Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [141] | next >> | Current column |

9829. Leading players

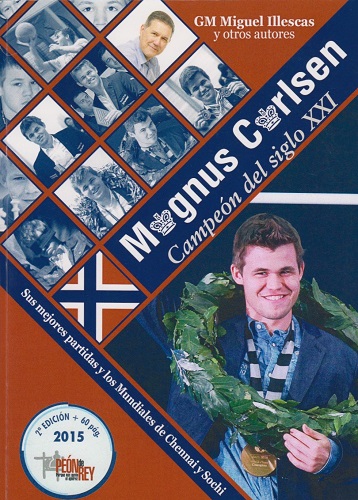

Books about Leading Modern Chessplayers now includes 15 volumes on Magnus Carlsen, as well as an entry for Sergey Karjakin which is currently a blank space.

C.N. 5113 remarked concerning Isidor Gunsberg: ‘He is the only world championship challenger on whom no book has been written.’

9830. Gunsberg and Steinitz

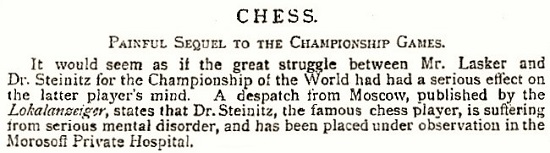

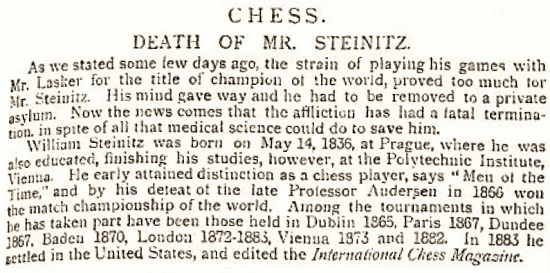

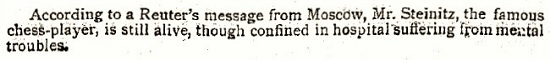

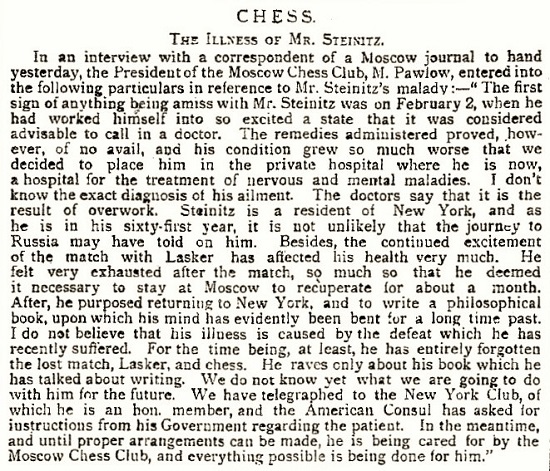

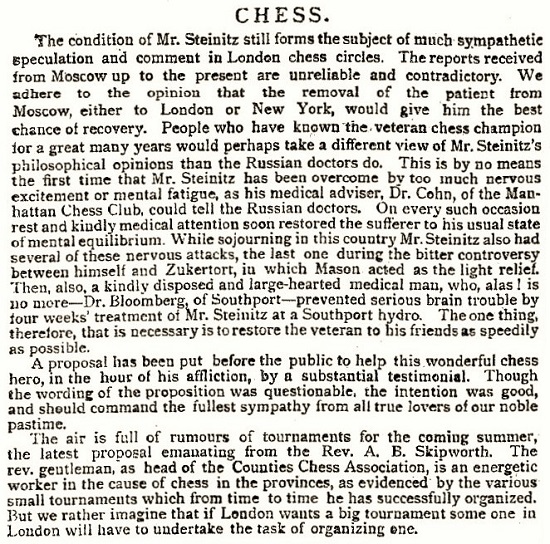

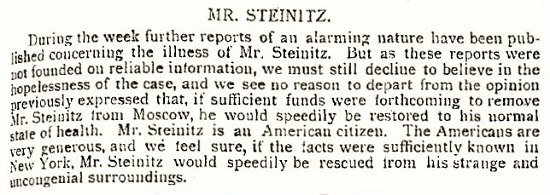

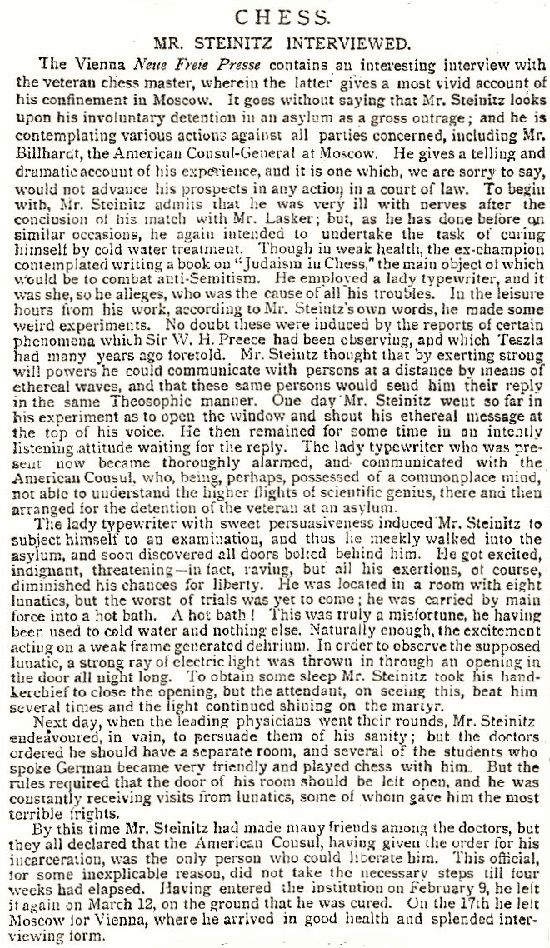

Gunsberg may also be the only person to write a premature obituary of a player against whom he contested a world title match. Below is a sequence of items in the Pall Mall Gazette, of which Gunsberg was the chess editor:

12 February 1897, page 9

22 February 1897, page 9

24 February 1897, page 9

26 February 1897, page 10

8 March 1897, page 10

15 March 1897, page 9

5 April 1897, page 10.

9831. Fischer, Capablanca and Golombek

Brian Karen (Levittown, NY, USA) asks for further information about Fischer’s view of Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1947).

C.N. 1928 (see our feature article on the book) alluded to Golombek’s remarks on pages 13-14 of The Games of Robert J. Fischer by Robert G. Wade and Kevin J. O’Connell (London, 1972). Below are his exact words:

‘I have written elsewhere (in my book on Capablanca’s games) of the apparent simplicity of Capablanca’s style which conceals a great deal of art. The same could well be said of most of the games of Bobby Fischer. He himself has acknowledged this influence and I remember some years ago in a recorded interview between him and Leonard Barden that was broadcast on a chess programme of the BBC how he said he had read and appreciated my book on Capablanca, thereby at once gratifying me as an author and confirming my already mentioned belief in the effect Capablanca had had on Fischer.’

C.N. 7987 quoted from pages 54-55 of My Seven Chess Prodigies by John W. Collins (New York, 1974):

‘In Bobby Fischer’s Chess Games, by Wade and O’Connell, contributing editor Sir [sic] Harry Golombek remarks on the influence of Capablanca on Bobby’s style and sees a strong resemblance in the respective strategies that run through their games. He recalls that Bobby acknowledged the influence in an interview with Leonard Barden that was broadcast on the BBC, and that Bobby also said he had read and appreciated a book on Capablanca by Golombek. The influence and resemblance are evident, and I have always been aware of it, recent evidence of it being in his third and fifth games with Spassky in Iceland. But I must say that I do not recall Bobby ever dwelling on his admiration of Capablanca or playing over great numbers of Capa’s games, though I assume he played over all of them at some time.’

Golombek also referred to the radio interview in his column (‘Fighting play of Bobby Fischer’) on page 11 of The Times, Weekend Features, 7 January 1967. After listing some of the American’s recent results, Golombek wrote:

‘All this, and much more, has been achieved by a style of play marked by deep yet clear positional strategy. It is significant in this respect that some years ago, in a radio interview, he said that he enjoyed playing over Capablanca’s games. A fighting player who is rarely content with a draw, Fischer produces game after game full of effective yet pleasing ideas. He is that rare combination, a player who thinks for himself and yet can learn from the practice of others.’

We have consulted Leonard Barden (London), but it is not possible to say whether the recording and/or transcript of his exchanges with Fischer have survived. At present, we can only quote from Mr Barden’s ‘Chess forum’ column in the Listener, 15 October 1964, page 607:

‘The 21-year-old United States champion Robert J. Fischer is undoubtedly the most controversial personality in present-day international chess. Listeners to the Third Network chess programmes will remember his forthright comments on other great masters when I interviewed him during the Leipzig Olympics in 1960 ...’

See too A Fischer Interview (responses to Román Torán’s questions in Leipzig) and Fischer’s Views on Chess Masters (his famous article on pages 56-61 of Chessworld, January-February 1964).

In an enthusiastic review of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975) Golombek wrote on page 10 of The Times (Saturday Review), 24 May 1975:

‘... my admiration for Capablanca’s style of play knows no bounds and my gratitude to the authors is correspondingly great.

... I, too, have spent many years studying the games of Capablanca and, nearly 30 years ago, published a book on him which, so I fondly hoped, would have helped to relieve the indigence of old age – an ever-present thought in the mind of a chess master.’

He made a further comment (in the third person) about his 1947 volume on page 354 of The Encyclopedia of Chess (London, 1977):

‘Capablanca was too lazy to annotate his later games. Golombek, a fervent admirer of his style of play, improved his own strength of play so much after studying Capablanca’s games that he won the British championship almost immediately after finishing the book.’

9832. Pillsbury

Information is requested concerning the above picture of H.N. Pillsbury, published on page 240 of the 1977 edition of Golombek’s The Encyclopedia of Chess. On page 360 it was credited to Lothar Schmid. (See too C.N. 7877.)

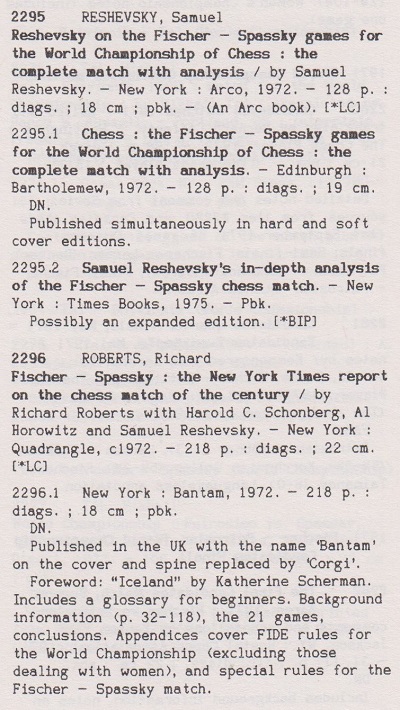

9833. Reshevsky on the 1972 world title match (C.N. 9812)

From page 196 of Chess An Annotated Bibliography 1969-1988 by Andy Lusis (London, 1991):

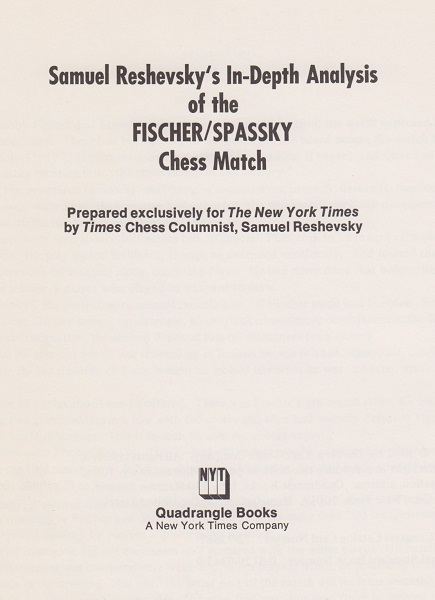

It is curious that Reshevsky had his name on the title page of three books on the Spassky v Fischer contest. The least familiar of them is Samuel Reshevsky’s In-Depth Analysis of the Fischer/Spassky Chess Match, and, contrary to the information (gleaned from Books in Print) in Lusis’ entry, it too was dated 1972. The title and imprint pages:

(The orange front cover had ‘Prepared exclusively for The New York Times and Bantam Books by Samuel Reshevsky’.)

The content is very similar – and often identical – to that of the well-known 128-page book published in New York and Edinburgh. Reshevsky’s Foreword is substantially different, and, for instance, page 3 of the Quadrangle Books, Inc. volume had the following:

‘Though the pre-match fireworks – cliff-hanging negotiations, protests, demands, postponements, disappearances – were more than anyone had expected, the title match itself fell disappointingly short of the titanic battle everyone looked forward to.

True, there were several excellent games but, in general, Fischer didn’t live up to the public’s expectations. His play lacked brilliance, though he defended excellently. And toward the end he surprised everyone by coasting along, accepting draws. He had never done that before; his reputation was that of a killer, a player who played to win, not to draw.

And Spassky? His performance seemed inexplicable. If Fischer made bad blunders, Spassky made incredible ones. In two games, for example, he overlooked one-move combinations; the first forced his immediate resignation, the second deprived him of all chances for a victory.’

The final paragraph nonetheless stated:

‘Still, despite the blunders, despite the general lack of brilliance, it was truly the chess match of the century, and the one that gave the United States its first formal world chess champion.’

