Chess

Notes

|

| First column | << previous | Archives [71] | next >> | Current column |

6596. Chess Masters in Action (C.N. 6587)

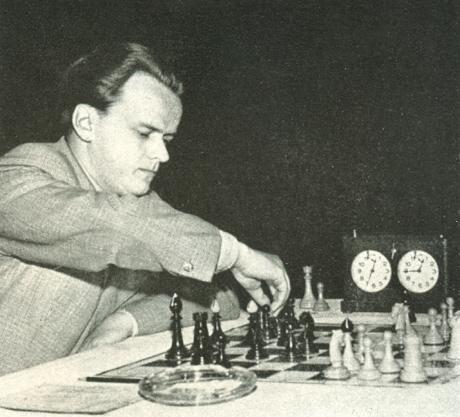

C.H.O’D. Alexander

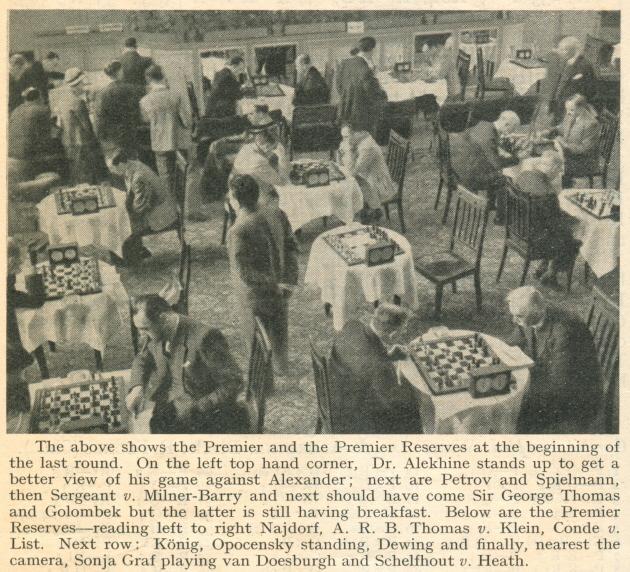

We have acquired the full article ‘Chess Masters in Action’ by C.H.O’D. Alexander, which was published on pages 79-82 of the Irish Digest, October 1959. Extracts are provided below, and there is a surprise concerning the monk/scientist quote attributed to Alekhine (C.N. 6587).

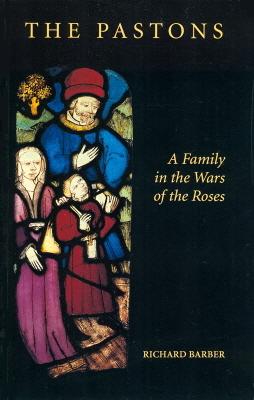

‘Dr Emanuel Lasker, world champion for 27 years from 1894, I met in 1936 when he was well on in the 60s and far past his best, though still good enough to dispose of me. A rather small man with strong aggressive features, he produced even at that age a tremendous impression of toughness and of an endlessly resourceful fighting spirit; I have always thought him the greatest tournament player of all time.

He was unrivalled in his ability to win lost games – he never gave up hope and he had a genius for making his opponents play the kind of positions that did not suit them. He would get the steady players into positions where adventurous play was needed and the brilliant players into positions where consolidation was required; you were never allowed to be comfortable against Lasker.’

‘Capablanca ... had an Olympian attitude to the game and his opponents; he knew he was better than you and since he proposed to play the correct moves (all of which were pretty obvious, anyway) he did not anticipate much difficulty in demonstrating it. If things had been a little harder for him he might in the end have been an even greater player, and better able to resist the impact of a player of equal genius and a greater passion for the game – Alexander Alekhine.’

‘Capablanca knew he was much better than anyone else and took it for granted; Alekhine never quite believed it and was always out to demonstrate it yet again to reassure himself. An intensely nervous, dynamic character, the way he moved his pieces was almost like a physical attack. Capablanca gave you the impression that disposing of you was a piece of routine, to be got over as quickly as possible; Alekhine, you felt, intended to give you a lesson you would not quickly forget for your impertinence in daring to oppose him.

I remember a curious incident in one of my games with Alekhine. Someone told me that when Alekhine was worried about his position he always twisted his hair with his fingers. In 1938 I played Alekhine in the Margate tournament and he made what looked to me like a weak move in the opening; I made my reply with a nervous feeling that I had probably overlooked something. What was my delight to see Alekhine, after a minute or two’s reflection, start to twist his hair.

This was about 10.0 a.m., and from then till 2.30 (it was the last day of the tournament and no adjournment for lunch allowed) Alekhine sat without leaving the board, and through all the turns of a complex game continued (to my great moral support) to twist his hair.

At 2.30 I made a slight tactical error and let my advantage slip; Alekhine moved, took a comb out of his pocket, ran it through his hair, got up, and walked up and down the tournament room. My own judgment (that my advantage was gone) was thus confirmed as clearly as if he had told me so, and I took an immediate opportunity to force a draw before worse befell me.’ [Alexander’s notes to the game are on pages 75-77 of the Golombek/Hartston monograph on him, having originally appeared on pages 282-283 of the June 1938 BCM. The photograph below was published on page 266 of the same issue of the BCM.]

‘For me, Alekhine will always epitomize chess, and I shall always remember my games with him with pleasure, even though he did win a brilliancy prize against me for one of them.’

‘[Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine] all had a genius for the game. Euwe, though he had great natural talent, always struck me as essentially a man of high all-round ability who systematically devoted this ability to making himself a great chessplayer.

Everything that could be learnt about chess Euwe learnt, and taught to others ...’

‘Smyslov, a big slow-spoken redhead in the middle 30s who looks more like a Scot than a Slav, has a style as massive as his personality; after being beaten by Smyslov you feel as if you have been run over by a steamroller.’

‘Botvinnik is in the greatest tradition of world champions, with Morphy, Lasker, Capablanca and Alekhine. Playing him, one gets a strong sense of someone dedicated to the game – a mixture of monk and scientist. When I played Botvinnik in Amsterdam in 1954 I was temporarily demoralized by watching him write down his first move. Slightly short-sighted, he gave his entire attention to recording the move in the most beautifully clear and precise script; only after completing this to his entire satisfaction did he again bend his mind to the game. This calm but intense concentration on even the most trivial aspect of the game made me feel like a fly under the scientists’ microscope.’

From that final extract it can be seen that (contrary to the impression derived from the Google Books snippet) the description ‘a mixture of monk and scientist’ concerned Botvinnik, not Alekhine. Nonetheless, as noted in C.N. 6587 the Mullen/Moss book Blunders and Brilliancies claimed that Alekhine had referred to ‘a research scientist, an ascetic monk and a beast of prey’.

C.N. 6587 also mentioned the possible relevance to C.N.s 4292 and 6185 of Alexander’s remark about how Botvinnik wrote down his first move.

The Irish Digest stated on page 79 that the article by Alexander was ‘condensed from The Listener’.

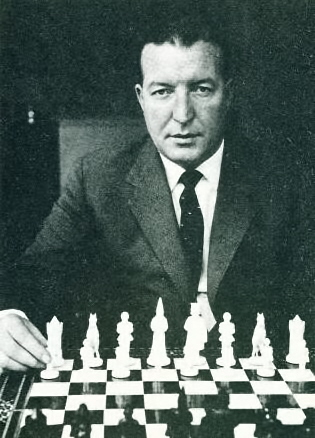

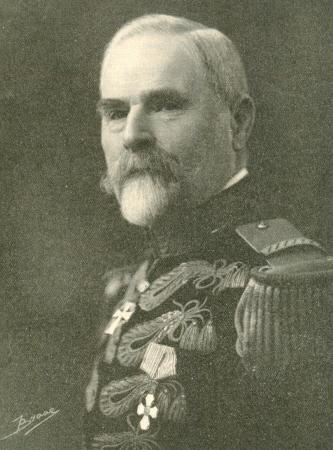

6597. Charles Haughey

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) submits this photograph of the late Taoiseach Charles Haughey:

Source: Page 227 of Ireland A History by Robert Kee (London, 1995).

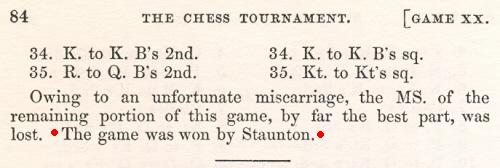

6598. Staunton v Horwitz, London, 1851

Mario Ziegler (Nonnweiler, Germany) refers to the fifth game in the Staunton v Horwitz encounter at the London, 1851 tournament. Page 84 of Staunton’s tournament book gave the moves 35 Rc2 Ng8 and then stated:

‘Owing to an unfortunate miscarriage, the MS of the remaining portion of this game, by far the best part, was lost. The game was won by Staunton.’

Our correspondent asks, firstly, whether the missing moves are available anywhere.

Secondly, he points out that if Staunton did indeed win that game his total score in the match against Horwitz would be +5 –2 =0, since all seven games (pages 71-88) were indicated as having a decisive outcome. However, page 38 stated:

‘In this section the victory in each contest was adjudged to the player who first won four games.’

Moreover, page 174 gave the final score between Staunton and Horwitz as +4 –2 =1. The question, therefore, is which of the seven games was drawn.

We note that page 219 of the 1851 Chess Player’s Chronicle stated that it was the fourth match-game, but can that be so? The tournament book (page 82) shows that game as finishing with an overwhelming advantage for Staunton (after his final move 33...b2):

Restrictions were initially placed on the dissemination of games from London, 1851, as shown by the first quotation in Copyright on Chess Games.

