Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [144] | next >> | Current column |

10007. Photographic archives (20)

A further set of photographs from our collection:

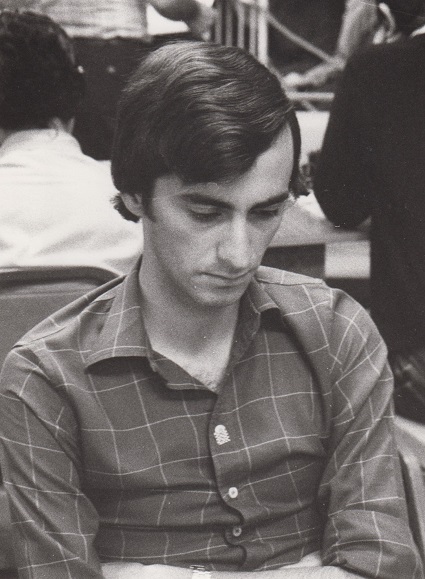

Juan Manuel Bellón

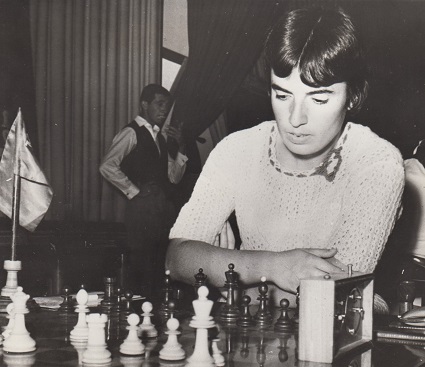

Nona Gaprindashvili

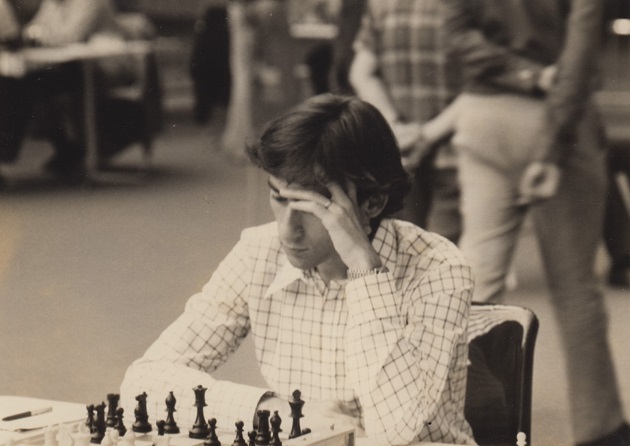

Svetozar Gligorić and Miguel Quinteros (Interzonal tournament, Leningrad, 1973)

William Hartston

10008. Quiz question

Which brilliancy played in 1956 did C.J.S. Purdy annotate under the title ‘Game of the Century? Yes and No’?

10009. Au voleur... (Philippe Dornbusch)

Mr Philippe Dornbusch has announced his candidacy for the

post of President of the Fédération Française des

Echecs/French Chess Federation (election to be held in

December 2016), and his campaign includes a seven-point

plan to improve the Federation’s website.

This is the same Philippe Dornbusch whose own website includes a notice ‘© Chess & Strategy - Reproduction et diffusion interdites’ yet, as shown in Copying, makes indiscriminate use of other people’s material, without acknowledgement or permission. Of late, his site has lifted images from Chess Notes which depict, for instance, Fischer, Spassky and Karpov, and the latest case is the fine photograph of Michael Stean which we own (given on 21 June 2016 in C.N. 9997).

The section on Mr Dornbusch in our above-mentioned

feature article began with the observation, ‘Copying

usually goes hand-in-hand with incompetence’, and

demonstrated how he had misappropriated from C.N. 8894 a

photograph of Edgar Pennell, chopped off the caption (from

CHESS) and misidentified Pennell as Koltanowski.

That is not an isolated case. In another

article (May 2016) Mr Dornbusch gave a photograph of

Reshevsky but stated that it was Capablanca, even though

the facts are set out in our article Chess: Mistaken

Identity, where this version was presented:

Reshevsky, not Capablanca

Unaware that he should have been writing about Reshevsky, Philippe Dornbusch added a biography of Capablanca (over 430 words). The entire text was lifted, without any attribution, from the French-language Wikipedia entry on Capablanca.

Addition on 4 July 2016: Following the appearance of the above item, Philippe Dornbusch replaced his quiz-question photographs of Pennell and Reshevsky by pictures of Koltanowski and Capablanca which, in accordance with his customary malpractice, he simply lifted from other websites without acknowledgement. For further details, see Copying.

10010. Wikipedia

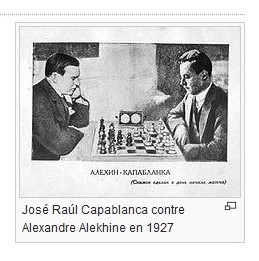

The French edition of Wikipedia is one of many language versions which give (on both masters’ pages) the fake photograph of Alekhine and Capablanca:

10011. From Herman Steiner’s archives

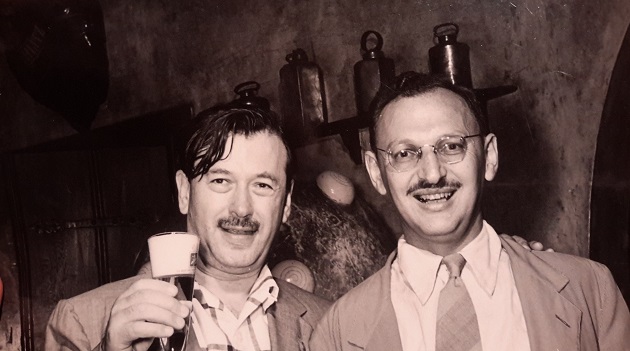

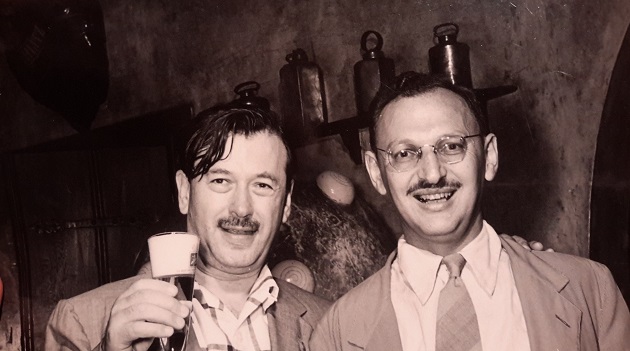

Bruce Monson (Colorado Springs, CO, USA) asks for information about this photograph, which comes from the archives of Herman Steiner (left):

10012. Rook endings (C.N.s 5498, 5585, 5726 & 5822)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) notes that page 108 of El Ajedrez Americano, April 1931 ascribed to Tartakower the following remark in the transcript of a lecture in Buenos Aires on 6 April 1931:

‘Al contrario que en los finales de peones solos contra peones, en el final de torres y peones contra torre y peones, la ventaja gana casi siempre.’

Our correspondent adds that this assertion (that a material advantage will nearly always win in rook endings, but not in pawn endings) was the opposite of what Tartakower had said. He asked for a correction to be published, and on page 130 of the May 1932 [sic] issue Roberto Grau wrote concerning Tartakower:

‘Afirmó que en el final de torre y peones contra torre y peones pasa todo lo contrario que en el final de peones solos, ya que “la pequeña ventaja material se neutraliza casi siempre”. (En el artículo anterior se deslizó un error tipográfico y se dijo todo lo contrario. El Dr Tartakower nos pidió oportunamente la rectificación que ahora publicamos.)’

10013. Zukertort’s monodrama

A paragraph typical of W.N. Potter’s prose style is on page 257 of the City of London Chess Magazine, October 1875:

‘The September monodrama at the City Club was performed by Herr Zukertort. He came, saw – he did not take long in seeing – and conquered. The whole affair was over in less than three hours. There were 17 adjuncts, but they all went home weeping save Mr Blunt, who drew his game.’

10014. ‘I once heard a story’

Concerning How Many Moves Ahead?, page 39 of Winning Chess Tournaments by Robert M. Snyder (Lincoln, 2007) had another variation:

‘I once heard a story where a reporter asked the famous master Jose Capablanca, “How many moves do you see ahead?” He jokingly said, “Fifty!” The reporter, not knowing much about chess, wrote that down in his notes and then proceeded to ask another famous master, Richard Réti, the same question. Réti said, “One! But always the right one.” There is something to be learned from this: You only need to see as deep as necessary to establish the best move for the position.’

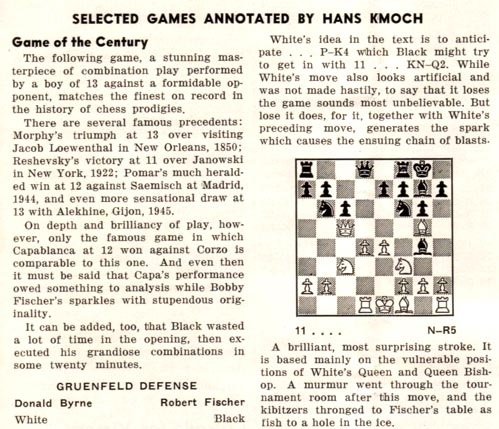

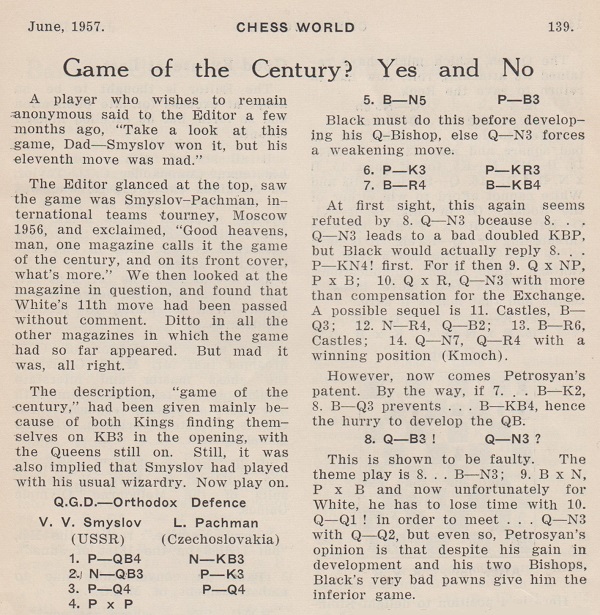

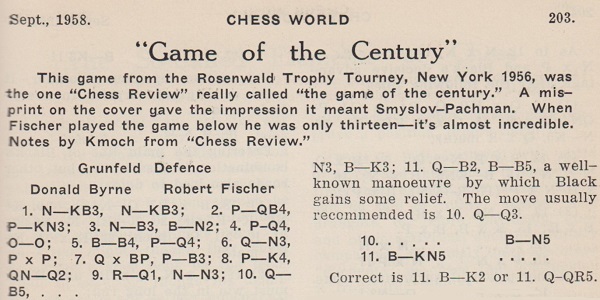

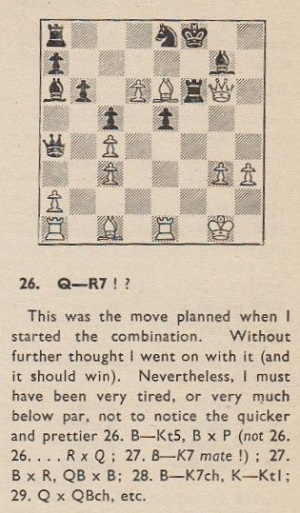

10015. The Game of the Century (C.N. 10008)

As a quiz question, C.N. 10008 asked which brilliancy played in 1956 was annotated by C.J.S. Purdy under the title ‘Game of the Century? Yes and No’.