How much of this was penned by Reshevsky is impossible to know, for the reasons set out in Chess and Ghostwriting.

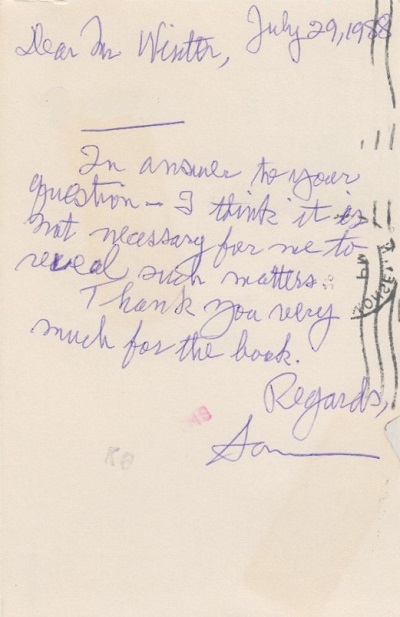

In a letter dated 23 July 1988 we asked Reshevsky about published suggestions that books of his had been ghostwritten, and he replied by postcard on 29 July 1988:

9834. Golombek on ghost-writing

From Harry Golombek’s column in The Times (Saturday Review), 29 October 1977, page 11, in a discussion of My Fifty Years of Chess by F.J. Marshall (New York, 1942):

‘I have been told he did not in fact write the book but that it was written for him. In any case one must assume that even if he did not actually write the work he told someone else what to write.

It is odd how this tradition of deputing other people to write one’s books seems to have flourished in America since Marshall was followed in this practice by two of the most outstanding of his successors as United States champion, Sammy Reshevsky and Bobby Fischer. It is also a little odd if indeed Marshall did descend to this practice since I gained the strong impression when I met him that he was one of the most honest and sincere of all grandmasters.’

Golombek’s further remarks about Marshall in that column were quoted in C.N. 5215.

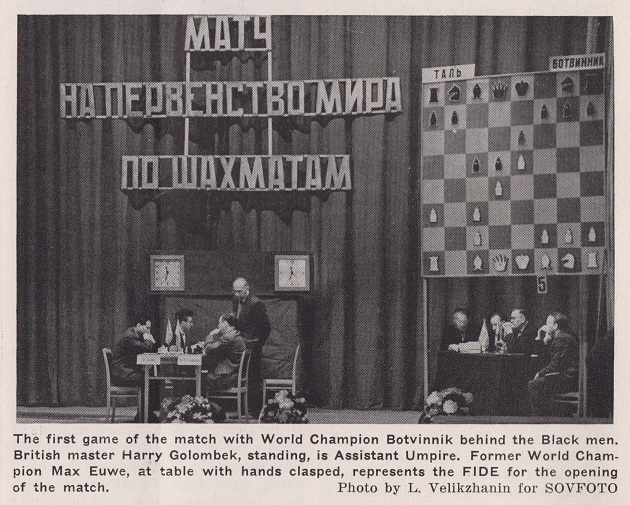

9835. Purdy v Golombek on Botvinnik v Tal

On page 29 of Chess World, February 1960 C.J.S. Purdy wrote:

‘If – we almost wrote “when” – Botvinnik loses the current match, he will have the right to a return match in 1961 ...

Tal seems generally favoured to beat Botvinnik. We think stamina will decide in Tal’s favour ...’

And from page 73 of the May 1960 issue:

‘This was the only world title match about which we have ever ventured a prophecy.’

On page 57 of the April 1960 Chess World Purdy criticized Harry Golombek, under the heading ‘Extraordinary Prediction’:

‘At that stage [after the short draw in the 13th match-game], with Tal two games ahead, Golombek published an extraordinary prediction that Botvinnik would hold his title. Golombek faces the alternative prospect of becoming known as either the greatest prophet or the greatest neck-out-sticker in chess history.

... One of the reasons that Golombek gives is that Botvinnik has a better knowledge than Tal of the openings that are being played! Here is logic to make poor old John Hanks writhe in agony. It would be just as sound to say one tennis player should beat another because his service is superior.

... Golombek’s writings all tend to show that he regards chess rather too much as a body of knowledge. If knowledge of the openings went far, Golombek himself would be one of the world’s best players.

Chess is primarily a skill. It’s mainly a matter of who sees the mostest the fastest. Tal sees the mostest the fastest of all. He would have done better still had he played more soberly after amassing a three-point lead.

Seeing the mostest the fastest is not the whole story. Petrosian may be Tal’s equal there. That is technique. After that comes the art of choosing between moves that technique ranks equal, or as possibly equal. Petrosian, like Capablanca, will always choose the calculable. Tal will often choose the incalculable. Such a player develops an intuition for chances. Tal’s intuition is not perfect, as we see from the ninth game, below, but many of his other games show that it is almost magical, all the same.

Golombek’s prediction may possibly come true, but the reasoning he bases it on is faulty. He seems to be a Botvinnik fanatic.’

It is unclear to us which particular text or texts by Golombek prompted Purdy’s remarks. Our reading of the game-by-game reports by Golombek from Moscow in the BCM and The Times is that he was even-handed and not remotely a ‘Botvinnik fanatic’.

Chess Review, May 1960, page 136

9836. Perhaps the most daring sacrifice

Black to move

In this position from the sixth match-game between Botvinnik and Tal (Moscow, 26 March 1960) Purdy wrote regarding 21...Nf4:

‘Perhaps the most daring sacrifice ever made in a world championship match, for the consequences were certainly not fully calculable. It is easy to see that Black gets two pawns for his piece, but White retains his two bishops and there is no crash on White’s king.’

Source: Chess World, March 1960, page 47.

9837. Did Lasker deliberately play badly? (C.N. 9684)

An observation by Purdy on page 43 of the March 1960 Chess World:

‘I have never believed that Lasker played designedly bad moves in the opening. I think he played designedly rapid moves – to conserve time – and it naturally turned out fairly often that they were not the best. And he would vary from “the book” if he thought a move had a good chance of turning out just about as good as the “book” move.’

9838. Chess play and chess history (C.N. 9487)

The present sequence of Purdy items ends with a paragraph by him about Réti’s Masters of the Chess Board, on page 20 of Chess World, January 1960:

‘How many chess books do players as a rule go through from cover to cover? Not many. This is one. Réti’s idea was that the chessplayer should go through the same evolution as chess theory itself – first learn the Anderssen and Morphy way, then learn what Steinitz added, then Tarrasch and so on up to modern times. He was right. He also knew that most players want moves really explained – not strings of analysis. For all except very advanced players, Masters of the Chess Board is a really wonderful book.’

9839. A curious Kasparov ‘autobiography’

Following information received from Miquel Artigas (Sabadell, Spain), we have acquired Chamo-me ... Garry Kasparov (Lisbon, 2011), as well as the translations into Spanish and Catalan, Me llamo ... Garri Kasparov (Badalona, 2013) and Em dic ... Garri Kasparov (Badalona, 2013).

Intended for children aged nine and over, the 64-page book was written by Manuel Margarido and illustrated by Manuel Alves. It is part of an extensive series of imaginary autobiographies:

The principal sources for the Kasparov text are loose talk from the Internet (including, on pages 15-16, ‘it is calculated that more than 600 million people throughout the world play chess’) and his own books, which are sometimes no less loose. The section on ‘My books’ refers to the atrocious (our word, and not Margarido’s or Kasparov’s) Child of Change and to the first volume of My Great Predecessors. The latter book, abysmal in terms of history and scholarship, is described on page 47 as merely containing ‘some errors, later corrected’. Would that they had been.

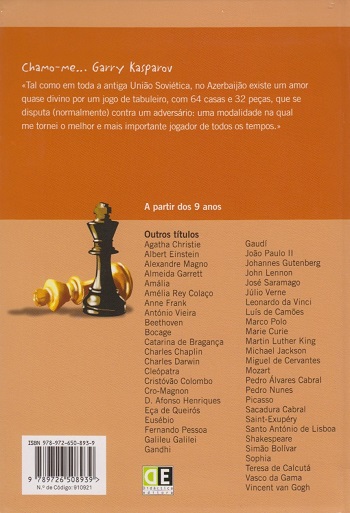

Kasparov’s political/agitatorial activities are covered too, as shown by pages 54-55:

The front and back covers have Kasparov affirming that he was the best chessplayer of all time, whereas the book’s text puts slightly more cautious words in his mouth. From page 44:

‘Para muitos, como te disse, fui o melhor jogador de xadrez de todos os tempos. Já me conheces e sabes que não vou negar essa opinião.’

Many respectable authorities have called Kasparov the greatest player in the game’s history, but how close has he himself ever come to making such a claim?

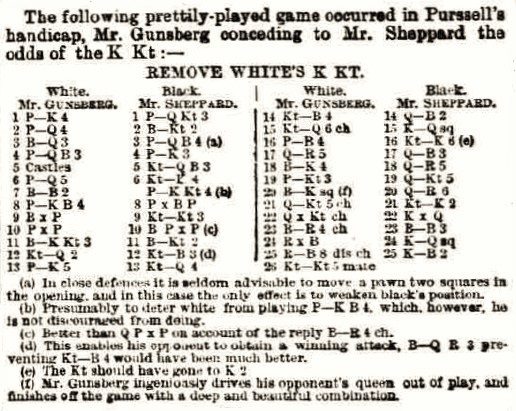

9840. Gunsberg v Sheppard

From page 2 of the Morning Post, 6 April 1886:

(Remove White’s king’s knight.) 1 e4 b6 2 d4 Bb7 3 Bd3 c5 4 c3 e6 5 O-O Nc6 6 d5 Ne5 7 Bc2 g5 8 f4 gxf4 9 Bxf4 Ng6 10 dxe6 fxe6 11 Bg3 Bg7 12 Nd2 Nf6 13 e5 Nd5 14 Nc4 Qc7 15 Nd6+ Kd8 16 c4 Ne3 17 Qh5 Qc6 18 Be4 Qa4 19 b3 Qb4 20 Be1 Qa3 21 Qg5+ Ne7

22 Qxe7+ Kxe7 23 Bh4+ Bf6 24 Rxf6 Kd8 25 Rf8+ Kc7 26 Nb5 mate.

The newspaper’s notes were reproduced on pages 463-464 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 7 April 1886, and a news report on page 457 of the same issue of the magazine stated:

‘A handicap tournament which has been in progress for some time past at Purssell’s restaurant, EC, has resulted in favour of Mr Gunsberg. Mr Fenton, who received the odds of pawn and two moves from the winner, was second.’

9841. Munich, 1936 and Maróczy

An addition to The 1936 Munich Chess Olympiad is this photograph on page 60 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 1 April 1940:

An autobiographical note by Maróczy was on page 69 of the 1 May 1940 issue:

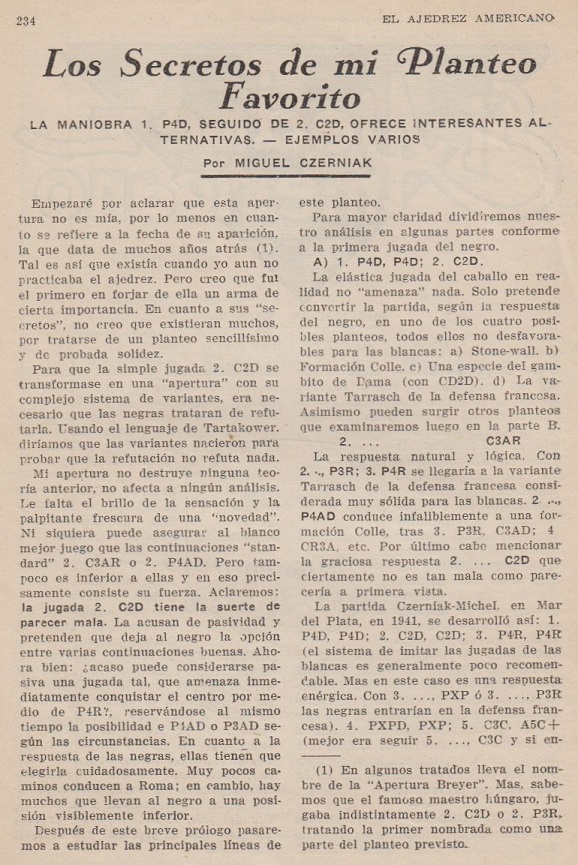

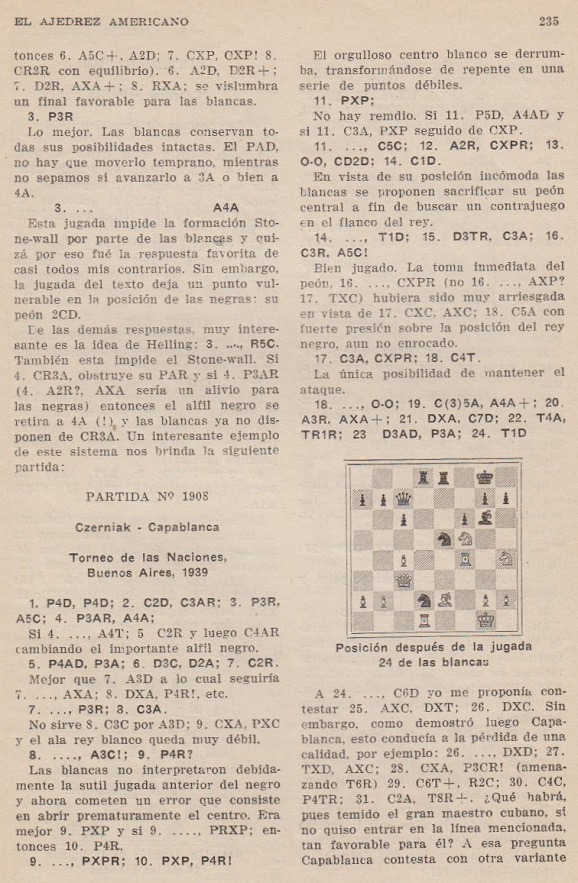

9842. Czerniak v Capablanca

Page 284 of our book on Capablanca gave his comments on the game which he drew as Black against M. Czerniak in the 1939 International Team Tournament in Buenos Aires, and C.N. 4143 had further information and a photograph.