6599. Reshevsky v Myagmarsuren

In this position (Reshevsky v Myagmarsuren, Sousse, 1967) White played 28 Rbc1. David Abrams (Syracuse, NY, USA) writes that although that move was the subject of no remarks on page 132 of Winning Chess Strategies by Y. Seirawan with J. Silman (Redmond, 1994 and London, 2003), 28 Nxd5 is much stronger.

We add that the game was annotated on pages 14-15 of Chess Review, January 1968 by Hans Kmoch, who commented as follows on Black’s previous move (27...Rec8):

‘Black is speculating on 28 Nxd5? a6!’

However, Yasser Seirawan (Amsterdam) informs us:

‘I too was seduced by the idea that the retort 28...a6 would refute the capture of the pawn at d5. That is not the case, as the continuation 29 Rxc6 axb5 30 Rxc8+ Kg7 31 Nxb6 (the move I had missed) and 32 Rxb5 is a clean win for White.’

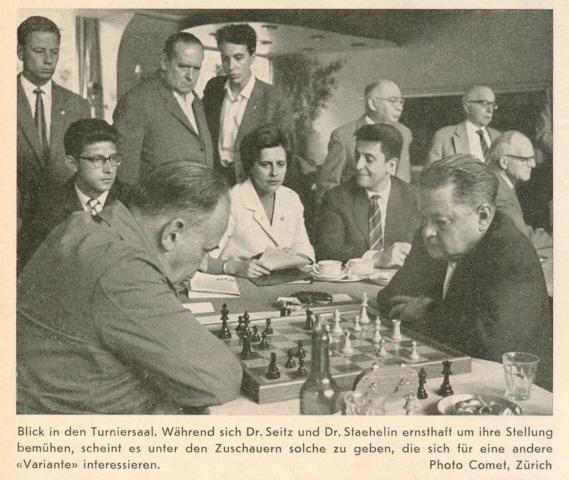

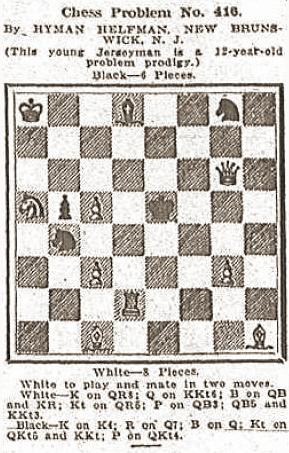

6600. First tournament for seniors

Which was the first tournament exclusively for senior players? A possibility mentioned on page 390 of Schachgesellschaft Zürich 1809 bis 2009 by R. Forster (Zurich, 2009) is the Frascati Seniors’ Tournament in Zurich, June-July 1962. It was won by H. Grob and B. Kostić ahead of H. Müller, O. Zimmermann, J.A. Seitz, H. Johner, A. Staehelin, A. Brinckmann, W. Henneberger and E. Szabados.

This photograph from a contemporary issue of the Schweizer

Illustrierte

Zeitung is given in the book:

Left to right: H. Grob, W. Henneberger, O. Zimmermann, H. Johner and A. Staehelin

The following shot was published on page 184 of the September 1962 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

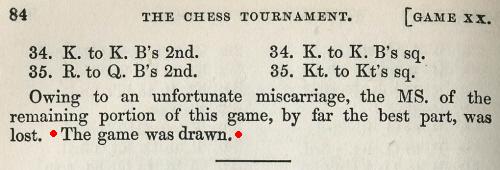

6601. Staunton v Horwitz, London, 1851 (C.N. 6598)

C.N. 6598 quoted the concluding note on page 84 of Staunton’s book on the London, 1851 tournament, concerning his fifth match-game against Horwitz:

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) points out that in a subsequent edition of the tournament book (published by Bell & Daldy, London in 1873) the text was amended to state that the result was a draw:

Below is the title page of the 1873 edition:

6602. Steinitz on Gossip

From page 143 of the May 1891 International Chess Magazine:

6603. Boys’ Life

Regarding Fischer’s chess column in Boys’ Life, Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) informs us that virtually the complete run can now be consulted via Google Books. Our correspondent has assembled the relevant links on a webpage of the Fédération Echiquéenne Francophone de Belgique.

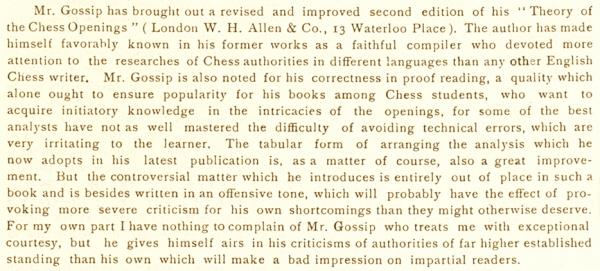

Monaco, 1967 (Chess Life, June 1967, page 146)

6604. Turgenev v Kolisch (C.N.s 5863 & 6054)

Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy) quotes from page 9 of La Nouvelle Régence, January 1862:

‘M. Tourguéneff vient d’engager avec M. Kolisch un match au demi-cavalier. Cette lutte produira probablement quelques nouveaux chefs-d’œuvre que notre rédacteur en chef s’empressera de publier.’

The game discussed in C.N.s 5863 and 6054 appeared on page 269 of the June 1862 issue, the conclusion being 21 Qxc3 Qe2 mate.

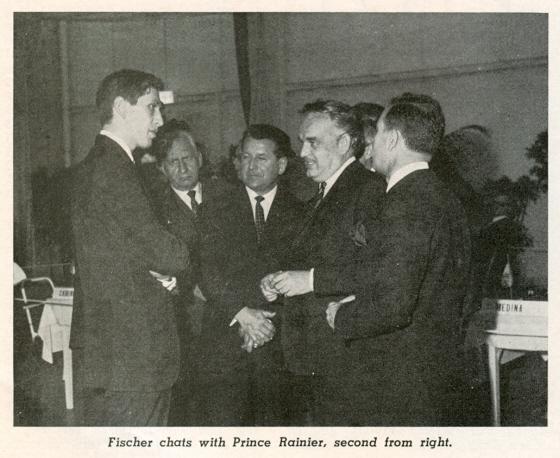

6605. Georg Marco’s brother (C.N.s 6227, 6231 & 6235)

A problem by Michael Marco, aged 11, was published on page 1287 of the Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung of 27 November 1887 and has been forwarded to us by Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

6606. D. Leslie v A. Bisguier

Bisguier’s first-round game in the Southsea tournament, 12 April 1950 is given in databases as follows:

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 d5 3 Nbd2 Bf5 4 c4 c6 5 g3 Nbd7 6 Bg2 e6 7 O-O Bd6 8 cxd5 cxd5 9 Nh4 Bg4 10 f4 Rc8 11 Qe1 Qb6 12 Nb3 Rc2 13 Bd2 O-O 14 h3 Bf5 15 Nxf5 exf5 16 Bc3 Re8 17 Bf3 Ne4 18 Qd1 Rxc3 19 bxc3 Nxg3 20 Qd2 Nxf1 21 Rxf1 Nf6 22 e3 Ne4 23 Qd3 Bf8 24 Bxe4 fxe4 25 Qe2 Rc8 26 Rc1 Rc6 27 c4 Qa6 ‘0-1’.

However, John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) draws attention to the additional moves in the New York Times, 16 April 1950, page S4: 28 Kf2 dxc4 29 Nd2 f5 30 Rxc4 Qxa2 31 Rxc6 bxc6 32 Qc4+ Qxc4 33 Nxc4 c5 34 d5 Kf7 35 Ke2 Ke7 36 Kd2 h6 37 Kc3 g5 38 fxg5 Bg7+ 39 Kb3 hxg5 40 Na5 g4 41 hxg4 fxg4 42 Kc4 g3 43 Kxc5 g2 44 Kc6 g1(Q) 45 d6+ Ke6 46 Nb7 Qxe3 47 Nc5+ Qxc5+ 48 White resigns.

We note that on page 6 of the tournament book the game ended ‘27 P-B4 Q-R3 and Black won’.

Bisguier finished equal first with Tartakower, ahead of Golombek, Penrose and Schmid, with Bogoljubow in sixth place. From page 153 of the May 1950 CHESS:

‘... Sixteen-year old Jonathan Penrose beat in turn Prins, Bogoljubow and Tartakower, and 72-year-old problem expert, F.F.L. Alexander, created almost as great a stir by defeating Bogoljubow and Golombek. The publicity might have blazed far higher had not young Jonathan, approached by eager Press men, flatly refused to be “interviewed” or quoted in any way.’

Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia records that Frederick Forrest Lawrie Alexander was born on 13 November 1879, which means that he was 70 at the time of the Southsea tournament. On page 144 of the May 1950 BCM Golombek wrote:

‘At the beginning of the Congress strangers were wont to ask if he was any relation of C.H.O’D. Alexander; towards the end people were inquiring if C.H.O’D. Alexander was any relation of his.’