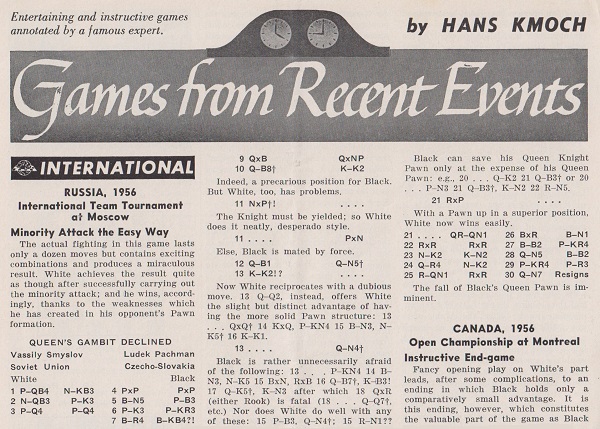

Noting that the phrase ‘Game of the Century’ was used in the context of prodigies’ performances, C.N. 3880 showed part of Hans Kmoch’s article about Byrne v Fischer, New York, 1956, from page 374 of Chess Review, December 1956:

To answer the quiz question it is therefore tempting to jump to the conclusion that it was the Byrne v Fischer encounter that Purdy described as ‘Game of the Century? Yes and No’, but the importance of not jumping to conclusions is the theme of the present item.

The game discussed by Purdy was Smyslov v Pachman, Moscow Olympiad, 1956: 1 c4 Nf6 2 Nc3 e6 3 d4 d5 4 cxd5 exd5 5 Bg5 c6 6 e3 h6 7 Bh4 Bf5 8 Qf3 Qb6 9 Qxf5 Qxb2 10 Qc8+ Ke7 11 Nxd5+ cxd5 12 Qc1 Qb4+ 13 Ke2 Qb5+ 14 Kf3 Qd7 15 Bxf6+ Kxf6 16 g3 Qf5+ 17 Kg2 Bd6 18 Qd1 g6 19 Bd3 Qe6 20 Rb1 Nc6 21 Rxb7 Rab8 22 Rxb8 Rxb8 23 Ne2 Kg7 24 Qa4 Ne7 25 Rb1 Rxb1 26 Bxb1 Bb8 27 Bc2 h5 28 Qb5 Bc7 29 h4 a6 30 Qb7 Resigns. From page 139 of the June 1957 issue of Chess World:

Purdy discussed the game in more detail, under the title ‘That “Mad” Move by Smyslov’, on page 221 of the October 1957 Chess World and on pages 240-241 of the November 1957 issue.

As shown above, the original (June 1957) article included this remark by Purdy about Smyslov v Pachman:

‘... one magazine calls it the game of the century, and on its front cover, what’s more.’

Another conclusion not to be jumped to is that Purdy never realized or corrected his mistake. A year later he reverted to the matter in Chess World:

The relevant material in the December 1956 Chess Review:

- Front cover: a photograph of Fischer and, to the left, the words ‘Game of the Century (See page 370)’, that page number being a misprint:

- Page 370: Smyslov v Pachman, annotated by Kmoch (without, of course, any ‘Game of the Century’ claim):

- Pages 374-375: Byrne v Fischer, annotated by Kmoch (with the term ‘Game of the Century’, as shown at the start of the present item).

10016. From Herman Steiner’s archives (C.N. 10011)

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada) identifies Herman Steiner’s companion as Max Pavey.

For purposes of comparison, see the photograph of Pavey on page 5 of Chess Life, 5 January 1955.

On page 4 of Chess Life, 20 September 1957 Montgomery Major wrote:

‘Death claimed Max Pavey on 4 September 1957 at the age of 39 after a long confinement in the Mt Sinai Hospital. Leukemia and coronary complications “with a suspicion of radium intoxication” were the causes ascribed for his untimely passing.

... Max Pavey was a chemist by profession and for several years had been manager of the Canadian Radium and Uranium Corp. Laboratory in Mt Kisco, NY. It is suggested that he might have been the victim of radioactivity, according to a statement from the State Labor Department of New York, which has brought court action against the Canadian Radium and Uranium Corp., alleging laxity in reprocessing and salvaging radium.’

Was the cause of Pavey’s death ever clarified?

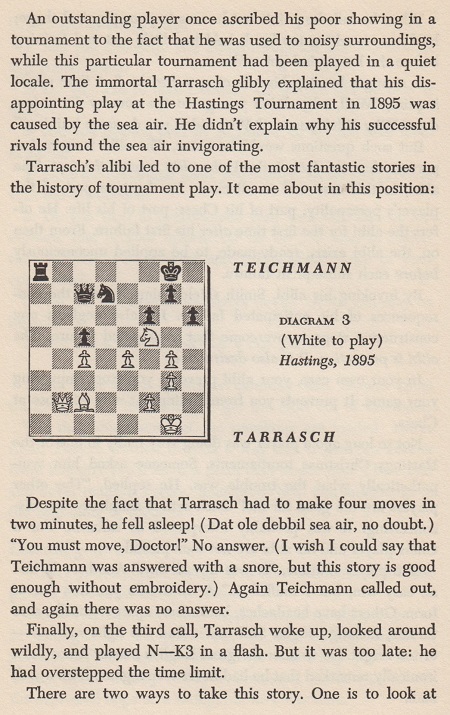

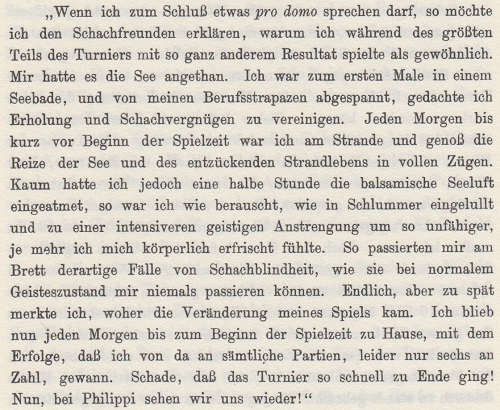

10017. Tarrasch, sea air and sleep

‘The immortal Tarrasch glibly explained that his disappointing play at the Hastings Tournament in 1895 was caused by the sea air.’

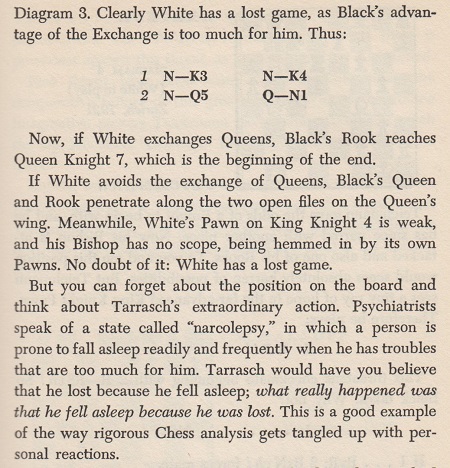

In C.N. 5724 a correspondent quoted that remark from page 10 of Why You Lose at Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1956 and London, 1957). Below is the full section (on pages 10-11), which includes ‘one of the most fantastic stories in the history of tournament play’:

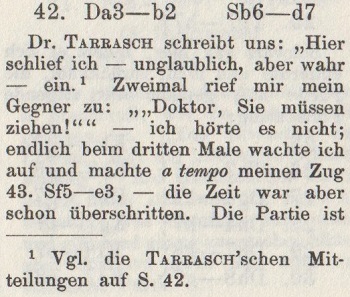

We note the following on pages 182-183 of Das internationale Schachturnier zu Hastings im August-September 1895 by E. Schallopp (Leipzig, 1896), at the end of the Tarrasch v Teichmann game:

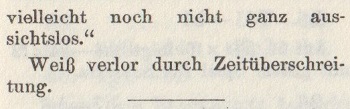

Tarrasch’s remarks on page 42, as referred to in the footnote:

10018. Bird, Gunsberg and Blackburne (C.N. 9527)

An uncreased copy of this photograph was published on page viii of Hastings 1895 by Colin Crouch and Kean Haines (Sheffield, 1995).

10019. ‘Suicide on the Chessboard’ (C.N. 9987)

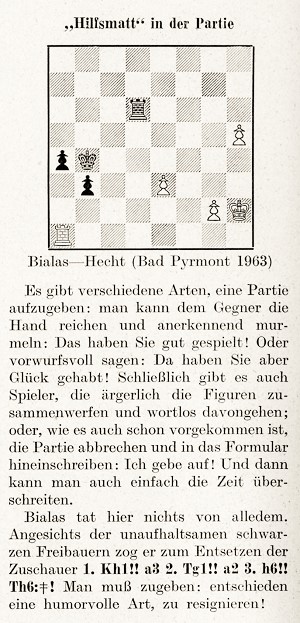

Regarding Bialas v Hecht, Bad Pyrmont, 1963, Michael Spiekermann (Menden, Germany) wonders whether the diagram given by Chernev and, as shown above, on page 12 of the January 1964 Deutsche Schachzeitung was correct, i.e. whether White’s rook stood on b1 rather than a1.