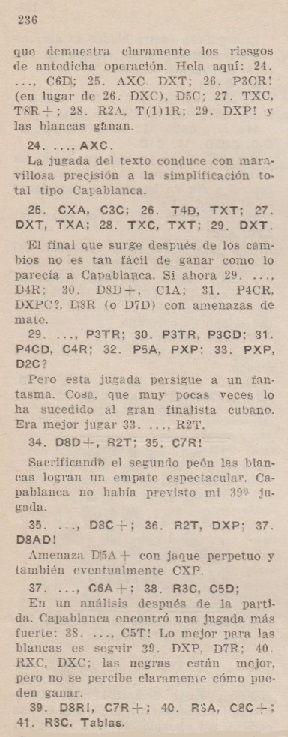

The moves: 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nd2 d5 [As shown below, in 1943 Czerniak gave 1 d4 d5 2 Nd2 Nf6.] 3 e3 Bg4 4 f3 Bf5 5 c4 c6 6 Qb3 Qc7 7 Ne2 e6 8 Nc3 Bg6 9 e4 dxe4 10 fxe4 e5 11 dxe5 Ng4 12 Be2 Nxe5 13 O-O Nbd7 14 Nd1 Rd8 15 Qh3 Nf6 16 Ne3 Bb4 17 Nf3 Nxe4 18 Nh4 O-O 19 Nef5 Bc5+ 20 Be3 Bxe3+ 21 Qxe3 Nd2 22 Rf4 Rfe8 23 Qc3 f6 24 Rd1 Bxf5 25 Nxf5 Ng6 26 Rd4 Rxd4 27 Qxd4 Rxe2 28 Rxd2 Rxd2 29 Qxd2 h6 30 h3 b6 31 b4 Ne5 32 c5 bxc5 33 bxc5 Qb7 34 Qd8+ Kh7 35 Ne7 Qb1+ 36 Kh2 Qxa2 37 Qc8 Nf3+ 38 Kg3 Nd4 39 Qe8 Ne2+ 40 Kf3 Ng1+ 41 Kg3 [Ne2+ 42 Kf3] Drawn.

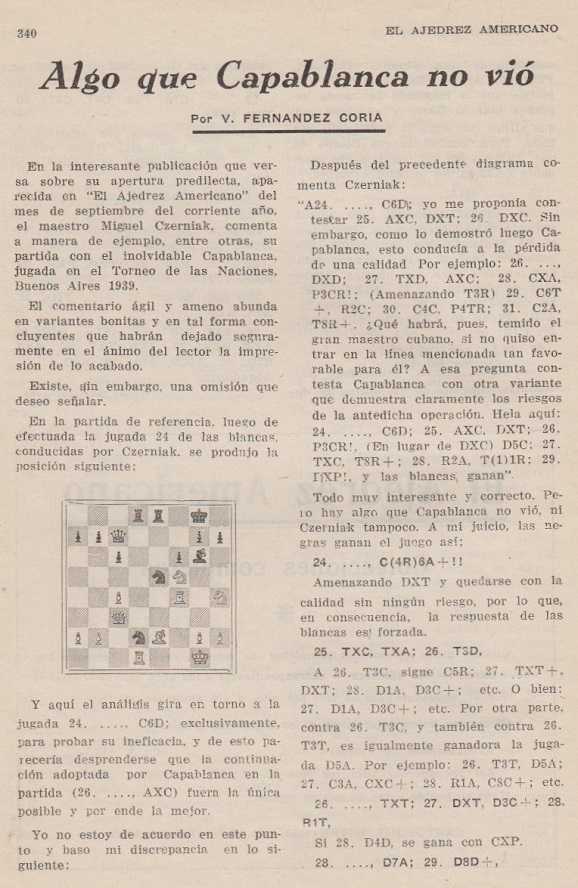

Czerniak annotated the game on pages 234-236 of El Ajedrez Americano, September 1943:

A follow-up analytical article was contributed by V. Fernández Coria on pages 340-341 of the December 1943 issue of the Argentinian magazine:

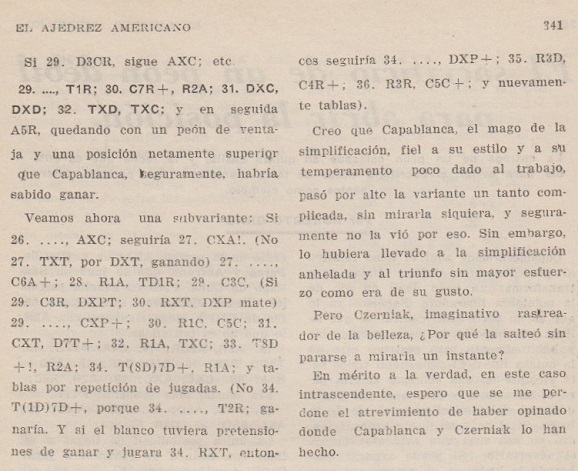

Czerniak also discussed the conclusion in his book El final. Below is what appeared (with a misprinted date) on page 229 of the third edition (Buenos Aires, 1959):

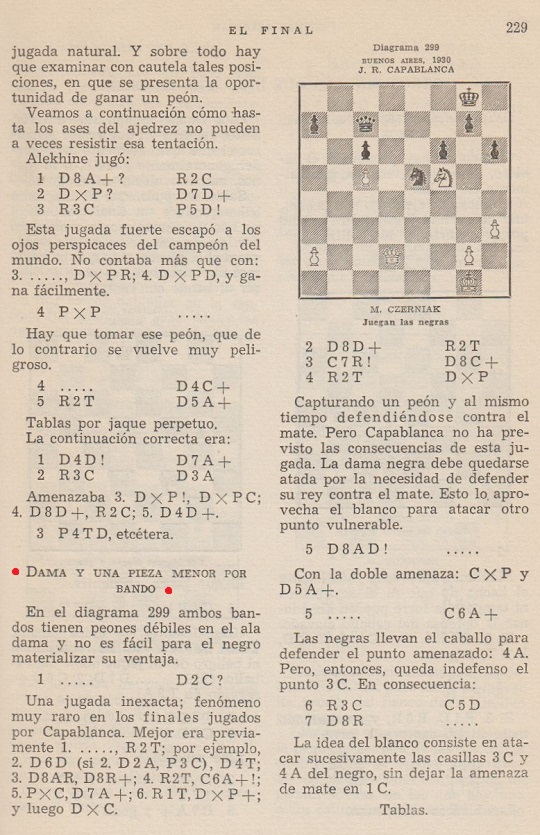

9843. Capablanca and Znosko-Borovsky

C.N. 2032 (see page 274 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves and Chess Anecdotes) discussed the old story about Capablanca and Znosko-Borovsky writing, or talking about writing, books on each other’s play.

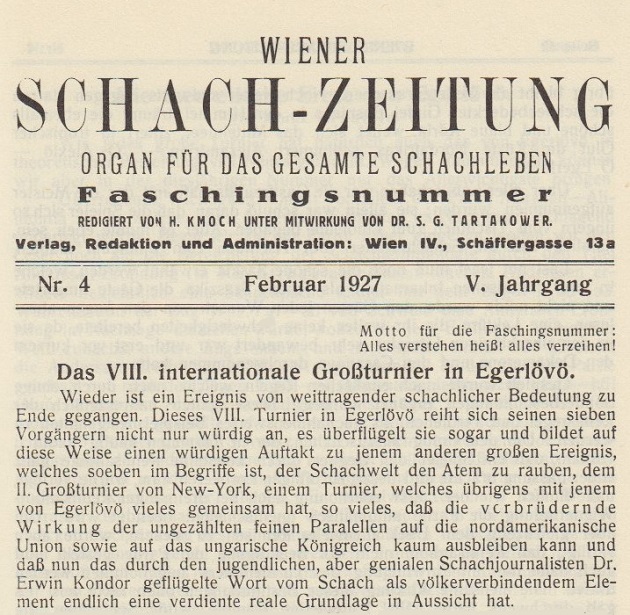

From page 54 of the February 1927 Wiener Schachzeitung:

That was in a spoof issue (4/1927), comprising jokes and parodies. See C.N. 6452 for another example, concerning Alekhine.

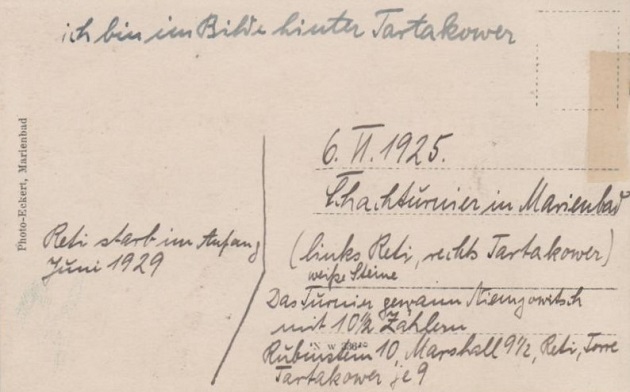

9844. Marienbad, 1925

Michel Benoit (Champs-sur-Marne, France) has forwarded this postcard (Réti v Nimzowitsch, Marienbad, 1925):

Our correspondent notes the unidentified writer’s reference to ‘Tartakower’ in the top line. For purposes of comparison, below is a better version of the Marienbad, 1925 group photograph on page 8 of the 7 June 1925 Wiener Bilder which was in C.N. 5119, with information added in C.N. 5125:

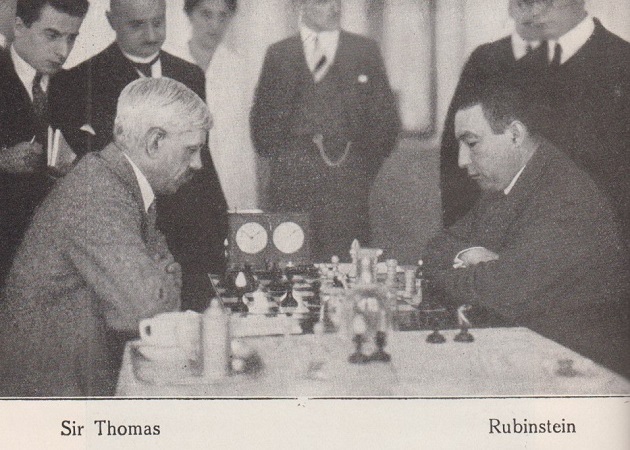

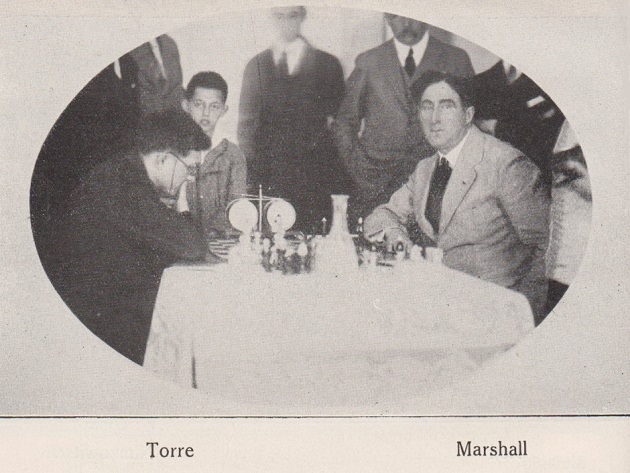

The tournament book included the above two photographs, as well as these:

