Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [190] | next >> | Current column |

11844. Warren Goldman

As reproduced on page 360 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, C.N. 2077 gave an appreciative welcome to Carl Schlechter! Life and Times of the Austrian Chess Wizard by Warren Goldman (Yorklyn, 1994), a 537-page hardback published posthumously.

Although our correspondence with Goldman chiefly concerned his Schlechter manuscript, already largely completed by 1984, an exception was his letter of 23 May 1990. After reporting that five days previously he had retired from civilian employment with the US Army (Europe) recreation program, he offered a few chess reminiscences:

A Christmas card (1991) stated that he expected the Schlechter book to be published the following year, and below is an extract from his final letter to us, dated 6 March 1992:

On 5 January 1993 Hildegard Goldman wrote to us:

‘... my dear husband passed away last 26 June after suffering a light stroke, followed, while in the head clinic of the University of Heidelberg, by complications and heart failure after days in the intensive care unit of the clinic. My only solace is that he did not suffer ...’

Regarding Warren Goldman’s work as an opening theoretician, see issue 15 of Kaissiber, which carried a photograph of him on the front cover.

11845. Euwe and Capablanca

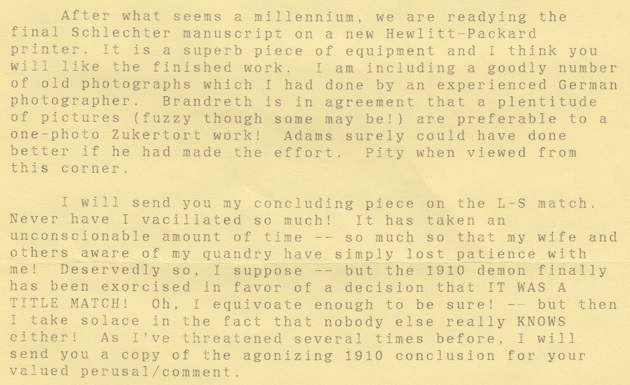

A letter from Max Euwe dated 27 May 1974:

The second question concerned his likely action had he defeated Alekhine in 1937. See too page 324 of our monograph on Capablanca.

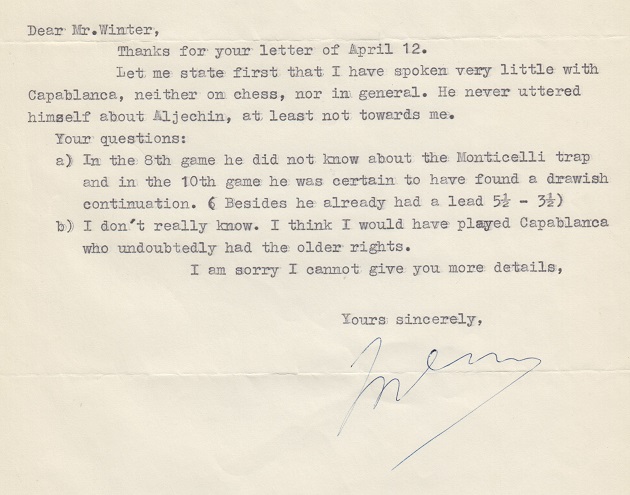

11846. Prokofiev

Above is the front of the dust-jacket of S. Prokofiev Autobiography Articles Reminiscences (Moscow, 1959). From pages 101-102, regarding the Moscow, 1936 tournament:

The original, on page 4 of Izvestia, 30 May 1936:

Concerning the first part of the article, an English translation by Kenneth Neat is on pages 80-81 of our book on Capablanca.

From opposite page 104 of the above-mentioned Prokofiev anthology:

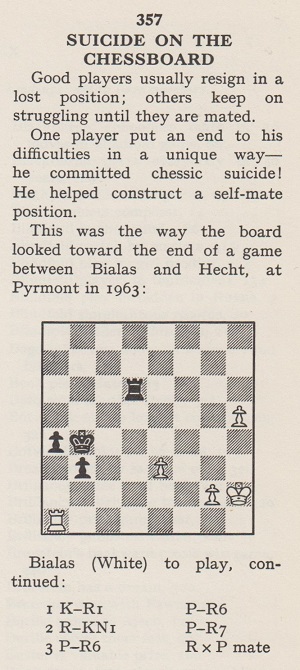

11847. ‘Suicide on the Chessboard’ (C.N.s 9987 & 10019)

From page 193 of Chernev’s Wonders and Curiosities of Chess, as shown in C.N. 9987

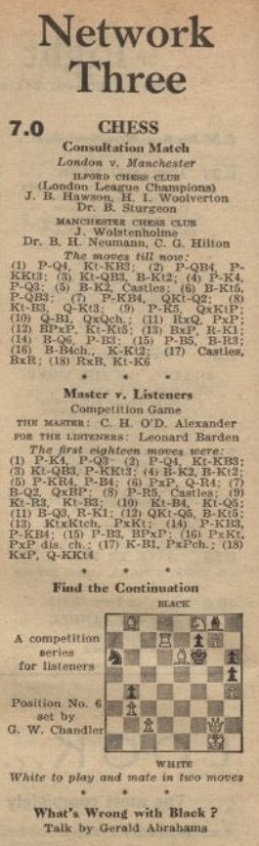

Hajo Markus (Walsrode, Germany) notes that a good source for the game Bialas v Hecht, Bad Pyrmont, 1963 is the tournament bulletin:

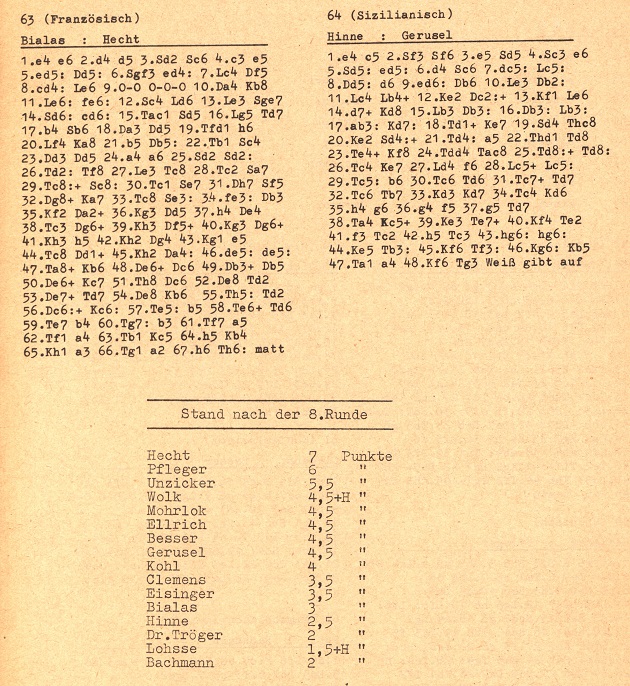

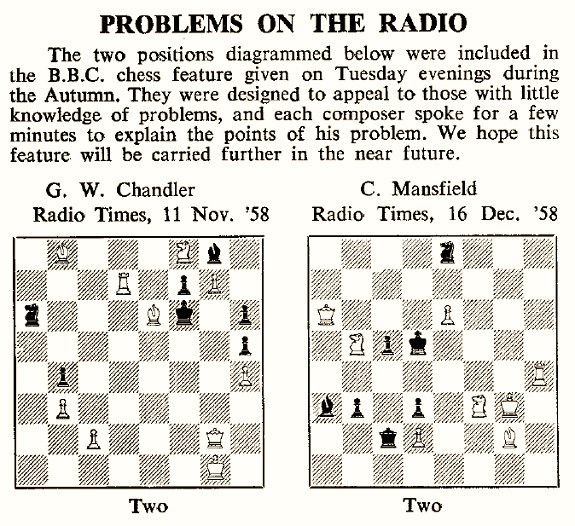

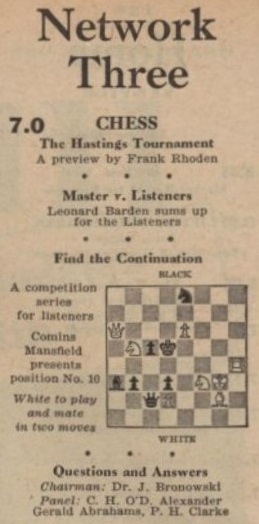

11848. Chess problems on the radio

An addition to Chess and Radio has been submitted by Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England), from page 2 of The Problemist, January 1959:

We add the related features in the Radio Times:

7 November 1958, page 34 (concerning a broadcast on 11 November 1958)

12 December 1958, page 30 (concerning a broadcast on 16 December 1958)

11849. The Queen’s Retreat

Browsing on the Radio Times website, we have noted the billing for a 45-minute radio play, The Queen’s Retreat by Tanika Gupta, broadcast on BBC Radio Four on 1 June 1999.

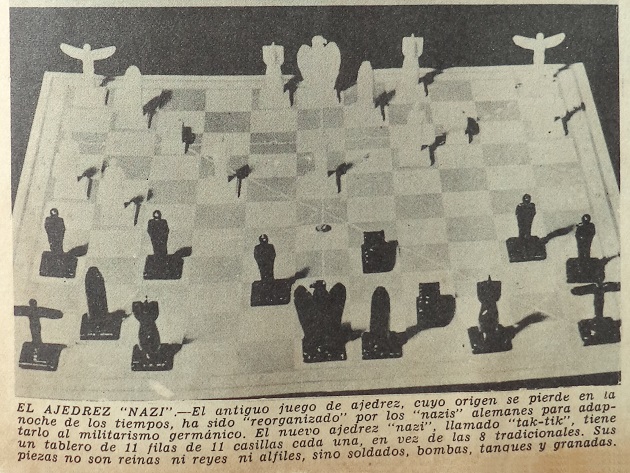

11850. Nazi chess

Yandy Rojas Barrios (Cárdenas, Cuba) sends two photographs in the 26 December 1937 edition of Carteles:

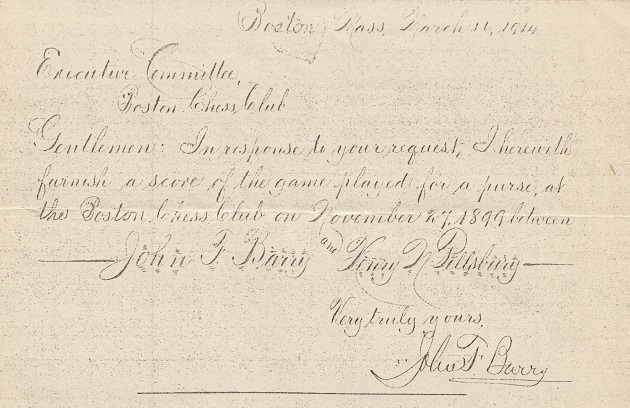

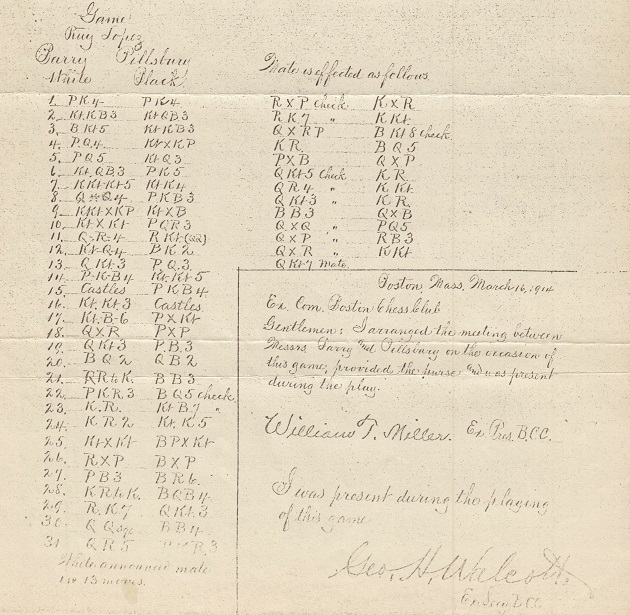

11851. Barry v Pillsbury (C.N.s 4582 & 6979)

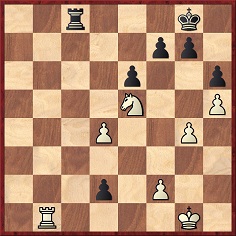

The conclusion of Barry v Pillsbury, Boston, 1899 (White to move):

White announced mate in 13

In 1989 Richard Lappin (Jamaica Plain, MD, USA) sent us the following, from the archives of the Boylston Chess Club (Boston):

We note that this document was referred to on page 30 of the March-April 1978 issue of Chess Horizons.

11852. A win by Hugh Myers with 1 e4 c5 2 a4

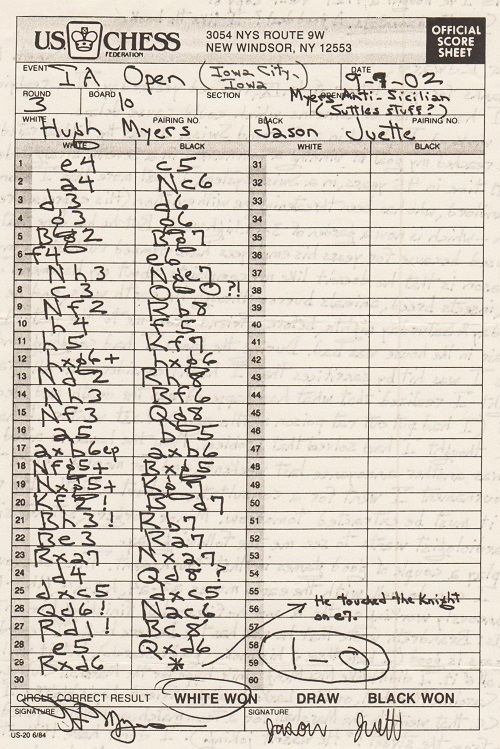

On 15 September 2002 Hugh Myers (Davenport, IA, USA) sent us his win against Jason Juette in Iowa City earlier that month:

1 e4 c5 2 a4 Nc6 3 d3 d6 4 g3 g6 5 Bg2 Bg7 6 f4 e6 7 Nh3 Nge7 8 c3 O-O 9 Nf2 Rb8 10 h4 f5 11 h5 Kf7 12 hxg6+ hxg6 13 Nd2 Rh8 14 Nh3 Bf6 15 Nf3 Qg8 16 a5 b5 17 axb6 axb6 18 Nfg5+ Bxg5 19 Nxg5+ Kg7

20 Kf2 Bd7 21 Bh3 Rb7 22 Be3 Ra7 23 Rxa7 Nxa7 24 d4 Qd8 25 dxc5 dxc5 26 Qd6 Nac6 27 Rd1 Bc8 28 e5 Qxd6 29 Rxd6.

Overleaf, Hugh Myers, who was aged 72 at the time, commented to us that the game ‘... shows again that I can do well with the early moves a2-a4, h2-h4, Nh3-Nf2-Nh3, and then simultaneously working on the a and h-files – but finishing him on the d-file’.