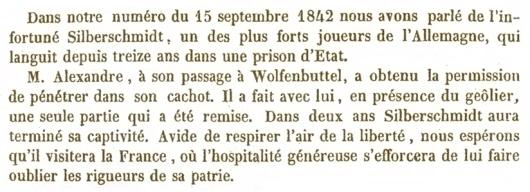

6607. Alekhine v L. Zollner

As noted on page 629 of the Skinner/Verhoeven volume on Alekhine’s games, Louis Zollner was aged 84 when he defeated the world champion in a simultaneous display in Newcastle on 24 September 1938. The game, in which Alekhine played the Evans Gambit, was taken from page 102 of CHESS, 14 November 1938, where it was part of a seven-page feature on Zollner. Regarding his victory, in 30 moves, Zollner commented: ‘This must be my farewell effort, I fear.’

Louis Zollner (1854-1945). Source: CHESS, 14 November 1938, page 99.

6608. New York, 1924

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) raises two matters concerning New York, 1924 on the basis of information in the tournament book: a) the speed with which the event was organized and b) the pairing system used.

We offer some supplementary facts from the 1924 volume of the American Chess Bulletin, whose editor, Hermann Helms, was on the board of the tournament directors.

Page 1 of the January 1924 issue announced the proposed tournament:

‘First steps were taken at a meeting in New York on 18 January, having in view a possible gathering of the world’s leading experts as early as 17 March.

As we go to press, there is no absolute certainty as to its taking place, as planned. It is sufficient to say that a number of good men and true are bending all their energies to make it so. Should success crown their efforts, then the congress will be quite unique in the annals of the game, at least in so far as rapidity of action is concerned.

This much can be said. Thanks to good use of the cable, the readiness of several European masters to come over has been ascertained.’

And from page 2:

‘Although a total of nearly $10,000 will be required to defray the expenses, including the prizes, as well as the transportation of several European experts, close upon $4,000 was pledged as a starter [at the committee’s meeting on 18 January].

The members of the committee undertook to raise most of the balance through subscriptions within a fortnight, after which word was to be sent to Europe to the masters who are in readiness to come whenever the call is issued.’

Page 25 of the February 1924 Bulletin stated:

‘Since the announcement made in the January issue of the Bulletin, matters have progressed famously in connection with the New York International Chess Masters’ Tournament. It is now an assured fact. New York, therefore, will be the scene for a gathering of the world’s most famous masters, the like of which is not apt to be witnessed again in our generation.’

Page 4 of the tournament book reported:

‘With the hearty co-operation of Dr Arthur A. Bryant [the Treasurer] and Mr Helms, the preparations at this end were carried forward with the least possible delay, and on 8 March we were able to welcome the masters at the docks with the satisfying knowledge that everything was ship-shape, barring, perhaps, some of the masters. Several unforeseen incidents helped to maintain the interest and contribute a bit of anxiety, chiefly the illness of Capablanca from a severe attack of la grippe, which made his participation in the tournament somewhat doubtful up to the last minute.’

Source: page x of the tournament book.

The pairing system was set out in point 19 of the tournament rules (pages 27-28 of the February 1924 American Chess Bulletin):

‘The draw will be made according to the Berger system and the players will draw their own numbers before beginning of the tournament. The number of the round to be played each day will be decided by draw and announced 15 minutes before beginning of playing hours. The first half of the tournament must be completed before any of the rounds of the second half are drawn.

The draw for numbers took place on 11 March (American Chess Bulletin, March 1924, page 49), and the first round of play was on 16 March.

Mr Niessen asks whether other major tournaments have handled pairing in a similar way.

6609. Pomar v Bernstein (C.N.s 6573 & 6584)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) reports that the third Pomar v Bernstein photograph in C.N. 6573 was published on page 42 of ABC, 20 January 1946. There was a picture credit to ‘Ortiz’.

He also draws attention to page 2 of El Mundo Deportivo, 24 January 1946, which mentioned that a photograph of Pomar in play against Bernstein had been published in the New York Times.

We have found that picture (the second one in C.N. 6573) on page 35 of the sports section of the New York Times, 22 January 1946. The (faulty) caption was: ‘Arturito Pomar of Madrid during his match with Dr O.S. Bernstein of Paris at international event in London. The young Spaniard and his opponent played to a draw.’

6610. Hirsch Hermann Silberschmidt (1801-66)

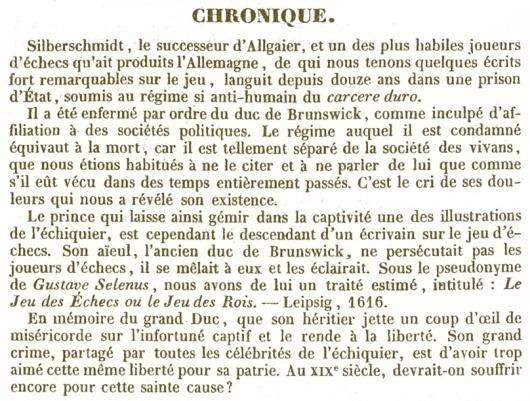

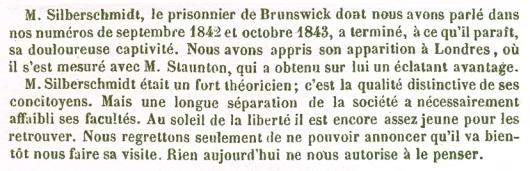

Concerning Silberschmidt’s imprisonment, three items are reproduced:

Le Palamède, 15 September 1842, page 138

Le Palamède, 15 October 1843, page 473

Le Palamède, 15 June 1844, page 280

The third item refers to Silberschmidt’s play against Staunton. Two game-scores, both wins for the Englishman (‘they possess no remarkable merit’), are on pages 182-183 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1844.

6611. Both colours

Alexander Jablanczy (Sault Ste.

Marie, Ontario, Canada) notes in a ChessBase article

on the 2010

Czech Championship that some of the pieces have

heads of the opposite colour. Is information available

about the origins and extent of this style, which

particularly concerns the bishops and has been prevalent

chiefly in Eastern Europe? See, too, for instance,

illustrated reports on tournaments in Hungary.

Below is a photograph of L. Pachman from Nad šachovnicemi celého světa by K. Opočenský and V. Houška (Prague, 1960):

A variant is shown by this picture of Karel Hromádka on page 114 of the Podĕbrady, 1936 tournament book:

6612. Identifying Black

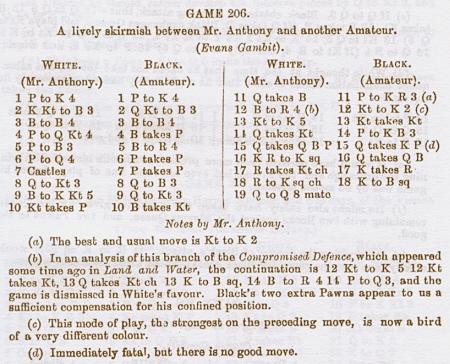

A nineteenth-century miniature:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Ba5 6 d4 exd4 7 O-O dxc3 8 Qb3 Qf6 9 Bg5 Qg6 10 Nxc3 Bxc3 11 Qxc3 h6 12 Bh4 Nge7 13 Ne5 Nxe5 14 Qxe5 f6 15 Qxc7 Qxe4

16 Rfe1 Qxh4 17 Rxe7+ Kxe7 18 Re1+ Kf8 19 Qd8 mate.

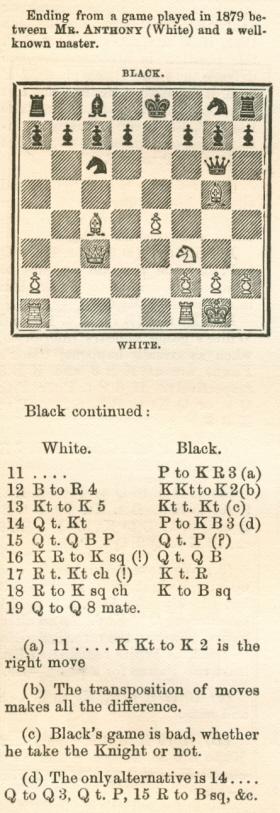

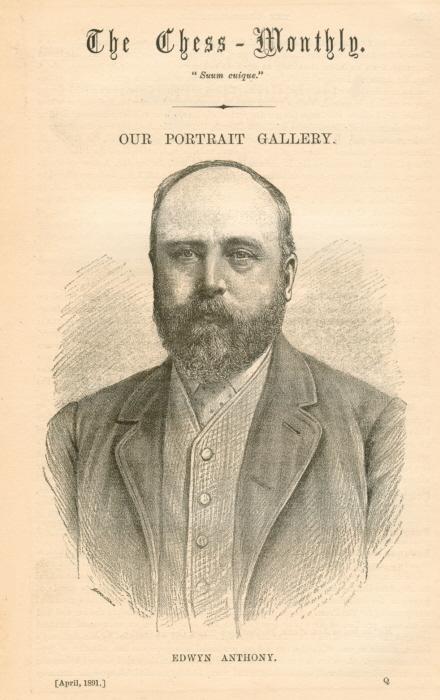

It was published on page 9 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1 January 1879 as a win by Anthony against ‘another Amateur’:

When, however, the latter part of the game was given on page 250 of the Chess Monthly, April 1891, Black was referred to as ‘a well-known master’:

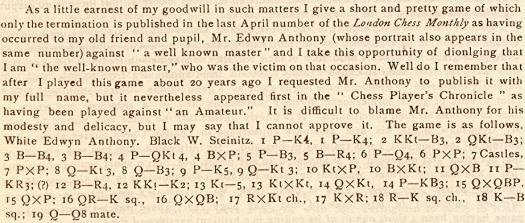

In fact, Black was Steinitz, as the world champion himself disclosed on page 236 of the August 1891 issue of the International Chess Magazine:

It will be noted that in addition to the faulty game-score from Steinitz there is a discrepancy over 1879 and ‘about 20 years ago’.

