Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [142] | next >> | Current column |

9882. New York, 1987

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) has forwarded two photographs which he took during the New York Open tournament in 1987:

Michael Rhode, Boris Spassky, Joel Benjamin

John Fedorowicz, Lajos Portisch

9883. Adeler v Choinatzky (C.N. 9878)

Thomas Binder (Berlin) informs us that the family of Erhard Adeler has provided his years of birth and death: 1901 and 1976.

9884. Christopher Nicole

From page 61 of Introduction to Chess by Christopher Nicole (London, 1973):

‘It is difficult to imagine a position very much stronger than both sides before the first move; so from then on you are steadily weakening yourself. What you have to try to do is weaken the other chap more.’

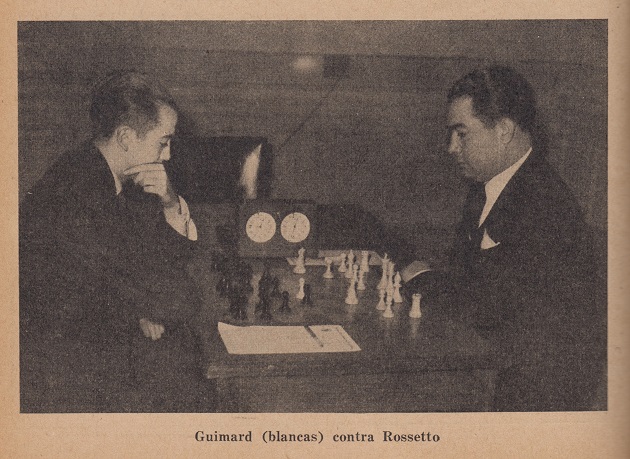

9885. Photographic archives (18)

From our archive collection, photographs of the late Victor Gavrikov have been presented in C.N. 9590 and in Chess Jottings. A further picture (Biel, 1991) is added now:

9886. Bled, 1959

More and more archive film on chess is coming to light, including particularly interesting footage from the Candidates’ tournament, Bled in 1959.

Two screen-shots:

Bobby Fischer

Mikhail Tal

9887. Honourable uncertainty

Chess and the English Language and Chess Punctuation have drawn attention to a common oddity: the way question marks are increasingly tagged on to sentences which are not questions.

In other circumstances, however, many writers make insufficient use of question marks. When the facts about, for example, a player’s identity, a date or a venue are open to doubt, the reader needs to be informed accordingly, and a question mark helpfully signals caution. Nonetheless, some writers prefer to plump, perhaps at random, for one of the options, thereby presenting as a certainty a matter on which the evidence is mixed. A question mark added in, for instance, a game heading, to indicate that the factual details are not clear-cut, is a sign of strength, not weakness.

There are many game-scores (e.g. Lasker v Thomas, London, 1912 and Réti v Alekhine, Baden-Baden, 1925) where the exact moves played are open to doubt, as well as games, such as Adams v Torre, New Orleans, 1920, which may not even have occurred over the board. It may seem obvious that a chess writer should differentiate between what is known for sure and what is obscure, but readers are often denied that basic service.

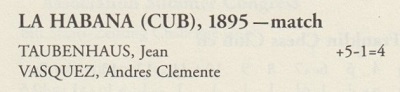

Pace the plumpers, the final score of a match may also be dubious, and as an example we take a contest in Havana between Jean Taubenhaus and Andrés Clemente Vázquez. Anyone consulting Hundert Jahre Schachzweikämpfe by P. Feenstra Kuiper (Amsterdam, 1967) will be told, on pages 97 and 98, that in 1895 Taubenhaus won +5 –1 =4. The spelling ‘Vasquez, Dr Andreas C.’ on page 98 does not inspire confidence, and the reader seeking corroboration of the score may well turn to page 161 of Chess Results, 1747-1900 by G. Di Felice (Jefferson, 2004):

With not a question mark in sight, can it therefore be assumed that the information is correct? Not at all. Firstly, the match was played in 1894-95. That ‘detail’ apart, we give below four earlier reports on the result of the match, all different from each other:

- Taubenhaus 4 Vázquez 1 =5. La Stratégie, 15 February 1895, page 54;

- Taubenhaus 4 Vázquez 1 =2. BCM, March 1895, page 114. However, page 66 of the February 1895 issue had stated that ‘the winner should make the best score in ten games played; and by the last accounts the score stood Taubenhaus 3 Vázquez 1, drawn 3’;

- Taubenhaus 5 Vázquez 1 =4. Deutsche Schachzeitung, April 1895, page 124;

- Taubenhaus 4 Vázquez 1 =1. Ajedrez en Cuba by C. Palacio, page 205.

The next step is to try to assemble the full set of game-scores, however many there were, and in that exercise databases are of no help.

Through old-fashioned methods we have so far traced the following:

- First game: Vázquez v Taubenhaus, 29 December 1894. Bird’s Opening. 1-0 (62). La Stratégie, 15 February 1895, pages 46-47 (notes by Vázquez). The Times, 29 January 1895, page 14 (42 BxKt and wins);

- Second game: Taubenhaus v Vázquez, 30 December 1894. Sicilian Defence. 1-0 (46 + a note that some additional moves were played). La Stratégie, 15 February 1895, pages 47-48 (notes by Vázquez). In the Albany Evening Journal, 19 January 1895 (page ?) Pollock gave the same game, also as far as move 46, with ‘notes condensed from those of Sr. Vázquez in the Diario de la Marina’;

- Fourth game: Taubenhaus v Vázquez, (? 1895). Sicilian Defence. 1-0 (40). Deutsche Schachzeitung, May 1895, page 141;

- Fifth game: Vázquez v Taubenhaus, 5 January 1895. Bird’s Opening. Drawn (77). La Stratégie, 15 March 1895, pages 76-77 (notes by Vázquez);

- Sixth game: Taubenhaus v Vázquez, 7 January 1895. Philidor’s Defence. 1-0 (28). Baltimore Sunday News, 23 January 1895, page ? (notes by Pollock). San Francisco Chronicle, 27 April 1895, page 10 (notes by Martínez).

A future C.N. item will give all the available game-scores, together with any additional information that can be found with readers’ help.

9888. Alexander on Alekhine

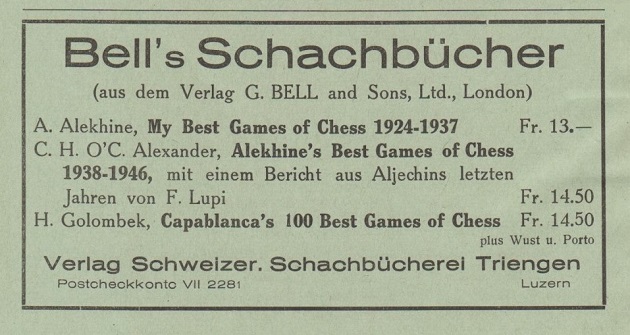

An advertisement from the back cover of the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, December 1947:

C.H.O’D. Alexander’s book was published nearly two years later, the dates in the title being 1938-1945. No material by Francisco Lupi was included, and we wonder whether the intention had been to give a new text by him or merely to reproduce the articles which, as discussed in C.N. 4388, he published shortly after Alekhine died.

The years in the book title are given as 1938-46 in the skimpy ‘Bibliography’ on page 6 of Alekhine move by move by Steve Giddins (London, 2016), and the following page has Mr Giddins’ contribution on the topic of Alekhine’s Death:

‘And even his death has been questioned, with suggestions he may have been murdered by a Soviet hitman. Admittedly, this latter theory has much less substance, and should probably be grouped with those that suggest the moon landings were faked and that Princess Diana was murdered by Lord Lucan, with Elvis Presley (or was it Dick Cheney?) driving the getaway car.’

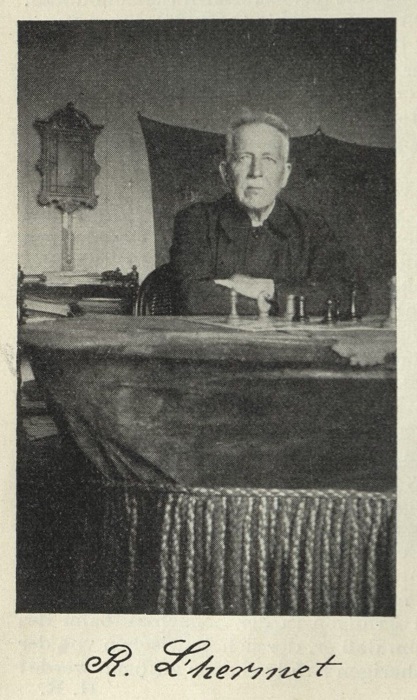

9889. Rudolf L’hermet (C.N.s 9697 & 9708)

From page 2 of the Deutsche Schachzeitung, January 1941:

We were unable to make a good scan of this picture and are therefore grateful to the Cleveland Public Library for providing the above. The Library has also kindly sent us the two photographs in our next item.

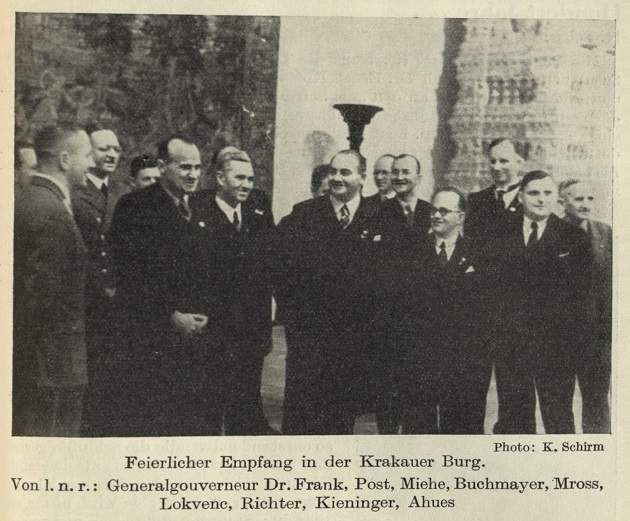

9890. Hans Frank

Additions to Hans Frank and Chess:

Deutsche Schachzeitung, November 1940, page 169

Deutsche Schachzeitung, November 1941, page 162.

9891. Chess for pleasure only

From page 177 of the July 1875 City of London Chess Magazine (edited by W.N. Potter):

‘We have often heard the expression, “I play for pleasure only”. We know well what to expect when the utterer is seated over the chess board. His nose is the limit of his vision. Helpless and aimless, like a fly with its head cut off, he gropes about here and there the easily-mastered victim of his opponent if the latter have any skill, and otherwise the ignoble slave of chance. Why chess should be the refuge of so many men whose brains seem to have been drowned long ago in the serum of sloth it is difficult to understand. At cricket no fielder walks languidly after the ball while the runs are being made; no batsman saunters to the opposite wicket while the longstop is hurling back the captured missile. If Smith and Brown row together it does not do for one to tell the other, as an excuse for lazy paddling, “I only row for pleasure”. Anathema, we say, to all kinds of indolence. There is no excuse for it in pleasure more than in anything else. He who would enjoy chess must let his mind take up its residence in his eyes, and to such a one we shall be glad to be of service, but as to those whose stupidity is the offspring of their own laziness, let them, if they will, stay in caissadom, but withal assume that modesty which is not their invariable characteristic, so that henceforth seeking rather to hear than to be heard, they may in time acquire that knowledge the first sign of which is the consciousness of its absence.’

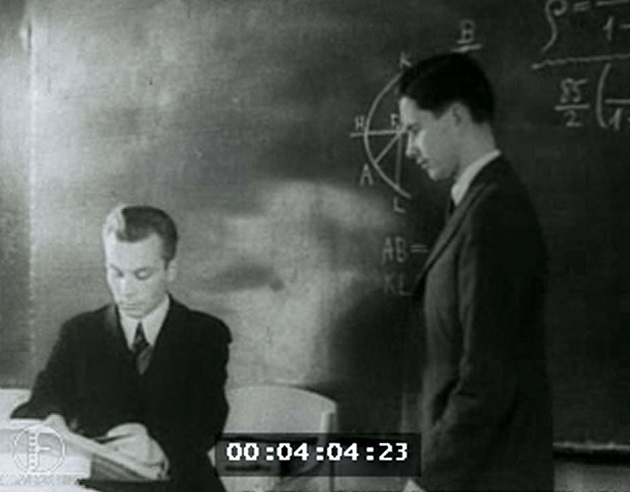

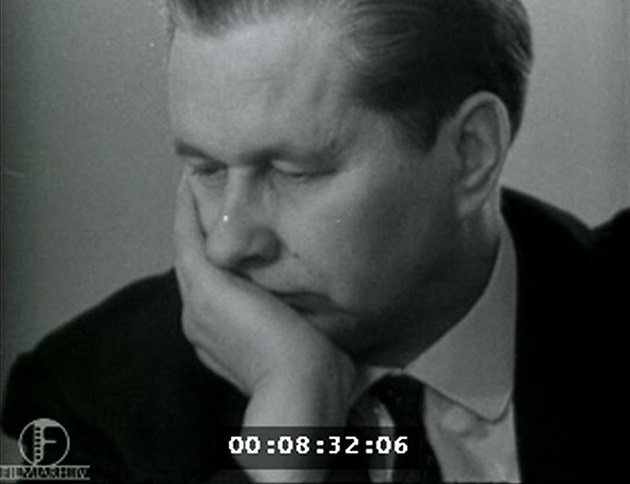

9892. Keres on film

Concerning Chess Masters on Film, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) writes:

‘In addition to audio files with Keres interviews and speeches, the Estonian Film Archives contain a significant number of film files featuring him, and some of the material has been digitized and made available online. Among the highlights: a 1938 clip of Keres in a tournament (and playing blitz). A 1941 feature on his mathematics examination at the University of Tartu:

1945 film showing Keres in tournament play (with other Soviet masters):

There is a seven-minute montage on the 1947 USSR Championship, and a brief 1956 clip showing Keres in a simultaneous exhibition at a house of pioneers in Tallinn. Also, coverage of his golden jubilee celebration (1966) and remarkable 1975 footage of his funeral:’

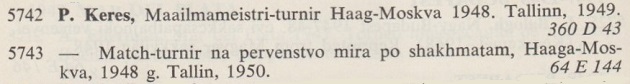

9893. Keres book

On any list of favourite chess players, personalities and writers, Paul Keres is likely to be ranked highly. At about 3:50:00 in a broadcast during round 11 of the US championship in St Louis on 25 April 2016, Yasser Seirawan asked Garry Kasparov about his favourite chess books. The answer included a reference to ‘Keres, 1948’. The book in question, on the 1948 world championship match-tournament, has also been praised recently by Boris Gelfand, in a ChessBase interview conducted by Sagar Shah.

From page 262 of the catalogue Bibliotheca Van der Linde-Niemeijeriana (The Hague, 1955):

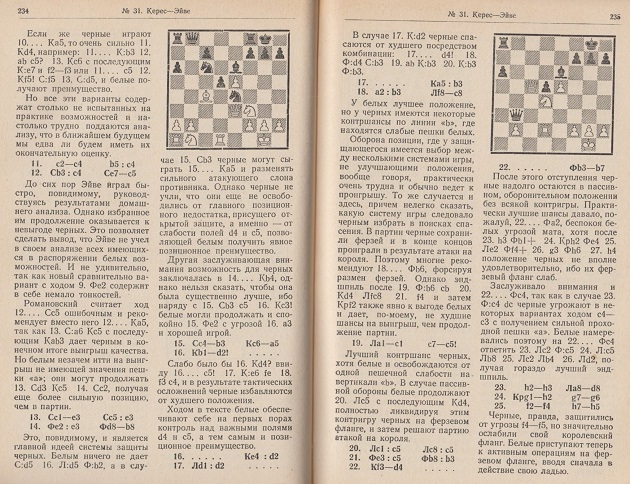

As an indication of the quality of Keres’ work, two pages (on his 16th-round win against Euwe in Moscow on 22 April 1948) are given here, from the 331-page Tallinn, 1950 edition:

The book is not easily found nowadays, but an augmented edition published in Kharkov in 1999 is still available.

9894. Steinitz and Tarrasch

From page 62 of the book mentioned in C.N. 9884, Introduction to Chess by Christopher Nicole (London, 1973):

‘Wilhelm Steinitz, the first recognized world champion, used to say, “Stall, stall, and then stall some more. Sooner or later your opponent will get an idea, and that idea will smell”.’

We do not know where or when Steinitz ‘used to say’ this, or what grounds I.A. Horowitz had for writing the following on page 27 of the February 1946 Chess Review:

‘... Steinitz, whose famous proverb had suggested the proper strategy: “Stall, stall and stall some more. Your opponent will be sure to get an idea. It will be sure to be rotten, and you will win.”’

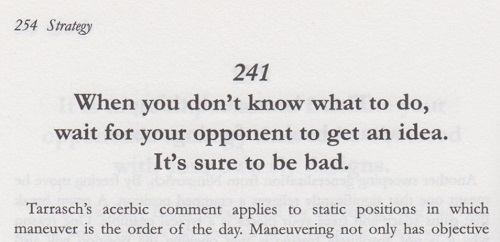

Tarrasch is also mentioned in this connection, e.g. on

page 254 of

Naturally no source was given.

9895. Sam Loyd and money

From page 364 of the Dubuque Chess Journal, September 1875, at the end of an article on Sam Loyd:

‘Outside of the chess world, Mr S. Loyd has made himself famous by the construction of advertising puzzles, such as pictures of trick mules on moveable cards, and various ingenious toys; from which patented and copyrighted trifles he has, we understand, accumulated a comfortable living and quite a fortune.’

After referring to this on pages 263-264 of the October 1875 City of London Chess Magazine, W.N. Potter commented:

‘We are glad to hear of such being the case; brains outside of chess are, nowadays, a valuable marketable commodity. There are some enthusiasts who imagine the advent of a time when, in the limits of the game, superior intelligence will be profitable. We do not share their views. Caissa, we feel assured, will never have any niche in the Temple of Mammon, nor are we clear that this is any matter worth whining at.’

9896. Taubenhaus v

Vázquez match (C.N. 9887)

Thanks to assistance from Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA), Patsy A. D’Eramo (North East, MD, USA), Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) and Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore), all ten games in the 1894-95 match in Havana between Jean Taubenhaus and Andrés Clemente Vázquez have now been found. They are given in our latest feature article.