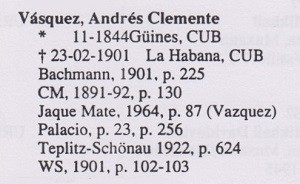

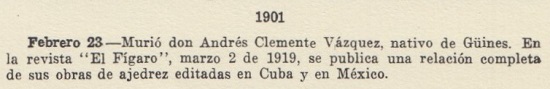

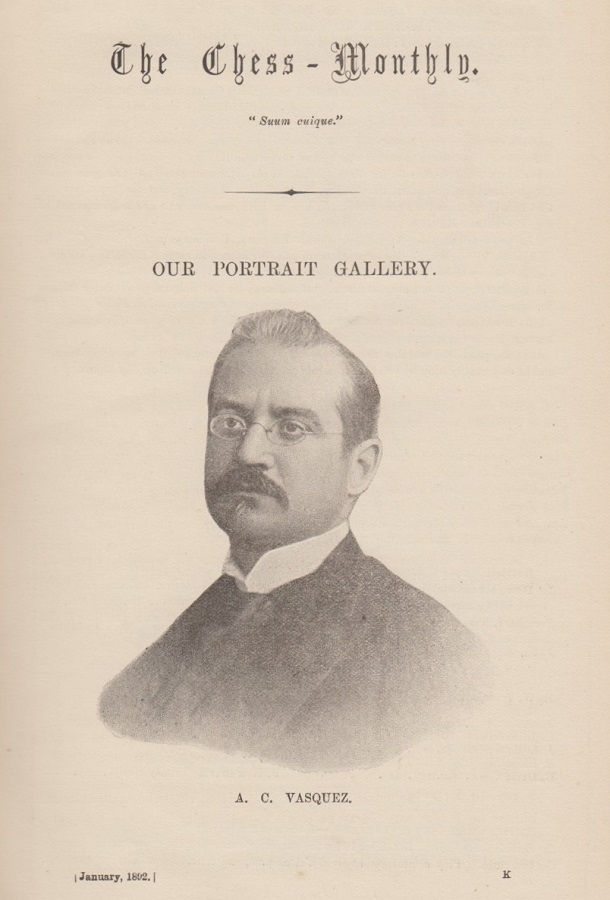

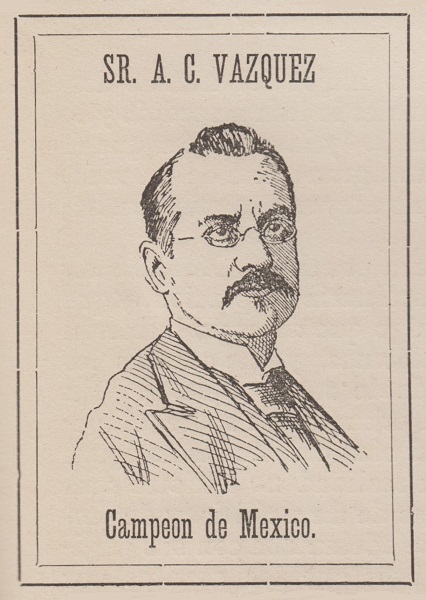

9845. A.C. Vázquez

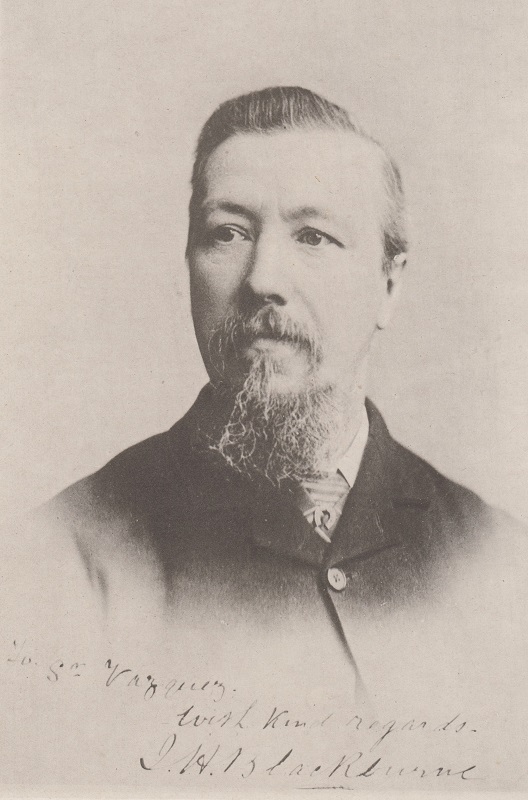

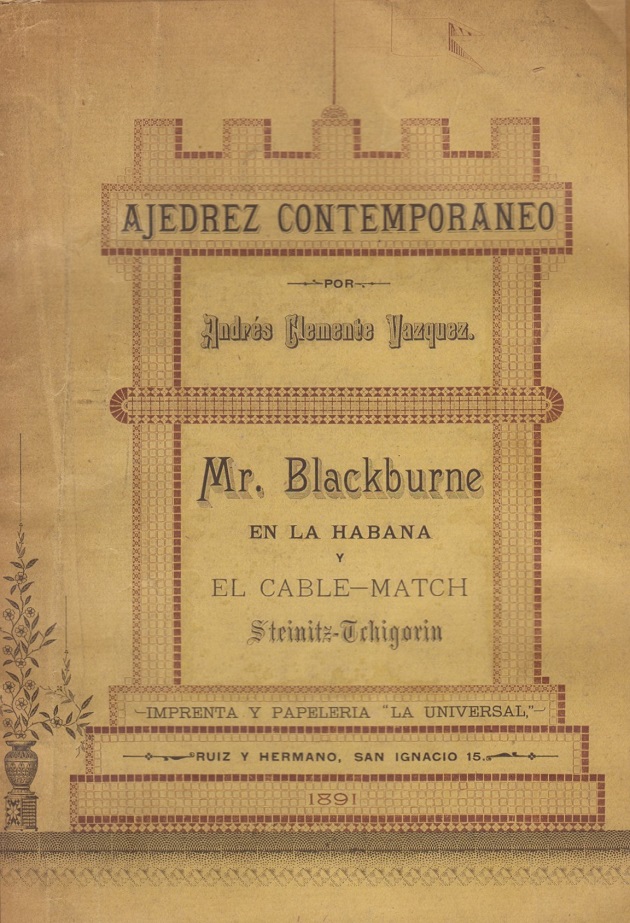

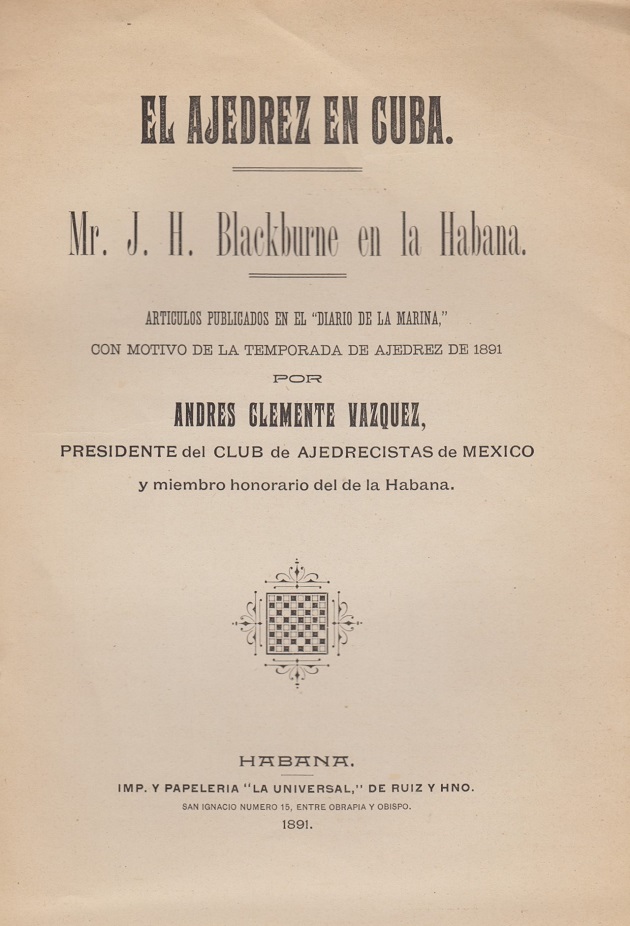

Photographs inscribed by one master to another are scarce. Below is the frontispiece of an 1891 book by Andrés Clemente Vázquez:

The photograph was reproduced on page 309 of Joseph Henry Blackburne. A Chess Biography by Tim Harding (Jefferson, 2015), but with the inscription chopped off.

Vázquez’s book shows the difficulties facing writers and bibliographers who seek precision. Surprisingly often, there is a disparity between a volume’s title on a) the front cover or dust-jacket and b) the title page. In such cases, we consider it preferable to use the latter, but the two may be entirely different:

A writer who opts for the front-cover version, the easier solution in this instance, needs to bear in mind that the word contemporáneo takes an acute accent. So, usually, does the name Vázquez, e.g. in other books by him. (Authors, publishers and websites reveal much about themselves by their attention or indifference to accents.)

An oddity is the frequency with which the spelling ‘Vásquez’ or ‘Vasquez’ is seen. For example, ‘Vasquez’ occurs twice in the last paragraph of chapter one of Capablanca’s My Chess Career (London, 1920). ‘Vásquez’ was favoured by Jeremy Gaige, as shown by the entry in his unpublished 1994 edition of Chess Personalia:

However, the above-mentioned material on pages 23 and 256 of Ajedrez en Cuba by Carlos A. Palacio (Havana, 1960) had ‘Vázquez’:

C.N. 7036 gave a picture of Vázquez, and another illustration is shown below:

Finally, from page 35 of his 1891 book:

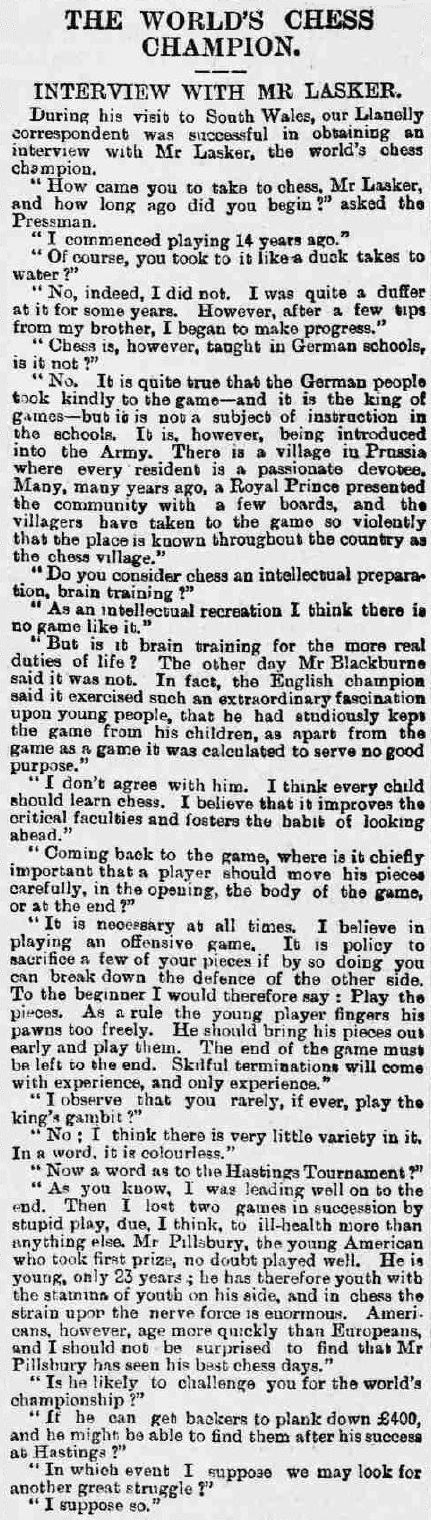

9846. An interview with Emanuel Lasker

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found an interview with Lasker on page 3 of the South Wales Daily News, 15 November 1895:

9847. Wormald and Worrall

From Achim Engelhart (Illerkirchberg, Germany):

‘After 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 many sources, such as pages 451 and 471-472 of Hooper and Whyld’s Oxford Companion to Chess (Oxford, 1992), distinguish between:

5 Qe2 as the “Wormald Variation”, and

5 O-O Be7 6 Qe2 as the “Worrall Attack”.

The naming of 5 O-O Be7 6 Qe2 as the “Worrall Attack” appears to originate from S. Tartakower, based on confusion of the similar names of T.H. Worrall (1807-78) and R.B. Wormald (1834-76, who was discussed in C.N. 3974), in an article in L’Echiquier November-December 1931, pages 1493-1496. Tartakower called both 5 Qe2 and 5 O-O Be7 6 Qe2 “L’attaque Worall” [sic], and on page 1494 he wrote, after 6 Qe2:

“Voilà!! Ce coup, introduit par Worall et analysé par Alapine, très volontiers appliqué, du reste, par les maîtres anglais Sir Thomas et Yates ...”

Given that Tartakower quoted Schlechter’s analysis (from page 498 of the Handbuch des Schachspiels, eighth edition, 1916, where 5 O-O Be7 6 Qe2 was given no name), it is likely that he simply misread the remark on page 492 about Wormald’s recommendation 5 Qe2:

“Dieser Zug, der schon von Wormald, Chess World II, S. 280 empfohlen wurde, ist bei weitem nicht so stark als 5 O-O und deshalb in der Praxis wenig gebräuchlich. In den letzten Turnieren hat ihn Alapin wieder mehrfach versucht.”

Later sources (starting with page 230 of the fifth edition of Modern Chess Openings, in 1932) attached the name “Worrall Attack” solely to 5 O-O Be7 6 Qe2, thereby cementing Tartakower’s error. It thus seems that T.H. Worrall had nothing to do with either of the variations, whereas the actual inventor, R.B. Wormald, played at least one game with 5 O-O Be7 6 Qe2 (against C. De Vere in the Glowworm Tourney, London, 1868). It was published on pages 369-370 of the 10/1868 issue of Chess World.’

