Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [143] | next >> | Current column |

9952. The best way to refute a gambit (C.N. 9929)

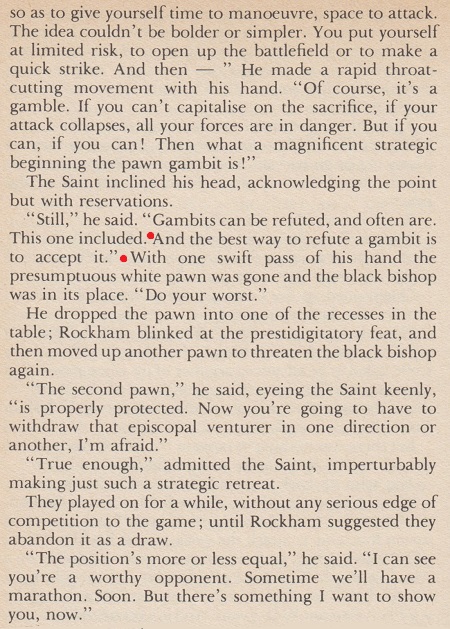

‘And the best way to refute a gambit is to accept it.’

That observation occurs in The Pawn Gambit on page 158 of Send for the Saint by Leslie Charteris (London, 1977):

In a description of an Evans Gambit game the previous page had references to ‘the Göttingen manuscript of 1490’, ‘Bird, Blackman, Staunton, Anderssen’ and ‘Morphy, Steinity’.

The Pawn Gambit (the title The Pawn Gamble can also be found) was not written by Charteris. The contents page of Send for the Saint specified ‘Original Teleplay by Donald James’ and ‘Adapted by Peter Bloxsom’. The corresponding television episode, starring Roger Moore as Simon Templar, was ‘The Organisation Man’ (1968).

9953.

Shelby Lyman on Fischer

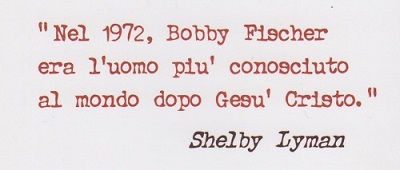

From the back cover of Tutte le partite di Bobby Fischer by Karsten Müller (Rome, 2011):

Whether Shelby Lyman ever made that specific assertion is unclear, but after about an hour of Liz Garbus’s 2011 documentary film Bobby Fischer Against the World (C.N. 7345) he did say to camera:

‘One of Fischer’s problems was that, after the match, he was supposedly better known by the population of the world than anyone except for Jesus Christ. And he was a guy who treasured his privacy. He had a problem.’

9954. Pictures of Capablanca and Alekhine, Buenos Aires, 1927 (C.N.s 4814 & 9944)

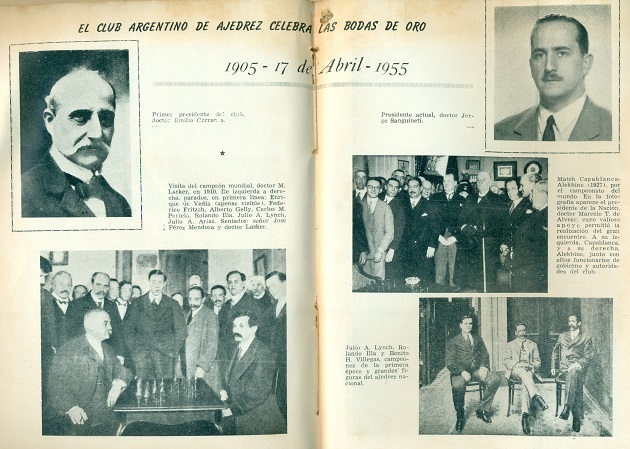

Marcelo Sibille (Montevideo, Uruguay) draws attention to a photograph on page 27 of the April 1955 issue of the Argentinian magazine Ajedrez:

9955. Photocopies

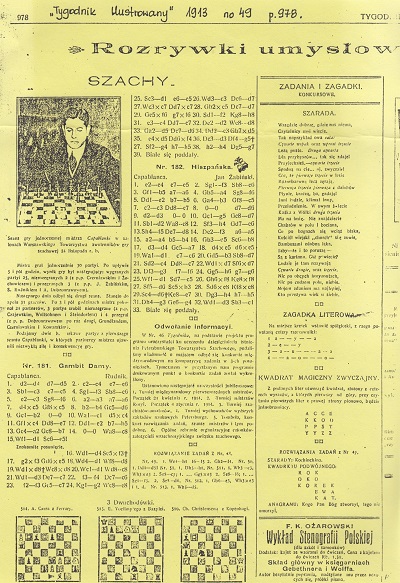

Any researcher is liable to accumulate mounds of photocopies (many barely identifiable or even legible, and rarely suitable for reproduction), but nowadays some of them may lead to valuable Internet resources. For example, in one of our mounds was this:

A run of the Polish publication Tygodnik Illustrowany is available on-line.

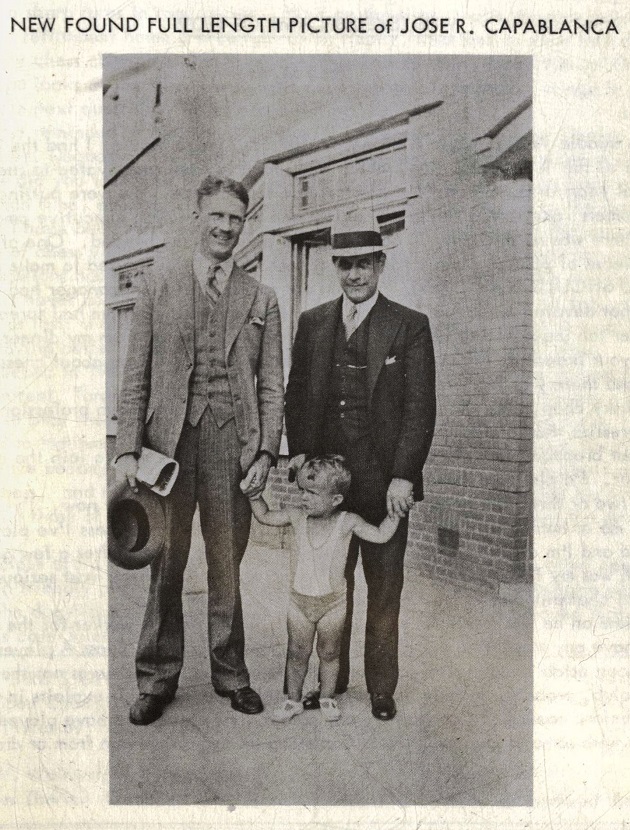

9956. Bower, Capablanca and Wren

Our archives also include a poor-quality photocopy of pages 169-170 of Canadian Chess Chat, August 1963, and we are grateful to the Cleveland Public Library for sending us the photograph on page 169:

From page 170:

‘Diplomats – Actual and Potential

Fred M. Wren

The attached photograph was taken by me in front of my 1931 home in Scheveningen, Netherlands.

The hatless, smiling gentleman on the left was the then Canadian Trade Commissioner to Holland, Dick Bower of Winnipeg. Although his playing strength in chess never quite reached mine, his diplomatic prowess far exceeded mine, and when I last heard from him a few years ago he was Canadian Ambassador to Argentina.

The gentleman on the right was, of course, Cuba’s gift to diplomacy and chess, Ambassador-without-portfolio and ex-champion of the world, José Capablanca. The hotel in which he made his headquarters for the match with Max Euwe was diagonally across from my home.

The child in the picture was my son, Bill, who eventually became very proficient in chess, gave it up for bridge, graduated from McGill in 1951, spent several years in Formosa, Laos and Thailand, and is now working on the Chinese Desk in the US State Department in Washington.’

9957. Hastings, 1895

On-line collections of images permit unexpected discoveries, such as an 1895 ‘Chess Masters at Hastings’ illustration (‘Ernest Prater’) in the LIFE photo collection. The players at the board appear to be Lasker and Pillsbury, but where has the picture been published?

9958. Caissa (C.N. 9945)

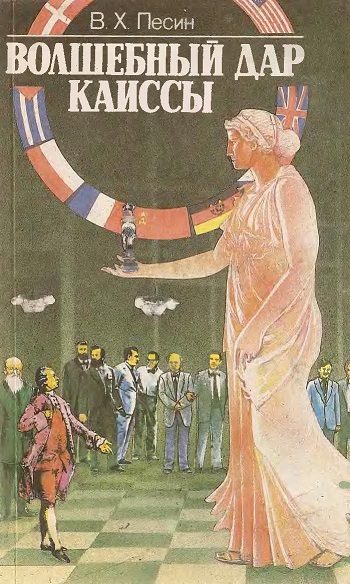

Vitaliy Yurchenko (Uhta, Komi, Russian Federation) mentions Волшебный дар Каиссы by V. Kh. Pesin (Leningrad, 1990):

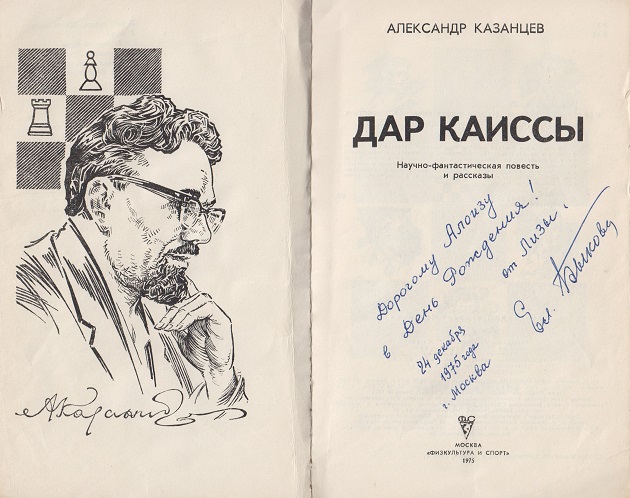

We also have Дар Каиссы by A. Kazantsev (Moscow, 1975):

Our copy was inscribed by Elisaveta Bykova to Alois Hruška on his birthday (24 December 1975):

9959. Fischer v Taimanov

Ewen McLaughlin (Betws, Wales) enquires about the position after 57 Ka6 in the fourth match-game between Fischer and Taimanov, Vancouver, 25 May 1971:

Most sources, old and new, have Taimanov’s move as 57...Ng8, but occasionally (e.g. in the 1976 and 1986 editions of Christiaan M. Bijl’s anthology of Fischer’s games) 57...Nc8 is given.

Can the discrepancy be resolved beyond all reasonable doubt?

9960. Fischer/Barden interview (C.N. 9831)

Recorded material from the 1960 Olympiad in Leipzig was included in the BBC radio programme about chess broadcast on Network Three on 23 April 1961, beginning at 16.00:

The BBC Written Archives Centre has informed us that the PasB (Programme-as-Broadcast) documentation merely states:

‘Interviews: (recorded at the Leipzig Chess Congress)

Between Leonard Barden

and various Grandmasters (NF).’

‘NF’ stands for No Fee, which means that the BBC did not enter into contracts with the interviewees and, therefore, did not list them individually on the PasB.

9961. Edouard Pape (C.N.s 4119 & 9910)

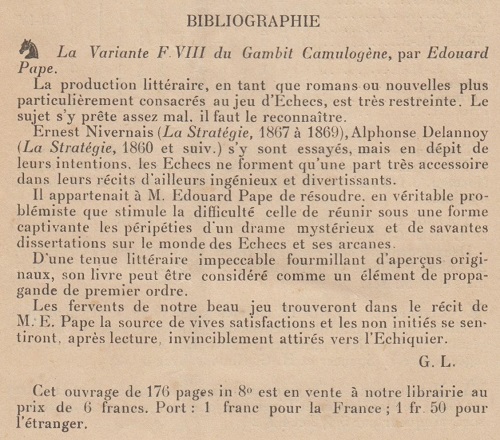

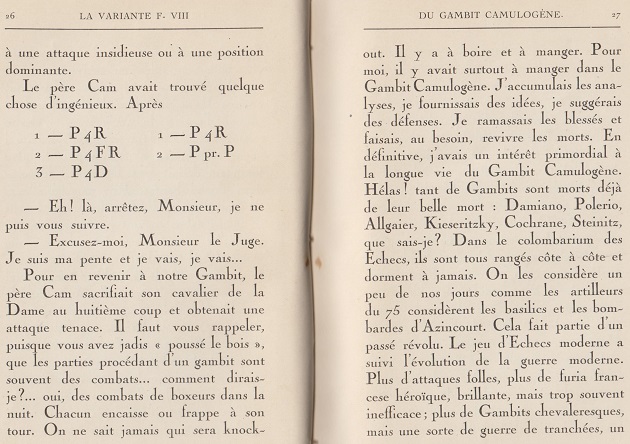

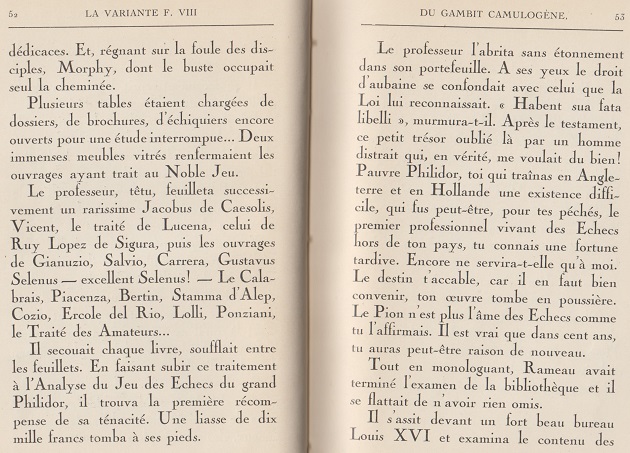

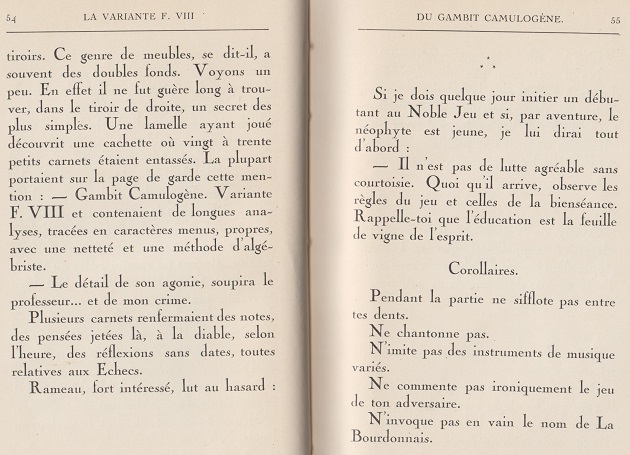

Page 16 of La Stratégie, January 1924 had a notice concerning La Variante F. VIII du Gambit Camulogène by Edouard Pape (Paris, undated):