6613. An interview with Alekhine

Page 1 of the Tribune de Genève, 27-28 September 1925:

Much of the interview with Alekhine, which was conducted by Albert Haubrechts, was quoted on page 14 of the excellently-researched Aljechins Besuche in der Schweiz 1921-1934 by Toni Preziuso (Suhr, 1991).

6614. Lasker v M. Chernev

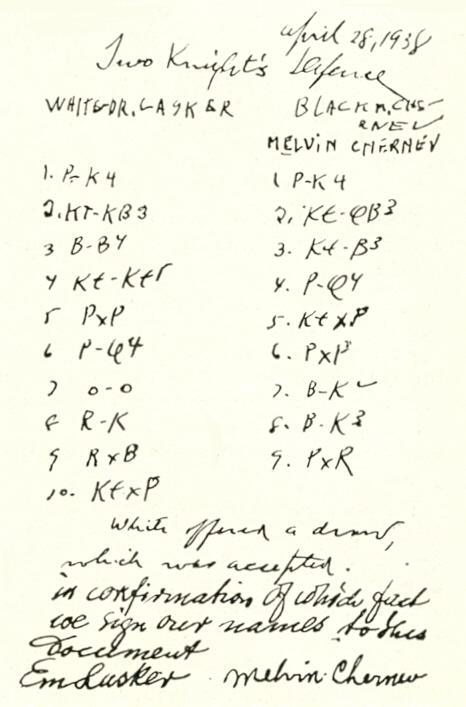

On page 14 of the October 1974 CHESS Irving Chernev reported that on 28 April 1938 his son Melvin, then aged eight, played a game against Emanuel Lasker when the latter visited the Chernevs’ home. Chernev senior recounted:

‘After ten moves, Lasker said, “Would you accept a draw?” Mel turned to me and said, “Should I take a draw, Dad?” I advised him to do so, whereupon they shook hands on it.

I wrote on the score-sheet, “White offered a draw, which was accepted.”

Lasker added this: “In confirmation of which fact we sign our names to this document.”

Both contestants gravely signed their names to the score-sheet.’

The document was then reproduced in CHESS:

6615.

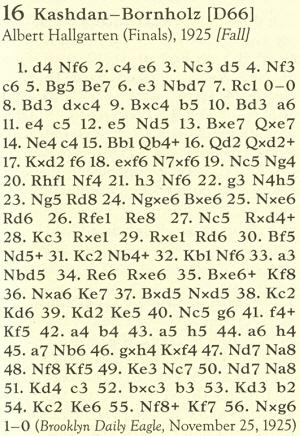

Capablanca v Kashdan or Kashdan v Capablanca?

A game played in the New York, 1931 tournament:

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 c6 3 d4 d5 4 Nc3 e6 5 Bg5 Nbd7 6 e3 Be7 7 Qc2 O-O 8 a3 Re8 9 Bd3 dxc4 10 Bxc4 Nd5 11 Bxe7 Qxe7 12 Ne4 Rd8 13 O-O Nf8 14 Rfe1 b6 15 Rac1 Bb7 16 Qe2 a5 17 Ne5 f6 18 Nf3 Kh8 19 Nc3 Nxc3 20 Rxc3 e5 21 Rd1 exd4 22 Rxd4 Rxd4 23 exd4 Qxe2 24 Bxe2 Re8 Drawn.

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) notes that this game was played between Capablanca and Kashdan but asks who was White. He points out that whereas databases indicate Capablanca, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of 4 June 1931 (page 26) had Kashdan as White.

We offer a number of comments:

- The game was played in the final round, on 3 May 1931, when Capablanca was already assured of first prize. In the preceding ten rounds both Capablanca and Kashdan had an even distribution of games as White and Black.

- The game was published on page 26 of the sports section of the New York Times, 4 May 1931 with Kashdan as White. The newspaper reported:

- On page 95 of the May-June 1931 American Chess Bulletin too, Kashdan was identified as White in the heading to the game-score.

- We have two New York, 1931 tournament books, by J. Spence (Omaha, 1953) and by L. Eceizabarrena Gaba and R. Alvarez Cela (Madrid, 1976). Both stated that Kashdan was White against Capablanca. (Both also gave the clock-times as 58 minutes for White and 70 minutes for Black.)

- Page 125 of Isaac Kashdan, American Chess Grandmaster by Peter P. Lahde (Jefferson, 2009) specified ‘New York, 1931’ as the source for the game, yet put Capablanca as White.

- The Spanish tournament book (page 224) and the Lahde volume noted that the position after 13...Nf8 had occurred in round nine of the tournament (Kashdan v Kupchik), where Kashdan played 14 Rad1.

- The foregoing may be regarded as overwhelming evidence that Kashdan played White against Capablanca.

- The only cause for any slight doubt stems from the admirable volume on Capablanca’s tournament and match games compiled by J. Gilchrist and D. Hooper and published in 1963 in the ‘Weltgeschichte des Schachs’ series: it had Capablanca as White. Was that a rare mistake by two fine researchers? Or had ‘Capablanca v Kashdan’, as opposed to ‘Kashdan v Capablanca’, already appeared in a pre-1963 source?

‘It was the first tournament encounter between these two experts, neither of whom suffered a single defeat since the beginning of the competition on 18 April. The play was wholly positional and quite uneventful.

Both proceeded with the utmost care and gradually pieces were changed off until each was left with a rook, bishop and knight, in addition to six pawns.

After that there was little left to play for and when Capablanca proposed a draw Kashdan readily accepted.’

6616. Kasparov protiv Karpova

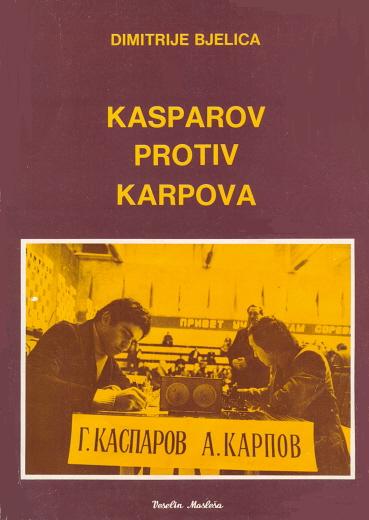

We have written elsewhere about Mr Dimitrije Bjelica and his copying, but his book Kasparov protiv Karpova (Sarajevo, 1984) has only just come to our attention.

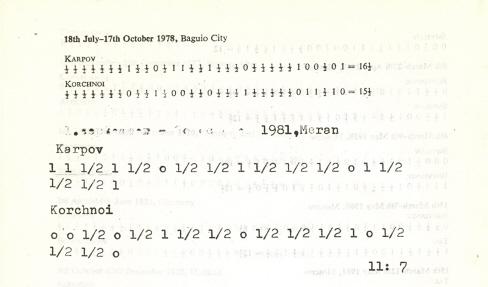

The multiplicity of formats, styles and typefaces pervading the book has an obvious explanation: Mr Bjelica’s clippers and glue-pot have been in action yet again. For example, pages 235-236 have a table of Karpov’s tournament results which is reproduced (without permission or acknowledgement, naturally) from a book edited by us, World Chess Champions (Oxford, 1981). Similarly, on pages 230-234 Mr Bjelica lifts (i.e. steals) from our book the entire list of 28 world championship matches held from 1886 to 1978. By the time Kasparov protiv Karpova was published, of course, Karpov and Korchnoi had played a further match, in Merano, and one can only marvel at the conscientious artistry with which Mr Bjelica updated our work:

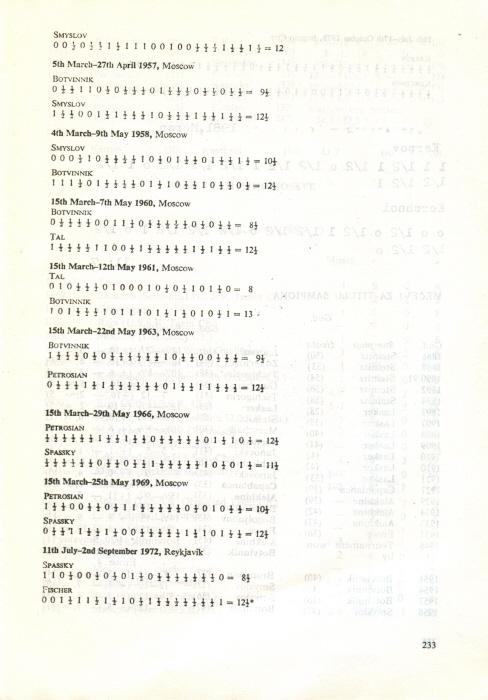

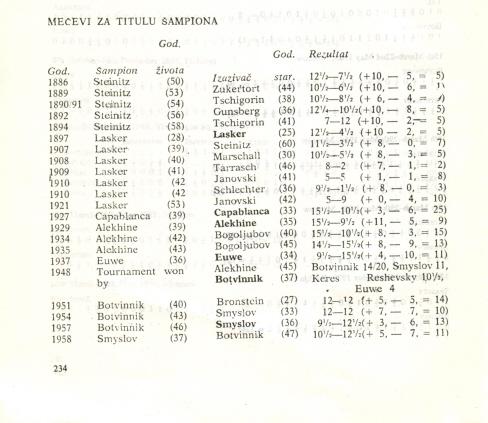

6617. World championship matches

Sandwiched between material plagiarized from World Chess Champions there appears on page 234 of Mr D. Bjelica’s Kasparov protiv Karpova a chart which, gratifyingly, does not come from our book:

6618. Goldstein on Przepiórka

Dawid Przepiórka (L’Echiquier, October 1927)

C.N. 687 provided, courtesy of John Roycroft (London), some extracts from a letter dated 14 October 1983 sent to him by Alexander/Aleksander Goldstein (1911-88), then of Australia and formerly of Poland.