Our correspondent notes that various databases have 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nd2 Nc6 4 c3 e5 5 exd5 Qxd5 6 Ngf3 exd4 7 Bc4 Qf5 8 cxd4 Be6 9 O-O O-O-O 10 Qa4 Kb8 11 Bxe6 fxe6 12 Nc4 Bd6 13 Be3 Nge7 14 Nxd6 cxd6 15 Rac1 Nd5 16 Bg5 Rd7 17 b4 Nb6 18 Qa3 Qd5 19 Rfd1 h6 20 Bf4 Ka8 21 b5 Qxb5 22 Rb1 Nc4 23 Qd3 Qd5 24 a4 a6 25 Nd2 Nxd2 26 Rxd2 Rf8 27 Be3 Rc8 28 Rc2 Na7 29 Rxc8+ Nxc8 30 Rc1 Ne7 31 Qh7 Nf5 32 Qg8+ Ka7 33 Rc8 Nxe3 34 fxe3 Qb3 35 Kf2 Qa2+ 36 Kg3 Qd5 37 h4 Qe4 38 Rc3 Qg6+ 39 Kh3 Qf5+ 40 Kg3 Qg6+ 41 Kh3 h5 42 Kh2 Qg4 43 Kg1 e5 44 Rc8 Qd1+ 45 Kh2 Qxa4 46 dxe5 dxe5 47 Ra8+ Kb6 48 Qe6+ Qc6 49 Qb3+ Qb5 50 Qe6+ Kc7 51 Rh8 Qc6 52 Qe8 Rd2 53 Qe7+ Rd7 54 Qe8 Kb6 55 Rxh5 Rd2 56 Qxc6+ Kxc6 57 Rxe5 b5 58 Re6+ Rd6 59 Re7 b4 60 Rxg7 b3 61 Rf7 a5 62 Rf1 a4 63 Rb1 Kc5 64 h5 Kb4

65 Kh1 a3 66 Rg1 a2 67 h6 Rxh6 mate.

What is the most reliable primary source?

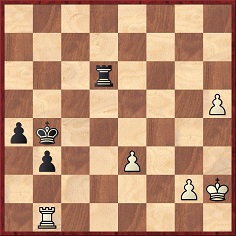

The game is not in Rochaden. Schacherinnerungen by Hans-Joachim Hecht (Berlin, 2015), a beautifully produced 429-page hardback.

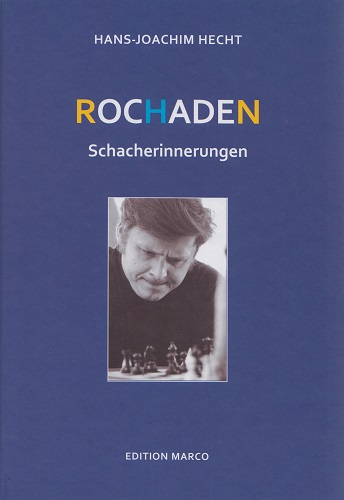

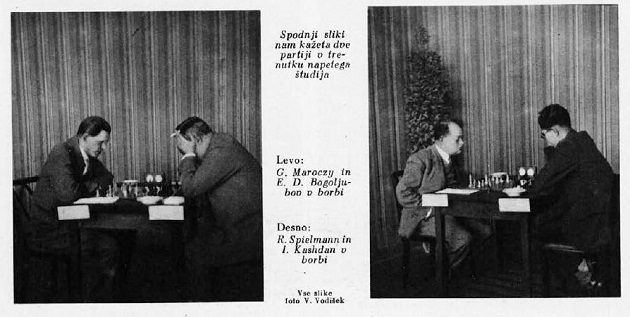

10020. Bled, 1931

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) sends a feature on Bled, 1931 from page 340 of the 10/1931 issue of Ilustracija:

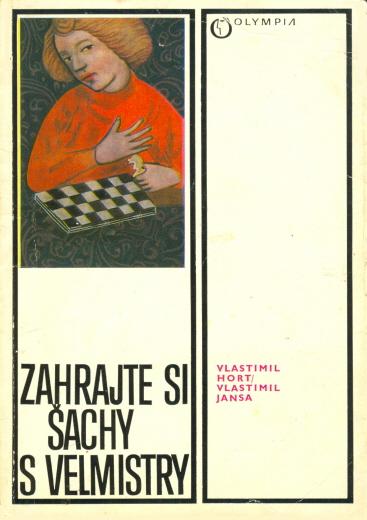

10021. Nimble expurgation (C.N. 6832)

C.N. 6832 (see too Patriotism, Nationalism, Jingoism and Racism in Chess) discussed Zahrajte si šachy s velmistry by V. Hort and V. Jansa (Prague, 1975) and quoted a remark by Lubomir Kavalek:

‘The publisher Olympia printed 18,000 copies and when it was done, some censors discovered my name attached to one of the games. They did something unbelievable: they cut out the page with my name, printed a new one without my name and glued it back in the book. They did it page by page, book by book – 18,000 times.’

Karel Mokrý (Prostějov, Czech Republic) draws our attention to an article of his which reports that two uncensored copies of the Hort/Jansa book are known to exist.

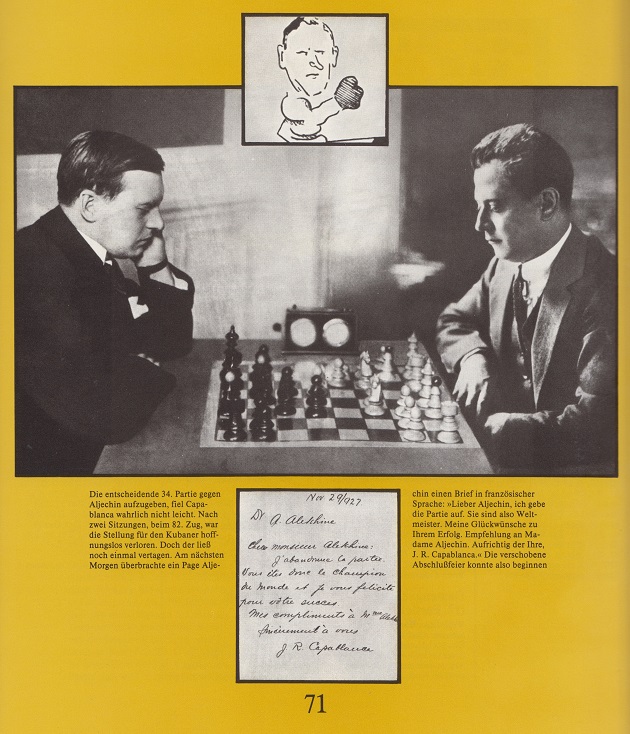

10022. Capablanca’s defeat by Alekhine

Richard Jones (Bologna, Italy) raises the question of whether Capablanca was a poor loser, and particularly in the immediate aftermath of his match defeat by Alekhine in 1927.

As shown on pages 202-206 of our monograph on the Cuban, his public statements about Alekhine’s victory were generous. The conclusion of the match was discussed on pages 348-350 and 521 of Miguel A. Sánchez’s 2015 book on Capablanca, but a properly documented account of what happened in Buenos Aires at the end of November 1927 remains to be written. With optimum use of source material, the chess historian must try to show what is certain, what is probable, what is unlikely and what is untrue, and at every stage the reader is entitled to ask, ‘Where did that come from?’ With erratic use of source material, Miguel A. Sánchez often makes do with a mixture of facts, assertion, imagination and speculation.

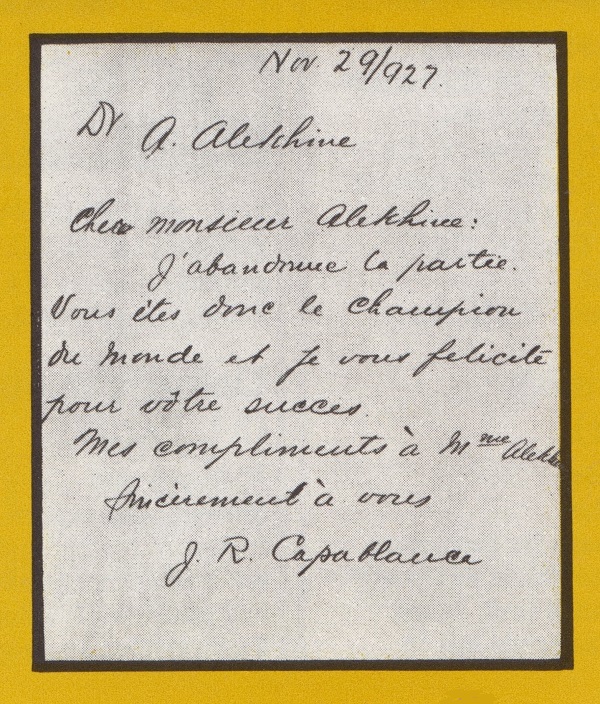

Concerning Capablanca’s letter of resignation of game 34, we do not know when the original first became public. One book which reproduced it (on a page chiefly comprising the fake Alekhine-Capablanca photograph) was Umkämpfte Krone by R. Stolze (East Berlin, 1986):

Correct French would have been desirable.

On page 521 of his book Sánchez characteristically referred to ...

‘... the text, originally written in French, although with some grammatical inaccuracies (probably because of Capablanca’s state of mind) and later fixed ...’

10023. Roll-call of world chess champions

On pages 6-7 of Como ser campeón en el ajedrez by Evgueni Leonov (Mexico City, 1985) the list of world champions includes Murphy, Ewe, Aleknine and Boltvinik. The last two names are Eddie Fischer and Boris Karpov.

10024. H.E. Atkins and mathematics

From page 69 of the December 1908 Chess Amateur:

‘Mr H.E. Atkins, MA, of Leicester, has been appointed principal of the Huddersfield College Municipal Secondary School for Boys. There were 171 candidates. Mr Atkins received his early education at Wyggeston School, Leicester, where he obtained a mathematical scholarship at Peterhouse, Cambridge, in 1890. After three years’ residence he graduated as ninth wrangler in the Mathematical Tripos. The following year he was placed in the first class in part two of the Tripos, and in 1895 was honourably mentioned for the Smith’s prizes. During the past six years he has held the post of mathematical master of the Wyggeston School, having previously been assistant master at King’s School, Canterbury, and Northampton County Secondary School.’