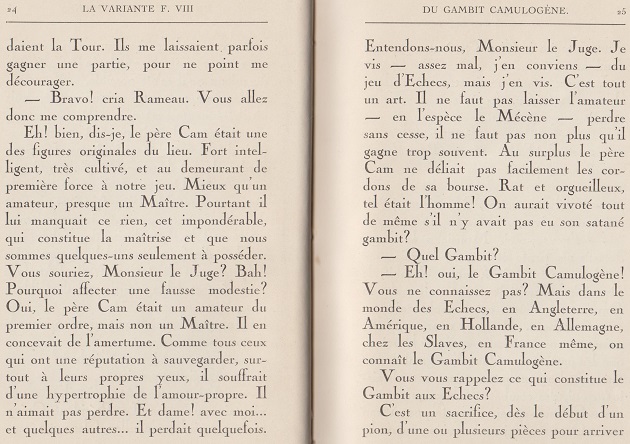

A few pages from our copy of this scarce novel:

9962. The Chess Amateur and Punch

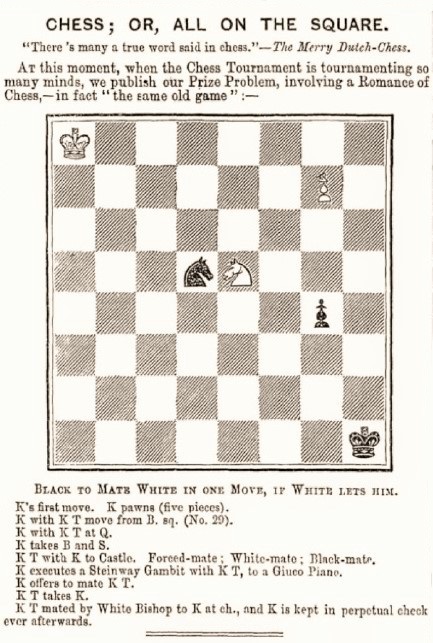

From page 355 of the Chess Amateur, September 1916:

‘The Funniest Chess Joke

The chess jokes of our venerable contemporary Punch have been few and far between, and naturally so, for he caters to a public of which but a small percentage would appreciate jokes that may raise a smile among readers of a chess magazine. We do not remember any very good chess joke in Punch and doubt if any could be perpetrated that would be thought suitable by its editor. Perhaps the funniest was one of many years ago: a chess position was printed on a diagram, not, we fancy, a genuine problem, with the inscription: “White to move and mate in two moves, if Black lets him”.’

The following was on page 228 of Punch, 12 May 1883:

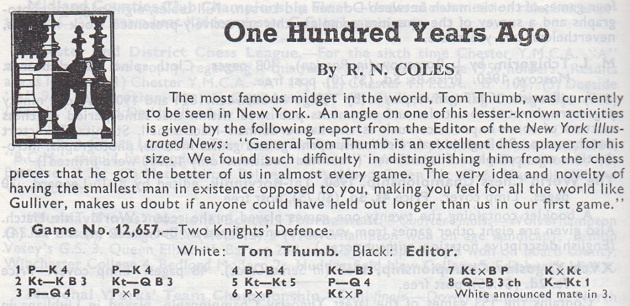

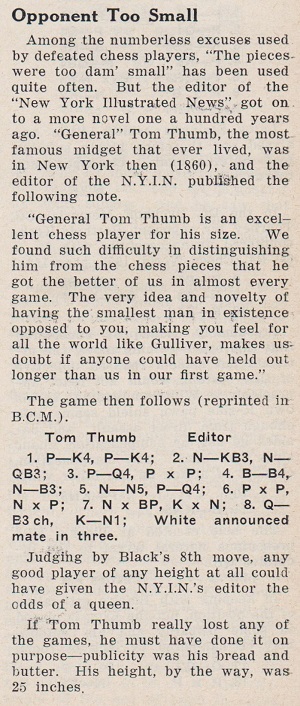

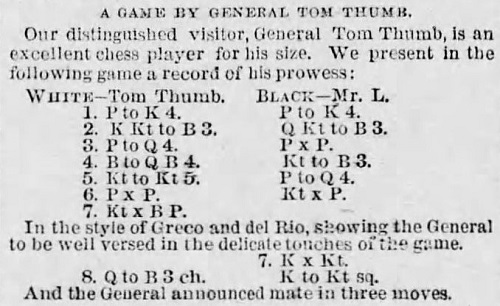

9963. Tom Thumb (C.N.s 3931 & 4323)

C.N. 4323 mentioned a vague reference to ‘the Editor of the News’ in connection with a game ascribed to Tom Thumb. The publication was the New York Illustrated News (whose chess columnist in 1860 was Sam Loyd), as shown by R.N. Coles on page 200 of the July 1960 BCM:

The item was picked up by Chess World, July 1960, page 127:

Can the New York Illustrated News feature about Tom Thumb be found?

9964. The threat is stronger than the execution

C.N. 3197 (see A Nimzowitsch Story) quoted a remark by Tartakower on page 373 of issue 28 of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français (1932):

‘1. Puisque “la menace est plus forte que l’exécution”, il n’est pas paradoxal de prétendre qu’il est plus fort de ne pas user de la menace. Qu’on appelle cette stratégie “louvoiement”, “jeu positionnel” ou “stratégie d’attente”, c’est une façon de jouer qui est très pratiquée dans les grands tournois et qui donne souvent de bons résultats, car il peut en résulter chez l’adversaire une moindre vigilance. Elle peut, en outre, lui faire perdre patience et le pousser à s’élancer dans une attaque prématurée.’

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) notes that the article had previously appeared on pages 132-134 of El Ajedrez Americano, May 1931, with this slightly different text on page 134:

9965. Rousseau

An addition concerning Jean-Jacques Rousseau comes from an article entitled ‘Le Chevalier de Barneville’ by Joseph Méry on pages 117-120 of La Régence, April 1851:

‘En 1768, au coup de midi, vingt ans avant la révolution, le jeune chevalier de Barneville entrait au café Procope et jouait avec Philidor et Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Les beaux esprits du temps formaient galerie, et les graves encyclopédistes, le menton appuyé sur les pommes d’or de leurs cannes, suivaient la marche des parties, et critiquaient le jeu de Philidor, parce que les encyclopédistes critiquaient tout. Un jour, en présence de M. Saint-Amand, qui a été gouverneur des Tuileries en 1848, du général Guingret, alors commandant de l’Ecole militaire, et de M. Devinck, aujourd’hui président du tribunal de commerce de Paris, Labourdonnais engagea un entretien fort curieux avec le chevalier de Barneville.

“Parlons un peu de l’histoire ancienne, mon cher chevalier; comment jouiez-vous avec Philidor?

– Il me donnait le cavalier et le pion.

– J’aurais donc donné, moi, le pion et deux traits à Philidor?

– Sans doute.

– Et quelle partie faisiez-vous avec Jean-Jacques Rousseau?

– Je lui donnais une tour.

– Il était donc bien faible.

– Mais, en revanche, dit le chevalier, il avait un amour-propre colossal, et le plus affreux caractère de joueur d’échecs qui ait existé. Comme il avait la manie de se croire grand mathématicien et de faire de la musique avec des chiffres, il voulait appliquer les calculs algébriques à l’échiquier. Nous le plaisantions fort là-dessus, et alors il brouillait toutes les pièces du jeu avec une certaine rage peu philosophique, et on ne le voyait plus au café pendant quinze jours.”’

9966. Editors, players and problemists

From the chess column of T.P. Bull on page 3 of the Detroit Free Press, 22 August 1875:

‘The chess editors contribute more to the cause of the game than nine-tenths of the players who may outrank them in playing skill but not in a quick appreciation of what the improving players and problem solvers want.’

Quoting the remark, W.N. Potter commented on pages 267-268 of the October 1875 City of London Chess Magazine that it raised ‘what we may call a false issue’:

‘This is equivalent to saying that gas is useless without the means of lighting it, which is true enough; but a lucifer-match is not therefore more important than a gasometer. Without first-class players and fine problemists of what use are editors? To use another and perhaps better illustration, the latter are like tradesmen, whose business is to vend the articles which the customers want. It is the tradesman’s duty and interest to sell good articles, but if he cannot get them he may shut up shop.’

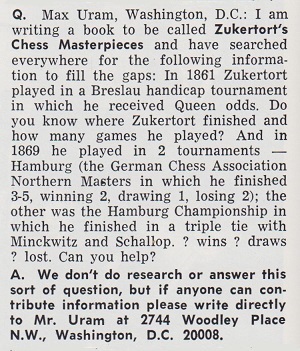

9967. ‘We don’t do research’

From the ‘Larry Evans on Chess’ column on page 208 of Chess Life & Review, April 1971:

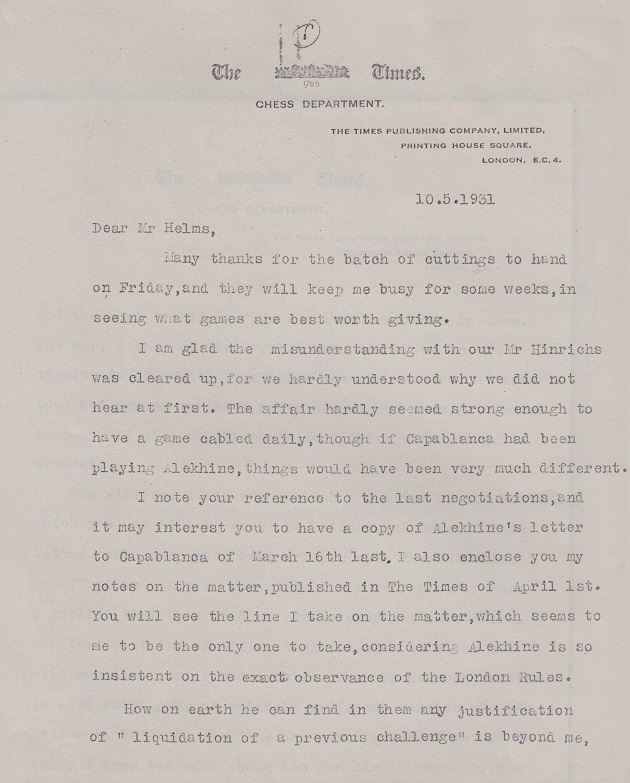

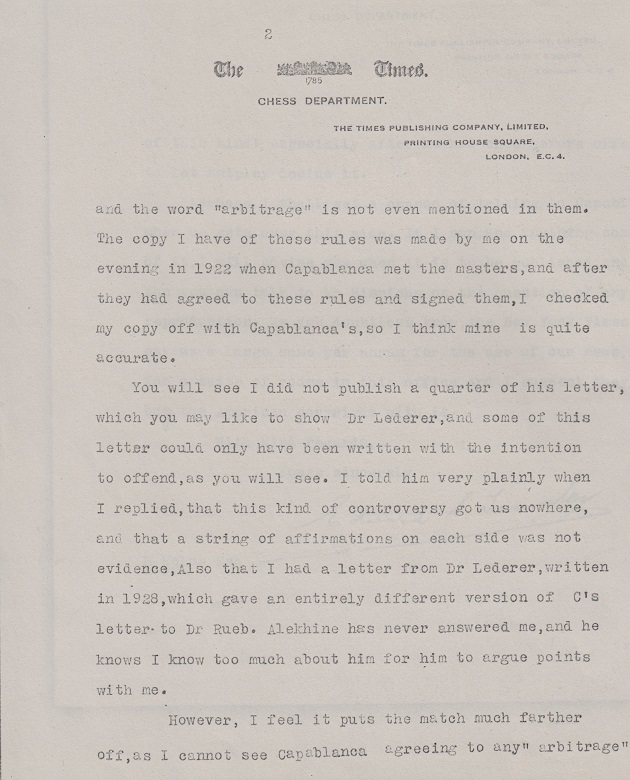

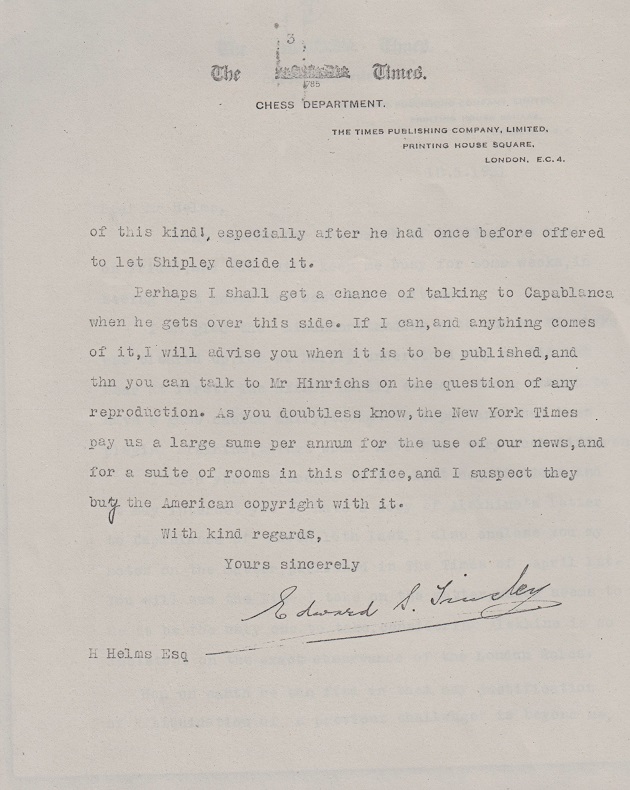

9968. A Tinsley letter to Helms

Another photocopy from our mounds (C.N. 9955) is a letter dated 10 May 1931 from E.S. Tinsley to Hermann Helms:

