the apparent 19 RB1.

So I think that, short of obtaining from Gligorić himself a different version of the game, Mr Winants’ reconstruction should be taken as the true score. My congratulations to him.’

7553. Boncourt

In C.N. 2002 (see page 318 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) information was requested about Boncourt, a leading player in Labourdonnais’ time. Nothing of substance came to light, and it is only now, thanks to Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France), that we have learned his full name and information about his death: Hyacinthe Henri Boncourt died in the 11th arrondissement of Paris on 23 March 1840.

Further details are available at Mr Thimognier’s new webpage on Boncourt.

7554. Hans Frank

Regarding Hans Frank, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) notes on a Dutch website a better version of the photograph given in C.N. 5533.

7555. A challenge (C.N. 7544)

John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) writes:

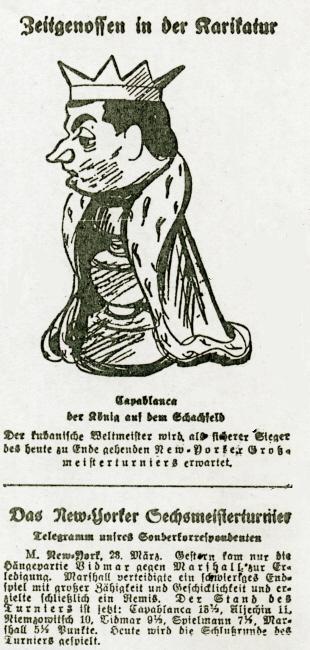

‘Val Zemitis is able to recall most of the names in connection with this forgotten tournament, which, according to his records, was played in Oldenburg on 10-25 August 1946 and was won jointly by Sämisch and Ahues, ahead of Rellstab:

Standing (left to right): Ozols, Endzelīns, Liepnieks, Skema, Arlauskas, Krūmiņš, Darznieks, Sneiders, Rankis, Dartavs, Tautvaišas, N.N, Zemitis.

Seated: N.N. (a tournament official), Rellstab, Sämisch, Ahues.’

Below is the crosstable which Val Zemitis prepared at the time:

7556. Fischer v Gligorić (C.N.s 7542, 7543 & 7552)

Further comments having been received on the reconstruction of the Fischer v Gligorić training game, for ease of reference we are grouping everything together in a feature article.

7557. Capablanca on Lasker, Tarrasch and

Teichmann

Gene Gnandt (Houston, TX, USA) has found an article by Capablanca on page 9 of the Evening Post (New York), 22 July 1916. We have transcribed it below:

‘Emanuel Lasker in a Contemporary’s Eyes

Chess master not a peculiar type of individual

Capablanca, the Cuban Player, in an Estimate of the Abilities of the World’s Champion – His Personal Characteristics – Tarrasch and Teichmann as They Appear in Tournaments – Tarrasch, Only, Prepares for ContestsBy José Raoul Capablanca

I have frequently heard the remark that a chess master must be a peculiar type of individual. He must not be one who sticks close to the golden mean of conduct, but rather one who approaches extremes, if not in physical, at least in mental, characteristics. With this statement I must say on the strength of my associations with the chess masters of the world, that I am not wholly in accord. It is true that they are, with few exceptions, men of great mental powers.

In this connection there come to my mind the mental pictures of three of my worthiest German opponents – Emanuel Lasker, Tarrasch and Teichmann. I shall speak of these three not only because their pre-eminence demands it but also because my observation of them makes me believe that they possess some of that picturesqueness and oddity suggested by the usual caricature of the chess master.

Lasker, to my mind, is the typical Bohemian, chastened, however, by a large fund of common sense and knowledge. He is one of those long-haired individuals indifferent to dress, a brilliant conversationalist, an inveterate smoker of cigars, and sipper of black coffee, one whose person seems to be an appropriate decoration of a Bohemian café – a Samuel Johnson, without his discourtesy, transported to a Russian café.

Lasker’s conversational powers

Lasker’s conversational power is exercised in a peculiar way. One must first engage him in conversation before he will talk. He is not of that kind of conversationalist who approaches another and, by the brilliance of his talk, gathers around him a host of admiring auditors. His unassuming and courteous manner is not calculated to produce this sort of thing. But he would rather betake himself, unaccompanied, to a café and, like the great Napoleon, sit at one of the tables, listening to the conversation of others. Here, sometimes, Lasker prefers to do some of his thinking. Usually, however, he reserves this function for the long walks for which he is known. He is eager to know the thoughts and opinions of others, never judges them harshly; but takes them all for what they are worth. This attitude he also maintains in chess, lending a willing ear to all discussions.

As for Lasker’s picturesqueness of dress, I have been under the impression that he had long since dismissed the question of dress as one of the unnecessary annoyances of life. I recall a very amusing incident in this connection, when Lasker visited New York. He had been invited by the Manhattan Chess Club to give an exhibition of simultaneous play. Special preparations were made in his honor. That evening Lasker evidently thought the occasion worthy of his wearing a Tuxedo. As he entered the room I heard a slight titter and, looking up in the direction of the sound, I saw that Lasker had come to us that evening with his cravat untied and dangling down upon his shirt. When his attention was politely called to this, he thanked his informant very politely and, endeavoring to correct this breach of the conventions, made several quick passes with his hands in the vicinity of his throat and made a knot that passes description. In this fashion he played through the evening.