Przepiórka ‘was a round, chubby man with a severe impairment of hearing ... All his life he was a person of ample independent means. ... In problems he used his qualities to promote the chess composition, in chess he rather promoted himself. Przepiórka’s name means partridge [sic – quail] in Polish ... He had a great liking for old and stale jokes and once he caught you, you had to listen. Marian Wróbel was the closest of his collaborators and as his name also means a bird in Polish (sparrow) one can imagine that this was another source of childish enjoyment for the Master, who claimed that a partridge is so much more important than a sparrow. And when someone observed that no-one is hunting sparrows, he laughed and considered it the most witty repartee. On the serious side he was an ardent fighter against the admission of Nazi Germany to FIDE ...’

Mr Goldstein left Poland in September 1939 and, upon his return in May 1946, ‘everything was in ruins. In the domain of chess composition I was probably the only survivor of Jewish origin. Przepiórka, J. Fux, S. Krelenbaum and Kozłowski (the endgame wizard) were all gone’. He mentioned that Wróbel published an article in 1955 (75 years after Przepiórka’s birth) in which he recalled that a makeshift chess club had been organized in a private dwelling and that the Germans made a raid some time in January 1940, arresting about ten players. After a week or so, the non-Jewish persons were released and Przepiórka, according to Wróbel’s statement, was executed in April 1940.

Mr Goldstein’s reminiscences concluded:

‘Now, when I come to think of it, I see how impractical the man was. He was so much exposed to the danger and most likely he had the means to escape. What a folly he committed by staying there, and how to explain it? Was he lured into false security by the image of the Germans he knew from his student days? But he knew and fought the Nazis. Or, probably he considered himself incapable of wandering around in crude conditions in foreign lands. The fact is that he perished, and we can console ourselves that after a period of 60 happy years he suffered only for six months. To conclude: Dawid Przepiórka as I knew him was a problemist only, and I have not enough praise for him as a creator of excellent problems, a man of culture and knowledge and a patron of young problemists of all sorts.’

6619. Capablanca v Kashdan or Kashdan v Capablanca? (C.N. 6615)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) notes the following:

1. Page 5 of the sports section of the New York Times of 3 May 1931 and page 2 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of the same date announced that the pairing for that day’s round 11 was Kashdan v Capablanca.

2. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle of 7 May 1931, page 32 published the full score of the game with Capablanca as White.

As mentioned in C.N. 6615, when the Brooklyn Daily Eagle gave the game on 4 June 1931 it stated that Kashdan was White.

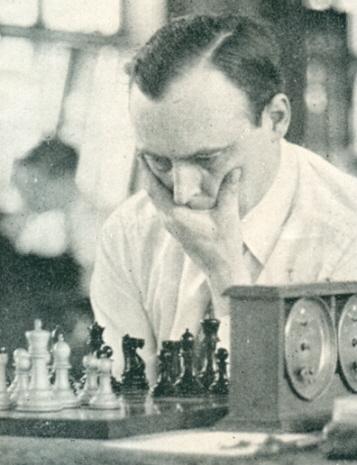

Isaac Kashdan

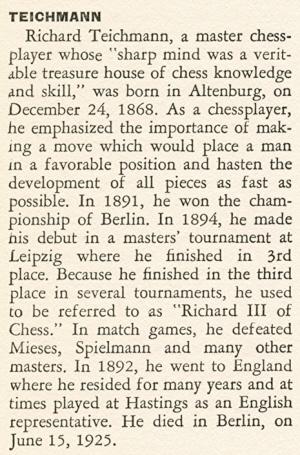

6620. Richard Teichmann

From Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA):

‘Richard Teichmann has often been referred to as a chessplayer who failed to achieve his potential. Alekhine’s remarks quoted on pages 394-395 of A Chess Omnibus provide an example, as do Jack Spence’s comments on page 4 of The Chess Career of Richard Teichmann 1892-1924 (Nottingham, 1971). Even in the Carlsbad, 1911 tournament book Vidmar states that Teichmann frequently finished fifth because he was comfortable in doing so, and only an “ungewöhnliche Stimulation” can have resulted in him playing as well as he did in that particular tournament (page 9).

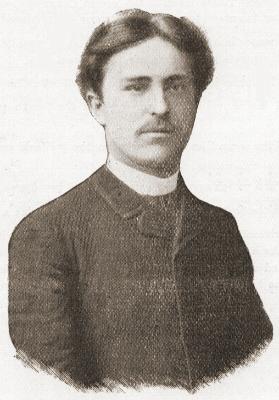

Richard Teichmann

One wonders how great a player Teichmann could have been. On pages 119-120 of E.A. Michell’s The Year-Book of Chess, 1907 (London, 1907) the introduction to Teichmann v Janowsky, Ostend, 1906 states:

“A famous player once said that Teichmann had as much chess in him as any man living. If anyone doubts this we recommend a careful study of the beautiful and subtle game below.”

Who was that “famous player”?’

Our correspondent also notes the entry on Teichmann in Byrne J. Horton’s Dictionary of Modern Chess (page 204):

We add that the ‘sharp mind’ remark appeared in an article ‘The Triumph of Unreason’ by H. Kmoch and F. Reinfeld on pages 299-300 of the October 1950 Chess Review (see too pages 158-165 of Reinfeld’s The Treasury of Chess Lore). The full paragraph on Teichmann reads:

‘Another member of the “older” generation was Richard Teichmann (born 1868), whose sharp mind was a veritable treasure house of chess knowledge and skill. The unfortunate Teichmann had two handicaps: he lacked the vision of one eye and he was undoubtedly the laziest man that ever lived. Many of his games are unbearably lethargic, but when the slumbering chess genius of Teichmann roused itself he was capable of superhuman achievements. This he proved when he won the great Carlsbad tournament in 1911.’

On page 123 of The Unknown Alekhine 1905-1914 (New York, 1949) Reinfeld wrote:

‘Richard Teichmann, a phenomenally gifted master, was greatly handicapped by laziness and the loss of an eye. He was generally found in the middle of the prize list, and won so many fifth prizes that he was nicknamed Richard the Fifth. Paradoxically enough, his only important first prize was at Carlsbad, 1911 – one of the great tournaments of chess history.

Curiously enough, Teichmann’s phenomenal laziness was blended with equally phenomenal patience. The following game [Alekhine v Teichmann, Carlsbad, 1911] is a case in point.’

C.N. 929 (see page 122 of Chess Explorations) briefly mentioned Teichmann’s nickname, and the above discrepancy between ‘Richard III’ (Horton) and ‘Richard V’ will be noted.

We do not recognize the quote by the ‘famous player’ referred to by Mr Beck. As regards other views on Teichmann, Emanuel Lasker wrote in a ‘Berlin Letter’ dated 30 October 1907 about an 11-round tournament in that city which Teichmann had just won:

‘His victory confirms the opinion held by connoisseurs that Teichmann can easily beat the young crop of masters in a short tournament and in fact is a redoubtable opponent for anyone. In a drawn-out contest, however, the loss of his right eye always proves too severe a handicap.’

Source: Lasker’s Chess Magazine, November 1907, page 4.

After Teichmann’s victory at Carlsbad, 1911 Lasker wrote about him in the Berliner Zeitung am Mittag. The article, ‘Der Sieg Teichmanns’, was reproduced on pages 299-300 of the September-October 1911 Wiener Schachzeitung.

Other authoritative assessments of Teichmann’s skill and potential will be welcome.

6621. Quiz question

On what date was this photograph taken?

6622. A fifteenth-century letter

From page 431 of A History of Chess by H.J.R. Murray (Oxford, 1913):

See also page 6 of Great Moments in Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1963), which referred to a letter written by Margery Paston to her husband, ‘apparently in 1484’.

Our modern-English edition of the Paston letters is The Pastons edited by Richard Barber (Woodbridge, 1993). Page 77 indicates that the letter was from Margaret Paston to her husband John, and that the date was 1459:

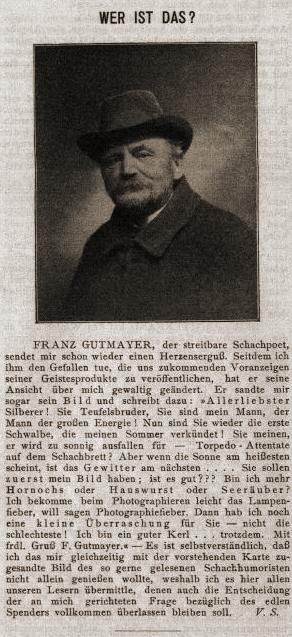

6623. Franz Gutmayer

A photograph of Franz Gutmayer from his book Turnierpraxis (Berlin and Leipzig, 1922):

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) sends this item from the Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung of 6 May 1916 (page 310):

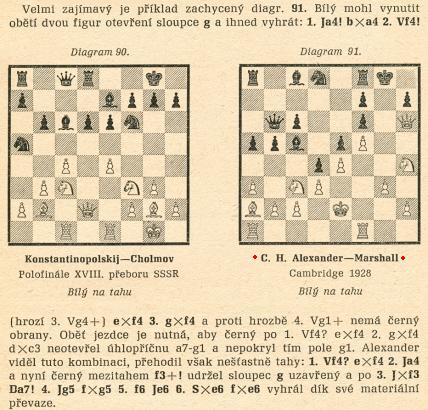

6624. Alexander v Marshall (C.N.s 3508 & 5262)

Information is still sought about the position discussed in C.N. 3508 and, in particular, about the identity of the players.