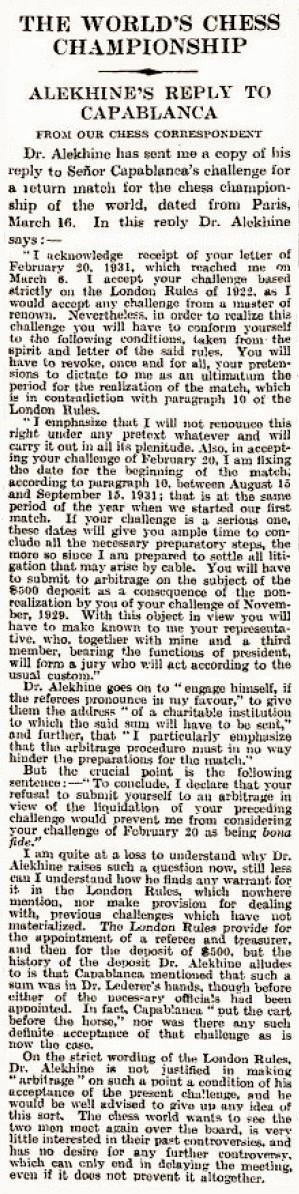

Alekhine’s letter of 16 March 1931 to Capablanca was given on pages 227-228 of our book on the Cuban. Below is the report on page 12 of The Times, 1 April 1931:

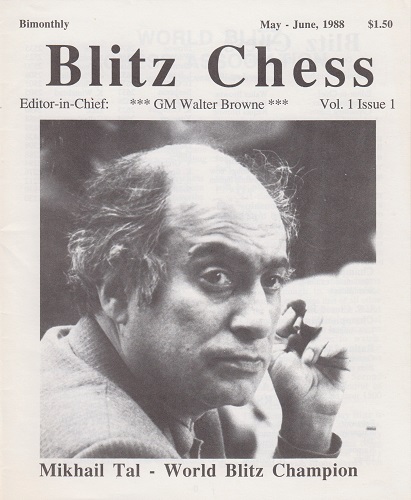

9969. Blitz chess

‘Chess is the most creative, fascinating and challenging game there is; and the most exciting spine-tingling form of chess is Blitz.’

Source: Walter Browne on page 1 of the first issue (May-June 1988) of his magazine Blitz Chess.

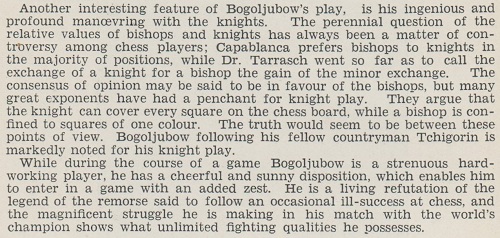

9970. Preferred pieces

Comments about players’ preferred pieces are of interest if considered with circumspection. From page 40 of Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929):

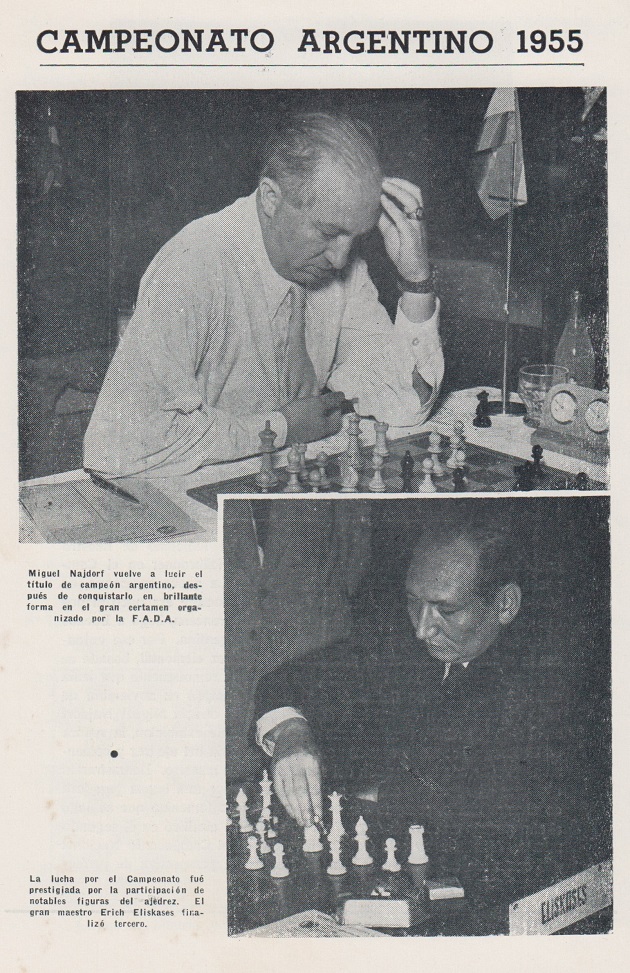

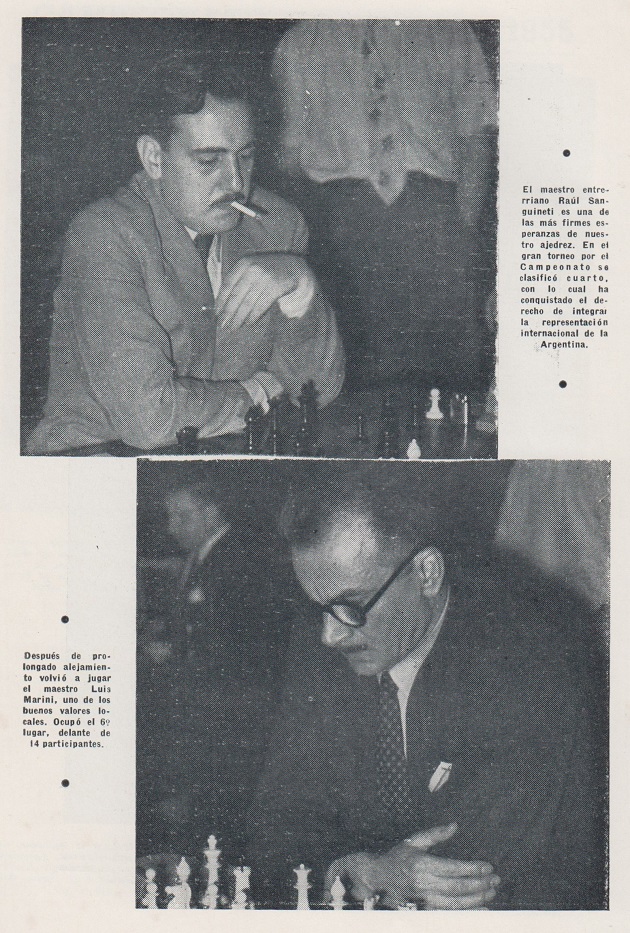

9971. 1955 championship of Argentina

Photographs of Miguel Najdorf, Erich Eliskases, Bernardo Wexler, Héctor Rossetto, Raúl Sanguineti and Luis Marini on pages 18-20 of the Argentinian magazine Ajedrez, January 1956:

9972. Pictures and documents on-line

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) points out that the library of the Jewish Theological Seminary has high-quality pictures of Löwenthal and Reshevsky, and that a search for ‘Jacques Mieses’ at the website of the Leo Baeck Institute, Center for Jewish History yields a number of letters written by him, in the Hanna de Mieses Family Collection, 1833-1981.

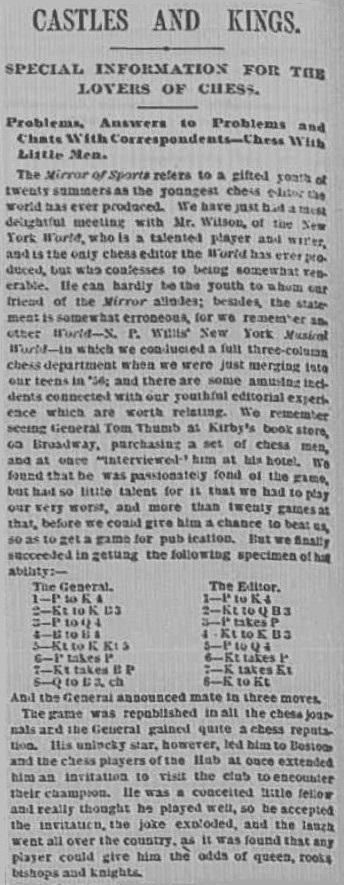

9973. Tom Thumb (C.N.s 3931, 4323 & 9963)

The game’s appearance on page 7 of the Philadelphia Times, 8 October 1882:

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) draws attention to background information written by Sam Loyd in his column on page 6 of the New York Evening Telegram, 3 July 1885:

Loyd’s comments about his early start as a columnist are relevant to our feature article The Caissa-Morphy Puzzle.

9974. The Evening Telegram

Steinitz on page 114 of the International Chess Magazine, April 1885:

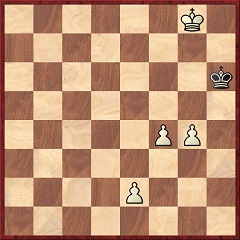

9975. Teed composition

White to move

Information about this composition is sought. At present we can say only that it was ascribed to Frank M. Teed, without a source or date, on page 12 of Ideal-Mate Chess Problems by Eugene Albert (Davis, 1966).

9976.

Alekhine v Bogoljubow

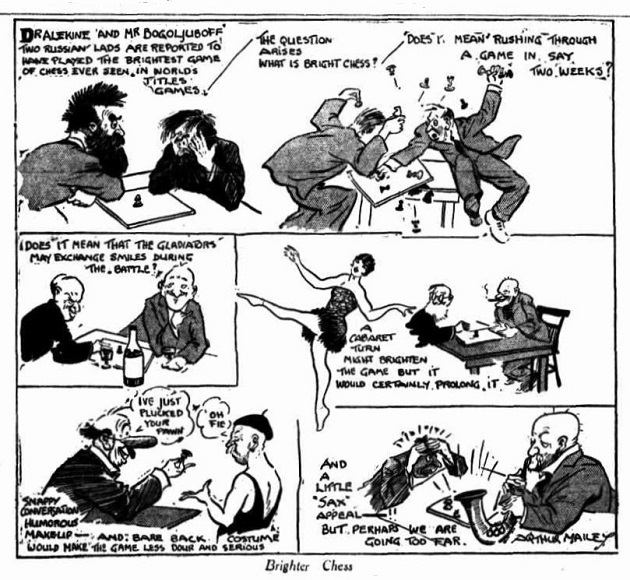

Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) provides a cartoon from page 8 of the Sun (Sydney), 30 October 1929:

The cartoonist, Arthur Mailey (1886-1967), was an Australian test cricketer.