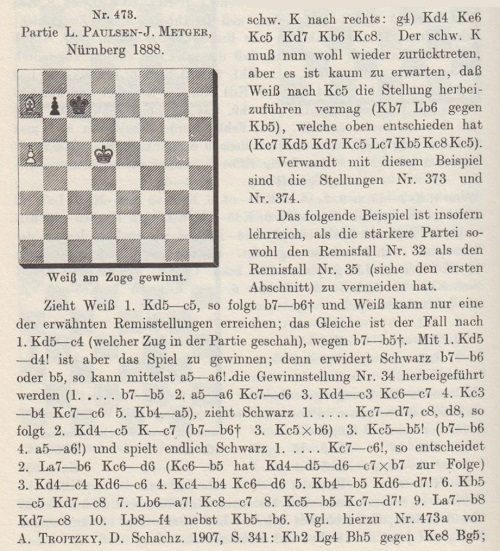

9897. A bishop ending

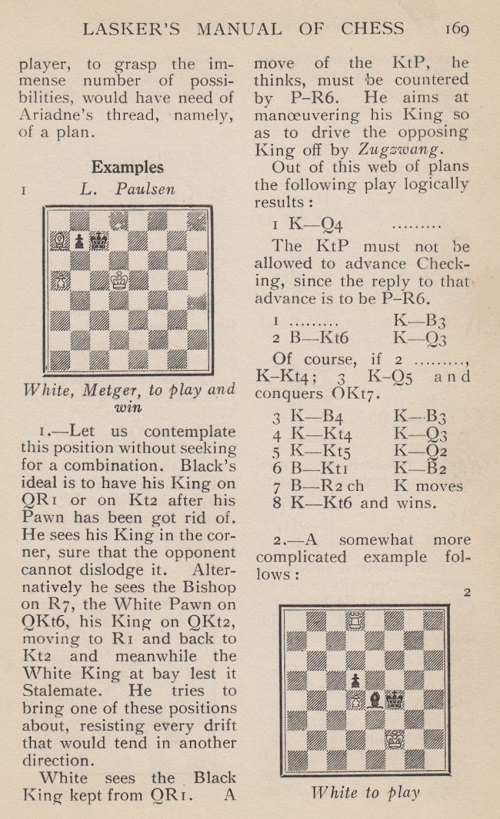

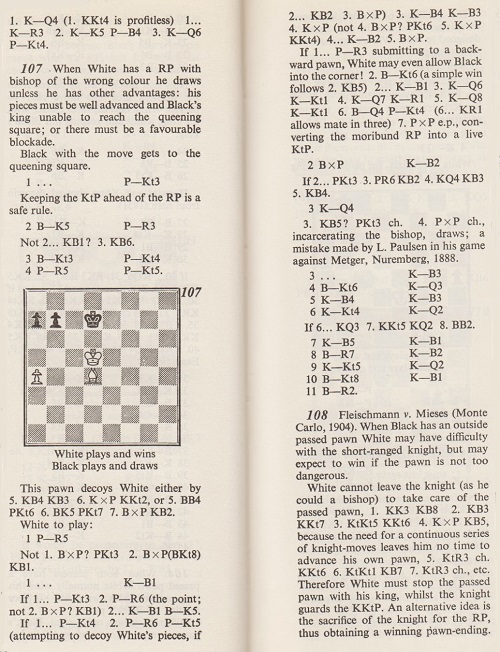

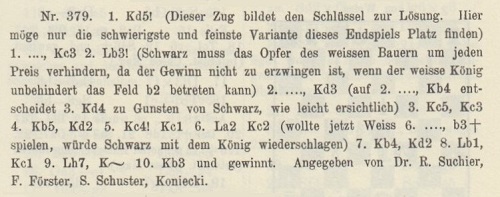

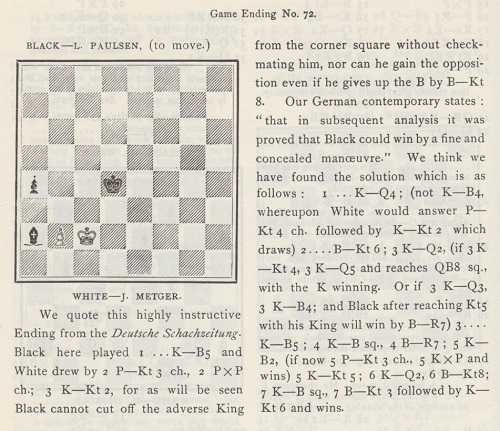

Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) asks about an ending on page 169 of Lasker’s Manual of Chess by Emanuel Lasker (London, 1932):

Our correspondent notes that additional information on this widely published position was given on pages 66-67 of A Guide to Chess Endings by Max Euwe and David Hooper (London, 1959):

Noting the discrepancy over, in particular, the players’ colours, Mr Rhéaume enquires whether the full game-score is available.

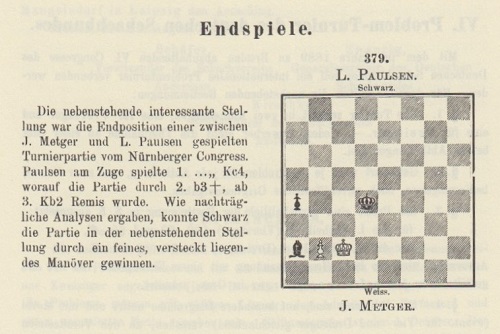

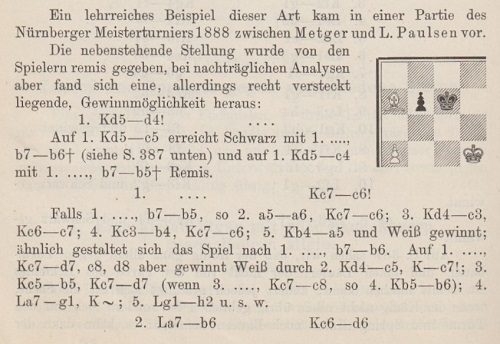

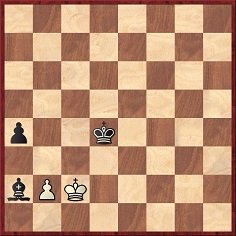

We have yet to find it, but the ending was published on page 285 of the September 1888 Deutsche Schachzeitung, with the solution on page 103 of the April 1889 issue:

On page 316 of the October 1888 International Chess Magazine Steinitz wrote:

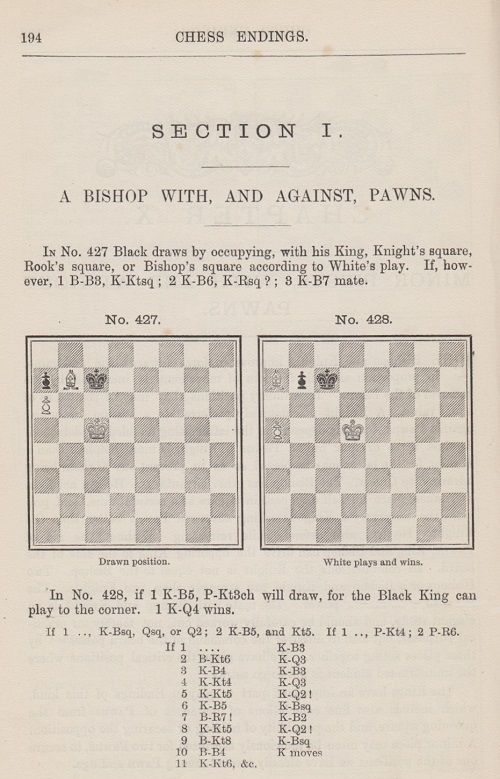

From page 502 of Theorie und Praxis der Endspiele by Johnann Berger (Berlin and Leipzig, 1922):

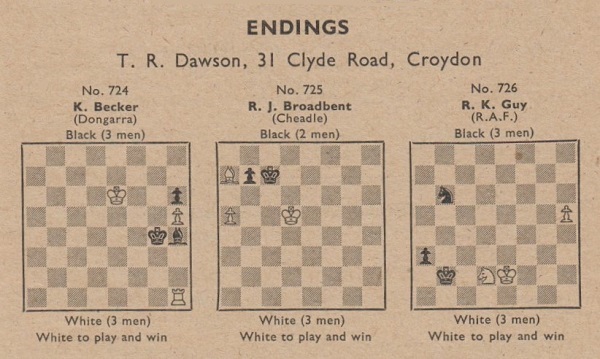

Inexplicably, the position was attributed to R.J. Broadbent on page 57 of the February 1946 BCM:

Dawson’s ‘Endings’ column had further information in subsequent issues:

- March 1946, pages 92-93: The solution, beginning 1 Kd4.

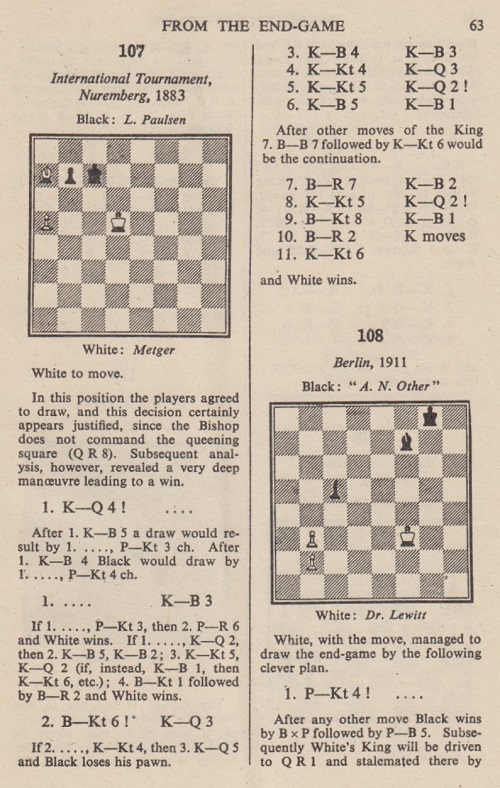

- April 1946, page 120: G.W. Moses pointed out that the position was identical to one in J. Mieses’ Instructive Positions from Master Chess. Below is page 63 of that book (London, 1938):

The date ‘1883’ should read 1888.

- May 1946, page 156: M. Knibbs reported that the position was the conclusion of the game Paulsen v Metzer [sic], Nuremberg, 1888.

- June 1946, page 191: L. Murray noted that the conclusion was also in Chess Endings by E. Freeborough (London, 1891):

- July 1946, page 222: ‘It is interesting to learn from the veteran master J. Mieses that he watched Metger and Paulsen agree to a draw in this position in Nuremberg, 1888 and that he and Dr Tarrasch immediately afterwards discovered the win by 1 K-Q4, published the same year in the D. Sz., he believes, as well as in his Lehrbuch in 1894.’

From pages 436-437 of Lehrbuch des Schachspiels by C. von Bardeleben and J. Mieses (Leipzig, 1894):

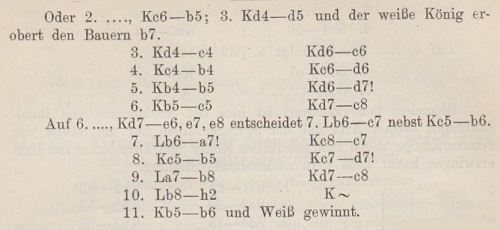

As shown by the crosstable on page 264 of the September 1888 Deutsche Schachzeitung, Nuremberg, 1888 was a double-round tournament in which Paulsen scored a win and a draw against Metger:

The essentials concerning the position were clarified nearly 50 years ago. See, for instance, D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column on page 105 of the April 1968 BCM, which had a detailed note by A.J. Roycroft from EG, January 1968, translated from the 8-9/1967 Deutsche Schachzeitung (research by Egbert Meissenburg). What more can be found about the play between Metger and Paulsen at Nuremberg, 1888?

9898. W.N. Potter

on chess and women

Pages 253-254 of the September 1875 City of London Chess Magazine gave, with ‘notes by A. Burn, Jun.’, the well-known Gilbert v Berry game (1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Nxe4 6 Re1 Nc5 7 Bxc6 dxc6 8 d4 Ne6 9 dxe5 Qe7 10 Nc3 Bd7 11 a4 O-O-O 12 b3 f6 13 Qe2 Qf7 14 Ne4 Rg8 15 c3 h6 16 b4 f5 17 Ng3 g5 18 Nd4 Nxd4 19 cxd4 Re8 20 b5 cxb5 21 axb5 Bxb5 22 e6 Qg6 23 Qxb5 f4 ‘and White announced mate in 19 moves’) courtesy of the Hartford Times. The game prompted some general comments on women’s chess on pages 227-228 of the same issue of Potter’s magazine:

‘We present this month a correspondence game – taken by us from the Hartford Times – between Mrs Gilbert, of Hartford, Connecticut, the strongest lady player in the United States, and Mr Berry, of Beverly, Massachusetts, in which the former announces a mate in 19 moves. The immeasurable superiority of trousers chess is often vaunted, and the natural incapability of women for excellence in the game is deduced from certain propositions, any one of which is a fact taken for granted, though neither self-evident nor demonstrable. The strength of men’s prejudices and of their boot-holding extremities are [sic] generally about on a par, and very often they cooperate. Their physical superiority they use first as a force, and then as an argument. Excluding the ladies by the rule of fist from clubs and associations, discouraging their home play, and pooh-poohing their first timid efforts, the masculine countenance then lights up with an idiotic grin which seconds the enunciation. “Women play? Can’t do it, sir; Nature wills otherwise. Let them cook and sew, that’s what they can do, sir.” Very much would we like to get hold of one of these oracles, place before him the position in which Mrs Gilbert announced “checkmate in 19 moves”, and ask him to find out how it was to be done. If, moreover, we could extract from him a pledge that he would not dine until he had solved it, then our cup of happiness would be overflowing, for we should have delicious visions of many dinnerless days as the just punishment of irrational prejudication. There is this further to be said, that to study a position when you are told there is a mate in 19 moves is quite a different thing from conceiving the idea of it in the first instance, and then working up the possibility into a certainty. Mrs Gilbert says that it was one of the severest intellectual tasks she ever attempted. We have no doubt of it, especially in a case like the present, where the defence is not forced to a particular line of play. The human mind with difficulty grasps such a succession of sequences, even with the solution given, and such an achievement in one of the depreciated female sex ought to have two effects – shake the prejudices of men and create self-confidence in women. We should like to see chess become more general among the latter. Why should it not be a common thing for a man and wife to have a game before going to rest? Much more companionable and reasonable, we should say, than the one soaking his brains with numerous nightcaps, while the other spends a listless half-hour unpinning her back hair and counting her spoons.’

9899. Mate with two knights

Two further quotes from Introduction to Chess by Christopher Nicole (London, 1973), the book mentioned in C.N.s 9884 and 9894, come from pages 32 and 73:

‘He cannot ever checkmate you with two knights.’

‘At the beginning of this book I mentioned that it is impossible to give checkmate with a pair of Kts.’

This mistake (‘impossible to give’ rather than ‘impossible to force’) has often been committed. Particularly early, recent or surprising citations will be welcome.

9900. Reinfeld on Alekhine

From page 104 of How to Play Winning Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1962):

‘Yet, for all his daring at the chessboard, he was burdened with strangely timorous quirks of character. After fleeing from Russia in 1921 he had lived in great poverty for some time in Germany. This harrowing period left a lifelong mark on him. I can vividly recall meeting him for the first time at the Pasadena tournament of 1932, for my naive hero-worshiping attitude was jarred by some of his strange whims. For example, although he was virtually a chain-smoker, he always kept his cigarettes in his pocket. When he wanted to smoke, he would reach into his pocket and maneuver one cigarette out without removing the pack. In this way he avoided the social necessity of offering his companion or opponent a cigarette.’

9901. The Maróczy Bind (C.N. 8545)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) notes that when the Maróczy v Voigt game given in C.N. 8545 was published on page 2 of the Philadelphia Inquirer, 29 April 1906, the following assertion came after 1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Nf3 g6 4 Nxd4 Bg7 5 c4:

‘This is Mr Maróczy’s new move, and he is so sure that it gives White a great advantage that he offered to give Dr Tarrasch five games out of ten if the doctor would play the variation taking the black pieces. The doctor, however, declined.’