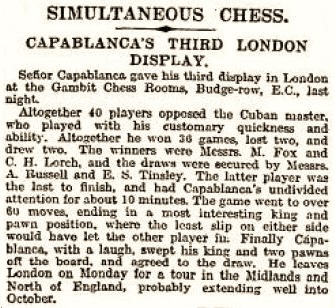

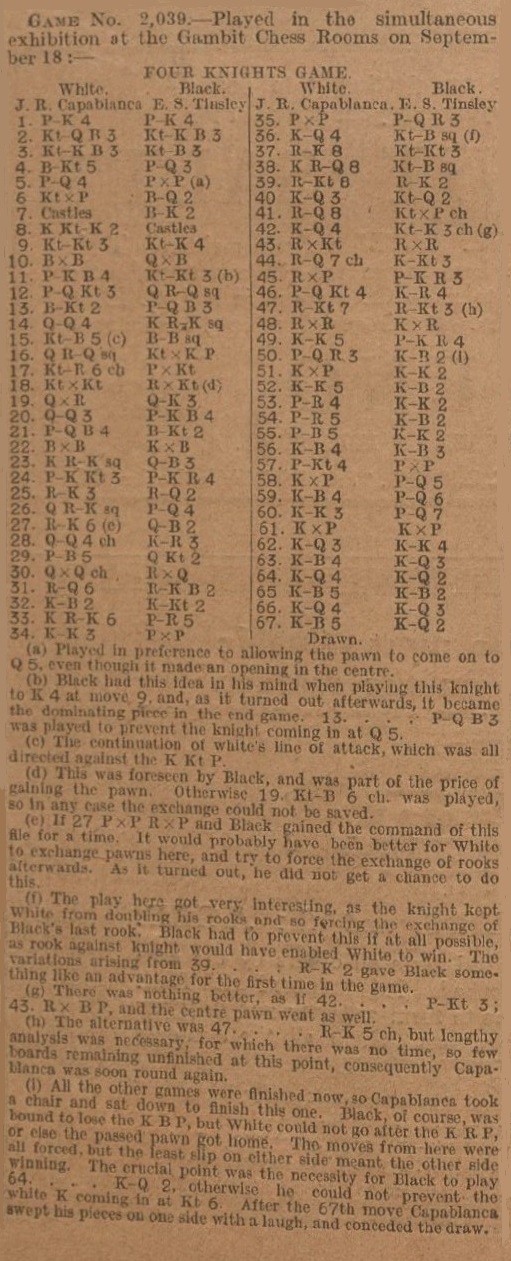

11853. Capablanca v E.S. Tinsley

From The Chess Tinsleys:

As mentioned on page 99 of our book on Capablanca, E.S. Tinsley drew with the Cuban in a simultaneous display at the Gambit Chess Rooms, London on 18 September 1919 (BCM, October 1919, page 342). The report below appeared in The Times, 19 September 1919, page 8:

The game was misdated ‘1918’ in three editions of Capablanca’s games compiled by Rogelio Caparrós (Yorklyn, 1991, Barcelona, 1993 and Dallas, 1994). The score was also given on pages 245-247 of Capablanca in the United Kingdom (1911-1920) by V. Fiala (Olomouc, 2006), from The Times Weekly Edition, 10 October 1919.

Below we now show that column by E.S. Tinsley (page iv):

The column has been forwarded to us by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA), courtesy of the New York Public Library (General Research Division).

In the Fiala book there were, of course, a few mistranscriptions of the Times Weekly Edition annotations. Moreover, Tinsley gave White’s second move as Nc3, and not Nf3.

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 Bb5 d6 5 d4 exd4 6 Nxd4 Bd7 7 O-O Be7 8 Nde2 O-O 9 Ng3 Ne5 10 Bxd7 Qxd7 11 f4 Ng6 12 b3 Rad8 13 Bb2 c6 14 Qd4 Rfe8 15 Nf5 Bf8 16 Rad1 Nxe4

17 Nh6+ gxh6 18 Nxe4 Rxe4 19 Qxe4 Qe6 20 Qd3 f5 21 c4 Bg7 22 Bxg7 Kxg7 23 Rfe1 Qf6 24 g3 h5 25 Re3 Rd7 26 Rde1 d5 27 Re6 Qf7 28 Qd4+ Kh6 29 c5 Qg7 30 Qxg7+ Rxg7 31 Rd6 Rf7 32 Kf2 Kg7 33 Ree6 h4 34 Ke3 hxg3 35 hxg3 a6 36 Kd4 Nf8 37 Re8 Ng6 38 Red8 Nf8 39 Rb8 Re7 40 Kd3 Nd7 41 Rd8 Nxc5+ 42 Kd4 Ne6+ 43 Rxe6 Rxe6 44 Rd7+ Kg6 45 Rxb7 h6 46 b4 Kh5 47 Rg7 Rg6 48 Rxg6 Kxg6 49 Ke5 h5 50 a3 Kf7 51 Kxf5 Ke7 52 Ke5 Kf7 53 a4 Ke7 54 a5 Kf7 55 f5 Ke7 56 Kf4 Kf6 57 g4

57...hxg4 58 Kxg4 d4 59 Kf4 d3 60 Ke3 d2 61 Kxd2 Kxf5 62 Kd3 Ke5 63 Kc4 Kd6 64 Kd4 Kd7 65 Kc5 Kc7 66 Kd4 Kd6 67 Kc4 Kd7 Drawn.

Concerning the position in the second diagram, in a letter to us dated 3 June 1991 G.H. Diggle (then aged 88) diffidently suggested that Tinsley had missed a win by not playing 57...h4. That is confirmed by a computer check, which also indicates that Capablanca erred with 56 Kf4 (instead of 56 f5+, which draws).

11854. Edge, Morphy and Staunton

The quartet of feature articles Edge, Morphy and Staunton, A Debate on Staunton, Morphy and Edge, Supplement to ‘A Debate on Staunton, Morphy and Edge’ and Edge Letters to Fiske has expanded so much that certain sections have inevitably become amorphous.

Is it nonetheless possible at this stage to draw further conclusions in some of the discussion strands, such as F.M. Edge’s dependability as a chronicler?

11855. John Townsend on F.M. Edge

Frederick M. Edge (C.N. 9133)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘The question posed in C.N. 11854 referred specifically to Edge’s dependability “as a chronicler”, but perhaps it will help to consider his dependability as a person, especially considering that in recent years our knowledge of Edge’s life and character has advanced so markedly. Thanks for that are mainly due to Chess Notes and the “quartet” of feature articles mentioned in C.N. 11854. As a result, we have access today to much information which was not known to twentieth-century historians, such as Lawson and Sergeant, and this has particular bearing on his dependability.

In what follows, “Feature Article 1” means Edge, Morphy and Staunton, and “Feature Article 2” means Edge Letters to Fiske.

Overall, the picture of Edge which has emerged in recent years is an unfavourable one, which casts serious doubts over his trustworthiness and honesty.

Edge was born into a respectable family in 1830 in Westminster, the son of a manufacturing businessman, and attended a boarding school on Jersey, before concluding his education at King’s College London; however, he left after one year, having been frequently absent from lessons and examinations. (Feature Article 1.)

The diaries of Thomas Butler Gunn, which were reported to Chess Notes by Harrie Grondijs, contain surprising revelations and new insights into Edge’s lifestyle and character (Feature Article 1). However, there is no indication that the diaries contain other than a faithful record; the writer shows no malice towards Edge, and, if anything, something of an affection for “little Edge” comes across.

The diary entry of 22 March 1858 recalls that as a young man Edge “squandered money, went to races, betted ...” (Feature Article 1). Exactly how early he fell into debt is not clear, but his habit of borrowing money and not paying it back became a familiar complaint by his associates on either side of the Atlantic, both in the 1850s in New York, and in the 1860s in England.

He “ran off” to Paris, and was subsequently a journalist in New York by 1855, where he “gambled away all his money” (Feature Article 1). The diary entry of 11 April 1856 mentions that he went through a period in New York of being “desperately hard up” and sleeping rough, including in timber yards. (Feature Article 1.)

In 1857 he “married a little Alsatian prostitute” (in the words of the diary), who had previously lived with him as his “mistress”.

At sundry times, he lived a Bohemian lifestyle and eked out a scrounging existence (Feature Article 1). A diary entry for 22 March 1858 notes that Edge had returned to England owing money to Haney and had even “borrowed from the boy who waits at Haney’s tavern without repaying him!” (Feature Article 1.)

If it is true, as was reported in a diary entry of 11 May 1859, that Edge abused his position as a journalist to threaten police officers unless they appointed his own choice of officer, then he must have been fortunate not to face criminal charges (Feature Article 1). He allegedly threatened to be “down upon” the officers in case of refusal. As it was, his only punishment was that he lost his job.

The amount of trust the diarist Gunn felt in Edge is amusingly, but tellingly, illustrated by a diary entry (volume 21, page 194: 23 January 1863) describing a visit by Edge to his room after he had gone to bed. When Edge turned the conversation to his money difficulties, Gunn recalls how he reacted:

“I took the hint by jumping out of bed and securing my purse ...”

Edge’s scrounging extended to finding a bed to sleep in. Volume 21, pages 193-196 (23 January 1863) refers to Edge moving about the house to find someone else’s bed to share, in some cases without the knowledge of the bed’s principal occupier. Edge’s nocturnal wandering was objected to by other residents. His reason was that his own landlady had inconveniently asked for the rent.

It is difficult to see how such a person could have been taken seriously in Victorian England; Gunn’s portrayal of him sometimes resembles that of a music-hall character. Yet it appears that Edge was capable of being credible in face-to-face situations, thanks to his personality. He even obtained an interview in 1860 with the Foreign Secretary, Lord John Russell (Feature Article 1). Gunn suggested (volume 9, page 107: 22 March 1858) that his impudence may have assisted him on such occasions:

“He did well as a reporter on the Herald, for his matchless impudence – which never looked like impudence in Edge – stood him in good stead. He would have walked up to the President with ‘Now I want you to tell me all about &c &c.’”

In London in 1865, Edge spent a short time in the debtors’ prison in Whitecross Street (Feature Article 1). In 1867, he had a job with the Reform Society in Manchester; it ended in a libel case in which Edge sued the society’s honorary secretary of the northern department, evidently for implying that he had attempted to divert money intended for the society to his own pocket (Feature Article 1). In reality, it seemed impossible to recognize a libel in the words of which he complained. He cleared his name after a settlement was suggested by the judge, but it came out during evidence that Edge “had been borrowing money from first one person and then another” and that he had acquired a bad reputation for it. (Feature Article 1.) That was consistent with the complaints which his associates had made about him in New York.

The various episodes described above strongly suggest that Edge was not a person to be trusted, and was also capable of being dishonest and corrupt. One can easily imagine that his lack of trustworthiness could have adversely affected the negotiations for the proposed Staunton-Morphy match, and there is, clearly, scope for that to have happened. Yet it is very difficult to point to concrete examples, and it is often not clear for which actions Edge was responsible, as opposed to Morphy.

For the match to come off, successful negotiations were needed which had to be based on satisfactory relations between the two sides. Staunton was not obliged to play, and he may have felt that he was making a personal sacrifice in trying to find the time for it. It was important, therefore, for Morphy to retain his goodwill if he wanted a match. In the event, relations deteriorated, and Staunton has taken the bulk of the blame for that, and for the failure of the match. However, several historians in the past have noted Edge’s anti-Staunton bias, and one wonders to what extent it was a deliberate policy. Was he “down upon” Staunton in the same way as he threatened to be “down upon” the police officers? His hostile attitude, to give just one example, is illustrated in a letter dated 6 August 1858 (page 2), in which he referred to Staunton as “the ‘Chess Pariah’ of the London world” (Feature Article 2). Staunton had no shortage of enemies, and also many supporters, but use of the word “Pariah” seems excessive. The bias appears pronounced in Edge’s book on Morphy.

Lawson was, surely, mistaken when he asserted, on page 109 of The Pride and Sorrow of Chess, that “Morphy was a self-willed person” who “made his own decisions” and that “Edge always played a subordinate role in Morphy’s affairs”. Examples are available which show, on the contrary, that Edge played a controlling and influential part in Morphy’s affairs, and that he was of a scheming mentality. Edge it was who insisted on the Anderssen match, despite opposition from Morphy and his family; Edge who engineered Morphy’s “jeremiad” to Lord Lyttelton, whereas Morphy would have taken no action; and who claimed to have taken letters from Morphy’s pocket, and so on. Lawson appears to have underestimated this aspect of Edge.

On page 101 of A Century of British Chess, P.W. Sergeant remarked that he did not consider Edge a liar, while Lawson (page 109 of The Pride and Sorrow of Chess) merely supported that view. However, there is no indication that either of them enquired into Edge’s background before making that judgement. Did the mere fact of his association with Morphy give him respectability in their eyes? Sergeant did, at least, acknowledge Edge’s anti-Staunton bias.’

11856.