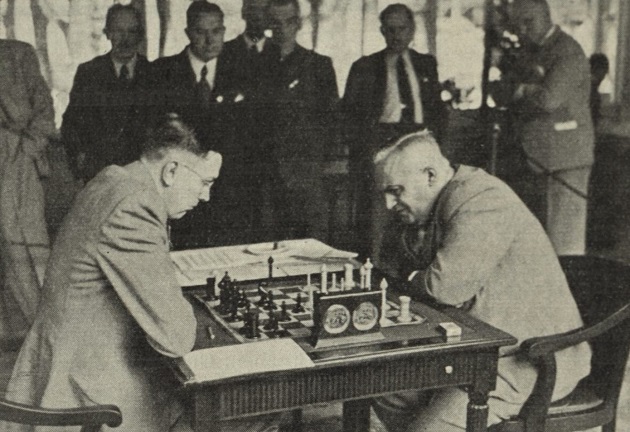

9977. Euwe v Bogoljubow match, Carlsbad, 1941

A photograph published on page 114 of the August 1941 Deutsche Schachzeitung is shown here courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library:

9978. Madrid, 1943 tournament

A Spanish website has a large number of chess photographs. One recommended search, ‘ajedrez 1943’, gives these 12 shots:

9979. Korchnoi and Anti-Chess

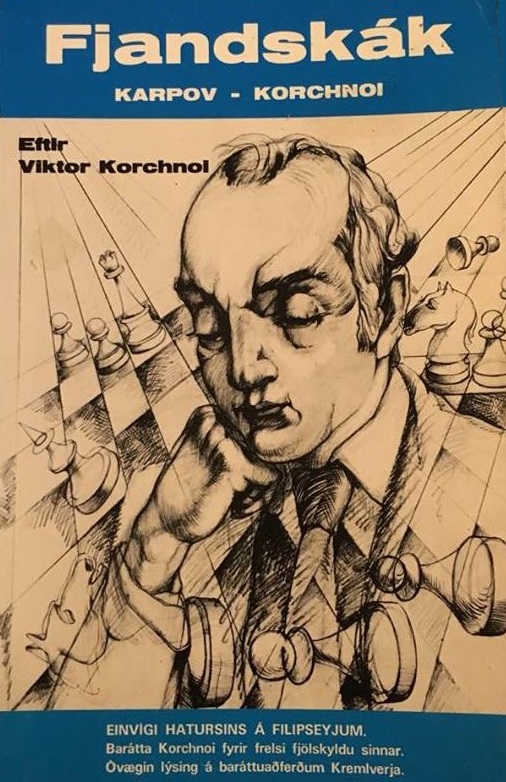

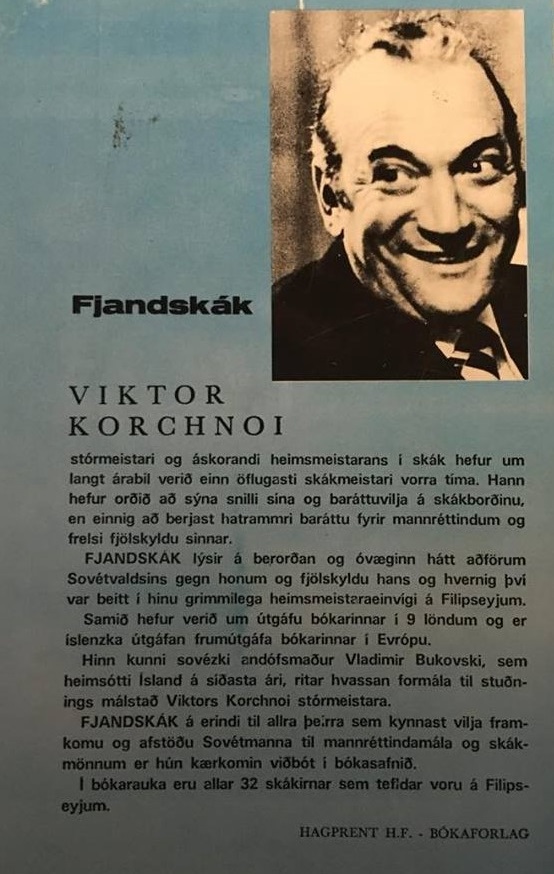

Our feature article on Victor Korchnoi includes references to his book Antischach (Wohlen, 1980). Apart from the editions mentioned, there is a Spanish translation, Anti-ajedrez (Buenos Aires, 1980), and page 489 of the November 1981 BCM stated that ‘Korchnoi’s book has appeared in English in Iceland’.

We cannot corroborate that, but certainly an Icelandic translation of Antischach exists, published in 1981. These images come from Aðalsteinn Thorarensen (Reykjavik):

9980. Karpov on Korchnoi and chess writers

As quoted in C.N. 1322, pages 73-74 of From Baguio to Merano by A. Karpov and V. Baturinsky (Oxford, 1986) had these remarks by Karpov:

‘Since the question has arisen about people writing on chess, I will permit myself to say a few words regarding this. Many of those who came to Baguio as correspondents for their papers had altogether not the slightest connection with our game, and in fact this is one field where it is extremely difficult to get by without a minimum of special knowledge. The correspondent of the Hamburg Welt wrote in his newspaper with disarming honesty: “To tell the truth, for me chess is an unknown sphere, but, as I understand it, in Baguio we are witnessing not only the moving of wooden pieces.” These journalists were seeking something quite different at the match – as a matter of fact, the play did not concern them. It stands to reason that neither I nor anyone else can advise who should be entrusted with writing about such a significant event as a match for the world chess championship. This is a matter for each individual publication. But genuine chess connoisseurs and enthusiasts have the right to judge as they will material written in obscure (because they do not know the subject) language, lacking in chess content, and full of citations from pronouncements by Leeuwerik, in which only one tendency is apparent – antipathy to everything Soviet, to everything which is not pro-Korchnoi. Yes, during competitions I endeavour to withdraw into myself, and to concentrate on my main duty – which is to play well at chess, whereas Korchnoi constantly “feeds” the journalists, swarming like bees round a honey-pot. And those of them who altogether had no knowledge of our game described in especially vivid terms any pronouncements by the grandmaster who had defected from the Soviet Union – since this in itself was a sensation, and everything associated with it was readily published by the papers. But where does chess come into all this?

There is another, perhaps even more refined, method of forming public chess opinion. Immediately after the match, in fearful haste dictated by purely opportunist considerations (the market demands it!) a whole series of books devoted to the match were written. The quality of the overwhelming majority of them leaves a great deal to [be] desired. But in the end, grandmaster Keene, for example, might retort that, being on the staff of the Challenger, he could see for himself what was happening on the board, since he participated in the work of one of the two chess laboratories. Bent Larsen, although he was not present at the match, would reply that his chess strength enables him to analyse chess games even at a distance. But then I made the acquaintance of an analysis of the match games in a book by William Hartston, and it immediately became clear why this player, who for a long time promised to become the first English grandmaster, continues to remain an ordinary master. The superficiality of his subjective comments is beneath all criticism.

What forced me to speak about all this was by no means a desire to express my opinion, but solely my concern for the future of chess, and for the interests of chess enthusiasts, who can improve their play only from objective analytical material. My chess strength and, I hope, my popularity, nevertheless do not yet depend completely on the description of this or that journalist, or on the analysis of low-class players.’

9981. Fantasy

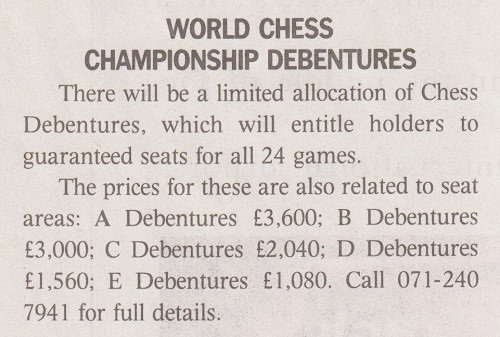

Page 12 of The Times, 18 May 1993 had a full-page advertisement headed ‘25,000 1993 world championship chess bonds’ which included this offer:

On page 17 of the same edition, chess was the subject of the main leading article:

Already the opening paragraph was drivel:

‘There is an essential connection between chess and journalism: both are attempts to place some sort of order on a shifting world. But there is a special connection between chess and The Times, the newspaper that has been at the heart of recording, managing and teaching the game throughout its history.’

There was much familiar old patter, such as this:

‘The cultivation of positional play by Wilhelm Steinitz in the latter half of the nineteenth century was influenced by parallel changes in military technique, which eventually led to trench warfare.’

Over the subsequent months, coverage became increasingly frantic and mendacious. From our reading, no newspaper’s treatment of chess has ever attained the level of crassness found in The Times throughout 1993. The feature article Cuttings shows many examples, and more will be added in due course.

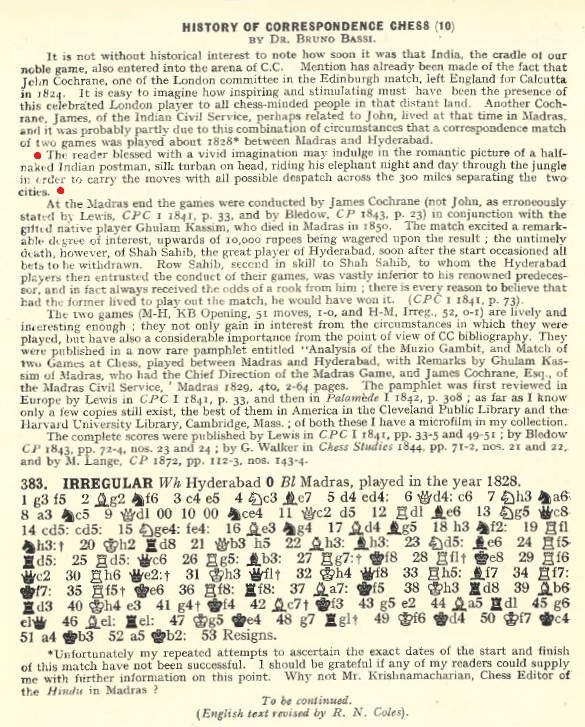

9982. Elephants

Concerning Indian Openings in Chess, Martin Sims (Upper Hutt, New Zealand) points out a remark in Ghulam Kassim’s annotations to the second game in the Madras-Hyderabad correspondence match, after 1 g3:

‘Many of the Indian Players commence their Game in this way.’

Source: page 45 of Analysis of the Muzio Gambit, and Match of Two Games at Chess, Played Between Madras and Hyderabad by Ghulam Kassim and James Cochrane (Madras, 1829). The book can be read on-line.

Our correspondent asks for information about a sourceless assertion by Andrew Soltis that elephants conveyed the chess moves. On page 10 of Chess Life, January 1990 Soltis wrote:

‘Take the case of the two-game match played more than 160 years ago between the masters of the Bay of Bengal port of Madras and the best players of Hyderabad, some 300 miles up into the interior of India. The surest way of sending the moves back and forth was via the regular mail pouches – that is, the ones carried by elephants.’

And:

‘The 2-0 victory by Madras is almost forgotten by history but should be remembered as The Elephant Match.’

A recent account of the contest is on pages 166-172 of volume one of L’histoire du jeu d’échecs par correspondance au XIXe siècle by Eric Ruch (Aachen, 2010). From pages 166-167:

‘Le lecteur imaginatif peut se représenter l’image romantique d’un postier indien à demi-nu, enturbanné, juché nuit et jour sur un éléphant, pour couvrir à travers l’épaisse jungle, les 300 miles de distance séparant les deux cités, pour y acheminer les coups d’échecs de nos joueurs par correspondance.’

The text, which was not in quotation marks, had a footnote mentioning an article by Bruno Bassi on page 327 of Mail Chess, March 1949. Courtesy of the Royal Library in The Hague, it is shown here:

The article was included in the collection of Bassi’s writings, The History of Correspondence Chess up to 1839 compiled by Egbert Meissenburg (Winsen/Luhe, 1965). An Italian translation, by Enzo Minerva, was published as a supplement to the 5/1991 issue of Telescacco nuovo, Rome under the title Storia del gioco per corrispondenza fino al 1839.

The correspondence match of the late 1820s was discussed on pages 31-33 of Indian Chess History 570 AD-2010 AD by Manuel Aaron and Vijay D. Pandit (Chennai, 2014). Page 31 stated:

‘An unlikely story is that the moves were despatched by golden caparisoned elephants carrying a private postman wearing a crimson turban and pearl-grey livery holding a blue lantern.’

From page 18 of Western Chess In British India (1825-1947) by Vijay D. Pandit (Nottingham, 2011):

‘We know that the moves were transported by liveried servants riding on the back of elephants ...’

The statement is unsubstantiated. We prefer to be told how we know what we are told that we know.

Have writers’ references to transportation by elephant merely misused Bruno Bassi’s light-hearted fancy beginning ‘The reader blessed with a vivid imagination may indulge in the romantic picture of ...’, or is there documentary evidence?

9983. Bruno Bassi (C.N.s 7124 & 9982)

D.J. Morgan’s obituary of Bruno Bassi on page 163 of the June 1957 BCM:

9984. Fischer/Barden interview (C.N.s 9831 & 9960)

From Leonard Barden (London):

‘My clear recollection of the recordings which I made during the 1960 Olympiad is that they were not really interviews in the normal sense, but informal memory tests, seeking recall of one or two key moments from the games of others and one or two from the subject’s own play, with a few supplementary questions arising from the flow of the conversation.

Before the British Chess Federation team left for Leipzig, the BBC issued me with a heavy tape-recorder, which I carried over my shoulder and which was an extra to my suitcases. They housed thick loose-leaf volumes of handwritten openings data plus what turned out to be the most valuable item of all: a copy of the latest Deutsche Schachzeitung, which the postman delivered just as I was leaving the house. It contained the Ojanen v Keres game (Modern Benoni) that Jonathan Penrose consulted to effect on the morning of the final round before his game with Tal.

After I arranged interview times with the subjects in Leipzig, I found that the tape recorder batteries no longer functioned. So I went to the Leipzig branch of GUM, the main department store chain then in Eastern Europe, and bought replacements. These did not work either. I then arrived at the local radio station. As I hoped, it was impressed to have a visitor from the BBC, and it took pleasure in providing me with working batteries. Somewhat daring in the ambiance of the time, I ventured a political joke: capitalist batteries did not work, but communist batteries were no better. This was well received, and we parted amicably.

The subjects of the quasi-interviews included Tal, who had the best memory of all, as one would expect from other well-known reports around that time of his phenomenal powers of recollection. Choosing a game from his youth, I asked about his loss to Lev Aronin at Riga, 1954. In retrospect, this was probably not a good test choice since the game was noteworthy as an early example of the Tal sacrificial style, taking on the Caro-Kann and sacrificing a bishop at e6 and a knight at g5 to keep the black king in the centre, before missing a probable win by 17 Rxe5+. Tal responded by repeating the pre-game banter between the players, the course of the game itself, and a further conversation with Aronin at the post-mortem. He also had excellent recall when I asked him about games by a couple of other grandmasters.

Korchnoi received me at noon when he was still in bed, smoking, and told me amid coughs that he used one-mile runs for physical training, a claim which provoked my scepticism but, of course, was perfectly true. His memory test performance was quite good.