9902. A bishop ending (C.N. 9897)

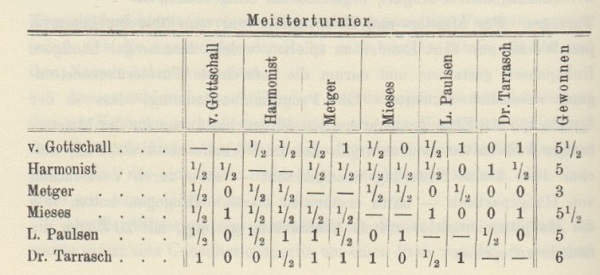

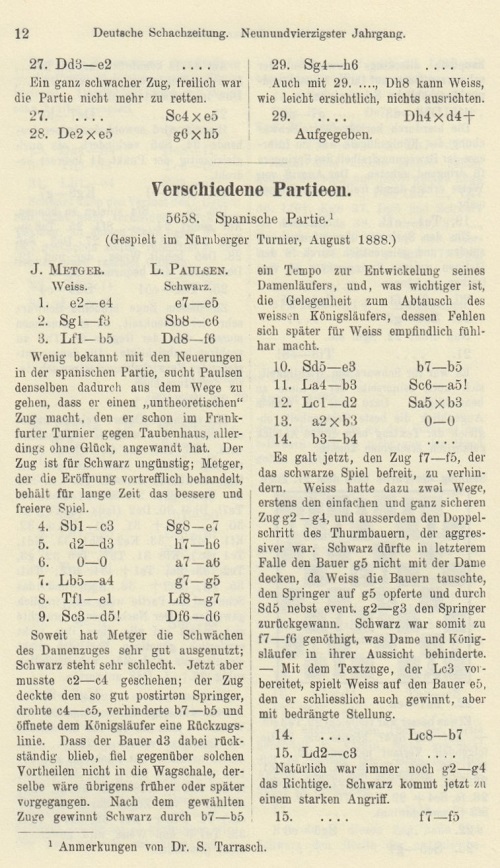

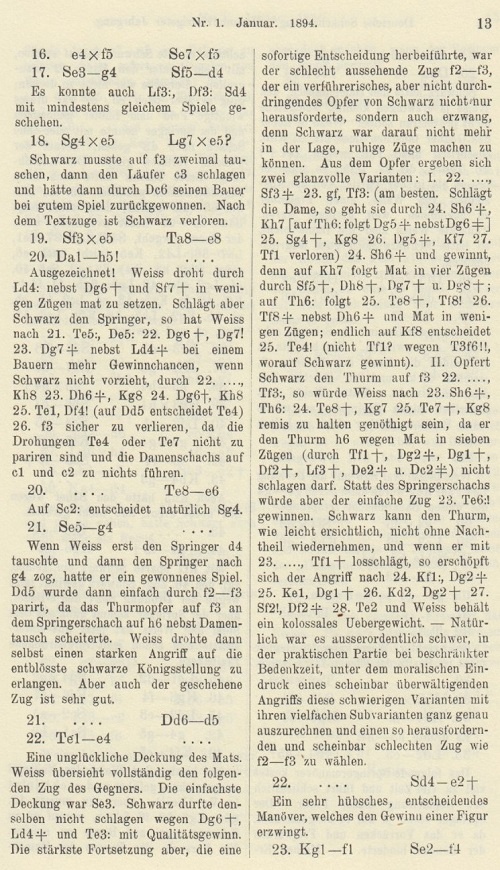

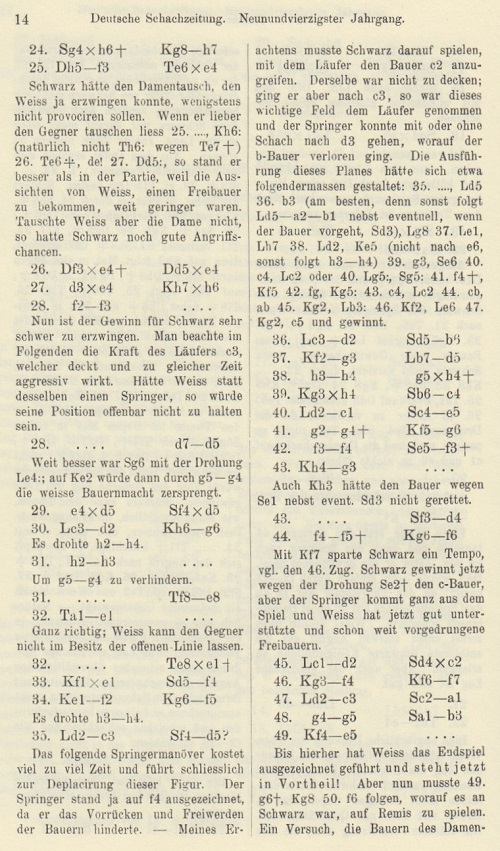

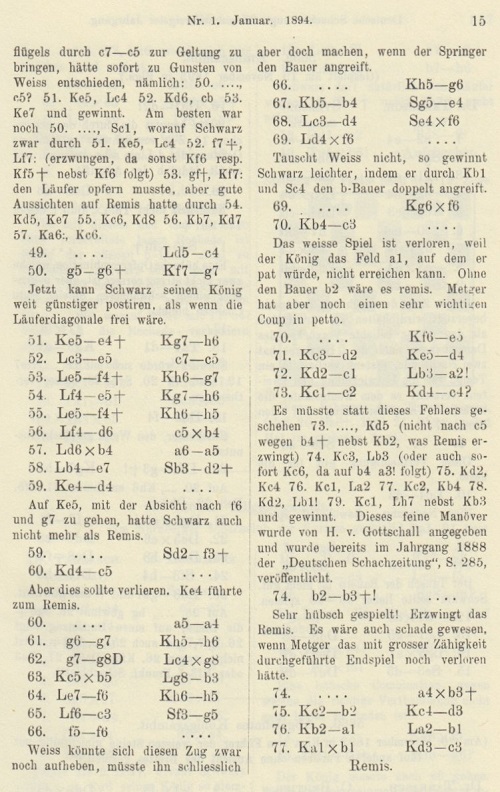

Mr Bauzá Mercére has also found that many years after the Metger v Paulsen game was played it was published on pages 12-15 of the January 1894 issue of the Deutsche Schachzeitung, with notes by Tarrasch (which include a credit to Hermann von Gottschall for indicating the 73...Kd5 line in 1888):

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Qf6 4 Nc3 Nge7 5 d3 h6 6 O-O a6 7 Ba4 g5 8 Re1 Bg7 9 Nd5 Qd6 10 Ne3 b5 11 Bb3 Na5 12 Bd2 Nxb3 13 axb3 O-O 14 b4 Bb7 15 Bc3 f5 16 exf5 Nxf5 17 Ng4 Nd4 18 Ngxe5 Bxe5 19 Nxe5 Rae8 20 Qh5 Re6 21 Ng4 Qd5 22 Re4 Ne2+ 23 Kf1 Nf4 24 Nxh6+ Kh7 25 Qf3 Rxe4 26 Qxe4+ Qxe4 27 dxe4 Kxh6 28 f3 d5 29 exd5 Nxd5 30 Bd2 Kg6 31 h3 Re8 32 Re1 Rxe1+ 33 Kxe1 Nf4 34 Kf2 Kf5 35 Bc3 Nd5 36 Bd2 Nb6 37 Kg3 Bd5 38 h4 gxh4+ 39 Kxh4 Nc4 40 Bc1 Ne5 41 g4+ Kg6 42 f4 Nf3+ 43 Kg3 Nd4 44 f5+ Kf6 45 Bd2 Nxc2 46 Kf4 Kf7 47 Bc3 Na1 48 g5 Nb3 49 Ke5 Bc4 50 g6+ Kg7 51 Ke4+ Kh6 52 Be5 c5 53 Bf4+ Kg7 54 Be5+ Kh6 55 Bf4+ Kh5 56 Bd6 cxb4 57 Bxb4 a5 58 Be7 Nd2+ 59 Kd4 Nf3+ 60 Kc5 a4 61 g7 Kh6 62 g8(Q) Bxg8 63 Kxb5 Bb3 64 Bf6 Kh5 65 Bc3 Ng5 66 f6 Kg6 67 Kb4 Ne4 68 Bd4 Nxf6 69 Bxf6 Kxf6 70 Kc3 Ke5 71 Kd2 Kd4 72 Kc1 Ba2 73 Kc2

73...Kc4 74 b3+ axb3+ 75 Kb2 Kd3 76 Ka1 Bb1 77 Kxb1 Kc3 Drawn.

9903. Quiz question

Which annotator gave the move ...Qe2 mate in both of these positions?

9904. Austrian postage stamps

Another stamp in the Austrian series (see C.N.s 3680, 3681 and 3689, as well as Chess and Postage Stamps) had a well-known photograph of Rubinstein and Mieses:

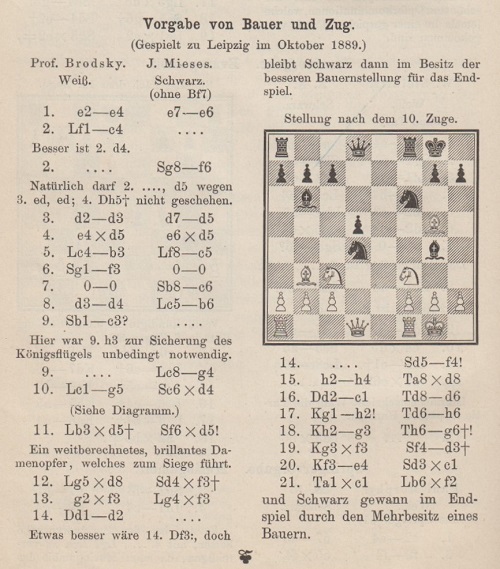

9905. Brodsky v Mieses

From page 480 of Lehrbuch des Schachspiels by C. von Bardeleben and J. Mieses (Leipzig, 1894):

(Remove Black’s f-pawn.) 1 e4 e6 2 Bc4 Nf6 3 d3 d5 4 exd5 exd5 5 Bb3 Bc5 6 Nf3 O-O 7 O-O Nc6 8 d4 Bb6 9 Nc3 Bg4 10 Bg5 Nxd4 11 Bxd5+ Nxd5 12 Bxd8 Nxf3+ 13 gxf3 Bxf3 14 Qd2 Nf4 15 h4 Raxd8 16 Qc1 Rd6 17 Kh2 Rh6 18 Kg3

18...Rg6+ 19 Kxf3 Nd3+ 20 Ke4 Nxc1 21 Raxc1 Bxf2 and wins.

The conclusion (‘Stellung aus einer im October 1889 zu Leipzig gespielten Partie’) was published on page 55 of the Deutsche Schachzeitung, February 1890. The moves from ...Nxd5 to ...Rd6 were on page 21 of Meister Mieses by Helmut Wieteck (Ludwigshafen, 1993). A wrong date (1890) was given.

9906. Bust of Capablanca (C.N.s 6583 & 7803)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) notes at the Gallica website a fine version of the photograph discussed in C.N.s 6583 and 7803.

9907. London, 1927

A shot of Wolf and Terho was presented in C.N. 7981, but it is strangely difficult to find photographs taken during the International Team Tournament in London, 1927.

9908. Alekhine v Sánchez (C.N.s 5436 & 5440)

From Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina):

‘Luis Augusto Sánchez Montenegro was born in Neiva (Colombia) on 20 July 1917 (El Tiempo, 22 February 1969, page 18) and died on 20 April 1982 (El Tiempo, 22 April 1982, page 4-A). He won the chess championship in the first Bolivarian Games, which took place in Bogotá (Colombia) on 10-20 August 1938 (El Tiempo, 21 August 1938, page 9).

The Bolivarian Games are a sports event, similar to the Olympic Games, in which countries liberated by Simón Bolívar can participate (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, Peru and Venezuela).

Alekhine played Sánchez on 21 March 1939 in a simultaneous exhibition in Bogotá (El Tiempo, 22 March 1939, page 1). The game lasted 28 moves, and not 25 as the known score indicates.

Thus Alekhine won against the Bolivarian champion (“campeón bolivariano”), i.e. the champion of the Bolivarian Games, and not the “Bolivian” champion (“campeón de Bolivia”) as stated in his posthumous book Gran Ajedrez.’

9909. Joseph Brown

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘In my 2011 book Notes on the Life of Howard Staunton, brief mention was made on page 41 of one of Staunton’s early opponents, “J. Brown, QC”, who was identified as Joseph Brown, a barrister of the Temple. The obituary of Staunton which appeared in the Westminster Papers (1 August 1874, pages 61-63) referred to Brown in the course of some remarks about Staunton’s early chess career:

“... and he was also a frequent habitué of the ‘Shades’, in the basement of old Saville House, Leicester Square, which was at one time the headquarters of London chess, and where, if we mistake not, he contested some of his best games with Mr J. Brown, QC – one of the most accomplished amateurs of the day – and the veteran, Mr Cochrane.”

This referred to events more than 30 years earlier. A rough time-frame for Staunton’s games with “Mr J. Brown, QC” can be gauged from their appearance in volume two of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, which contained a number of games between Staunton and both the above opponents. If the games against Brown were recent – as were those with John Cochrane – they were played in the last months of 1841. Staunton continued to play against Cochrane until the Spring of 1843, when the latter returned to India.

The forename Joseph of the chessplayer “J. Brown, QC” was revealed in chess literature on a limited number of occasions, one being a chance remark in an obituary of Horace Lloyd, QC published on page 15 of the Westminster Papers, 1 May 1874:

“At chess he was a strong amateur, and used to play at the Divan in the days when Joseph Brown, QC did not disdain to amuse himself, and Buckle would sit for eight hours at hard play, and call this relaxation.”

The Westminster Papers (April 1868, page 8) provided a reference to J. Brown, QC as someone “requested to act” as a committee member of the re-embodied Westminster Chess Club at a meeting held on 8 June 1866:

“2nd. Proposed by Mr Morris, seconded by Mr De Vere – ‘That Messrs Barnes, H.E. Bird, S.S. Boden, J. Brown, QC, F. Burden, P.T. Duffy, T. Hewitt, Dr Ingleby, H. Staunton and C. Walsh, be requested to act on the committee of the new Club.’”

This time the events mentioned were not so distant in the past. The Law List for 1866 records (on page 18) only one QC by the name of J. Brown: Joseph Brown, QC of 2 Essex Court, Temple. Similarly, Joseph Brown, QC of 2 Essex Court, was the only possible J. Brown, QC in The Law List for 1874, on page 22. The Law List for 1841 contains no J. Brown, QC, the reason being that Joseph Brown did not take silk until 1865, but it does have, on page 67, an entry for Joseph Brown, Esq., of 2 Essex Court, Temple, under “Certificated Special Pleaders”. (Editions of The Law List for 1842, 1868 and 1875 contain entries which endorse those noted above.)

From the foregoing it is evident that the Staunton obituary in the Westminster Papers referred to this player as “Mr J. Brown, QC” out of respect for his status at the time of writing rather than at the time he played against Staunton, in the early 1840s.

The 1 August 1868 issue of the Westminster Papers also had an article with reminiscences of the 40 years during which Ries’ Divan in the Strand had been frequented by notable chessplayers. The writer mentioned, on page 51, “that black-lettered lawyer, Joe Brown”:

“This establishment (an old friend in itself) introduced us to many of our most pleasant acquaintances and best friends. Here, first, we met that black-lettered lawyer, Joe Brown. Here, Staunton, Mundell, Barnes and Lavies, all charming companions, and first-rate conversationalists.”

That Joseph Brown was known as “Joe Brown” is corroborated by an obituary of him on page 1 of the Cheltenham Chronicle, 14 June 1902. It related that he was …

“ ... known with respect and admiration as ‘Joe Brown’ …”

However, the “Personal Gossip” column on page 3 of the Gloucester Citizen of 11 June 1902 suggested a different variation, “Joey Brown”, and in so doing presented an example of his brand of humour:

“All the accounts of the late Mr Joseph Brown, KC, says the Daily Chronicle, make the mistake of stating that he was always known as Joe Brown; he was always known as ‘Joey’ Brown, from a playful habit of signing himself 4½d – the fourpenny piece five-and-twenty years ago was known as a Joey, and the brown as a halfpenny.”

Joseph Brown was born on 4 April 1809 in the parish of Newington, Surrey, the son of Joseph Brown, a wine merchant, and his wife, Charlotte, and was baptized on 27 April 1810 in the Surrey Chapel, Blackfriars Road, Southwark, which was a Nonconformist chapel belonging to the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion (National Archives, RG 4/4214, page 63).

Because he became an eminent lawyer, certain details of his long life are in print. His obituary in the Times of 10 June 1902 (page 12) states that, having been educated, successively, by his uncle, Rev. John Whitridge, of Carlisle, at the Grammar School at Camberwell, and at Mr Fennell’s school in Wimbledon, he spent two years in the office of Messrs Armstrong and Co., West India merchants, and then for some time was in the office of Peter Turner, a City solicitor.

The Dictionary of National Biography states that he obtained a B.A. and M.A. at Queens’ College, Cambridge, but that seems doubtful, being contradicted by John Venn’s Alumni Cantabrigienses, in which the Cambridge graduate Joseph Brown is identified as a clergyman.

His father died in 1831, whereupon his will was proved in London on 15 November 1831, describing him as a wine merchant of Laurence Pountney Lane, London, and Camberwell, Surrey (National Archives, PROB 11/1791B, f. 121). Shortly after his father’s death Joseph Brown was admitted to the Middle Temple. Register of Admissions to the Middle Temple has the following record of an admission on 12 January 1832:

“Joseph Brown, second son of Joseph B., late of Camberwell, Surrey, Esq., decd. Called 7 November 1845. Bencher 9 May 1865. Reader Lent 1869. Treasurer 1878.”

When Joseph Brown played chess with Howard Staunton in 1841-42, it was before he had been called to the Bar on 7 November 1845. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, he had become a special pleader under the Bar in 1834, and learned the art of special pleading while under Sir William Henry Watson and Sir John Bayley. He was listed in contemporary London directories as a special pleader. For example, Pigot and Co.’s Directory of London, September 1839 (page 68) contains an entry for ...

“... Brown Joseph, special pleader, 2 Essex Court, Temple.”

Similar entries in the Post Office London Directory, 1845 (pages 125 and 574) show that that was still his business address at the time, but that his private address was 17 Bedford Row, Islington.

In the parish church of Winchcombe, Gloucestershire he had married, on 24 August 1840, Mary Smith, daughter of Thomas Smith, “gentleman”. His bride was slightly older, having been baptized at Winchcombe on 28 December 1807. She had a brother, William, who was baptized there on 18 October 1811. Joseph and Mary had three sons and two daughters.

The 1841 census (National Archives, HO 107 665/2, f. 11) described Joseph Brown as a “special pleader” at Bedford Row, Islington, with his wife, Mary. In the same household was William Smith, aged 29, a man of independent means, who is taken to be Mary’s brother. It appears that William Smith also became a chessplayer, since a man of that name, of Winchcombe, appears on page 142 in the list of subscribers to Elijah Williams’ book Souvenir of the Bristol Chess Club (London, 1845), in addition to the following entry on page 139:

“Brown, Joseph, Esq. Temple, London.”

The use of abbreviations for the names of players and problemists in the Chess Player’s Chronicle makes it harder to assemble a complete, reliable list of references to Joseph Brown. However, in view of his longstanding professional attachment to the Temple, it seems safe to associate with him, as a minimum, any material in which the abbreviation “J----- B----, Temple” or “J----- B---n, Temple” (with or without “Mr”) was used. Joseph Brown, or J. Brown, of the Temple, with or without abbreviation, became the way he was usually styled in his chess activities.