It was also published (with the specification C.H. Alexander) on page 47 of volume one of Taktika Moderního Šachu by L. Pachman (Prague, 1962):

The position was not included in the English version, Modern Chess Tactics (London, 1970).

6625. Language

On page 4 of the January 1981 BCM G.H. Diggle wrote:

‘Staunton, though he had his faults, would have cut his throat before penning the hideous expression “grandmaster norm”. He would have seen at once that the second word reduced the glory of the first to a meaningless nothing.’

That comment was the starting-point of a series of C.N. items on Chess and the English Language.

6626. ‘Grandmaster norm’

‘Suetin missed the grandmaster norm by ½ point.’

That was written by P.H. Clarke on page 148 of the May 1964 BCM, in a report on the USSR Zonal Tournament, but how much further back can the term ‘grandmaster norm’ be traced?

The succession of rule-changes for the awarding of international titles in the 1950s and 60s was outlined on pages 211-214 of Official Chess Handbook by K. Harkness (New York, 1967). Do readers know of a more detailed historical account, with specific reference to norms?

6627. San Remo, 1911

Pierre Bourget (Quebec, Canada) asks:

‘Do you have information on a ladies’ tournament held in San Remo, 1911 and won by Miss Finn?’

Information is sparse, but from brief reports in half-a-dozen European magazines of the time we have put together the final result:

1. Miss Kate Belinda Finn (London) 7 points (1,000 francs);

2. Miss Selma Cotton (London) 6 points (600 francs);

3. Mrs J.D. Rentoul (London) 5 points (400 francs);

4. Miss A. Smith-Cunninghame or Smith-Cuninghame (Edinburgh);

5. Mrs Charlotte Tiedge (Copenhagen);

6. Mrs Pillans J. Stevenson (London);

7. Countess Marie or Maria Fossati or Fossate (Turin);

8. Countess d’Arlay or d’Arley or Darlais (Paris).

Two other contestants, Mrs and Miss L. Sparlinger or Spalinger (Zurich), appear not to have completed the tournament. The event, organized by Theodor von Scheve, began on 6 March 1911. We have found no crosstable or games.

This photograph of Miss Finn (1870-1932) was published on page 70 of Chess Pie, 1922:

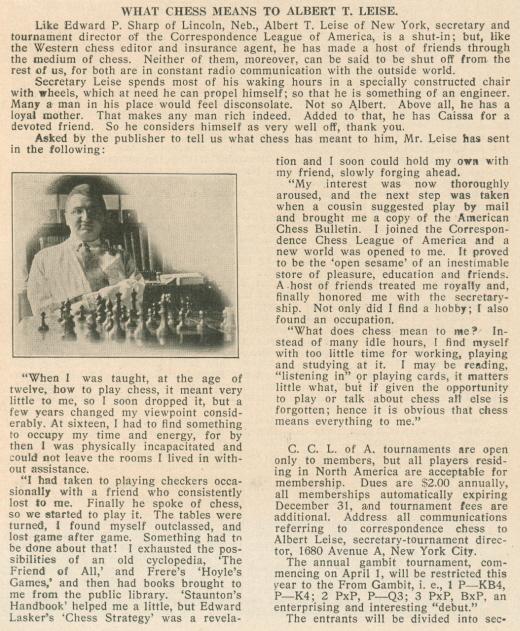

6628. Albert T. Leise (C.N. 6561)

C.N. 6561 discussed A.T. Leise, who played by telephone in a simultaneous display given by Capablanca.

From page 66 of the March 1924 American Chess Bulletin:

6629. Rudolf Swiderski’s suicide

Having followed up on a clue provided by Jon D’Souza-Eva (Oxford, England) about publication of news of Swiderski’s suicide in the Scottish press, we can quote a report on page 8 of The Scotsman, 12 August 1909:

‘Chess Champion’s Tragic End

Berlin, 11 AugustA telegram from Leipzig reports the suicide of Swiderski, the champion chess player of the world, under dramatic circumstances. The evidence points to Swiderski having taken his life on the 2d inst., but the body was only found today, being in a terrible state of decomposition. The unhappy man had apparently taken poison, and then shot himself with a revolver. Allegations of perjury in connection with a love affair had been made against the deceased, and it is supposed that fear of legal proceedings was the motive which led to the tragedy. – Central News.’

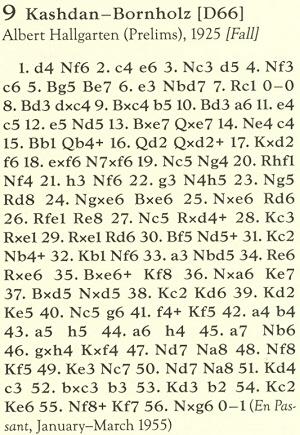

6630. Kashdan book (C.N. 6339)

Marc Hébert (Charny, Canada) expresses great disappointment with Isaac Kashdan, American Chess Grandmaster by Peter P. Lahde (Jefferson, 2009). He notes, by way of example, that the 1931 Olympiad in Prague is said to have taken place in June (pages 125-129), July (page 316) and August (page 12). Another curiosity is this pair of games, from pages 77 and 79:

Before agreeing to publish such a work by Mr Lahde, McFarland & Company, Inc. might usefully have looked at his book on Alekhine’s games.

6631. Pairing system (C.N. 6608)

In C.N. 6608 a reader asked about tournaments which used a pairing system similar to that of New York, 1924.

Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA) quotes from the Hastings, 1895 tournament book edited by Horace F. Cheshire (London, 1896):

‘The order of play and pairing will be decided by the president drawing lots publicly immediately before the commencement of the Tournament. The future pairing will depend on this, but will not be known until the morning of each day. (Page 6.)

‘The president then made the draw of the names to match with the numbers with which the pairings had been arranged; ... this draw determined the first moves and the pairings of all the rounds, but not the order in which the rounds were to be played. The draw was then made for the round for the day, and the president explained that he, or in his absence the director in charge, would make this draw each day before play commenced.’ (Pages 10-11, in the section entitled ‘The Opening Day’.)

‘No-one knew, till the morning of each day, who would meet ...’ (Page 367, under ‘The Innovations’.)

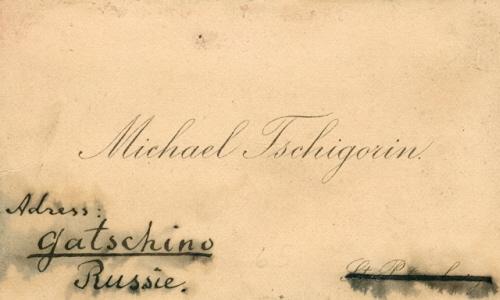

6632. Chigorin

Mr Wrinn also notes this photograph and signature opposite page 121 of the Hastings, 1895 tournament book and points out a comment on page 346:

‘We have spelt this expert’s name as he spells it himself when using English characters.’

That gave ‘Tchigorin’, although we note the following on page 39 of the February 1908 Wiener Schachzeitung:

From our collection we reproduce a visiting card (with smudged handwriting in ink):

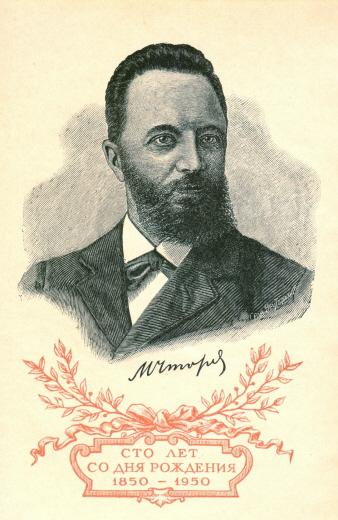

As regards Chigorin’s signature in Russian, below is the frontispiece of N.I. Grekov’s 1952 monograph on him (Moscow, 1952):

6633. Reinfeld and Rubinstein (C.N. 6518)

A further recollection by Reinfeld, from page 94 of his book Great Moments in Chess (New York, 1963):

‘Many years ago I played against Rubinstein in a simultaneous exhibition. I was almost cross-eyed with reverence for the great man, and, in Frank Marshall’s classic phrase, “he beat me like a child”. One detail still lingers in memory. Though Rubinstein was a stocky man with stubby fingers, his hands maneuvered the chessmen with such elegance that I was spellbound.’

6634. Morphy v Harrwitz (C.N. 6593)

The missed mate in two was discussed on pages 196-197 of a book by W. Ritson Morry and W. Melville Mitchell, who unpersuasively concluded:

‘How could two such writers [Max Lange and Howard Staunton] miss the simple mate? One can only suppose the players themselves indicated the line after the game and nobody bothered to check.’

The book appeared in the 1960s and 1970s under a slew of titles: Chess: A Way to Learn; Chess The Elements and the Play; Tackle Chess This Way; Tackle Chess; Chess Theory and Practice.