Gligorić surprised me negatively since I had assumed that as a highly professional and dedicated chess worker he would have a good memory. In fact, he had poor recall even of his own games.

Finally, Fischer had a good memory of a couple of his early games from the mid-1950s, but could recall little when I asked for his recollections of games by his rival Reshevsky.’

The famous Penrose v Tal game referred to by Mr Barden was annotated by Penrose on pages 360-362 of the December 1960 BCM. After 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 c5 4 d5 exd5 5 cxd5 g6 6 e4 d6 7 Bd3 Bg7 8 Nge2 he wrote:

‘I was aware that these moves had been played earlier in the year in a game Ojanen-Keres, and although I could not recollect the further course of the game very well, I thought that a variation good enough to lead to the defeat of Keres must be a very good one.’

The Ojanen v Keres game, played in a match between Finland and Estonia (Helsinki, 15 May 1960), had been published on page 224 of the July 1960 Deutsche Schachzeitung with notes by Eero Böök. Two books which discuss it, as well as Penrose’s victory over Tal, are Ojasen oival luksia by K. Ojanen and V. Salonen (Toijala, 1975) and Kaarle Ojanen – elämä ja pelit by H. Hurme, I. Kanko, J. Norri and P. Saharinen (Helsinki, 2009). See, respectively, pages 67-71 and pages 174-177.

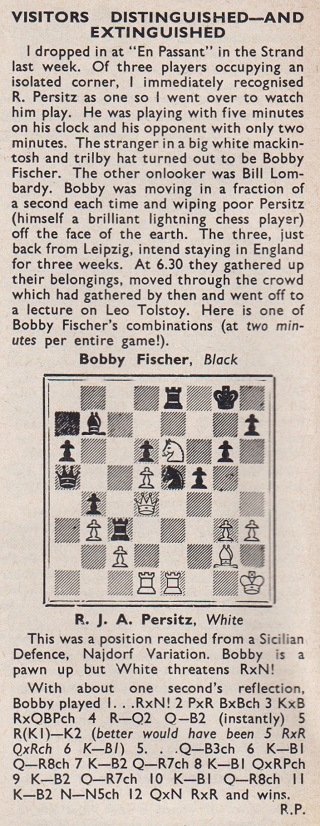

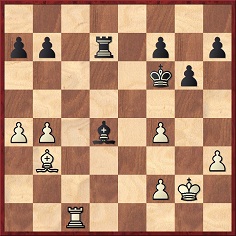

9985. Persitz v Fischer, London, 1960

From page 106 of CHESS, 10 December 1960:

9986. C.J.S. Purdy on Florencio Campomanes

In a report on the Melbourne Olympic Tourney, 1956-57 C.J.S. Purdy wrote about Florencio Campomanes on pages 9-10 of Chess World, January 1957:

‘We believe it was largely through his efforts that the Philippines has been the scene of an extraordinary mushroom growth in chess absolutely without parallel in the world’s history. He is a lecturer at the National University but temporarily resigned to go to Moscow and afterwards Melbourne. He lived seven years in the USA.

Through most of the tourney he seemed more sinister than genial, but he was putting on an act; it seemed that he deliberately set out to irritate his opponents as a matter of tactics. At the prizegiving he disclosed his view that friendly chess is one thing and tournament chess another – more or less apologizing for his gamesmanship. The answer is that in most countries, including Australia, players tacitly agree not to use gamesmanship, and everybody plays ruthlessly but follows a strict code of behaviour.

We must add our opinion that Campomanes gained absolutely nothing by his irritation tactics – mostly of a mild and to us rather amusing kind – and that he upset nobody’s nerves more than he did his own.

The moment the tourney was ended, he ceased walking around like a wounded rhinoceros, and became a very genial fellow. He is a rather overpowering character, but his driving force has been used to great effect in the service of chess – we hope to meet him again when we have time to talk. On this occasion we were representing rival newspapers in Manila and had no time for idle chat between games. He may be surprised at our candour, but we remind him of a snatched conversation as we passed each other one day.

Campo: You seem to be taking your chess writing very seriously.

Purdy: It’s my profession.

Campo: Mine, too.

Purdy (realizing he had been misunderstood): Not chess, I mean writing.

Now, a professional writer must be candid. And we really think Campomanes would be insulted if we plastered him with insincere eulogy. Suffice it to say that he made an indelible impression. He was certainly the strongest of the three Filipinos at chess [the others were R. Cardoso and J. Pascual], and well deserved fourth prize, which, as he said at the prizegiving, he cherished far beyond the value of £A35 or its equivalent in pesos.

He is to be congratulated on doing so well in spite of the burden of press work. For he took his newspaper work quite seriously, even though in jest he might have seemed to disclaim it.’

Page 99 of the April 1957 Chess World gave the conclusion of Campomanes’ victory in round seven of the Melbourne tournament over C.J.S. Purdy’s son, John, after 29...Kg7-f6:

30 Kf3 Bc5 31 bxc5 Rd3+ 32 Ke4 Rxb3 33 c6 bxc6 34 Rxc6+ Kg7 35 Ra6 Rxh3 36 Rxa7 Ra3 37 a5 h5 38 f5 g5 39 Ra8 h4 40 f3 h3 41 f6+ Kh7 42 Rb8 Rxa5 43 Rb1 Kg6 44 Ke3 Ra2 45 Ke4 h2 46 Ke3 Rg2 47 Rh1 Kf5 48 White resigns.

That item in Chess World was headed ‘End-Game Suicide’, with criticism of White’s 30th and, especially, 32nd moves. We have yet to trace the full game-score.

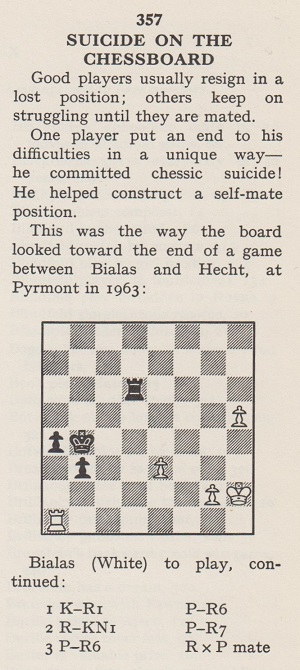

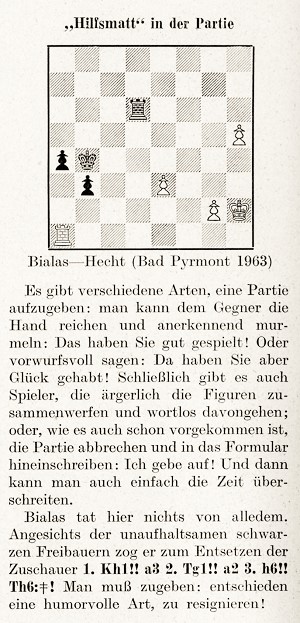

9987. ‘Suicide on the Chessboard’

From page 193 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974):

The full game is available in databases, and the conclusion was discussed on page 12 of the Deutsche Schachzeitung, January 1964:

Have any other players given up the ghost in such a way?

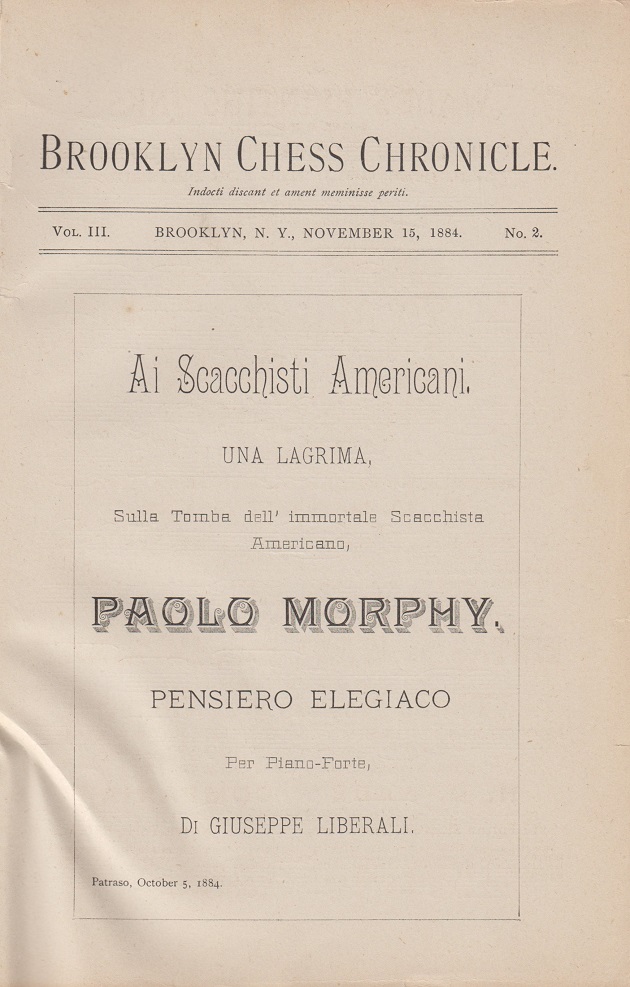

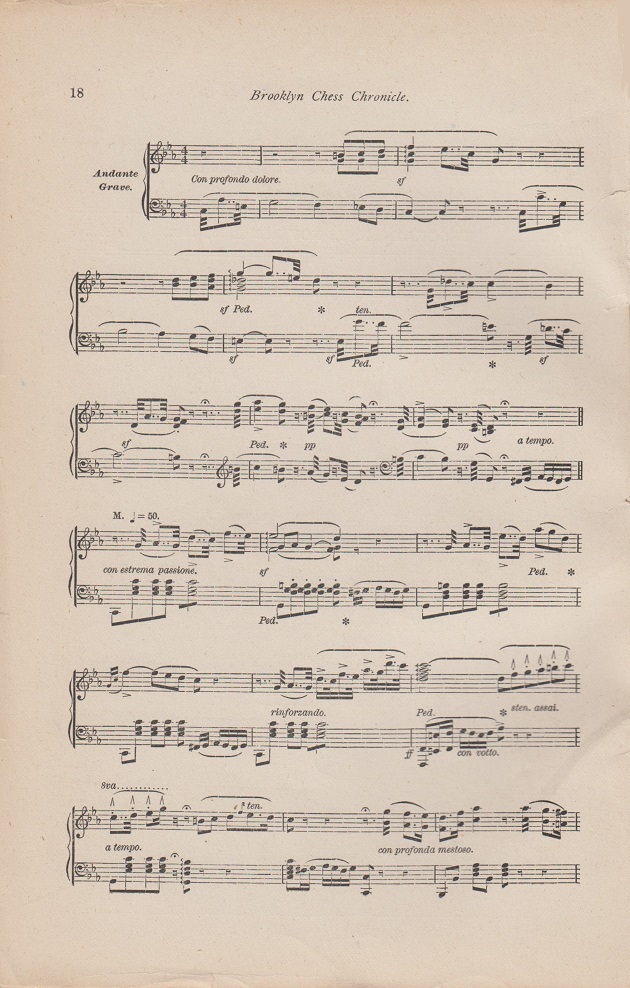

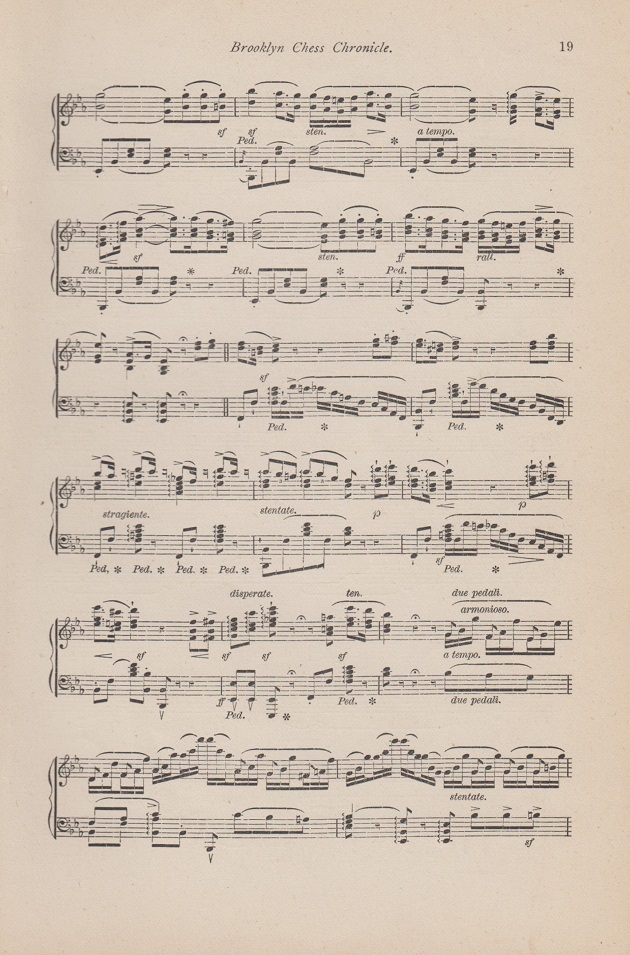

9988. Morphy piano elegy

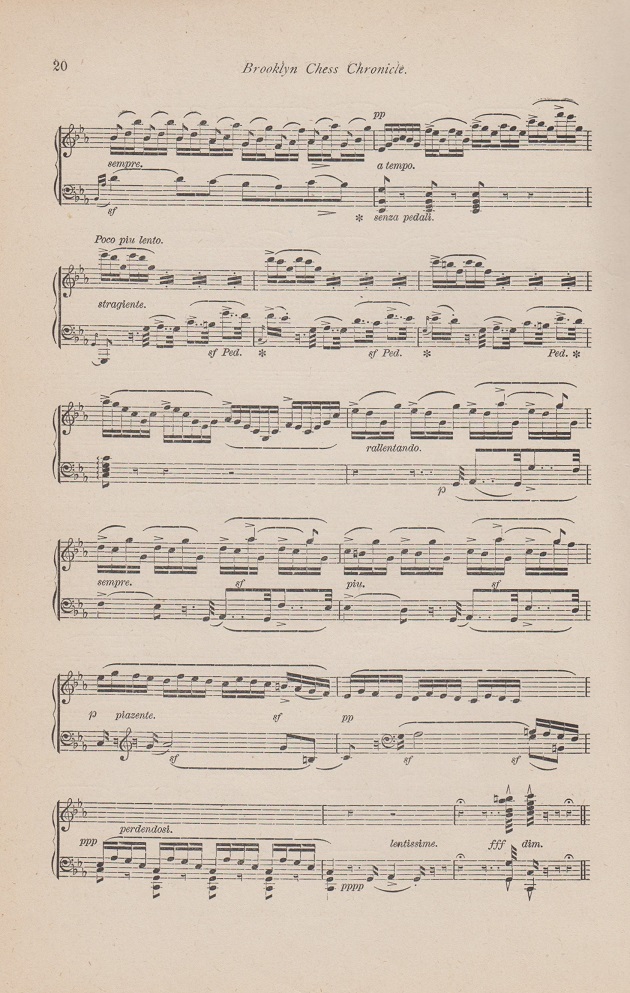

Pages 17-20 of the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 15 November 1884 published Ai Scacchisti Americani, Una Lagrima Sulla Tomba dell’immortale Scacchista Americano, Paolo Morphy by Giuseppe Liberali:

9989. Arthur Mailey (C.N. 9976)

Further chess cartoons by Arthur Mailey have been found by Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) in the Sun (Sydney), 15 April 1923, page 13; the Sun (Sydney), 6 May 1924, page 4; the Newcastle Sun, 24 August 1933, page 8.