The first known mention of him in chess literature came in early Autumn 1841, not as a player but as a problem composer, when a problem by “J----- B----, Temple” appeared on page 369 of the first volume (1841) of the Chess Player’s Chronicle. Shortly afterwards, another composition by him, on page 382, was praised by Staunton as a “masterly stratagem”:

White to mate in ten with the pawn on g5 without capturing either of Black’s pawns

Solution: 1 Ke5 Kg8 2 Qd8+ Kf7 3 h5 gxh5 4 Qf8+ Kg6 5 Qf4 h4 6 Qf5+ Kh5 7 g6+ Kxh6 8 Bd2+ Kg7 9 Qf7+ Kh8 10 g7 mate.

Only a few pages earlier, on pages 373-374, had appeared Staunton’s first game with Cochrane. Staunton’s obituary in the Westminster Papers mentioned Brown in the same breath as Cochrane, a barrister called to the Bar at the Inner Temple on 29 June 1824. It is very likely that the two lawyers knew each other, and it seems possible that it was through John Cochrane that Staunton met Joseph Brown.

Compositions by Joseph Brown continued to appear in volume two of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, including eight problems on diagrams on pages 30, 33, 49, 93, 145, 158, 225 and 289. It is uncertain whether he was also the author of seven others in the series of “Problems for young players”; these were printed on pages 101, 172, 187, 205, 217, 235 and 249 of the same volume.

Today Joseph Brown is almost forgotten as a problemist. Any lingering chess fame hinges rather on his association with Howard Staunton. He can be identified as Staunton’s opponent in ten published games. These were printed in the Chess Player’s Chronicle, volume two, on pages 49-51, 51-52, 65-67, 97-98, 98-99, 113-115, 165-166, 193-195, 209-210 and 210-211. That “B---n” stood for “Brown” was later confirmed on pages vii and 41 of Staunton’s book The Chess-Player’s Companion (London, 1849), where the same ten scores were printed with annotations as games XXXVII to XLVI on pages 41-56. On page 41, “Mr J. Brown” was referred to as “one of the finest Metropolitan amateurs”, which is compatible with the description, “one of the most accomplished amateurs of the day”, which was applied to J. Brown, QC in the obituary of Staunton in the Westminster Papers.

In every game Staunton gave the odds of pawn and two moves, and won a majority of five to three, with two draws. The venue of the first game, Goode’s (39 Ludgate Hill, London) is not the same as the “Shades”, which was mentioned in Staunton’s obituary. The same consideration applies to Staunton’s games against Cochrane, for which Goode’s was the only venue mentioned at the time. It is possible that both venues were used. The first mention of the “Shades” in the Chess Player’s Chronicle does not occur until page 191 of volume two, when Staunton noted that he had recently seen (rather than played) some games there.

Volume two of the Chess Player’s Chronicle also printed, on pages 246, 258-259, 273-274, 292-293, 305-307 and 307-308, the scores of six games “in a match between Messrs J----- B---n and S-----y”. It is tempting, but not sufficiently safe, to identify the players as Joseph Brown and Charles Henry Stanley, the future American champion, given that those abbreviations were used for them elsewhere and both were active players in the same place, i.e. London, at the same time; since they had received the same odds of pawn and two from Staunton, they may have been considered a suitable match. Of the published games J----- B---n won four and lost two.

The Middle Temple had at least one other very fine chessplayer, Thomas Wilson Barnes. Born in Armagh, Northern Ireland, he had obtained his M.A. at Trinity College, Dublin in the summer of 1851 (source: Alumni Dublinenses, 1924, page 41) before being called to the Bar on 8 June 1852. He became one of the strongest amateurs of his day, winning casual games against Paul Morphy. Another barrister of the Middle Temple, though not, as far as is known, a chess proficient, was Richard Brinsley Knowles (1820-82), who was called to the Bar on 26 May 1843. He must have known Joseph Brown. An author and dramatist, Knowles edited the Illustrated London Magazine from 1853 to 1855. For a short time, Elijah Williams edited a chess column for the magazine, and on page 141 of volume one (1853) he annotated a game in which he played the white side of a Queen’s Gambit Declined against “Joseph Brown, Esq.”. It was a long game, eventually won by Williams. Earlier, on page 96, in an introduction to Williams as the chess editor, the following statement had been made:

“In each month he will supply the latest games of any interest played by the best players.”

This makes it seem possible that the game against Brown was fairly recent. If so, Brown’s ability to compete against the winner of the third prize at the 1851 London international tournament without receiving odds would suggest that he retained the reputation of being a strong player as late as 1853.

An earlier game between the two had appeared on pages 126-127 of Williams’ 1852 book Horæ Divanianæ:

Elijah Williams – Joseph Brown

Occasion?

Scotch Gambit1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Bc4 Qf6 5 O-O d6 6 c3 d3 7 Ng5 Ne5 8 f4 Nxc4 9 Qa4+ Bd7 10 Qxc4 O-O-O 11 e5 Qf5 12 Qxf7 Nh6 13 Qxf5 Bxf5 14 h3 dxe5 15 g4 Bc5+ 16 Kh2 Bxg4 17 hxg4 Nxg4+ 18 Kg3 Ne3 19 Bxe3 Bxe3 20 Nf7 Bxf4+ 21 Kg2 g5 22 Nxh8 Rxh8 23 c4 e4 24 Nc3 e3 25 Rae1 Re8

26 Kf3 h5 27 Rh1 e2 28 Rxh5 Bd2 29 Rxe2 g4+ 30 Kf2 g3+ 31 Kf3 dxe2 32 Nxe2 Re3+ 33 Kg2 Rxe2+ 34 Kxg3 Be1+ 35 White resigns.

The list of subscribers to Horæ Divanianæ includes on page 173:

“Brown, Joseph, Esq., Temple”

Later, this game was given in the Chess Player’s Chronicle, December 1870, pages 180-182, where Black was identified as “Mr J. Brown, QC”. The date of the game is not known, and it may have been well before Williams reached his full strength. The same consideration applies, only much more so, to ten games between Elijah Williams and J. Brown, “one of the best Metropolitan players”, which had previously appeared in Williams’ Souvenir of the Bristol Chess Club in 1845. These games were numbered LXXI to LXXX on pages 91-105, and Williams won six to Brown’s three, with one drawn.

In another game, published on page 155 of volume eight of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1847, Williams won against Brown on the black side of a French Defence Exchange Variation.

It is uncertain whether Elijah Williams’ opponent was Joseph Brown in six other games, played by him against “Mr B---n”, which had previously been published in volume three of the Chess Player’s Chronicle on pages 291-297. If it were confirmed, it would mean that the two had played each other as early as 1842. Of the six, Williams won two and lost one, with three draws.

Joseph Brown’s legal activities naturally focused on his commercial practice, which was prosperous. His obituary in the Times considered him “industrious and learned, rather than brilliant”. He was the author of several legal titles, the best known perhaps being The Dark Side of Trial by Jury (1859). His entry in the Dictionary of National Biography indicates that he “had a wide-ranging intellect and interests”, including geology and numismatics. Evidently he chose to keep a low profile as a chessplayer, but, in any case, there are no obvious signs of his having played after his mentions by Williams. His being asked to serve on the committee of the Westminster Chess Club in 1866 may appear to be an exception to this chess inactivity, but it is not clear whether he accepted the invitation, since his name is not included in the list of the committee printed in the second edition of Rules and Regulations of the Westminster Chess Club (1867).

Brown survived until the age of 93, which was long enough to see his QC become KC after the accession of King Edward VII. The National Probate Calendar shows that he died on 9 June 1902 at 54 Avenue Road, Regent’s Park, London, his effects amounting to a healthy £85,126 7s. 11d.’

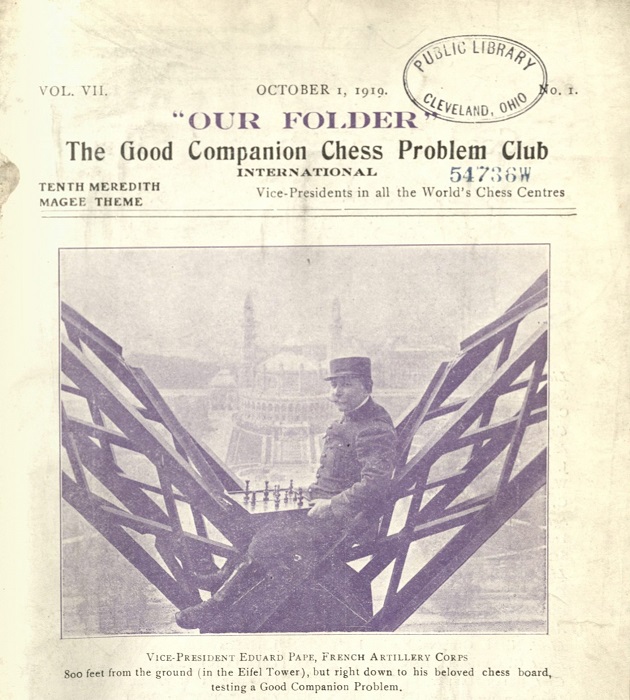

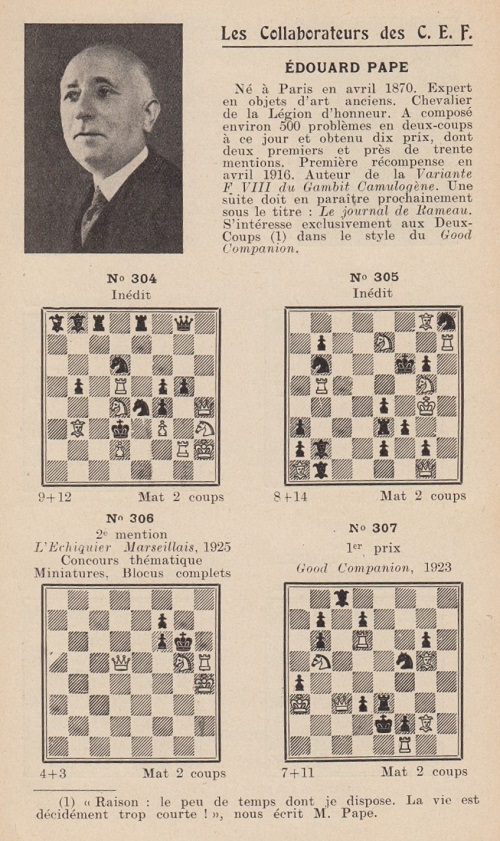

9910. Edouard Pape (C.N. 4119)

C.N. 4119 gave a photograph of Edouard Pape (1870-1949), and we are now grateful to the Cleveland Public Library for providing its earlier appearance, on page 1 of “Our Folder” (The Good Companion Chess Problem Club), 1 October 1919:

A feature about Pape on page 27 of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français, January-February 1935:

9911. Capablanca in 1921

This portrait has been found by Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) on page 394 of Cine-Mundial, June 1921:

9912. Fischer-Spassky chit-chat

To write about the 2016 ‘Karjakin-Carlsen’ match would be odd and, even, discourteous to the defending champion, yet most of us have, at least occasionally, referred to the ‘Fischer-Spassky’ match of 1972. Alphabetical order and the identity of the winner cannot explain this, because the 1927 world title match is usually, and properly, termed ‘Capablanca-Alekhine’. Fischer’s profile in 1972 was so high, often for woeful reasons, that it is tempting to name him first even though he was the challenger, but a linguistic point also arises. From pages 39-40 of The Elements of Eloquence by Mark Forsyth (London, 2013), in the chapter on hyperbaton:

‘Have you ever heard that patter-pitter of tiny feet? Or the dong-ding of a bell? Or hop-hip music? That’s because, when you repeat a word with a different vowel, the order is always I A O. Bish bash bosh. So politicians may flip-flop, but they can never flop-flip. It’s tit-for-tat, never tat-for-tit. This is called ablaut reduplication, and if you do things any other way, they sound very, very odd indeed.’

Thus in British politics in the late 1970s, the term ‘Lib-Lab pact’ was used despite the Liberal Party being far smaller than the governing Labour Party. Even when the consonants in the two elements are different, it may seem more natural for I to precede A. ‘Fischer-Spassky’ is certainly more euphonious than ‘Spassky-Fischer’, but ‘Fischer-Spassky’ may best be reserved for their 1992 match.

9913. Nimzowitsch and tobacco

Mike Salter (Sydney, Australia) notes that another version of the alleged Nimzowitsch anti-smoking incident was related by Carl Ahues in an article, ‘Aus dem reichen Schatz meiner Erinnerungen’, on pages 120-121 of the 8/1954 issue of Schach (‘2. Aprilheft 1954’). From page 120:

‘Hier möchte ich noch eine Anekdote einfügen, die sich im New-Yorker Turnier ereignet haben soll. Nimzowitsch hatte Dr. Vidmar gebeten, während ihrer Partie nicht zu rauchen. Letzterer hatte sich damit einverstanden erklärt, aber mit der Einschränkung, daß er nur dann eine Zigarre nehmen würde, wenn er in eine sehr schlechte Stellung geraten sollte. Das Treffen verlief nikotinfrei, aber Dr. Vidmar gewann! Der verärgerte Nimzowitsch beschwerte sich darauf beim Turnierleiter Maróczy über das “verdammte Rauchen”. “Aber Ihr Gegner hat doch gar nicht geraucht”, war die erstaunte Antwort. “Nicht geraucht? Viel schlimmer als das! Er hat mich mit Rauchen bedroht. Er hatte seine Zigarre neben das Brett gelegt, so daß ich mir sagte: Machst du jetzt einen starken Zug, nimmt er eine Zigarre. Wie kann ich dabei gewinnen! Daß die Drohung stärker ist als die Ausführung, sollten Sie als Schachspieler ja wohl wissen.” – Armer Nimzowitsch! – Wie manche seiner Meisterkollegen war er auch sehr abergläubisch. “Wenn ich eine Partie verliere, ziehe ich mir sofort einen anderen Anzug an”, sagte er einmal zu mir. Übrigens kann ich mich persönlich über ihn kaum beklagen; für mich war er immer ein angenehmer Kamerad.’

9914. Lasker

and Réti

Fine photographs of Emanuel Lasker and Richard Réti are online from the holdings of the National Library of Israel.

9915. Lengthy Reinfeld annotations

A Reinfeld book with two of his longest sets of annotations is A Chess Primer (New York, 1963):

- Pages 81-95: I. Gunsberg v J. Berger, Hamburg, 1885;

- Pages 96-109: L. Tarleton v F. Salzano, Correspondence, 1944.

In each case, Reinfeld reworked notes that he had contributed to the Chess Correspondent (respectively, May-June 1945, pages 6-7 and 20, and March-April 1945, pages 4-5). Since Tarleton v Salzano (‘the deciding game in the last CCLA “B” Championship’) is little known, the score is added here: 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 e3 b6 4 Nbd2 Bb7 5 Bd3 d5 6 O-O Nbd7 7 Re1 Ne4 8 c3 Bd6 9 Qc2 Ndf6 10 Bb5+ c6 11 Bd3 Nxd2 12 Bxd2 Qc7 13 c4 O-O 14 c5 Be7 15 b4 h6 16 e4 dxe4 17 Bxe4 Nxe4 18 Rxe4 Rfd8 19 Rg4 h5 20 Rf4 Bf6 21 g4 hxg4 22 Rxg4 Rd5 23 Bf4 Qd8 24 Bd6 a5 25 Rb1 axb4 26 Rxb4 bxc5 27 Bxc5 Bc8 28 Re4 Rf5 29 Re3 Qd5 30 Rbb3 g6 31 Rec3 e5 32 dxe5 Bxe5 33 Rd3 Bxh2+ 34 Kxh2 Qxc5 35 Rd8+ Kg7 36 Qb2+ Rf6 37 Re3 Qh5+ 38 Kg1 Qg4+ 39 Kh1 Ra5 40 Nh2 Rh5 41 Rg3 Qh4 42 Rg2 Bh3 43 White resigns.

Reinfeld’s book was re-issued by Stein and Day, New York in 1977 with a nine-page introduction by A. Soltis. The following year that edition appeared under the title Chess Basics (Key Book Publishing Company, Toronto).

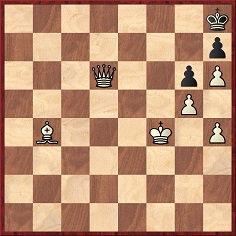

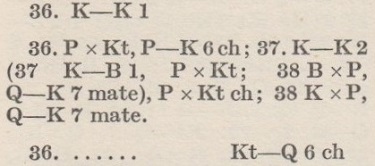

9916. Quiz question (C.N. 9903)

Black to move

C.N. 9903 asked which annotator gave ...Qe2 mate in both the above positions.

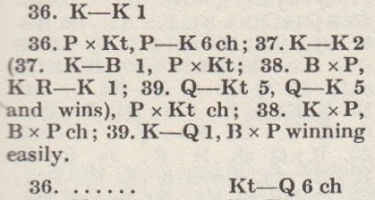

The answer is C.H.O’D. Alexander, in his annotations to Balparda v Alekhine, Montevideo, 1938 on pages 15-17 of Alekhine’s Best Games of Chess 1938-1945 (London, 1949):

The mistake was pointed out in a review on page 5 of the October 1949 CHESS, and the note was amended in subsequent editions:

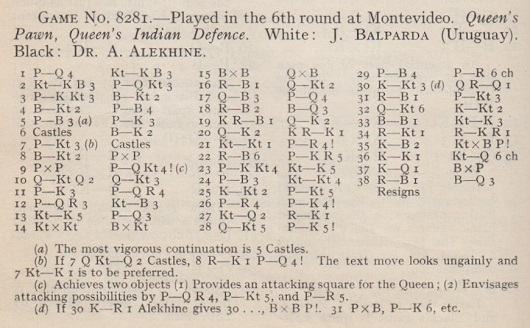

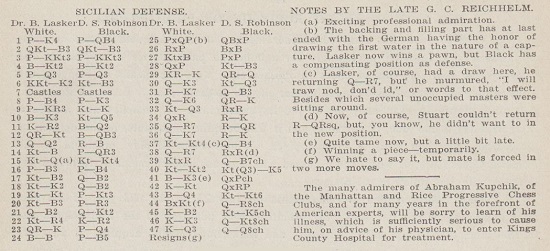

The full score of the Balparda v Alekhine game, which was played in the sixth round of the Montevideo tournament on 14 March 1938: 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 b6 3 g3 Bb7 4 Bg2 c5 5 c3 e6 6 O-O Be7 7 b3 O-O 8 Bb2 cxd4 9 cxd4 b5 10 Nbd2 Qb6 11 e3 a5 12 a3 Nc6 13 Ne5 d6 14 Nxc6 Bxc6 15 Bxc6 Qxc6 16 Rc1 Qb7 17 Qf3 d5 18 Rc2 Bd6 19 Rfc1 Qe7 20 Qe2 Rfb8 21 Nb1 h5 22 Rc6 h4 23 g4 Ne4 24 f3 Ng5 25 Kg2 b4 26 a4 e5 27 Nd2 Re8 28 Qb5 e4 29 f4 h3+ 30 Kg3 Rad8 31 Rf1 g6 32 Qb6 Kg7 33 Bc1 Ne6 34 Rg1 Rh8 35 Kf2 Nxf4 36 Ke1 Nd3+ 37 Kd1 Bxh2 38 Rf1 Bd6 39 White resigns.