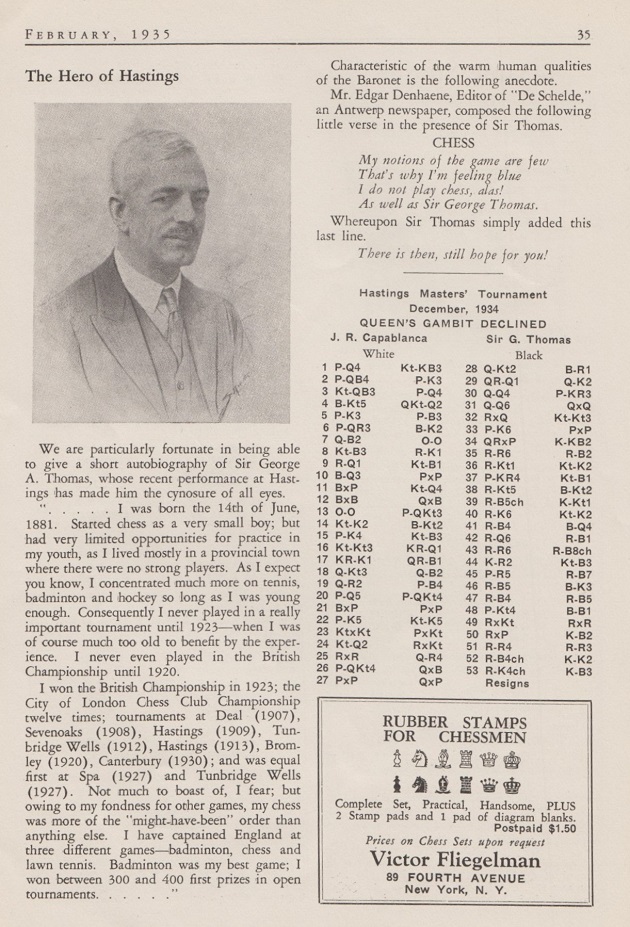

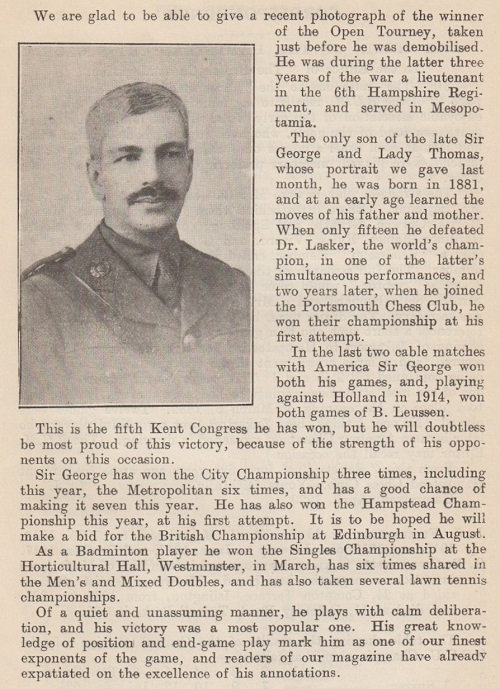

9848. ‘Sir Thomas’

C.N.s 9844 and 9847 both had ‘Sir Thomas’, a common ‘Sir plus surname’ error referred to in Chaos in a Miniature.

‘Sir George A. Thomas’, ‘Sir Thomas’, ‘Sir George Thomas’ and ‘Sir G. Thomas’ all appeared on page 35 of the February 1935 Chess Review:

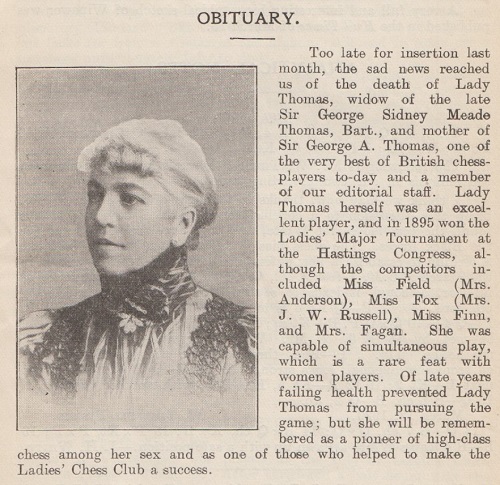

The autobiographical note was given in C.N. 7088. Another item about Sir George comes from page 133 of the May 1920 BCM:

From page 99 of the April 1920 BCM:

Further information about Lady Thomas was provided in C.N. 5690. Her husband died in 1918, and the National Portrait Gallery, London has a fine photograph of their son.

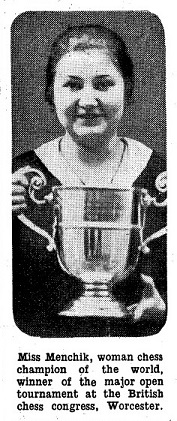

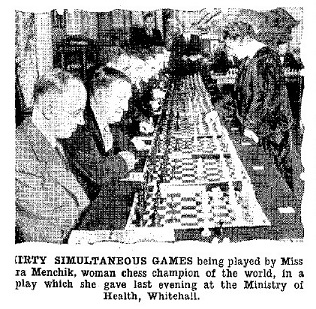

9849. Vera Menchik

This photograph comes from page 49 of Famous Chess Players by Peter Morris Lerner (Minneapolis, 1973):

The caption on the previous page stated that the picture was taking during a 20-board simultaneous display in London in 1931. According to page 24 of the Daily Mirror, 7 February 1931, which also printed the photograph, the exhibition took place on 6 February.

Two other photographs from the same newspaper are reproduced below. Can good-quality copies be found?

Daily Mirror, 24 August 1931, page 20

Daily Mirror, 17 April 1935, page 17.

9850. Photographs of Rubinstein in Palestine

Harvard Library’s HOLLIS+ collection has photographs of A. Rubinstein in Tel Aviv in 1931, during a simultaneous exhibition (one of his opponents being Hayim Nahman Bialik) and a game of living chess.

The site also has hundreds of shots taken during the 1964 Olympiad in Tel Aviv.

9851. Czerniak v Capablanca (C.N. 9842)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) points out that the conclusion of the Czerniak v Capablanca game was on page 223 of the first edition of Czerniak’s El final (Buenos Aires, 1941), with the correct date (1939) and a few minor textual differences.

9852. Kasparov on Kasparov (C.N. 9839)

Adam Ponting (Petersham, Australia) notes a ChessBase article dated 5 April 2005 in which one of the questions posed to Kasparov by Mig Greengard and Dylan Loeb McClain, ‘Where would you rank yourself all-time?’, was answered as follows:

‘I don’t like this question in general, it’s too subjective. By most standards, number one because of the length of my high performance and the strength of the opposition. The greatest gap between the number one and the rest was Bobby Fischer in 1972, but that was just one or two years and then came Karpov. I was able to keep up with the new generation and beat them. I was able to stay on the cutting edge, stay on top of the ranking for 20 years. I would say that entitles me to be number one.’

9853. The art of citation

From page 178 of Yearbook of Chess Wisdom by Peter Zhdanov (Niepołomice, 2015):

9854. Rubinstein in Palestine (C.N. 9850)

Regarding the second photograph referred to in C.N. 9850, Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) draws attention to two pages on his Jewish Chess History website. They offer information about (1) the venue of the game of living chess between A. Rubinstein and M. Marmosh (the Ha’Poel football ground in Tel Aviv, on 9 May 1931) and (2) Emanuel (Emanueli) Luftglas, who designed the costumes.

See too the ‘Rubinstein in Palestine’ section on pages 368-371 of volume two of The Life & Games of Akiva Rubinstein by John Donaldson and Nikolay Minev (Milford, 2011).

9855. The Giuoco Pianissimo (C.N. 9808)

An article entitled ‘Analytical Excursions’ by J.H. Zukertort on pages 4-6 of the City of London Chess Magazine, February 1874 examined the Giuoco Piano. After 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 Zukertort wrote:

‘A very weak continuation is 5 P to Q3, which Anderssen calls, in jest, giuoco pianissimo.’

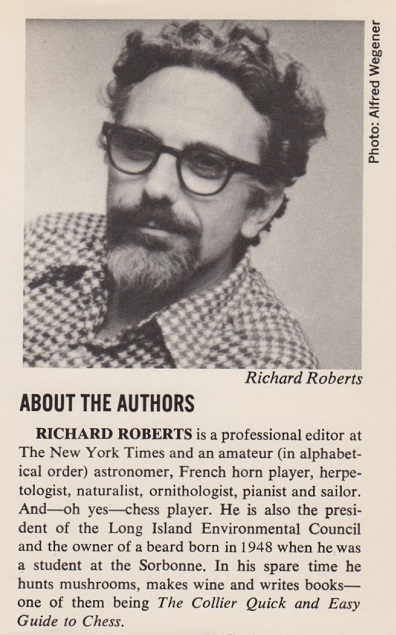

9856. Richard Roberts

The dust-jacket of Fischer/Spassky: The New York Times Report on the Chess Match of the Century by Richard Roberts, with Harold C. Schonberg, Al Horowitz and Samuel Reshevsky (New York, 1972) had this note on Richard Roberts:

The front cover of The Collier Quick and Easy Guide to Chess (New York, 1962) included the following:

Which are the ‘several books on chess’ edited by him?

9857. Resignation

Chess literature is awash with claims that Tartakower ‘once’ wrote that nobody ever won a game by resigning, but never once have we found proof.

The matter was raised by Daniel King (London) in C.N. 2356 and discussed in C.N. 3374 (see page 345 of A Chess Omnibus and page 337 of Chess Facts and Fables). The latter item quoted the following from page 121 of Tartakower’s Die Hypermoderne Schachpartie (Vienna, 1924), in a note to Black’s 33rd move in Maróczy v Chajes, Carlsbad, 1923:

‘Der transatlantische Meister Chajes steht auf dem Standpunkt, dass man durch das Aufgeben noch keine Partie gerettet hat.’

We commented in C.N. 3374:

This may be translated as ‘The transatlantic master Chajes is of the view that no player has ever saved a game by resigning’, it being unclear whether Tartakower was suggesting that Chajes himself had made the remark in question.

9858. The post mortem

From page 35 of Chess Quotations from the Masters by Henry Hunvald (Mount Vernon, 1972):

The observation was in an unsigned article, ‘The Chess Championship’, on page 17 of The Times, 19 October 1937. The paragraph in question:

‘Chess above all other games lends itself to the post mortem. It is not even necessary to have seen the pieces moved to be able to lay down exactly what the pundits have done wrong. Moreover, the critic, unhampered by the “touch-and-move” rule and the ruthless ticking of the chess-clock, is quite likely to be right. So in clubs and cafés where this [sic] peculiar people foregather there is frantic brandishing of pocket-boards, dog-eared newspaper cuttings are thumbed again and again, and neglected eggs congeal in their own poached blood as passionate partisans proclaim, “he should have fianchettoed his bishop”, to be answered with, “if he had, White would have opened the rook’s file and established his passed pawn”. For every move there is eager canvassing of a dozen positions that might have been, but were not, evolved; and, after the storm and stress of debate has subsided, the “scores” will be at last laid up in the reference books of chess, together with a wealth of minute comment more elaborate than is bestowed on any other text except Holy Writ.’

The full article, written after six games had been played in the Euwe v Alekhine world title match, was reproduced on page 247 of the November 1937 Chess Review with this comment by Fred Reinfeld:

‘The article is remarkable for its expert knowledge of current trends in chess, as well as for its delightfully whimsical character ...’

At the end of the page Reinfeld added:

‘With the honorable exception of the New York Times, the American press is heavily unaware of the match, giving it less space than a spelling bee in Hackensack, a marbles championship on the East Side, or a boy scout jamboree is Oscawana.

The wretchedly skimpy treatment of the championship match in the American press presents a lamentable contrast to the very full and expert coverage in the Dutch press.’

9859. Pawn sacrifices

Wanted: early references to pawn offers being the best or hardest type of chess sacrifice.

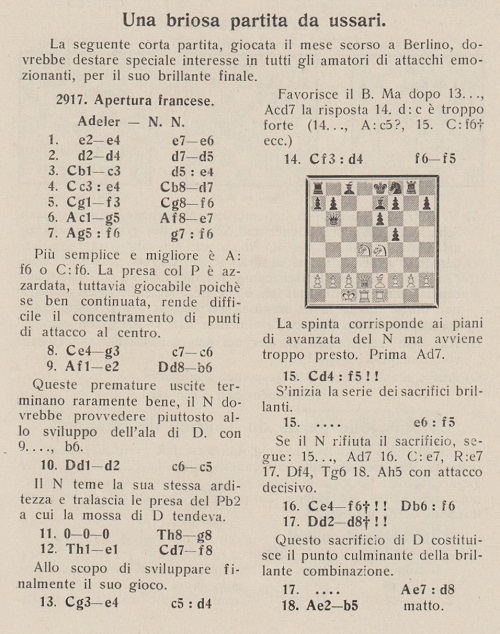

An example (‘Pawn sacrifices are the finest sacrifices after all’) comes from A. Becker’s notes to Réti v Tartakower, Hastings, 31 December 1926, on pages 2-4 of the January 1927 Wiener Schachzeitung. 1 Nf3 Nf6 2 d4 d5 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 Be7 5 Bg5 h6 6 Bxf6 Bxf6 7 e3 O-O 8 Qb3 dxc4 9 Bxc4 c5 10 dxc5 Nd7 11 Ne4 Nxc5 12 Nxf6+ Qxf6 13 Qc2 b6 14 O-O Bb7 15 Nd4 Rac8 16 Qe2 e5:

Tartakower annotated the full score in the first volume of his Best Games collection and commented that 17...b5 was ‘one more illustration of the paradox of a chess author that “the principal finesses in chess conflicts are furnished by pawn moves”.’ He concluded, ‘This is one of my best games’.

From page 56 of the February 1927 BCM:

‘The tit-bit of the round was expected to be the Réti-Tartakower game; but the former, who was evidently tired out by his six hours’ match-chess plus four hours’ blindfold display the previous day, did not do himself justice. Tartakower secured an endgame advantage on the queen-side, and playing with relentless accuracy he won the game in 45 moves.’