Champion a deep thinker

Furthermore, Lasker is a thinker and a philosopher of the true type – such a one as, I have often felt, Plato might have delighted in shutting up in one of his towers, far from the madding crowd, to think only for the welfare of his republic. As a matter of fact, I believe that Lasker would have liked this job, for to be a philosopher of repute is an ambition very close to the heart of the worthy doctor. His predilections, however, lie in the field of mathematics, a fact that probably accounts for his scientific accuracy and inevitableness of result when he plays chess. A professor of mathematics, his love for the subject is very keen, and his capacity for work in this connection knows no bounds. Were it not for the fact that there is an application of Lasker’s knowledge of mathematics to the game he plays I should think of him along with that mathematician whose only claim to fame was the fact that he started out – and succeeded in his attempt – to discover something in mathematics that had positively not even a suspicion of a practical application to anything in this world.

As for Lasker’s method of play, I say, what is commonly conceded, that he is a genius at chess, one well worthy of the distinction of champion of the world. As a tactician, there is no-one of equal ability. Always ready to meet an emergency, however unexpected, he never finds it necessary to come to a game weighted down with the memory of a bookful of variations. He has the faculty of anticipating sooner than his opponent the crux of a situation, and has the power of seeing more. This seems to be common knowledge among those with whom he plays; and as a consequence they seem to play under a handicap. This genius of Lasker’s is reinforced by his accomplishments in mathematics, which assist him in being extremely accurate in games that assume a special aspect, and that adapt themselves to mathematical calculation.

In my own games with Lasker, what I have said of him was verified. There was at all times evidence of his far-seeing vision, his accuracy and quickness of perception. Lasker, however, is generally but not consistently a slow and deliberate chessplayer. Yet, were it not for the fact that I have beaten Lasker at rapid chess, he would be considered the foremost rapid chessplayer in the world.

When I speak of Tarrasch, I feel that I should be very cautious, lest I say something that may offend him. For Tarrasch is one of those who outdo themselves in their efforts to appear scrupulously correct. He is extremely fastidious, sensitive and possessed of a superabundance of pride, which, I should not say, is offensive in his case. When I think of Tarrasch, I see his inevitable boutonnière, his carefully soaped moustache, his immaculate and fashionable clothes. If anything disturbed the orderly appearance of his attire, it was a crime; but if anything caused his moustache to lose its peculiar outlines, it was sacrilege. Tarrasch also believed that he was born to radiate his brilliance especially before the ladies. One day during the San Sebastián tournament a lady was announced. Immediately Tarrasch was on the qui vive. He started from his seat, drew himself up to his full height, settled himself in his clothes so that every crease and fold were in their proper places, assumed a military bearing, threw out his chest, brushed an imaginary speck from his coat and strode to the door to receive the lady. Although he was not well acquainted, he stood there delivering himself of numerous and courtly bows.

But the picture of Tarrasch during tournament play is one hard to forget. He has all the appearance of a diminutive Spartan. I have seen him in important games staring fixedly at the chess board for fully an hour, so intently that one would think his sight was piercing the table, perfectly rigid, not even the smallest muscle twitching, straight-backed and with an almost painful seriousness in his face – a living statue.

The method of Tarrasch differs from that of Lasker. To my mind, Tarrasch is a very weak tactician. Coming always well prepared to his matches, he becomes terribly flustered in emergencies and at unexpected developments. He thinks long and painfully over his moves, for to Tarrasch the loss of a game is worse than the tortures of hell. I recall at San Sebastián, when, after going through all the preliminaries of assuming a military bearing and curling his moustache, he invited me for a walk. He then discussed with me at great length the best opening for the game he was to play Vidmar on the following day.

Richard Teichmann is a player who combines the qualities of both Lasker and Tarrasch. Like Lasker, Teichmann has Bohemian tendencies. He is an accomplished linguist; cannot extend himself to his best effort unless his whiskey and soda are at close call; and is clever at all games of cards and billiards. Work is no virtue with him, despite his massive bulk. As soon as his money is gone, he sets about to play chess.

As a result of an explosion, Teichmann lost the sight of one eye. And I recall with what amusement, in the midst of a brilliant gathering at Petrograd, we received the observation of a spectator that, if Teichmann could see so much in chess with one eye, what might he be capable of if he possessed two?

Teichmann won his first tournament at Carlsbad in 1911, after 20 years of play, and only after he had gone to Switzerland to prepare himself for the event. Up till then, by a strange coincidence, he had to content himself with fourth places generally. In recognition of this achievement, his friends conferred upon him the title of Richard the Fourth.