The game was published on page 280 of the June 1938 BCM:

We do not know whether the reference to ‘Alekhine gives ...’ in note (d) is based on a written or an oral comment.

The game was annotated by, among others, Santasiere, on page 54 of the May-June 1938 American Chess Bulletin. Showing its customary deep research, the Skinner/Verhoeven book on Alekhine recorded on page 623 that the game had been published in 1938 issues of El Ajedrez Americano, Xadrez Brasileiro and De Schaakwereld. All three gave annotations, and we are grateful to the Royal Library in the Hague for copies of the Brazilian and Dutch periodicals.

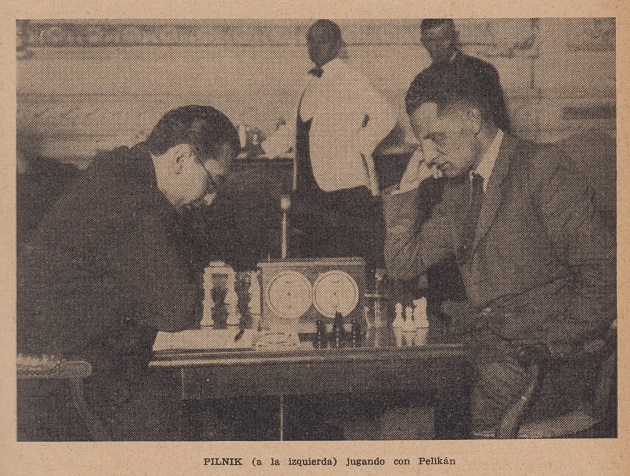

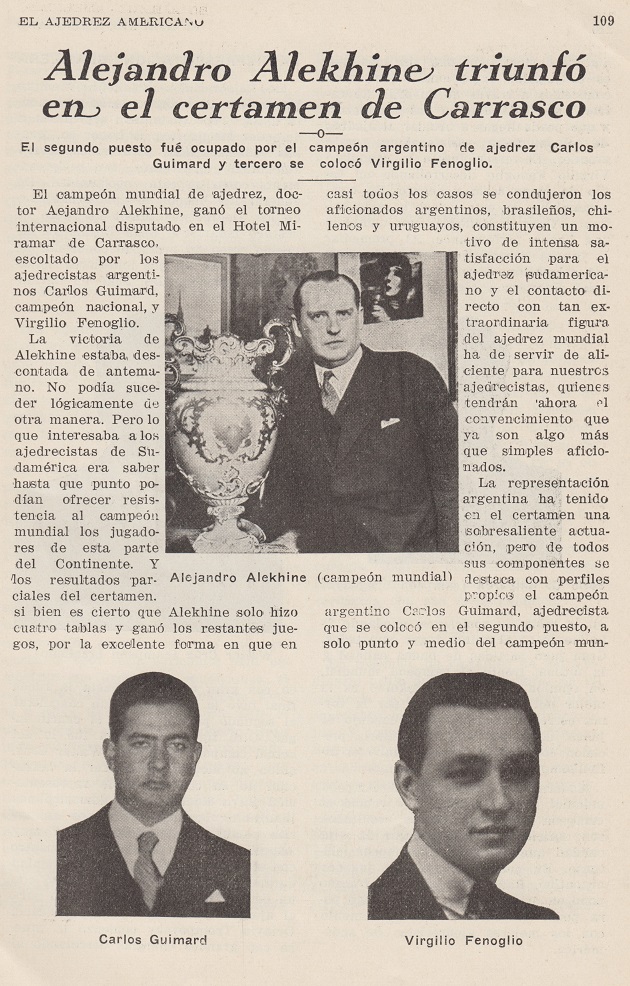

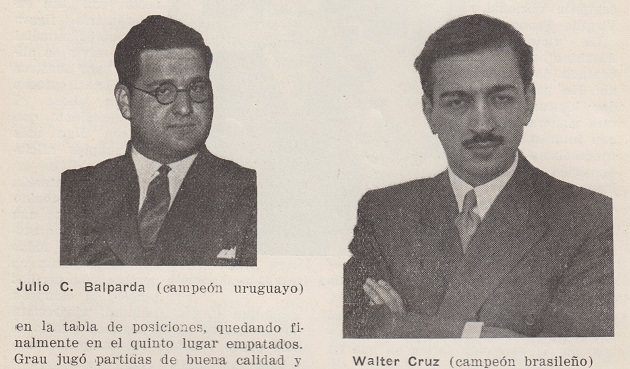

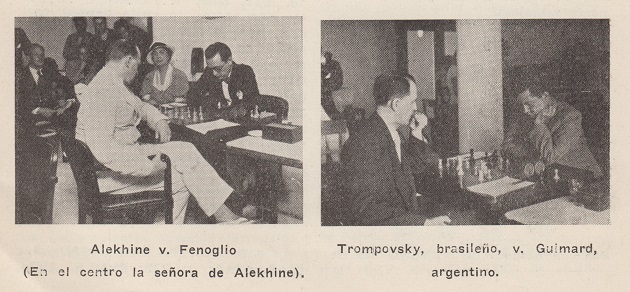

A group photograph was shown in C.N. 4000, from page 113 of El Ajedrez Americano, April 1938, and from the same issue (pages 109, 110 and 113 respectively) further pictures are added:

Another group photograph is on page 64 of Roberto Grau, el maestro by G.C. Grau, J.R. Delfino and J. Morgado (Buenos Aires, 2007).

From the chessgames.com page on Balparda:

However, from page 82 of Ajedrez uruguayo (1880-1980) by Héctor Silva Nazzari (Montevideo, 2013):

‘La carrera ajedrecística de Balparda fue corta como lo fue su vida al fallecer prematuramente el 8 de julio de 1942 a los 39 años de edad.’

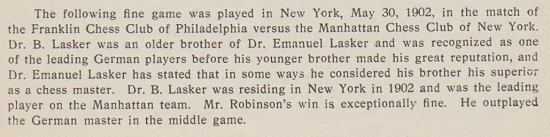

9917. The Lasker brothers

From the Israel National Library link in C.N. 9914 Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) has found a photograph of Emanuel and Berthold Lasker.

With regard to Berthold Lasker, the game below is taken from pages 141-142 of the July-August 1921 American Chess Bulletin:

1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 g3 g6 4 Bg2 Bg7 5 d3 d6 6 Nge2 Nf6 7 O-O O-O 8 f4 e6 9 h3 Ne8 10 Be3 Nd4 11 Kh2 Bd7 12 Rb1 Bc6 13 Qd2 Rc8 14 Nc1 a6 15 Nd1 Nb5 16 c3 f5 17 Nf2 Qc7 18 Ne2 Qf7 19 Ng1 b6 20 Nf3 h6 21 Qc2 Qb7 22 Nh4 Kh7 23 Rbe1 d5 24 Bc1 c4 25 exd5 Bxd5 26 Rxe6 Bxg2 27 Nxg2 cxd3 28 Qxd3 Nf6

29 Rfe1 Rcd8 30 Qe3 Nd6 31 Re7 Qc6 32 Qe6 Rde8 33 Nd3 Rxe7 34 Qxe7 Re8 35 Qa7 Ra8 36 Qe7 Re8 37 Nb4 Qc5 38 Qa7 Rxe1 39 Nxe1 Qf2+ 40 Ng2 Nde4 41 Be3 Qxg3+ 42 Kg1 Qxh3 43 Bd4 Ng3 44 Bxf6 Qh1+ 45 Kf2 Ne4+ 46 Ke3 Qg1+ 47 Kd3 Qd1+ 48 White resigns.

9918. Barcelona archives

Another website with high-quality chess photographs (including Capablanca and Alekhine) is provided by the Arxiu Municipal de Barcelona.

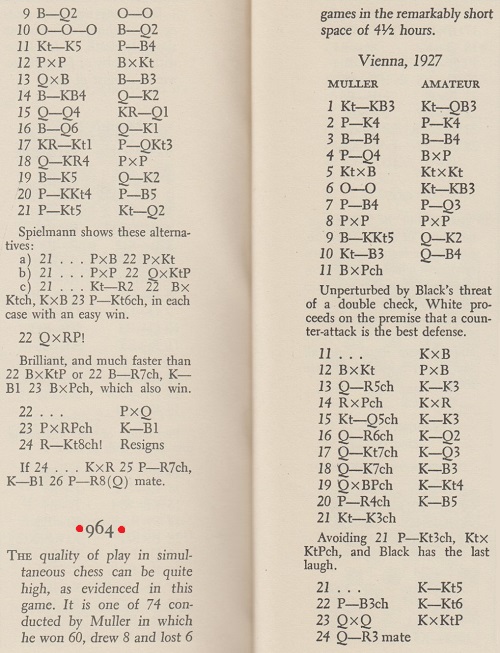

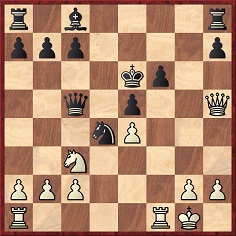

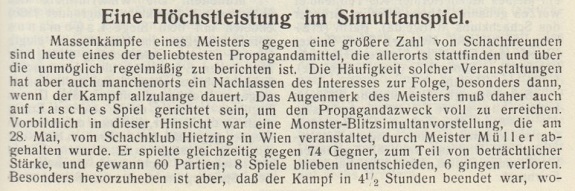

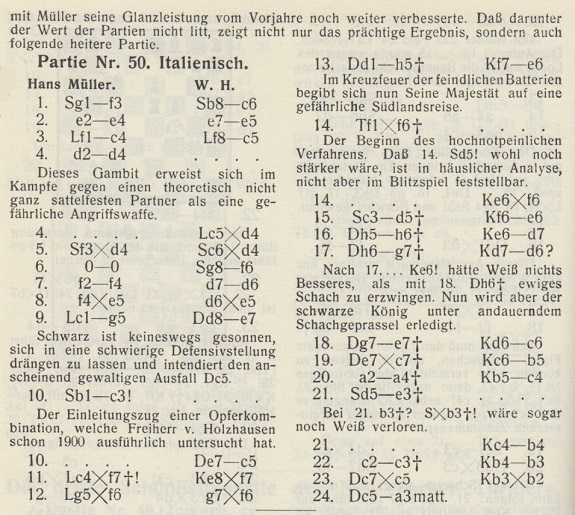

9919. Müller v W.H.

From pages 530-531 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1955):

1 Nf3 Nc6 2 e4 e5 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 d4 Bxd4 5 Nxd4 Nxd4 6 O-O Nf6 7 f4 d6 8 fxe5 dxe5 9 Bg5 Qe7 10 Nc3 Qc5 11 Bxf7+ Kxf7 12 Bxf6 gxf6 13 Qh5+ Ke6

14 Rxf6+ Kxf6 15 Nd5+ Ke6 16 Qh6+ Kd7 17 Qg7+ Kd6 18 Qe7+ Kc6 19 Qxc7+ Kb5 20 a4+ Kc4 21 Ne3+ Kb4 22 c3+ Kb3 23 Qxc5 Kxb2 24 Qa3 mate.

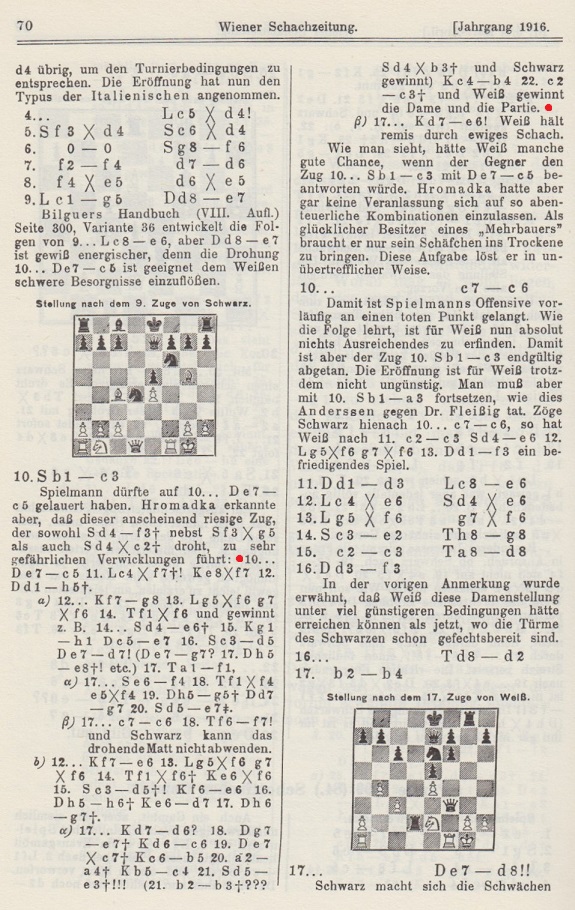

The game was published on pages 163-164 of the June 1927 Wiener Schachzeitung:

On page 276 of the September 1927 issue a correspondent, Franz Schier of Vienna, pointed out that the game had been given as analysis in the March-April 1916 Wiener Schachzeitung in Spielmann v Hromádka, Baden bei Wien, 1914 (annotated in detail on pages 69-72). The relevant page:

The same text is on page 167 of Das Internationale Gambitturnier in Baden bei Wien 1914 by Georg Marco (Vienna, 1916).

9920. Hanging pawns (C.N.s 5725, 5731, 5740 & 6559)

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) notes an earlier occurrence of the term ‘hanging pawns’, including a reference to Steinitz, on page 143 of the July-August 1902 Wiener Schachzeitung, in a note to 20...fxe5 in Gunsberg v Tarrasch, Monte Carlo, 8 February 1902:

‘Daher wohl der Ausdruck “hängende Bauern”, mit welchen Steinitz die Schwäche derartiger Bauernstellungen unübertrefflich scharf angedeutet hat.’

9921. Further photographs from the Israel National Library (C.N.s 9914 & 9917)

Links are added here to a portrait of Tarrasch and another shot of Berthold Lasker. The latter has the same background as in a picture of Emanuel Lasker held by the Library (and also shown in C.N. 8643).

9922. John Lewis Partnership Gazette (C.N. 9772)

Information about the John Lewis Partnership Gazette remains elusive, but Roger Mylward (Lower Heswall, England) points out that some chess-related material is on the John Lewis Partnership website.

9923. Blindfold exhibitions by Louis Paulsen

Patsy A. D’Eramo (North East, MD, USA) has sent us extensive information about Louis Paulsen’s blindfold displays in Pittsburgh in December 1858. Two games are given below, from an exhibition (+6 –4 =0) reported on page 3 of the Pittsburgh Daily Post, 23 December 1858:

Louis Paulsen (blindfold) – Harry Woods

Pittsburgh, 22 December 1858

King’s Gambit Declined

1 e4 e5 2 f4 Bc5 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 fxe5 Nxe4 5 Bxf7+ Kf8 6 Bd5 Qh4+ 7 g3 Bf2+ 8 Kf1 Bxg3 9 Qf3+ Qf4 10 Bxe4 Qxf3+ 11 Nxf3 Bf4 12 Nc3 c6 13 d4 Bxc1 14 Rxc1 Ke7 15 Kg2 Na6 16 Rhf1 d6 17 exd6+ Kxd6 18 Bd3 Be6 19 Rce1 Nb4 20 Ne4+ Kc7 21 Nc5 Bd5 22 Re7+ Kb6 23 Rxb7+ Ka5

24 a3 Bxf3+ 25 Rxf3 Resigns.

Source: Pittsburgh Gazette, 24 December 1858, page 3.

Louis Paulsen (blindfold) – C. Von Bonnhorst

Pittsburgh, 22 December 1858

Irregular Opening

1 e4 d6 2 d4 c6 3 Nf3 Bg4 4 Nc3 e6 5 Be2 Be7 6 O-O Bxf3 7 Bxf3 Nf6 8 b3 Nbd7 9 Bb2 e5 10 Ne2 O-O 11 c4 b6 12 Qc2 c5 13 d5 Kh8 14 Ng3 Ng8 15 Be2 Nh6 16 f4 a5 17 fxe5 Nxe5 18 Rad1 f6 19 Nh5 Qe8 20 Nf4 Rc8 21 Ne6 Rg8 22 Qc3 Nd7 23 Qh3 Nf8 24 Bh5 Nf7 25 Rf4 Nxe6 26 dxe6 Ng5 27 Qh4 Qf8 28 Rdf1 Nxe6

29 Bg6 Ng5 30 Rf5 h6 31 Rxg5 Bd8 32 Rgf5 Rc7

33 Rxf6 gxf6 34 Rxf6 Bxf6 35 Bxf6+ Rgg7 36 Qxh6+ Kg8 37 Bf5 Rxg2+ 38 Kxg2 Qxh6 39 White resigns.

Source: Pittsburgh Gazette, 24 December 1858, page 3.

9924. Alekhine’s vase

Concerning the photograph of Alekhine in C.N. 9916, from page 109 of El Ajedrez Americano, April 1938, Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) mentions that in a BBC radio interview in 1938 Alekhine described the vase as ‘the only thing I was allowed to bring out of Russia in 1921 when I left’.

The full audio file and transcript are easily found on the Internet. As mentioned in a ChessBase article dated 14 June 2010, we believe that both were first made available online in 2003, by Hanon Russell at the Chess Café.

Regarding the vase, see too C.N. 3697.