9860. Wallace v Forsyth

Noting a game headed ‘Mr Wallace (Sydney) – Mr Forsyth (Dunedin)’ on page 10 of the Dunedin Evening Star, 10 March 1906, Alan Smith (Stockport, England) seeks information about the occasion and asks whether the players were Albert Edward Noble Wallace and David Forsyth.

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 f5 3 d4 fxe4 4 Nxe5 Nf6 5 Be2 d6 6 Ng4 Be7 7 Bf4 O-O 8 Bg3 Nc6 9 Nc3 d5 10 Nb5 Ne8 11 c4 a6 12 cxd5 Bb4+ 13 Nc3 Qxd5 14 Ne3 Qxd4 15 Qb3+ Kh8 16 Rd1 Bxc3+ 17 bxc3 Qf6 18 Nd5 Qf7 19 Qb1 Nd6 20 Nxc7 Nf5 21 O-O Ra7 22 Qxe4 Qxa2 23 Bd3 Qf7 24 Bd6 Nce7 25 g4

25...Qg6 26 Bc5 b6 27 Bxe7 Nxe7 28 Qxg6 Nxg6 29 Bxg6 Rxc7 30 Bf5 Bxf5 31 gxf5 Rxc3 32 Rd6 Rb3 33 Rfd1 Kg8 34 Rd7 Rxf5 35 Rd8+ Rf8 ‘and Black wins’.

9861. BxRP (C.N.s 9805, 9809 & 9812)

Gerd Entrup (Herne, Germany) notes the conclusion of Botvinnik v Taimanov, USSR Championship, Moscow, 1952:

45 Bxh7 g6 46 Bg8 Rd5 47 h5 Rg5+ 48 Kf4 Rxh5 49 Ke4 Rf5 50 f4 Kd6 51 White resigns.

9862. Dermot Morrah

Leonard Barden (London) suggests that the writer of the article discussed in C.N. 9858 may have been Dermot Morrah (1896-1974).

We note that Morrah’s obituary on page 16 of The Times, 1 October 1974 referred not only to his long career with the newspaper as a journalist and leader writer but also to his interest in chess at university.

In the 1920 varsity match mentioned in C.N. 9807 Morrah, a student at New College, Oxford, played on fourth board, losing to C.M. Precious of St John’s, Cambridge. He contributed information about chess in Oxford on page 39 of the February 1920 BCM.

9863.

A Primer of Chess

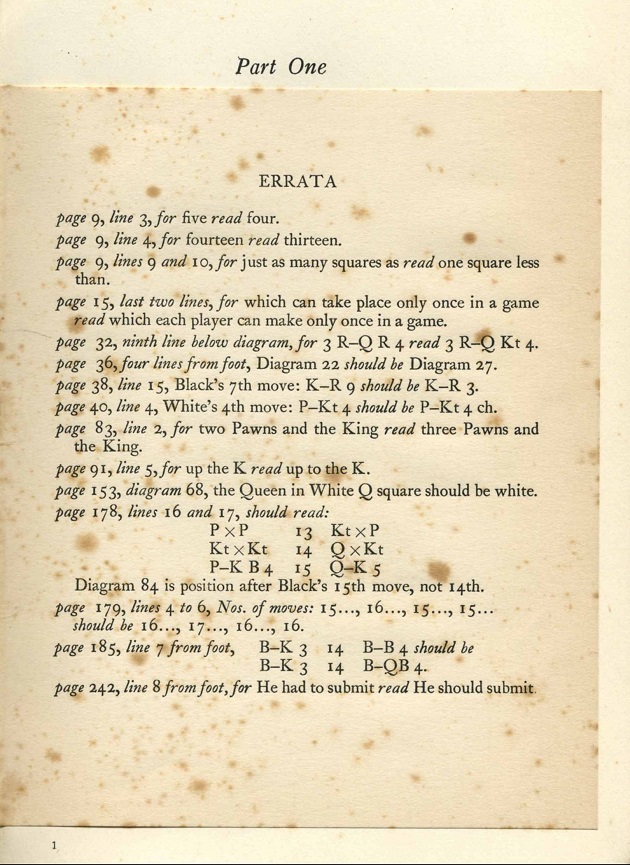

Future C.N. items will dip into some of Dermot Morrah’s chess writings (mainly book reviews), and we begin with a correction to Capablanca’s A Primer of Chess which he offered on page 206 of the Times Literary Supplement, 28 March 1935:

‘... it is not true that a bishop in the centre of the board commands just as many squares as a rook.’

The relevant passages were on pages 8 and 9 of the London, 1935 edition of A Primer of Chess:

‘It is interesting to note that because of the nature of the Rook’s move, it commands the same number of squares no matter where it is put.

‘It should be noticed that because of the nature of its movements a single B can move only over 32 of the 64 squares of the board. When in the centre of the board, however, it commands just as many squares as the Rook, which can move all over the board.’

The same wording appeared in the first US edition (New York, 1935), but we also have an edition which the American publisher, Harcourt, Brace and Company, brought out in the 1940s, with ‘A wartime book’ on the imprint page. Concerning the bishop, on page 9 ‘it commands just as many squares as the Rook’ was changed to ‘it commands just one square less than the Rook’. That amended wording is also in the various paperback editions of A Primer of Chess published in the United States in the latter part of the twentieth century. Page 5 of the algebraic version produced by Cadogan Chess, London in 1995 had ‘it commands one square less than the rook’.

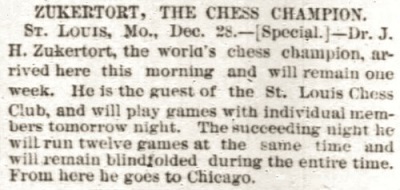

9864. An interview with Zukertort

Zukertort was sometimes called the chess champion of the world, as in this brief news report on page 6 of the Chicago Tribune, 29 December 1883:

That same day, the title of world champion was also used in an extensive interview with Zukertort. From page 8 of the St Louis Daily Globe-Democrat, 29 December 1883:

‘Dr J.H. Zukertort, the champion chessplayer of the world, and proprietor and editor of the Chess Monthly, published at Liverpool [sic], Eng., arrived in the city yesterday from Louisville on his trip around the world ...

In conversation with the champion a Globe-Democrat reporter elicited the following interesting facts concerning his life as a chessplayer, his opinion of American chessplayers and his faculty of playing blindfolded. Said he in reference to American players and in answer to the reporter’s question as to how chessplayers compared with those in England:

“There are not in America”, said he, “as many champions as in England, and the reason for this is easy to be understood. In England employers of large numbers of clerks have in several instances established chess clubs for their benefit, thus affording their employees a better kind of amusement under better surroundings than they would be likely to find otherwise. The expenses of such a club are moderate and are paid by the employer. Thus with these advantages, with such a widespread interest in the game, it naturally follows that England is far superior to this country in the modern development of the game. I, however, look forward to the day when the game will have become more popular in every large city than it is, for it is a recreation which requires no other stimulant than it has inherently – it exercises the brain without injury. Candidly speaking, I believe it is the best amusement the brain can find.”

“How is it, Doctor”, said the reporter, “that you became so proficient in blindfold playing, and what is your best record at such style of game?”

“My proficiency in this direction I ascribe to the reading of chess books. In reading them so much I discovered my ability to carry on a game as I read it, without even looking at a board. This ability or faculty I cultivated, and finding that I could play one game, I tried two, which was done successfully, keeping it up until in January 1868 I gave a public exhibition, my first one, in which I played seven games and afterwards nine at one time. I kept on gradually improving, until now I have the record of having played 16 blindfold games, the greatest number of simultaneous blindfold games ever played by any chessplayer. These games were played in the West End Chess Club, of London, 11 [sic – 16] December 1876, against 16 of the strongest amateur players of the St George’s and West End Clubs. I lost one, drew three and won 12.”

In answer as to when he first became a player of any prominence, the champion replied that it was in 1867, when he was editor of the Berlin Schachzeitung, a journal devoted to chess interests. “Do you recall any of your more brilliant and successful engagements, Doctor, and, if so, could you recount a few of them” was asked.

“Yes, the recollection requires but little effort. I am, I think, the only man living who has won two international tournaments, the one in Paris in 1878, in which I defeated Anderssen, the late German champion, Capt. Mackenzie, the American champion, Winawer, the Russian champion, and others. The other took place in London last spring, and was the largest chess tournament ever held, embracing in the list of famous players such names as Mackenzie, Steinitz, Blackburne, Chigorin, Rosenthal, Mason, Englisch, Winawer and Sellman. I defeated Anderssen in 1871, and was defeated by Steinitz in 1872. In 1875 I won from De Vere and Potter, from Rosenthal in 1880 and from Blackburne in 1881. These represent my greatest games.”

Is it true that you have received a challenge from Steinitz?

“Yes, and I have accepted it with the proviso that the contest shall take place in London upon my return to that city and that it shall be for the international championship and a purse of from £5 to £500 [sic] a side.”

The Doctor is, as his name implies, a Russian, having been born in Riga [sic], Russian Courland. He is a man of slight physique and massive head. In height he is but 5 feet 2½ inches, his weight is about 112 pounds and his head fills an eight and a half hat. His face is small, with a prominent nose, and he wears a mustache and short, sandy beard. A pair of large, restless and expressive eyes reflect an acute perception, together with a very active and nervous temperament. He articulates English very distinctly, with a slight continental accent, and is very fluent, his sentences being uttered with an ease and elegance that is remarkable for a Russian. When this fact was noticed by the reporter, he said:

“I speak or understand every language that is spoken in Europe, excepting the Turkish. Besides English, which was the last that I learned, I speak French, German, Polish, Russian, Italian and Spanish. I understand Danish and Portuguese and, of course, speaking Russian and Polish, understand all the Slavonic dialects, such as Czech or Bohemian, Serb or Servian, and Bulgarian. There is no part of Europe in which I cannot travel and understand the native, and also make myself understood.”

“Have you enjoyed your visit to this country?”

“I have enjoyed myself splendidly. I started with a delightful trip across the ocean and, indeed, have enjoyed the country and mingling with the people since I landed. I came to see the country, and not as a chess champion, but of course do not decline the honor of invitations to visit local chess clubs wherever I go. I delight in the game, and also delight to meet the devotees in this country. In New York I was royally entertained by the Manhattan Chess Club. Two hours after I arrived at my hotel I was at their rooms. They complimented me with an honorary membership. At their rooms and at the Manhattan and Union League Clubs I played a great many offhand games, in which I had as competitors all the leading chessplayers excepting Capt. Mackenzie. He did not ask me to play with him, and I, as international champion, could not very well ask him to play with me. I also gave exhibitions of blindfold and simultaneous playing. In the simultaneous playing I played 24 games against as many players, each at board. Passing from one board to another, I would look at each and make my move as I went along. Those who were opposed to me had from the time I left their boards until I returned in which to make a move. In that way the games were played, and I won 19, drew two and lost three. The blindfold games I played sitting in a corner with my back to the boards. A secretary was provided for me, and he called and recorded every move for each game. While the games were in progress I had a mental view of each board that enabled me to take up its game as it came to me in turn almost the same as if I were looking at it. The moment No. 2 was called, No. 1 would disappear from my mind and No. 2 would appear before me mentally. I saw, as it were, the negative of a photo. I saw a shadowy board with no color, but the men and their positions were as distinctly before as if I had a clear view of the board. While I am playing blindfold games you can talk to me on any subject but chess and it does not disturb me. There are, as absolute facts, only two first-class blindfold players – Mr Blackburne, the British champion, and myself. The faculty is not a common thing among noted chessplayers. There are others possessing it, but they are inferior.”

“Is your ability to play blindfold games the result of a naturally retentive memory or mental training?”

“It is both. Originally a natural faculty, subsequently developed by training. My memory received a very unusual training, beginning when I was only five years old. My godfather, an old bachelor, was a professor of mathematics, and he began training me in mathematics before I could read or write. As a result, when I was seven years old I knew algebraic equations of the first degree and could demonstrate that the square of a hypothenuse was equal to the sums of the squares of the two other sides.

While in Washington, which I visited expressly to see the capital of the United States, I made a call at the rooms of the local chess club, which, I am sorry to say, I found in a dying condition. They had card games and chess mixed in together, and the two, in my opinion, do not blend harmoniously. It is not that I object to cards that I say this, for in London I play ten times as much whist as I do chess, but I play whist at the whist club and chess at the chess club.”

“Have you any favourite opening?”

“No, no. Book openings are to a great extent ignored by good players. The stronger the players, the more the book openings are discarded. In the London tournament I played nearly all my games regardless of book openings.”

“While in St Louis I will be at the Mercantile Library every afternoon, ready to play offhand games with any of your local players. Offhand games, I want you to understand, are vastly different from set match games in which a player settles down to play carefully and take no chances. In playing them one will venture moves regardless of results, and often gives an opponent a winning position. No such ventures are made in set games.”’

9865. A knight on e6 (C.N.s 3514 & 9375)

An observation by Zukertort after 26 Ne6 in the simultaneous game Steinitz v Maas, London, 5 November 1873:

‘The appearance of the knight at K6 is generally, for the opponent, the proper signal to strike his colours.’

26 Ne6 Qe8 27 Bxc1 Rf7 28 g4 Qa4 29 g5 c2 30 gxf6 cxb1(Q) 31 Nh6+ Kh8 32 Nxf7+ ‘and mates next move’.

Source: City of London Chess Magazine, May 1874, pages 97-98.