10025. Half

a minute per move

A surprising remark on page 13 of How to Improve Your Chess: Second Steps by I.A. Horowitz and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1952):

‘When a master gives a simultaneous exhibition against anywhere from 20 to 60 opponents, he has something like half a minute for each move he makes.’

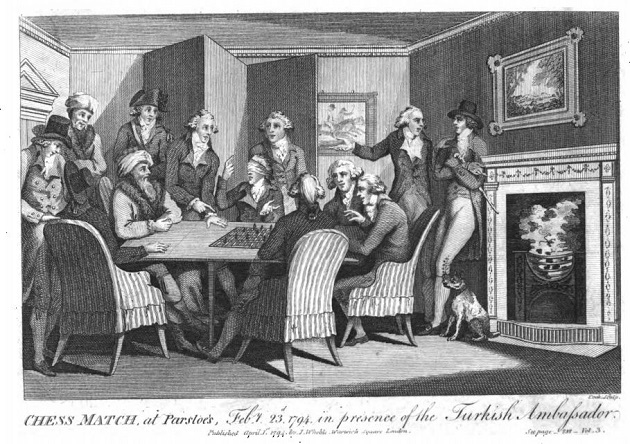

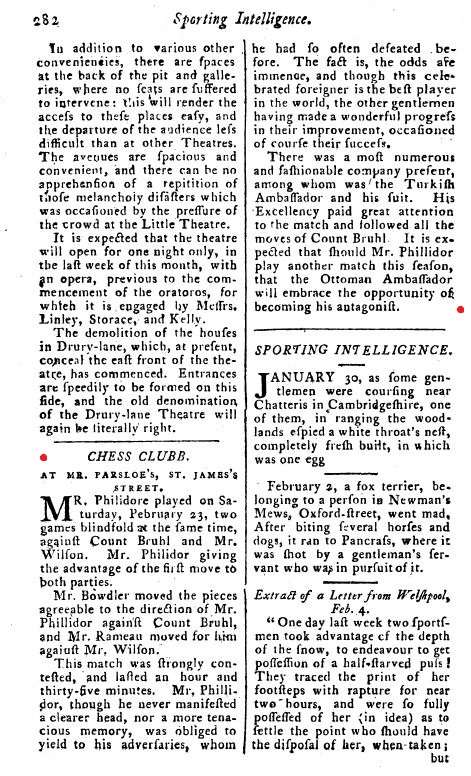

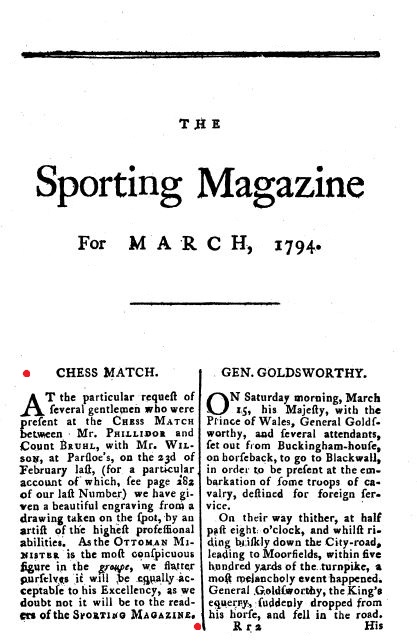

10026. Philidor engraving

Aaro Jalas (Espoo, Finland) asks for particulars about this famous picture of Philidor, and mentions, by way of example, how it is presented in two books:

- Page 17 of the Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games by David Levy and Kevin O’Connell (Oxford, 1981): ‘Philidor F.A.D. [blindfold simultaneous display], Brühl, J.M., Wilson J. London 23 ii 1794.’

- Page 97 of Philidor. Eine einzigartige Verbindung von Schach und Musik by Susanna Poldauf (Berlin, 2001): ‘Philidor beim Blindsimultan im Parsloe’s am 23. Februar 1794 in Anwesenheit des türkischen Botschafters.’

We add, firstly, that the picture is also on page 119 of A History of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1976) but with a caption placing it a decade earlier:

‘The acknowledged master of eighteenth-century chess – Philidor playing blindfold at Parsloe’s in London in the presence of the Turkish Ambassador on 23 February 1784.’

A similarly worded caption, also with ‘23 February 1784’, appeared on page 131 of Pocket Book of Chess by Raymond Keene (London, 1988). Page 23 of Blindfold Chess by Eliot Hearst and John Knott (Jefferson, 2009) had ‘in the 1780s’, and page 78 of The World of Chess by Anthony Saidy and Norman Lessing (New York, 1974) had ‘c. 1794’.

The correct date is 23 February 1794. The engraving was included at the start of volume three of the Sporting Magazine, which covered October 1793-March 1794:

Below are two passages from, respectively, page 282 of the February 1794 issue of the Sporting Magazine and page 297 of the March 1794 edition:

10027. Dolo Falk (C.N.s 4623 & 6341)

Tomasz Lissowski (Warsaw) has sent us page 3 of the 6/1903 edition of Das interessante Blatt:

10028. Reuben Fine and the world championship

On page 10 of Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship (New York, 1973) Reuben Fine wrote regarding Alekhine:

‘When World War II ended, in 1945, all the leading masters of that day, incensed by his behavior, objected to his participation in international tournaments. The Soviets broke the boycott by having Botvinnik challenge Alekhine to a match for the title in 1946. Actually this was illegal, since Keres and I had prior claims. But Keres, born in Estonia, was a Soviet citizen, while I was no longer so interested.’

From pages 224 of the ‘revised and expanded edition’ of The World’s Great Chess Games by Fine (New York, 1976):

‘Legally there were various possibilities. Euwe might have reclaimed the title, as the last official champion before Alekhine. Or Keres and Fine could have been declared co-champions on the basis of their joint victory in the AVRO tournament. Or Euwe, Fine and Reshevsky might have played a three-cornered tournament to decide the championship. Or the free world might have chosen a champion, and the communist world been left to choose its own; then the two could have met for the world championship.’

On the next page Fine wrote with respect to AVRO, 1938:

‘As indicated before, on the basis of this victory and in light of the circumstances of international chess in the war period, Keres and I should have been declared co-champions for the period 1946-48, between the death of Alekhine and the 1948 tournament.’

Finally, a comment by Fine on page 151 of Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958):

‘Keres and I tied for first in the AVRO tournament; he was declared winner by the tie-breaking Sonnenborn-Berger [sic] system. Alekhine dodged a match in his usual skillful manner. Then the war intervened and all official chess activity stopped.’

There is a frequent lack of rigour in claims that Alekhine ‘dodged’ opponents, and it is unimpressive to find C.J.S. Purdy writing the following in a review of Lessons from My Games on pages 146-147 of Chess World, September-October 1967:

‘Reuben Fine became one of the world’s greatest players. At the time when his claims to play a match for the world title were unanswerable, he did not get to play a match because Alekhine, once he had regained his title from Euwe, did everything possible to evade a match.’

As regards possible challenges to Alekhine after AVRO, 1938, an observation on page 215 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004) is noteworthy:

‘Fine seems not to have made any effort at all ...’

Related feature articles:

- World Championship Disorder

- The World Chess Championship by Paul Keres

- Interregnum

- Reuben Fine, Chess and Psychology.

10029. Paulsen v Morphy (C.N. 7120)

After giving the finish of Morphy’s celebrated win at New York, 1857 against Louis Paulsen (17...Qxf3), Fred Reinfeld wrote on page 156 of Great Moments in Chess (New York, 1963):

‘Beautiful, isn’t it? Géza Maróczy, the author of a definitive book of Morphy’s games, has this closing comment: “Morphy played the whole game faultlessly, powerfully, and with youthful verve.”Is this the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth? Not by a long shot.’

Reinfeld then discussed the play from move 17 onwards, examining the quicker wins missed by Morphy.

Contrary to the impression thereby created, such

improvements had also been reported in Maróczy’s book Paul

Morphy (Leipzig, 1909 and Berlin and Leipzig, 1925),

on pages 45-46 and 30-31 respectively. See too pages 30-31

of the English-language edition by Robert Sherwood

(Yorklyn, 2012).

It is curious that despite analysing Morphy’s inferior handling of the conclusion, Maróczy did indeed write that Morphy had played the game faultlessly, as quoted by Reinfeld above. Both editions of Maróczy’s book stated:

‘Morphy spielte die ganze Partie tadellos, durchwegs kräftig und mit jugendlicher Verve.’

Conscientious annotators naturally mention the faster wins missed by Morphy in the Paulsen game. On pages 24-26 of Duels of the Mind (London, 1991) Raymond Keene noted none of them.

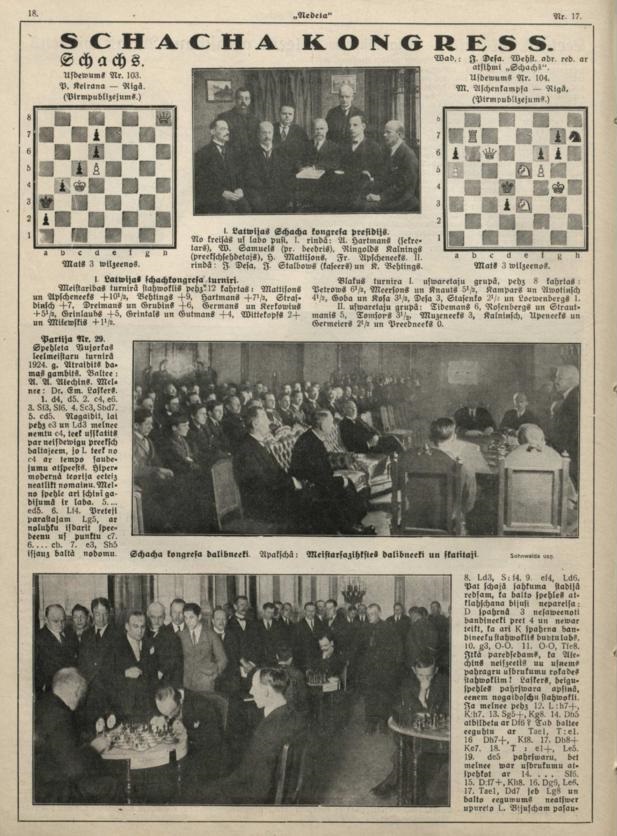

10030. Nedēļa

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) sends two items from the Latvian magazine Nedēļa:

23 April 1924, page 18

3 April 1925, page 13.

10031. Hypermodern players

‘It seems only a few years ago that the Hypermodern School, headed by Alekhine, Réti, Nimzowitsch, Bogoljubow and Breyer, infused a new vitality and profundity into the then extant chess theories.’