9925. Buenos Aires, 1931

From opposite page 8 of Estrategia, 1 March 1942:

9926. The Belgian Times

A paragraph is quoted with all due caution from page 163 of the July 1875 City of London Chess Magazine:

‘It appears that the Belgian Times, a newspaper circulating in Brussels and London, has for some time past had a chess column. This part of the journal has now been given into the charge of Dr Zukertort, and it is not in any way necessary for us to say that it could not be in better hands.’

9927. EG

The January 1968 issue of EG referred to in C.N. 9897 in connection with Metger v Paulsen, Nuremberg, 1888 is available online. An observation by the Editor, John Roycroft, on page 301:

‘It is, to us, quite astonishing how frequently the famous classical positions are subject to distortion, mis-quotation and confused history.’

9928. Purdy on Barden

A comment by C.J.S. Purdy about A Guide to Chess Openings by Leonard Barden (London, 1957), on page 104 of the April 1957 Chess World:

‘... it’s the best book on openings ever.’

9929. Trouble over gambits and sacrifices

A common example of the plumping process discussed in C.N. 9887 concerns quotations. When plumpers say what a given master ‘once said’, ‘often said’ or ‘used to say’, they are simply opting for one version of what earlier plumpers said was said. No caveats are expressed, and random possibilities are presented as fact.

A dictum usually ascribed to Steinitz is that the best way to refute an offer is to accept it. The wording varies, au gré du preneur, and either ‘gambit’ or ‘sacrifice’ may be plumped for.

The investigator hoping that a McFarland book will resolve the question may turn to William Steinitz, Chess Champion by Kurt Landsberger (Jefferson, 1993), but it fell far short of that publisher’s usual standards. Page 282 attributed this remark to Steinitz:

‘“The refutation of a sacrifice fervently consists in its acceptance” (80).’

The word ‘fervently’ is peculiar, but the matter can be pursued because the ‘(80)’ relates to a source note on page 473. Any hope of a precise reference to, perhaps, one of Steinitz’s books or columns, or to the International Chess Magazine, is dashed. Note 80 merely states:

‘80. Levy & Reuben. The Chess Scene. London: Faber & Faber, 1974.’

So the next step, however unpromising, is to turn to The Chess Scene, which has the following on page 70:

‘The refutation of a sacrifice frequently consists in its acceptance. Steinitz.’

As feared, we are no further forward, except that ‘fervently’ can be seen as Landsberger’s mistranscription of ‘frequently’.

Although they did not bother to say so, the exact wording given by Levy and Reuben was in the entry for Epigrams on page 119 of The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks (London, 1970):

‘The refutation of a sacrifice frequently consists in its acceptance. W Steinitz.’

Again, no source was supplied.

A few years earlier, the ‘gambit’ version had cropped up twice in book two of The Middle Game by Max Euwe and Haije Kramer (London, 1965):

‘Steinitz would certainly have taken it [a pawn], following his own motto “The only way to refute a gambit is to accept it”.’ (Page 276).

‘“The only way to refute a gambit”, said Steinitz, “is to accept it”.’ (Page 329).

Books co-authored by Savielly Tartakower and Julius du Mont had both the ‘sacrifice’ and the ‘gambit’ versions, with Steinitz mentioned in connection with the former:

‘Steinitz’s dictum that “a sacrifice is best refuted by its acceptance” is here put to the test.’

Source: page 233 of 500 Master Games of Chess, book one (London, 1952).

‘On the principle that the best refutation of a gambit is to accept it.’

Source: page 16 of 100 Master Games of Modern Chess (London, 1954).

From the previous decade, page 178 of The World’s a Chessboard by Reuben Fine (Philadelphia, 1948) had this:

‘Steinitz used to say that the way to refute a gambit is to accept it.’

Fine’s text had originally appeared on page 24 of the Chess Review, June-July 1946. On page 43 of the November 1946 issue I.A. Horowitz wrote after 1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4:

‘As a rule, and this is no exception, the best way to meet a gambit is to accept it ...’

Larry Evans’ books and articles often referred to the remark sourcelessly, and page 86 of The Italian Gambit by Jude Acers and George S. Laven (Victoria, 2003) even attributed it to him, also sourcelessly:

‘The best way to refute a gambit is to accept it. – GM L. Evans.’

From pages 221-222 of The Human Side of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1952), in his notes to an 1860 game won by Anderssen with the Evans Gambit:

‘To decline a gambit in those days was almost as unthinkable as for a gentleman to decline to fight a duel. Offering the gambit was a challenge that one could refuse only at the risk of stamping himself as a sissy and a coward.

Later on Steinitz, with the attitude of “a pawn’s a pawn for a’ that”, gave the quietus to aristocratic chess.’

That brings to mind a paragraph on page 4 of Winning with Chess Psychology by Pal Benko and Burt Hochberg (New York, 1991):

‘Steinitz believed that the choice of a plan or move must be based not on a single-minded desire for checkmate but on the objective characteristics of the position. One was not being a sissy to decline a sacrifice, he declared, if concrete analysis showed that accepting it would be dangerous. There was no shame in taking the trouble to win a pawn. A superior endgame was no less legitimate a goal of an opening or middlegame plan than was the possibility of a mating attack.’

The penultimate sentence will take us on to a related remark regularly ascribed to Steinitz. One example comes from page 228 of The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played by Irving Chernev (New York, 1965):

‘... as Steinitz once mentioned, “A pawn ahead is worth a little trouble”.’

The observation ‘When in doubt, take a pawn. A pawn is worth a little trouble’ is on page 282 of Landsberger’s above-mentioned book on Steinitz. Again, the reference is ‘(80)’, and again the quote is on page 70 of Levy and Reuben’s The Chess Scene, again without a source.

And so it goes on. Many chess writers do not take even a

little trouble and, above all, they pretend to possess

knowledge which they do not have. Entire websites are

‘devoted’ to sourceless quotations, that most facile way

of filling space, and they are a plumper’s charter.

Assistance from readers in tracking down the exact origins of the gambit and sacrifice remarks will be greatly appreciated.

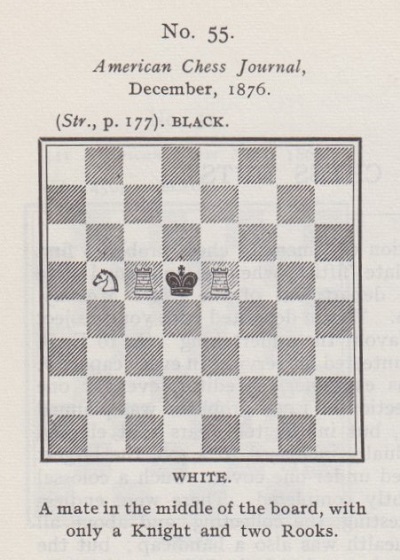

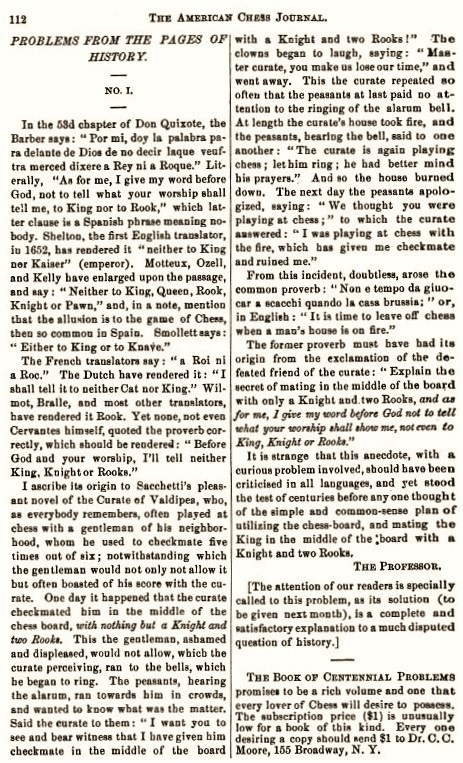

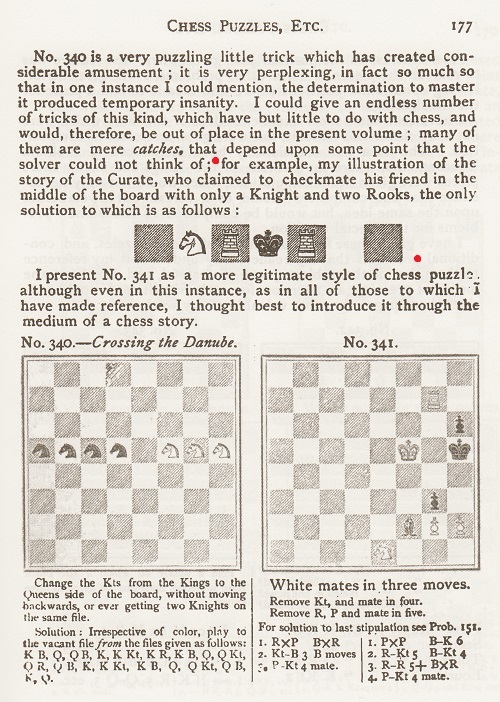

9930. Two rooks and a knight

‘I wonder whether it is a very old story – that puzzle by (I believe) J.H. Blackburne. Place the black K on one of the four central squares, and then take from the box two white rooks and one white knight. Now arrange these three white pieces so that the black K stands mated. No moves are to be made – simply place them in such a manner that the condition is fulfilled. As there are no pawns, there is necessarily more than one solution, but the principle is the same in each. If you do it in 15 minutes you will be smarter than I was.’

This problem was set by P.H.

Williams. The source will be given in a future C.N.

item, together with the solution (which, perhaps

understandably, was rather hidden away by Williams).

9931. Dissected chessboard puzzle

An item by P.H. Williams on page 375 of the September 1909 Chess Amateur:

‘How many of you know the dissected chessboard puzzle called “The Weekly Telegraph” puzzle? This is a little three-penny box full of sections of a chessboard, which it is required to fit together in a perfect square, black and white alternately. I took about four hours to do it, and had to have recourse to numbering the fragments, and had to write down my positions in order to evolve a system of exhaustion. It is extremely ingenious, as haphazard experiment is of no avail. I cannot see the faintest clue in the pieces, and I believe there is but one solitary solution. It is diabolically irritating.

“Jig-saw” puzzles are all the rage just now, and this is somewhat on the same lines, though the “picture” to be constructed is a simple chessboard. All the pieces are rectangular, and there are 12 of them, but they have been cut by somebody with atrocious ingenuity. Boiling oil is what I prescribe for this gentleman. I shall never forget the sensation I experienced when I got the last piece in correctly. Several times previously I had got 11 pieces together, and the twelfth fitted nicely, but the colours of the squares were wrong – a maddening disappointment. Buy the thing and send it to your enemy.’

The puzzle can be seen online, in the Jerry Slocum Mechanical Puzzle Collection (Indiana University).

9932. Iberia

From page 245 of the August 1927 Wiener Schachzeitung:

‘Iberia ist der Titel einer neuen spanischen Schachzeitung in vornehmer Ausstattung, zu deren Hauptmitarbeitern R. Réti zählt. Verwaltung: Barcelona, Aribau Nr 179.’

Does the magazine, which ran from May to September 1927, have any material of particular interest, by Réti or other contributors?

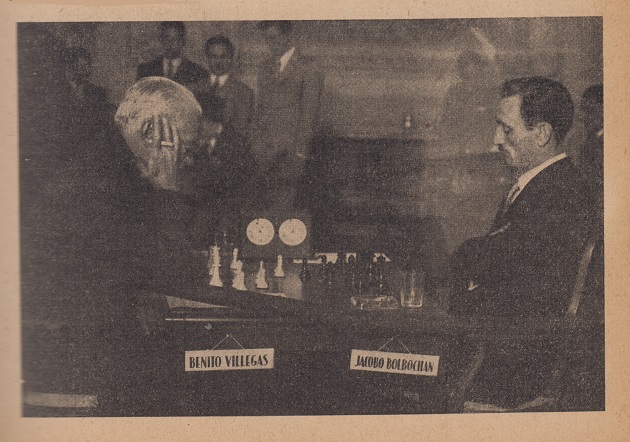

9933. Mar del Plata, 1942

The photographs below are from Estrategia (April 1942, page 39; May 1942, page 71; June 1942, page 103; June 1942, page 108):

9934. Capablanca and Camelot (C.N. 7164)

This photograph of Capablanca playing Camelot against Anne Morgan (first shown in C.N. 3024) comes from the Diario de la Marina (Havana), 10 March 1942:

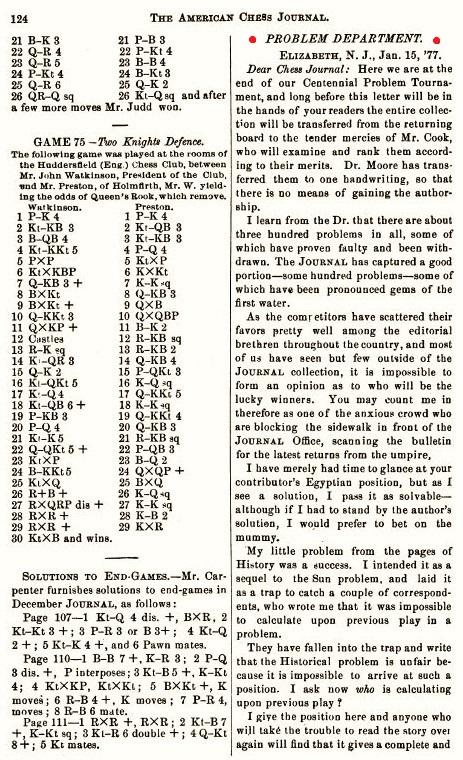

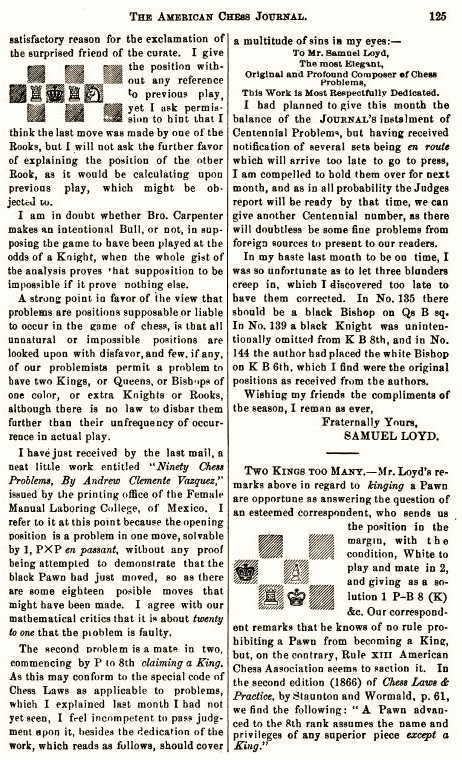

9935. Two rooks and a knight (C.N. 9930)

The problem in C.N. 9930 was given by P.H. Williams under the heading ‘Ingenious Puzzle’ on page 280 of the Chess Amateur, June 1909. In the ‘Answers to Correspondents’ section on page 345 of his August 1909 column he wrote:

‘A. Mendes da Costa: White’s Rs at Q5 and KB5, Kt at KKt5; Black K at K4 – an impossible position, of course, but mate.’

As noted by Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England), the composition is on page 52 of Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems by Alain C. White (Leeds, 1913):

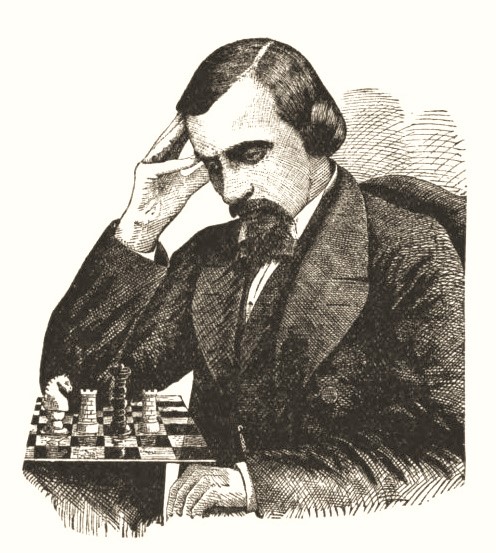

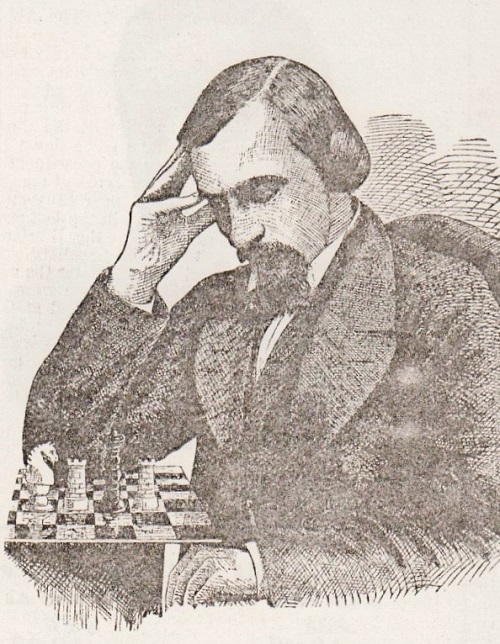

Our correspondent also points out White’s comment about Loyd on page 53:

‘His wood-cuts in the American Chess Journal testify to his skill in this most difficult branch of work. There was often a whimsical characteristic concealed in his engravings. I remember the one of Harrwitz, excellently done; but if one looks closely at the board before him, at which Harrwitz is looking with serious consideration, one finds that Loyd has depicted on it that absurd position shown in No. 55.’

The illustration (based on the photograph in C.N. 6286) was published at the end of the December 1878 edition of the American Chess Journal:

Below is the picture’s earlier appearance, on page 1566 of the Scientific American Supplement, 17 November 1877:

Regarding the book extract above, the date in the reference ‘American Chess Journal, December 1876’ is not, as might be imagined, an error for December 1878. Both issues of the periodical had material on the position.