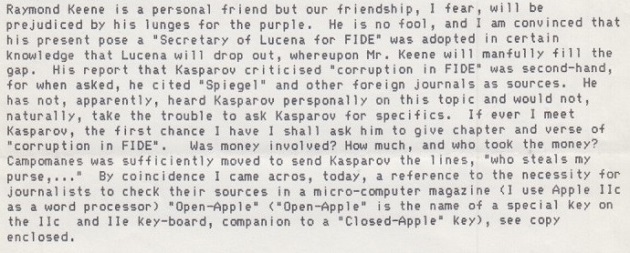

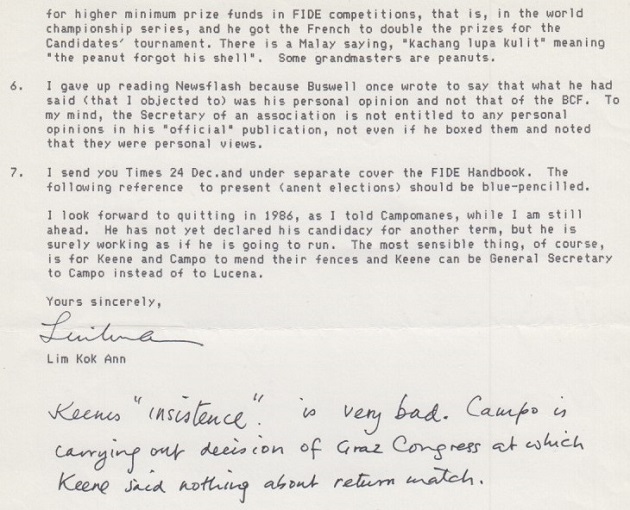

Letters (1986) from the FIDE General Secretary

Below are the key parts of a letter to us dated 1 January 1986 from the General Secretary of FIDE, Dr Lim Kok Ann:

We also reproduce here another letter from Lim Kok Ann, dated 13 January 1986:

11857. Tuesday

A comment of ours in Instant Fischer (‘Kasparov has trouble not contradicting himself over what he said last Tuesday’) was quoted by Olimpiu G. Urcan on Twitter on 23 February 2021, accompanied by a clip from the 1937 Laurel and Hardy film Way Out West in which, replying to ‘What did he die of?’, Stan Laurel said, ‘I think he died of a Tuesday ...’ A question of language arises: why, in such cases, is Tuesday the most effective day to mention?

We have put the matter to Stephen Fry, who replies:

‘No question that Tuesday is the funniest day. Always has been. Though Douglas Adams came up with that line “This must be Thursday. I never could get the hang of Thursdays” which shows Thursday comes in a good second. Monday wouldn’t work because there’s a reason why “I don’t like Mondays” as Bob Geldof sang. Wednesday is just too much of a mouthful to zing. Friday is too associated with payday and the end of the week, and the other two days are reserved for weekend properties. So perhaps it’s more a process of elimination … I wonder if any continental languages have equivalents. Is Mittwoch as funny as Dienstag?

Tuesday doesn’t follow the “hard C” rule (see the film The Sunshine Boys for a wonderful scene involving hard Cs).

Noël Coward often pondered why some place names are funny, and even claimed that in America funny place names are only funny because the word itself is inherently amusing – “Schenectady” “Kalamazoo” “Albuquerque” – whereas the British find certain places funny for less obvious reasons: “Neasden” and “Purley” might elicit a laugh, whereas “Hendon” and “Portsmouth” for example wouldn’t. Hugh [Laurie] and I got much mileage out of Uttoxeter, mileage that Exeter or Huddersfield would never have offered …’

11858.

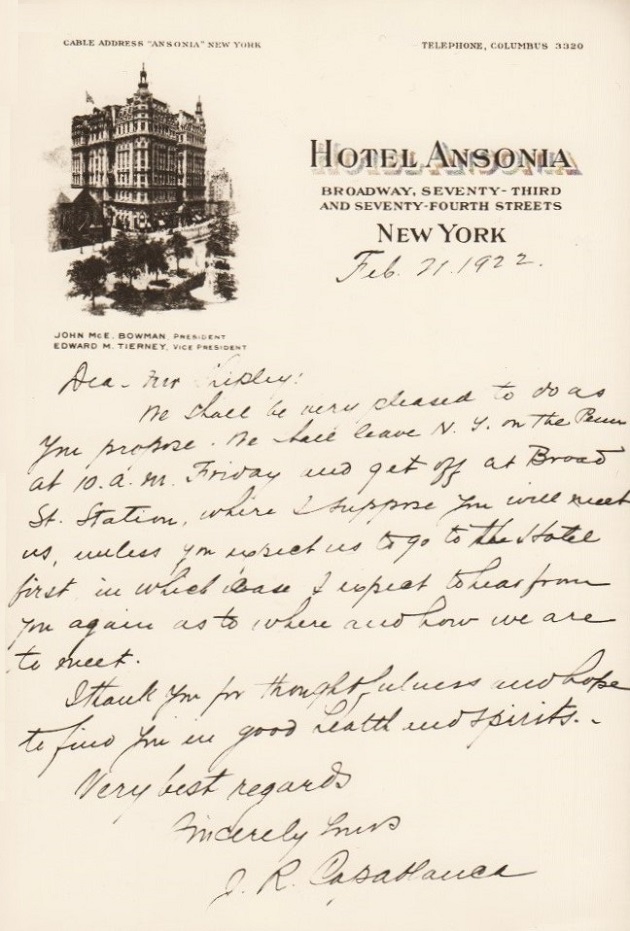

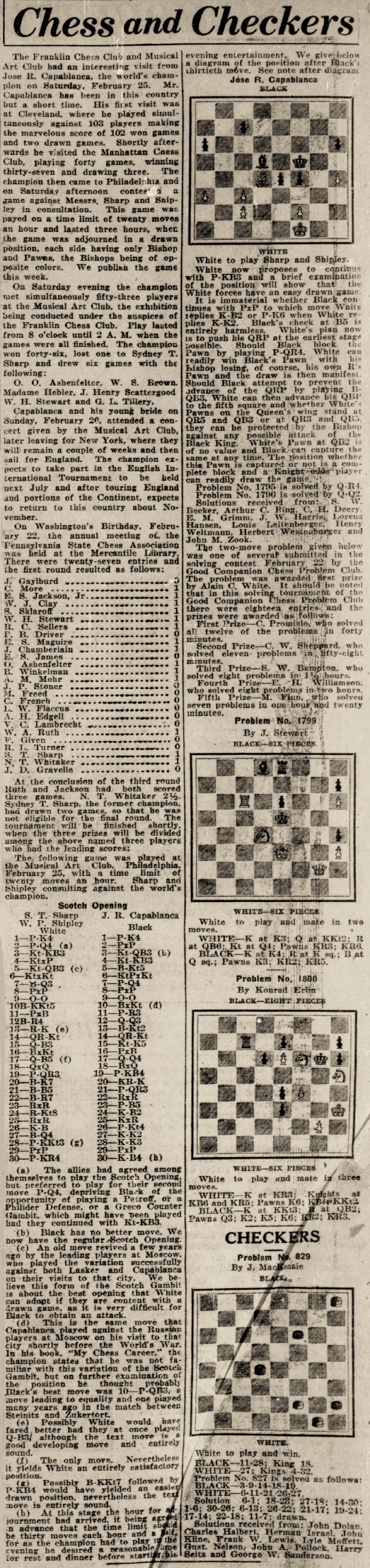

Capablanca and Shipley in Philadelphia

On Tuesday, 21 February 1922 Capablanca sent Walter Penn Shipley this letter, of which we have a copy:

Capablanca’s visit to Philadelphia was discussed on pages 403-404 of Walter Penn Shipley Philadelphia’s Friend of Chess by John S. Hilbert (Jefferson, 2003), and Dr Hilbert has forwarded Shipley’s column in the Philadelphia Inquirer of 12 March 1922, page 6:

The consultation game is familiar from its appearance on page 82 of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975).

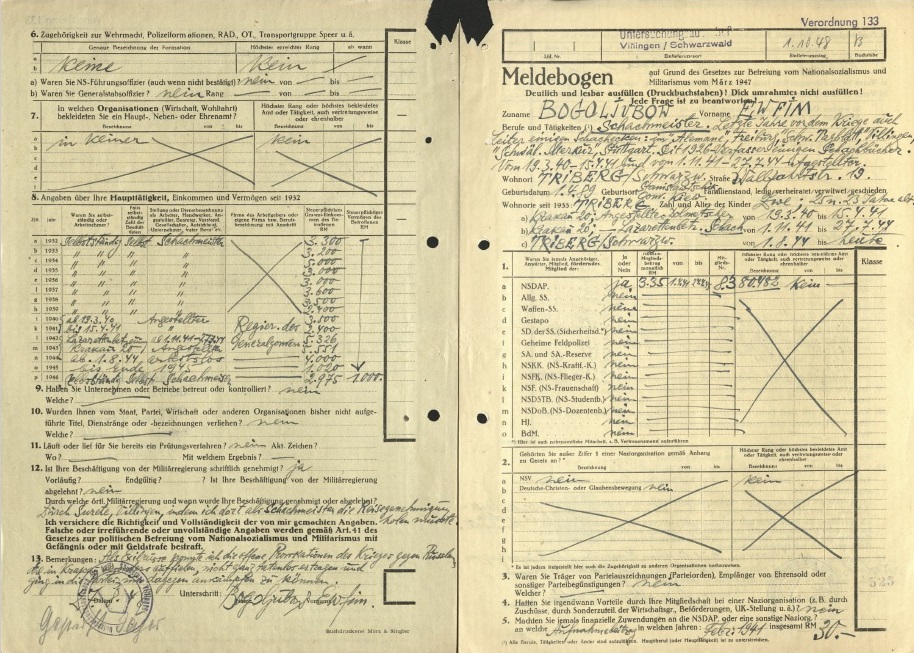

11859. The denazification of Bogoljubow

From Bernd-Peter Lange (Berlin):

‘After the Second World War, all German members of the National Socialist Party were required by the Allies to fill in a questionnaire (Meldebogen) for political examination. Bogoljubow’s was written in his own hand in September 1948 in the French zone of occupation where he was resident. It gives a great deal of information about, in particular, the years 1940-44, when he was in the service of Hans Frank, the Governor General of German-occupied Poland. He was employed firstly as a translator and interpreter (Ukrainian and Russian) in the Propaganda Department and then, for a longer period, as a chess instructor in German military hospitals in the Generalgouvernement and for chess-related tasks such as the design and distribution of a new chess set.

The denazification questionnaire gives precise details of his times of employment, payment received, dates of his party membership, and his political justification for having joined the Nazi Party.

A discussion of these texts – together with passages (some hitherto forgotten) related to Bogoljubow and chess matters in the vast service-diary of Hans Frank – has been prepared for the 1/2021 edition of the German-language magazine KARL, under the title “Bogoljubow im Generalgouvernement”. Later in 2021 there will be an expanded version in English, discussing Bogoljubow’s career from 1933 onwards.’

Our correspondent has forwarded us a PDF file which includes the questionnaire completed by Bogoljubow.

11860. The Immortal Game

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘A “Certificate of Arrival” at the port of Folkestone shows that Kieseritzky arrived there on 24 May 1851 (source: National Archives, HO 2/212, certificate no. 1067), this being a document which, with many others similar, is viewable on-line at Ancestry.com.

Under the heading “Name and country” is entered: “Mr Lionel Kieseritzki [sic] Russia”. The country from which he had last arrived was France and he had a passport from the French government. The certificate bears a good specimen of his signature: “L. Kieseritzky”.

As a result of Fabrizio Zavatarelli’s discovery in Baltische Schachblätter (reported in C.N. 11357), the Chess Notes feature article on the Immortal Game subsequently considered two dates, 25 and 26 May, as days when the celebrated game may have been contested. The fact that Kieseritzky did not arrive at Folkestone until 24 May now seems to detract somewhat from the argument for 25 May, as he would have needed to travel from Folkestone to London, settle into his hotel, meet Anderssen, etc., and there would have been less time to do these things if he had played the Immortal Game on 25 May (a Sunday). Conversely, the case for 26 May may be considered enhanced.

Another “Certificate of Arrival”, this time at the port of London, is dated 1 August 1851, and is signed “Lionel Kieseritzky” (National Archives, HO 2/223, certificate no. 5808).

No certificate of arrival in England prior to the 1851 tournament has so far been found for Anderssen.’