Source: Chess Strategy and Tactics by F. Reinfeld and I. Chernev (New York, 1933), page 96.

The omission of Tartakower may be considered a simple oubli. Regarding Bogoljubow, see Hypermodern Chess.

10032. Tournament in 1935-36 with 700,000 participants (C.N. 8926)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) refers to page 21 of Match radial internacional de ajedrez USA vs USSR by Arnoldo Ellerman (Buenos Aires, 1945). It quoted a review of the match by Mikhail Botvinnik in Izvestia which included this observation:

‘... sería suficiente mencionar que aproximadamente 700.000 jugadores participaron en el Campeonato “Trade Union” de 1937/38.’

10033. Allowing mate

After 48...Re5-c5, White resigned

The winner’s annotations to this game (B.Y. Mills v C.J.S. Purdy in round three of the Australian Championship, Adelaide, 1946-47) are on pages 292-294 of C.J.S. Purdy: His Life, His Games and His Writings by J. Hammond and R. Jamieson (Melbourne, 1982), with the following remark after 48...Rc5:

‘White can save his position only by allowing mate.’

See too pages 250-251 of the algebraic edition, The Search for Chess Perfection (Davenport, 1997).

When Purdy’s notes originally appeared on pages 115-116 of Chess World, 1 May 1947 the comment was:

‘White can save his pieces only by allowing mate.’

The full score of what Purdy described as ‘his best game of the tourney’ (Chess World, 1 February 1947, page 28), played on 28 December 1946: 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e3 O-O 5 Bd3 c5 6 Ne2 d5 7 a3 cxd4 8 exd4 dxc4 9 Bxc4 Be7 10 O-O Nbd7 11 Bg5 h6 12 Bh4 Nb6 13 Ba2 Bd7 14 Qd3 Bc6 15 Rad1 Nbd5 16 Bb1 Re8 17 Nxd5 Qxd5 18 Nf4 Qb5 19 Bxf6 Qxd3 20 Nxd3 Bxf6 21 Ne5 Ba4 22 Rd2 Red8 23 Re1 Rac8 24 f4 Bxe5 25 fxe5 Rc4 26 b3 Bxb3 27 Rb2 Rc3 28 Be4 b6 29 Rd2 Bd5 30 Rd3 Rxd3 31 Bxd3 Rc8 32 Re3 g6 33 Be2 Rc2 34 Kf1 Rd2 35 Rc3 Rxd4 36 Rc8+ Kg7 37 Rc7 a5 38 Bb5 Re4 39 Be8 Kf8 40 Bb5 Rxe5 41 a4 Rf5+ 42 Kg1 e5 43 Rc8+ Kg7 44 Rd8 e4 45 g4 Re5 46 Rd6 e3 47 Kf1 Bf3 48 Rxb6 Rc5 49 White resigns.

10034. Bishops of opposite colour

In the second round (27 December 1946) of the Adelaide tournament discussed in the previous item, ‘Purdy, after wriggling out of a loss against Brose, won after being two pawns down with bishops on opposite colours’ (Chess World, 1 February 1947).

Although the 71-move game is in databases, we have yet to trace it in a newspaper or magazine of the time. It was the subject of a brief report under the headline ‘Aust. Chess Sensation’ on page 7 of the Sydney Sun, 28 December 1946:

‘Sensation developed in the second round of the Australian chess championship when Purdy (NSW) made an oversight against South Australian champion Brose, and appeared certain to lose. Brose finally lost the game, in which loss had seemed impossible.’

10035. Seeing ahead

C.N. 9074 (see too ‘How Many Moves Ahead?’) showed an article by Vera Menchik on page 8 of the Daily Mail, 5 August 1927 in which she wrote:

‘When, for instance, I am asked how many moves I think ahead, I must, if I am truthful, give the same answer as that of the celebrated Czechoslovakian player Richard Réti: “Not even one move.”’

On page 265 of the 1 December 1947 issue of Chess World C.J.S Purdy introduced an article by Lajos Steiner, ‘How Many Moves Can You See Ahead?’, as follows:

‘Here is an entertaining article by the Australian champion, dealing with a question that every chess expert is asked ad nauseam. When a reporter asked it of the late Vera Menchik, she replied, “Oh, about one”. When another reporter asked it of the late Richard Réti, his dramatic sense got the better of him and he replied, “As a rule, not a single one”. Lajos Steiner gives a less cryptic reply’.

In his article, published on pages 265-266, Steiner wrote:

‘How far ahead to see? It is a question that everyone can answer for himself at the proper time, if he tries to approach positions with an open, critical mind. And that is the most important thing in a game of chess. It is better if we do not waste any more space at this juncture, and rather look at two positions.’

The diagrams given by Steiner:

White has a move which wins immediately

White mates in 90 moves

After outlining the solution to the second position, Steiner wrote:

‘An interesting piece of work, but the 90 moves of it are not much more difficult to see than the single move of the previous example.’

Steiner mentioned only that the problem was by Béla Bakay of Budapest, and we shall welcome further particulars. It is not one of the Bakay compositions in Ungarische Schachproblemanthologie by György Bakcsi (Budapest, 1983).

A future C.N. item will revert to the mate-in-90 problem, but the present item focuses on the first position. The game (Gerald Abrahams v František Zíta, London, 14 June 1947) was played on the first day of a two-round match between Great Britain and Czechoslovakia. From page 212 of the July 1947 BCM:

‘Abrahams succeeded in engineering one of his typical slashing attacks which apparently was quite sound, for on the 26th move ... he actually had an immediate win by a sensational queen’s sacrifice, first indicated by Professor Penrose.’

The game [a lengthy win for Black] was annotated by Abrahams on pages 14-18 of The Czechs in Britain by W. Ritson Morry (Birmingham, 1947). From page 15:

Abrahams gave the position (‘The game can be finished quickly by B-Kt5!’), mentioning neither the players nor the occasion, on pages 70-71 of The Chess Mind (London, 1951), although that information was added on page 72 of the Penguin edition (Harmondsworth, 1960).

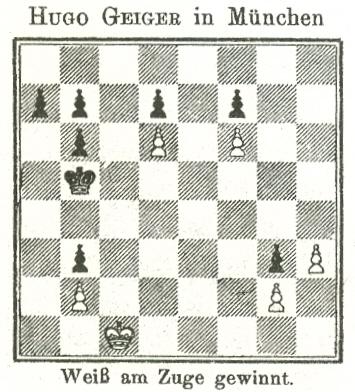

10036. Geiger composition (C.N. 7418)

Harold van der Heijden (Deventer, the Netherlands) answers the question in C.N. 7418 about who proposed the improvement (white king on b1, and not c1) in this study from page 38 of the February 1920 Deutsche Schachzeitung: Mikhail Zinar (Ukraine), on page 137 of a book co-written with Vladimir Archakov: Гармония Пешечного Этюда (Kiev, 1990).

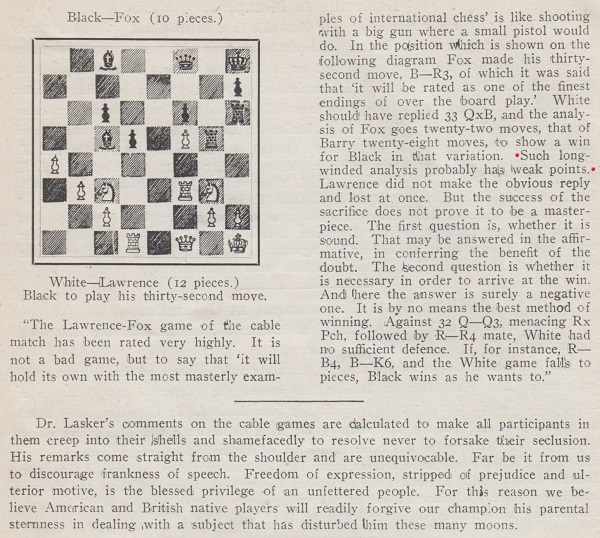

10037. Lawrence v Fox

C.N. 9260 quoted a remark by Julio Kaplan in an article on pages 364-366 of the July 1977 Chess Life & Review:

‘... as Lasker used to say: “Long analysis, wrong analysis”.’

From page 203 of Capablanca’s Best Chess Endings by Irving Chernev (Oxford, 1978):

‘... lengthy analysis may be suspect, as Dr Lasker once remarked.’

Citations from Lasker’s writings are still sought regarding these ‘used to’ and ‘once’ assertions.