When the game Steinitz v von Bardeleben, Hastings, 1895 was shown in a ‘Chess Movies’ article on page 336 of the November 1949 Chess Review, the following comment referred to 19 Ne6:

‘A knight at K6 is like a bone in the throat, says Steinitz.’

For the same attribution, see I.A. Horowitz’s books How to Win in the Chess Openings (New York, 1951), page 44, and How to Win at Chess (New York, 1968), page 50, but where did Steinitz make the comment?

From page 212 of the first volume of Kasparov’s Predecessors series, before 16 Ne6 in Lasker v Capablanca, St Petersburg, 1914:

‘... the knight at e6 will be like a bone in his throat!’

Exclamation marks do not enliven clichés.

9866. The Berlin Defence

An obsolete comment on the Berlin Defence was provided by W.N. Potter in his notes to a Lord v Bird game on pages 144-146 of the City of London Chess Magazine, July 1874. After 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 he wrote:

‘Very rarely do we now meet with this defence. Its appearance is as the trotting out of an old Derby favourite years after being backed for the blue ribbon. We confess to a sense of refreshment at any break in the monotonous reiteration of P to QR3.’

9867. Resignation (C.N. 9857)

Another item relevant to this topic is C.N. 9400 (Tartakower on Najdorf v Cortlever, Buenos Aires, 1939).

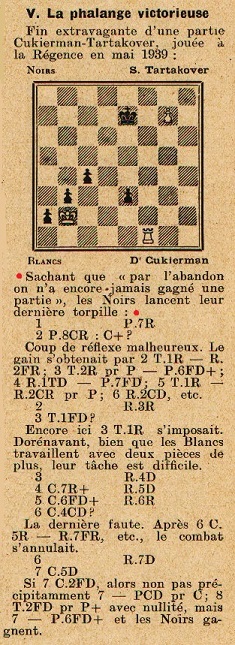

An addition from Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) is the conclusion of Cukierman v Tartakower, Paris, 1939, annotated by the latter on pages 102-103 of La Stratégie, July 1939:

9868. A Primer of Chess (C.N. 9863)

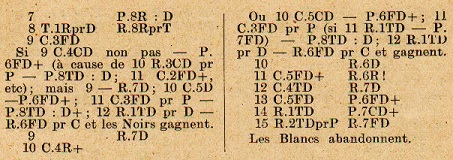

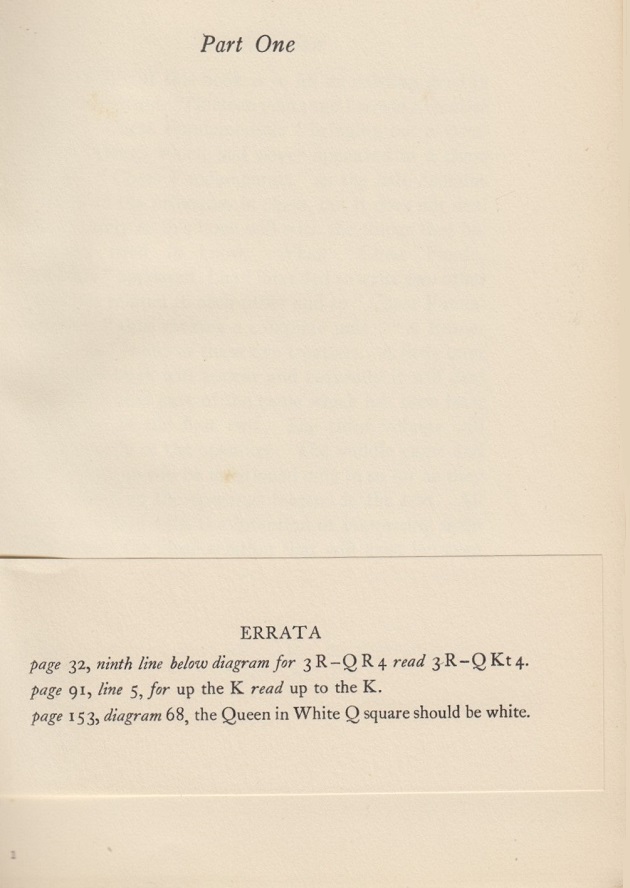

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) reports that his copy of Capablanca’s A Primer of Chess (London, 1935) has this errata sheet attached to page 1:

Our copy of the book has a much shorter list:

9869. A giveaway

Even in the pre-Internet age, some people required only a few words or lines to give themselves away in terms of unfairness and/or inaccuracy. From page 10 of The Collier Quick and Easy Guide to Chess by Richard Roberts (New York, 1962):

That is the full ‘potted biography’ of Staunton. On the same page the entry on Capablanca began:

A careful writer would have avoided ‘and uncle’, ‘23’, ‘cajoled’ and the airy assertion about women.

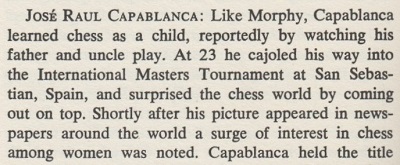

9870. A whetstone

From page 67 of the American Chess Review, November 1886:

There would be little point seeking the ‘original’ quotation in the Quebec Chronicle because the remark, by H.A. Kennedy, had been published decades earlier, on page 305 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1848:

In an article entitled ‘Hazlitt and Chess’ on pages 372-373 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1855 Kennedy referred back to his observation:

‘I believe the proper way to employ chess, to quote from an article that appeared in this journal some years back, is to make it “a whetstone on which to grind and sharpen the higher faculties of the mind”.’

Both texts were in Kennedy’s book Waifs and Strays (London, 1862), on pages 89 and 118 respectively.

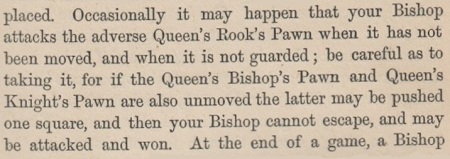

9871. BxRP (C.N.s 9805, 9809, 9812 & 9861)

Two additions concerning the queen’s rook’s pawn are given below, the first being from page 55 of The Book of Chess by George H. Selkirk (London, 1868):

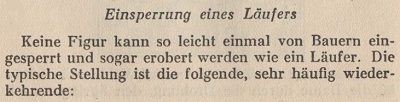

Tarrasch gave an example on pages 202-203 of Das Schachspiel (Berlin, 1931):

The position was on pages 144-145 of the English edition, The Game of Chess (London, 1935).

9872. Nameless

The series of portraits by Frederick Orrett (C.N.s 9722, 9725, 9751 and 9811) received from Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) continues with two nameless ones:

Mr McDowell suggests that the masters depicted are Důras and Schlechter.

9873.

Alekhine and Capablanca fake photograph

C.N. 8073 noted that the fake photograph of Alekhine and Capablanca was on page 250 of Alekhine’s My Best Games of Chess 1908-1937 (Russell Enterprises, Inc., Milford, 2013). It had already appeared on page 167 of the same publisher’s José Raúl Capablanca by I. and V. Linder (Milford, 2010), and it has now turned up again on page 159 of the same publisher’s Alexander Alekhine by I. and V. Linder (Milford, 2016):

Our feature article on the picture mentions that it was used too on page 164 of the Linders’ Das Schachgenie Aljechin (Berlin, 1992). It is also in the Russian editions of their Alekhine monograph (Moscow, 1992, page 159, and Moscow, 2006, page 171). Furthermore, it was in their Russian books on Capablanca (Moscow, 2005, page 128, and Moscow, 2011, page 155).

9874. A knight on e6 (C.N.s 3514, 9375 & 9865)

From Elements of Positional Evaluation by Dan Heisman (Coraopolis, 1990), pages 21-22:

‘There are many famous quotes on these subjects, like Adolph [sic] Anderssen’s “Once get a knight firmly posted on King 6 and you may go to sleep. Your game will then play itself.”’

From Elements of Positional Evaluation by Dan Heisman (Milford, 2010), page 28:

‘There are many famous quotes on these issues, an example being Steinitz’s “Let me establish an unassailable knight on K6 [e3/e6] and I can go to sleep for the rest of the game.”’

In each case Heisman provided a sort of source: respectively, ‘Chernev, The Bright Side of Chess, p. 111’ and ‘Chess, Jan. 8, 1955, p. 17’. Both those references were mentioned in C.N. 3514, but they lead nowhere. The latter was merely a sourceless answer to a Christmas quiz.

An addition from page 27 of How Not to Play Chess by E. Znosko-Borovsky (London, 1931):

‘The great Steinitz used to say that if he could establish a Kt at his K6 or Q6, he could then safely go to sleep, for the game would win itself.’

9875. Phillips v Ascher

Page 78 of the 15 February 1885 issue of the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle had a game ‘played last month in Toronto between Mr Phillips, of that city, and Mr Ascher, of Montreal’:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 Bc5 3 Nf3 d6 4 Bc4 Nf6 5 d3 O-O 6 Nc3 Ng4 7 Rf1 Nxh2 8 Rh1 Ng4 9 Qe2 Bf2+ 10 Kf1 Bb6 11 Ng5 h6 12 f5 Nf6 13 Qf3 Nc6 14 Qh3 Na5

15 Nxf7 Rxf7 16 Bxh6 Nxc4 17 Bxg7 Rxg7 18 Qh8+ Kf7 19 Qxd8 Ne3+ 20 Ke2 Rxg2+ 21 Kf3

21...Bxf5 22 Qxf6+ Kxf6 23 Nd5+ Nxd5 24 Kxg2 Ne3+ 25 Kf3 Bg4+ 26 Kg3 Rg8 27 c3 Be2+ 28 Kf2 Rg2+ 29 Ke1 ‘and Black mates in four moves’.

9876. Ten thousand

From page 45 of The Adventure of Chess by Edward

Lasker (New York, 1950), in a paragraph concerning the

Soviet Union:

‘Ten thousand women recently took part in preliminaries organized for the purpose of qualifying competitors for the national women’s title.’

Although Lasker used the word ‘recently’, the following is on page 239 of the Australasian Chess Review, 10 September 1936:

‘Over ten thousand women are competing in the eliminating sections of the women’s chess championship of the USSR. Our readers will have got so used to these staggering chess figures from Russia that comment is not required.’

Even so, corroboration is always welcome.

9877. Grace in defeat

‘There cannot be many men who are capable of losing a game to a woman without turning purple with rage. We venture to predict that as soon as men learn to accept defeat more gracefully, more women will play chess, and play it better. But when are men likely to start accepting defeat more gracefully?’

Source: page 290 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949).

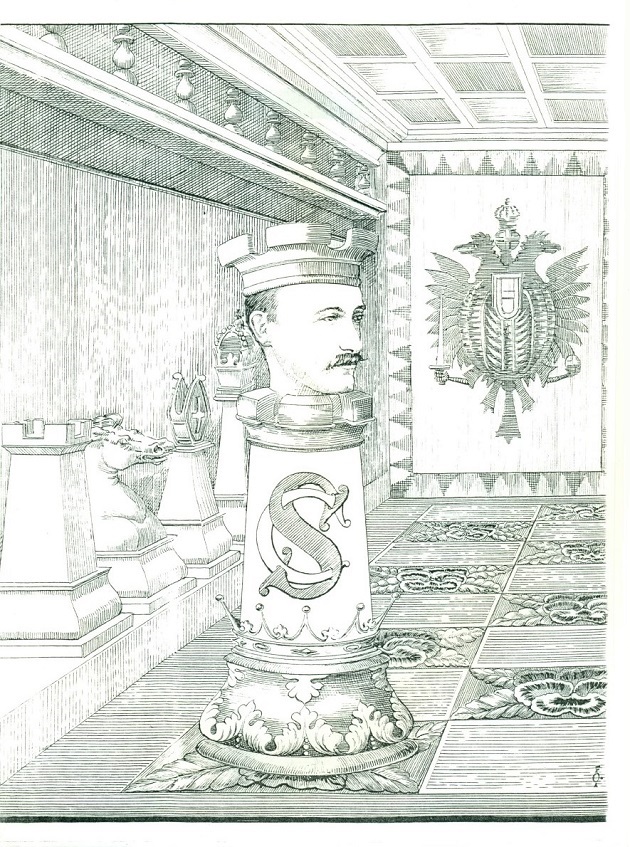

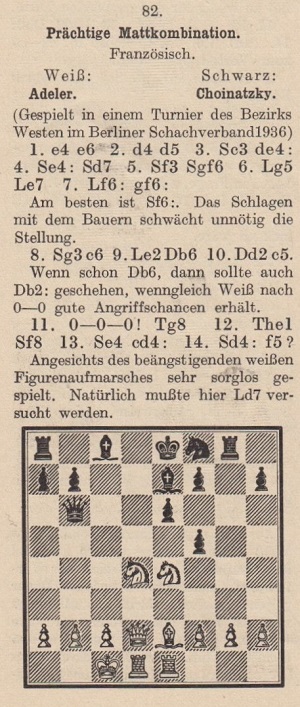

9878. Adeler

v Choinatzky

From page 41 of the March 1938 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

The game (1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Nd7 5 Nf3 Ngf6 6 Bg5 Be7 7 Bxf6 gxf6 8 Ng3 c6 9 Be2 Qb6 10 Qd2 c5 11 O-O-O Rg8 12 Rhe1 Nf8 13 Ne4 cxd4 14 Nxd4 f5 15 Nxf5 exf5 16 Nf6+ Qxf6 17 Qd8+ Bxd8 18 Bb5 mate) had been played not ‘last month’ but nearly two years previously. It was published on page 188 of the 15 June 1936 issue of Deutsche Schachblätter:

The game was in the ‘Chess Caviar’ column on page 6 of Chess Review, November 1948 and on pages 275-276 of Chernev’s 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955). In each case it was correctly headed ‘Berlin, 1936’.