Our correspondent also points out a brief article by Mailey, ‘Training in Secret’ (the Newcastle Sun, 10 September 1935, page 2), concerning the Alekhine v Euwe world championship match.

9990. Frequent bad play by a genius

From page 53 of Chess Strategy and Tactics by F. Reinfeld and I. Chernev (New York, 1933):

‘It is doubtful whether any player of Richard Réti’s genius has ever succeeded in playing as badly as Réti often did ...’

9991. Fischer v Taimanov (C.N. 9959)

Evidence in support of Taimanov’s move being 57...Nc8, as opposed to 57...Ng8, has not been found. Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) notes that, for instance, the June 1971 issue of Northwest Chess gave 57...Ng8 (see page 9).

However, the magazine then had 58...Ne7, 59...Kc6 and 60...Kc7. As Ewen McLaughlin (Betws, Wales) points out, that sequence is on page 369 of Profile of a Prodigy by Frank Brady (New York, 1973) but the other books consulted put 58...Ne7, 59...Nc6 and 60...Ne7.

9992. Persitz v Fischer, London, 1960 (C.N. 9985)

From Leonard Barden (London):

‘The writer in CHESS, ‘R.P.’, was probably Roland Payne, a strong blitz player and a regular at the “En Passant” in the Strand. He had an excellent kibitzer memory and was well capable of reconstructing the Persitz v Fischer fragment.

The reference to Fischer going to a Tolstoy lecture may sound odd, but 20 November 1960 was the 50th anniversary of the death of the Russian writer (and chessplayer), and there were lectures in both England and the United States to mark the occasion. The academic Isaiah Berlin recorded one such lecture for the BBC on 23 November.’

9993. Golombek on chess problems

Jacob Bronowski and Chess refers to Harry Golombek’s self-centred ‘tribute articles’ on page 13 of The Times, 5 October 1974 and pages 441-443 of the December 1974 BCM. An episode related in both publications dates from the late 1920s:

‘... on holiday at a seaside resort on the southern coast I had a number of conversations with a worried looking gentleman in my boarding house while the rain was falling. This was Bronowski’s father, and the reason why he was worried was that he was full of forebodings about his son’s tendency to dissipate his undoubted gifts on what seemed to him mere side-issues. He was writing poetry and, as for chess, he was giving too much time to chess problems. “A waste of time”, I commented in the full certainty of my 17 years. “Yes”, said Bronowski père, “that’s what I’m always telling him.”’ (Times)

‘... he asked for my advice about his son. He was at Cambridge University and, according to the father, dissipating his undoubted talents in all sorts of unrewarding side-issues. He was even writing poetry and as for chess, he had recently taken up problem composing instead of the more solid pursuit of actually playing chess. What, he asked, did I think of chess problems. “A waste of time”, I replied. Before there are howls of protest, let me add that I have learnt better now. I consider problems just as much, or as little, waste of time as playing chess, going in for politics or religion, practising the law or train-spotting, negotiating to enter or leave the EEC or just simply, like Candide, cultivating one’s garden. Anyway, my reply appealed to Bronowski père, who said, “That’s what I’m always telling him.”’ (BCM)

Golombek’s writings throughout his life showed little interest in chess compositions.

9994. Zugzwang

Zugzwang sets out some authorities’ disagreement over the precise meaning of the German term in descriptions of chess play, but which games are most likely to be accepted as ‘ideal’ illustrations?

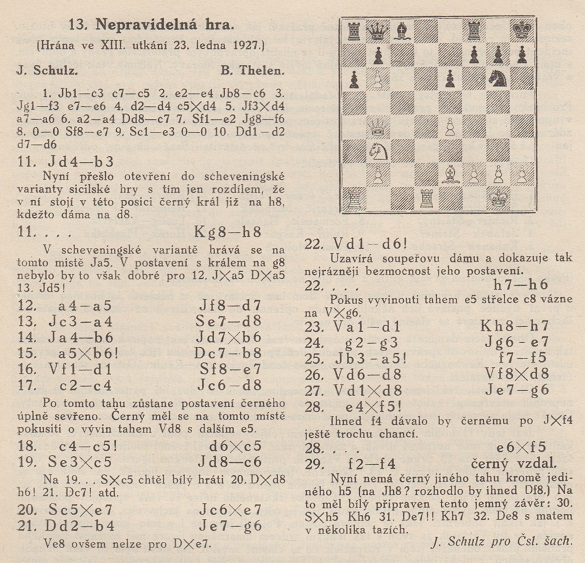

On the inside front cover of the June 1951 Chess Review Irving Chernev gave the game Jan Schulz v Bedřich Thelen, Prague, 1927, introduced as follows:

‘Even the great Houdini could not have wriggled out of this paralyzing Zugzwang.’

1 Nc3 c5 2 e4 Nc6 3 Nf3 e6 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 a6 6 a4 Qc7 7 Be2 Nf6 8 O-O Be7 9 Be3 O-O 10 Qd2 d6 11 Nb3 Kh8 12 a5 Nd7 13 Na4 Bd8 14 Nb6 Nxb6 15 axb6 Qb8 16 Rfd1 Be7 17 c4 Nd8 18 c5 dxc5 19 Bxc5 Nc6 20 Bxe7 Nxe7 21 Qb4 Ng6 22 Rd6 h6 23 Rad1 Kh7 24 g3 Ne7 25 Na5 f5 26 Rd8 Rxd8 27 Rxd8 Ng6 28 exf5 exf5 29 f4 Resigns.

Chernev reproduced his item on pages 192-193 of The Chess Companion (New York, 1968), without correcting his duplication of numbers at move 21.

Below is the game, played on 23 January 1927, as given with the winner’s notes on page 25 of Československý šach, February 1927:

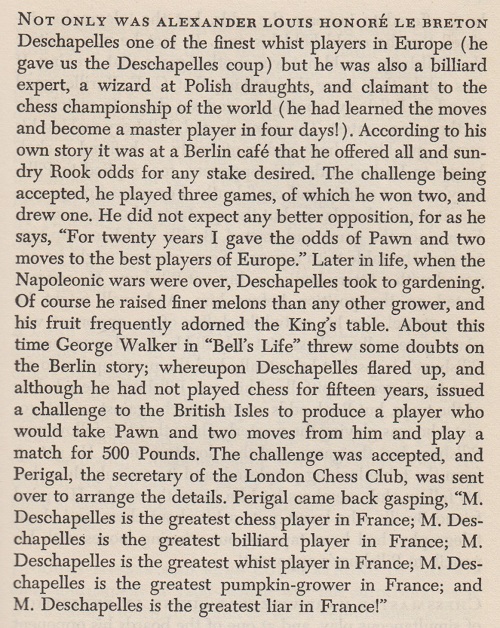

9995. Deschapelles

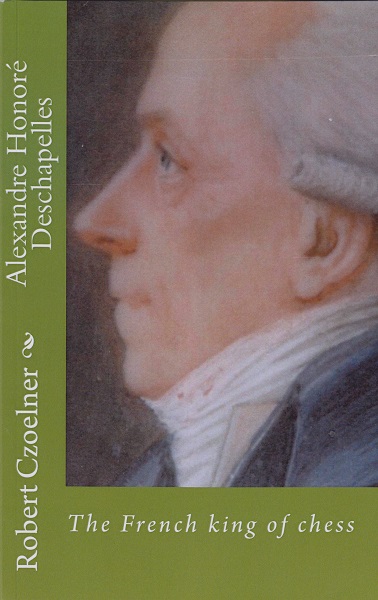

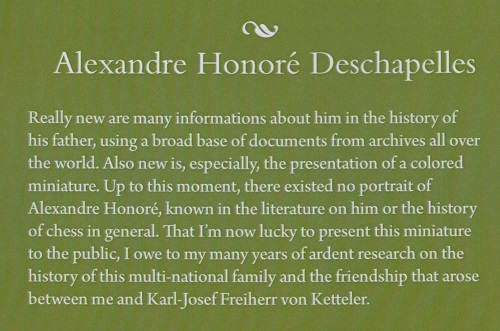

The warning about not judging a book by its cover is particularly relevant nowadays, because Internet sites (Amazon.com, for instance) are listing more and more volumes with a glossy outside and a trashy inside.

The final page of Alexandre Honoré Deschapelles. The French king of chess by Robert Czoelner states, ‘Printed in Poland by Amazon Fulfillment Poland Sp. z o.o., Wrocław’. The 112-page book is undated, and there is not even a title page. The text, in English, French and German, is spaced out in the dispiriting manner of on-demand/vanity press books, and in the Foreword (page 3) the author states that he is in Brazil and all his documentation is in Germany (‘This explains why the articles don’t cite many sources’). Whatever research material of value there may be is lost in the clutter, and to some extent the book can be judged by its back cover:

Page 28 gives, out of nowhere, a quote on which our present item will focus:

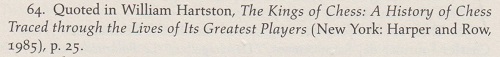

The matter frequently fills a paragraph or so in chess books. From page 41 of Crescendo of the Virtuoso by Paul Metzner (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1998):

The endnote reference 64 takes the reader to page 306 for this let-down:

The text in Hartston’s book:

‘Deschapelles might perhaps best be summarised in the words of George Périgal who, after interviewing the great man in Paris in 1836, returned home sighing: “M. Deschapelles is the greatest chess player in France; M. Deschapelles is the greatest whist player in France; M. Deschapelles is the greatest billiard player in France; M. Deschapelles is the greatest pumpkin-grower in France; and M. Deschapelles is the greatest liar in France.”’

If a sourceless citation were deemed sufficient, it might just as well be page 11 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

See too G.H. Diggle’s article on Deschapelles in the May 1979 Newsflash and on pages 46-47 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984). The conclusion:

‘And so we must leave him on a note of interrogation, as George Perigal did in 1836, when after interviewing the Frenchman in Paris he returned home gasping “M. Deschapelles is the greatest chessplayer in France; M. Deschapelles in the greatest whistplayer in France; M. Deschapelles is the greatest billiard player in France; M. Deschapelles is the greatest pumpkin-grower in France; and M. Deschapelles is the greatest liar in France.”’

Two far earlier versions are added, the first being from an article ‘Some Nineteenth-Century Chess Books and Chess Players’ by A.C. on pages 397-401 of the September 1907 BCM. This is on page 400:

Page 53 of The Exploits and Triumphs, in Europe, of Paul Morphy, The Chess Champion by F.M. Edge (New York, 1859):

The match negotiations in which George Perigal was involved are related at length in Copy of the Correspondence Between the French and English Committees Relative to a Proposed Match Between Monsieur Deschapelles and Any Player in England (London, 1836). The book can be read on-line.

In the ‘liar’ accounts shown above, there is evidently much copying (e.g. three occurrences of the word ‘gasping’ in connection with Perigal), but what is the exact origin of the story?