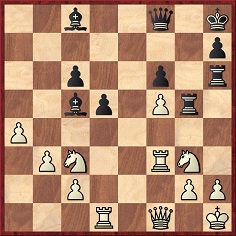

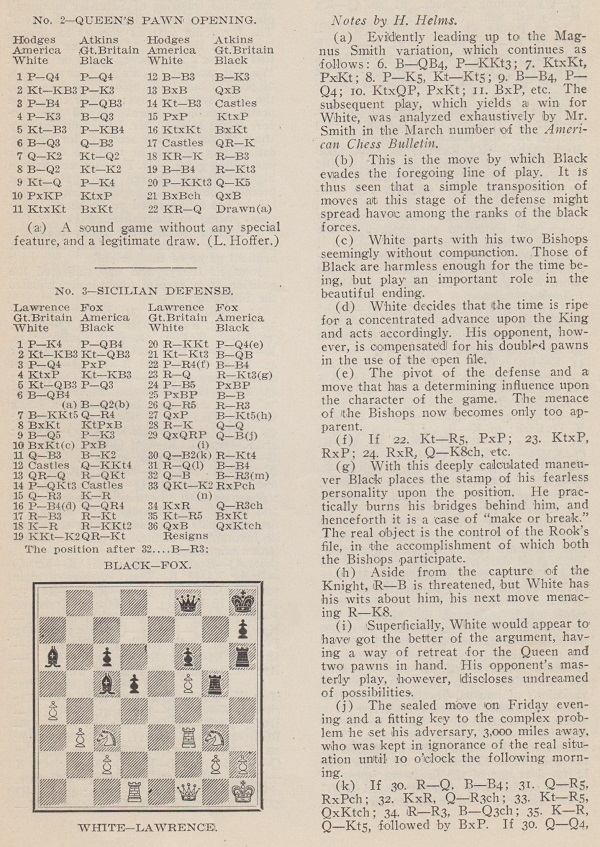

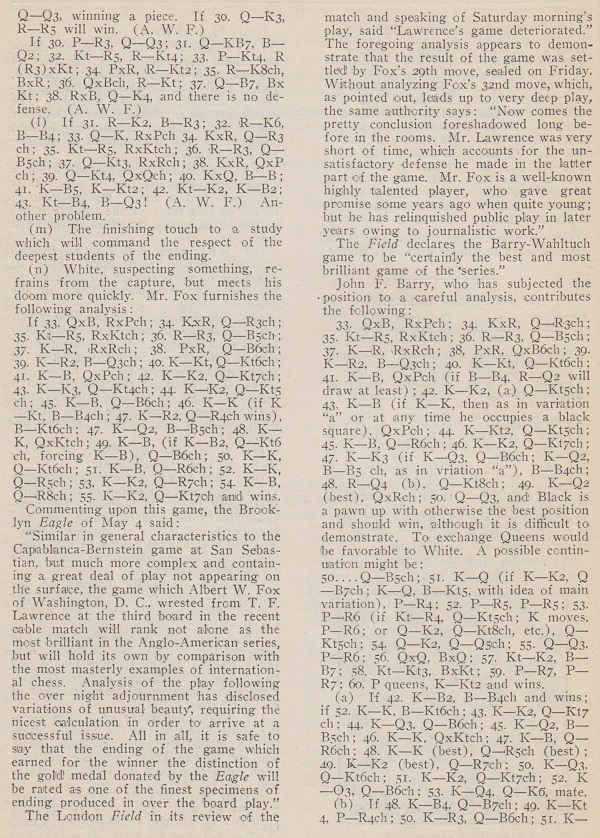

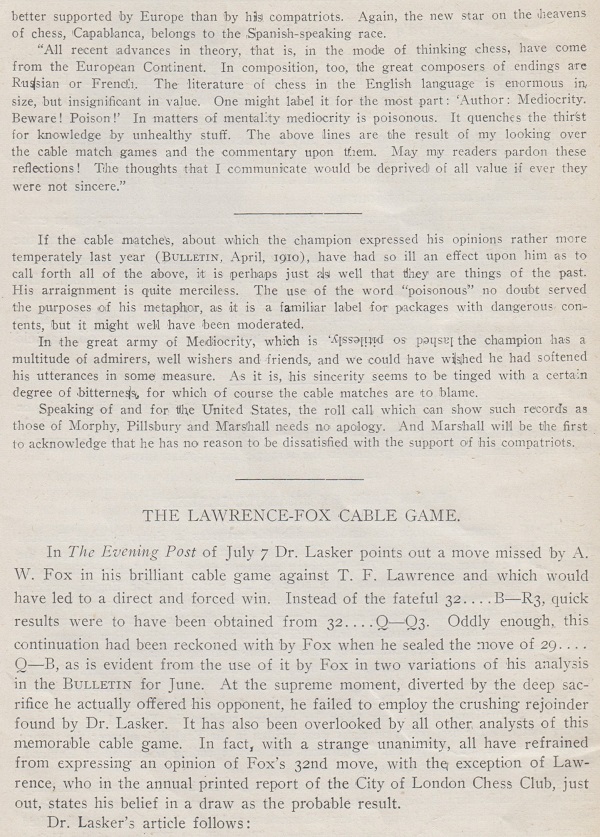

A well-known instance of his rebuttal of lengthy analysis concerns the game between T.F. Lawrence and A.W. Fox in the Great Britain v United States cable match in April 1911. From page 59 of Chernev’s Curious Chess Facts (New York, 1937):

Fox played 32...Ba6; Lasker pointed out 32...Qd6

A greatly expanded account by Chernev, under the heading ‘Lasker cuts combination to one move’, is on pages 146-147 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974). Without a word of direct acknowledgement (or, indeed, any specific source, whether primary or secondary) pages 314-315 of The Joys of Chess by Christian Hesse (Alkmaar, 2011) did little more than repackage Chernev’s material. There was, though, one original touch: Hesse’s anachronism ‘telex game’ (‘Telexpartie’ on page 300 of the original German edition).

The opening of the Lawrence v Fox game was discussed in C.N. 8303 (see too The ‘Magnus Smith Trap’).

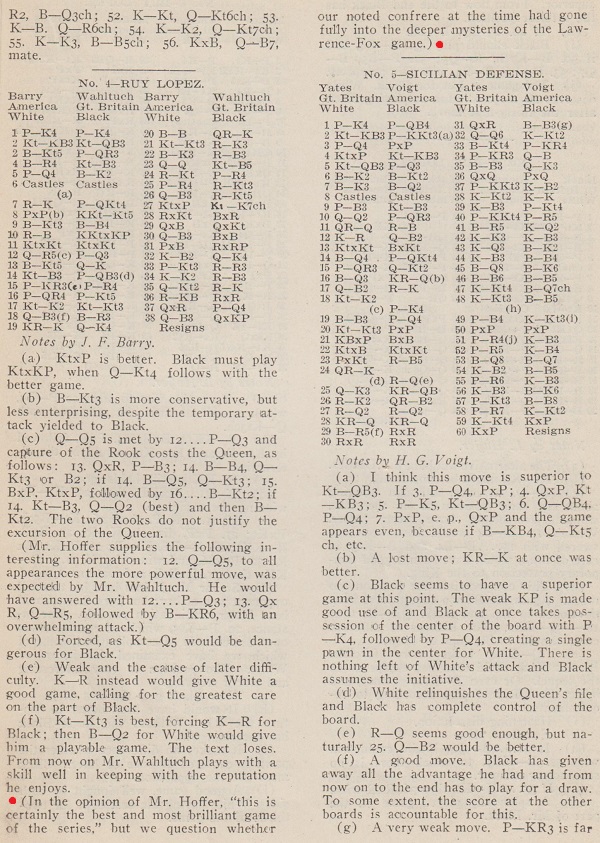

The coverage in the American Chess Bulletin:

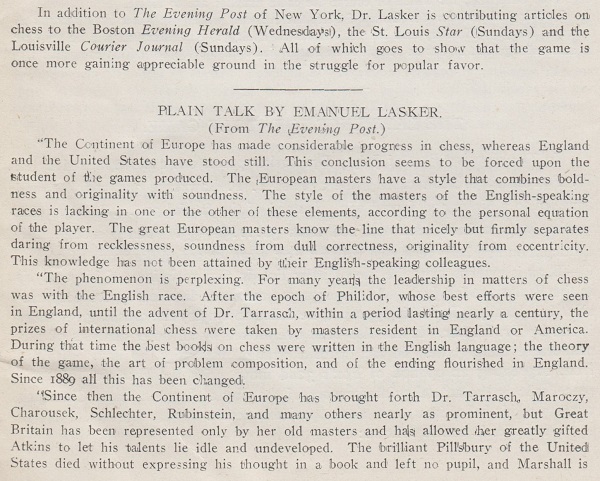

- June 1911, pages 129-131:

- August 1911, pages 171-173:

The ‘Plain Talk’ section was shown in C.N. 8624, which mentioned that the column in the Evening Post had not been traced. We can, though, show page 1 of the Sporting Section of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 4 May 1911, where Hermann Helms discussed the Lawrence v Fox game, i.e. the material reproduced in the June 1911 American Chess Bulletin. Some of the above texts were also given on pages 82-87 of The Year-Book of Chess, 1912 by E.A. Michell (London, 1912).

10038. The Great Jewish Chess Champions

An item that we wrote on pages 23-24 of Kingpin,

Spring

1992 (see too page 197 of Kings, Commoners and

Knaves):

Who was the first to claim the title of world chess champion? Those who thought that it might have been Steinitz will be put right by page 23 of The Great Jewish Chess Champions by Harold U. Ribalow and Meir Z. Ribalow (New York, 1986):

‘Albert Alexandre, a Frenchman who claimed the world title in 1776, was a Jew.’

The co-authors may have meant Aaron Alexandre, even though he was only about ten at the time. Appropriately, the book’s dust-jacket mentions that ‘the Harold U. Ribalow Award is presented annually by Hadassah magazine for an outstanding English-language work of Jewish fiction’.

Another example of the book’s shoddiness is this ‘once’ dialogue on page 28:

‘Steinitz, a German Jew, was also baited by one of his rivals, the fine player Johannes von [sic] Zukertort who, unfortunately, was anti-Semitic. A feud developed between the two and Zukertort once said to Steinitz, “You are not a chessplayer, but a Jew”. The great champion’s cutting reply was, “You, apparently, are neither”.’

10039. Five hours’ silence

From page 20 of the Ribalow book mentioned in the previous item:

‘Madame Chaud [sic – Chaudé] de Silans, one of the better female players, had this contemptuous remark on why her own sex didn’t do better: “Women can’t play chess because you have to keep quiet for five hours.”’

The remark had been ascribed to her by A. Soltis on page 209 of Chess to Enjoy (New York, 1978), sourcelessly as usual.

10040. Pomar on Alekhine

Pages 88-92 of El juzgador de AjedreZ by Eduardo Scala (Madrid, 2014) present a previously unpublished interview with Arturo Pomar (Barcelona, 13 November 1991). In an exchange on page 89 Pomar spoke warmly of Alekhine:

‘– ¿Qué pensaba Alekhine del niňo prodigio, cuando intentó instruirle en esta materia?

– El Dr. Alekhine siempre me trató con mucho afecto. Era un poco impaciente, eso sí; alguna vez se irritaba cuando no coincidíamos en los criterios. Era una buena persona; se tomó con mucha resignación que yo le entablara en el Torneo de Gijón cuando tenía 12 aňos.’