9879. The fascination of chess history

‘There is no subject which presents so many interesting and fascinating matters of inquiry to the chess lover who has antiquarian proclivities as does the history of the game; no subject concerning which there has been so much unprofitable speculation, so many baseless theories, so many misleading and deceptive statements by those who claimed to have made the origin of the game the special object of their research and study, and who have assumed to speak authoritatively.’

Source: Brentano’s Chess Monthly, December 1881, page 380.

9880. Fischer’s reign

‘This must surely be simply the stupidest remark made about any aspect of chess in 1985.’

That observation by a correspondent, W.D. Rubinstein, was published in C.N. 1121 (March-April 1986). It concerned a review of The Oxford Companion to Chess by D. Hooper and K. Whyld (Oxford, 1984) on page 33 of the December 1985 Chess Life. The reviewer, Larry Parr, devoted well over half his space to complaining that the Companion was pro-Soviet, and in C.N. 1079 we quoted a small sample, such as this:

‘But the grand prix for breathtaking mendacity must be this entry on Garry Kasparov ...’

In C.N. 1143 Ed Tassinari (Scarsdale, NY, USA) commented:

‘I would like especially to commend and strongly support Professor Rubinstein (C.N. 1121) for saying what needed to be said concerning the increasingly ludicrous remarks of L. Parr (in general, and specifically in his review of The Oxford Companion to Chess). Clearly some statement must be made regarding the deterioration in the quality (and the almost blatant jingoism) of Chess Life since Parr assumed the editorial position. Another disturbing development within the Chess Life/United States Chess Federation hierarchy appears to be linked in a way to this xenophobia and red-baiting: the sudden concern to declare Bobby Fischer world champion, a kind of obsessive cry to “bring back Bobby” while vilifying Karpov and the entire Soviet chess establishment for the behind-the-scenes chess politics that drove Fischer from chess, presumably. Certainly the Soviets have had more than their share of unsavory wheeling and dealing since the advent of the existing world championship qualifying system. But this insidious use of the specter of Fischer seems motivated solely by the political leanings of certain individuals at the apex of US chess, to be wielded like a club for whatever purposes deemed necessary.’

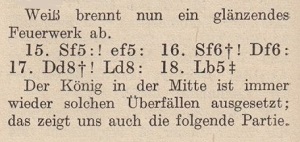

Also in C.N. 1143 we quoted from a Symposium on ‘The Karpov Era’ on pages 26-34 of the March 1986 Chess Life. For example, although Arnold Denker observed regarding Karpov, ‘even his severest critics never questioned his right to reign’, four pages later Charles Pashayan wrote:

‘... is it really any wonder that the World Chess Champion Bobby Fischer remains aloof from public chess?’

And here is Lev Alburt:

‘Isn’t it time that we Americans recognize the truth: Bobby Fischer is the reigning world champion.’

He called Kasparov ‘the new FIDE world champion’.

Chess Jottings mentions that the contribution by Larry Evans to the Symposium had this remark about Karpov:

‘He will go down in history as the man who avoided a match with Bobby Fischer and then eluded him for the next ten years.’

The issue of Chess Life (December 1985) which contained the Companion review also published, on page 9, a letter from Lev Alburt with the following:

‘Mr Larry Goldberg and myself were active co-sponsors and defenders of Leland Fuerstman’s motion for the USCF to declare Bobby Fischer the world champion.’

Alburt then mentioned ...

‘... an idea for promoting chess: why not start off each issue of Chess Life with a small picture of Bobby Fischer in the upper right hand corner of the cover?

Your magazine is an excellent journal, but only a few hundred thousand of the thirty million Americans who play chess even know about it or, for that matter, about the USCF. A far larger number know the picture of Bobby Fischer. What better way could there be to attract attention, to increase newsstand sales, and to bring into the USCF thousands of new members?’

Reuben Fine

(frontispiece of his 1987 book The Forgotten Man:

Understanding the Male Psyche)

Another letter in Chess Life in 1985 (on page 6 of the May issue) was from Reuben Fine. Whilst criticizing the historical circumstances, he at least acknowledged that Karpov had become world champion in 1975 and had retained the title since then. Fine opined that ‘for the USSR chess is only a footnote to politics’ and he proposed that ‘the US Chess Federation should undertake bold and constructive action’:

‘I recommend that the United States take the initiative of splitting up FIDE into two separate organizations: one for the free world and one for the communist world. The best player from each world would then meet on as neutral soil as possible to play for the world championship.

If it is feasible, Robert Fischer should be brought back and declared the champion of the free world. If the Soviet champion should then refuse to meet Fischer in a match going to the man who first wins ten games, the Western countries should declare Fischer the world champion and let the two federations go their respective ways.’

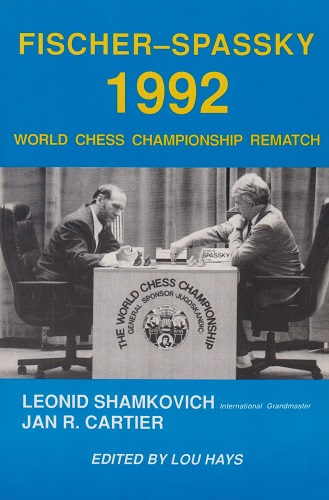

Despite such contributions to Chess Life, there has been almost universal acceptance that Kasparov became the chess champion of the world in November 1985 when he defeated Karpov in their second match. Seven years later, however, further attempts were made to shunt Kasparov aside, when Fischer played his second match against Spassky. In Instant Fischer, which examined six volumes on that 1992 match, we commented:

‘The books, all written before the Kasparov-Short world championship controversy arose, show a surprising willingness to entertain Fischer’s claims to the world championship.’

It is, though, necessary to bear in mind, and seek further information on, Kasparov’s ‘co-champion’ remark to Fischer, quoted in our above-mentioned feature article from page 282 of No Regrets by Yasser Seirawan and George Stefanovic (Seattle, 1992).

Anybody wishing to argue that Fischer was still the world champion in 1992 should, logically, also assert that he remained so until his death in 2008. That would make him the longest-reigning chess champion in history and would mean that Kramnik, for instance, never held the title at all. In reality, any chronicle which gives Fischer’s dates of tenure as other than ‘1972-75’ is, at best, eccentric.

Everything, of course, goes back to FIDE’s decision to remove the title from Fischer in 1975. Who has written the most detailed, accurate and equitable account?

9881. Liverpool, 1923

In one of the best-known novels by Agatha Christie, Ten Little Niggers (London, 1939) – later retitled And Then There Were None and Ten Little Indians – the marooned characters are slow to realize that the name ‘U.N. Owen’ signifies ‘Unknown’.

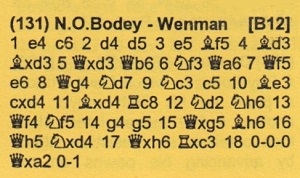

From page 54 of Hastings 1922/3 Margate 1923 Liverpool 1923 by A.J. Gillam (Nottingham, 1999), in the ‘Other Sections’ part concerning Liverpool:

As so often, Gillam mysteriously omitted to specify the source of the game, and he gave no sign of realizing that the name ‘N.O. Bodey’ was a whimsical pseudonym.

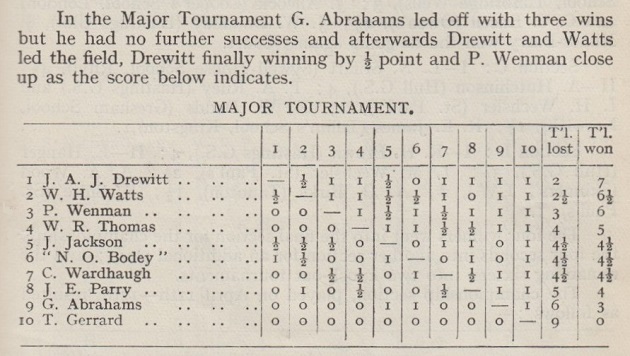

Ten players participated in the Liverpool tournament, and the pseudonym was in quotation marks on page 165 of the May 1923 BCM:

The quotation marks were retained by Jeremy Gaige on page 592 of volume four of Chess Tournament Crosstables (Philadelphia, 1974), which duly gave a reference to the above BCM table. Neither the quotation marks nor the source reference appeared on page 56 of Chess Results, 1921-1930 by Gino Di Felice (Jefferson, 2006).

Of the contemporary newspaper reports that we have seen, none revealed the identity of ‘N.O. Bodey’. The Scotsman of 2 April 1923, page 9, reported that the Major Tournament included ‘a Liverpool amateur who prefers to remain anonymous’. Page 6 of the Daily Telegraph, 6 April 1923 referred to ‘the gentleman who prefers to play under the euphonious pseudonym of N.O. Bodey’.

Page 55 of the Gillam booklet also had a sourceless snippet (moves 22-25) from the game between G. Abrahams and J. Jackson, but the full score of that first-round game can be shown here, from page 8 of the Scotsman, 3 April 1923 and page 9 of the same day’s edition of the Western Daily Press:

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 c3 d5 4 Be2 dxe4 5 Qa4+ Bd7 6 Qxe4 Nc6 7 d4 h6 8 Be3 Qb6 9 Qc2 Rc8 10 Na3 cxd4 11 Nc4 Qc7 12 Nxd4 Na5 13 Nxa5 Qxa5 14 O-O Nf6 15 Rfe1 Bd6 16 h3 b5 17 Qd3 b4 18 c4 Ke7

19 c5 Bb8 20 Bf3 Qc7 21 g3 Rhd8

22 c6 Bxc6 23 Nxc6+ Qxc6 24 Qxd8+ Kxd8 25 Bxc6 Rxc6 26 Rac1 Kd7 27 Red1+ Nd5 28 Rc5 a6 29 Kf1 Bd6 30 Rxc6 Nxe3+ 31 fxe3 Kxc6 32 Kf2 a5 33 b3 Kc7 34 e4 Be5 35 g4 Kc8 36 Ke2 Kc7 37 Kd3 Kb7 38 Kc4 Kc8 39 Kb5 Bc7 40 Kc6 f5 41 gxf5 exf5 42 exf5 Bd8 43 Re1 Kb8 44 Re8 Kc8 45 Rh8 Resigns.

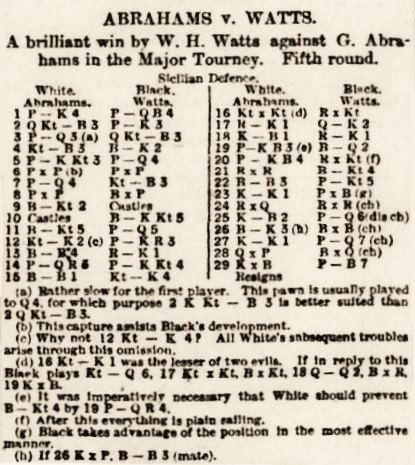

Later in the tournament, the 15-year-old Gerald Abrahams was defeated by W.H. Watts in a game which, though absent from the Gillam booklet, was published on page 234 of the Chess Amateur, May 1923, with notes from the Daily Telegraph. Below is what appeared in the newspaper on page 6 of its 6 April 1923 edition:

1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 e6 3 d3 Nc6 4 g3 Be7 5 Nf3 d5 6 exd5 exd5 7 d4 Nf6 8 dxc5 Bxc5 9 Bg2 O-O 10 O-O Bg4 11 Bg5 d4 12 Ne2 h6 13 Bf4 Re8 14 a3 g5 15 Bc1 Ne5 16 Nxe5 Rxe5 17 Re1 Qe7 18 Kf1 Re8 19 f3 Bd7 20 f4

20...Rxe2 21 Rxe2 Bb5 22 Bf3 g4 23 Ke1

23...gxf3 24 Rxe7 Rxe7+ 25 Kf2 d3+ 26 Be3 Bxe3+ 27 Ke1 d2+ 28 Qxd2 Bxd2+ 29 Kxd2 f2 30 White resigns.

The game had also been published on page 4 of the Yorkshire Post, 5 April 1923, which wrote of Abrahams: ‘He defends a losing game with extraordinary resource.’

As regards the Premier Tournament in Liverpool, won by Mieses ahead of Maróczy, Sir George Thomas and Yates, we add a further score which is absent from the Gillam booklet, the second-round game between A. Louis and F.D. Yates played on the morning of 2 April 1923:

1 c4 Nf6 2 d4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 e4 d6 5 f4 O-O 6 Nf3 Nc6 7 d5 Nb8 8 Bd3 e5 9 fxe5 dxe5 10 Bg5 h6 11 Be3 Qe7 12 O-O Ng4 13 Qe2 Nxe3 14 Qxe3 Nd7 15 Rae1 a6 16 b3 Nf6 17 Kh1 Bd7 18 Nh4 Ng4 19 Qg3 Bf6 20 Nf3 h5 21 h3

21...h4 22 d6 cxd6 23 Nd5 hxg3 24 Nxe7+

24... Kg7 25 Nxg6 Nf2+ 26 Kg1 fxg6 27 Re3 Rac8 28 Be2 Bd8 29 Nxe5 dxe5 30 Rxg3 Bb6 31 Kh2 Nxe4 32 Rd1 Bc6 33 White resigns.

Source: Western Daily Press, 4 April 1923, page 3.

| First column | << previous | Archives [141] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.