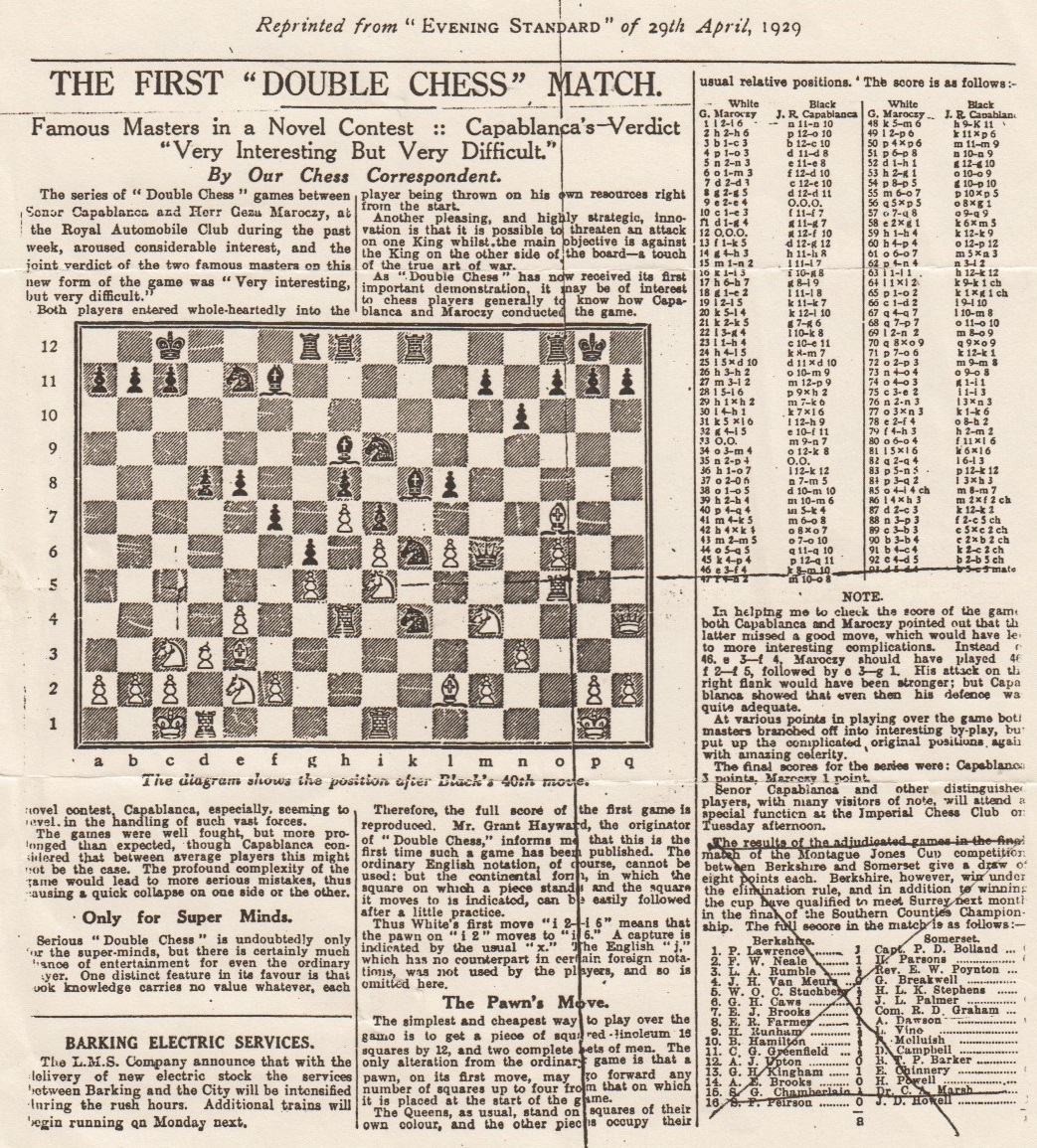

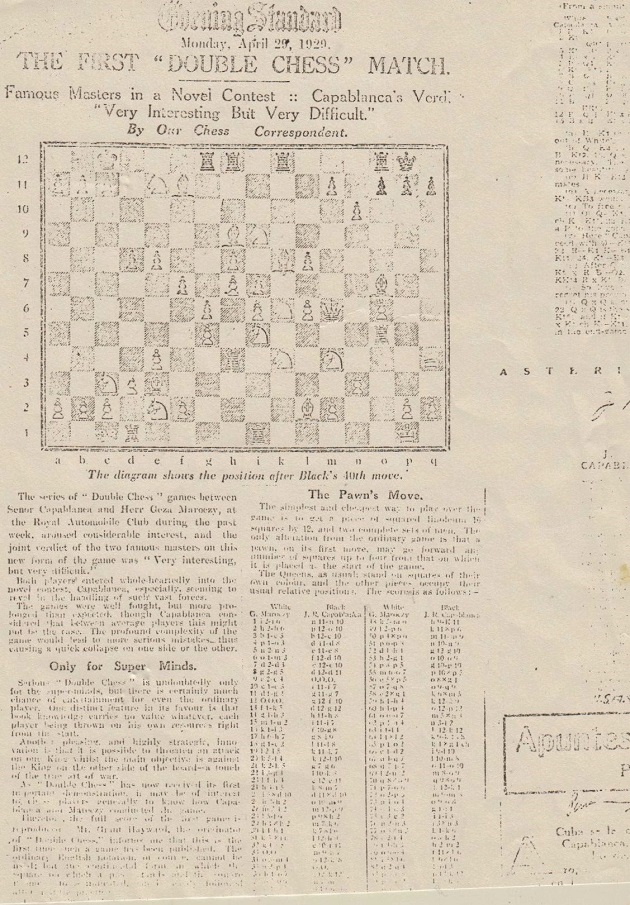

11861. Double chess (C.N.s 5619 & 10446)

From our archives:

The article’s exact original appearance in the Evening Standard newspaper is not currently to hand.

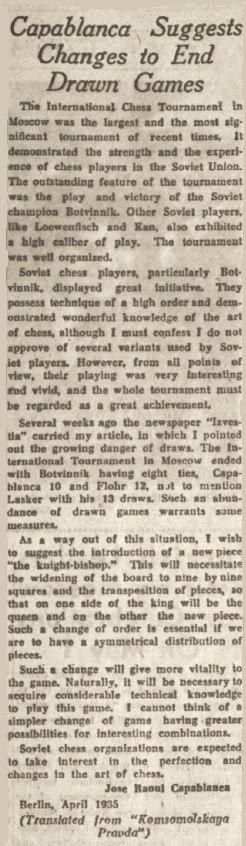

On the subject of Capablanca’s proposals for different forms of chess, Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) has found the following on page 3 of the Moscow Daily News, 23 April 1935 (‘Translated from Komsomolskaya Pravda’):

11862. Manuel Márquez Sterling (C.N. 5908)

Yandy Rojas Barrios (Cárdenas, Cuba) has forwarded this picture of Manuel Márquez Sterling from page 364 of El Fígaro, 18 June 1909:

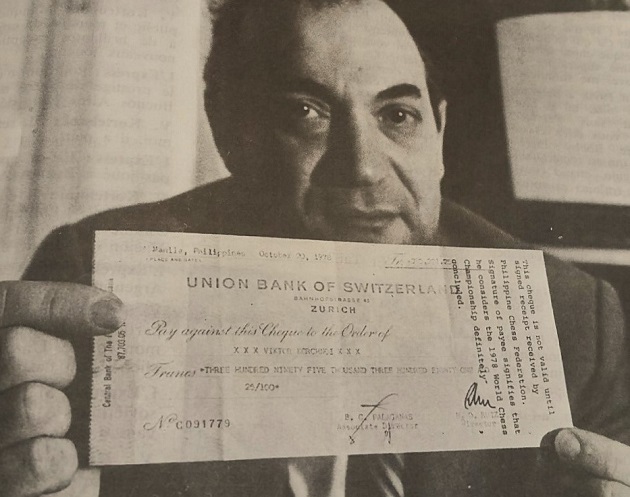

11863. The 1978 world championship match

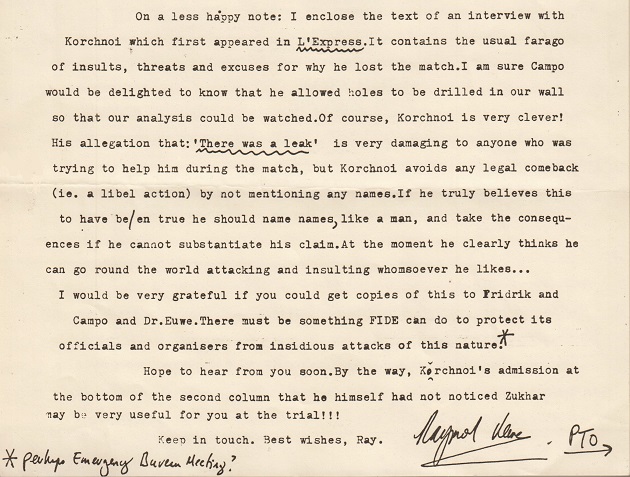

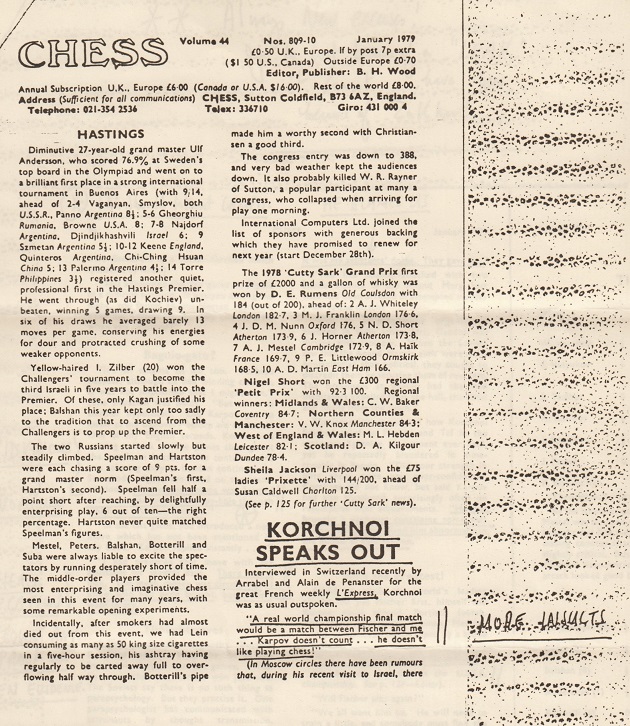

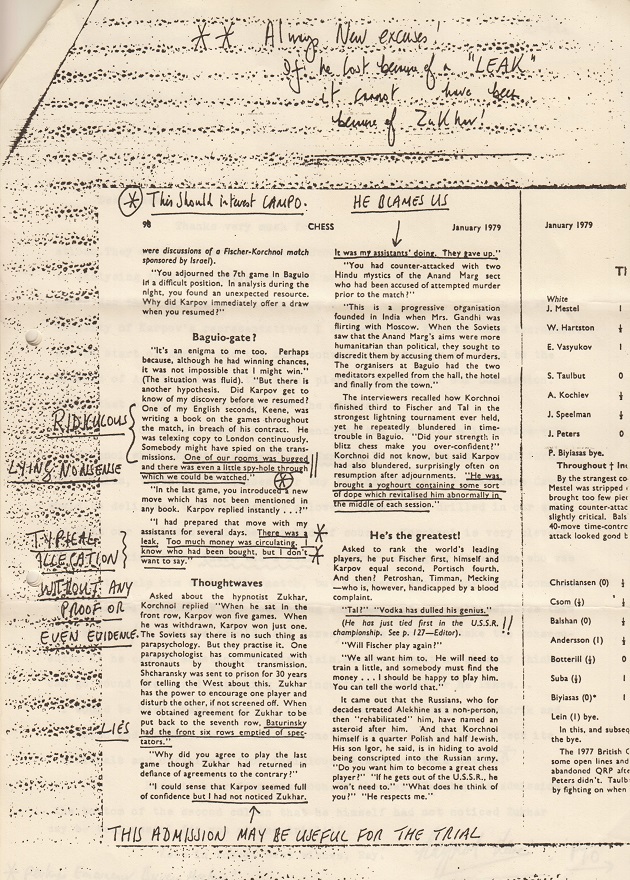

On pages 54-56 of the 23 December 1978 issue of L’Express Victor Korchnoi gave an interview to Arrabal and Alain de Pananster concerning, primarily, his recent world title match against Karpov in Baguio City. The heading was ‘Kortchnoï: Un espion m’a fait perdre’, but the alleged spy was left unnamed (Korchnoi: ‘Je sais qui a été acheté, mais je ne veux pas le dire’). The lack of rigour throughout the questions and answers is such that we show here, in passing, just one brief exchange, from page 55 (where the above photograph also appeared):

‘L’Express: Y a-t-il une relation entre les échecs et le mysticisme? Autrefois, Steinitz prétendait jouer contre Dieu ...

V. Kortchnoï: Le recours à un être suprême est compréhensible. Karpov est athée. Un domaine lui échappe.’

An English translation of relatively brief extracts from the interview was published on pages 97-98 of CHESS, January 1979, under the title ‘Korchnoi Speaks Out’. It was reproduced, with much valuable additional material, in the 2013 article by Justin Horton ‘What Jean Stean had seen’.

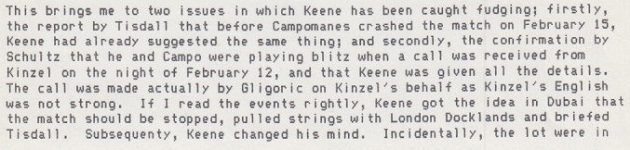

Raymond Keene was specifically mentioned only once in L’Express, with his surname misspelt. As regards the English-language version of the interview, below is his communication of 23 February 1979 to the FIDE General Secretary, Ineke Bakker:

The only living person whom we would trust for a truthful first-hand account of what happened in Baguio City is Michael Stean.

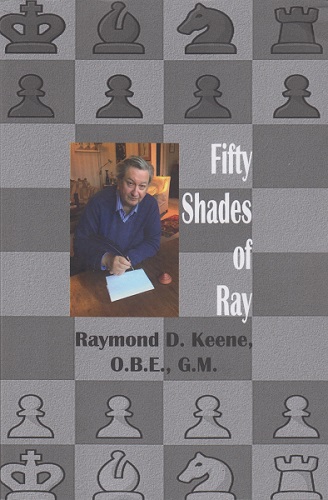

11864. Incorrigible

On 18 May 2021 we added to Cuttings the remark below concerning a book compilation of material by Raymond Keene most recently published in The Article and in the BCM (though often in other unnamed places previously):

We skimmed the chess content of Fifty Shades of Ray for about an hour, ignoring all the recycling and re-recycling of games. With a tally of over 100 errors, misspellings, typos and inconsistencies we gave up in disgust.

Now, a few days later, a second reluctant examination has revealed, unsurprisingly, a vastly higher tally.

It is a calamitous book, even by Raymond Keene’s standards. A dozen or so proper names are spelt two or more ways, and in some cases on the same page (e.g. Loewenthal and Löwenthal on page 32, and Lowenthal on page 44); page 42 has both Vinyoles and Vinoles, concerning a game whose first note says that White ‘could have plated 6. Bx7+’. General editing, lay-out, punctuation, italicization, etc. are a fiasco. Already on pages ix-xii, the list of contents and the list of games have dozens of mistakes. Elsewhere there is the amateurish spectacle of a comma at the beginning of a line, and a line consisting of some 65 letters with no spaces between words. On page 128 Raymond Keene professes an academic knowledge of French, but nearly 20 French words and names are rendered inaccurately in the book. The only picture, occupying half of page 266, is the top part of a tournament crosstable; it is illegible.

Some sections gave us the impression of being the first person ever to read, or even skim, them in their current form, despite Raymond Keene’s affirmation in the Introduction that the columns have been edited (by C.J. de Mooi) and proofread (by Julian Hardinge). The Introduction also expresses thanks to four family members ‘for invaluable assistance in honing the original contributions from which this volume is composed’. Goodness knows what the unhoned versions looked like.

C.J. de Mooi’s syrupy Foreword could easily be picked apart, but here we quote just one paragraph:

‘... that old enemy time moves inexorably forward and the old are usurped by the young. After over three decades as the chess correspondent for both The Times and The Spectator he was unceremoniously replaced.’

This echoes Raymond Keene’s own untruthful and ungrammatical words on his Twitter page, 31 July 2020 (quoted in full in Cuttings):

‘I am 72. Last year, at the age of 71, both The Spectator and The Times fired me after respectively serving for 42 years and 34 years without missing a single column ...’

At present, therefore, it is The Article and the BCM that showcase, so to speak, his output, although large swathes of the output are input from past writings, copy-pasted with no attempt to rectify their obvious defects, even when they have been pointed out publicly.

Our feature article The Immortal Game (Anderssen v Kieseritzky) shows how, over the years, Raymond Keene has rehashed various factual blunders about the 1851 brilliancy. Far from taking account of chess historians’ investigations, discoveries, corrections and conclusions, Fifty Shades of Ray remains incompetent over the most basic matters: yet again, for instance, the players are named as ‘Adolph’ Anderssen (also ‘Andersen’ on the same page, where we find too ‘the Ruy Lopex’) and ‘Kieseritsky’. The game, incidentally, features a ‘gradiose’ combination.