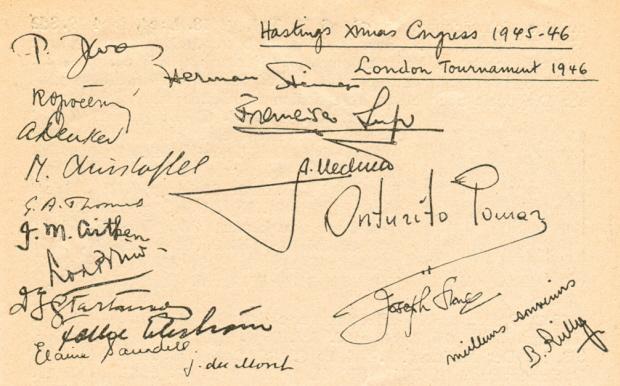

6635. Signatures

Source: Schweizerische Schachzeitung, March 1946, page 37.

6636. About 40%

The chapter regarding masters’ mistakes on pages 313-333 of The Personality of Chess by I.A. Horowitz and P.L. Rothenberg (New York, 1963) has 41 positions. About 40% of them are in The 10 Most Common Chess Mistakes by L. Evans (New York, 1998).

6637. Academic Dictionary of Games

The back cover of Academic Dictionary of Games edited by Shamshad Ahmed (Delhi, 2005) is full of Eastern promise:

‘The present publication is an up-to-date, authentic and comprehensive dictionary of games ... It aims to provide clear, concise, and correct definitions and descriptions of the terms used in games. ... This work is designed to be a comprehensive reference tool for games professionals, students and laymen interested in games. It is earnestly hoped that it will be an authoritative source to which one can turn with confidence for meaning and knowledge of the common, specialised and latest terms in games and allied fields.’

The Editor’s qualifications for the assignment are then commended:

‘Shamshad Ahmed, a renowned freelance journalist did his postgraduate diploma in journalism and mass communication in 1975. His area of specialisation is sports journalism.’

The 317-page dictionary includes dozens of chess definitions, but there is a difference. Whereas the entries for terms relating to other activities are serious/technical, the chess material is light-hearted. A sample page illustrates this:

Why should that be? Why should such a book have (on

page 151) ‘Naidni sgnik’ as the definition/description

of ‘King’s Indian reversed’? Was Mr Ahmed aware of

anything he was writing? Indeed, was he writing

anything?

In reality, all the chess-related entries have been copied, without credit, from a list presented by Eliot Hearst (compiled from readers’ contributions) in an article entitled ‘Chess Kaleidoscope’ on pages 224-225 of the October 1962 Chess Life. Making it even easier for Mr Ahmed to produce his ‘comprehensive reference tool’, the complete list is available on-line (credited to Professor Hearst) at a number of chess webpages, one example being an Addendum in The Campbell Report.

6638. Grandmaster draw (C.N. 3803)

We have found some occurrences of ‘grandmaster draw’ from 1948 (i.e. a couple of years before FIDE officially brought in the title ‘grandmaster’).

In a report on the world championship match-tournament page 11 of the May 1948 Chess Review had two instances:

‘Round eight produced the first “grandmaster draw” of the tourney. On the 24th move, Keres proposed a draw and Reshevsky accepted.’

‘Many people feel that the “grandmaster draw” is the bane of competitive play.’

From page 308 of the September 1948 BCM (a report by H. Golombek on the Stockholm Interzonal tournament):

‘The Lilienthal-Bronstein game was a typical example of the so-called “grandmaster” draw.’

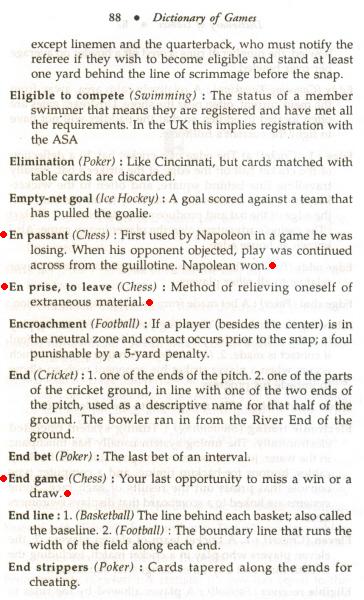

6639. Problem prodigy

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) sends this problem by Hyman Helfman of New Brunswick, NJ:

Source: Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 10 February 1921, page 3.

Helfman has a brief entry (with the spelling Helfmann) in Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia, the only information being that he was born in 1907. The records available from the familysearch.org website indicate that his date of birth was 7 April 1907 and that he died in June 1975.

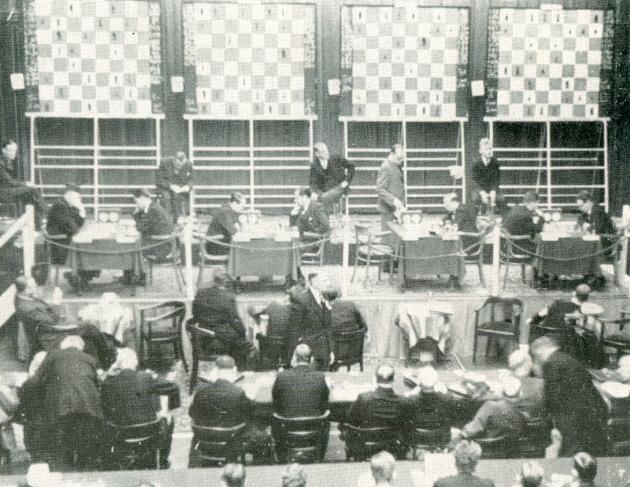

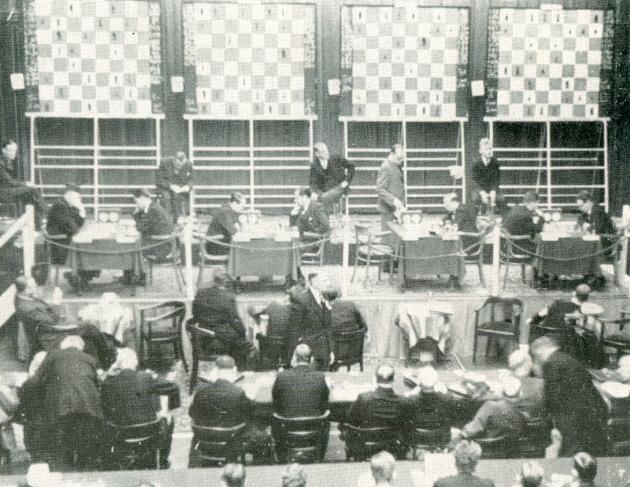

6640. Quiz question (C.N. 6621)

A number of readers gave the correct date: 6 November 1938.

The photograph was taken in Amsterdam during the first round of the AVRO tournament, the players being, from left to right, Euwe, Keres, Flohr, Capablanca, Alekhine, Reshevsky, Fine and Botvinnik. It was one of many shots from De Telegraaf reproduced on pages 139-142 of CHESS, 14 December 1938.

6641. Schlechter games (C.N. 6575)

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) notes that the Schlechter v Mieses game was given in an article about Schlechter by Ernst Grünfeld on pages 65-67 of the March 1931 Wiener Schachzeitung.

6642. Capablanca bibliography

José Raúl Capablanca by I. and V. Linder (Milford, 2010) stands out on one account only: its bibliography may be the most error-ridden ever published in a chess book. Although only four pages long, it features dozens of typos and other mistakes (with a far higher total if foreign accents are considered too). For an example we go no further than the first entry (on page 268):

No edition of Chess Fundamentals has contained an After ward (or Afterword) by Cherner (or Chernev). The book in question was My Chess Career.

6643. Thematic displays (C.N. 5314)

In C.N. 5314 Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) asked about simultaneous exhibitions in which all the games began with a thematic position.

He now points out a footnote on page 140 of Marshall-Angriff by N. Krogius and A. Mazukewitsch (East Berlin, 1989):

‘Diese und andere Partien mit Beteiligung von Mazukewitsch stammen aus einer Fernschach-Simultanvorstellung an 100 Brettern, die 1983 für Meisteranwärter und Spieler der Leistungsklasse 1 veranstaltet wurde.’ [‘This game and others involving Matsukevich were played in a 100-board simultaneous exhibition by correspondence organized in 1983 for candidate masters and category one players.’]

6644. Weiss v Blackburne

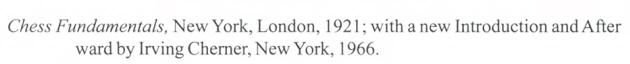

This position occurred after 41...Kd5 in Weiss v Blackburne, New York, 1889. Paul Gottlieb (East Brunswick, NJ, USA) notes that whereas databases state that the game continued 42 Bf2 f5 43 Kc3 g5, a sequence leading to a different position was given by Irving Chernev on page 144 of The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played (New York, 1965):

We have found no corroboration of the Chernev version, whereas 42 Bf2 f5 43 Kc3 g5 was the continuation given on page 5 of the New York Times of 27 April 1889 (the day after the game was played), page 145 of the May 1889 International Chess Magazine, page 75 of the tournament book by Steinitz, and page 127 of P. Anderson Graham’s book on Blackburne.

Chernev was, of course, aware of Steinitz’s annotations (at move 56 he quoted one of the world champion’s comments), so why did he give different play at moves 42 and 43?