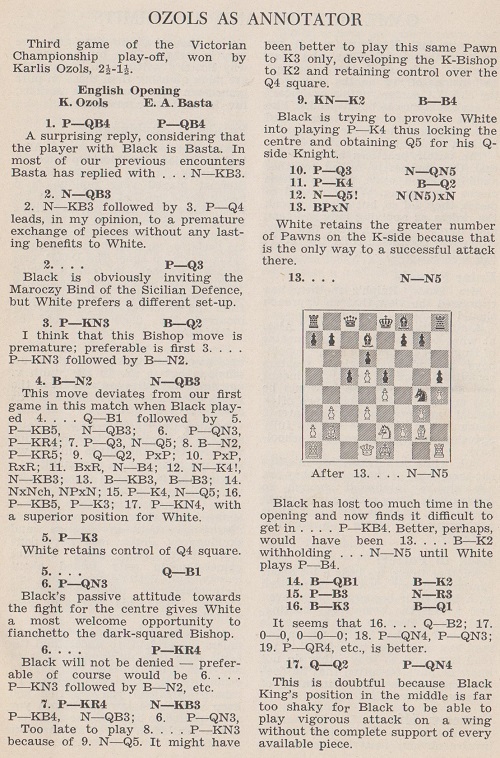

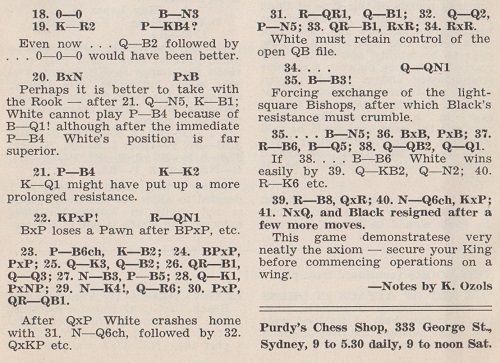

9996. Ozols v Basta

A rare specimen of a game annotated by Karlis Ozols is on pages 66-67 of Chess World, March-April 1967:

1 c4 c5 2 Nc3 d6 3 g3 Bd7 4 Bg2 Nc6 5 e3 Qc8 6 b3 h5 7 h4 Nf6 8 Bb2 e5 9 Nge2 Bf5 10 d3 Nb4 11 e4 Bd7 12 Nd5 Nbxd5 13 cxd5 Ng4 14 Bc1 Be7 15 f3 Nh6 16 Be3 Bd8 17 Qd2 b5 18 O-O Bb6 19 Kh2 f5 20 Bxh6 gxh6 21 f4 Ke7

22 exf5 Rb8 23 f6+ Kf7 24 fxe5 dxe5 25 Qe3 Qc7 26 Rac1 Qd6 27 Nc3 c4 28 Qe1 cxb3 29 Ne4 Qa3 30 axb3 Rbc8 31 Ra1 Qf8 32 Qd2 b4 33 Rac1 Rxc1 34 Rxc1 Qb8 35 Bf3 Bg4 36 Bxg4 hxg4 37 Rc6 Bd4 38 Qc2 Qd8 39 Rc8 Qxc8 40 Nd6+ Kxf6 41 Nxc8 and wins.

9997. Photographic archives (19)

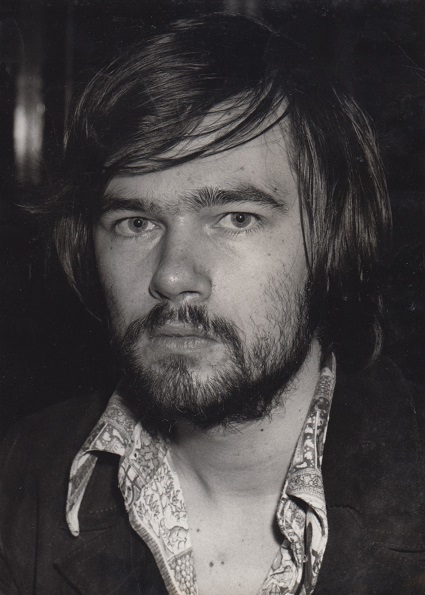

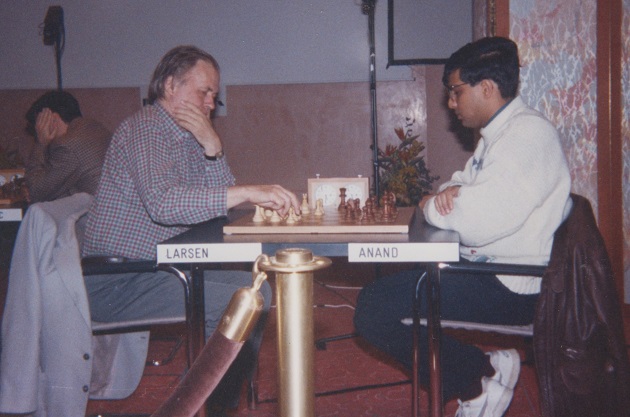

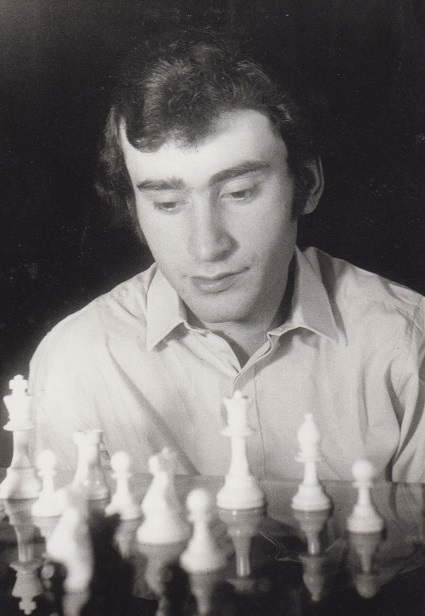

A further set of photographs from our collection:

Walter Browne

Bent Larsen and Viswanathan Anand, Monaco, 1992

Henrique Mecking

Nigel Short and Anatoly

Karpov, Linares, 1992

Michael Stean

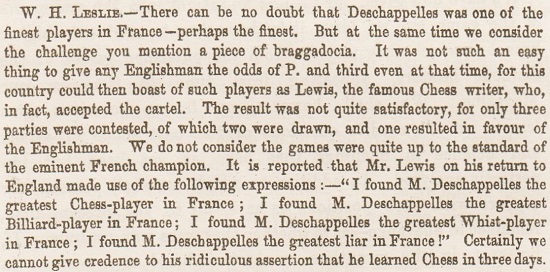

9998. Deschapelles (C.N. 9995)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) reports that he has found no publication of the Deschapelles story which predates F.M. Edge’s of 1859. He adds an item from page 96 of the Chess Player’s Magazine, 1863 (‘Answers to Correspondents’) which refers to an earlier set of negotiations for a match involving Deschapelles and ascribes the ‘liar’ quote not to George Perigal but to William Lewis:

9999. The simplest and clearest book for beginners

With regard to the absolute basics of chess, which is the simplest and clearest book ever written?

A strong candidate is The Easiest Way to Learn Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1960), published in the United Kingdom as The Modern Fundamentals of Chess (London, 1961).

10000. Marcel Duchamp

From Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA):

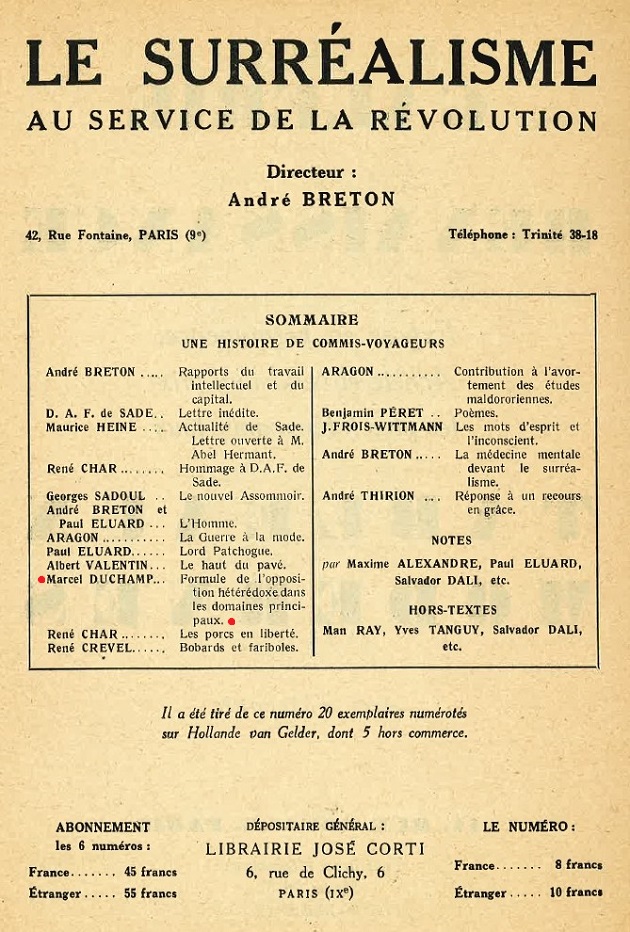

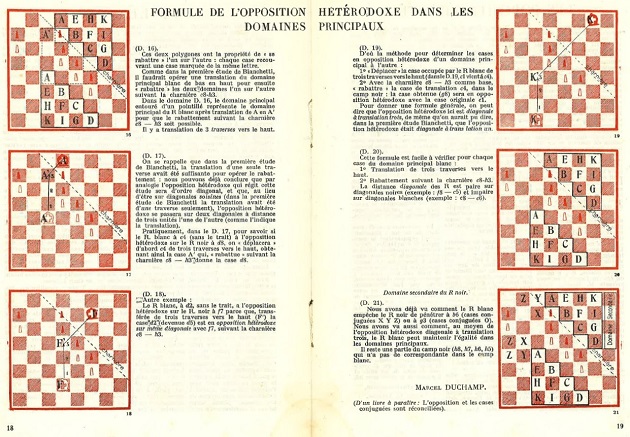

‘André Breton’s Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution, number 2, published in October 1930, included an item by Marcel Duchamp entitled “Formule de l’opposition hétérodoxe dans les domaines principaux” (pages 18-19). It consisted of six chess diagrams with accompanying text which prefigured pages 80-81 of the book which he wrote in collaboration with Vitaly Halberstadt, L’opposition et les cases conjuguées sont réconciliées (Brussels, 1932).

Parenthetically labeled “D’un livre à paraître: L’opposition et les cases conjuguées sont réconciliées”, Duchamp’s article may be viewed as an attempt to promote the project. In a letter to Katherine Dreier dated 18 December 1930 and published on pages 171-172 of Affectionately, Marcel: The Selected Correspondence of Marcel Duchamp edited by Francis M. Naumann and Hector Obalk (Ghent, 2000) Duchamp mentioned his continuing efforts to find a publisher for his book.

It nonetheless remains unclear why this fragment of a complex chess study appeared in a publication devoted to art and politics, and particularly considering Breton’s comment in Second Manifeste du surréalisme (Paris, 1930) regarding Duchamp’s career:

“Libre n’était pas à Duchamp d’abandonner la partie qu’il jouait aux environs de la guerre pour une partie d’échecs [Breton’s emphasis] interminable qui donne peut-être une idée curieuse d’une intelligence répugnant à servir [Breton’s emphasis] mais aussi – toujours cet exécrable Harrar – paraissant lourdement affligée de scepticisme dans la mesure où elle refuse de dire pourquoi.” (Page 64.)

With his reference to “exécrable Harrar”, Breton compared Duchamp’s apparent abandonment of art for chess to Rimbaud giving up poetry to become a trader in Abyssinia, a comparison which suggests that Breton saw a clear disconnect between art and chess.

Duchamp did refer to chess as an artistic endeavor, however. One example is found on page 55 of Observations by Richard Avedon and Truman Capote (New York, 1959) where Duchamp, quoted by Capote, commented on L’opposition et les cases conjuguées sont réconciliées:

“It has to do with blocked pawns, when your only means of winning is by moves of kings. This happens only once in a thousand times. And why, ... why isn’t my chess playing an art activity? A chess game is very plastic. You construct it. It’s mechanical sculpture and with chess one creates beautiful problems and that beauty is made with the head and hands.”

In an address made in 1952 at a banquet of the New York State Chess Association, quoted on page 72 of the third revised edition of The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp by Arturo Schwarz (New York, 2000), Duchamp discussed the relationship between chess and art in some detail, concluding with the observation that “while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists”.

It is also noteworthy that Duchamp’s piece in Breton’s publication included an ending by Rinaldo Bianchetti. As discussed in C.N. 6004, Duchamp and Halberstadt were accused of plagiarizing Bianchetti’s Contributo alla teoria dei finali di soli pedoni (Florence, 1925).’

10001.

Karpov on chess writers (C.N. 9980)

C.N. 9980 quoted from pages 73-74 of From Baguio to Merano by A. Karpov and V. Baturinsky (Oxford, 1986). The Russian book with Karpov’s observations was В далеком Багио (Moscow, 1981), and the passage in question is shown below, from pages 155-156:

10002. Ozols v Hanks

A game played on the same day as J. Purdy v F. Campomanes (C.N. 9986):

Karlis Ozols – John Nugent Hanks

Melbourne Olympic Tourney, 3 January 1957

Dutch Defence

1 d4 f5 2 Bg5 Nf6 3 Nd2 e6 4 e4 fxe4 5 Nxe4 Be7 6 Ng3 O-O 7 Bd3 Qe8 8 h4 Nc6 9 c3 e5 10 d5 Nd8 11 Qc2 h6 12 O-O-O Nf7 13 Bg6 Qd8

14 Nf5 d6 15 Nf3 Nh8 16 Bh7+ Kf7

17 Nxh6+ gxh6 18 Bxh6 Bg4 19 Ng5+ Ke8 20 Bxf8 Bxd1 21 Bg6+ Kxf8 22 Ne6+ Kg8 23 Rxd1 Qd7 24 Bf5 e4 25 g4 c6 26 g5 cxd5 27 gxf6 Bxf6 28 Rxd5 Bxh4 29 Qxe4 Bf6 30 Kb1 Qc6 31 Nd4 Bxd4 32 Be6+ Kf8 33 Rf5+ Bf6 34 Rxf6+ Ke7 35 Qh4 Rf8 36 Rf7+ Kxe6 37 Qf6+ Kd5 38 Rxf8 Resigns.

Source: Chess World, April 1957, pages 95-96.