10041. Starbuck miniatures

Patsy A. D’Eramo (North East, MD, USA) submits some short wins by D.F.M. Starbuck:

N.N. – Daniel F.M. Starbuck

Occasion?

(Black gave the odds of his queen’s rook.)

1...Nxd5 2 Nxd5 Qxb2+ 3 Kxb2 Bd4+ 4 Ka3 Bc5+ 5 Kxa4 Bd7+ 6 Ka5 Ra8 mate.

Source: Detroit Free Press, 11 November 1882, page 3.

Daniel F.M. Starbuck – N.N.

Chicago (date?)

(Remove White’s queen’s rook.)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 Qh4+ 4 Kf1 d5 5 Bxd5 c6 6 Bc4

Bg4 7 Nf3 Bxf3 8 Qxf3 Nd7 9 d4 O-O-O 10 Bxf4 Nh6 11 e5 Nf5

12 e6 fxe6 13 Qxc6+ bxc6 14 Ba6 mate.

Source: Detroit Free Press, 23 December 1882, page 3.

N.N. – Daniel F.M. Starbuck

Occasion?

(Remove Black’s queen’s rook.)

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 Bc4 f5 4 Bxg8 Rxg8 5 d4 Nc6 6 Bg5 Be7 7 Bxe7 Qxe7 8 O-O fxe4 9 d5 exf3 10 dxc6 Rf8 11 Qd5 Qg5 12 g3 Qh5 13 Kh1

13...Rf6 14 cxb7 Bxb7 15 Qxb7 Qh3 16 Rg1 Qxh2+ 17 Kxh2 Rh6 mate.

Source: Detroit Free Press, 30 December 1882, page 3.

Daniel F.M. Starbuck – N.N.

Occasion?

(Remove White’s queen’s knight.)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ng5 h5 6 Bc4 Nh6 7 d4 f6

8 Bxf4 fxg5 9 hxg5 Nf7 10 g6 Nd6 11 Bxd6 Bxd6 12 g7 Bg3+ 13 Ke2 Rf8 14 gxf8(Q)+ Kxf8 15 Qf1+ Kg7 16 Qf7+ Resigns.

Source: Detroit Free Press, 6 January 1883, page 3.

N.N. – Daniel F.M. Starbuck

Chicago (date?)

(Remove White’s queen’s knight and Black’s queen’s

rook.)

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 f5 4 Bxc6 dxc6 5 Nxe5 Bd6 6 Qh5+ g6

7 Nxg6 Nf6 8 Qh6 Rg8 9 e5 Rxg6 10 Qe3 Ng4 11 Qe2 Bxe5 12

f4 Re6 13 Kd1 Bd4 14 Qxe6+ Bxe6 15 White resigns.

Source: Detroit Free Press, 25 August 1883, page 3.

Daniel F.M. Starbuck – N.N.

Occasion?

(Remove White’s queen’s rook.)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 g4 5 Nc3 gxf3 6 Qxf3 Qf6 7 Nd5 Qd8 8 O-O d6 9 d4 Be6 10 Qxf4 Nd7 11 Bd2 c6 12 Be1 b5 13 Bh4 Qc8

14 Nc7+ Qxc7 15 Qxf7+ Bxf7 16 Bxf7 mate.

Source: Detroit Free Press, 25 August 1883, page 3.

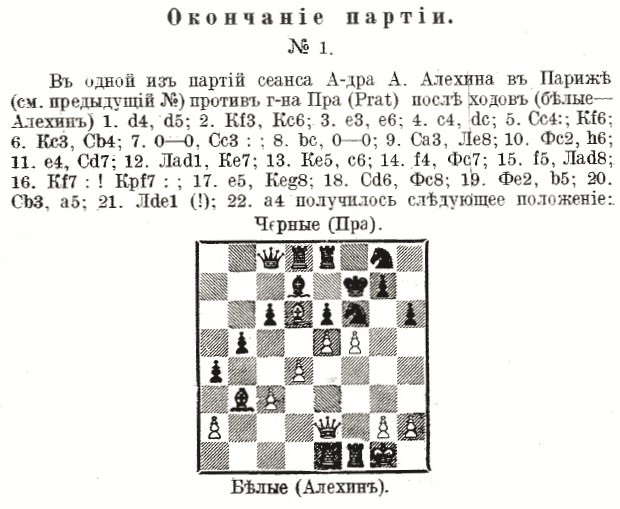

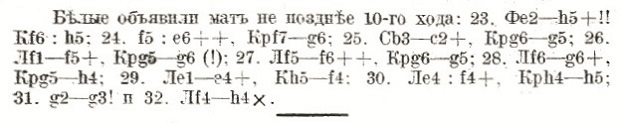

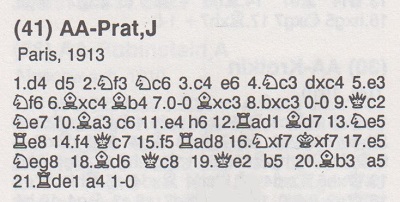

10042. Alekhine v Prat (C.N. 7040)

White announced mate in ten: 22 Qh5+ Nxh5 23 fxe6+ Kg6 24 Bc2+ Kg5 25 Rf5+ Kg6 26 Rf6+ Kg5 27 Rg6+ Kh4 28 Re4+ Nf4 29 Rxf4+ Kh5 30 g3 any 31 Rh4 mate.

C.N. 7040 discussed discrepancies surrounding this famous Alekhine victory, and more are added now.

As regards Black’s identity, we have never seen a full name, but only ‘Prat’, with or without an initial. Our earlier item pointed out that in the English, German/Dutch and French editions of Alekhine’s first Best Games book the initial was given as M., J. and N. respectively. A fourth option, I., is in the Russian edition (Moscow and Leningrad, 1927). Although ‘M. Prat’ is the most common version, a misunderstanding may have arisen through M. being an abbreviation for Monsieur (as discussed, in another context, in C.N. 6693).

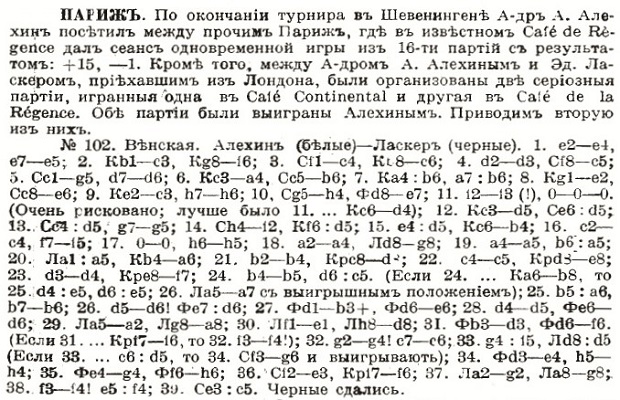

‘J. Prat’ was the name when the 22 Qh5+ finish was published on page 415 of La Stratégie, October 1913 (reproduced in C.N. 7040). The earliest occurrence of the full game-score that we can cite is on pages 286-287 of Shakhmatny Vestnik, 15 September 1913, shown here courtesy of the Royal Library in The Hague:

The heading stated that Alekhine played ‘against Mr Prat’; г-на is an abbreviation of the genitive singular form Господина (‘Mr’).

The Royal Library has also kindly provided the item on page 273 of the 1 September 1913 edition of Shakhmatny Vestnik to which the 15 September issue referred:

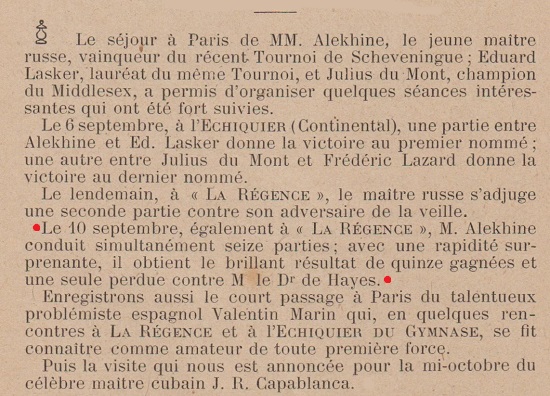

The report that Alekhine’s exhibition in Paris comprised 16 games (+15 –0 =1) corresponds to the information on page 360 of La Stratégie, September 1913:

As previously shown, page 415 of the October 1913 issue

of La Stratégie also gave the date of the display

as 10 September 1913. The fact that the above issue of Shakhmatny

Vestnik was, formally at least, dated 1 September is

not a stumbling-block, given the 13-day difference between

the Julian and Gregorian calendars and the inclusion of

Alekhine’s game against Edward Lasker, played on 7

September. It is, though, unclear why ‘August 1913’ was in

the heading to the Prat game on page 119 of volume one of

Complete Games of Alekhine by J. Kalendovský and V.

Fiala (Olomouc, 1992). Page 87 of Alexander Alekhine’s

Chess Games, 1902-1946 by L.M. Skinner and R.G.P.

Verhoeven (Jefferson, 1998) put only ‘1913’ (and ‘J.

Prat’), but the previous page duly referred to the

16-board display on 10 September 1913.

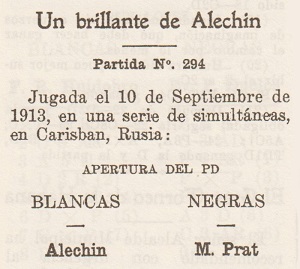

Although page 192 of Capablanca-Magazine, 15 November 1913 also dated the game ‘10 September 1913’, there was a mysterious assertion that it was played in ‘Carisban, Russia’:

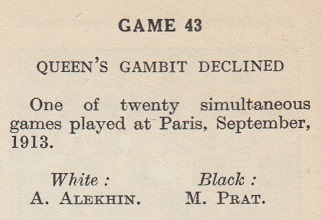

The English and French editions of Alekhine’s first Best Games book stated that the simultaneous display consisted of 20 games, which contradicts the reports in Shakhmatny Vestnik and La Stratégie. Below are the headings in the various editions of Alekhine’s book, in chronological order of publication (London, 1927; Moscow and Leningrad, 1927; Berlin and Leipzig, 1929; The Hague, 1929; Rouen, 1936):

All these books recorded that the game began 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 dxc4 5 e3 Nf6 6 Bxc4, whereas Shakhmatny Vestnik and Capablanca-Magazine had 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 e3 e6 4 c4 dxc4 5 Bxc4 Nf6 6 Nc3. The latter order is not among the five versions of the game in FatBase 2000, although the CD included 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 dxc4 5 e3 Nc6 6 Bxc4.