The scrappy sections on Alekhine and the Nazi articles are illogical and self-contradictory. Raymond Keene, the antithesis of a chess historian, seldom offers sources, preferring bare assertion as if he, of all people, can be taken on trust. Page 109 has categorical statements about how exactly Alekhine died (which nobody knows) and when he died (‘on the evening of March 25, 1946’). As shown in our feature article on the subject, Alekhine’s death had been reported worldwide the previous day.

Sloppiness pervades Fifty Shades of Ray with, even, mistakes and inconsistencies in the names of Raymond Keene’s present publisher, present employer, former publisher and former newspaper; and in the titles of a book which he co-authored and one to which he contributed. To be liked by him is a burden carrying no guarantee of a correctly printed name, as Dominic O’Brien will find on page 207 (two mentions, both with typesetting mishaps).

Leaden repetition of titles is embarrassingly frequent (see, for instance, how Nigel Short has the misfortune of being referred to), and never more embarrassing or frequent than when Raymond Keene is presenting himself:

- Front cover: Raymond D. Keene, O.B.E., G.M.;

- Spine: Raymond D. Keene, O.B.E., G.M.;

- Frontispiece caption: Raymond D Keene OBE;

- Title page: Raymond D Keene OBE;

- Imprint page: Raymond D. Keene, OBE;

- Page vii: Ray Keene OBE;

- Page x: Raymond D Keene, OBE;

- Page x: Raymond D. Keene, OBE;

- Page 288: Raymond D. Keene, OBE;

- Page 289: Raymond D. Keene, OBE.;

- Back cover: Grandmaster Ray Keene OBE.

11865. Pomar and Franco

Concerning meetings between Arturo Pomar and General Franco, Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) draws attention to a photograph of another encounter (Madrid, 15 July 1959) in the archives of ABC.

11866. D.J. Morgan and Newsflash

In his Preface to Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984) G.H. Diggle mentioned that until 1974 the British Chess Federation publication Newsflash had a column by D.J. Morgan. Does any reader have a run of that column?

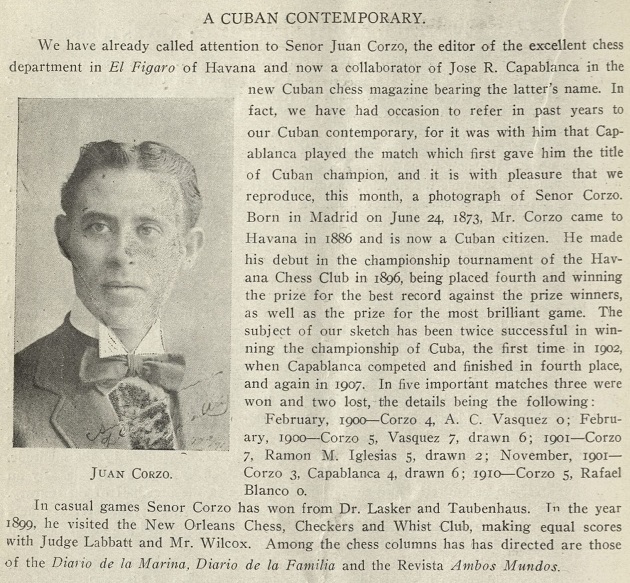

11867. Janowsky v Corzo

Yandy Rojas Barrios (Cárdenas, Cuba) notes a photograph of Janowsky in play against Juan Corzo (Havana, 1913) in Capablanca-Magazine, 28 February 1913, page 45:

The original in the Cuban periodical is difficult to reproduce well, but the above good scan has been provided by the Cleveland Public Library.

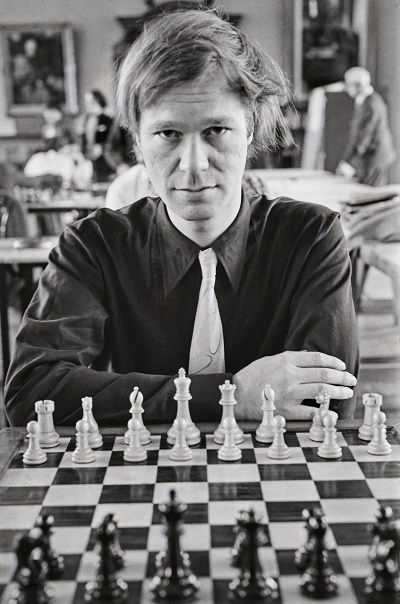

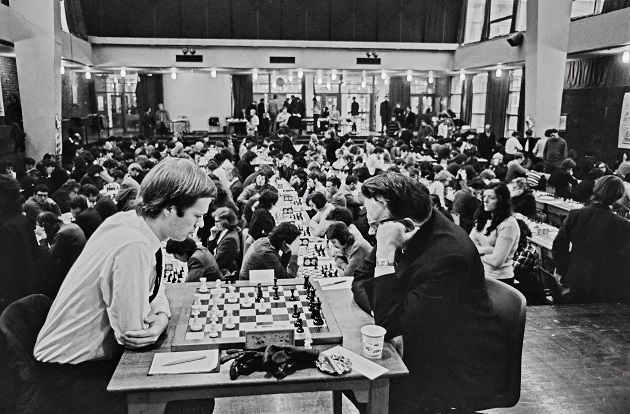

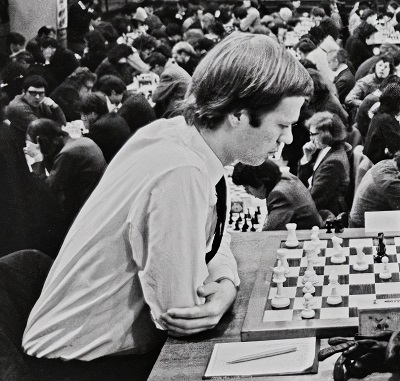

11868. Brian Eley (C.N. 9034)

From page 318 of the September 1972 BCM, following Eley’s victory in the British Championship:

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) provides two further photographs, courtesy of the Hulton Archive:

The Eley v Pachman game shown above was discussed in C.N.s 7663 and 10988.

11869. W. Hatton Ward (C.N. 5653)

C.N. 5653 drew attention to discrepancies in the forename (William or Walter?) and surname (hyphenated or not?) of the organizer of London, 1946, to whom Alekhine wrote a lengthy open letter after his invitation to the tournament was withdrawn.

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘The death of “W. Hatton Ward”, “well-known chess editor and organiser”, was announced in the Staffordshire Advertiser, 25 November 1950, page 6.

According to the National Probate Calendar, Walter Hatton Ward, of Mount Pleasant, 71 Wellington Street, Hertford, died on 14 October 1950; probate was granted in London on 12 December to Walter Henry Hatton Ward, eastern electricity board district manager, the effects amounting to £1,197 17s. 11d.

The General Register Office’s index of deaths contains an entry in the quarter ending 31 December 1950 for Walter H. Ward, in the registration district of Hertford (volume 4b, page 77), his age being given as 76.

In the above official sources his name was not hyphenated.’

11870. Staunton and London, 1851

What is the fairest brief description of Howard Staunton’s organizational involvement in the London, 1851 tournament?

We put the matter to John Townsend, who responds:

‘“Played a leading role in” would be my choice.

However, there were limits to his involvement and responsibility. The Committee included several aristocrats, who could be infinitely more powerful than he was.

Rivalry existed between the London Chess Club and the St George’s and, where there was conflict, Staunton has been blamed. However, his was only one voice on the Committee – albeit an important one – so he was not solely responsible for decisions taken. Neither was Staunton the Secretary of the Committee. That was Miles Gerald Keon, and it was he who dealt with correspondence on behalf of the Committee.’

11871. The Immortal Game

Regarding the Anderssen v Kieseritzky brilliancy, it will be appreciated if readers can trace other appearances of the game in nineteenth-century primary sources, and not least publications in German and French.

11872. William Hartston

Further to our recent feature article on him, William Hartston (Cambridge, England) informs us that he considers his best work to be Sloths! (London, 2018), later issued in a paperback edition with no exclamation mark in the title.

11873. Nicolas Rossolimo

A fine portrait of Rossolimo (Hastings, 1949), courtesy of the Hulton Archive:

11874. Simultaneous displays

C.N.s 594 and 4492 (see too pages 237-238 of Chess Explorations) mentioned Staunton’s aversion to simultaneous displays, as expressed on page 341 of the Illustrated London News, 14 April 1866:

The difficulty in establishing Morphy’s non-blindfold simultaneous activities was referred to in C.N. 10423.

11875. Charles Jaffe

Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) informs us that Moshe Roytman has found on the online database of Jewish publications in the National Library of Israel that in 1906 Charles Jaffe launched a Yiddish-language chess periodical, דער אידישער שאך-זשורנאל (‘The Jewish Chess Journal’). The second page listed the contents:

1. Foreword;

2. Recommendations for the new journal from Em. Lasker and M. Ginsburg;

3. A biography of Professor Rice;

4. Ibn Ezra’s ‘Song of Chess’;

5. Chess and how to play it (the laws of the game);

6. The opening: a brief analysis of two lines in the King’s Gambit;

7. Marshall v von Scheve (Rice Gambit game, with notes by The Field and by Jaffe);

8. The chess world. News and announcements. In particular, an obituary of Max Judd;

9. Em. Lasker v Pillsbury with notes by Jaffe;

10. Problems and endgame department.

Noting the stamp of the Cleveland Public Library on the second page, we have obtained the Library’s permission to show the full issue here as a PDF file.

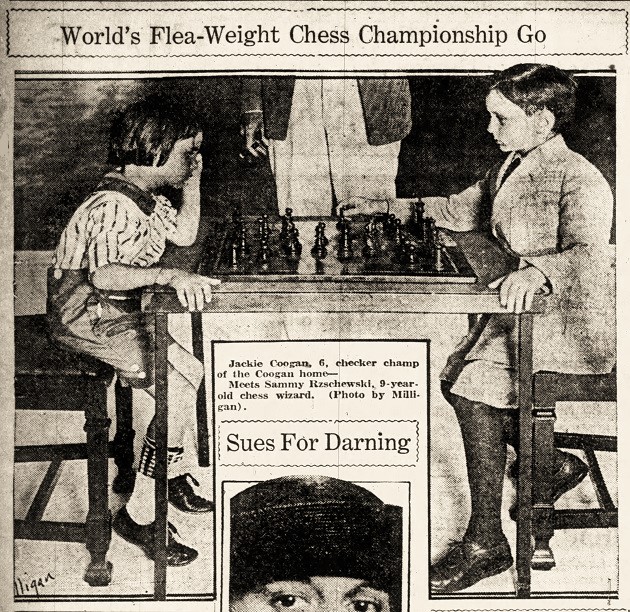

11876. Jackie Coogan and Sammy Reshevsky

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) sends the photograph referred to in C.N. 7784:

He also provides this cutting from page 8 of the Los Angeles Record, 18 July 1921:

Earlier that year, Jackie Coogan became famous for playing the title role in the Charlie Chaplin film The Kid.

The above pictures are being added to The Chess Prodigy Samuel Reshevsky.

11877. D.J. Morgan and Newsflash (C.N. 11866)

Answering the question in C.N. 11866, Alan Slomson (Leeds, England) writes that the columns of D.J. Morgan in Newsflash ran from issue 25 (30 November 1968) to issue 88 (1 March 1974). They covered all the British Championships from Hastings, 1904 to Eastbourne, 1973, giving just the result, a few comments and one game (material based on what the relevant year’s BCM had published).