There were annotations by Robert Pikler, who concluded:

‘An excellent game by Ozols, played with dash and abandon.’

A lengthy note at move 14 included the following remark:

‘“A move like Mary Stuart – beautiful but unfortunate” the late Dr Tartakower was wont to say.’

As discussed in previous C.N. items (see the Factfinder), the phrase has been widely attributed to Janowsky (from 1898 onwards, i.e. well before Tartakower’s time). Usually the queen referred to is Mary Stuart (Mary Queen of Scots), but we should like to add some references to Marie Antoinette’s name in this context.

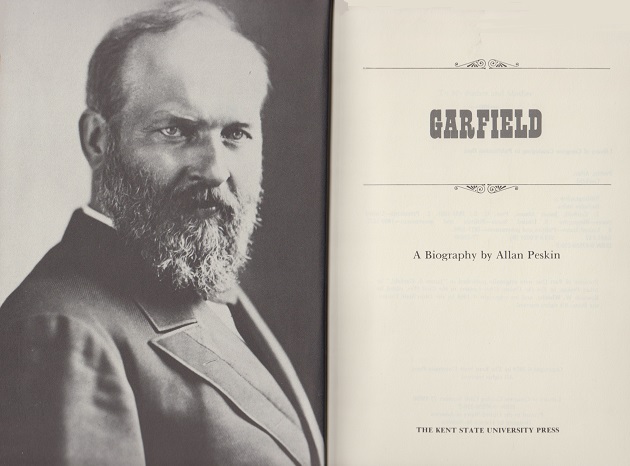

10003. President James A. Garfield

Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) writes:

‘The book Garfield A Biography by Allan Peskin (Kent, 1978) has interesting material on the twentieth US President, James A. Garfield. Page 57 observes that when heading a college named the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute in around 1858, Garfield tried to start a chess league but that ...:

“The local bluenoses protested his endorsement of a vain amusement and forced him to cancel plans for a chess league with neighboring colleges.”

On page 46 it is noted that Garfield graduated from Williams College in 1856. That is the same college which, in 1859, played the first-known American intercollegiate chess match, versus Amherst College, as part of a combined event with the first-known intercollegiate baseball game. If Garfield had had his way, he might have anticipated his alma mater in this regard.

Page 623 says:

“Garfield’s fondness for the game [chess] led him to recommend it to his students as an antidote for overly abstract study. “Frequently lay aside Emerson and study Morphy”, he suggested.’

Pages 153 and 273 have a description of his games with Salmon P. Chase, who “revealed a passion for chess that matched Garfield's own” and who served as Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court among other high offices. On page 273 it is reported that during his chess games with Chase, Garfield often discussed his desire to quit politics but that Chase would persuade him to continue.’

10004. Kasparov v Korchnoi, Pasadena, 1983

From Bruce Monson (Colorado Springs, CO, USA):

‘Even though Kasparov did not show up for the start of game one in Pasadena in 1983, Korchnoi was there and actually made a move, 1 d4. Kasparov was forfeited, of course, but ultimately this did not count.

I have not seen any photographs of Korchnoi sitting at the board across from Kasparov’s empty chair. Do you know of any?’

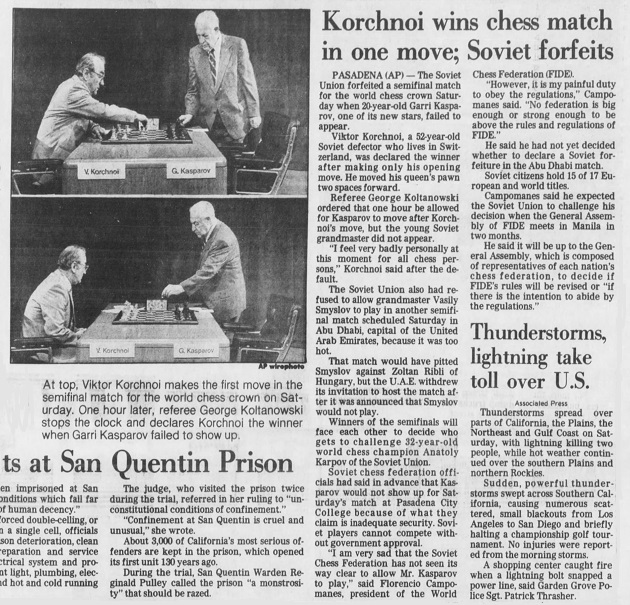

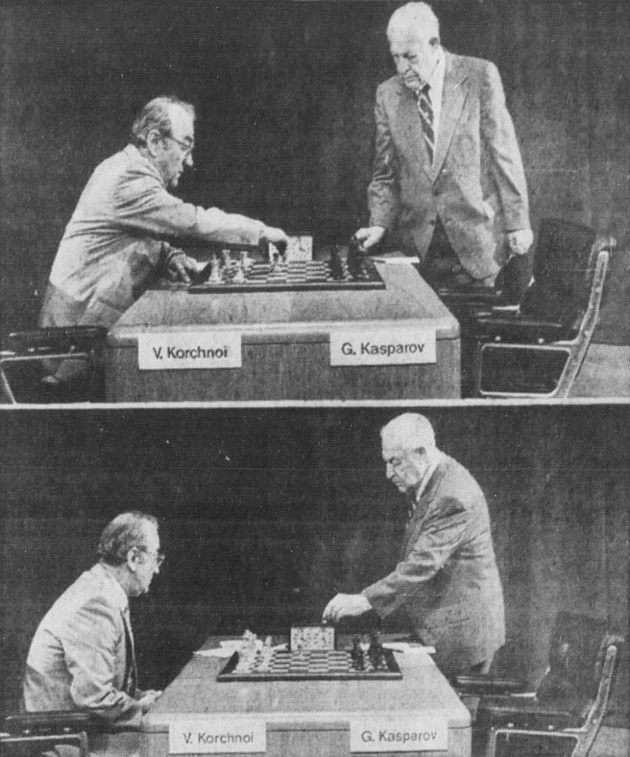

The Candidates’ Semi-Final match between Kasparov and Korchnoi was due to begin in Pasadena on 6 August 1983. Below is a report on page A2 of the following day’s edition of the San Bernardino County Sun:

10005. My System and piracy

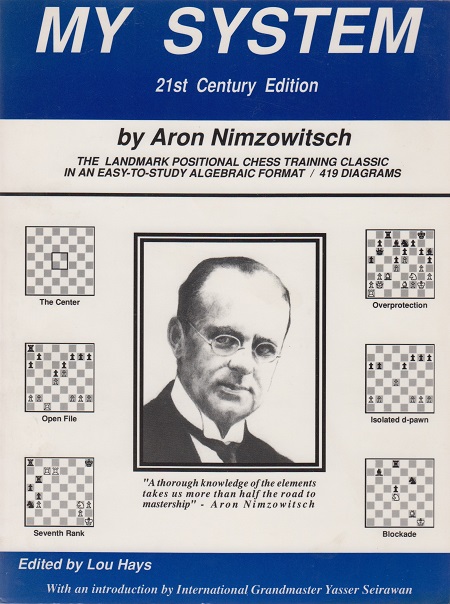

My System, Philip Hereford’s translation of Nimzowitsch’s best-known book, Mein System, was published by G. Bell and Sons, Ltd., London in 1929 and by Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York in 1930. In 1991, Hays Publishing, Inc, Dallas issued a ‘21st Century Edition’ which, the title page specified, was ‘edited and converted to algebraic notation by Lou Hays’:

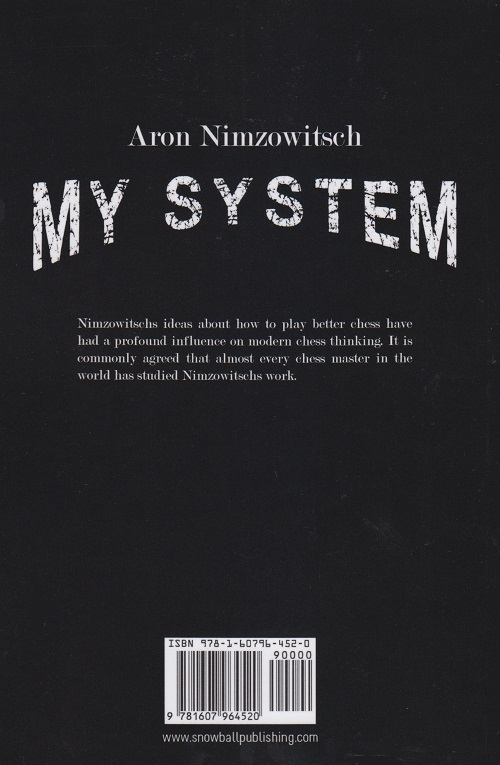

We have now come across another edition of the Hays volume:

Although the body of the work is identical to the 1991 book, all mention of Lou Hays and Hays Publishing, Inc. has been deleted, as has Yasser Seirawan’s 2½-page introduction.

At the end of the book there is a full-page advertisement, under the heading ‘Recommended Readings [sic]’, for The Art of Checkmate by Georges Renaud [sic], but we have found no corroboration of the claim that it is ‘available at www.snowballpublishing.com’.

We do, though, have one other Snowball Publishing volume, also dated 2012: Zurich International Chess Tournament 1953 by David Bronstein:

The name of the translator, Jim Marfia, has been retained on the title page, but the book is merely a low-quality reprint of what Dover Publications, Inc., New York brought out in 1979 (front cover below), with all reference to Dover removed.

10006. Frederick Orrett

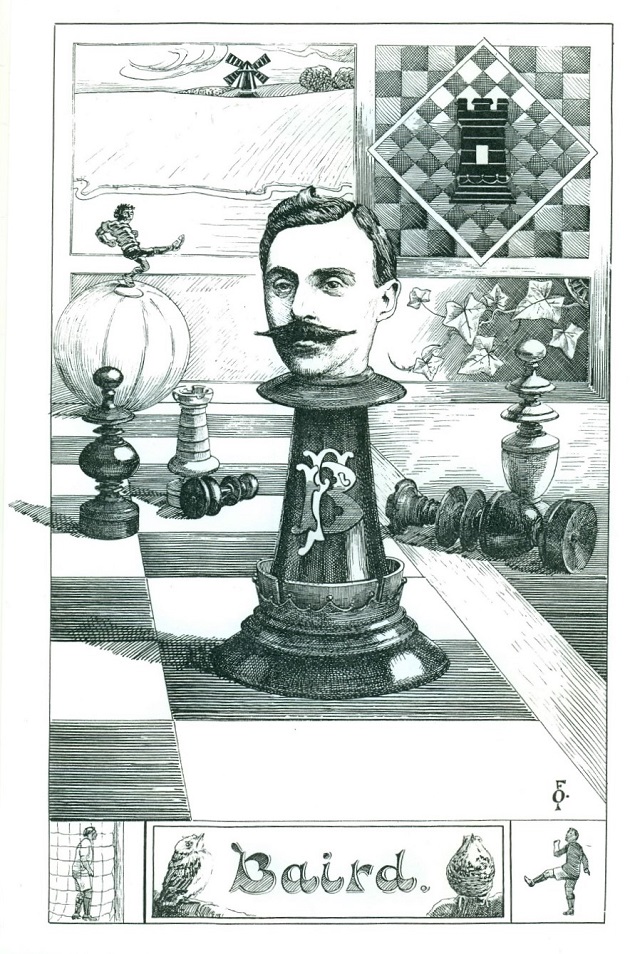

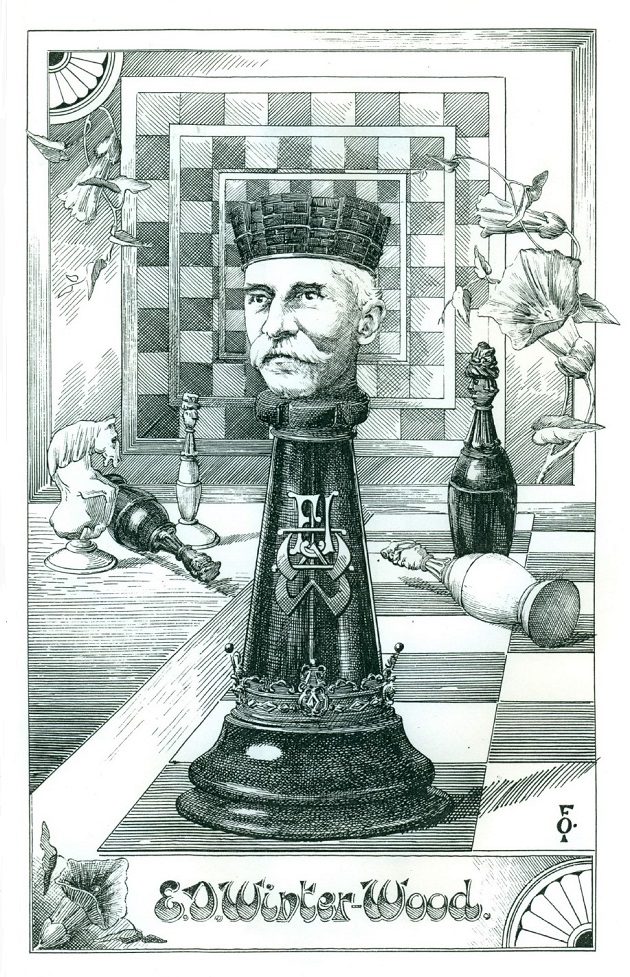

The series of portraits by Frederick Orrett forwarded to us by Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) continues with Frederick Baird, Albert Waterhouse and Edward John Winter-Wood:

| First column | << previous | Archives [143] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.