Page 112 of the December 1876 edition:

The solution was published on pages 124-125 of the January 1877 issue:

Finally, the reference ‘Str., p. 177’ in A.C. White’s book is to Loyd’s volume Chess Strategy (Elizabeth, 1878). The full page:

9936. Iberia (C.N. 9932)

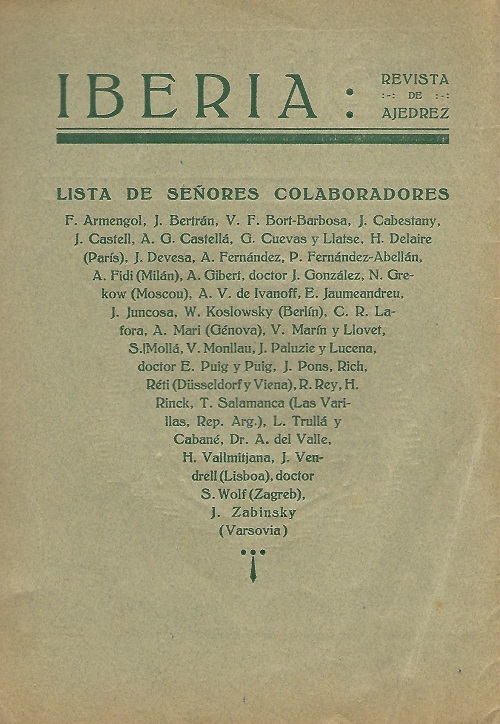

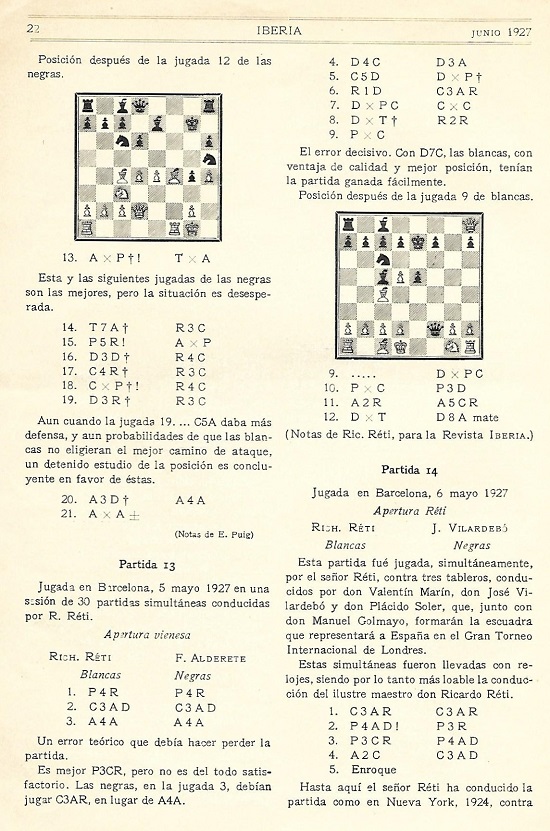

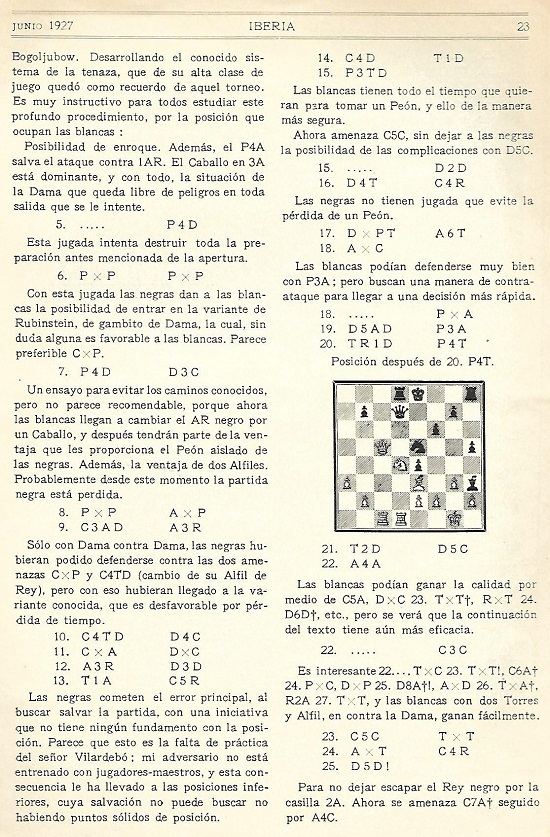

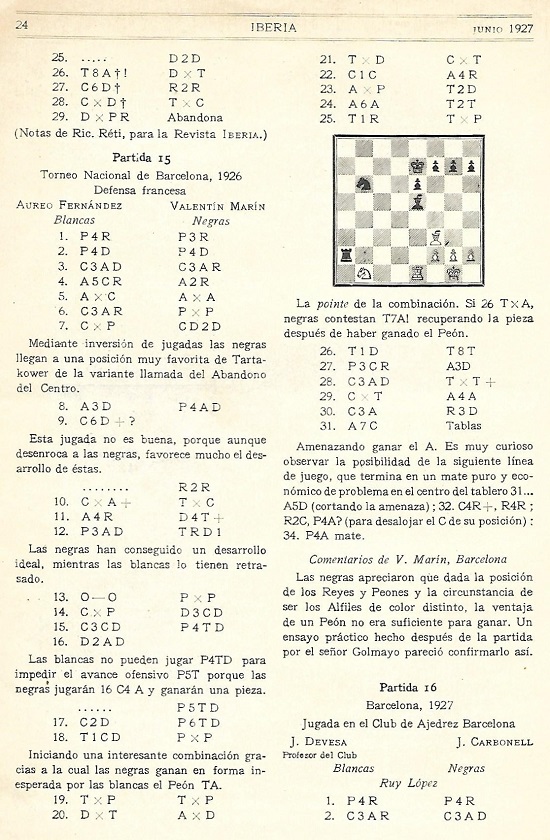

Miquel Artigas (Sabadell, Spain) has forwarded Réti material published in the short-lived Spanish periodical Iberia:

The two Réti games published by Iberia:

Black: F. Alderete: 1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 Qg4 Qf6 5 Nd5 Qxf2+ 6 Kd1 Nf6 7 Qxg7 Nxd5 8 Qxh8+ Ke7 9 exd5 Qxg2 10 dxc6 d6 11 Be2 Bg4 12 Qxa8 Qf1 mate.

Black: J. Vilardebó: 1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 g3 c5 4 Bg2 Nc6 5 O-O d5 6 cxd5 exd5 7 d4 Qb6 8 dxc5 Bxc5 9 Nc3 Be6 10 Na4 Qb5 11 Nxc5 Qxc5 12 Be3 Qd6 13 Rc1 Ne4 14 Nd4 Rd8 15 a3 Qd7 16 Qa4 Ne5 17 Qxa7 Bh3 18 Bxe4 dxe4 19 Qc5 f6 20 Rfd1 h5 21 Rd2 Qg4 22 Bf4 Ng6 23 Nb5 Rxd2 24 Bxd2 Ne5 25 Qd5 Qd7 26 Rc8+ Qxc8 27 Nd6+ Ke7 28 Nxc8+ Rxc8 29 Qxe4 Resigns.

9937. A Capablanca lecture

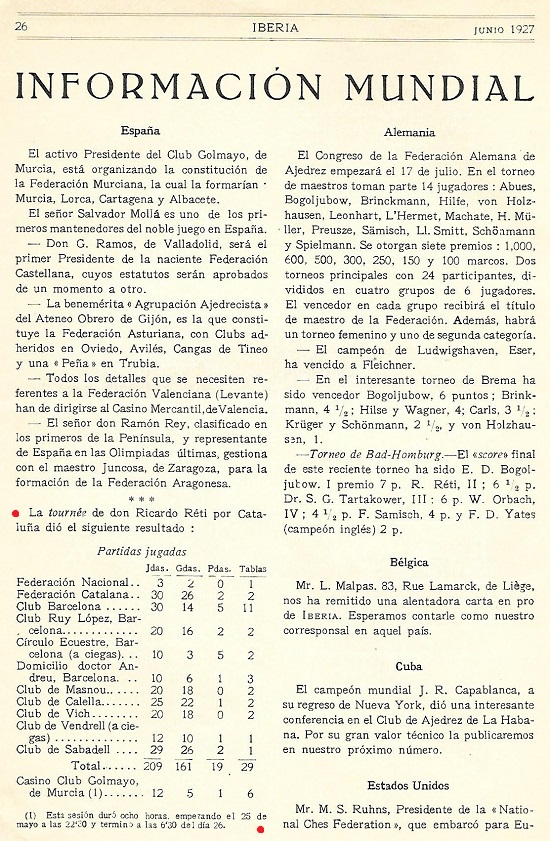

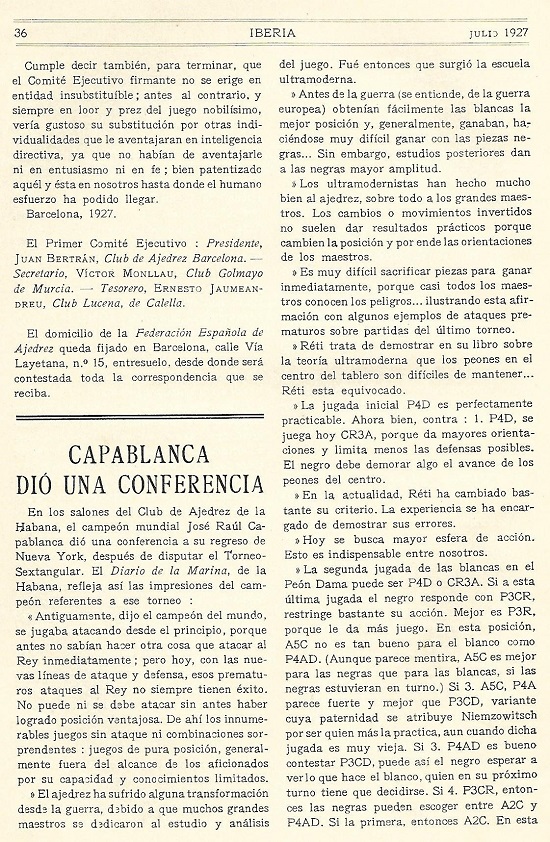

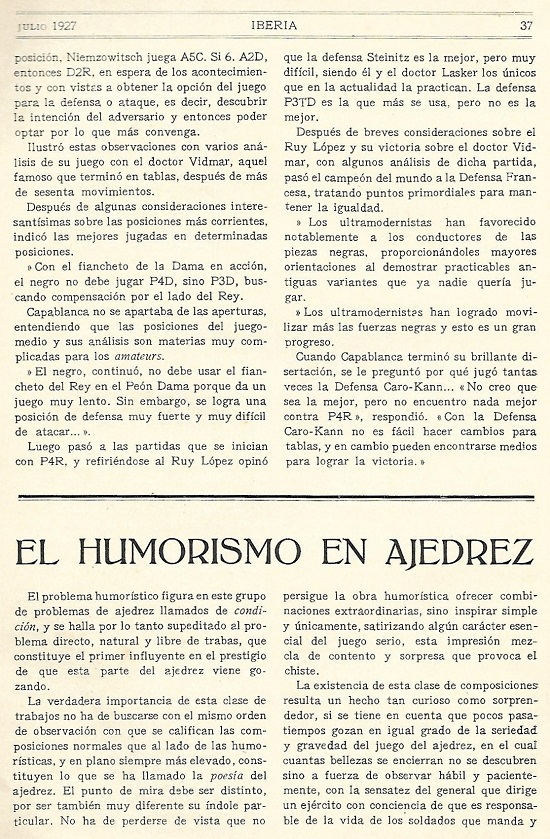

The lecture by Capablanca in Havana referred to on page 26 of Iberia, June 1927 (C.N. 9936) has been provided by Miquel Artigas (Sabadell, Spain):

9938. Voltaire and chess

Some old references:

- ‘Voltaire und das Schach’ by Dr Koerting (Leipzig), Deutsche Schachzeitung, May-June 1883, pages 129-132;

- ‘Les joueurs d’échecs. Voltaire’, by Charles Joliet, La Stratégie, 15 July 1899, pages 225-226;

- ‘Voltaire and Chess’ by ‘Cluen’, BCM, April 1902, pages 156-158;

- ‘Voltaire og skáktaflið’, Í Uppnámi, 4/1902, pages 61-63;

- ‘Voltaire joueur d’échecs’, Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français, issue 9 (1927), pages 257-259.

The articles in the German, British and Icelandic publications were similar, and the BCM had this introductory note to its translation:

‘The following article is from an old volume of the Leipzig Illustrirte Zeitung. It has been recently republished by the chess editor of Die Bohemia ...’

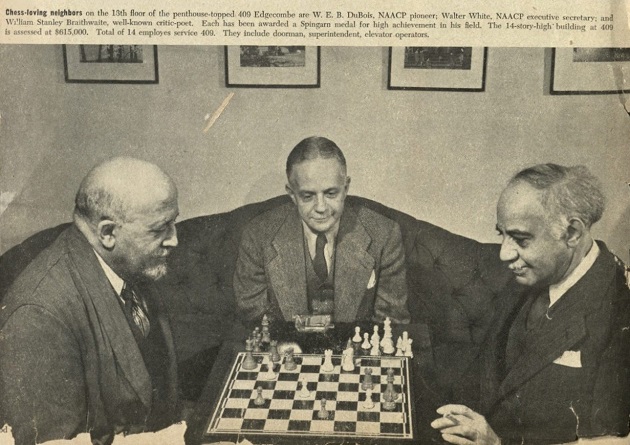

9939. DuBois, White and Braithwaite

Stephen L. Carter (New Haven, CT, USA) sends a photograph from Ebony, November 1946 in connection with the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). A staged chess position is being studied by W.E.B. DuBois, Walter Francis White and William Stanley Braithwaite:

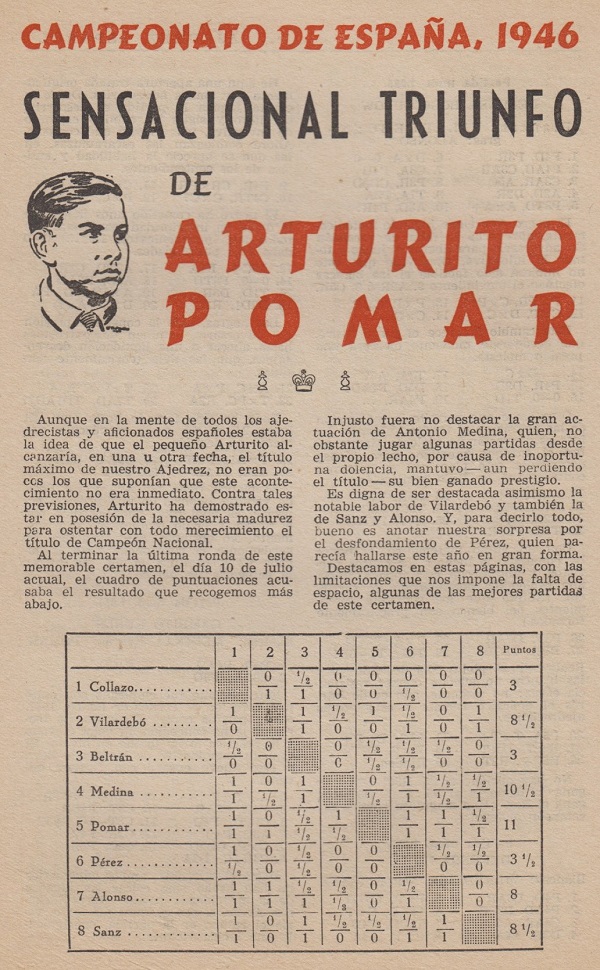

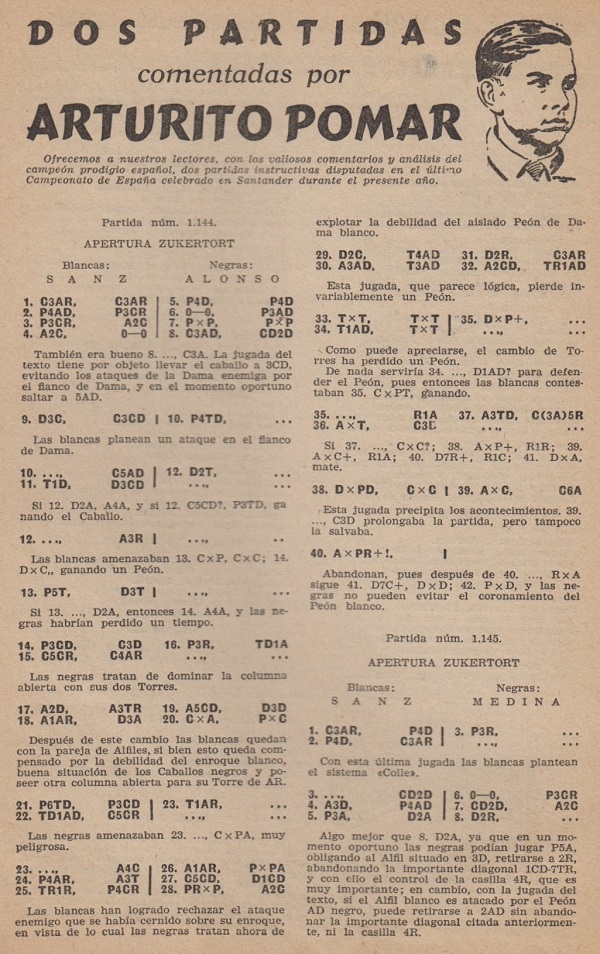

9940. Arturo Pomar

London 1946 Book of the “Sunday Chronicle” Chess Tournament (Sutton Coldfield, 1946), page 39

At the age of 14 Arturo Pomar won the 1946 Spanish championship in Santander, as reported on pages 209 and 213 of Ajedrez Español, July 1946:

On pages 378-379 of the December 1946 issue Pomar annotated two games from the championship:

Sanz v Alonso: 1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 g3 Bg7 4 Bg2 O-O 5 d4 d5 6 O-O c6 7 cxd5 cxd5 8 Nc3 Nbd7 9 Qb3 Nb6 10 a4 Nc4 11 Rd1 Qb6 12 Qa2 Be6 13 a5 Qa6 14 b3 Nd6 15 Ng5 Nf5 16 e3 Rac8 17 Bd2 Bh6 18 Bf1 Qc6 19 Bb5 Qd6 20 Nxe6 fxe6 21 a6 b6 22 Rac1 Ng4 23 Rf1 Bg5 24 f4 Bh6 25 Rfe1 g5 26 Bf1 gxf4 27 Nb5 Qb8 28 exf4 Bg7 29 Qb2 Rc5 30 Bc3 Rc6 31 Qe2 Nf6 32 Bb2 Rfc8 33 Rxc6 Rxc6 34 Rc1 Rxc1 35 Qxe6+ Kf8 36 Bxc1 Nd6 37 Ba3 Nfe4 38 Qxd5 Nxb5 39 Bxb5 Nc3 40 Bxe7+ Resigns.