The lengthiest coverage of Alekhine v Prat that we have seen is on pages 199-215 of How to Think Ahead in Chess by I.A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1951). The worst treatment is on page 308 of The Games of Alekhine by Rogelio Caparrós and Peter Lahde (Brentwood, 1992). Alekhine’s brilliant conclusion beginning with 22 Qh5+ was not even mentioned:

10043. The Manual

‘Lasker’s Manual has claims to be the most important chess book ever written.’

Source: C.J.S. Purdy on page 240 of the November 1960 Chess World.

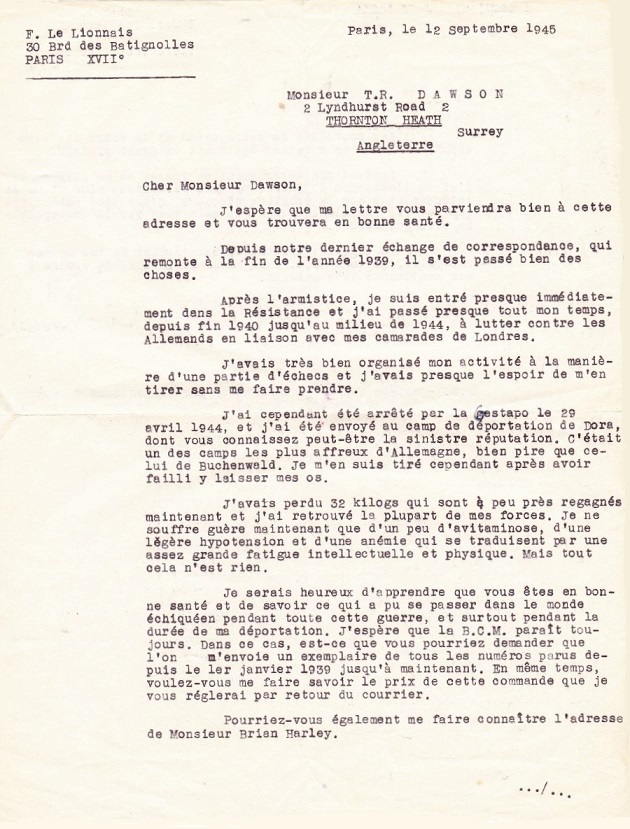

10044. Le Lionnais (C.N. 9295)

From the archives of his father, D.J. Morgan, Professor Lord Morgan (Oxford, England) provides a letter dated 12 September 1945 from François Le Lionnais to T.R. Dawson. Le Lionnais wrote that on 29 April 1944 he had been arrested by the Gestapo and deported to Dora, a concentration camp ‘much worse than Buchenwald’.

T.R. Dawson’s address had changed from 2 Lyndhurst Road, Thornton Heath to 31 Clyde Road, East Croydon over five years previously, as announced on page 231 of the July 1940 BCM.

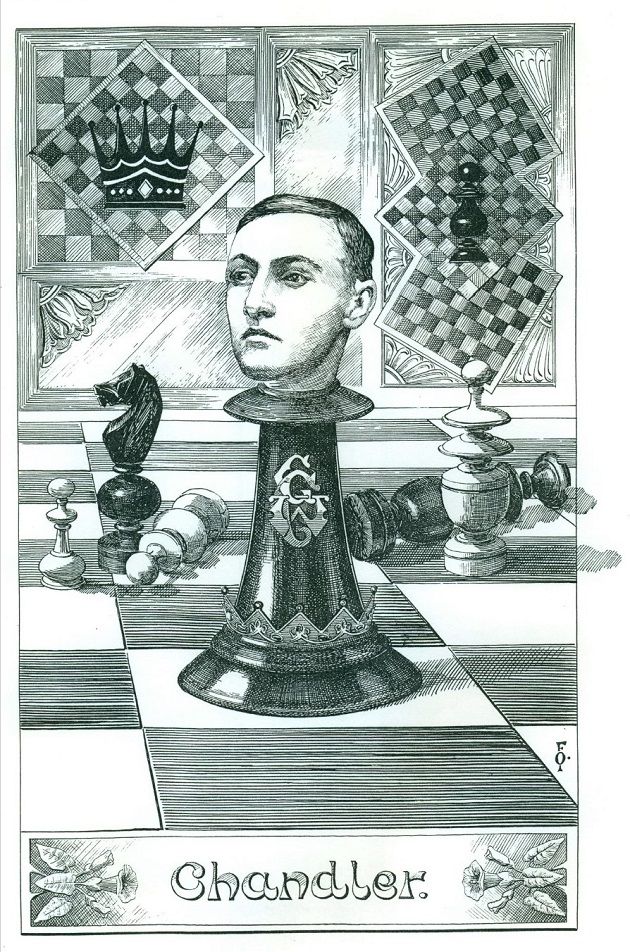

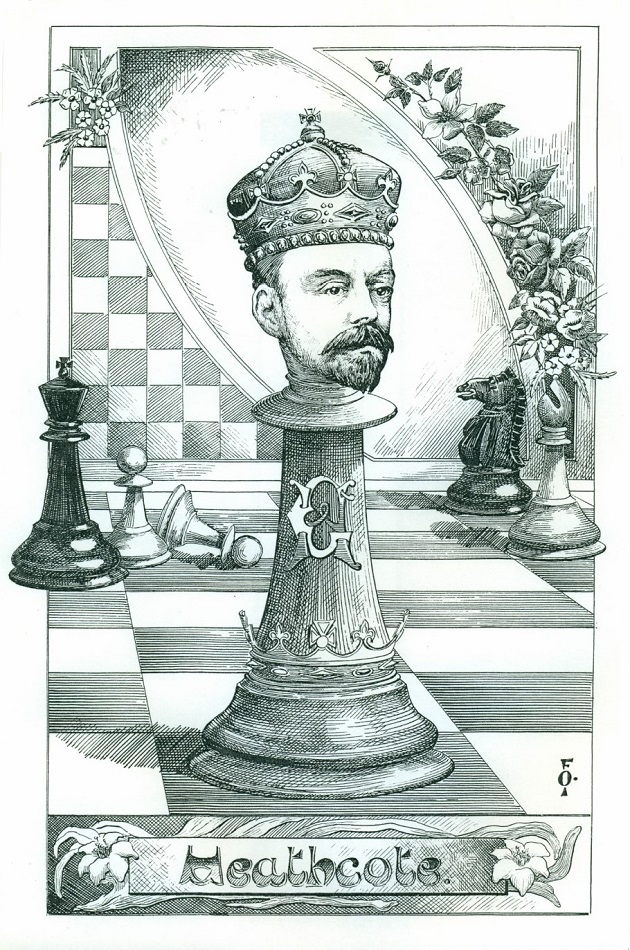

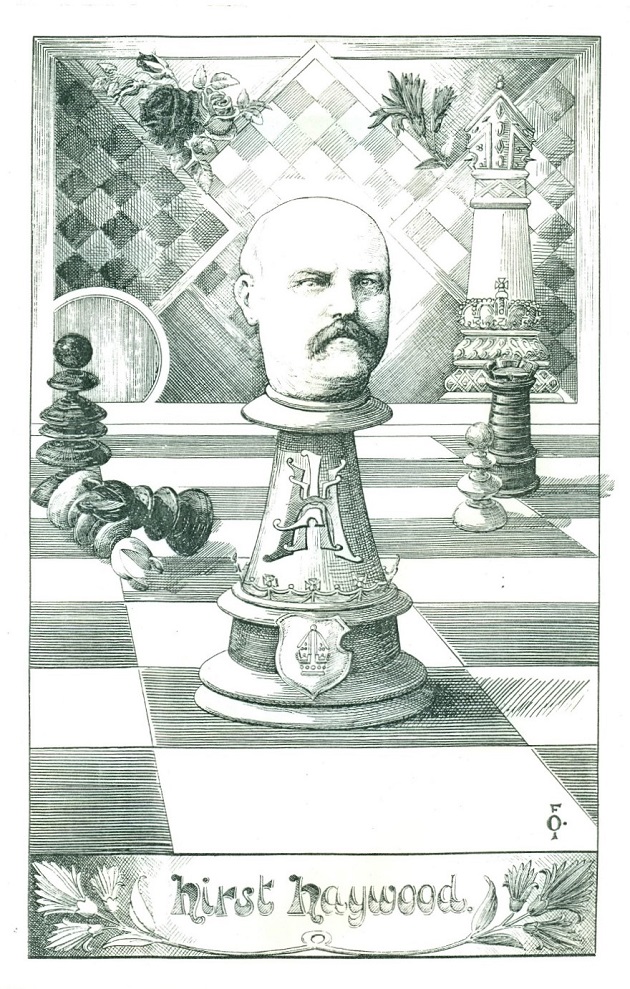

10045. Frederick Orrett

Three more portraits by Frederick Orrett submitted by Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

Guy Wills Chandler

Godfrey Heathcote

J. Hirst Haywood

10046. Philidor

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘In today’s Times, page 19 of the second section, Raymond Keene writes:

“Gordon Cadden’s historical research in the June issue of the British Chess Magazine (see yesterday’s column) performs a further service by correctly establishing not just the correct location of François-André Philidor’s grave but also the accurate time of his death, which had previously been mis-stated as August 24, 1795. In fact, it was August 31 of that year. Cadden’s article contains one unfortunate error in the caption to the match between Howard Staunton and Pierre de Saint Amant in Paris, the contest in which Staunton developed many of Philidor’s theories. This match, of course, took place in 1843 not 1834 as given in the article.”

In reality, it has long been common knowledge that Philidor died on 31 August; C.N. 6005 pointed out that “there was doubt about the correct date until the mid-1920s”. George Cadden’s article on pages 357-362 of the June 2016 BCM, an interesting read, made no claim to have discovered anything new about the date.

Raymond Keene takes nearly 50 words to point out an obvious caption error in the BCM, but when will he correct the many factual blunders which he himself made in his Times and Sunday Times columns over a mere four-day period last month? On 15 June 2016 I wrote a brief article cataloguing them.’

| First column | << previous | Archives [144] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.