6645. Mason problem

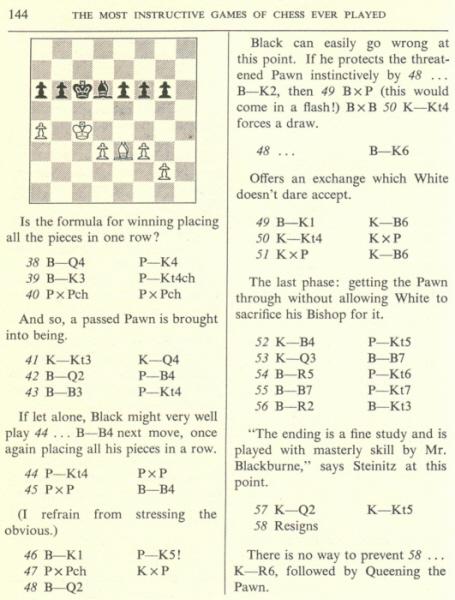

From page 172 of the 9 May 1889 Columbia Chess Chronicle:

The key given on page 218 of the 27 June 1889 issue was 1 Qh3, but there is also 1 Qf4+.

6646. Edward Mason

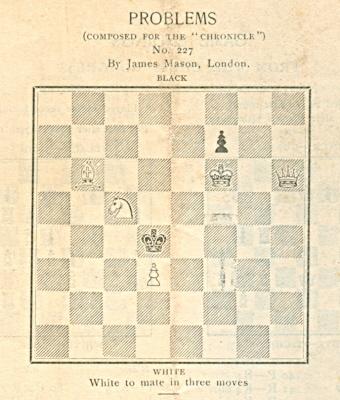

Wanted: information about a game discussed on page 113 of Adventure in Chess by Assiac (London, 1951):

Page 261 of the August 1948 BCM referred to

E. Mason as a British Chess Federation organizer, but

what more is known about him? (See also C.N. 4183.)

6647. World championship rules

W. Steinitz

Graeme Cree (Austin, TX, USA) asks about various aspects of the world championship rules for matches involving Steinitz.

There are complications aplenty, but in an attempt to set out the basic facts we have put together a feature article World Chess Championship Rules.

6648. Pure mates

Pete Tamburro (Morristown, NJ, USA) seeks examples of the pure mate (also known as the clean mate) in over-the-board play.

A specimen commonly given in chess books is Steinkühler v Blackburne, Manchester, 1863. See, for instance, page 306 of Irving Chernev’s 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955) and page 145 of Mr Blackburne’s Games at Chess by P. Anderson Graham (London, 1899). The latter book has the following note after 22...Bh3 mate:

‘In chess language this is a “clean” mate and is considered one of the most beautiful ever produced in actual play.’

See also C.N.s 4175 and 4188. For a less familiar game we now turn to page 214 of Schachgesellschaft Zürich 1809 bis 2009 by R. Forster (Zurich, 2009):

Arnold Krebs – Theo GinsburgZurich tournament, 1942-43

Queen’s Pawn Counter-Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d5 3 d4 dxe4 4 Nxe5 Bd6 5 Bc4 Bxe5 6 Qh5 Qxd4 7 Qxf7+ Kd8 8 Qf8+ Kd7 9 Bxg8 g6 10 Bg5 Qxb2 11 Qf7+ Kc6 12 Qc4+ Kb6 13 Be3+ Ka5

14 Nd2 Qxa1+ 15 Ke2 b5 16 Nb3+ Ka6 17 Qa4+ bxa4 18 Bc4+ Kb7 19 Na5 mate.

6649. Stray J. (C.N.s 4916 & 5666)

Another occurrence of ‘Samuel J. Reshevsky’ is on page 136 of The Personality of Chess by I.A. Horowitz and P.L. Rothenberg (New York, 1963).

Samuel Reshevsky

6650. Anti-Staunton

The chapter on Morphy (pages 233-245) in the above-mentioned Horowitz/Rothenberg book has some particularly biting comments on Howard Staunton:

‘England can look back to a long honorable history of gentlemen with unflinching devotion to the principle of fair play. Definitely not to be counted among them is Howard Staunton who somehow – with no convincing record to substantiate it – gained for himself, in his own day, a name of eminence in the chess world.’

‘... one of the most tragic chapters of shame in the history of chess is Staunton’s gross, shabby, arrogant treatment of a highly sensitive young chess genius [Morphy] ...’

‘Staunton initiated his campaign of perfidy in his 24 December 1857 column in the London Illustrated News [sic] ...’

‘In the meantime, the Shakespearean scholar, the man of culture, Howard Staunton, carried on dilatory tactics with a firm resolve, born of a craven soul, never to face alone an inevitable drubbing at the hands of the young American genius.’

‘Surprisingly, the one person of standing who has come to Staunton’s defense is H.J.R. Murray, famed chess historian. In an article in Chess Magazine [sic – it was the BCM], December 1908, Murray justifies Staunton’s stand [regarding the non-match against Morphy] on the ground of his “arduous literary occupations”. It is to be hoped that Murray’s conclusions in his History of Chess are based on more firm ground than in his preposterous apologia in behalf of the unspeakable Howard Staunton.’

‘Yes, this delicate human being [Morphy] was mortally wounded, for in his own mind he had failed to accomplish his purpose, and he was not at all impressed with the overwhelming evidence that Staunton had run away, cravenly, in virtual disgrace.’

As regards the criticism of H.J.R. Murray, the specific term ‘arduous literary occupations’ does not appear in his BCM article. It was used, however, by P.W. Sergeant when referring to Murray’s article on page 18 of Morphy’s Games of Chess (London, 1916):

Whether Horowitz and Rothenberg had read Murray’s article is an open question.

It should hardly be necessary to add that quotation of such anti-Staunton material (see also Attacks on Howard Staunton) indicates nothing about our own views. The purpose is merely to make texts available for general consideration, and the same applies to the next item.

6651. Bump of reason

‘Lady chessplayers are not so numerous as those of the opposite sex, probably chiefly due to the bump of reason not being as fully developed.’

Source: article in the St Louis Globe-Democrat quoted on page 12 of the January 1917 American Chess Bulletin.

6652. Jacques Futrelle

The famous short story ‘The Thinking Machine’ by Jacques Futrelle (1875-1912) was mentioned by P.W. Sergeant in the first paragraph of his article on Deschapelles on pages 117-119 of the April 1916 BCM:

‘Some years ago the late Jacques Futrelle, who was one of the Titanic victims, wrote a book called The Thinking Machine on the Case, describing certain exploits of a “famous scientist” who out-Sherlocks Sherlock Holmes in the detection of mysteries. In one of the stories in the series we read how the Professor after one hour’s instruction in the game of chess, hitherto unknown to him, defeats the Emmanuel [sic] Lasker of his day, using his logical faculty to supply the place of experience in the game. Now Jacques Futrelle, it need hardly be said, was no chessplayer. But there was a chessplayer flourishing a century ago who apparently asked the world to believe about him the same marvel as Futrelle puts before us in the imaginary case of The Thinking Machine. And this player was no other than Deschapelles.’

A website dedicated to Futrelle has the full text of the short story, and below we reproduce from page 7 of his anthology The Professor on the Case (the title of the British edition of The Thinking Machine on the Case) a passage which has intrigued chess enthusiasts:

Alain C. White discussed Futrelle in his article ‘Chess in Detective Stories’ on pages 305-309 of the August 1911 BCM, and regarding the game which Professor Van Dusen (having only just been introduced to chess by Hillsbury) won against the champion Tschaikowsky, A.C. White wrote:

‘It must have been a remarkable game, though; and anyone who could reconstruct it from the graphic description would confer a lasting favour on lovers of “brilliants”.’

Decades later another eminent figure raised the reconstruction question. From page 205 of the June 1948 BCM:

It needs to be considered whether 14 Rd4+ could be a discovered check.

6653. Alexander v Marshall (C.N.s 3508, 5262 & 6624)

On pages 107-108 of Alfil malo by B. Ivkov (Barcelona, 2002) the date of the Alexander v Marshall position is given as 1938, not 1928. With regard to the quest for the full game-score, is that an error or a clue?

Certainly, prudence is required with the book, a Serbo-Croatian work translated into Spanish. Its overall unreliability may be gauged from some of the names featured: Edw. Asker, Dechapel (in a game against Labourdonet), Fisher (passim and, for instance, in the game D. Bern-Fisher), Korchno, Kreychik, Kreytschik, Mardhall, Nimzowits, Pilsburry, Schlehter, Semish, Shlechter (a game dated 1860), Smislosv, Spielman, Spilmann, Tall, Tarasch and Tarash.

6654. Dmitri Shostakovich

From pages 109-110 of Shostakovich A Life by Laurel E. Fay (Oxford, 2000):

‘Chess was chiefly a youthful infatuation; although he followed match play, he was never as serious a competitor as Prokofiev or David Oistrakh. In old age one of the favourite yarns he liked to retell was how, as a callow teenager, he had challenged and lost to Alexander Alekhine, something which could have taken place only before the future world champion left Russia for good in the spring of 1921.’

The source for this information is given on page 310:

‘M. Dolgopolov, “Budem znakomï – Alekhin ...”, Izvestiya, 17 August 1974, 5. Among others who recall hearing the composer recount versions of this story are Yevgeniy Dolmatovsky and Mstislav Rostropovich.’

A photograph of Shostakovich at the chessboard was given on page 354 of the November 1946 BCM:

| First column | << previous | Archives [71] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.