Chess to Teichmann is a pastime pure and simple. He is a keen student of the game, but plays it mostly for the pleasure that a pastime gives. He is one of those erratic players. When he has the upper hand, his play is of the most masterly kind, but at other times he is weak. Like Lasker, he does not find it necessary to come prepared. But on account of his peculiar indifference, and his disinclination to disturb the serenity of his temperament, he frequently contents himself with a draw.’

7558. St Petersburg, 1914 (C.N. 4926)

C.N. 4926 asked whether a key was available for the above photograph, which was an insert (Beilage) to the 31 May 1914 issue of Deutsches Wochenschach. A key has come to light during the preparation of a Russian translation of our article Sergei Prokofiev and Chess.

7559. Sarapu playing blindfold

Courtesy of Val Zemitis, John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) has forwarded this photograph of Ortvin Sarapu playing blindfold chess:

The picture was by Russell Orr of Hastings, New Zealand. The writing on the reverse side states that it was taken in Napier, New Zealand at Easter 1954.

7560. Kemeri, 1937

Also from Mr Zemitis and Mr Donaldson comes the following:

We were aware of a relatively poor reproduction of this item on page 250 of Schackvärlden, August 1937 (from which the picture of Karlis Ozols was extracted in War Crimes).

7561. Alekhine v Reshevsky

Page 251 of Schackvärlden, August 1937 had a photograph from the brilliancy Alekhine v Reshevsky, Kemeri, 1937:

7562. Eliza Campbell Foot (C.N. 7158)

Further information about Eliza Campbell Foot is provided in an article (with a group photograph) by Harriet A. Ver Planck on pages 65-67 of the American Chess Bulletin, May-June 1949. Her surname was spelled ‘Foote’ throughout, a variant also found in some other sources.

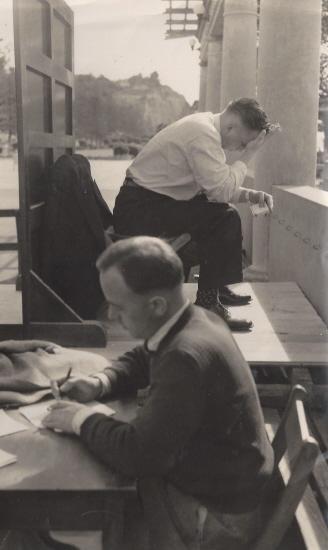

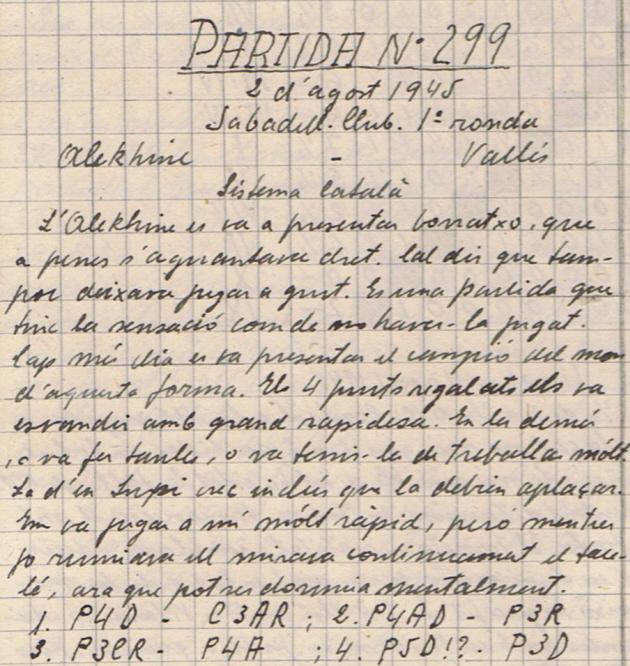

7563. Alekhine v Vallés

Josep Alió (Tarragona, Spain) informs us that he has recently acquired the third personal notebook of the Catalan player V. Vallés. It covers the period May 1942 to December 1945, and the introduction states that the first volume began in 1935.

Pages 145-156 of volume three concern Sabadell, 1945, and pages 145, 146 and 147 provide an introduction to the tournament, including Vallés’ notes to his first-round game as Black against Alekhine (1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 g3 c5 4 d5 d6 5 Bg2 Be7 6 Nc3 O-O 7 Nf3 exd5 8 cxd5 Re8 9 O-O Nbd7 10 e4 Bf8 11 Re1 Qa5 12 Bd2 b5 13 a3 Qb6 14 Qc2 a5 15 a4 b4 16 Nb5 Ba6 17 Bf1 Ng4 18 Bc4 Nde5 19 Nxe5 Nxe5 20 Be2 Bxb5 21 axb5 g6 22 Be3 Bg7 23 f4 Nd7 24 Bc4 a4 25 Rxa4 Rxa4 26 Qxa4 Bxb2 27 Bf2 Bc3 28 Re2 Qc7 29 b6 Qd8 30 b7 Nb6 31 Qb5 Nxc4 32 Qxc4 Qb6 33 e5 dxe5 34 Bxc5 Qxb7 35 fxe5 Rxe5 36 Rxe5 Bxe5 37 Bxb4 Qc7 38 Qxc7 Bxc7 39 Kg2 f5 Drawn).