Sanz v Medina: 1 Nf3 d5 2 d4 Nf6 3 e3 Nbd7 4 Bd3 c5 5 c3 Qc7 6 O-O g6 7 Nbd2 Bg7 8 Qe2 O-O 9 c4 b6 10 e4 dxe4 11 Nxe4 cxd4 12 Nxd4 Bb7 13 Nb5 Qc6 14 f3 a6 15 Nbc3 Ne5 16 Nxf6+ Qxf6 17 Be4 Bxe4 18 Qxe4 Qd6 19 Be3 e6 20 Na4 f5 21 Qc2 Rab8 22 Rad1 Qc6 23 Rc1 Rfc8 24 Rf2 Rd8 25 Rd2 Rxd2 26 Bxd2 Rc8 27 Be3 Nd7 28 Qb3 Rb8 29 Kh1 Bf8 30 Nc3 Rc8 31 Qa4 Qxa4 32 Nxa4 Rc6 33 b3 Nc5 34 Nxc5 Bxc5 35 Bxc5 Rxc5 36 Re1 Kf7 37 f4 b5 38 Re5 Rxe5 39 fxe5 bxc4 40 bxc4 Ke7 41 Kg1 Kd7 42 Kf2 Kc6 43 Ke3 Kc5 44 Kd3 g5 45 g3 h6 46 h3 a5 47 Kc3 a4 48 Kd3 a3 49 Kc3 f4 50 gxf4 gxf4 51 Kd3 f3 52 Ke3 Kxc4 53 Kxf3 Kd4 54 Kf4 Kd5 55 h4 Kd4 56 Kg4 Kxe5 57 Kh5 Kf5 58 Kxh6 e5 59 h5 e4 60 Kg7 e3 61 h6 e2 62 h7 e1(Q) 63 h8(Q) Qe5+ 64 Kg8 Qxh8+ 65 Kxh8 Ke4 66 White resigns.

9941. Hanging pawns

Assertions in The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977) and The Batsford Chess Encyclopedia by Nathan Divinsky (London, 1990):

- Golombek (entry on hanging pawns by Wolfgang Heidenfeld, page 135): ‘The term hanging pawns stems from Steinitz.’

Divinsky (entry on hanging pawns, page 81): ‘Steinitz used this term ...’

- Golombek (entry on Nimzowitsch by Raymond Keene, page 213): ‘Nimzowitsch introduced into chess terminology such phrases as ... “hanging pawns” ...’

Divinsky (entry on Nimzowitsch, page 144): ‘Nimzowitsch introduced into chess terminology such phrases as ... “hanging pawns” ...’

The discrepancy in the Golombek book was pointed out by

W.H. Cozens on page 400 of the September 1978 BCM

but remained in the 1981 paperback edition (page 199 and

page 308).

From page 98 of Pocket Book of Chess by Raymond Keene (London, 1988):

‘The term “hanging pawns” was coined by Wilhelm Steinitz, who was world champion from 1886 to 1894.’

In short, plenty of claims, contradictions and copying, but no corroboration.

Our latest feature article, Hanging Pawns in Chess, brings together the C.N. items which have tried to establish when the term first appeared in print. So far, the earliest known instance (shown by Thomas Niessen in C.N. 9920) is dated 1902, i.e. post-Steinitz and pre-Nimzowitsch.

9942. Potter’s retirement

Following the death of W.N. Potter, a strong player and an exceptional writer, the BCM published an obituary which was two-thirds of a page long (April 1895 issue, page 180). The remaining third of that page and the next three pages were given over to the death of G.C. Heywood.

Page 226 of the Chess Monthly, April 1895 included the following in its notice on Potter:

‘Some ten years ago he retired from chess and chess circles altogether, living in perfect seclusion at Sutton, where he died regretted but not forgotten by his numerous friends and admirers of his sterling qualities.’

What is known about why Potter retired from the game, as a player and a writer?

9943. Sea-warfare chess/minefield chess

From page 144 of CHESS, June 1942:

The variant had been mentioned, with a very similar wording, by J.A. Pietzcker of Victoria on page 269 of the Australasian Chess Review, 8 October 1936:

‘The great international chess congress lured me to Nottingham. I arrived there on an “off” day, on which the masters were being fêted at a garden party. But it was wet and cold, and before dinner nearly all the leading players were in the lounge of their hotel in frivolous mood.

With true Australian effrontery, I was soon on speaking terms, mainly through introductions by Mr Winter, the British champion. It was a memorable evening. For the moment, the strong silent men of the tourney were weak, loquacious mortals – all of them friendly – chaffing each other, and playing games. Chess boards were in evidence. Some were playing a “freak” game.

Each player wrote two squares in a sealed envelope. The squares, which had to be on the player’s own side of the board, were mined. If the opponent planted a piece on a mined square, it could be blown up. A king, on touching such a square, was immediately destroyed, and the game was over.

The game appeared to be not to disclose the mined squares until the king crossed into the enemy’s territory. Pieces were rapidly exchanged, and the fun began when kings were supporting pawns on the road to queening.

Dr Lasker, Capablanca and Bogoljubow preferred contract bridge, and appeared to be far more adventurous in their bidding than in their bridge play. I saw Lasker go down five tricks on a three-no-trump call that would have horrified C.G. Watson.’

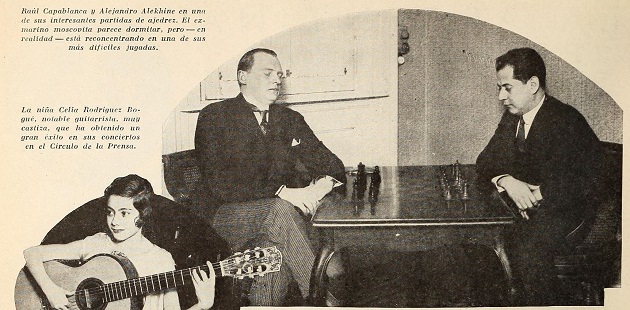

9944. Pictures of Capablanca and Alekhine, Buenos Aires, 1927 (C.N. 4814)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) writes:

‘The picture of Capablanca in C.N. 4814 which was on page 3 of the October 1927 issue of El Ajedrez Americano is part of a rather strange photograph of both Capablanca and Alekhine which has been published in several places. A poor-quality version is on page 330 of Miguel A. Sánchez’s José Raúl Capablanca. A Chess Biography (Jefferson, 2015) with a caption stating that it was published in the 16 September 1927 edition of Crítica and that “though it is a poor image, and probably retouched, it is of extraordinary historical value”.

I have found a better copy on page 38 of the January 1928 issue of Cine-Mundial:’

9945. Caissa

Depictions of the goddess Caissa are easily found, but we welcome rare or unusual specimens. From page 383 of Ajedrez Español, December 1946:

9946. A clear win

‘A chessplayer should recognize a clear win, as a reader recognizes a long word without spelling it.’

Source: page 11 of Chess Endings by Edward Freeborough (London, 1891).

9947. The hedgehog formation (C.N.s 7574 & 8211)

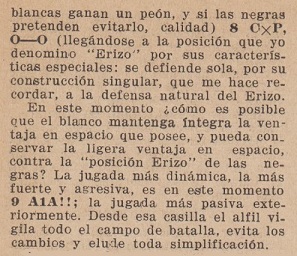

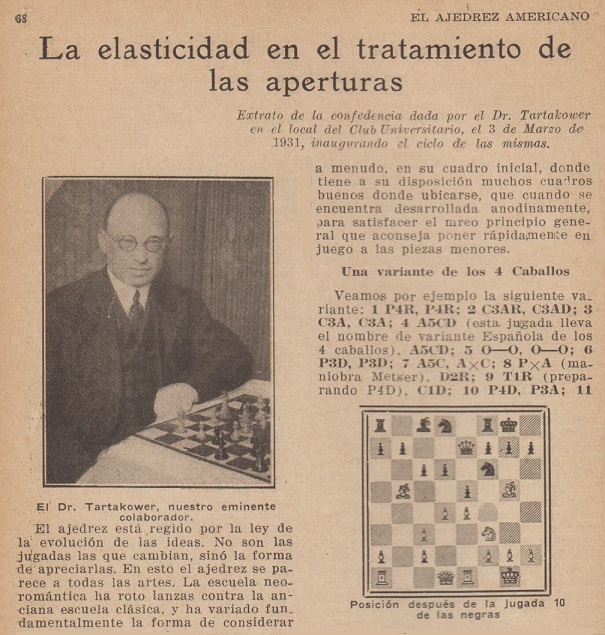

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) points out hedgehog references on page 69 of El Ajedrez Americano, March 1931, concerning the line 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 d6 4 d4 Bd7 5 Nc3 Nf6 6 O-O Be7 7 Re1 exd4 8 Nxd4 O-O:

The text was in an extract from a lecture on openings which Tartakower gave in Buenos Aires on 3 March 1931, as specified by the magazine in its heading on the previous page:

9948. Spassky v Fischer match cartoons

An Icelandic webpage presents a set of 19 cartoons on the 1972 world championship match.

9949. Reshevsky in 1930

From page 46 of the Exhibitors Herald World, 8 February 1930:

9950. Chess Secrets

C.N. 3779 (see too Reviewing Chess Books) quoted a remark by Fred Reinfeld on page 96 of Chess Review, March 1951:

‘If a reviewer spends all of an hour nowadays reading the book he is supposed to be reviewing, he feels that he has done more than his duty. This is particularly unfortunate in the field of chess, in which it often requires years to write a good book.’

That was the first paragraph of his highly favourable review of Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters by Edward Lasker (New York, 1951). The second paragraph:

‘Chess Secrets must have taken many years to write, and the events which it chronicles took some 40-odd years to live through. I consider myself fortunate to have had the opportunity of reading this book three times: in manuscript, in galley proofs and in page proofs. Each reading was an enjoyable experience.’

Reinfeld’s three readings did not save the book from its many historical errors, some of which have been mentioned in C.N., but the qualities of Chess Secrets are not in dispute.

On page 40 of Chess World, February 1952, C.J.S. Purdy wrote:

‘This excellent book is by the international master Edward Lasker, but the best of the many good things in it are by Emanuel Lasker. We mean things Emanuel, in his lifetime, said to Edward and from which Edward profited in his own games, and put in this book. The two were unrelated but great friends.

Edward Lasker is one of the few chess writers who have the faculty of writing well and entertainingly; he lapses but rarely into journalism.

... Some people like their expositions of chess to be systematic. That is important in mathematics or science but much less so in chess, which is more art than science. This book, with its sugar-coating of gossip, will teach most students more than many orthodox text-books. Drudgery should be avoided.

... The reviewer can claim to have derived more entertainment from Chess Secrets than any other chess book, and in our view there is not much to beat it for instruction, either.’

On page 133 of the September-October 1967 Chess World Purdy referred back to his review and added:

‘People picking it up casually would mistake it for a book of gossip about the masters, which it partly is. They overlook that it contains 75 superbly annotated games by one of the best chess writers and annotators of all time. Each one is a work of art.’

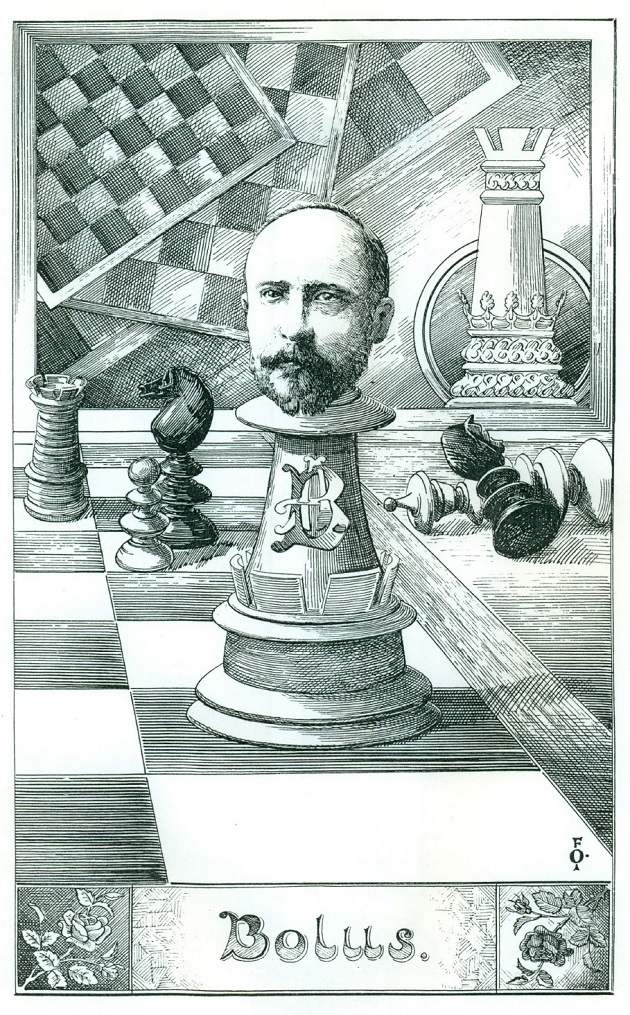

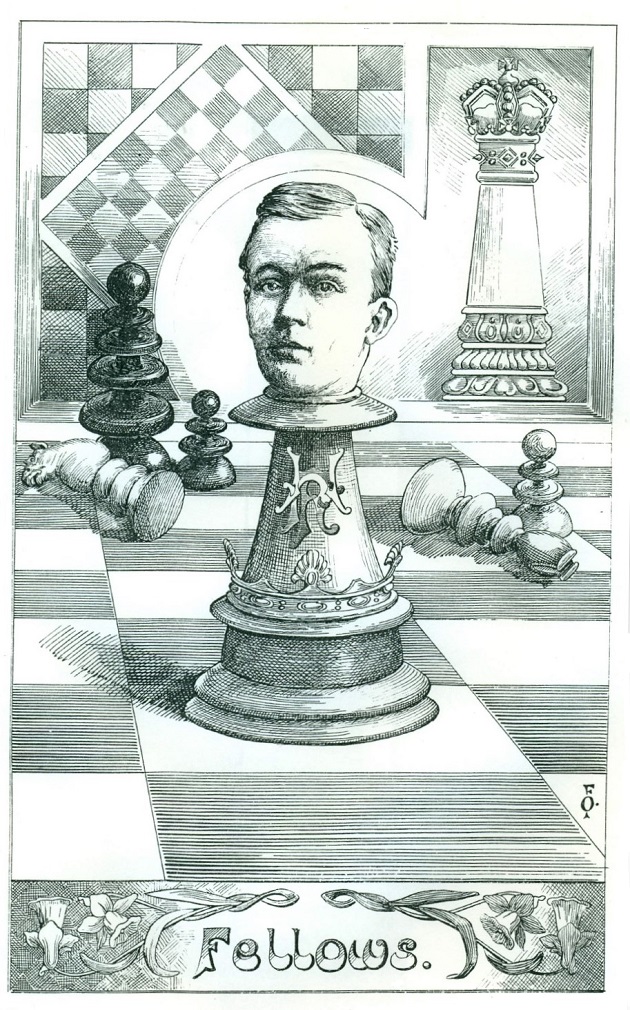

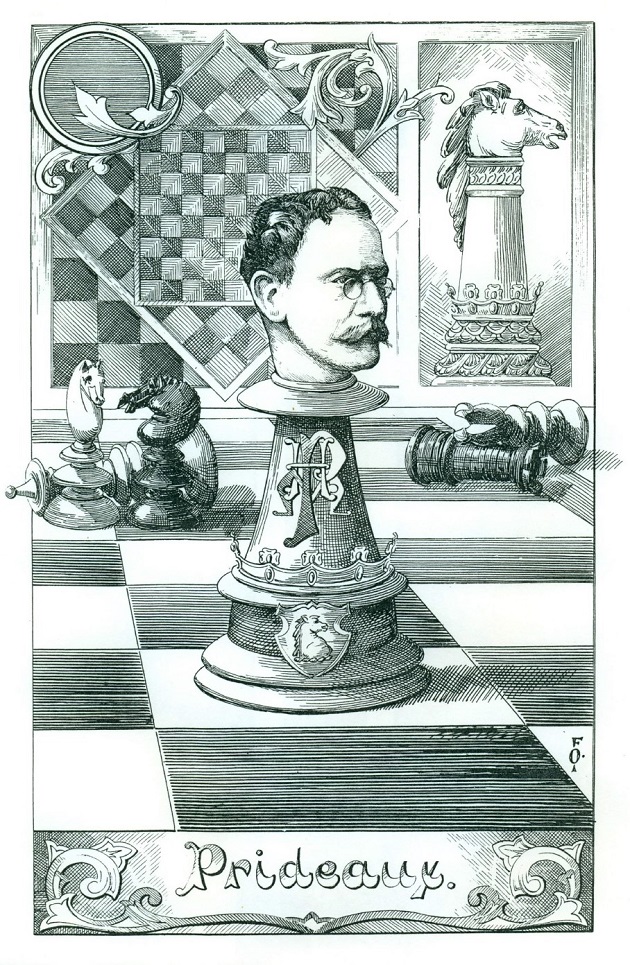

9951. Frederick Orrett

Three further portraits by Frederick Orrett (see C.N.s 9722, 9725, 9751, 9811 and 9872) are shown, courtesy of Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

Andrew Bolus

Arthur G. Fellows

Henry Maxwell Prideaux

| First column | << previous | Archives [142] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.