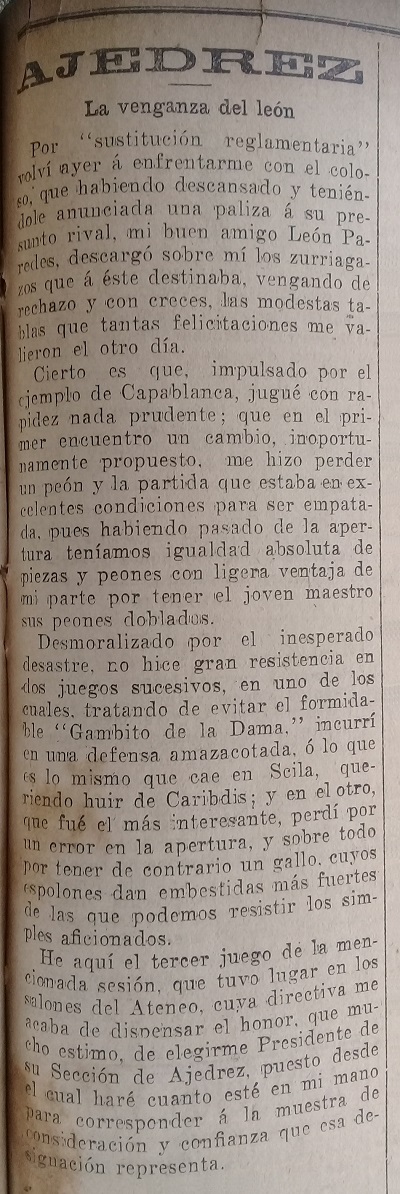

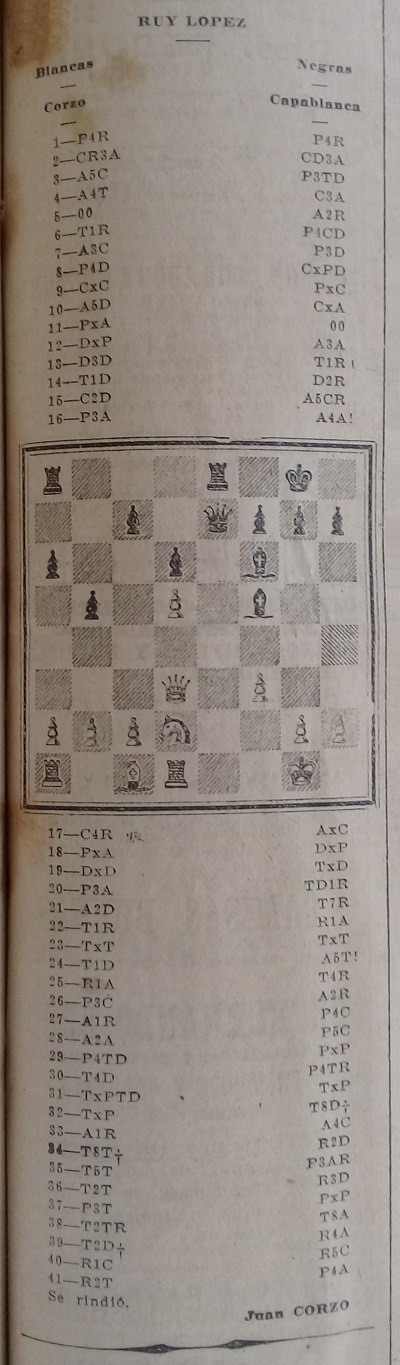

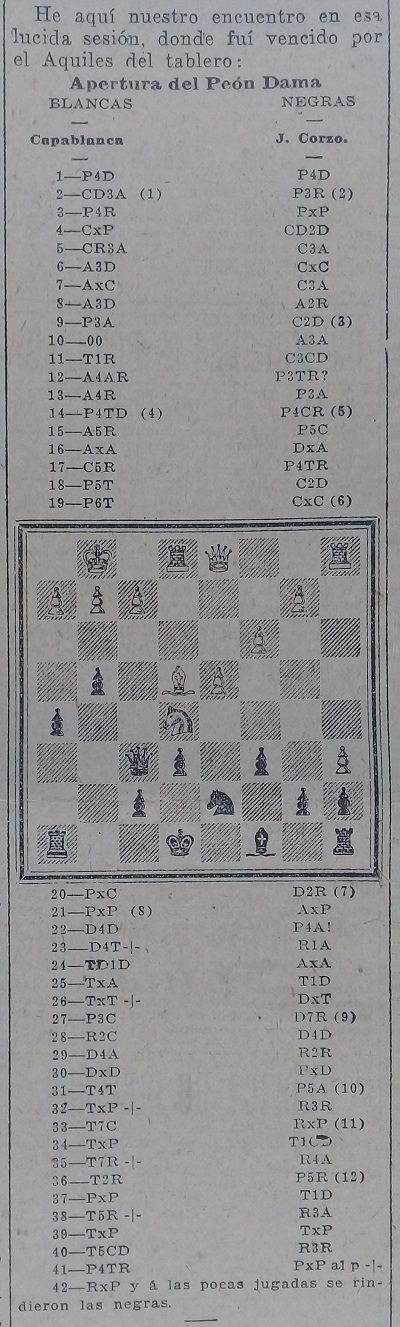

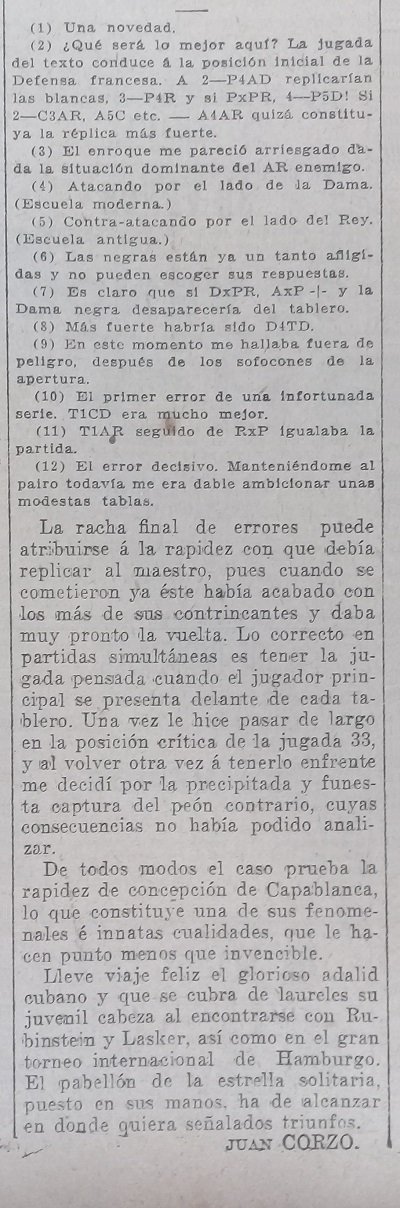

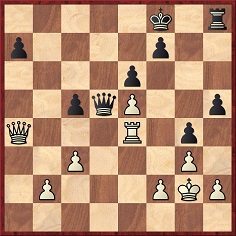

11878. Capablanca in Havana, 1909

From Yandy Rojas Barrios (Cárdenas, Cuba):

‘After his match against F.J. Marshall in the United States, Capablanca resided in Havana from July to September 1909. During his stay, he played five games against Juan Corzo, one against Rafael Blanco and one against René Portela. He also played his first blindfold game against three opponents in consultation and gave one simultaneous exhibition (+23 –1 =1).

Concerning the five games against Corzo, Game 1, played on 21 July, was drawn. It was published on page 5 of the evening edition of the Diario de la Marina, 22 July 1909 and was included on pages 37-38 of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975).

On 23 July, Games 2, 3 and 4 were played.

Game 2, won by Capablanca, appeared on page 3 of La Discusión, 24 July 1909, as cited on page 20 of your book on Capablanca. You refer to it as the first of the games played on 23 July, which is correct.

Game 3 was published in neither the Diario de la Marina nor La Discusión. Corzo merely made the following comment on page 5 of the evening edition of the Diario de la Marina, 24 July 1909: “Demoralized by the unexpected disaster [in Game 2], I did not put up much resistance in two successive games, in one of which, trying to avoid the formidable Queen’s Gambit, I faced an arduous defensive task ...”:

The game-score can be found in volume one of Secrets of the Russian Chess Masters by L. Alburt and L. Parr (New York, 1997). See, in particular, pages 101-102. (Acknowledgement: the Cleveland Public Library.) The book dated the game 23 July, but no other information was supplied, about either the occasion or about how the moves were obtained. Further details will be welcome. It is the only game in the series in which Capablanca was White: 1 d4 d6 2 Nc3 Nd7 3 d5 e5 4 dxe6 fxe6 5 Nf3 Ndf6 6 e4 e5 7 Bc4 Bg4 8 h3 Bh5 9 g4 Bf7 10 Bxf7+ Kxf7 11 Ng5+ Ke8 12 Be3 c6 13 Qd3 Ne7 14 O-O-O Ng6 15 Ne6 Qd7 16 Nxf8 Rxf8 17 Qxd6 Qxd6 18 Rxd6 Ke7 19 Rhd1 Kf7 20 g5 Nh5 21 Rd7+ Kg8 22 Rxb7 Rf3 23 Rxa7 Raf8 24 a4 Rxh3 25 a5 Ngf4 and Black resigned.

I am pleased to report that I have found Game 4, played on 23 July, on page 5 of the evening edition of the Diario de la Marina, 24 July 1909:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 d6 8 d4 Nxd4 9 Nxd4 exd4 10 Bd5 Nxd5 11 exd5 O-O 12 Qxd4 Bf6 13 Qd3 Re8 14 Rd1 Qe7 15 Nd2 Bg4 16 f3 Bf5 17 Ne4 Bxe4 18 fxe4 Qxe4 19 Qxe4 Rxe4 20 c3 Rae8 21 Bd2 Re2 22 Re1 Kf8 23 Rxe2 Rxe2 24 Rd1 Bh4 25 Kf1 Re5 26 g3 Be7 27 Be1 g5 28 Bf2 g4

29 a4 bxa4 30 Rd4 h5 31 Rxa4 Rxd5 32 Rxa6 Rd1+ 33 Be1 Bg5 34 Ra8+ Ke7 35 Ra5 f6 (From this point the score in the Cuban newspaper is evidently wrong. There follows here a proposed reconstruction.) 36 b4 Ke6 37 Ra2 Rb1 38 h3 gxh3 39 Rh2 Rc1 40 Re2 + Kf5 41 Kg1 Kg4 42 Kh2 f5 43 White resigns.

Game 5, played on 31 July, was drawn. It was published on page 5 of the evening edition of the Diario de la Marina, 2 August 1909 and is on pages 38-39 of The Unknown Capablanca. Hooper and Brandreth referred to it as “the second game” because they were aware of only two games; The Unknown Capablanca even speculated that they were two thematic games, given that they had the same opening.

Capablanca’s games against Blanco and Portela, played on 25 and 27 July respectively, are on page 20 of your book, from La Discusión. You note that the newspaper garbled the final moves of the Blanco game, and I think that the likely finish was 29 Qxe1 Qxg4 30 Qxe4 Qf3+ 31 Qxf3 Nxf3 32 White resigns.

The blindfold game played by Capablanca on 22 August against Corzo, Blanco and Rensolí, which you also gave on page 20 of your book from La Discusión, was published too on page 5 of the evening edition of the Diario de la Marina, 22 August 1909.

As regards the simultaneous display by Capablanca on 14 September, some details are available: “The session began at nine o’clock [at night] and lasted approximately 2½ hours. The result was one lost game by the inadvertent touching of a piece; another game was drawn and the rest were won by the Cuban champion” (Diario de la Marina, morning edition, 15 September 1909, page 9).

Capablanca’s lost game was not published in the Diario de la Marina or in La Discusión. The only draw, against José Antonio Jover, was given on page 5 of the evening edition of the Diario de la Marina, 15 September 1909. Capablanca was White: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 d6 4 O-O Bd7 5 Re1 a6 6 Ba4 b5 7 Bb3 f5 8 exf5 Bxf5 9 d4 Nf6 10 dxe5 dxe5 11 Qxd8+ Rxd8 12 Ng5 Rd7 13 c3 Na5 14 Bd1 h6 15 Nf3 Bd6 16 Nxe5 Re7 17 Nf3 Rxe1+ 18 Nxe1 O-O 19 a4 b4 20 Bd2 c5 21 cxb4 cxb4 22 Bc2 Bxc2 23 Nxc2 Rc8 24 Ne1 Nb3 25 Ra2 Nc1 26 Ra1 Nb3 Drawn.

I have found that Capablanca’s victory over Juan Corzo in that 14 September simultaneous display was published on page 9 of the morning edition of the Diario de la Marina, 18 September 1909:

1 d4 d5 2 Nc3 e6 3 e4 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Nd7 5 Nf3 Ngf6 6 Bd3 Nxe4 7 Bxe4 Nf6 8 Bd3 Be7 9 c3 Nd7 10 O-O Bf6 11 Re1 Nb6 12 Bf4 h6 13 Be4 c6 14 a4 g5 15 Be5 g4 16 Bxf6 Qxf6 17 Ne5 h5 18 a5 Nd7 19 a6 Nxe5 20 dxe5 Qe7 21 axb7 Bxb7 22 Qd4 c5 23 Qa4+ Kf8 24 Rad1 Bxe4 25 Rxe4 Rd8 26 Rxd8+ Qxd8 27 g3 Qd2 28 Kg2 Qd5

29 Qc4 Ke7 30 Qxd5 exd5 31 Ra4 c4 32 Rxa7+ Ke6 33 Rb7 Kxe5 34 Rxf7 Rb8 35 Re7+ Kf5 36 Re2 d4 37 cxd4 Rd8 38 Re5+ Kf6 39 Rxh5 Rxd4 40 Rb5 Ke6 41 h4 gxh3+ 42 Kxh3 “and after a few moves Black resigned”.’

11879. William Winter

Terry Hart (Cambridge, England) asks what became of the papers of William Winter, including the manuscript of his memoirs (see C.N.s 1197 and 1240 in our feature article on him).

The above photograph of William Winter is shown courtesy of the Universal History Archive/Universal History Group. C.N. 6121 had a less good version, the frontispiece to the 1936 edition of his book Chess for Match Players.

11880. Hungarian chess photographs

The MTVA Archívum has a fine selection of chess-related photographs.

11881. Cuban chessplayers

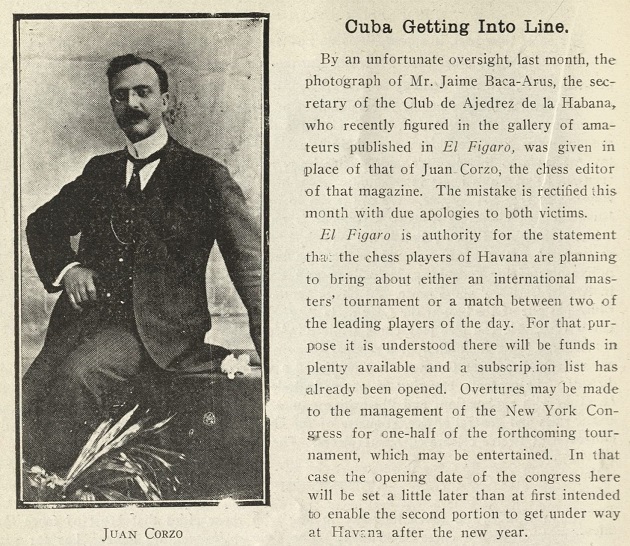

From page 106 of the May 1912 American Chess Bulletin:

The photograph is not in our feature article on Juan Corzo because it is a case of mistaken identity, as was pointed out on page 136 of the June 1912 edition of the Bulletin:

The above scans have been provided by the Cleveland Public Library.

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has restored the Jaime Baca-Arús photograph:

11882. The Capablanca Project

The Capablanca Project has just been launched by Olimpiu G. Urcan.

As an example of photographs for which better versions are sought, he sends us the following from page 30 of TIME, 24 March 1924:

11883. Where Staunton lived (C.N.s 3979 & 3984)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘Howard Staunton was commemorated in 1999 by a blue plaque at 117 Lansdowne Road, Notting Hill, London:

“HOWARD STAUNTON 1810-1874

British World Chess Champion

lived here 1871-1874”I believe the dates contain an inaccuracy in that he did not live there until 1872. In my book Notes on the Life of Howard Staunton, published in 2011, his place of residence between 14 February 1872 and 1 April 1872 is clearly traced on pages 153-154 through the contents of four letters which are cited:

- 14 February 1872: written from 27 Chilworth Street;

- 13 March 1872: written from 27 Chilworth Street: he is “in treaty for a house near to St John’s Church, Notting Hill”;

- 15 March 1872: written from 27 Chilworth Street: he extends an invitation to his new home when he moves into it;

- 1 April 1872: written from 117 Lansdowne Road: he moved in “last Saturday”.

Consequently, Staunton did not reside at 117 Lansdowne Road until Saturday, 30 March 1872.

The above-mentioned English Heritage webpage states:

“Staunton’s plaque was therefore erected at 117 Lansdowne Road, where he lived from late 1871 until spring 1874, shortly before his death.”