Below are some extracts in our correspondent’s translation from the Catalan:

‘Alekhine turned up drunk; scarcely could he stand. It must be said that he did not let me play the game comfortably. It is a game that I have the feeling of not having played. On no other day did the world champion appear in such a state … He played very rapidly, but while I was thinking he continuously looked at the board, although he may have been mentally sleeping.’

After 31...Nxc4: ‘He now proposed a draw, but after thinking about it (moral and psychological considerations, mainly) I told him no; “Play a little more.” I think he became angry or took a dislike to me from then onwards.’

After 37 Bxb4: ‘“You want to win this?”, he asked with a scoff. I made a gesture and said, “Well, if you want a draw ...” or something like that. And then he said: “No! No! We shall play”, giving the public the impression, which was not the case, that the draw was being requested by me.’

After 39...f5: ‘And he said: “Yes, it is a draw.” And I did not know what to say, being ashamed.’

7564. Taylor v N.N.

James Stripes (Spokane, WA, USA) requests more information about the Taylor v N.N. game mentioned in C.N. 1371 and, in particular, about the identity of White. Firstly, we reproduce that item (which is on page 164 of Chess Explorations):

On page 30 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess Irving Chernev gives the queen odds game Potter v Amateur (London, 1870), in which ‘after only six moves were played, Potter announced a forced mate in nine!’ Chernev’s closing assertion: ‘Never before or since has a mate been announced which is longer than the rest of the game itself!’ See also page 75 of The Fireside Book of Chess for a similar remark.

Yet on page 2 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess the same Irving Chernev gives the score of Taylor v Amateur (London, 1862) in which, after Black’s fifth move, ‘White announced a forced mate in eight moves’. The game is introduced as follows: ‘The announcement of a forced win always comes as a shock to the victim. It is doubly so here, as the winning line of play is longer than the rest of the game itself!’ And on the following page he publishes the Potter game too.

Above is the position after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Bc4 Nxe4 4 Nc3 Nc5 5 Nxe5 f6 in the game Taylor v N.N.

White was I.O. Howard Taylor, who gave the diagrammed position on page 121 of his book Chess Brilliants (London, 1869) with the following text:

‘The diagram represents a quaint situation which happened to I.O.H.T. (White) on sitting down at the Philidorian Chess Rooms about February 1862, to play with a stranger (Black).

The fifth move only had been reached and the illustrious unknown had replied 5...P to KB’s 3rd. White thereupon mated in eight moves.’

The mating line, given by Taylor on page 128 (also without any reference to an announcement), corresponds to the moves in Chernev’s Best Short Games.

7565. Agnes Stevenson (C.N. 6548)

Agnes Stevenson (BCM, October 1925, page 407)

From Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina):

‘When was Agnes Stevenson born?

She married Rufus Stevenson in Hartlepool on 26 December 1912 according to the Familysearch.org website, which indicates that her full maiden name was Agnes Braveley Lawson.

However, that name does not appear elsewhere on the website, whereas there are several occurrences of Agnes Bradley Lawson (of Hartlepool), such as with the record of her baptism on 30 November 1873 (in Stranton, which is in West Hartlepool). Incidentally, her connection with West Hartlepool is well established in chess periodicals; see, for instance, page 322 of the July 1926 BCM.

A number of newspaper reports of her death, which occurred on 20 August 1935, mentioned her age as 52. See, for example, the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 23 August 1935, page 15. That, however, creates a discrepancy of ten years regarding her birth-date.

The same may be said of the age of Grace Alekhine, as show by a card at the Familysearch.org website, as well as a second one from the same source. Both give her date of birth as 26 October 1886 instead of 26 October 1876.’

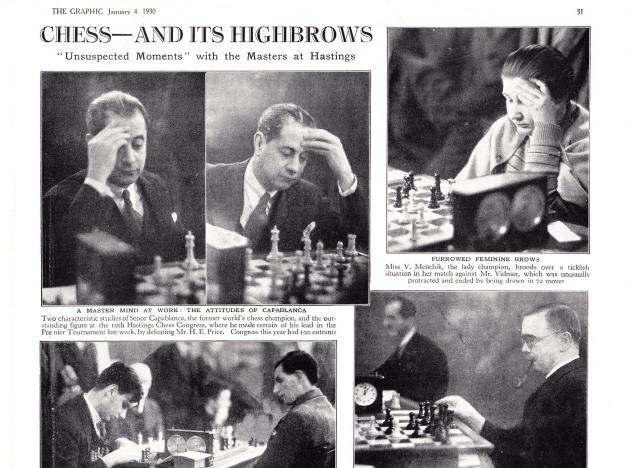

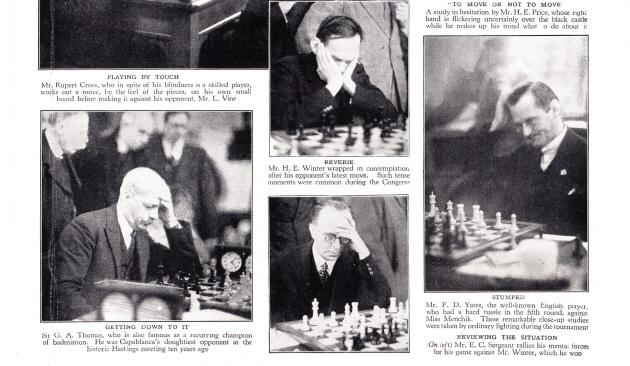

7566. Hastings, 1929-30

From our collection we reproduce page 31 of The Graphic, 4 January 1930:

A number of these photographs are in the February 1930 BCM.

7567. An Alekhine interview

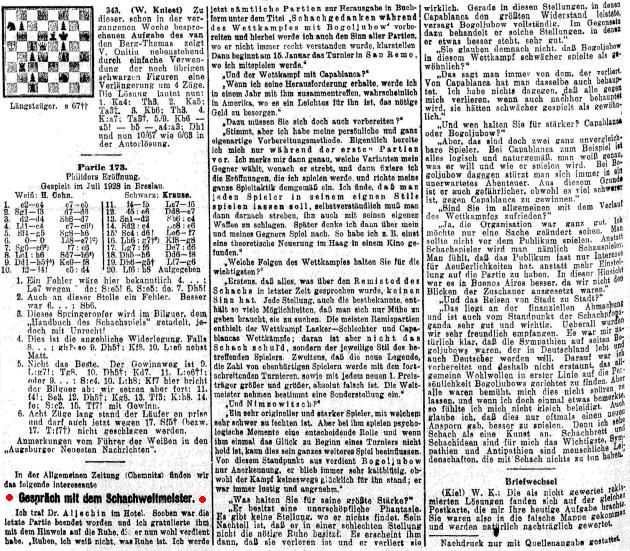

An interview with Alexander Alekhine shortly after his 1929 world championship match against Bogoljubow has been brought to our attention by Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany). It was published in the Allgemeine Zeitung (Chemnitz) and reprinted in the Aachener Anzeiger – Politisches Tageblatt of 30 November 1929:

Below is our translation:

‘Conversation with the world chess champion

I met Dr Alekhine in the hotel. The last game had just finished, and I congratulated him with the comment that he had now truly earned a rest.

‘A rest – I do not know what that is. I am now going to prepare all the games for publication in book form under the title “Chess Thoughts During the Match with Bogoljubow”, and I shall clarify the meaning of all the games, where it was not always understood correctly. Then on 15 January there begins the San Remo tournament, in which I am taking part.’

‘And the match with Capablanca?’

‘If I receive his challenge, I shall meet him in a year’s time, probably in America, where it is an easy matter for him to acquire the money necessary.’

‘For that too you need to prepare.’

‘That is true, but I have my personal and quite idiosyncratic method of preparing. Essentially, I prepare only during the first games. I note exactly which variations my opponent chooses, what he is striving for, and then I select the openings which I shall play and establish my entire tactics accordingly. I find that each player should be allowed to play in his own style, but it is naturally then necessary to try to defeat him with his own weapons. Later on, I think about my own play, and my opponent’s. To give an example, in The Hague on one occasion I found a theoretical novelty in a cinema.’

‘What do you regard as the most important consequences of the match?’

‘Firstly, that everything that has been said recently about the draw death in chess is senseless. Every position, and even the best known, contains so many possibilities that it is merely necessary to make the effort to look for them. The largest number of drawn games was in the Lasker v Schlechter match and in Capablanca’s matches; however, that is the fault not of chess but of the style of the players concerned. Secondly, that the new legend that, with the progression of tournaments and every new winner of a first prize, the number of evenly-matched players will become larger and larger is absolutely false. No doubt the world champions occupy a special position.’

‘And Nimzowitsch?’

‘A very original and strong player with whom it is very difficult to do battle. However, for him psychological moments play a decisive role, and if fortune does not smile on him at the start of a tournament, this can affect his entire subsequent play. From that standpoint, Bogoljubow merits only respect, for he always remained very cool-blooded even if the situation in the battle was by no means fortunate for him. He was always cheerful and pleasant.’

‘What do you consider to be his greatest strengths?’

‘He possesses inexhaustible fantasy. There is no position where he finds nothing. His disadvantage is that in a bad position he does not have the necessary calm. It then seems to him that the position is lost, and he does indeed lose. Precisely in the positions where Capablanca managed to put up the greatest resistance, Bogoljubow breaks down completely. In contrast, he handles very well positions in which he stands somewhat better.’

‘So you do not believe that Bogoljubow played more weakly in this match than usual?’

‘That is what is always said about the player who loses. The same was also asserted about Capablanca. I have nothing against everyone losing against me even if afterwards it is claimed that they played more weakly than usual.’

‘Whom do you consider stronger? Capablanca or Bogoljubow?’

‘Oh no, it is really not possible to compare the two players. With Capablanca, for instance, everything is logical and natural. One knows exactly what he wants and how he will play. With Bogoljubow, though, it is always a case of being hurled into an unexpected adventure. On that account he is also more dangerous, although it is much more difficult to win against Capablanca.’