In the light of the four letters mentioned above, it would be interesting to know what evidence exists for the “late 1871” part of this statement and for “1871” on the plaque.’

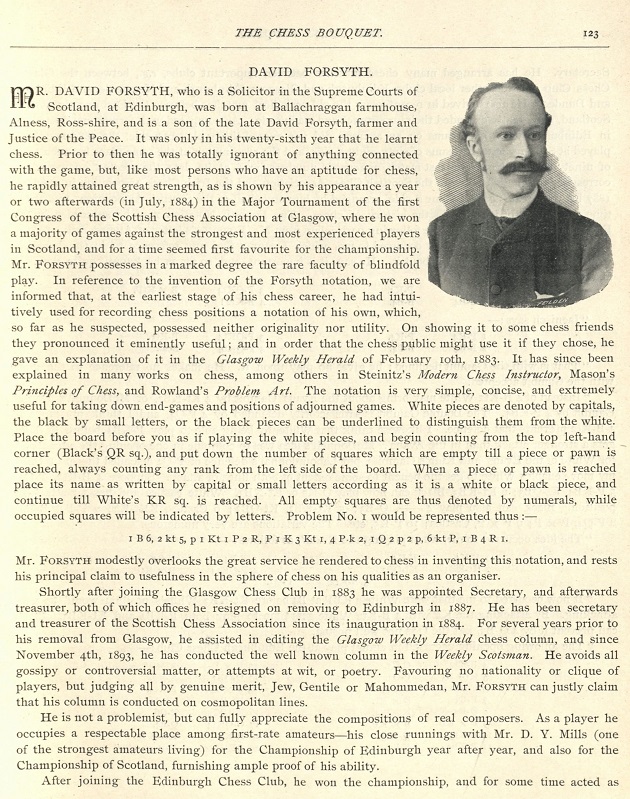

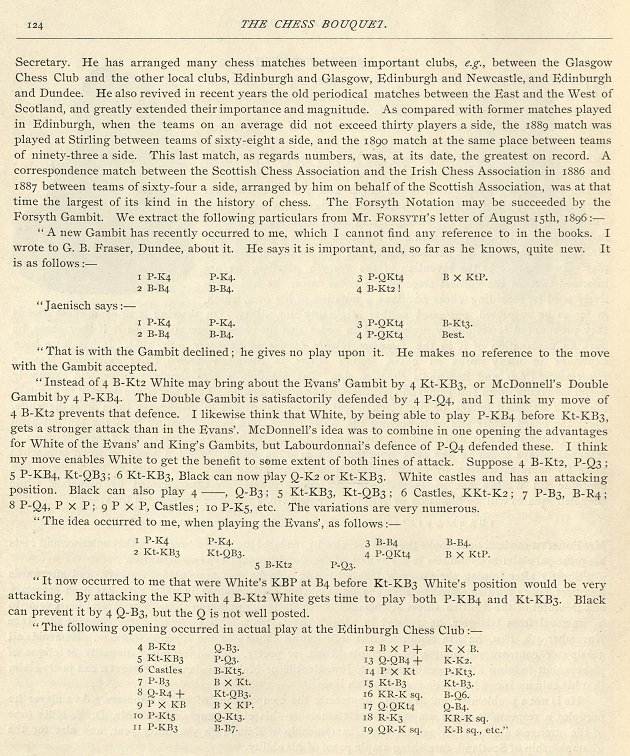

11884. A forgotten figure

This picture of David Forsyth (1854-1909) was shown in C.N. 5051 from page 123 of The Chess Bouquet by F.R. Gittins (London, 1897). The full entry is below, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library:

11885. Notation (Hebrew)

Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) writes:

‘Your recent feature article on chess notation prompts me to add some curiosities regarding texts in Hebrew. The revival of Hebrew in chess faced two problems. The first was the establishment of chess terms and whether to follow the continental or English terms, e.g. whether to speak of a malka (queen) or a gvira (dame), or a chayal (soldier, i.e., pawn), ragli (foot soldier), ikar (Bauer), etc. Generally, the English terms prevailed, with one exception: the diagonally-moving piece was, from the outset, called a ratz, runner (i.e. Läufer).

The second issue is more interesting. It seems that the descriptive notation was never used in Hebrew chess literature, which left the problem of how to translate the names of the squares in algebraic notation. The ranks, being numerical, presented no problem, but how should the files be named in Hebrew, a language written from right to left?

The most natural way would be to name the a-file the aleph (the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet) file, the b-file the bet (second letter) file, etc. Strange to say, this was not attempted until Shaul Hon did so in his short-lived chess magazine in 1946. The reason, Hon notes, is that it requires the order of the files to go the “wrong” way, from left to right. An attempt was made to name the files from right to left, aleph denoting the h-file, beth the g-file, etc., as noted on a Jewish Chess History page. Confusingly, this made the notation look like a mirror-image (the Ruy López opening seemed to be 1 d4 d5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Bg5), and it was abandoned almost immediately.

Thus until 1946, a curious hybrid existed: chess notation used the Hebrew names – or, rather, initials – for the pieces but the non-Hebrew names for the squares. This gave rise to a further question: in which direction should the text be written? Both possibilities have been tried: right to left and left to right.’

11886. Blackburne photographs

The above photograph of J.H. Blackburne is owned by Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England), who presented it in C.N. 4791.

A slightly different shot from page 20 of the 18 December 1921 edition of the Sunday Illustrated (the London publication of Horatio Bottomley, the Independent MP for Hackney South):

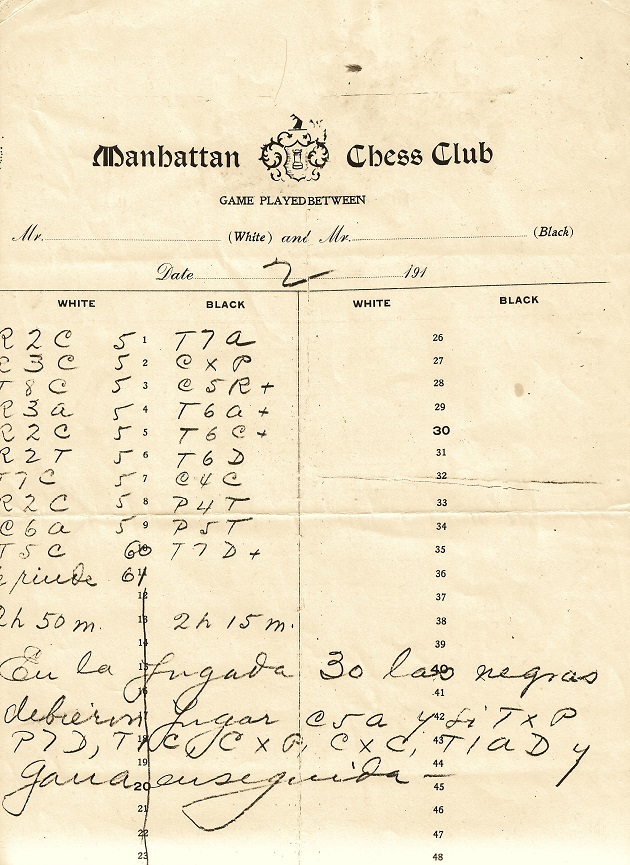

11887. Coldwell v Marshall

C.N. 1981 (see page 68 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) gave this game won by F.J. Marshall:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 O-O d6 5 c3 Bg4 6 d3 h6 7 Be3 Bb6 8 Nbd2 Nf6 9 Qc2 Bxf3 10 Nxf3 Ng4 11 Rae1 Ne7 12 h3 Nf6 13 Qb3 O-O 14 Bxb6 axb6 15 d4 Ng6 16 Qc2 Qe7 17 g3 Qd7 18 Kg2 Qc6 19 Qe2 Qd7 20 Rd1 Nh5

21 Nxe5 Ngf4+ 22 gxf4 Nxf4+ 23 Kf3

23...Qxh3+ 24 Kxf4 g5 mate.

Our source, page 82 of the Chess Amateur, December 1907, described it as ‘a remarkably pretty ending’ but gave no details of the occasion or any information about White, apart from his surname, Coldwell.

Now, Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) proposes as a working hypothesis that it was an offhand or simultaneous game played in London in April 1905 against P.H. Coldwell, on the basis of these considerations:

No chessplayer named Coldwell, or any close variant, has been found in the United States or Canada during the period 1893-1907. P.H. Coldwell was a member of the Hampstead Chess Club, as mentioned, for instance, on pages 151-153 of the April 1905 BCM. A game won by P. Coldwell against Louisa Fagan in the Hampstead Chess Club tourney in 1906 was published on page 2 of the Bridlington Free Press, 7 December 1906.

Marshall went to London in 1899, 1902, 1903 and 1905. As regards the last of these visits, he departed for London from Mannheim on 11 April 1905 (Deutsche Schachzeitung, June 1905, page 156). The following day he gave a simultaneous display at the City of London Chess Club, with the result +4 –9 =7 (Daily News, 20 April 1905, page 11); in an exhibition at the Criterion (Metropolitan Chess Club) on 26 April 1905 he scored +14 –2 =4, as reported, inter alia, on page 6 of the Hampstead & Highgate Express, 6 May 1905. Page 7 of the Woolwich Gazette, 5 May 1905 stated that ‘Marshall has been a regular attendant at London chess resorts during the last week’. In early May, he departed for Hamburg (Deutsche Schachzeitung, June 1905, page 186).

11888. Capablanca’s lectures (C.N. 8693)

Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) asks whether the exact history of Capablanca’s ‘lectures’ book, published in English in the 1960s, can be pieced together.

11889. William Winter (C.N. 11879)

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘I have obtained a copy of William Winter’s will, dated 11 June 1954. The main legatee was Evelyn Ethel Olorenshaw, but Clause 3 stated that he bequeathed to David V. Hooper (94 High Street, Reigate) “all my chess manuscripts and publications and any royalties accrued or to accrue due in respect thereof in the confident knowledge that he will do everything necessary or proper to perpetuate my name”.

The National Probate Calendar states that Winter died on 17 December 1955. His address was given as 145 King Henry’s Road, Hampstead, London. The will was proved in London on 5 March 1956, the effects amounting to £4,819 6s. 8d.

David Hooper’s will, made on 19 April 1986 and proved on 24 June 1998, stated that he bequeathed all his chess-related material and rights to Kenneth Whyld. The latter left his chess collection to the Musée suisse du jeu, La Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland.’

11890. Kuhn v Gajdos

In C.N. 3754 a correspondent gave this 1964 game between P.N. Lee and D.J. Mabbs: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 d6 8 c3 Na5 9 Bc2 c5 10 h3 Qc7 11 d4 Nc6 12 Nbd2 g5 13 a4 Rb8 14 dxc5 dxc5 15 Nf1 g4 16 hxg4 Bxg4 17 Ne3 Rg8 18 axb5 axb5 19 Qe2 Qc8 20 Nd5 Nh5 21 Qe3 Bh3 22 Nxe7 Rxg2+ 23 Kf1 Qg4 24 Ke2 Nd4+ 25 cxd4 exd4 26 Qh6 Rxf2+ 27 Kd3 Qxf3+ 28 Be3 Bf1+ 29 Rxf1 Qe2 mate.

Alan Smith (Stockport, England) draws attention to the following:

K. Kuhn – J. Gajdos

Budapest, 1912

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 d6 8 c3 Na5 9 Bc2 c5 10 d3 Qc7 11 h3 Nc6 12 Nbd2 g5 13 Nxg5 Rg8 14 Nf1 h6 15 Nf3 Bxh3 16 Kh2 Ng4+ 17 Kg1 Bxg2 18 Ng3 Bh3 19 Nh2 Nxh2 20 Kxh2 Bg4 21 f3 Be6 22 Be3 O-O-O 23 a4 Bh4 24 Bf2 Qe7 25 axb5 Bxg3+ 26 Bxg3 Qg5 27 Rg1 Qh5+ 28 Kg2 Rxg3+ 29 Kxg3 Rg8+ 30 Kf2 Qh2+ 31 Ke3

31...Nd4 32 Rxg8+ Kd7 33 Rc1 f5 34 Rg7+ Ke8 35 White resigns.

Sources: Amsterdammer weekblad voor Nederland, 2 March 1913, page 11, and the Sydney Sunday Times, 16 March 1913, page 27.

11891. A strange manoeuvre (C.N. 2114)

C.N. 2114 showed this position (after 30 Re1-b1) in the game Kupchik v Capablanca, New York, 24 and 29 July 1913:

We mentioned that on his score-sheet Capablanca wrote that instead of 30...Na4 he should have played 30...Nc4, and if 31 Rxb5 d2 32 Rb1 Nxe5 33 Nxe5 Rc8, and Black wins at once.

On page 32 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) commented:

‘Very interesting. White’s most stubborn continuation at the end of Capablanca’s variation would be 34 Kg2 Rc1 35 Rb8+ Kh7 36 Nxf7, but Black wins after 36...g6 37 hxg6+ Kxg6 38 Ne5+ Kg7 39 Rb7+ Kf8, since the king can ultimately escape from perpetual check.’

The relevant page of Capablanca’s score-sheet:

11892. A masters’ association

Richard Forster writes:

‘In a letter to Ilya Maizelis (New York, 7 July 1939), Emanuel Lasker wrote:“Der Vereinigung der Schachmeister, deren Mitglieder Botwinnik, Alekhin, Capablanca, Euwe, Flohr, Fine, Reszhewski, Keres sind, bin ich nun angeschlossen und hoffe, dass sie etwas zur Förderung des Meisterschachs beitragen wird.”

Are any details known about this attempt to form a masters’ association, perhaps in conjunction with the AVRO, 1938 tournament?’

11893. James Mason/Patrick Dwyer

Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) asks whether, further to C.N. 6126 and our feature article on R.J. Buckley, any new information is available from a reliable source as to whether James Mason’s original name was Patrick Dwyer.