‘Are you satisfied overall with the course of the match?’

‘Yes, the organization was quite good. There is just one thing that I should like to see changed. The games should not be played in public. Instead of a chessplayer, one becomes a performer. The impression given is that the public is more or less interested only in outward appearances, instead of focussing on the game. In this respect it was better in Buenos Aires, as we were not exposed to the eyes of spectators.’

‘And travelling from city to city?’

‘That was because of the financial agreement, and from the standpoint of chess publicity it is very good and important. Wherever we went, we received a very friendly welcome. It was obvious to me that the sympathies lay with Bogoljubow, who lives in Germany and wants to become German. I was prepared for that and was therefore not surprised that general goodwill was primarily directed at Bogoljubow’s personality. But everyone was at pains not to give any such impression, and if I ever noticed anything I did not feel offended. I also think that this often gave me a fresh incentive to play better. I regard chess as an art. For me, the chess board and chess ideas are the most important thing. Sympathy and antipathy are human passions which have nothing to do with chess.’

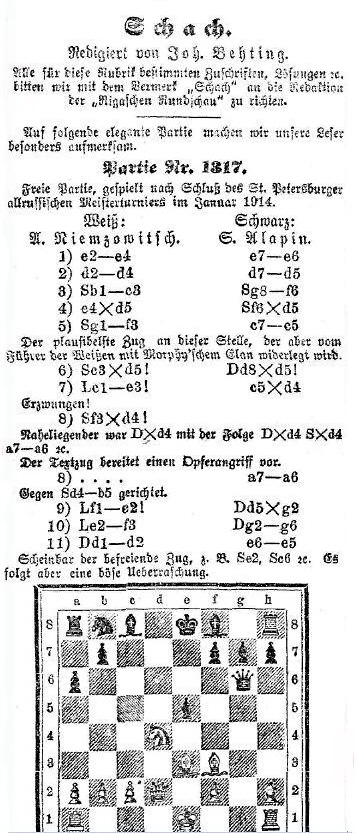

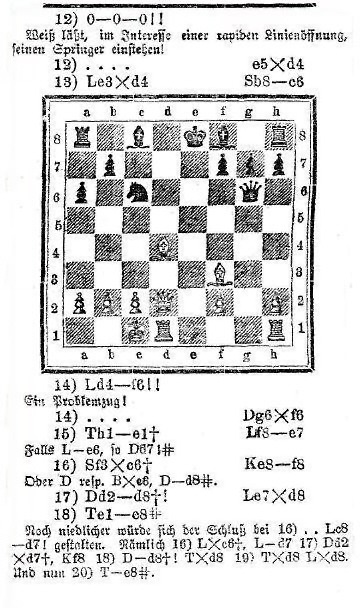

7568. Nimzowitsch v Alapin (C.N.s 6784, 6789, 6799, 6822 & 6835)

Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark) submits J. Behting’s chess column on page 47 of the Rigasche Rundschau of 4 April 1914 (new style), which has Nimzowitsch’s notes to his win over Alapin:

Mr Skjoldager comments:

‘The introduction to the game reads: “Offhand game played after the conclusion of the St Petersburg All-Russian Masters’ Tournament in January [old style] 1914.” If it was indeed played after the tournament ended, that may have been February, and not January. It could have been after the play-off or after the main event. The last round of the tournament was on 30 January 1914, and Nimzowitsch’s two-game play-off match against Alekhine took place on 4 and 5 February (with two adjournments). These dates are in the new style.

Thus Nimzowitsch would say “January” because of the Julian calendar in use in Russia. However, I think that the game was more probably played at the beginning of February (Gregorian calendar) or, possibly, on 31 January, although Nimzowitsch played a long game on 30 January. All in all, “January” is uncertain.’

7569. Reinfeld book (C.N. 7547)

The photograph shown in C.N. 7547 seems not to have been used until the 1959 reprint of Reinfeld’s book How to Play Chess. Below is the front of the dust-jacket of the original 1954 edition, with a shot of the famous game in which Alexander defeated Bronstein at Hastings:

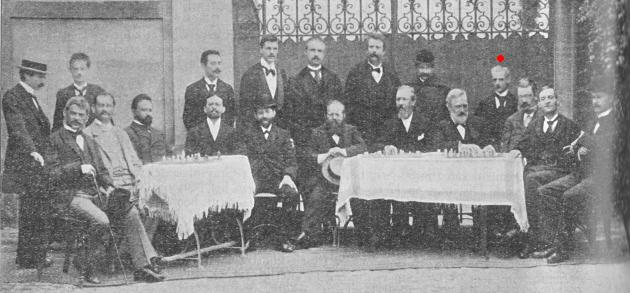

7570. Nuremberg, 1896

Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) notes that in addition to the familiar group photograph of Nuremberg, 1896 – published, for instance, opposite page 49 of Hundert Jahre Schachturniere by P. Feenstra Kuiper (Amsterdam, 1964) – a slightly different picture was on page 279 of Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond, November 1932:

Our correspondent remarks that the second photograph is relevant to the discussion on Carl Walbrodt’s height (C.N.s 5832 and 5913).

7571. Pillsbury in 1905

‘Chess Man Tries to Die’ was the headline of a report on page 2 of the Chicago Daily Tribune, 1 April 1905. Together with an account from the Philadelphia Record of the same date it has been added to Pillsbury’s Torment, courtesy of Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore).

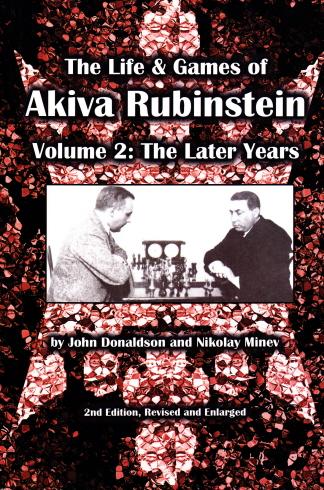

7572. Rubinstein book

From page 9 of volume two of The Life & Games of Akiva Rubinstein by John Donaldson and Nikolay Minev (Milford, 2011):

‘Rubinstein: 100 de sus mejores partidas recopiladas y una nota biográfica, authored by Jaime Baca-Arús and José Ricardo López, and published in Havana in 1922, has long been thought to be the first book to be published on Rubinstein but that is not in fact the case. John DeArman’s Rubinstein’s Games of Chess: A very incomplete collection of the match and tourney games of a great master was printed ten years earlier in Pasadena, California.

This has to be one of the rarest chess books in the world and it is quite possible the Los Angeles Public Library holds the only copy. The catalogue lists the book as 236 pages long, but actually this is only the number devoted to games; another 36 pages of flowery prose precede it. The book is a little smaller than the fourth edition of Modern Chess Openings, about 6½ by 4 inches (16.5cm x 10.2cm), but is packed with information. While DeArman has nothing original to offer he did do a first rate job of gathering information from many sources including the Deutsche Schachzeitung, the American Chess Bulletin and tournament books for many of the events Rubinstein played in ending in 1911.

This is not the only book that DeArman published. The Los Angeles Public Library also has his works on Nuremberg 1906, Hamburg 1910, San Sebastian 1911 and The Kings of Chess. The latter is an updated translation of a work by J. Rademacher (1905), published by DeArman in 1910, listing the tournament and match records of every master who has gained a prize in any international tournament. This is the only work of DeArman listed in the Cleveland Public Library catalogue for the John G. White collection.

The authors would be very interested in hearing from readers who have any information on DeArman, who is quite a mystery. His name does not produce any hits on Google nor did he play in any of the Northern California-Southern California chess matches between 1912 and 1926.’

7573. Who?

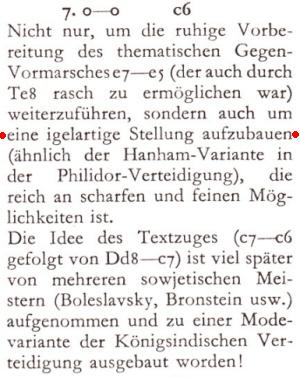

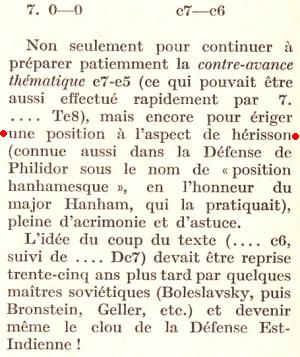

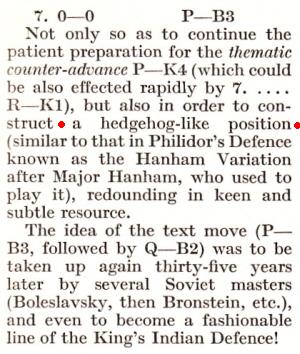

7574. The hedgehog formation

Mike Salter (Sydney, Australia) notes the comment after 7...c6 in Tartakower’s notes to his game against Speijer (St Petersburg, 1909) in Tartakowers Glanzpartien 1905-1930. The following is from page 45 of the second edition (Berlin and New York, 1986), after the moves 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 d6 3 b3 g6 4 Bb2 Bg7 5 e3 O-O 6 Be2 Nbd7 7 O-O c6:

We add below the note as it appeared on page 59 of Tartacover vous parle (Paris, 1953):

And from page 39 of Tartakower’s My Best Games of Chess 1905-1930 (London, 1953):

Mr Salter asks whether this is the first reference in

chess literature to a ‘hedgehog’ formation. Citations from

readers will be appreciated.

We note that on page 171 of the June 1951 Chess Review Tartakower annotated his win over Vidmar (Vienna, 1905). After 1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 Be2 g6 ...

... Tartakower commented:

‘The Dragon Variation was very popular in those days and was in fact a favorite weapon of my own. I had for example won some impressive games in the Hauptturnier at Barmen in 1905.

Some 15 years later, with the rise of the Hypermodern School, the less obvious merits of the Scheveningen Variation began to be appreciated. This line, which calls for 6...e6, is characterized by the position of the black pawns at e6 and d6 and gives the player of the black pieces a kind of “hedgehog” position.’

7575. Rude book reviews

C.N. 2613 (see page 391 of A Chess Omnibus)

quoted from page 43 of Chess World, 1 February

1950 C.J.S. Purdy’s comments on the book Chess Logic

For Beginner and Master by B. Koppin, which had been

published in the United States the previous year. Purdy

concluded:

‘It is well printed. But why was it printed?’

This is reminiscent of the parting shot in a review of G.H.D. Gossip’s The Chess Player’s Manual on pages 84-88 of the Westminster Papers, 1 September 1874:

‘In conclusion, we must mention the exterior of the book: paper and print are first-rate, but the merits of the publishers cannot compensate for the incapacity of the author.’

The review also remarked (on page 84):

‘The pages 27-34, containing the Laws of the British Chess Association, are the only pages in the book without blunders, at least blunders which can be attributed to the author.’

The following issue (1 October 1874, pages 105-106) of the Westminster Papers, which was edited by P.T. Duffy, related that a letter ‘of 11 closely written pages’ had been received from Gossip but that ‘we do not share with Mr Gossip the opinion that the public are expecting a reply from him’.

G.H. Diggle referred to the episode on pages 1-2 of the January 1969 BCM, in his article on Gossip, ‘The Master Who Never Was’:

‘This contemptuous and indeed unfair treatment would have flattened a man less courageous, and less wrong-headed, than its victim, especially as other reviews, though not so venomous, had been scarcely more favourable. Indeed, when the general chorus of groans had died down, it was thought that Gossip as an author had been disposed of for good. But suddenly in 1879 (after five years’ obscurity in the “doghouse”) he made a fighting recovery with The Theory of the Chess Openings ...’

7576. Caricature (C.N. 7549)

Another specimen, from page 3 of El Mundo Deportivo, 29 September 1929, has been supplied by Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France):

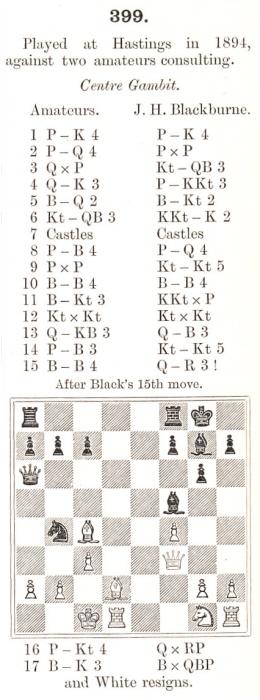

7577. Blackburne miniature

A famous brilliancy won by Blackburne:

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 Qxd4 Nc6 4 Qe3 g6 5 Bd2 Bg7 6 Nc3 Nge7 7 O-O-O O-O 8 f4 d5 9 exd5 Nb4 10 Bc4 Bf5 11 Bb3 Nexd5 12 Nxd5 Nxd5 13 Qf3 Qf6 14 c3 Nb4 15 Bc4

15...Qa6 16 g4 Qxa2 17 Be3 Bxc3 18 White resigns.

The game (‘played at Hastings in 1892’) is on page 176 of the P. Anderson Graham book Mr Blackburne’s Games at Chess (London, 1899), which identifies White as ‘Dr Colbourne’. The same appears in such popular books as Chernev’s 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (page 228). As so often, databases propose other spellings, such as Colburn and Kolborn.

Hastings had two chess figures, H. Colborne and J. Colborne, who were mentioned, for instance, as members of the Hastings, 1895 Committee on page xii of the tournament book. Nineteenth-century chess magazines include a number of references to a ‘Dr Colborne’ active in the Hastings area. He partnered Blackburne in a game against Gunsberg and Womersley, played in Hastings, which was published on pages 74-75 of the February 1894 BCM. Hastings was also the venue of a Vienna Gambit game which, partnered by Chapman, Dr Colborne lost to Blackburne (BCM, April 1895, pages 192-193). ‘Dr J.G. Colborne’ was mentioned on page 110 of the March 1898 BCM.

The Blackburne miniature is on pages 54-55 of Winning Quickly with Black by I. Neishtadt (London, 1996) as Allies v Blackburne, Hastings, 1894, with this footnote: ‘In some publications the game is given as being played in Bradford in 1901.’

However, the game is on page 142 of Chess Sparks by J.H. Ellis, a book published in 1895:

Tracing the game’s details and initial publication is more difficult than might be expected, although it was presented as a recent victory by Blackburne in Hastings against N.N. on page 50 of the February 1895 Deutsche Schachzeitung. Blackburne won the game against two amateurs according to pages 207-208 of the 15 July 1895 issue of La Stratégie (‘brillante partie jouée l’hiver dernier à Hastings’), its source being the Baltimore News. Readers’ assistance in finding other appearances of the game in nineteenth-century publications will be welcomed.

| First column | << previous | Archives [92] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.