11894. Frank Marshall

On the subject of Chess and Tobacco, Miquel Artigas (Sabadell, Spain) reports that he owns this postcard:

11895. 1 b4

Further to our recent feature article on the opening moves 1 b4 and 1...b5, Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) provides three further nineteenth-century specimens which began with 1 b4:

P.J. Doyle – Albert Cohnfeld

New York, 30 September 1877

1 b4 e5 2 Bb2 d6 3 c4 Be7 4 Nc3 f5 5 e3 Nf6 6 d4 exd4 7 exd4 O-O 8 Nf3 Ne4 9 Be2 Nd7 10 O-O Ndf6 11 h3 Qe8 12 a3 Nxc3 13 Bxc3 Ne4 14 Qc2 Qg6 15 Bd3 Bf6 16 Bb2 Re8 17 Rae1 Bd7 18 Re3 Re7 19 Bc1 Rae8 20 d5 f4 21 Bxe4 Rxe4 22 Rxe4 Rxe4 23 Nd2 Bf5 24 Qb3 Rd4 25 Kh2 Rd3 26 Qa2 Qh5 27 f3 Qh4 28 Ne4 Bxe4 29 fxe4 Qg3+ 30 Kg1 Be5 31 Qe2 f3 32 Rxf3 Rxf3 33 Qxf3 Qe1+ 34 White resigns.

Source: Dubuque Chess Journal, December 1877, page 322.

William M. De Visser – Peters

New York, circa 1879

1 b4 e5 2 Bb2 d6 3 c4 Nf6 4 e3 Be7 5 Be2 Bd7 6 a3 b6 7 Nf3 Bc6 8 d4 exd4 9 exd4 O-O 10 d5 Bd7 11 Bd3 Ne8 12 Qc2 h6 13 O-O c5 14 Nc3 Bg4 15 Kh1 Nd7 16 h3 Bh5 17 Ne4 Bg6 18 Rae1 Kh8 19 Nh2 Ndf6 20 f4 Nxe4 21 Bxe4 Bxe4 22 Qxe4 Bf6 23 Bc1 Bc3 24 Rd1 f5 25 Qf3 cxb4 26 axb4 Bxb4 27 g4 Bc5 28 g5 Kh7 29 Bb2 Qd7 30 Rde1 Qf7 31 Re6 hxg5 32 fxg5 g6 33 Qh5+ gxh5 34 Rh6+ Kg8 35 Rh8 mate.

Source: Newark Sunday Call, 2 March 1879.

Preston Ware – Henry William Birkmyre Gifford

Paris, circa 1882

1 b4 e5 2 Bb2 f6 3 a3 d5 4 e3 Bd6 5 c4 dxc4 6 Bxc4 Ne7 7 Ne2 Bf5 8 d4 exd4 9 Nxd4 Qd7 10 O-O Nbc6 11 Nc3 Nxd4 12 Qxd4 Be6 13 Rfd1 Rd8 14 Bxe6 Qxe6 15 Qxa7 O-O 16 Qxb7 Qb3 17 Rab1 Be5 18 Rdc1 Rd3 19 Ba1 Qxa3 20 Nb5 Qa2 21 Nd4 Rd2 22 Qf3 Ng6 23 g3 Bd6 24 Nb3 Ne5 25 Qg2 Re2 26 Nd4 Rd2 27 Bc3 Nd3 28 Ra1 Rxf2 29 Rxa2 Rxg2+ 30 Kxg2 Nxc1 31 Rd2 Ra8 32 Nb5 Na2 33 Nxd6 Nxc3 34 Rc2 Ra2 35 Rxa2 Nxa2 Drawn.

Source: Chess Player’s Chronicle, 24 May 1882, page 247.

11896. Midshipman John Cochrane

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘A rare glimpse of John Cochrane as a midshipman is to be found in a personal memoir written by John Harvey Boteler (1796-1885). It suggests that Cochrane was already a conspicuously strong player when he served in the Royal Navy. The account, entitled Recollections of My Sea Life from 1808-1830, was printed for private circulation in 1883. Boteler was appointed to HMS Antelope as a Lieutenant on 3 October 1815. His description of the ship’s activities in the Leeward Islands, in the West Indies, contains the following passage on pages 75-76:

“We had a midshipman, John Cochrane, a very admirable chess player. The admiral, who was fond of the game and not by any means a bad hand at it, used to send for Cochrane, who would generally beat him two out of three. We always knew how the game went by the temper of the admiral, and once or twice we asked Cochrane to give him a game to put him in a good humour; this was no go. Cochrane would be outside the mids.’ mess-place and play two games with anyone without seeing the board, and it was marvellous how rapidly his skill got wind among the islands. Directly we anchored some challenge would come off for a trial of strength.”

Cochrane’s sparring partner was Rear-Admiral John Harvey (1772-1837), Boteler’s uncle.

John Cochrane’s service on HMS Antelope had ended by 13 May 1819, when, as was established in C.N. 11102, he was admitted to the Inner Temple.

Some obituaries state that he served as a midshipman on board the Bellerophon. However, they blot their copy-books if they go on to say that the Bellerophon conveyed Napoleon to St Helena, since it only took him to England. This lowers somewhat the credibility of the Bellerophon story, but the first part could still be true and he could have joined HMS Antelope after leaving the Bellerophon. A search in Bellerophon’s log (National Archives, ADM 53/192) in the period immediately before and after Napoleon’s capture, resulted in the following entry being noted, dated 13 July 1815:

“Received on Board Napoleon Buonaparte late Emperor of France.”

No mention of Cochrane was found, but, for a definitive answer to this Bellerophon uncertainty, the ship’s muster and pay records should be searched.

The Royal Navy had at least one other very strong player about this time in Lieutenant Harry Wilson. C.N.s 6506 and 6532, contributed by Rod Edwards, refer to Wilson’s having once given odds of a knight to Labourdonnais.’

11897.

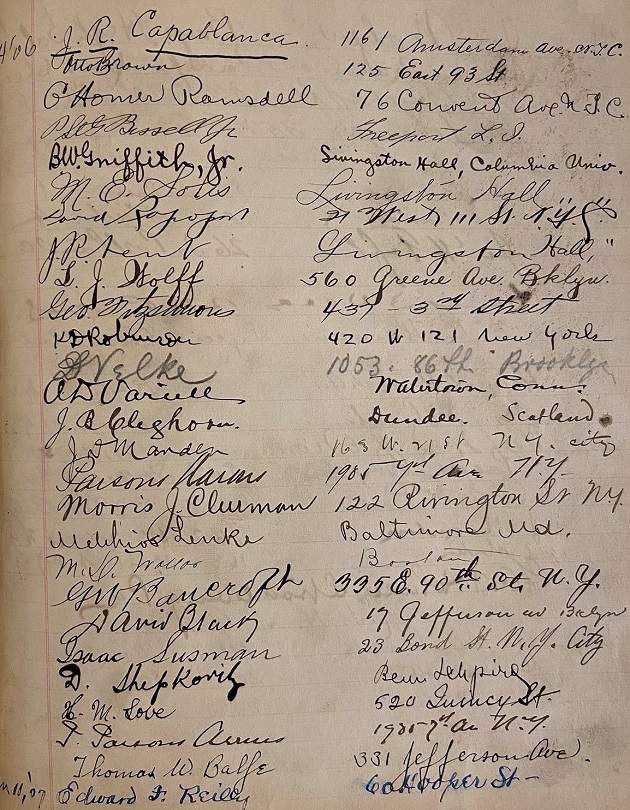

Brooklyn Chess Club

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) sends a page from the Brooklyn Chess Club’s Visitors’ Book (1886-1928), the original of which is held by the Center for Brooklyn History. The entries relate to 24 November 1906, and, as regards the first of them, 1161 Amsterdam Avenue may be noted as a residence close to Columbia University.

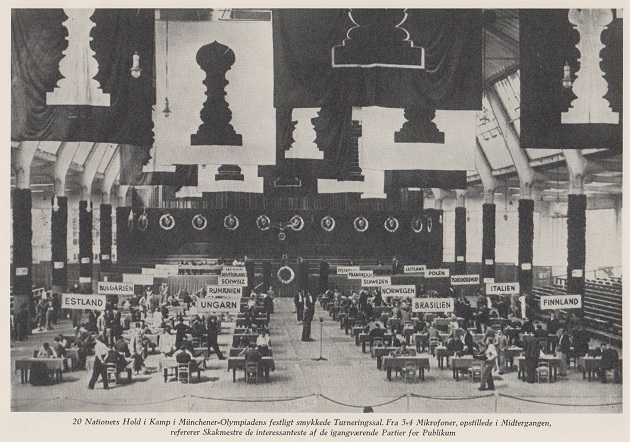

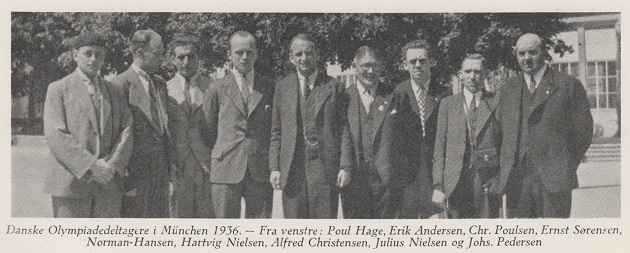

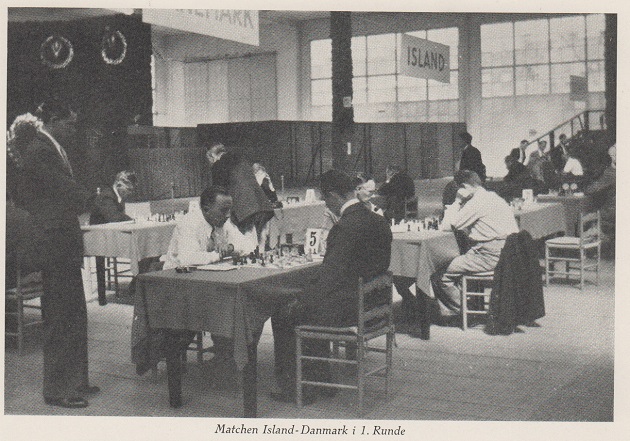

11898. Munich, 1936 Olympiad

Four photographs are being added to our feature article on the 1936 Munich Olympiad from, respectively, pages 127, 202, 203 and 207 of Alt om Skak by B. Nielsen (Odense, 1943):

11899. James Mason/Patrick Dwyer (C.N. 11893)

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘In answer to your correspondent’s query in C.N. 11893, it seems fair to say that there is a lack of direct evidence linking Patrick Dwyer to James Mason, and, hence, the case for it is not a strong one.

In addition, a specific (and almost certainly fatal) flaw in the argument may be found in the circumstances of the baptism of “Pat Dwyer”, which was discussed in an article by Jim Hayes, entitled “James Mason 1849-1905”, on the Irish Chess Union website. Mr Hayes commented:

“... the balance of probability being that Patrick Dwyer, son of John Dwyer with mother’s maiden name given as Mary Dwyer, both of Barrack Street, Kilkenny, who was baptized on 20 November 1849, in St John’s parish in the city of Kilkenny, was to become the future James Mason.”

This baptism register can be viewed on-line at Ancestry.com. Two pages further on in the same register (on page 114) is to be found the baptism of a second “Pat Dwyer”, evidently to the same parents, on 9 March 1850. The normal reason for parents reusing a forename is that the first child has died, and there seems no reason to suspect that this is an exception (although it would obviously mean that the first baby of that name had been born at least nine months before 9 March 1850).

That the parents were the same in the two baptismal entries is corroborated by the names of the godparents and the place of residence, both of which are identical. The only slight irregularity, which is of no consequence, is that the parents in the first baptism were recorded as John Dwyer and “Mary D[itt]o”, while in the second entry the mother’s former surname is given, Mary Walsh, as is common practice in Catholic registers, and in keeping with other entries in this one.

As regards the “Pat Dwyer” who was baptized on 9 March 1850, there seems little reason for anyone to suggest that he could have become James Mason. To judge from remarks made by Mr Hayes in his article, it would seem that baptism within a day or two of 19 November 1849 was a key factor in his choice of Patrick Dwyer.’

11900. Nona Gaprindashvili

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) provides three portraits from the Sputnik archive, reproduced here with permission:

October 1962

July 1967

December 1972

11901. Was Bogoljubow a hypermodern player? (C.N.s 653, 8003 & 10031)

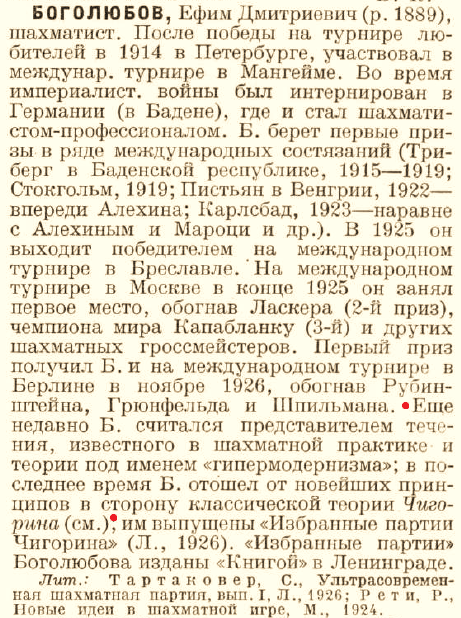

As shown in Hypermodern Chess, a few C.N. items have discussed whether or not Efim Bogoljubow was a hypermodern player. Now, Dmitriy Komendenko (St Petersburg, Russia) submits the entry on the master in volume six of the first edition (1927) of the reference work Большая советская энциклопедия:

The highlighted passage asserts that until recently Bogoljubow had been regarded as a representative of hypermoderism but that, of late, he had moved away therefrom to the classical theory of Chigorin:

‘Ещё недавно Б. считался представителем течения, известного в шахматной практике и теории под именем “гипермодернизма”; в последнее время Б. отошёл от новейших принципов в сторону классической теории Чигорина.’

11902. Bogoljubow on Alekhine

Our correspondent Dmitriy Komendenko also asks whether documentation exists on Bogoljubow’s reaction to Alekhine’s death in 1946 and to the procedure for establishing the world champion’s successor. On the latter point, attention is drawn to a brief note (C.N. 2704) in Interregnum.

11903. Goniff/Ganef/Gonim/Ganeff (C.N. 6513)

Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) refers to two articles on his Jewish Chess History website, A Porat Interview, a Najdorf Quip, and a Nimzowitsch Story and ‘Ganef:’ The other Side of the Story. He also comments to us:

‘“Ganef” is customarily used as a mild expression of annoyance or disapproval, often humorously, and not as a literal claim that someone is a thief or scoundrel.’

11904. José Antonio Gelabert (C.N.s 4232 & 11609)

Yandy Rojas Barrios (Cárdenas, Cuba) sends this further portrait of Gelabert, from page 101 of Capablanca-Magazine, 31 May 1913: